- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

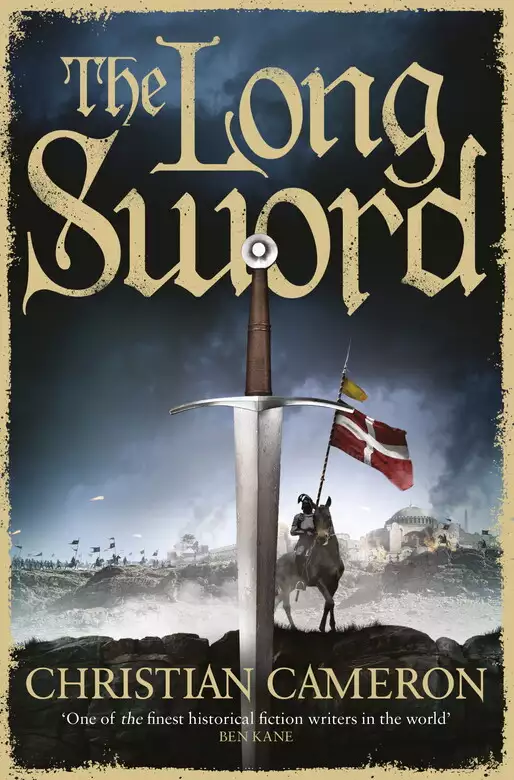

Pisa, May 1364. Sir William Gold is looking forward to a lucrative career as a hired sword in the endless warring between Italy's city states. But when a message comes from the Grand Master of the Hospitaliers, William is forced to leave his dreams of fame and fortune behind him. The Hospitaliers are gathering men for a crusade, and Sir William must join them. Yet before they set out for the holy land, the knights face deadly adversaries much closer to home . . .In the twisting politics of Italy, no one can be trusted. Can Sir William and his knights survive this impossible mission into the heart of the enemy?

Release date: November 20, 2014

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Long Sword

Christian Cameron

GLOSSARY

Arming sword – A single-handed sword, thirty inches or so long, with a simple cross guard and a heavy pommel, usually double edged and pointed.

Arming Coat – A doublet either stuffed, padded, or cut from multiple layers of linen or canvas to be worn under armour.

Alderman – One of the officers or magistrates of a town or commune.

Bailli – A French royal officer much like an English sheriff; or the commander of a ‘langue’ in the Knights of Saint John.

Basilard – A dagger with a hilt like a capital I, with a broad cross both under and over the hand. Possibly the predecessor of the rondel dagger, it was a sort of symbol of chivalric status in the late fourteenth century. Some of them look so much like Etruscan weapons of the bronze and early iron age that I wonder about influences . . .

Bassinet – A form of helmet that evolved during the late middle ages, the bassinet was a helmet that came down to the nape of the neck everywhere but over the face, which was left unprotected. It was almost always worn with an aventail made of maille which fell from the helmet like a short cloak over the shoulders. By 1350, the bassinet had begun to develop a moveable visor, although it was some time before the technology was perfected and made able to lock.

Brigans – A period term for foot soldiers that has made it into our lexicon as a form of bandit – brigands.

Burgher – A member of the town council, or sometimes, just a prosperous townsman.

Commune – In the period, powerful towns and cities were called communes and had the power of a great feudal lord – over their own people, and over trade.

Coat-of-plates – In period, the plate armour breast and back plate were just beginning to appear on European battlefields by the time of Poitiers – mostly due to advances in metallurgy which allowed larger chunks of steel to be produced in furnaces. Because large pieces of steel were comparatively rare at the beginning of William Gold’s career, most soldiers wore a coat of small plates – varying from a breastplate made of six or seven carefully formed plates, to a jacket made up of hundeds of very small plates riveted to a leather or linen canvas backing. The protection offered was superb, but the garment is heavy and the junctions of the plates were not resistant to a strong thrust, which had a major impact on the sword styles of the day.

