- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

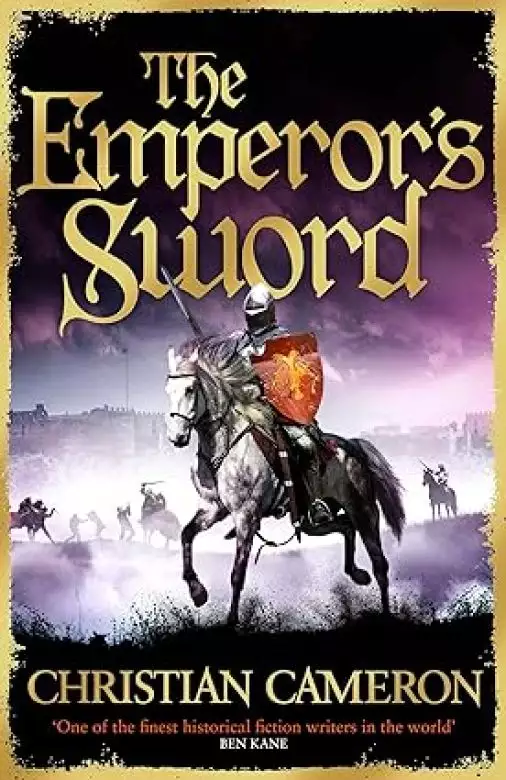

The penultimate instalment in the Chivalry series from a master of historical fiction.

The Chivalry series follows young William Gold, who runs away from London to follow the Black Prince, from the killing fields of France, through life as a routier and criminal, and to redemption with the Knights of Saint John, further disillusion and an eventual career as a professional soldier and knight. Rich in the details of life in the High Middle Ages, the series also deals with modern issues about the role of violence in society, rules of conflict and war, and the price that people pay for using violence.

'One of the finest historical fiction writers in the world' BEN KANE

Release date: April 25, 2024

Publisher: Orion

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Emperor's Sword

Christian Cameron

1372-73

A KNYGHT ther was, and that a worthy man,

That fro the tyme that he first bigan

To riden out, he loved chivalrie,

Trouthe and honour, fredom and curteisie.

Ful worthy was he in his lordes werre,

And therto hadde he riden, no man ferre …

As wel in Cristendom as in hethenesse,

And evere honoured for his worthynesse(;) …

Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales, ‘The General Prologue’

In the spring of the year of Our Lord 1373, it seemed as if the world had been turned upside down, and all the players in the great chess game of Italy had been shaken in a hat and placed on the board in different colours – red was suddenly white, and white red.

If you recall, and I have to look at notes to remember myself, the summer of 1372 had placed Hawkwood, with his company, on the side of Milan against the new pope, Gregory, the eleventh to take that august name on climbing into the seat of Saint Peter, or at least the Avignon substitute. Gregory was an inveterate enemy of the Visconti of Milan, who reciprocated his hatred with their own vipers’ venom. And the war they fought wandered between hot and cold like a sword blade being forged and quenched, forged and quenched. You may recall that I saw the results of Albornoz’s defeat of Hawkwood in ’68, and then later, we stood with Bernabò of Milan against the Pope and the Emperor at Borgoforte. Through all of this, I was serving with Hawkwood, but I was serving my feudal duty for the Count of Savoy, who was, and remains, my feudal lord, despite some bumps and mishaps.

Regardless, we gave good service to Bernabò, and he returned our service with promises and very little gold. And I will probably repeat myself a hundred times on this subject, but it is very expensive to keep a company in Italy, or France, or any other theatre of war. It beggars belief how many iron buckles, leather lace points, feed bags, and scabbard tips a company can use – aye, and lose – in a month.

