- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

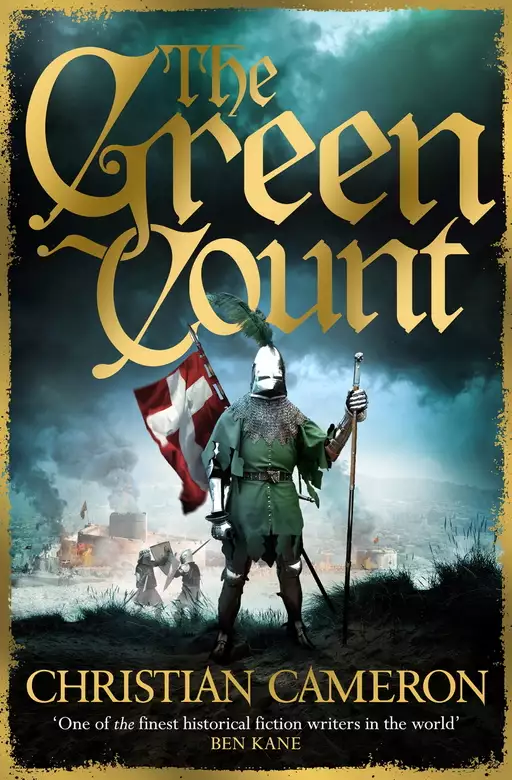

Synopsis

After the bloody trials of Alexandria, Sir William Gold is readying for a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He hopes, too, that the Holy City might allow his relationship with Emile, cousin of the Green Count of Savoy, to develop. But the Roman Emperor of Constantinople has been taken hostage by an unknown enemy, and the Green Count is vital to the rescue effort. It is up to Sir William to secure his support, but he soon finds that his past, and his relationship with Emile, might have repercussions he had not foreseen...Suddenly thrust onto the stage of international politics, Sir William finds himself tangled in a web of plots, intrigue and murder.

Release date: July 13, 2017

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Green Count

Christian Cameron

Arming sword – A single-handed sword, thirty inches or so long, with a simple cross guard and a heavy pommel, usually double-edged and pointed.

Arming coat – A doublet either stuffed, padded, or cut from multiple layers of linen or canvas to be worn under armour.

Alderman – One of the officers or magistrates of a town or commune.

Bailli – A French royal officer much like an English sheriff; or the commander of a ‘langue’ in the Knights of Saint John.

Basilard – A dagger with a hilt like a capital I, with a broad cross both under and over the hand. Possibly the predecessor of the rondel dagger, it was a sort of symbol of chivalric status in the late fourteenth century. Some of them look so much like Etruscan weapons of the bronze and early iron age that I wonder about influences . . .

Basinet – A form of helmet that evolved during the late middle ages, the basinet was a helmet that came down to the nape of the neck everywhere but over the face, which was left unprotected. It was almost always worn with an aventail made of maille, which fell from the helmet like a short cloak over the shoulders. By 1350, the basinet had begun to develop a moveable visor, although it was some time before the technology was perfected and made able to lock.

Brigands – A period term for foot soldiers that has made it into our lexicon as a form of bandit – brigands.

Burgher – A member of the town council, or sometimes, just a prosperous townsman.

Commune – In the period, powerful towns and cities were called communes and had the power of a great feudal lord over their own people, and over trade.

Coat-of-plates – In the period, the plate armour breast and back plate were just beginning to appear on European battlefields by the time of Poitiers – mostly due to advances in metallurgy which allowed larger chunks of steel to be produced in furnaces. Because large pieces of steel were comparatively rare at the beginning of William Gold’s career, most soldiers wore a coat of small plates – varying from a breastplate made of six or seven carefully formed plates, to a jacket made up of hundeds of very small plates riveted to a leather or linen canvas backing. The protection offered was superb, but the garment is heavy and the junctions of the plates were not resistant to a strong thrust, which had a major impact on the sword styles of the day.

