- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

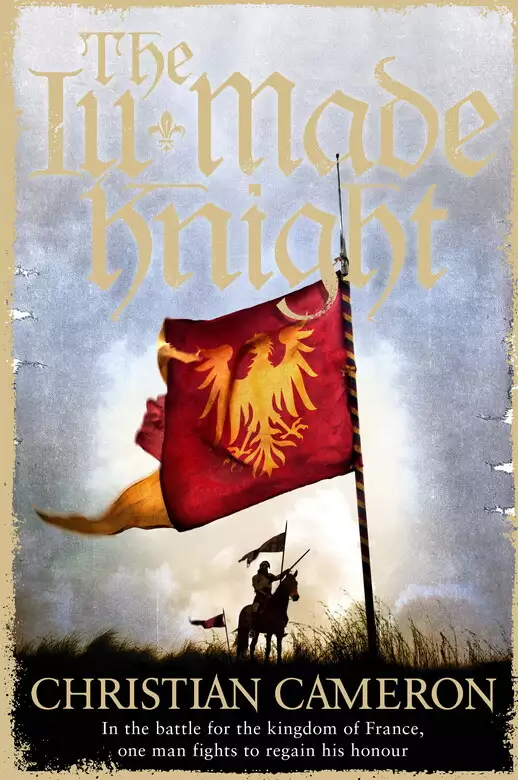

September, 1356. Poitiers. The greatest knights of the age were ready to give battle. On the English side, Edward, the Black Prince, who'd earned his spurs at Crecy. On the French side, the King and his son, the Dauphin. With 12,000 knights. And then there is William Gold. A cook's boy, who had once been branded as a thief. William dreams of being a knight, but in this savage new world of intrigue, betrayal and greed, first he must learn to survive. As rapacious English mercenaries plunder a country already ravaged by plague, and the peasantry take violent revenge against the French knights who have failed to protect them, is chivalry any more than a boyish fantasy?

Release date: August 1, 2013

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Ill-Made Knight

Christian Cameron

Arming sword – A single-handed sword, thirty inches or so long, with a simple cross guard and a heavy pommel, usually double-edged and pointed.

Arming coat – A doublet either stuffed, padded, or cut from multiple layers of linen or canvas to be worn under armour.

Alderman – One of the officers or magistrates of a town or commune.

Basinet – A form of helmet that evolved during the late middle ages, the basinet was a helmet that came down to the nape of the neck everywhere but over the face, which was left unprotected. It was almost always worn with an aventail made of maille, which fell from the helmet like a short cloak over the shoulders. By 1350, the basinet had begun to develop a moveable visor, although it was some time before the technology was perfected and made able to lock.

Brigands – A period term for foot soldiers that has made it into our lexicon as a form of bandit – brigands.

Burgher – A member of the town council, or sometimes, just a prosperous townsman.

Commune – In the period, powerful towns and cities were called communes and had the power of a great feudal lord over their own people, and over trade.

Coat of plates – In period, the plate armour breast and back plate were just beginning to appear on European battlefields by the time of Poitiers – mostly due to advances in metallurgy which allowed larger chunks of steel to be produced in furnaces. Because large pieces of steel were comparatively rare at the beginning of William Gold’s career, most soldiers wore a coat of small plates – varying from a breastplate made of six or seven carefully formed plates, to a jacket made up of hundreds of very small plates riveted to a leather or linen canvas backing. The protection offered was superb, but the garment was heavy and the junctions of the plates were not resistant to a strong thrust, which had a major impact on the sword styles of the day.

Cote – In the novel I use the period term cote to describe what might then have been called a gown – a man’s over-garment worn atop shirt and doublet or pourpoint or jupon, sometimes furred, fitting tightly across the shoulders and then dropping away like a large bell. They could go all the way to the floor with buttons all the way, or only to the middle of the thigh. They were sometimes worn with fur, and were warm and practical.

Demesne – The central holdings of a lord – his actual lands, as opposed to lands to which he may have political rights but not taxation rights or where he does not control the peasantry.