Listen, friends, because this is the essence of my tale. There are really two kinds of companies, and they are much the same whether they fight for a great lord for feudal duty, for a town for pay, or for themselves as ‘Free Companies’. That’s correct, Master Froissart, and I will insist on this point. Either they have the training and discipline to maintain themselves, with regular food, good forage for horses, new iron buckles for well-worn harness, scabbard tips on scabbards and rust polished off armour … Either they have pride and discipline, or they don’t, and they are a mob of dangerous rogues bent on murder, rape and destruction. It is the great pity of our time that most employers care not a whit which kind they employ, as either will do in many situations. And it is the sin of my life that, having led the first kind of company, I almost let my lances become the second kind, as you shall hear.

And sadly, Master Froissart, it’s all about money. Of course, it’s about chivalry and training, too, but ultimately, if you don’t pay your hired killers, they tend to take what they need, and that way crime and mindless war lie.

So, in the autumn of the year of Our Lord 1372, Sir John Hawkwood, by then one of the most famous captains in Europe, gathered his two hundred unpaid lances and left the armies of Milan, and joined with our army for the winter. I was there ahead of him by arrangement, as you may recall. I even played a small role in getting him to come over to the Pope, although, to be fair, he was inclining that way all summer, even as we won a great victory at Rubiera over Galéotto Malatesta and Niccolò d’Este. A great victory that harmed the Pope and seemed to suggest that victory was in the grasp of Milan.

Right? Everyone caught up? I promise, a cup of wine helps. Italy wasn’t a cesspit like France, but it was complex enough, for all God’s love – and it still is. Consider, gentles … Florence, Milan, Genoa, Rome, Bologna and Naples, every one of them as rich and powerful and populous as London or Paris – more so. Venice and Genoa are richer than England or France. Milan is richer still. The Pope is made of money – imagine having one tenth of all the minted money in all of Christendom. And the smaller cities like Verona, Pisa, Siena … almost as rich as London. So imagine ten Englands and ten Frances packed into a very small area, and you have Italy, with all the money, and all the war.

And in the winter of 1372, we were laying out the board for a fresh round. You’ll remember that in 1368, everyone thought we were headed for the ‘Great War’ of our time – a war that would engulf all the cities in Italy, as well as the continental powers and England. It started … and then fizzled.

Just before Christmas of 1372, the Pope excommunicated all the Visconti. And if you were listening, you know how richly they deserved it, and how happy it made me, and I saw the hand of Isabella of England in it. Daughter of King Edward the Third, sister of the murdered Prince Lionel, Duke of Clarence, wife of Enguerrand de Coucy, reputed Europe’s greatest noble and our commander in the field, Isabella had the political power to attack the Visconti, and thanks to a few of us, she had the proof she needed to know how her brother died. I said all this last night, but I want you to remember, because the ripples of that murder roll on like waves from a storm, to this very day, and because my refusal to forgive the Visconti led … Well, you’ll see.

At any rate, one more time. At Christmas of 1372, we were preparing a great army for the Pope. I was still serving as a feudal lord for Amadeus of Savoy, but my lances were in the pay of the Church now, serving directly with Hawkwood. I had fifty lances of my own. Every lance had a fully armoured man, an armoured squire with most of the harness of a ‘man-at-arms’, an archer or crossbowman, and a page. The core of my people had been with me since Jerusalem – Marc-Antonio, my former squire, Pierre Lapot, a close friend, Etienne l’Angars, my corporal, Gaillard de La Motte, Grice and John Courtney, Father Angelo and a dozen others. I still had some of my veteran archers, too – Ewan the Scot, Gospel Mark, Sam Bibbo, my master archer, and even Witkin, a strange man who had nonetheless become one of my most trusted companions.

And I had relatively new men, too – the Greek archer Lazarus, a Cumbrian veteran named Dick Thorald whom I could barely understand, Greg Fox, a London tailor’s apprentice, and Tom Fenton, once a penniless young man and now a fashionable man-at-arms. I still had Benghi and Clario, the incorrigible Birigucci brothers, and their terrible page Beppo, and a dozen more, including Christopher, my squire and master horse thief, a dark-skinned man who claimed to be from Aethiopia.