Cote – In the novel, I use the period term cote to describe what might then have been called a gown – a man’s over-garment worn atop shirt and doublet or pourpoint or jupon, sometimes furred, fitting tightly across the shoulders and then dropping away like a large bell. They could go all the way to the floor with buttons all the way, or only to the middle of the thigh. They were sometimes worn with fur, and were warm and practical.

Demesne – The central holdings of a lord – his actual lands, as opposed to lands to which he may have political rights but not taxation rights or where he does not control the peasantry.

Donjon – The word from which we get dungeon.

Doublet – A small garment worn over the shirt, very much like a modern vest, that held up the hose and sometimes to which armour was attached. Almost every man would have one. Name comes from the requirement of the Paris Tailor’s guild that the doublet be made – at the very least – of a piece of linen doubled – thus, heavy enough to hold the grommets and thus to hold the strain of the laced-on hose.

Gauntlets – Covering for the hands was essential for combat. Men wore maille or scale gauntlets or even very heavy leather gloves, but by William Gold’s time, the richest men wore articulated steel gauntlets with fingers.

Gown – An over-garment worn in Northern Europe (at least) over the kirtle, it might have dagged or magnificently pointed sleeves and a very high collar and could be worn belted, or open to daringly reveal the kirtle, or simply, to be warm. Sometimes lined in fur, often made of wool.

Haubergeon – Derived from hauberk, the haubergeon is a small, comparatively light maille shirt. It does not go down past the thighs, nor does it usually have long sleeves, and may sometimes have had leather reinforcement at the hems.

Helm or haum – The great helm had become smaller and slimmer since the thirteenth century, but continued to be very popular, especially in Italy, where a full helm that covered the face and head was part of most harnesses until the armet took over in the early fifteenth century. Edward III and the Black Prince both seem to have worn helms. Late in the period, helms began to have moveable visors like basinets.

Hobilar – A non-knightly man-at-arms in England.

Horses – Horses were a mainstay of medieval society, and they were expensive, even the worst of them. A good horse cost many days’ wages for a poor man; a warhorse cost almost a year’s income for a knight, and the loss of a warhorse was so serious that most mercenary companies specified in their contracts (or condottas) that the employer would replace the horse. A second level of horse was the lady’s palfrey – often smaller and finer, but the medieval warhorse was not a giant farm horse, but a solid beast like a modern Hanoverian. Also, ronceys which are generally inferior smaller horses ridden by archers.

Hours – The medieval day was divided – at least in most parts of Europe – by the canonical periods observed in churches and religious houses. The day started with matins very early, past nonnes in the middle of the day, and came around to vespers towards evening. This is a vast simplification, but I have tried to keep to the flavor of medieval time by avoiding minutes and seconds.

Jupon – A close fitting garment, in this period often laced, and sometimes used to support other garments. As far as I can tell, the term is almost interchangeable with doublet and with pourpoint. As fashion moved from loose garments based on simply cut squares and rectangles to the skintight, fitted clothes of the mid-to-late fourteenth century, it became necessary for men to lace their hose (stockings) to their upper garment – to hold them up! The simplest doublet (the term comes from the guild requirement that they be made of two thicknesses of linen or more, thus ‘doubled’) was a skintight vest worn over a shirt, with lacing holes for ‘points’ that tied up the hose. The pourpoint (literally, For Points) started as the same garment. The pourpoint became quite elaborate, as you can see by looking at the original that belonged to Charles of Blois online. A jupon could also be worn as a padded garment to support armour (still with lacing holes, to which armour attach) or even over armour, as a tight-fitting garment over the breastplate or coat-of-plates, sometimes bearing the owner’s arms.

Kirtle – A women’s equivalent of the doublet or pourpoint. In Italy, young women might wear one daringly as an outer garment. It is skintight from neck to hips, and then falls into a skirt. Fancy ones were buttoned or laced from the navel. Moralists decried them.

Langue – One of the sub-organizations of the Order of the Knights of Saint John, commonly called the Hospitallers. The langues did not always make sense, as they crossed the growing national bounds of Europe, so that, for example, Scots knights were in the English Langue, Catalans in the Spanish Langue. But it allowed men to eat and drink with others who spoke the same tongue, or nearer to it. To the best of my understanding, however, every man, however lowly, and every serving man and woman, had to know Latin, which seems to have been the order’s lingua franca. That’s more a guess than something I know.