Cote – In the novel, I use the period term cote to describe what might then have been called a gown – a man’s over-garment worn atop shirt and doublet or pourpoint or jupon, sometimes furred, fitting tightly across the shoulders and then dropping away like a large bell. They could go all the way to the floor with buttons all the way, or only to the middle of the thigh. They were sometimes worn with fur, and were warm and practical.

Demesne – The central holdings of a lord – his actual lands, as opposed to lands to which he may have political rights but not taxation rights or where he does not control the peasantry.

Donjon – The word from which we get dungeon.

Doublet – A small garment worn over the shirt, very much like a modern vest, that held up the hose and sometimes to which armour was attached. Almost every man would have one. Name comes from the requirement of the Paris Tailor’s guild that the doublet be made – at the very least – of a piece of linen doubled – thus, heavy enough to hold the grommets and thus to hold the strain of the laced-on hose.

Gauntlets – Covering for the hands was essential for combat. Men wore maille or scale gauntlets or even very heavy leather gloves, but by William Gold’s time, the richest men wore articulated steel gauntlets with fingers.

Gown – An over garment worn in Northern Europe (at least) over the kirtle, it might have dagged or magnificently pointed sleeves and a very high collar and could be worn belted, or open to daringly reveal the kirtle, or simply, to be warm. Sometimes lined in fur, often made of wool.

Haubergeon – Derived from hauberk, the haubergeon is a small, comparatively light maille shirt. It does not go down past the thighs, nor does it usually have long sleeves, and may sometimes have had leather reinforcement at the hems.

Helm or haum – The great helm had become smaller and slimmer since the thirteenth century, but continued to be very popular, especially in Italy, where a full helm that covered the face and head was part of most harnesses until the armet took over in the early fifteenth century. Edward III and the Black Prince both seem to have worn helms. Late in the period, helms began to have moveable visors like bassinets.

Hobilar – A non-knightly man-at-arms in England.

Horses – Horses were a mainstay of medieval society, and they were expensive, even the worst of them. A good horse cost many days’ wages for a poor man; a warhorse cost almost a year’s income for a knight, and the loss of a warhorse was so serious that most mercenary companies specified in their contracts (or condottas) that the employer would replace the horse. A second level of horse was the lady’s palfrey – often smaller and finer, but the medieval warhorse was not a giant farm horse, but a solid beast like a modern Hanoverian. Also, ronceys which are generally inferior smaller horses ridden by archers.

Hours – The medieval day was divided – at least in most parts of Europe – by the canonical periods observed in churches and religious houses. The day started with Matins very early, past nonnes in the middle of the day, and came around to vespers towards evening. This is a vast simplification, but I have tried to keep to the flavor of medieval time by avoiding minutes and seconds.

Jupon – A close fitting garment, in this period often laced, and sometimes used to support other garments. As far as I can tell, the term is almost interchangeable with doublet and with pourpoint. As fashion moved from loose garments based on simply cut squares and rectangles to the skin tight fitted clothes of the mid-to-late 14th century, it became necessary for men to lace their hose (stockings) to their upper garment – to hold them up! The simplest doublet (the term comes from the guild requirement that they be made of two thicknesses of linen or more, this ‘doubled’) was a skin-tight vest worn over a shirt, with lacing holes for ‘points’ that tied up the hose. The pourpoint (literally, For Points) started as the same garment. The pourpoint became quite elaborate, as you can see by looking at the original that belonged to Charles of Blois online. A jupon could also be worn as a padded garment to support armour (still with lacing holes, to which armour attach) or even over armour, as a tight fitting garment over the breastplate or coat of plates, sometimes bearing the owner’s arms.

Kirtle – A women’s equivalent of the doublet or pourpoint. In Italy, young women might wear one daringly as an outer garment. It is skin tight from neck to hips, and then falls into a skirt. Fancy ones were buttoned or laced from the navel. Moralists decried them.