And Janet. Lady Janet, Ser Janet – a woman in the world of chivalry. Janet and I had been together as comrades since the days of the ‘White Company’. She liked to fight, and she liked to be a knight, and she was a noblewoman where many of us were the merest routiers. She could do figures and cast accounts, and she kept my lances paid and fed. Which was wonderful, nigh on a miracle, because it’s not my strongest suit, I confess it.

And Pilgrim. He scarcely comes into this story, but he had become my company’s dog, not just mine, and he was gaining weight as fast as he made new friends at camp fires.

And Fiore? You might well ask, as he was close to being the best friend I’d ever had, saving perhaps Richard Musard. But Fiore was back in Udine, a mountain town whose populace was renowned throughout Italy for violence. He’d promised to join me ‘in the spring’ with a few lances of his own, but I hadn’t seen him in months, and had received no word.

Fifty lances! I was just learning how much hay fifty lances could consume – and how much grain, and how much meat, and how much wine. I’d never really had much more than twenty lances, and the potential for profit was magnificent, but the potential for financial ruin was just as great. If you imagine that a lance was paid twenty florins a month – sometimes less and sometimes more – then my fifty lances were due a thousand florins a month, from which they were expected to find their own food and fodder, except that … ahem … it didn’t usually work that way, and we tried at all times to feed ourselves from the enemy. To increase profit, and discomfit the foe. Naturally.

A thousand florins a month was perhaps ten times my monthly income from my estates in Savoy. I did receive occasional incomes from Cyprus and Lesvos, but they were infrequent and didn’t amount to much.

I’m being long-winded, but here’s my point. I had reached a stage of my career as a knight – as a soldier – when I could no longer easily support my own men out of my pocket. Even my beloved Emile would have struggled to pay fifty lances for a whole campaign season.

As a side note, Catherine of Siena, the most blessed woman in Italy and a living saint, often demanded that all of the mercenaries and Companies of Adventure go on crusade. Holy woman that she was, she didn’t understand that such armies would have to be paid for – not so much because of the greed of mercenaries, but because men and horses have to eat.

I’ll be returning to this point many times, because until the Christmas of 1372, my own company had been small, and it had always been paid well by Nerio, and by the Count of Savoy, and protected from starvation by my magnificent wife, who did have the estates required to cover all of their expenses. But she died of the plague in a church in Piedmont, and I left the direct service of Savoy to serve John Hawkwood and the Church. I had more than doubled my numbers – with good men, veterans, carefully chosen with Janet’s help, and Bibbo’s, and l’Angars’s.

So as the Pope’s army gathered around Bologna, my thoughts were increasingly in the account books that Janet carried in her saddle malle. While I took every opportunity to play at lance and sword with my people, I was becoming accustomed to reading numbers and shopping for forage. Because that is the real life of a captain at war – every day, it’s food, forage, shelter.

Bah. You want to hear of battles.

Well. 1373 was a very good year for battles, as you shall hear.

We were on the Pope’s payroll, and we’d been promised double pay for the first two months of our contract. I myself was receiving almost three hundred florins a month as a chief officer under Hawkwood, and we were brigaded with, of all people, Niccolò d’Este, the lord of Ferrara, who had just been our opponent the year before. In fact, we had in the same army – or at least on the same side – Malatesta, Este, Hawkwood, Amadeus of Savoy, his cousin the Count of Turenne (no friend of mine), Otto of Brunswick, and a small host of Gascons under Amanieu de Pomiers. And our commander, Enguerrand de Coucy. I mention the last, because we’d become friends – at least as much as a great noble and a former assistant camp cook can become friends. He kept magnificent state in the camp, and I was welcome at his table, and I often took Janet with me, as she knew everyone in France.