Donjon – The word from which we get dungeon.

Doublet – A small garment worn over the shirt, very much like a modern vest, that held up the hose and sometimes to which armour was attached. Almost every man would have one. Name comes from the requirement of the Paris Tailors’ guild that the doublet be made – at the very least – of a piece of linen doubled, thus heavy enough to hold the grommets and hold the strain of the laced-on hose.

Gauntlets – Covering for the hands was essential for combat. Men wore maille or scale gauntlets or even very heavy leather gloves, but by William Gold’s time, the richest men wore articulated steel gauntlets with fingers.

Gown – An over-garment worn in Northern Europe (at least) over the kirtle, it might have dagged or magnificently pointed sleeves and a very high collar and could be worn belted to be warm, or open, to daringly reveal the kirtle. Sometimes lined in fur, often made of wool.

Haubergeon – Derived from hauberk, the haubergeon is a small, comparatively light maille shirt. It does not go down past the thighs, nor does it usually have long sleeves, and may sometimes have had leather reinforcement at the hems.

Helm or haum – The great helm had become smaller and slimmer since the thirteenth century, but continued to be very popular, especially in Italy, where a full helm that covered the face and head was part of most harnesses until the armet took over in the early fifteenth century. Edward III and the Black Prince both seem to have worn helms. Late in the period, helms began to have moveable visors like basinets.

Hobilar – A non-knightly man-at-arms in England.

Horses – Horses were a mainstay of medieval society, and they were expensive, even the worst of them. A good horse cost many days wages for a poor man; a war horse cost almost a year’s income for a knight, and the loss of a warhorse was so serious that most mercenary companies specified in their contracts (or condottas) that the employer would replace the horse. A second level of horse was the lady’s palfrey – often smaller and finer, but the medieval warhorse was not a giant farm horse, but a solid beast like a modern Hanoverian. Also, ronceys, which are generally inferior, smaller horses ridden by archers.

Hours – The medieval day was divided – at least in most parts of Europe – by the canonical periods observed in churches and religious houses. The day started with matins very early, past nonnes in the middle of the day, and came around to vespers towards evening. This is a vast simplification, but I have tried to keep to the flavor of medieval time by avoiding minutes and seconds.

Jupon – A close-fitting garment, in this period often laced, and sometimes used to support other garments. As far as I can tell, the term is almost interchangeable with doublet and with pourpoint. As fashion moved from loose garments based on simply cut squares and rectangles to the skintight, fitted clothes of the mid-to-late 14th century, it became necessary for men to lace their hose (stockings) to their upper garment – to hold them up! The simplest doublet (the term comes from the guild requirement that they be made of two thicknesses of linen or more, ‘doubled’) was a skin-tight vest worn over a shirt, with lacing holes for ‘points’ that tied up the hose. The pourpoint (literally, For Points) started as the same garment. The pourpoint became quite elaborate, as you can see by looking at the original that belonged to Charles of Blois online. A jupon could also be worn as a padded garment to support armour (still with lacing holes, to which armour attach) or even over armour, as a tight-fitting garment over the breastplate or coat of plates, sometimes bearing the owner’s arms.

Kirtle – A women’s equivalent of the doublet or pourpoint. In Italy, young women might wear one daringly as an outer garment. It is skintight from neck to hips, and then falls into a skirt. Fancy ones were buttoned or laced from the navel. Moralists decried them.

Leman – A lover.

Longsword – One of the period’s most important military innovations, a double-edged sword almost forty-five inches long, with a sharp, armour-piercing point and a simple cross guard and heavy pommel. The cross guard and pommel could be swung like an axe, holding the blade – some men only sharpened the last foot or so for cutting. But the main use was the point of the weapon which, with skill, could puncture maille or even coats of plates.

Maille – I use the somewhat period term maille to avoid confusion. I mean what most people call chain mail or ring mail. The manufacturing process was very labor intensive, as real mail has to have each ling either welded closed or riveted. A fully armoured man-at-arms would have a haubergeon and aventail of maille. Riveted maille was almost proof against the cutting power of most weapons – although concussive damage could still occur! And even the most strongly made maille is ineffective against powerful archery, spears, or well-thrust swords in period.