Langue – One of the sub-organizations of the Order of the Knights of Saint John, commonly called the Hospitallers. The ‘langues’ did not always make sense, as they crossed the growing national bounds of Europe, so that, for example, Scots knights were in the English Langue, Catalans in the Spanish Langue. But it allowed men to eat and drink with others who spoke the same tongue, or nearer to it. To the best of my understanding, however, every man, however lowly, and every serving man and woman, had to know Latin, which seems to have been the order’s lingua franca. That’s more a guess than something I know.

Leman – A lover.

Long Sword – One of the periods most important military innovations, a double-edged sword almost forty five inches long, with a sharp, armour-piercing point and a simple cross guard and heavy pommel. The cross guard and pommel could be swung like an axe, holding the blade – some men only sharpened the last foot or so for cutting. But the main use was the point of the weapon, which, with skill, could puncture maille or even coats of plates.

Maille – I use the somewhat period term maille to avoid confusion. I mean what most people call chain mail or ring mail. The process was very labor intensive, as real mail has to have each link either welded closed or riveted. A fully armoured man-at-arms would have a haubergeon and aventail of maille. Riveted maille was almost proof against the cutting power of most weapons – although concussive damage could still occur! And even the most strongly made maille is ineffective against powerful archery, spears, or well-thrust swords in period.

Malle – Easy to confuse with maille, malle is a word found in Chaucer and other sources for a leather bag worn across the back of a horse’s saddle – possibly like a round-ended portmanteau, as we see these for hundreds of years in English art. Any person traveling be he or she pilgrim or soldier or monk, needed a way to carry clothing and other necessities. Like a piece of luggage, for horse travel.

Partisan – A spear or light glaive, for thrusting but with the ability to cut. My favorite, and Fiore’s, was one with heavy side-lugs like spikes, called in Italian a ghiavarina. There’s quite a pretty video on YouTube of me demonstrating this weapon . . .

Pater Noster – A set of beads, often with a tassle at one end and a cross at the other – much like a modern rosary, but straight rather than in a circle.

Pauldron or Spaulder – Shoulder armour.

Prickers – Outriders and scouts.

Rondel Dagger – A dagger designed with flat round plates of iron or brass (rondels) as the guard and the pommel, so that, when used by a man wearing a gauntlet, the rondels close the space around the fingers and make the hand invulnerable. By the late 14th century, it was not just a murderous weapon for prying a knight out of plate armour, it was a status symbol – perhaps because it is such a very useless knife for anything like cutting string or eating . . .

Sabatons – The ‘steel shoes’ worn by a man-at-arms in full harness, or full armour. They were articulated, something like a lobster tail, and allow a full range of foot movement. They are also very light, as no fighter would expect a heavy, aimed blow at his feet. They also helped a knight avoid foot injury in a close press of mounted melee – merely from other horses and other mounted men crushing against him.

Sele – Happiness or fortune. The sele of the day is the saint’s blessing.

Shift – A woman’s innermost layer, like a tight fitting linen shirt at least down to the knees, worn under the kirtle. Women had support garments like bras, as well.

Tow – The second stage of turning flax into linen, tow is a fiberous, dry mass that can be used in most of the ways we now use paper towels, rags – and toilet paper. Biodegradable, as well.

Yeoman – A prosperous countryman. Yeoman families had the wealth to make their sons knights or squires in some cases, but most yeoman’s sons served as archers, and their prosperity and leisure time to practice gave rise to the dreaded English archery. Only a modestly well-to-do family could afford a six foot yew bow, forty or so cloth yard shafts with steel heads, as well as a haubergeon, a sword, and helmet and perhaps even a couple of horses all required for some military service.

PROLOGUE

Calais, June, 1381

Evening was falling.

The air was soft enough for a man to stand outside clad only in his shirt, but winter’s arm had been dreadful and long and the bite of a chill was close. Men took advantage of it to stand in the inn’s yard and exchange blows with swords against bucklers, or to wrestle, or just to lift stones. When one of the inn’s young women went to the well, every male head turned, but there was a discipline to their postures and their tongues that went with the matching jupons and the warlike equipment.