You might have thought we’d be unwelcome with Este and Malatesta, as we’d pinned their ears back at Rubiera the year before, but in fact, there was no such rancour, beyond Malatesta’s slowness in paying his ransom. I’d taken him at Rubiera and sold him to Sir John, who still hadn’t paid me.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

We were under the walls of Bologna in late winter, and Coucy had the most magnificent tent I’ve ever seen – really more like a castle in miniature, with three great pavilions joined by halls of double-walled canvas lined in tapestries and carpeted in Turkish rugs. He had a hanging bucket by his bed for water, and lanterns of brass and bed hangings of velvet, and the prettiest Madonna hanging by his bed. Altichiero had done her, and she was magnificent, and also bore a stunning resemblance to Lady Isabella, the King of England’s daughter and Coucy’s wife.

His pavilions were studded with braziers that were kept lit by a horde of servants and burned incense as well as charcoal. Janet and I spent so much time there because it was warm, in addition to the pleasure of his company.

We were sitting at his long table – I believe we’d all just celebrated the Feast of Epiphany in Bologna. Coucy had the biggest, longest camp table I’ve ever seen, five or six ells long, kept for his ‘peers’, the name he had for his intimate friends. This was a man who had friends – his social skills were on a par with his military prowess. He had friends who were brilliant knights, and friends who were poets, and friends who were simply travelling. Janet and I were lucky to be admitted among them. It was at that table that I met Altichiero, the Veronese artist. I’ve been told that Boccaccio sat there glowering one night, sad and ruffled, like an old hawk, because he was on his way home from Petrarca’s funeral.

And Hawkwood. As was the way in those days, Coucy, as one of Europe’s greatest noblemen, was the commander of the papal armies of Lombardy. The Green Count, my sometime feudal sovereign, was away in the north, fighting the Visconti from his own lands, but Hawkwood might have resented Coucy getting the command, as he was older, and at that point he was at the height of his military powers. But the Pope liked aristocrats, and felt that mercenaries were untrustworthy, which was, I suppose, both naive and foolish. But in 1372, no one appointed a mercenary as commander, although all that was to change.

Coucy had the good grace to make light of it, and to consult Hawkwood on almost every issue – and not just Hawkwood, but Malatesta and Este and others. He had the gift of making every man feel singled out, included, consulted. In many ways he was the antithesis of my Count of Savoy – where Amadeus pronounced, Coucy enquired.

Let me add that both leadership styles appealed to me – they both work. One might even argue that the Green Count consulted in private and pronounced in public, where Coucy consulted in public and pronounced in private … a mere matter of style.

But, as usual, I digress. It was early January. The Magi had found the Christ child, and we’d all exchanged gifts. Janet and I were still on edge with each other, tempted by carnality and fully aware what the costs would be. Otherwise, my life was as happy as it could be with Emile gone. Janet and I were seated, as I say, at Coucy’s long table, and it was warm. My Turkish kaftan lined in wolf fur was hanging off my shoulders, and I was playing with Charny’s dagger, when Hawkwood leant over the table. We’d recently been joined by an exile from Piacenza, Dondazio Malvicini Fontana, who was to ride with Hawkwood. He was a little too angry for my taste, but I barely knew him, and he’d begun to harangue us all in his enthusiasm for what he called the ‘liberation of Piacenza’, and my attention wandered as I thought about things. Mortality. My dead wife. My children, growing up without me. My son by Emile, being raised in Savoy. I needed to … to …

‘Gold, are you asleep?’ Hawkwood snapped at me.

Coucy smiled.

I could hardly say, ‘I was thinking about my dead wife and my failings as a parent,’ so instead I apologised.

‘I was just saying that I thought we should make a run at the Via Emilia, and Sir John …’ Coucy waved at Fontana.

‘You came down the Via Emilia in summer, young William. What do you say?’ Sir John asked.

I had a glass of very good wine. It was a beautiful glass that came in a fine leather case, and had been my Christmas gift from Janet. It was a pleasure just to hold it. I looked at Fontana, and then at Sir John.

‘If we sent an advance guard to seize the bridges,’ I said, ‘I think we could move quite rapidly.’

‘Just so,’ Coucy said. ‘You can repeat all your exploits of summer, but going in the opposite direction.’

Malatesta, who was present, roared a laugh. He was easy to like, for a big bruiser of an Italian knight.

