- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Political alliances are beginning to rupture. No state is immune: England, France, the Holy Roman Empire, Milan, Genoa, Venice, Constantinople . . . Every mercenary knight for hundreds of miles must sharpen his sword and prepare for battle.

But Sir William Gold has other problems. Just to reach Europe, he must capture its most unassailable fortress. He must also protect his liege-lord, the Green Count, from assassins hell-bent on his demise.

The balance of power in the West will change. William Gold must trust to hope, and his men, that he lands on the winning side . . .

Release date: June 18, 2019

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

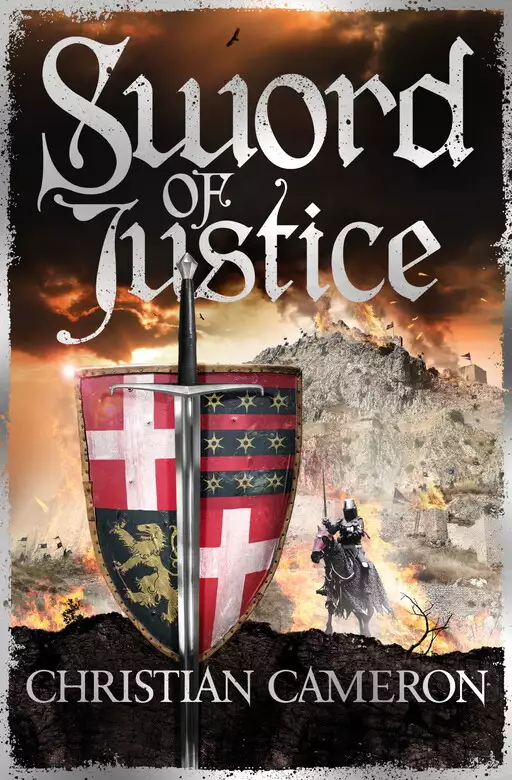

Sword of Justice

Christian Cameron

Arming sword – A single-handed sword, thirty inches or so long, with a simple cross guard and a heavy pommel, usually double-edged and pointed.

Arming coat – A doublet either stuffed, padded, or cut from multiple layers of linen or canvas to be worn under armour.

Alderman – One of the officers or magistrates of a town or commune.

Aventail – The cape of maille, or in some cases textile, that was suspended from a basinet or great helm to protect against rising blows to the neck. Attached by means of vervelles and laced on.

Bailli – A French royal officer much like an English sheriff; or the commander of a ‘langue’ in the Knights of Saint John.

Baselard – A dagger with a hilt like a capital I, with a broad cross both under and over the hand. Possibly the predecessor of the rondel dagger, it was a sort of symbol of chivalric status in the late fourteenth century. Some of them look so much like Etruscan weapons of the bronze and early iron age that I wonder about influences . . .

Basinet – A form of helmet that evolved during the late middle ages, the basinet was a helmet that came down to the nape of the neck everywhere but over the face, which was left unprotected. It was almost always worn with an aventail made of maille, which fell from the helmet like a short cloak over the shoulders. By 1350, the basinet had begun to develop a moveable visor, although it was some time before the technology was perfected and made able to lock.

Brigands – A period term for foot soldiers that has made it into our lexicon as a form of bandit.

Burgher – A member of the town council, or sometimes, just a prosperous townsman.

Commune – In the period, powerful towns and cities were called communes and had the power of a great feudal lord over their own people, and over trade.

Coat of plates – In the period, the plate armour breast and back plate were just beginning to appear on European battlefields by the time of Poitiers – mostly due to advances in metallurgy which allowed larger chunks of steel to be produced in furnaces. Because large pieces of steel were comparatively rare at the beginning of William Gold’s career, most soldiers wore a coat of small plates – varying from a breastplate made of six or seven carefully formed plates, to a jacket made up of hundreds of very small plates riveted to a leather or linen canvas backing. The protection offered was superb, but the garment is heavy and the junctions of the plates were not resistant to a strong thrust, which had a major impact on the sword styles of the day.