The inn-yard gate began to open, and the men in the yard stiffened at the sound of heavy hooves striking the cobbles.

An old archer put his flask of wine behind his leather bag on the ground and gave a sharp whistle. Most of the activity in the yard came to a stop, but two pages continued to wrestle, and a tall squire put his boot into a wrestler’s hip.

‘Sir William!’ he hissed.

The gates came back against their wrought-iron hinges. The innkeeper, a prosperous middle-aged man who could have passed for a gentle in any town in Europe, appeared in the yard, hat in hand. He bowed as Sir William Gold entered the yard, six feet and a little of scarlet wool and black, topped by hair that, though going grey, still maintained a sheen of copper. Behind him, his body squire, John de Blake, carried his sword and helmet.

The innkeeper took the knight’s horse. ‘Vespers any moment, Sir William,’ he said. He nodded at the men in the yard.

‘Thanks, Master Ricard,’ Sir William said, and swung down from his horse. ‘Do I smell apples?’

Master Ricard grinned. ‘Apple pies, my lord. That have been making all the day. Last autumn had a fine crop.’ In Calais – the jewel in the English Crown of mainland possessions – Master Ricard’s Flemish-English was the norm, not the broad Midlands accent that William Gold used.

‘Well, it will have to wait until after Vespers,’ Sir William said. He looked around the yard, eyes passing easily over two young pages, who stood bashfully rubbing their hips and glaring at each other. ‘I’m sure you will all join me?’

A bell – from the church whose back wall overhung the inn yard – began to ring, carrying easily in the evening air.

‘Was your meeting at the castle … productive?’ Master Ricard asked carefully.

‘Hmm,’ Sir William replied. He saw movement coming out of the inn’s main door and he inclined his head. ‘Master Chaucer.’

‘Sir William,’ the other man answered. He was thinner – almost lean – in the rich black of a prosperous merchant, but wearing a heavy-bladed basilard, the mark of a fighting man in most circles, and as he exchanged bows with the red-haired knight they might have been a mastiff and a greyhound.

Chaucer bowed, a tiny smile lingering around his lips, as if he found something funny but was too well bred to mention it. ‘May I join you for church?’

‘Please!’ Sir William said. He took the other man’s arm and they walked to the gate, the men-at-arms and archers in the yard falling in behind them in order of rank – military rank, and in some cases social rank. John de Blake was a fully armed squire, outranking the pages and counting as a man-at-arms; but his social origins outranked those of most of the other men in the company, and he fell in behind his master. And the company’s master archer did not fall in at the head of the archers, but instead came last of all, using his will and his fists to move the slow and the unlucky past the long brick wall and into the nave of the church – the long, high nave.

The church, Notre Dame of Calais, started by Frenchmen and completed in a very English style, was big enough to silence even the most boisterous page. A trio of priests began to sing, supported by the chapter, who had seats. Everyone else stood – even famous English knights.

‘You had trouble at the castle?’ Chaucer asked.

Sir William was telling beads on his paternoster, his breathing deep and regular.

Chaucer looked away impatiently. He kept his head still and let his eyes wander – took in a pair of monks whispering where they thought they would not be heard; noticed a pretty nun smoothing her habit; eyed a pair of Sir William’s pages the way a predator might watch prey: observing, cataloguing, listening.

The second psalm was taken up; the cantor’s voice strong and powerful as a trumpet, and the chapter responded, and the congregation took up the Agnus Dei.

Chaucer sighed.

Sir William sang. In fact, he sang well, and his Latin was good. Chaucer smiled to himself.

Later, Sir William knelt, his arming sword’s tip resting on the stone floor as lightly as the older knight’s knees appeared to rest. Chaucer went to one of the mighty pillars that supported the nave and leaned against it to watch the nuns, who in turn watched the men-at-arms.

Sir William’s lips moved slowly, and then his breathing deepened, and then he was a still as a statue, or a stone memorial to a dead knight.