Malle – Easy to confuse with maille, malle is a word found in Chaucer and other sources for a leather bag worn across the back of a horse’s saddle – possibly like a round-ended portmanteau, as we see these for hundreds of years in English art. Any person travelling, be he or she pilgrim or soldier or monk, needed a way to carry clothing and other necessities. Like a piece of luggage, for horse travel.

Partisan – A spear or light glaive, for thrusting but with the ability to cut.

Pater Noster – A set of beads, often with a tassle at one end and a cross at the other – much like a modern rosary, but straight rather than in a circle.

Pauldron or Spaulder – Shoulder armour.

Prickers – Outriders and scouts.

Rondel Dagger – A dagger designed with flat, round plates of iron or brass (rondels) as the guard and the pommel, so that, when used by a man wearing a gauntlet, the rondels close the space around the fingers and make the hand invulnerable. By the late 14th century, it was not just a murderous weapon for prying a knight out of plate armour, it was a status symbol – perhaps because it is such a very useless knife for anything like cutting string or eating …

Sabatons – The ‘steel shoes’ worn by a man-at-arms in full harness, or full armour. They were articulated, something like a lobster tail, and allowed a full range of foot movement. They are also very light, as no fighter would expect a heavy, aimed blow at his feet. They also helped a knight avoid foot injury in a close press of mounted mêlée – merely from other horses and other mounted men crushing against him.

Shift – A woman’s innermost layer, like a tight-fitting linen shirt at least down to the knees, worn under the kirtle. Women had support garments, like bras, as well.

Tow – The second stage of turning flax into linen, tow is a fibrous, dry mass that can be used in most of the ways we now use paper towels, rags and toilet paper. Biodegradable, as well.

Yeoman – A prosperous countryman. Yeoman families had the wealth to make their sons knights or squires in some cases, but most yeoman’s sons served as archers, and their prosperity and leisure time to practice gave rise to the dreaded English archery. Only a modestly well-to-do family could afford a six-foot yew bow, forty or so cloth yard shafts with steel heads, as well as a haubergeon, a sword, helmet and perhaps even a couple of horses; all required for military service.

Prologue

Calais, June, 1381

The sound of iron-shod hooves rang on the cobbles of the gatehouse road like the sound of weapons hitting armour. As the cavalcade passed into the gatehouse with the arms of England in painted and gilded stone, the soldiers on the gate stood still, and the gate captain bowed deeply as the lord passed at the head of his retinue. He was dressed entirely in red and black; his badge, a spur rowel, repeated endlessly on his velvet gown, his swordbelt, his cloak and his horse’s magnificent red, black and gold barding, all of which was cloth covered, though it could not conceal the small fortune in plate armour he wore. By his side rode his squire, equally resplendent in red, black and gold, carrying his knight’s helmet and lance. Behind them rode a dozen professional men-at-arms, in full harness, their new Italian steel armour gleaming despite a cold, rainy day on the outskirts of Bruges. Behind the men-at-arms rode another dozen English archers who wore almost as much armour as the men-at-arms, and behind them rode another dozen pages. Then came four wagons, and behind the wagons rode servants, also armed. Every man in the column wore the red and black; every man had a gold spur rowel badge on his cloak.

The knight of the spur rowels returned the salute of the gate captain, raising a small wooden baton to his forehead and bowing slightly in the saddle. He smiled, which in return coaxed a smile from the scarred face of the gate captain.

He reined in. ‘John,’ he said. ‘The captain will want to see our letters of passage and our passes.’

His squire handed the helmet and lance to a page and reached into his belt pouch.

The gate captain bowed. ‘My lord. All of us know the arms of Sir William Gold.’ He accepted the papers. ‘The Duke of Burgundy informed us you were en route.’