Corazina – A coat of plates, often covered in cloth, especially velvet. The difference between a common soldier’s coat of plates and a corazina is that the plates in the corazina are more carefully formed in three dimensions to provide a much better fit and better protection. The corazina is better in many ways to solid plate: it moves with the wearer. However, it is only as durable as its weakest part, the cloth covering, which wears quickly.

Cote – In the novel, I use the period term cote to describe what might then have been called a gown – a man’s overgarment worn atop shirt and doublet or pourpoint or jupon, sometimes furred, fitting tightly across the shoulders and then dropping away like a large bell. They could go all the way to the floor with buttons all the way, or only to the middle of the thigh. They were sometimes worn with fur, and were warm and practical.

Demesne – The central holdings of a lord – his actual lands, as opposed to lands to which he may have political rights but not taxation rights or where he does not control the peasantry.

Donjon – The word from which we get dungeon.

Doublet – A small garment worn over the shirt, very much like a modern vest, that held up the hose and to which armour was sometimes attached. Almost every man would have one. Name comes from the requirement of the Paris Tailor’s Guild that the doublet be made – at the very least – of a piece of linen doubled – thus, heavy enough to hold the grommets and thus to hold the strain of the laced-on hose.

Gauntlets – Covering for the hands was essential for combat. Men wore maille or scale gauntlets or even very heavy leather gloves, but by William Gold’s time, the richest men wore articulated steel gauntlets with fingers.

Gown – An overgarment worn in Northern Europe (at least) over the kirtle, it might have dagged or magnificently pointed sleeves and a very high collar and could be worn belted, or open to daringly reveal the kirtle, or simply, to be warm. Sometimes lined in fur, often made of wool.

Haubergeon – Derived from hauberk, the haubergeon is a small, comparatively light maille shirt. It does not go down past the thighs, nor does it usually have long sleeves, and may sometimes have had leather reinforcement at the hems.

Helm or haum – The great helm had become smaller and slimmer since the thirteenth century, but continued to be very popular, especially in Italy, where a full helm that covered the face and head was part of most harnesses until the armet took over in the early fifteenth century. Edward III and the Black Prince both seem to have worn helms. Late in the period, helms began to have moveable visors like basinets.

Hobilar – A non-knightly man-at-arms in England.

Horses – Horses were a mainstay of medieval society, and they were expensive, even the worst of them. A good horse cost many days’ wages for a poor man; a warhorse cost almost a year’s income for a knight, and the loss of a warhorse was so serious that most mercenary companies specified in their contracts (or condottas) that the employer would replace the horse. A second level of horse was the lady’s palfrey – often smaller and finer, but the medieval warhorse was not a giant farm horse, but a solid beast like a modern Hanoverian. Also, ronceys which are generally inferior smaller horses ridden by archers.

Hours – The medieval day was divided – at least in most parts of Europe – by the canonical periods observed in churches and religious houses. Within these divisions, time was relative to sunrise and sunset, so exact times varied with the seasons. The day started with Prime very early, around 6 a.m., ran through Terce at mid-morning to Sext in the middle of the day, and came around Nones at mid-afternoon to Vespers towards evening. This is a vast simplification, but I have tried to keep to the flavour of medieval time by avoiding minutes and seconds. They basically weren’t even thought of until the late sixteenth century.

Jupon – A close-fitting garment, in this period often laced, and sometimes used to support other garments. As far as I can tell, the term is almost interchangeable with doublet and with pourpoint. As fashion moved from loose garments based on simply cut squares and rectangles to the skintight, fitted clothes of the mid-to-late fourteenth century, it became necessary for men to lace their hose (stockings) to their upper garment – to hold them up! The simplest doublet (the term comes from the guild requirement that they be made of two thicknesses of linen or more, thus ‘doubled’) was a skintight vest worn over a shirt, with lacing holes for ‘points’ that tied up the hose. The pourpoint (literally, For Points) started as the same garment. The pourpoint became quite elaborate, as you can see by looking at the original that belonged to Charles of Blois online. A jupon could also be worn as a padded garment to support armour (still with lacing holes, to which armour attaches) or even over armour, as a tight-fitting garment over the breastplate or coat of plates, sometimes bearing the owner’s arms.