Chaucer rolled his eyes and fidgeted. But his eye caught a pair of older nuns hissing at each other, and he shifted himself until he could catch their middle-aged invective, their careful avoidance of the appearance of anger, their false humility.

‘You don’t think very highly of your fellow man, do you, Master Chaucer?’ Sir William asked.

Chaucer had to cover a start – the big red-haired knight moved very quietly. ‘You pray for a very long time,’ he said.

Sir William shrugged. ‘I have much for which I should atone. A moment of prayer is a small sacrifice.’

‘You had troubles at the castle,’ Chaucer said.

Sir William’s mouth made a curious gesture, as if it could not itself decide whether to frown or smile. ‘Brian Stapleton is leaving to take up the captaincy of Guines.’

‘That’s Miles’ brother? Surely you two are old friends and good companions?’ Chaucer managed a genuine grin. ‘You and Miles fought Saracens together.’

‘He’s being replaced by John Devereux. Something is afoot at home, and Sir Brian is unwilling to give me a passport.’ Sir William shrugged again. ‘I was summoned by the king. I am needed in Venice and my patience has limits.’

Chaucer nodded, and the two men walked past the nuns, who now kept their eyes down and their movements discreet. Outside, darkness was falling, the air was chill, and the smell of baked apples and sugar carried like the scent of love.

Sir William laughed. ‘I’m imagining myself the centre of the world. Why are you still here?’

Chaucer grunted. ‘The same. The French have not prepared me a pass, even though my business is to their good.’

‘Peace?’ Sir William asked.

‘At least a longer truce. There are those at home who would push the young king to war – but the truth is, there’s no money and no will to war in the commons.’ Chaucer gazed into the darkness.

Ahead of them on the street, a woman was lighting the lamps on her house. She inclined her head as they passed, and Sir William bowed deeply to her and gave her the sele of the day, to which she responded by blowing him a kiss.

‘You are the lovesomest man,’ Chaucer said.

Sir William smiled. ‘I do love women, it is true,’ he said. He watched the goodwife as she stretched to light her last lamp.

‘Adultery is a sin,’ Chaucer said.

‘This is very monk-like, coming from you,’ Sir William shot back.

The two of them turned the corner of the church of Notre Dame and walked slowly toward the inn gate, visible at the end of the lane.

‘If we’re here another night, perhaps we can spin Monsieur Froissart more tales of our misspent youths,’ Sir William said.

Chaucer laughed. ‘I believe that the two of us are too far beyond Monsieur Froissart’s views of the world.’ He looked at Sir William in the torchlight. ‘Do you remember him from Prince Lionel’s wedding?’

Sir William nodded. ‘No. But I was busy, then. Well, if he’s determined to listen, we could do him some good. I could tell him of the Levant.’

‘And the Italian Wedding,’ Chaucer said. ‘Sweet Christ, that was a horror.’ He grinned mirthlessly. ‘He was there, but he didn’t see our side of it.’

‘Not all a horror,’ Sir William said. But when their eyes met, something passed – some shared thing.

‘You tell tales for your living,’ Sir William said. ‘Why leave me to tell the story?’

Chaucer took his turn to shrug. ‘I like to see what you do with it. You take all the blood and shit and make it into something. As if it mattered.’

Sir William paused, his hand on his paternoster. ‘Of course it matters,’ he said. Then he paused. ‘It matters to the men who are in it. Even when the cause is worthless.’

Chaucer grimaced. ‘You would say that.’

An hour later, and they were served a series of dishes – a meat dish with noodles, a game pie, a dish of greens. The inn’s food was renowned wherever Englishmen gathered, but it was not all English food, and the greens showed the influence of the new French fashions: fresh food, in season, and especially vegetables.

Chaucer eyed his beet greens with a certain distaste. ‘French clothes, French manners, and now French food,’ he said. ‘You’d think we’d lost the war.’

Messieur Froissart, on the other hand, inhaled his with every evidence of pleasure – or perhaps the hunger of a poorer man.