Sir William Gold made an odd facial movement – half a smile, with only the left side of his mouth moving. ‘How kind of him,’ he said. ‘I’d be wary of forty armed men on my roads, too.’ He leaned down from the saddle. ‘You’re English.’

‘Yes, my lord,’ the man said.

‘I know you. Giles something. Something Giles.’ Sir William took the hood hat from his head and shook the rain off it.

The man’s smile became broader. ‘Anselm Saint-Gilles, my lord.’

‘You were with – damn it, I’m an old man, Saint-Gilles – Brignais. You were at Brignais, with—’

‘Nay, my lord, but I wish I had been. I was Sir Robert Knolly’s man.’ He was obviously pleased to have been recognized. ‘I was an archer, then.’

‘And now a man-at-arms – well done, Saint-Gilles.’ Sir William reached down and offered his hand to clasp, and the gate captain took it.

‘Tell an old war-horse where the best wine is? I don’t know Calais, and I’ve a four-day wait for a ship to England.’ Sir William’s eyes seemed to twinkle.

‘My lord, the White Swan is not the largest inn, but it has the most courteous keeper, the best wine, and it is’ – the man raised his eyebrows expressively – ‘convenient to the baths.’ He bowed again and handed up the leather roll that contained their passports and letters from a dozen kings and independent lords and communes. The Count of Savoy, the Duke of Milan, the Republic of Florence and the Duke of Burgundy were all represented. ‘Please enjoy Calais, my lord,’ he ventured.

‘White Swan – that’s a badge I’ll know. Come and drink a cup of wine with me, Master Saint-Gilles.’ Sir William saluted again with his baton and, without any outward sign, his horse stepped off into the great city.

Behind him, the disciplined men who’d waited silently in the rain while he chatted wiped the rain from their helmets and pressed their mounts into motion.

When they were clear of the gate, the squire leaned forward. ‘My lord?’

‘Speak, John.’

‘We have a letter from the Duke of Lancaster sending us to the White Swan, my lord.’ His tone said, you already knew where we were going. John de Blake was a well-born Englishman of seventeen – an age at which he tried to know everything but understood all too little.

‘It never hurts to ask,’ Sir William said with his odd half-smile. ‘Sometimes, you learn something, John.’

‘Yes, my lord,’ John said.

Forty men do not just dismount and hand over their horses at an inn. Even an inn that is six tall buildings of whitewashed stone surrounding a courtyard that wouldn’t disgrace a great lord’s palace. The courtyard featured a horse fountain and a small garden behind a low wall, with a wrought-iron gate that was gilded and painted. The inn’s doors – twelve of them – were painted a beautiful heraldic blue, and the windows on the courtyard had their frames whitewashed so carefully they seemed to sparkle in the rain, while their glass – very expensive glass too – gave the impression of well-set jewels.

The master of the inn came out into the yard as soon as his gate opened. He bowed, and a swarm of servants fell on his troop like an ambush of friendship.

‘My lord,’ he said in Flemish-English.

Sir William bowed courteously in his saddle. ‘You are the master of the White Swan?’

‘I have that honour. Henri, my lord, at your service. We had word of your coming.’

Sir William’s retinue filled the courtyard. Horses moved and grunted, but the men on their backs were silent and no one made a move to dismount. The servants had moved to take the horses, but hesitated at the armed silence.

‘I pray you, be welcome here,’ the innkeeper said.

Sir William looked back over his troop, his left fist on the rump of his horse. ‘Gentlemen!’ he called out. ‘It seems we’ve fallen soft. Eat and drink your fill. This is a good house, and we’ll do nothing to change its name, eh? Am I understood, gentles?’

There was a chorus of grunts and steel-clad nods. A horse farted, and men smiled.

Sir William sighed and threw an armoured leg over his horse’s broad back. He pressed his breastplate against the red leather of his war saddle and slid neatly to the ground, his golden spurs chiming like the bell for Communion. He handed his war horse’s reins to his page and turned to his squire.

‘There are few places more like heaven on earth for a soldier,’ he said, ‘than a good inn.’

John de Blake allowed himself a nod of agreement.