Kirtle – A women’s equivalent of the doublet or pourpoint. In Italy, young women might wear one daringly as an outer garment. It is skin tight from neck to hips, and then falls into a skirt. Fancy ones were buttoned or laced from the navel. Moralists decried them.

Langue – One of the sub-organisations of the Order of the Knights of Saint John, commonly called the Hospitallers. The langues did not always make sense, as they crossed the growing national bounds of Europe, so that, for example, Scots knights were in the English Langue, Catalans in the Spanish Langue. But it allowed men to eat and drink with others who spoke the same tongue, or nearer to it. To the best of my understanding, however, every man, however lowly, and every serving man and woman, had to know Latin, which seems to have been the Order’s lingua franca. That’s more a guess than something I know.

Leman – A lover.

Longsword – One of the period’s most important military innovations, a double-edged sword almost forty-five inches long, with a sharp, armour-piercing point and a simple cross guard and heavy pommel. The cross guard and pommel could be swung like an axe, holding the blade – some men only sharpened the last foot or so for cutting. But the main use was the point of the weapon, which, with skill, could puncture maille or even coats-of-plates.

Maille – I use the somewhat period term maille to avoid confusion. I mean what most people call chain mail or ring mail. The manufacturing process was very labour-intensive, as real mail has to have each link either welded closed or riveted. A fully armoured man-at-arms would have a haubergeon and aventail of maille. Riveted maille was almost proof against the cutting power of most weapons – although concussive damage could still occur! And even the most strongly made maille is ineffective against powerful archery, spears, or well-thrust swords in the period.

Malle – Easy to confuse with maille, malle is a word found in Chaucer and other sources for a leather bag worn across the back of a horse’s saddle – possibly like a round-ended portmanteau, as we see these for hundreds of years in English art. Any person travelling, be he or she pilgrim or soldier or monk, needed a way to carry clothing and other necessities. Like a piece of luggage, for horse travel.

Partisan – A spear or light glaive, for thrusting but with the ability to cut. My favourite, and Fiore’s, was one with heavy side-lugs like spikes, called in Italian a ghiavarina. There’s quite a pretty video on YouTube of me demonstrating this weapon . . .

Paternoster (sometimes Pater Noster) – A set of beads, often with a tassel at one end and a cross at the other – much like a modern rosary, but usually straight rather than in a circle. The use of prayer beads was introduced to Christianity in the twelfth or thirteenth centuries, from Islam and further east.

Pauldron or Spaulder – Shoulder armour.

Pourpoint – a somewhat generic word in the time of William Gold. In the fourteenth century, the garment’s name refers to the piercing of the fabric during the quilting process. Raw cotton was most frequently used as the ‘filler.’ Pourpoint does not, in fact, refer to the act of pointing one’s chausses or leg armour to the garment. According to Le Pelerinage de la Humaine (1331), ‘Because the gambeson is made with many prickings (stitches), that is why it is also called a pourpoint. It is understood that a gambeson with many prickings is worth a lot, and one without these prickings is worth nothing.’ (With thanks to Tasha Dandelion Kelly at cottesimple.com)

Prickers – Outriders and scouts.

Rondel Dagger – A dagger designed with flat round plates of iron or brass (rondels) as the guard and the pommel, so that, when used by a man wearing a gauntlet, the rondels close the space around the fingers and make the hand invulnerable. By the late fourteenth century, it was not just a murderous weapon for prying a knight out of plate armour, it was a status symbol – perhaps because it is such a very useless knife for anything like cutting string or eating . . .

Sabatons – The ‘steel shoes’ worn by a man-at-arms in full harness, or full armour. They were articulated, something like a lobster tail, and allow a full range of foot movement. They are also very light, as no fighter would expect a heavy, aimed blow at his feet. They also helped a knight avoid foot injury in a close press of mounted mêlée – merely from other horses and other mounted men crushing against him.