Leman – A lover.

Longsword – One of the period’s most important military innovations, a double-edged sword almost forty-five inches long, with a sharp, armour-piercing point and a simple cross guard and heavy pommel. The cross guard and pommel could be swung like an axe, holding the blade – some men only sharpened the last foot or so for cutting. But the main use was the point of the weapon, which, with skill, could puncture maille or even coats-of-plates.

Maille – I use the somewhat period term maille to avoid confusion. I mean what most people call chain mail or ring mail. The manufacturing process was very labour intensive, as real mail has to have each link either welded closed or riveted. A fully armoured man-at-arms would have a haubergeon and aventail of maille. Riveted maille was almost proof against the cutting power of most weapons – although concussive damage could still occur! And even the most strongly made maille is ineffective against powerful archery, spears, or well-thrust swords in the period.

Malle – Easy to confuse with maille, malle is a word found in Chaucer and other sources for a leather bag worn across the back of a horse’s saddle – possibly like a round-ended portmanteau, as we see these for hundreds of years in English art. Any person travelling, be he or she pilgrim or soldier or monk, needed a way to carry clothing and other necessities. Like a piece of luggage, for horse travel.

Partisan – A spear or light glaive, for thrusting but with the ability to cut. My favorite, and Fiore’s, was one with heavy side-lugs like spikes, called in Italian a ghiavarina. There’s quite a pretty video on YouTube of me demonstrating this weapon . . .

Pater Noster – A set of beads, often with a tassle at one end and a cross at the other – much like a modern rosary, but straight rather than in a circle.

Pauldron or Spaulder – Shoulder armour.

Prickers – Outriders and scouts.

Rondel Dagger – A dagger designed with flat round plates of iron or brass (rondels) as the guard and the pommel, so that, when used by a man wearing a gauntlet, the rondels close the space around the fingers and make the hand invulnerable. By the late fourteenth century, it was not just a murderous weapon for prying a knight out of plate armour, it was a status symbol – perhaps because it is such a very useless knife for anything like cutting string or eating . . .

Sabatons – The ‘steel shoes’ worn by a man-at-arms in full harness, or full armour. They were articulated, something like a lobster tail, and allow a full range of foot movement. They are also very light, as no fighter would expect a heavy, aimed blow at his feet. They also helped a knight avoid foot injury in a close press of mounted mêlée – merely from other horses and other mounted men crushing against him.

Sele – Happiness or fortune. The sele of the day is the saint’s blessing.

Shift – A woman’s innermost layer, like a tight-fitting linen shirt at least down to the knees, worn under the kirtle. Women had support garments, like bras, as well.

Tow – The second stage of turning flax into linen, tow is a fibrous, dry mass that can be used in most of the ways we now use paper towels, rags – and toilet paper. Biodegradable, as well.

Yeoman – A prosperous countryman. Yeoman families had the wealth to make their sons knights or squires in some cases, but most yeoman’s sons served as archers, and their prosperity and leisure time to practise gave rise to the dreaded English archery. Only a modestly well-to-do family could afford a six foot yew bow, forty or so cloth yard shafts with steel heads, as well as a haubergeon, a sword, and helmet and perhaps even a couple of horses – all required for military service.

Prologue

Calais, June 1381

Chaucer smiled. ‘You are quite the hidden man, William. I had no idea you held a barony on Cyprus.’ He raised his cup to Gold. ‘That was a fine tale. I think I even believe parts of it. Did you go to Jerusalem?’

Gold nodded. ‘We did. But you know Sabraham, so you’ve heard all this before,’ he said.

Chaucer laughed. ‘I don’t need your word on it to know that a crusade manned with the same mercenaries who burned France would come to a bad end,’ he said. He set his wine cup down with a click. ‘But you haven’t made it to the Green Count’s crusade or the Italian Wedding yet, much less to being the Captain of Venice.’