‘By nightfall, one of our archers will be in Ghent, and another will be so drunk he’ll sell his bow and a third will try and force some girl and get a knife in his gizzard.’ Sir William gave his half-smile.

From the expression on his face, de Blake didn’t think he was supposed to answer that.

‘Other guests?’ Sir William asked of the master of the inn.

‘My lord? I have two gentlemen en route to the convocation in Paris. Monsieur Jean Froissart, and Monsieur Geoffrey Chaucer. On the young King’s business.’

At the name Chaucer, the half-smile appeared.

Innkeepers do not rise in their profession without the ability to read faces. ‘You know Master Chaucer, my lord?’

Sir William Gold’s dark-green eyes looked off into the middle distance. ‘Since we were boys,’ he said. ‘Does he know I am here?’

The innkeeper bowed.

‘Well, then.’ Sir William nodded. ‘Let’s get these men out of the rain, shall we, good master?’

Great lords do not, generally, sit in the common room of inns – even inns that cater to princes. Good inns have rooms and rooms and yet more rooms – they are, in effect, palaces for rent, where lords can hold court, order food and have the use of servants without bringing their own.

Vespers rang, and men went to hear Mass. There was a fine new church across the tiny square from the White Swan, and every man in Gold’s retinue attended. They stood in four disciplined rows and heard the service in English Latin, which made some of his Italians squirm.

After the service, they filled the common room and wine flowed like blood on a stricken battlefield. The near roar of their conversation rose around them to fill the place. Sir William broke with convention and took a small table with his squire and raised a cup to his retinue.

Before the lights were lit, there were dice and cards on most tables.

A voice – pitched a little too harshly, a little too loud, like the voice of a hectoring wife in a farce – came from the stairs: ‘That will be Gold’s little army. If you want to hear the latest from Italy, stop preening and come down!’

Half a smile from Sir William.

He had time to finish his wine. A pretty woman – the only serving woman in the room – appeared with a flagon.

Sir William brushed the greying red hair from his forehead and smiled at her.

Her effort to return his smile was marred by obvious fear. She curtsied. ‘This wine, my lord?’ she asked.

He put a hand on her arm. ‘Ma petite – no one here will touch you. Breathe easy. We’re not fiends from hell, only thirsty Englishmen and a handful of Italians. How many years have you?’

She curtsied again. ‘Sixteen, my lord.’ Despite the hand on her arm, or perhaps because of it, she was as tense as a hunting dog with a scent.

‘And your father asked you to wait on me?’ Sir William asked.

She curtsied a third time.

‘By St John! That is hospitable,’ Sir William said, and his eyes sparkled in a way that made the young woman blush. ‘Listen, ma petite. Serve the wine and don’t linger at table, and no one can reproach you – or grab you. Yes? I served a table or two. A hand reaches for you, you move through it and pretend nothing happened, yes?’

She nodded. ‘This is what my father says.’

‘Wise man. Just so. On your way, ma petite.’ Sir William’s odd green eyes met hers before she could look down.

Later, she told a friend it was like looking into the eyes of a wolf.

The knight got to his feet as she moved away and bowed. ‘Ah, Master Chaucer, the sele of the day to you.’ He offered a hand. ‘You are a long way from London.’

Chaucer had a narrow face and a curling beard that made him look like the statues of Arabs in the cathedrals, or like a sprite or elf, to the old wives. He took the knight’s hand and they exchanged a kiss of peace – carefully.

‘The king’s business,’ Chaucer said. His answering smile could have meant anything.

Sir William nodded. ‘Of course. As always, eh?’ He turned to the other man – a tall, blond man, almost gangly in his height, with golden hair. ‘You are a Hainaulter, unless I miss my guess, monsieur.’

Chaucer indicated his companion. ‘Monsieur de Froissart.’

Sir William offered his hand and Froissart bowed deeply. ‘One is . . . deeply moved to meet so famous a knight.’

Sir William shrugged. ‘Oh, as to that,’ he said.