‘For my part …’ Sir John said carefully. He looked around, to see if all these great nobles were listening. It was fascinating to see Sir John hesitant. I was used to him being unafraid of anything, but he genuinely seemed to desire Coucy’s good opinion – perhaps because he was King Edward’s son-in-law, or perhaps merely because Sir John was a little in awe of his rank and repute. ‘For my part,’ he said again, ‘I worry that as we move on Visconti lands, they will come at us.’

‘Surely they will face us in Lombardy,’ Coucy said.

‘The Visconti have very little chivalry to begin with, and it’s spread thinner when they’re losing, like too little butter on too much bread,’ Sir John said. ‘I think you’ll find they’ll ignore us and raid the Pope’s lands, rather than facing us in the field.’

Malatesta shrugged. ‘It may be as you say,’ he said, indicating how little he cared for the peasants and merchants of Papal Lombardy.

Este made a face. ‘You think that if we march to the gates of Piacenza, Bernabò will simply ignore us?’ he asked.

Sir John smiled his fox’s smile. ‘Do we have a siege train? And the men to take Piacenza?’

Coucy remained silent, but at this sally his eyebrows shot up.

‘What do you mean?’ he asked.

I thought Fontana was going to explode. ‘The city will fall into our hands like a ripe plum as soon as we approach,’ he said.

Coucy’s look was perfectly bland, but I knew the man well enough to know that he didn’t believe this any more than Sir John.

Sir John looked at me. I thought he deserved some support.

‘My lords,’ I said, ‘I am the least commander here, but as a swordsman I know that if my point does not truly threaten my opponent, he can ignore my blow and work his own will. I think Sir John merely says that if we lack the means to really hurt the Visconti, they are free to ignore us. I can say from experience that outside their personal fiefs, they care very little what happens to their subjects.’

Malatesta winced.

Este shrugged. ‘Who cares?’ he asked. ‘I mean, does the Pope really expect us to destroy the Visconti?’

Silence greeted this sally, as Este had committed the social sin of speaking a truth we all understood but none of us was supposed to say aloud. The war was devastating the peasants of one of the richest places in the world, but the two contestants, the Pope and the Visconti, were almost impossible to injure, and that meant the war was being fought by proxies like us, with money. The peasants were doing all the bleeding.

Ugly. I saw it quite clearly, and it made something go hollow in the pit of my stomach.

Janet laughed. ‘Why bother?’ she said. ‘I mean, we could simply sit here, and let them sit there. Everyone would be happier.’

Coucy smiled at her. ‘You always were a clever one,’ he said.

She shook her head. ‘The most expensive war in my generation, and what have we accomplished?’

‘A little too honest,’ snapped Sir John, as we rose to leave. ‘Janet, these are great lords …’

‘Yes, John,’ she said. ‘I grew up with them.’ Unlike you, she left unspoken.

Two days later, Hawkwood led us – by which I mean all the English and some of the Italians – out of comfortable winter quarters, and we marched west, on the Via Emilia. It was like a re-creation of the year before, except that this time we were the papal forces, and we had all the major towns – Modena, Reggio Emilia, Parma. Bernabò’s forces were nothing to sneer at, as he had most of the good German captains, but they retired steadily as we moved along the road, our horses’ hooves ringing on the frozen ground like an armourer’s hammer on the anvil. At first we had food everywhere, because Bernabò’s men had made themselves thoroughly disagreeable all winter. While Bernabò was personally a beast, I suspect the Germans behaved badly because they hadn’t been paid.

If raiding peasants reminded me a little too much of France in the fifties, and made my stomach feel empty, unpaid bills left much the same feeling. It was Saint Crispin’s day, according to the mark in my book, and we’d just missed another pay day. That is, Sir John hadn’t been paid, so that I hadn’t been paid. I arranged with my bankers and Janet’s good offices to pay everyone else in my fifty lances, and I did so in Castelfranco, on the road to Modena, because my little company was being sent to grab the bridges. I took a risk and moved my money there to pay everyone, away from Sir John’s much larger company. Sir John had been joined by one hundred lances under Sir John Thornbury, a solid man with an excellent reputation, and Sir John, through his various contractors like me and Thornbury, had almost six hundred lances – two thousand mounted fighting men of his own. By contrast, Coucy had a few more than three hundred lances.