‘By God’s grace, Master Chaucer! Why not regale us with your own Spanish war? You spin words at least as well as Messire Froissart. And you were, I think, with the prince in Spain?’

Chaucer nodded. ‘Aye, William. We know all of each other’s secrets.’

Sir William laughed. ‘Not all, I think, Geoffrey.’

Froissart finished his wine. ‘I would very much like to hear of the tournament at Prince Lionel’s wedding – from a participant. But please tell me of Jerusalem!’

Sir William nodded. ‘Oh, the Italian Wedding … the lists there were murderous. And it was worse behind the tapestries.’ He laughed.

Froissart looked dismayed.

Chaucer guffawed. ‘Now there’s a tale!’

Morning came with the crowing of cocks and the rattle of dishes. The inn had remained busy until late, as a famous knight had told his tales of war in the Holy Land, and men had come: men from the castle, men from the garrison, men of the sword and men of the pen. Calais was a busy town, full of both soldiers and merchants, and a good tale was worth the cost of some beer.

But when morning came, there were hard heads and unfinished works, and crockery that had been left on the trestle tables being cleared away; bits of muttons stuck to the pewter, and the lees of wine dried like old blood in the cups. The inn’s servants, most of them young women, moved briskly, picking up dishes and dropping them into steaming coppers of sudsy water. The youngest girls swept the unwanted food into wooden buckets: bread trenchers full of meat juice, and small dishes of peas and turnip which had to be scraped with your fingers into the bucket and then stacked, because Mistress was this particular. And the buckets of food-slop went to the pigs. Nothing was wasted except the youths of a dozen young women.

William Gold sat in a corner and watched them while he tied his points. Some of them didn’t even know he was there; others avoided him the way mice move around a sleeping cat. The innkeeper’s daughter brought him a cup of small beer and he raised it to her, silently, and went back to his points.

The next time the knight looked up, his former companion Chaucer was seated at his table.

‘By the Trinity, messire, you move too silently for an honest man,’ Gold said.

Chaucer wrinkled his lip and sat heavily. ‘I’m not sure I’ve ever claimed to be an honest man,’ the courtier replied. ‘Have we received passports? And what on earth are you doing awake at this ungodly hour? We were only just abed!’

Gold leaned back and drank off his small beer. ‘You are awake yourself,’ he said. ‘Nothing from the castle. Nor will there be. It’s Sunday, messire. We should all be on our knees to our saviour.’

Chaucer winced. ‘You do not mean to spend the whole of the day on your knees,’ he said.

Gold shook his head. ‘I have a great deal for which to be thankful,’ he said. His eyes happened to cross with Aemilie’s, the innkeeper’s daughter. She flushed.

Chaucer shook his head and snarled, ‘You pious hypocrite!’

Gold looked at him as if he smelled something foul. ‘Whatever prompted that, messire, it was ill said.’

Chaucer looked meaningfully at the young woman.

Gold raised an eyebrow. ‘Honi soit qui mal y pense,’ he said. ‘I am off to Mass. Aemilie, would you run an errand for my old legs?’

‘Old?’ Chaucer asked. ‘Have you crossed forty yet?’

‘Yes, My Lord,’ she said with a curtsy. In fact, most of her attention was on a younger woman working a stain in one of the oak tables.

‘My book of hours is on my bed,’ Gold said.

Aemilie bobbed again and vanished towards the stairs.

‘Do you really imagine I’m tupping servant girls?’ Gold growled.

‘You certainly have in the past,’ Chaucer replied.

‘On Sunday?’ Gold asked.

‘Are you really so naive as to imagine that God, if there is a god, counts the days?’ Chaucer asked.

Gold stood with his hands on his hips, his right hand very close to his dagger hilt. Chaucer sat at the table, apparently unmoved by the threat of the big, red-headed knight.

Slowly, Gold’s body relaxed. ‘By the saviour,’ he said, ‘I forget how you are, Geoffrey.’

Chaucer managed a slow smile. ‘I forget how easy you are to sting.’