Sele – Happiness or fortune. The sele of the day is the saint’s blessing.

Stradiote – A Greek or Albanian cavalryman. By the late fourteenth century, Greek cavalry probably resembled Turkish cavalry; certainly by the mid-fifteenth century they were expert scouts and were practicing horse-archery. In maille or scale armour, if contemporary saint’s icons can be used as evidence.

Shift – A woman’s innermost layer, like a tight-fitting linen shirt at least down to the knees, worn under the kirtle. Women had support garments, like bras, as well.

Tow – The second stage of turning flax into linen, tow is a fibrous, dry mass that can be used in most of the ways we now use paper towels, rags – and toilet paper. Biodegradable, as well.

Villein – A serf or unfree agricultural worker.

Vedette – A cavalry scout or guard on watch.

Yeoman – A prosperous countryman. Yeoman families had the wealth to make their sons knights or squires in some cases, but most yeoman’s sons served as archers, and their prosperity and leisure time to practise gave rise to the dreaded English archery. Only a modestly well-to-do family could afford a six-foot yew bow, forty or so cloth yard shafts with steel heads, as well as a haubergeon, a sword, and helmet and perhaps even a couple of horses – all required for military service.

Prologue

Calais, June 1381

William Gold, knight and Captain of Venice, came down the stairs early in a plain brown cote-hardie that looked to be twenty years out of date. He paused at the common room barre and took an apple from the pewter dish that sat there, and rubbed it on his cote-hardie like an apprentice. The pot-boy, busy polishing the counter with walnut oil, nonetheless managed a full bow, as if Sir William was the King of England.

‘What’s your name, lad?’ Gold asked after two bites of his apple.

‘Which it is, William, my lord.’ The boy flushed a very unbecoming bright red that showed all the pimples on his acne-scarred young face as almost white.

Gold smiled. ‘I’m not much of a lord, young William.’ He ate the rest of the apple in six bites, and then he ate the core as well. ‘How d’ye come to be a pot-boy, then? You look hale.’

‘He is a distant cousin’s second son,’ the keeper said, emerging from behind his writing table, rubbing his eyes and wondering if Sir William had been sent to encourage early rising. ‘It is a long story.’

Gold smiled at William. ‘Can you pull a bow?’ he asked.

The innkeeper frowned. ‘Now, see here, good sir knight. My cousin will think I have done him no favour—’

‘I’m naw the best,’ the boy said, cutting across the publican, ‘but I can pull me da’s bow to the mouth.’

‘How many times in a minute?’ Gold asked.

‘My lord, I can show you,’ the boy said. He had a broad back and long arms. He turned and dashed for the family stairs in the yard.

‘Sir William,’ the innkeeper pressed, as soon as the lad was gone.

The red-haired knight turned and met the innkeeper’s gaze. His face wore what the innkeeper’s wife would have called a ‘man-of-business’ look. ‘What do ye pay him?’ Gold asked.

‘Sir knight, there is no question of payment. I have taken him to raise him to—’

‘No wage? Just keep?’ Gold said. His voice was light. ‘Listen, messire. If I take him, he’ll either make his fortune or be dead. It’s his choice. Saint Augustine and Aquinas are in agreement about free will, eh?’

‘I take it unkindly—’ The innkeeper tried to protest.

‘That’s too bad,’ Gold interrupted. ‘I never seek to anger any man. But that boy is wasted here, and I challenge ye: you know it yourself.’

Young William reappeared with a bow. It was long – almost as long as Sir William. It showed evidence of both green and white paint, and its belly was as thick as a lady’s wrist.

‘You are from Cheshire, then?’ Gold asked.

The boy flushed. ‘Which me da’ was,’ he said.

‘Your da’ served the king. Crécy?’ Gold asked, with an eye to the paint.

‘Aye, my lord.’ The boy strung the war bow with difficulty.