‘You must know he’s writing a book of all the great deeds of arms of our time,’ Chaucer said.

Froissart bowed again. ‘Master Chaucer is too kind. One makes every attempt to chronicle the valour, the prowess. The . . . chivalry.’

Sir William’s green eyes strayed to Chaucer’s. ‘Not your sort of book at all,’ he said.

Chaucer’s eyes were locked on Sir William’s. ‘No,’ he said. ‘If I wrote such a chronicle, it would not be about valour. Or prowess.’

The two men looked at each other for too long. Long enough for John de Blake to move, worried there might be violence; for Aemilie, the innkeeper’s daughter, dressed in her very best clothes, to flatten herself against the plastered wall, and for Monsieur de Froissart to worry that he had said something out of place. He looked back and forth between the two men.

‘We could sit,’ Sir William said. The room had fallen quiet, but with these words, games of cards and dice sprang back into action and conversations resumed.

‘How have you kept, Geoffrey? When did we last meet? Milan?’ Sir William asked.

‘The wedding of Prince Lionel,’ Chaucer said. ‘No thanks to you.’

Sir William laughed. ‘You have me all wrong, Master Chaucer. I was not against you. The French were against us both.’

Chaucer frowned. ‘Perhaps.’ He collected himself. ‘What takes you to England?’ he asked.

Sir William smiled, eyes lidded. ‘The King’s business,’ he said.

Chaucer threw back his head and laughed. ‘Damn me, I had that coming. Very well, William. I promised Monsieur Froissart that you were the man to tell him about Italy.’

Froissart leaned forward like an eager dog. ‘My lord will understand that one collects tales of arms. Deeds of arms – battles, wars, tournaments. At the court of the young King, one hears many tales of Crecy and Poitiers and the wars in France, but one hears little of Italy. That is,’ – he hurried on – ‘that is, one hears a great deal of rumour, but one has never had the chance to bespeak a famous knight who has served—’ he paused. ‘My lord.’

Sir William was laughing softly. ‘Well, I love to talk as I love a pretty face,’ he said.

‘By our lord, that’s the truth,’ Chaucer observed.

‘What is your name, ma petite?’ the knight asked the serving maid.

‘Aemilie, my lord,’ she said, with another stiff-backed curtsey.

Sir William had begun to turn away, but he froze and his eyes went back to hers, and she trembled.

‘That is a name of great value to me, ma petite. I have loved a lady par amours, and that is her name.’ He nodded. ‘Fetch us two more of the same, if you will be so kind.’

She curtseyed and walked away, trying to glide in her heavy skirts.

‘If you want Italy, then you will not want France,’ he said. ‘How do I begin?’

Froissart shook his head. ‘When talk turns to feats of arms, one is all attention,’ he said. ‘One is as interested in Poitiers as any other passage of arms. It was, perhaps, the greatest feat of arms of our time.’

Sir William glared at him. ‘So kind of you to say so,’ he snapped.

Froissart paled.

‘Don’t come it the tyrant, William!’ Chaucer said. ‘He means no harm. It is merely his way. He’s a connesieur of arms, as other men are of art or letters.’ He put a hand out. ‘I saw your sister a week or more ago.’

Gold smiled. ‘In truth, I cannot wait to see her. Is she well?’

Chaucer nodded. ‘I cannot say she’s plump, but she had her sisters well in hand. She was en route to Clerkenwell to deliver her accounts, I think.’

Sir William turned to Froissart. ‘My sister is a prioress of the Order of St John, monsieur.’ He said it with sufficient goodwill that Froissart relaxed.

‘I would be most pleased if you would share with me your experiences at Poitiers,’ Froissart continued. ‘Another knight’s account would only help—’

Chaucer and Gold laughed together.

Aemilie appeared at the table with her father and two men, and they began to place small pewter dishes on the table – a dish of sweet meats, a dish of saffroned cakes, and a beautiful glazed dish of dates, as well as two big-bellied flagons of wine.

Sir William rose and bowed to the master of the house. ‘Master, your hospitality exceeds anything in Italy; it is like a welcome home to England.’