Aemilie appeared, bounced down the stairs, and handed over the knight’s book of hours. It was very plain: a simple red leather cover, a few vellum pages with a pretty little painting of the Annunciation of the Virgin, and the rest paper; plain as plain, it might have belonged to any housewife in Calais. The cover had shield-shaped rivets bearing Gold’s arms and a clasp.

Chaucer took the book of hours, opened the latch, and flipped through it.

‘By the rood,’ he said with a smile. ‘You copied it yourself.’

‘So I did,’ Gold admitted. ‘My clerking is not so bad.’

‘All your letters lean like drunken men,’ Chaucer announced.

Gold, stung, drew himself up. ‘I do not make letters for my living,’ he said.

Chaucer smiled. ‘And I do – no doubt there is something witty to be said about the pen being mightier. Let us, for all love, go off to Mass instead.’

Aemilie’s father came out to see his two famous guests out of the courtyard, and then he came back in, the smile wiped off his face, to glare at his daughter.

‘Do not flirt with Sir William,’ he said. ‘Men like Sir William are … very dangerous. And not suitable … company.’

Aemilie put her shoulders back and turned her head slightly away. ‘I can handle myself, mon pere. And he is a true knight —’

‘A true knight who has sent more souls to Satan than the Plague,’ her father said, and then ruffled her hair. ‘I’m sorry. I was rankled by Master Chaucer’s … words.’

Aemilie nodded. ‘Why are they so friendly to each other? If they hate each other?’

Her father smoothed his houpland and pulled the liripipe on his hood carefully through the belt that held his purse. ‘I don’t think they hate each other,’ he said carefully.

‘Master Chaucer speaks to injure Sir William,’ Aemilie said.

‘Hmm,’ her father said. ‘Yes. But perhaps … Sweeting, men are odd cattle, and these two have seen many things together. I think that they …’ He paused, looking into the kitchen, Whatever fatherly wisdom he was going to impart was lost in a crash of crockery and the sound of pewter flagons bouncing off stone and tile, and enough blasphemy to fill the circles of Hell so lovingly described by Chaucer’s hero, Dante.

Three hours later, Sir William returned, accompanied not just by Chaucer but by his own squire and a dozen of his pages and men-at-arms and archers as well. If they were all nursing the results of the night before, none of them showed any sign. Aemilie directed her dozen women in serving wine and loaves of good bread and wedges of thick English cheese. Men who’d been to Mass had not eaten.

Sir William met her eyes. ‘And you, mam’selle?’ he asked. ‘When do you go to Mass?’

‘Which I’ve been,’ she said with a curtsy.

Chaucer nodded. ‘She’s been up an hour before we were, William. Probably heard Matins.’

‘And I say my own hours,’ she put in. And then curtsied, as she had spoken out of turn, but she was not willing that Master Chaucer would believe her a light of love.

Chaucer smiled at her. ‘You have a book of hours, lass?’ he asked.

She went behind the inn’s low bar and emerged with her book, which was long and narrow and conscientiously made. It had more decorations than Gold’s.

‘Flemish?’ Chaucer asked.

Aemilie nodded. ‘My pater brought it to me. For Christmas,’ she said.

Chaucer nodded. ‘Would you like a new prayer, Aemilie?’ he asked.

‘Oh,’ she said. ‘Are you a priest?’ She didn’t think he looked like a priest, but a woman could never tell.

‘Just a clerk, lady. But I write prayers. Here – how do you feel about Saint Mary Magdalene?’ he asked.

Aemilie frowned. ‘I wonder …’

Chaucer’s eyes sparkled with his particular and wicked merriment. He took a pen case off his hip and paused. ‘Perhaps not the right saint for an attractive young woman. Saint Catherine of Alexandria?’

‘The Blessed Virgin, if you please,’ she said, bobbing.

Chaucer flipped through her book. He paused, took out his own, the most elaborate of the three on the table, and opened it to a pretty picture of the Annunciation.

‘Damn me, that is fine,’ Gold said.

‘You know where I got this,’ Chaucer said. He looked up from his pens.