I’m leaving my road again, but all this matters, because I was paying my people from my own estates in Savoy so that they weren’t tempted to rape, murder and rob. Sir John affected not to care for such niceties, but I noticed that he happily used my troops for his advance guard. And the point is that I paid out a little more than fifteen hundred ducats in gold. That’s about a year’s income from my estates, or one sixth of my worldly goods in 1373, to pay my lances for one month. Just one.

However, we left Castelfranco with the whole company, from Witkin to Janet to Christopher, by my side. We were in fine fettle, with good plumes in our helmets and big new wool cloaks over our bright armour. Lombardy isn’t big on snow, but it is cold enough, by the Virgin. And as we rode out, I had a happy meeting, because there was my friend Sister Marie on a mule, with a dozen churchmen around her and an escort of Papal men-at-arms, all of them moving to protect their charges with drawn swords from my compagnia. We were, after all, the notorious ‘English’.

But Sister Marie called out, ‘I know these men,’ and Father Angelo rode forward from our ranks with his rosary wrapped around his hand.

We shocked the priests and monks with a hug.

‘Where are you bound?’ I asked.

She nodded. ‘I’m joining these worthy men to examine an early gospel,’ she said with a brittle smile.

‘Sister Marie’s Latin is surprisingly good for a woman,’ a Benedictine said. From his tone of voice, you might have thought he meant a compliment.

A Dominican friar in a spotless white robe merely glared. ‘Son of Belial,’ he spat at me. ‘Get out of the road.’

Ah, the Church does excel at making itself loved. All those servants of the gentle Jesu.

‘Are you going west?’ I asked.

‘To the monastery of San Raimondo in Piacenza,’ she said.

‘You’re riding into a war,’ I said.

The bishop, who I had taken for a captain of men-at-arms, pushed his horse through the press.

‘Who are you, and by what right do you delay us?’ he snapped in aristocratic Roman-Italian.

I bowed. ‘I am sorry to delay you,’ I said. ‘This esteemed sister and I made the Camino di Santiago together.’

By then, Sister Marie was embracing Lapot, and I had spotted Michael des Roches, attired in a severe brown cote. I went forward to clasp his hand, but the bishop grabbed my arm.

‘I find you shockingly rude,’ he said.

I turned, brushed his hand off my arm, noting that he had rings over his gloves. I thought of many things to say and do, but I suspected that Sister Marie would be made to pay for any display of temper.

‘I’m sorry, my lord, but these are dear friends. We will clear your way in moments.’ I smiled, kept my hand from my sword hilt, and turned my horse.

But the bishop insisted that his party ride on, and he was loud and angry and got his way. The religious troop vanished up the road to Crevalcore, and we turned due west towards Modena. Sister Marie rode past me. Her extended arm blessed me, and I was pleased to see that she had a sword strapped to her mule’s saddle under her thigh.

‘I have someone for you to meet!’ she called out.

The bishop glared at her, and Michael des Roches smiled. I remembered that smile from great days and great conversations – a smile that announced that the scholar had something interesting to say.

I saluted him, and we rode on.

We rolled west, with our prickers out ahead, covering the miles. I had a dozen guides, all kept separated and all reporting to Sam Bibbo and Lapot, and flankers out as far as the villages to east and west, watching the cart-roads and the lanes. Lapot took a dozen archers, a few old routiers like himself, and my squire Christopher and rode well ahead. We’d find his people left as guides for us, or we’d glimpse them on a hilltop to the north, but that was seldom. Usually we just knew they were ‘out there’.

Modena, Reggio Emilia, and right to the walls of Parma.