Gold took it from him. ‘This bow was once a mighty warrior,’ he said. ‘But, like me, it has some marks of age, and I misdoubt it has anything like the pull of youth.’ He pointed it at the floor and then raised it, swiftly, like a hawk rising to a lure, and Aemilie, the keeper’s daughter, just emerging from the family stairs, stood transfixed as the bow centred on her …

Sir William let the tension off the bow gradually. ‘Not so bad, after all. A master made this, sure enough, but it cannot go to war again. Still, show me your draw. And, demoiselle, pardon me for affrighting you.’

‘Sir knight, it would take more than an empty bow to affright me,’ she said.

The innkeeper winced to hear her tone. In the eyes of a father, there was no man in God’s creation more unsuitable for his daughter’s adolescent affection than the red-haired knight.

But she smiled warmly at young William. ‘Let’s see you pull it,’ she said. ‘Go and show Sir William, now, Bill. I know ye can.’

Out in the yard, the boy carefully positioned his feet. Sir William had a second apple, but after a bite, he grinned. ‘There’s nothing to put strength in a man like the smile of a beautiful woman,’ he said.

Young William caught his smile and managed to relax a little. Gold saw him clear his head of rubbish, saw him give a little shake with his shoulders, and then the great bow went down like a diving swallow and then up, high in the air. The boy’s shoulders quivered, but the string came all the way back.

‘One,’ Gold said.

The boy let the tension off and took two deep breaths, and then, almost as swift as the swallow he imitated, the bow went down again. The muscles across his shoulder blades stiffened, and the bow came up.

‘Two,’ Gold said.

One of Gold’s archers came out – a swarthy man with an odd face, narrow eyes and skin like crackled parchment. He stood close by Gold.

The boy thought the archer looked like a demon from Hell. He tried to quell his pulse; he’d never managed more than three pulls in succession.

He breathed out, and began …

‘Three,’ Gold said.

‘Not fucking bad, by Jesus,’ said the demon, who ducked his head as he said the name Jesus.

‘John, when you bow your head at the name of Jesus, which, may I add, you are using blasphemously,’ Gold said, ‘it makes no sense.’

‘Every fucking sense,’ John the Turk said. ‘Eh, boy. Don’t stop for me.’ The swarthy man looked back at the knight. ‘Jesus,’ he bowed his head, ‘is God. Yes?’

‘Yes, John.’ Gold sounded weary. The boy’s bow went down, trembled a little at the fetch, and then rose again, an avenging angel.

‘Four,’ Gold said. ‘Give me one more, lad.’

‘Well trained, boy,’ John grunted. ‘So I swear by God, and I bow my— Jesu! Damnatione!’ John spat.

The bow had exploded with a sharp crack.

The boy, despite his august audience, fell on his knees, the pieces of his father’s bow across his lap, ignoring the blood that the whiplash of the bowstring had drawn from his bow hand.

Gold looked back. Aemilie and her father were both standing in the great mullioned window that was the hallmark of the inn, the best in Calais. Master Chaucer was leaning in the doorway.

Shaking his head at the Tartar’s blasphemy, Gold approached the boy.

‘I’m sorry it broke,’ Gold said, putting his hand on the boy’s shoulder. ‘But you have the makings of an archer, eh, John?’

John nodded. ‘Take him.’ He turned without bowing and went back towards the barn.

‘Why not leave him and let him live?’ Chaucer called from the doorway, a little too loudly.

‘Oh, master, I want to go!’ Young William was fighting tears. His father’s bow had been his most prized possession.

‘You are too young to know anything,’ Chaucer muttered, approaching the pair. The small, wiry man stood very close to Sir William, who was a head taller. ‘Let him go, William. Your tales go to his head. He’ll just die, face down in the mud somewhere. Or the plague will take him, or dysentery, torture, raped by captors, gutted like a fish, puking blood …’

Gold shrugged. ‘You would know,’ he said mildly. ‘And yet he might ride back here in ten years in a coat of plates, riding a tall horse with a squire and a full purse.’

‘A killer,’ Chaucer said bitterly.

‘There’s more to the life of arms than killing, Master Chaucer,’ Gold said.