Sir William put a pat of butter on his and ate them quietly. ‘In Italy,’ he said.

Froissart quivered like a hound.

‘My faith!’ Sir William said, and laughed. ‘I wasn’t going to speak of fighting, messieur, but of food! In Italy, Sir John – Hawkwood, that is – has introduced an English dish, a true beefsteak, and it is all the rage, although they serve it with their own vegetables and salts. In truth, it seems to me that every country benefits in borrowing some food from their neighbours.’

Chaucer shrugged. ‘Mayhap, William, but travel turns my ageing guts to water and I don’t need a boil of green weeds to soften me.’

Froissart, endlessly fascinated by Sir William, ignored the English courier and leaned forward. ‘And Saracen food? You are a famous crusader.’

Sir William looked up to meet the eye of Aemilie, the serving girl and the landlord’s eldest. He smiled, and his eyebrows made a little motion; she returned the smile, and curtsied.

‘My pater says to serve you this,’ she said. ‘And says to add that it was sent down from the castle for your enjoyment.’

Chaucer looked up. ‘Come, that’s handsome. Stapleton can’t expect to keep you here forever, if he sends you a nice Burgundy.’

Sir William tasted the wine in the heavy silver cup set before him, and his eyebrows shot up. ‘Bordeaux,’ he said.

Aemilie poured for Chaucer and then for Froissart, and the three gentlemen drank.

‘That’s a fine vintage,’ Chaucer said. ‘But after all, you did save his brother’s life.’

Again Froissart leaned forward in anticipation.

Sir William spiked the last bit of his meat pie on his pricker and ate it, drank some wine, raised an eyebrow at Chaucer. Chaucer shook his head. ‘It’s your tale,’ he said. ‘I was only there at the end.’

Aemilie was pausing in the doorway of the small dining room, waiting to hear whatever was said. Outside, Sir William could see his squire, John, and a number of other men. He swirled the wine in his cup.

‘If I’m allowed a full ration of this apple pie,’ he said, ‘perhaps I’ll tell a tale – but out under the rafters, where all can hear. Master Chaucer, do you play piquet?’

‘Not with professional soldiers,’ Chaucer said.

‘Fie!’ Sir William answered, and again they exchanged that look.

Froissart leaned past Chaucer. ‘Tell us about your crusade,’ he said.

Gold smiled his wolfish smile, and stroked his beard. ‘Very well. But I hope you are no fan of Robert of Geneva.’

Chaucer narrowed his eyes.

So did Sir William.

VENICE

1364

In the spring of 1364, I had just been knighted on the battlefield by that two-faced bastard, the Imperial Knight Hans Baumgarten, for my feat of arms at the siege of Florence. Except, as you know if you’ve been listening, there was no siege and we never had a chance to take the city. Five thousand men against a city with a hundred thousand citizens?

And the aftermath of my great deed was bitter; most of the companions, the Englishmen and Germans who had formed the great company that had made war on Florence for Pisa, accepted bribes and changed sides. There were fewer and fewer of us with Hawkwood – even Baumgarten himself, one of the most famous soldiers of our day, took the gold and crossed the river to join the Florentines.

Sir John Hawkwood didn’t change sides. Some say this is because of his honour. That’s possible – he had a solid view of his own worth, and no mistake – but for my money, he stayed loyal to Pisa because they’d made him their Captain General and that meant promotion. He had never been the sole commander of an army before, and he knew that if he could stick it out and attract men, he’d make a name that would mean employment and real money, not the forty florins a month that most of the men-at-arms earned, if they didn’t take a wound, lose their horses or pawn their armour or get the plague or fall prey to the hundreds of perils that beset soldiers.