Outside Parma, my people made camp on the west side of a big ditch – whether a stream or an old irrigation ditch, I don’t know. Janet proceeded to set up a market to purchase grain and fodder, which was our method of gathering information, and also keeping supplied. The local peasants had borne the brunt of the war, as armies slogged up and down the Via Emilia, and they were shy of coming into our camp until guarantees were made, a process in which Father Angelo played a role. He had declined to return to being a minor priest in Verona, especially as his family were on the outside of the local politics, and he had in effect adopted Sir John’s entire army as his ‘parish’.

All this to explain that it was evening and my people didn’t have fodder for their horses yet. I walked into the ‘market’ to find out what was holding up the feeding of horses and cooking of soldiers’ food, to find some very angry peasants haranguing Father Angelo and Janet.

I was in my usual evening campaign attire – an ancient wool gown that couldn’t even remember better days, arming hose so worn that they were more stuffing than quilting, and shoes so light they were like slippers. After a day in armour, I just wanted to be light as air – ageing, I suppose.

Regardless, I slipped in with the farmers unnoticed.

‘Maybe if we didn’t feed the bastards they wouldn’t come back,’ a young, angry man said.

‘Ye’re daft as a newt,’ said an older man. ‘If’n we don’t come sell ’em our grain, they just come an’ take it, like.’

A dozen mounted archers sat on their horses at the back of the queue of wagons – and explained the surliness. I pushed through to the table where Janet sat with our notary.

‘Trouble?’ I asked.

She looked up. ‘They really don’t want to sell us grain,’ she said. ‘Bad harvest, and last year’s campaign stripped a lot of these farms.’

One of our new Italian knights was a cousin of Father Angelo – Giorgio Cavalli. He was young and a ‘true believer’, by which I mean he was a political adherent of the Pope and hated the Milanese. Ser Giorgio was standing armed behind Janet, and he heard the bickering of the farmers.

‘We are soldiers of His Holiness the Pope!’ he roared. ‘We are come to protect you from the Viper of Milan!’

He was met with the sort of stony silence usually reserved, among farmers, for tax collectors.

‘Are you fools? Can’t you raise your noses above your dung heaps to see that—’

Father Angelo rose from the table and clapped a hand over his cousin’s mouth.

‘They are angry enough already,’ he spat.

The older man who’d spoken out in favour of selling us grain now looked at me. ‘You’re all the fuckin’ same to us,’ he said. ‘Bandits with armour.’

Stung, I pointed at Janet’s table and the piles of silver coin – my silver coin, let me add – waiting to pay for the forage and grain.

‘We pay for what we take,’ I said.

‘Aye, at Bologna market prices. And if this empties my barn, where do I get more?’ the man asked. ‘Four fewkin’ years o’ war, mate. Four years you’ve cleared me out. My woman an’ I ate onions last winter. Fuck you, and fuck the Pope. And the Vipers. Hope you all burn in Hell for eternity.’

I was rocked back as if he’d hit me. For a moment, all I could think of was the nuns screaming at us in France, a long time ago – a moment that is still with me, by the saints. I was, by 1373, a knight of some renown – a man who’d made pilgrimages and a crusade, fought in tournaments, fought under the eyes of my prince. I was no longer a routier, a brigand.

Was I?

It hurt, and troubled my sleep, as well. But in the end, they sold us their grain. The next day we were moving before dawn, heading south around Parma and looking to seize the bridges over the Taro.

Somewhere to the east in the dawn, a German captain was determined to stop me. But he’d never fought the Turks, and his pickets weren’t aggressive, and before the winter fog burned off, I knew from Christopher that the southernmost of the three bridges was the lightest held. He had two dozen barbutes, or German lances, holding the southern bridge. A pair of low-born pickets shivered in the winter mist, and the rest were mounted in front of the bridge.

Sam Bibbo rode up with forty of my archers, dismounted, and cleared them in a minute. He didn’t kill a man, although there were two dead horses on the bridge, but the Germans ran. Mercenaries can’t afford to lose horses.

The second they turned their backs, we were moving across, spreading north, cutting the little garrisons at t

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...