‘By the sweet Saviour of man,’ Gold said. He weighed it in his hand as if it was made of gold and he found it wanting. ‘Hers?’ he asked, and his tone invested hers with a great deal of meaning.

‘Oh, yes,’ Chaucer said.

He began to copy his prayer to the Virgin into the young woman’s book. His script was perfect: neat and fine and dark.

Even the innkeeper stopped to watch him write.

‘Beautiful,’ he said.

Chaucer smiled. He was concentrating; his mouth was slightly open, and Gold smiled to see it.

Chaucer came to the mid-point in the prayer and breathed before writing domini.

‘Will you tell Froissart about Jerusalem?’ he asked.

‘Of course. It’s wet outside – the lads like a story and so do the lasses.’ Gold looked out of the narrow windows and shrugged. ‘Will you tell them about the Italian Wedding?’

Chaucer frowned. ‘No. You may, if you like. I …’ He took a breath and finished the prayer. ‘I still see it.’

Gold knew that Chaucer meant ‘I still see her. Dead.’

He reached out and put a hand on Chaucer’s shoulder.

An hour later, the common room was full again. Gold sat back to tell his tale. Froissart had a pen in his hand today, and so did Chaucer. But Chaucer was copying prayers for Aemilie, and filling her little book. Froissart was copying down what Sir William Gold had to say.

Famagusta

November 1365 – January 1366

There are many advantages to word fame, and not the least that men will more readily follow you if they’ve heard your name.

There were many men on Rhodes and Cyprus in the autumn of the year of our Lord 1365 who knew my name. I was not famous, but I had been knighted by an imperial knight on a famous field of battle and now I had played a small role in a crusade.

So when I made it known that my friends and I planned to take an armed party to Jerusalem, there was no lack of volunteers.

If you’ve been listening, you have heard all that I have to say about Alexandria. What happened there is still black to me, and just telling it seems like a lash upon my soul. I won’t tell it again. But I will say that as the gentle weather of that autumn kissed the streets of Rhodes, many men had time to repent the sins they’d committed in the streets of Alexandria, and to think that they’d best spend some of the loot they’d gained by visiting the holiest city in the world, the scene of Christ’s passion, the centre of the middlerealm, as the old monks would have it.

Many of the routiers left for Italy as soon as the Venetians and the Genoese turned their ships for home, but many stayed, because the king of Cyprus said, or at least he said at first, that he would launch a second attack immediately. But from Rhodes, the capital of my Order and Christendom’s greatest fortress, we heard that the king had sunk into a lethargy. He had reason: his people were restless, he’d mortgaged his kingdom’s future on his crusade, and his wife, so men said, had been both unfaithful in body and unfaithful as a vassal, stirring treason. Although I was now a baron of Cyprus, I was not tempted to remain and be a courtier at that court.

Not even a little.

Besides, my friends – my surviving friends, Fiore dei Liberi, a knight of Udine, and Nerio Acciaioli, a Florentine knight, and Miles Stapleton, who was knighted on the beach of Alexandria with Steven Scrope – you know that name, don’t you, Chaucer? Of course you do … At any rate, my friends had sworn on our brother Juan’s tomb to go to Jerusalem. And I had promised my lady, Emile d’Herblay.

We had originally thought that it would just be a few of us. In fact, when we first broached the idea on Rhodes, the older Hospitallers told us to go unarmed, as pilgrims. The Hospital is, in part, a business, and maintains hospices, inns, and hospitals across Europe for pilgrims going to any of the great sites: Padua, Rome, Compostela, Constantinople or Athens or Corinth or Jerusalem, holy of holies. In Outremer, they arrange letters of credit and travel passes with the local Islamic rulers. And let me just add, as a man of the world, that it was said on Rhodes by the oldest knights that the Holy Land was safer and easier for pilgrims under the Mamluks than it had ever been under Frankish rule.

I suspect I’ll have a great deal to say tonight about the Mamluks and the Turks and their ways. I’ll let that be, for now.