The innkeeper flushed at the praise. ‘Calais is England, my lord,’ he acknowledged.

Sir William indicted his companions. ‘I’m going to bore these two poor men with a long story,’ he said. ‘Please keep the wine coming.’

Chaucer rose. ‘William, I’m for my bed. I know your stories.’

‘I’ll tell him all your secrets,’ Gold said.

Chaucer smiled his thin, elven smile. ‘We’re in the same business,’ he said. ‘He knows all my secrets.’

Again, the silence.

This time, Chaucer broke it. ‘Will I see you in London?’

Sir William nodded. ‘I shall look forward to it. Will your business be long?’

Chaucer shook his head. ‘I hope not, par dieu. I’m too old to be a courier.’ He gave a sketchy bow and headed for the stairs.

Froissart, left almost alone with the knight, had a little of Aemilie’s look. John de Blake watched his master. ‘Shall I withdraw?’ he asked.

Gold gave a half-smile to his squire. ‘Only if you want to go, John.’

De Blake settled himself in his seat and poured himself more wine.

Aemilie crossed from her counter to the wall and stood against it, ready to serve.

Sir William drank some wine and glanced at the young woman. Then he turned back to Froissart. ‘Do you really want to hear about Poitiers, monsieur?’ he asked.

Froissart sat up. ‘Yes!’ he replied.

Gold nodded. ‘I wasn’t a knight then,’ he said.

You want the story of Poitiers, messieurs? Well, I was there, and no mistake. It was warmer there – I fought in the south for several years, and I can tell you that the folds of Gascony are no place to farm, but a fine place to fight. Perhaps that’s why the Gascons are such good fighters.

Par dieu. When I began the path that would take me to chivalry, I was what? Fifteen? My hair was still red then and my freckles were ruddy instead of brown and I thought that I was as bad as Judas. I played Judas in the passion play – shall I tell you of that? Because however you may pour milk on my reputation, I was an apprentice boy in London. And in the passion plays, it’s always some poor bastard with red hair, and that described me perfectly as a boy: a poor bastard with red hair.

It shouldn’t have been that way. My parents were properly wed. My da’ had a coat of arms from the King. We owned a pair of small manors – not a knight’s fee; not by a long chalk – but my mother was of the De Vere’s and my father was a man-at-arms in Wales. I needn’t have been an apprentice. In fact, that was my first detour from a life of arms, and it almost took me clear for ever.

I imagine I’m one of the few knights you’ll meet who’s so old that he remembers the plague. No, not the plague. The Great Plague. The year everyone died. I went to play in the fields, and when I came home, my mother was dead and my father was going.

It changes you, death. It takes everything away. I lost my father and mother and all I had left was my sister.

I’ll tell you of knighthood – and war, and Poitiers, and everything, but with God’s help, and in my own time.

My father’s brother was a goldsmith. In my youth, a lot of the young gentry went off to London and went to the guilds. Everything was falling apart. You know what I’m telling you? No? Well, monsieur, the aristocracy – let’s be frank: knighthood, chivalry – was dying. Taxes, military service and grain prices. Everything was against us. I remember it, listening to my father, calm and desperate, telling my mother we’d have to sell our land. Maybe the plague saved them. I can’t see my mother in a London tenement, her husband some mercer’s worker. She was a lady to her finger’s ends.

My uncle came and got us. Given what happened, I don’t know why he came – he was a bad man and I was afraid of him from the first. He had no Christian charity whatsoever in him, and may his soul burn in hell for ever.

You are shocked, but I mean it. May he burn – in – hell.

He came and fetched us. I remember my uncle taking my father’s great sword down from where it hung on the wall. And I remember that he sold it.

He sold our farms, too.

I remember riding a tall wagon to London with my sister pressed against my side. Sometimes she held my hand. She was a little older and very quiet.

I remember entering London on that wagon, sitting on a small leather trunk of my clothes, and the city was a wonder that cut through my grief. I remember pointing to the sights that I knew from my mother and fath

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...