‘Aye, I can hear the same poem from a Southwark strumpet, who’ll tell me she brings comfort and love to loveless men, when all she does is fuck them,’ Chaucer spat.

Gold’s face turned a bright crimson, and then returned to its normal shade. ‘You are hard on your fellow men, Geoffrey,’ he said. ‘But then, you are hard on yourself. Let the boy decide for himself.’

‘He can no more decide for himself than he could choose chastity if …’ Chaucer caught himself, but his glance at Aemilie revealed the pattern of his thought; the girl flushed, and her father put a hand to his dagger.

Gold shocked them all by passing his arm around Chaucer and locking him in an embrace. ‘I hear ye,’ he said. ‘We’ll leave this for the morn. I’m off to prayers.’

‘I’ll come,’ Chaucer said.

The two men walked off in what appeared perfect amity, leaving a boy and a broken bow in the yard.

John the Turk appeared with a new, white yew bow, almost as tall as Sir William himself, and its belly thicker than Aemilie’s wrists. ‘Spanish,’ the Kipchak said, running a hand down the smooth wood. ‘The best. For you.’

‘Sweet Virgin, I cannot afford such,’ young William said.

John the Turk knew a great deal about bows, but more about young men. He nodded gravely. ‘You broke good bow in service of company,’ he said. ‘We replace it, eh? We have a bundle of sixty.’

‘Sixty?’ the boy asked, stupefied at such riches.

The Kipchak shrugged. ‘And another sixty in Italy. War is bad for bows.’

He grinned his odd grin and went back towards the barn.

Aemilie glanced at her father. ‘I don’t understand them,’ she said.

‘The one who looks like the Devil?’ the keeper asked.

‘Nay, Pater. The knight and Master Chaucer.’ She looked after the two men.

Her father was watching the strange man with the slanted eyes walking away from them. ‘I don’t really, either,’ he said. ‘But I’m going to wager that when men spend enough time together, and experience enough … even if they mislike each other, in time … they are like brothers. My brother and I used to fight like that.’

‘I like him, Pater,’ she said. ‘But I’m not going to play the fool.’

He ruffled her hair. ‘He’s a fine man,’ the innkeeper admitted. ‘But also the Devil incarnate.’

‘Oh,’ she said. ‘By the Virgin, Pater, do ye think I don’t know?’ She shook her head and went to find her mother.

The rain started before Matins were over, and came down like Noah’s flood, and even Sir William, usually so debonair, looked like a drowned cat and smelled like wet wool when he returned from church. Master Froissart, late from his bed, was drinking small beer in the common room. When the damp men had changed into dry garments and the fire had been touched up, Sir William took a chair by the chimney and drank off a huge jack of hot porter.

‘Ah,’ he sighed. ‘England. Italy has nothing like that.’ He wiped his beard.

‘Passports?’ Froissart asked.

Gold looked over the common room. A dozen of his men-at-arms and most of the archers were packed in the low room, as well as several off-duty servants and some local Englishmen – a shoemaker and a cutler. Gold shrugged.

‘I suppose now is as good a time to say it as any,’ he said. ‘There’s trouble in England, gentles. They say the commons have risen against the lords, and that there’s been a lot of killing.’ Gold looked over the room, and then at Chaucer. ‘They say Sir Robert Hales is dead, murdered by the crowd.’

‘Christ,’ Chaucer said.

‘Aye, and I will pray for his soul. He was a good knight, whatever his sins.’ Gold looked into the fire. ‘He was with us at Alexandria …’ He shook his head. ‘Any road, gentles, the way of it is this: the castle is holding our passports until such time as they have a ship out of the Thames or the south ports that gives them cause to hope.’

‘That could be weeks,’ Froissart said.

‘Aye,’ Gold said. ‘And all my profits wasted on good living in a fine inn.’ He raised an eyebrow at the keeper. ‘If it hasn’t resolved itself in a week or two, I’ll be headed back to Venice.’

‘More stories!’ called a voice.

Chaucer laughed. ‘I think you have a willing audience,’ he said, and then more soberly: ‘The Italian wedding?’