So we laid our plans, and then, perhaps a month after Alexandria and less than a week before we were due to board a Venetian great galley for the short dash to Jaffa, Nicholas Sabraham appeared as if out of the aether, as he usually did, and we sat in the courtyard of the English inn. The sunlight of the Mediterranean is still brilliant in October, and there were old sails from the Order’s fighting galleys rigged in most courtyards so that tired old soldiers could sit and tell lies in comfort.

By the Cross, friends, I thought I was old that autumn. Old, wise, and tired.

Sabraham was a favourite with my archer, John the Turk. They swapped some greeting in Turkish, and John fetched Sabraham a cup of wine, which he seldom did for me. John was a warrior and not a servant. As I have mentioned before, he would clean armour all day and his care of horses was divinely inspired, but laying out clothes and serving wine was generally beneath him. I should add for those new to the story that John was not a Turk at all, but a Kipchak, and he’d been sold as a Mamluk, taken by the Turks, forced to convert to Islam, and then taken by me and forced to convert to Christianity. I’m also sad to say, even now, that he was a better Christian than I.

Except on the battlefield.

Sabraham was another odd one, an Englishman who was a veteran of the East. Some said his family were Jews; that’s possible, as the Hospitallers generally aided English Jews and still do. Sabraham spoke ten local languages and had lived in Aleppo, Damascus and Cairo and he knew more about the East than any Englishman I ever met, even in Venice. He generally led any exploratio of the infidels, and often went by himself. He was friends with Nerio’s uncle, the great knight Niccolò Acciaioli. Did I not say that I myself enjoyed some little word fame? Sabraham was widely regarded as one of the best knights, in council or in a fight, to adorn the Order in many years.

There he sat, in the bright sunlight of Outremer, dressed in a dreadful fustian arming coat that had been new when Caesar commanded armies in Gaul and padded arming hose so grimy with dirt and oil that they were somewhere between grey and black.

‘You are going to the Holy Land?’ he asked, when his wine was in his hand.

I waved vaguely at the Grand Master’s palace. ‘I have our passports,’ I said. ‘Quite a sheaf of letters and several pounds of seals.’

Sabraham drank wine. ‘Good for nothing but starting fires, unless they can be scraped clean,’ he said.

‘What?’ I sputtered, or something equally nice. I’d spent the better part of two weeks walking from one office to another, arranging for all the parchment to get us to Jerusalem.

Sabraham sat back and fingered his beard. A pair of squires came into the yard with swords, saw us, and went somewhere else. My young scapegrace, Marc-Antonio, appeared and poured wine and muttered apologies.

‘Oh, go and train, you worthless boy’ I snapped. He was late to rise because he was fornicating. I didn’t give a whit what he did in his late hours, but as I was chaste and he was not, I resented him. I didn’t know the girl, but barracks rumour had it that she was Genoese and pretty and well-born, which suggested that there might be trouble.

Sabraham raised his bushy eyebrows. ‘You are not usually so surly, Sir William,’ he said.

‘Your pardon, my friend,’ I muttered. I wanted to be going to Jerusalem for a wide variety of reasons, a few spiritual, and most of them petty and even venal. My lady would not hear of a wedding, or anything beyond a chaste kiss, until we had been to Jerusalem.

Given the passion of her welcome to me on my return from the crusade, I had expected more.

Ah, yes, the endless ability of men to layer sin on sin. Fornication, adultery, impiety …

I was distracted by my thoughts.

Sabraham cleared his throat so I started, and then nodded, as if accepting my apology. ‘I am sorry if I bear bad tidings, William,’ he said. ‘But Mamluk rule on the coasts of the Holy Land has collapsed. The sultan has recalled almost all of his soldiers. There is no military governor in Jerusalem, even if he would accept a letter from a hostile power, which we are, just now. Does the Grand Master think that we can sack Alexandria and then casually return to the status quo ante bellum?’ Sabraham finished his wine in two great gulps.

‘I am not alone in surliness, I find,’ I said, in a friendly voice. One does not want to be mistaken with a man as deadly as Sabraham.

He waved a hand in the air, dismis

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...