At any rate, I stuck with Sir John. If you’ve been listening, you know he saved me once or twice, and despite being the devil incarnate in many ways, I liked him. And I still do. But by late May, we were down to two hundred lances or perhaps fewer. And that’s when Fra Peter came into our camp – Fra Peter being a Knight of the Order of St John that most men call the Hospitallers. Fra Peter brought me orders from his superior, the Grand Master; from Father Pierre Thomas, who had saved my soul, and from my lady, who I loved par amours – Emile d’Herblay. I won’t tell you which of those three held the highest rank in my heart, but I will say that the three together pulled far more weight at the plough than Sir John. And since tonight’s story will be about fighting the Saracens, let me begin where the story truly began; in Sir John’s pavilion outside Pisa, in May of 1364.

Sir John seldom displayed any emotion at all, and if the loss of two-thirds of his lances troubled him, he never showed it. Neither did he drink, or wench. That is, he liked a maid as much as the next man, but he was unwilling to show weakness – any weakness. His clothes were always perfect, and his horse was always groomed, and he did not lie abed, nor did he let us spy a pretty thing between the blankets of his camp bed. If there was one such, I never saw her. Indeed, he kept much the same discipline of the brothers of the Order, with none of their piety or purpose.

His squire served me wine.

‘How much have they offered you?’ he asked.

I shook my head. ‘It’s Fra Peter,’ I insisted. ‘I’m off for Avignon.’

He fingered his beard. ‘I can let you have a hundred florins if you stay.’

Now, this felt odd. First, I knew I was leaving with Fra Peter. If Emile was going on pilgrimage, I was going to be with her. And I had sworn to a living saint to go on crusade when my Order called me.

And a hundred florins was no longer so very much money. I had a surprising reserve of money in my purse, and a gentleman-squire to carry that money, and an account with the best Genoese bankers that could get me cash anywhere in the Christian world and pretty far among the paynim.

‘I’m not going with Andy,’ I said. ‘I’m off to fight the Saracens.’

He held up an ewer of wine, voicelessly asking if I wanted more wine. I nodded.

‘At least you have the honour to come and face me,’ he said. ‘But if you are riding with Walter Leslie, you might as well tell me.’

I knew of the Scottish knight, Sir Walter Leslie. I knew his two brothers, Kenneth and Norman, as well. We’d all served together in France. Sir Walter had the ear of the Scottish king, and the Pope, and he was across the river. That is, with the Florentines.

‘I’m not going with Sir Walter,’ I said.

‘He says he’s recruiting for the King of Cyprus,’ Hawkwood said. He drank a little more. ‘But right now, he’s in the pay of Florence. Stealing my men. For the fucking Pope.’ He looked at me. ‘If you go with him, you are, in effect, leaving the service of the King of England for the King of France.’

I was used to this; Sir John had the habit of using patriotism against us. And I knew – none better, as Master Chaucer will allow – that Hawkwood was always the king’s arm in Italy. ‘I thought we were serving Pisa against Florence,’ I said.

‘Florence is aligned with the Pope, who is raising the French king’s ransom,’ Sir John said.

I smiled, then, because Fra Peter had passed me a titbit of news when he gave me Emile’s letters, and I had assumed Sir John already knew it. But he didn’t.

‘King John of France is dead,’ I said.

Hawkwood froze for a moment. And for the first time in the conversation, his eyes met mine. ‘Says who?’ he asked quietly.

‘Fra Peter Mortimer,’ I said.

Sir John pursed his lips, but he didn’t protest. The Hospitallers had superb sources of information – they were the Pope’s mailed fist, and their intelligencers, too.

‘And you go to Avignon,’ he said.

I nodded.

He took a deep breath. ‘The Spaniard and the Friulian are donats, too. But I can’t let you take my master archer and ten lances. Nor Courtney nor Grice nor de la Motte. I know they are your men, but by God, William Gold, if you take all your companions, I’ll lose the rest by morning.’

‘I’ll come back!’ I said.

He embraced me, one of perhaps three times he did so. ‘Perhaps,’ he said. ‘If you don’t – God be with you.’

John Hawkwood embraced me and invoked God. My eyes filled with tears, but I clasped his hand and left the tent.

Say what you like about John Hawkwood: he could have mad

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...