Gold looked at Froissart. ‘It’s not just my story, although I know an ending that mayhap you do not. But you were both there; you’ll interrupt me constantly and insist that I tell the truth.’

Chaucer laughed. ‘You really should have been a scribbler, like me,’ he snorted.

Froissart leaned back. ‘I would like to understand what I saw in Milan,’ he said. ‘I still … It was beautiful, yes? And terrible?’

‘Aye,’ Gold said. ‘So it was. The worst year of my life, in many ways. But the year before it was wonderful.’

‘Made your reputation,’ Chaucer said.

‘Perhaps,’ Gold said.

At the far end of the room, young William the pot-boy had just slipped into a corner, eyes bright with expectation. Sir William reached behind him, hiding a smile of satisfaction, and his squire handed him a well-thumbed book of hours. The knight laid it on the table. Chaucer leaned over, flipped a page, and exclaimed, ‘You are a scribbler!’

Sir William smiled. ‘It started one afternoon in Venice; I was copying itineraries, the year I served the Green Count. Look, it’s not much; just the weather, usually.’

‘And the saints’ days,’ Froissart said. ‘And these little crosses. What are they?’

‘Men I killed,’ Gold said. ‘I pray for them. I like to remember who they were.’

There I was with an arming sword in my hand, and I was desperately outmatched. A trickle of blood running down my right bicep, my old arming coat cut through all eight layers of linen, and sweat blinding my eyes.

I made a bad, hasty parry, but at least I wasn’t deceived by my opponent’s devilish deception. From the cross, I pushed, eager to use my size and strength against the little bastard, but he was away like a greased pig. He evaded my winding cut at the face with a wriggle and we were both past, turning, swords back into gardes; he in the boar’s tooth and me with my sword high …

He raised his sword, a clear provocation, given he was so damnably fast.

I shook my head to clear the sweat. Backed a step in unfeigned fear.

He glided forward, perfectly controlled. I dropped my sword hesitantly into a point forward garde; I couldn’t allow his point so close to my heart …

And then, out of my hesitation, I attacked. My wrist moved; my blade struck his a sharp blow. And I snapped the blade up into a high thrust, right at his face.

He had to parry. And he had to parry high.

I rolled my right wrist off that parry, rotating my heavy arming sword through almost a full circle, from the high cross all the way around, my thumb flat against the blade for control, and my blade just barely outraced his desperate parry to tag him under the arm, where no one has a good defence.

He burst into peals of laughter, spun away with my sword tucked under his arm, and sprawled to the ground in a pantomime of death. My son Edouard flung himself on the prostrate Fiore and pretended to shower him with dagger blows.

Fiore was laughing. ‘I just taught you that!’ he roared.

And he had. Just the day before.

It was a glorious spring of training, and we were all on the island of Lesvos, in Outremer. In the year of Our Lord 1367, I had reached the end of my desire to go on crusade. I’d be too strong to say I was sick of the whole thing; that came later. But I doubted the very basis of the idea. It was clear to me that the Infidel were neither so very bad nor so easy to convert. I had, I fear, spent too much time with Sabraham; I began to see the wisdom in the Venetians and the Genoese, who traded with them every day and seemed to know a great deal more about the Infidel than anyone in Avignon or Rome or Paris.

Spring in Outremer is as magnificent as spring in England. Lesvos is the most beautiful of the Greek islands, with magnificent contrasts: steep, waterless valleys like the Holy Land, which is close enough, for all love; and then lush greenery and magnificent fields of flowers; hillsides like a Venetian miniature; roses. Gracious God, it was beautiful. And as Emile recovered from pregnancy, having given us Cressida, we wandered the fields of my new lordship, and we were like sweethearts. The only cloud in the sky was that Sir Miles Stapleton, one of my closest companions, was recalled to England to marry and take up his uncle’s lands. His uncle of the same name had been killed at Auray, in ’64. We threw him an excellent revel; before he left, we all wrote letters and I sent Hawkwood a long one, as well as another for Messire P

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...