- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

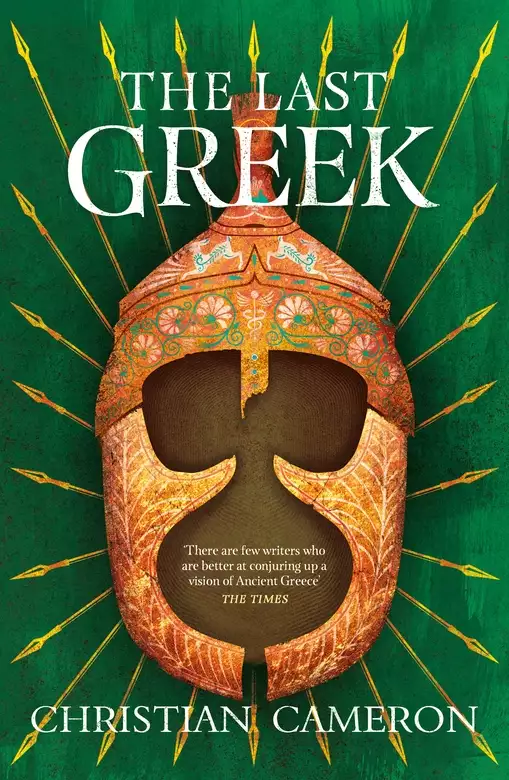

Few writers are better at conjuring up a vision of Ancient Greece'

THE TIMES

* * * * * * *

210BCE.

The most powerful empires in the world brawl over the spoils of a declawed Greece.

Philopoemen has a vision to end the chaos and anarchy that consumes his homeland - to stop the endless wars and preserve the world he loves. He must resist the urge of the oligarchs to surrender to their oppressors and raise an army to defend his countrymen from the all-conquering powers of Sparta, Macedon and Rome.

It is the last roll of the dice for the Achean League. The moment Philopoemen has been training for his whole life.

The new Achilles is poised to restore the glory of the former empire. To herald a new era.

To become the last great hero of Greece.

* * * * * * *

Praise for Christian Cameron:

'One of the finest writers of historical fiction in the world' BEN KANE

'The master of historical fiction' SUNDAY TIMES

'A storyteller at the height of his powers' HISTORICAL NOVEL SOCIETY

Release date: April 16, 2020

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Last Greek

Christian Cameron

Four things I think perhaps you need to know before you read this book.

First, Ancient Greek cavalry did not have stirrups. If you think too many riders are falling off horses here, or if you think that Alexanor has too much trouble mounting, I recommend you go out and ride rough terrain without stirrups, or just stand on flat ground and try to mount a fourteen-hand horse. It can be done, but ancient cavalry manuals (like Xenophon’s Cavalry Commander, which I recommend to all) are full of advice on mounting.

As a corollary to the first point, wrestling on horseback, which continued to play a major role in mounted combat into the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, would have been an even more vital part of mounted combat in Philopoemen’s time. The press of a cavalry fight could be as close as an infantry fight . . .

And my thanks to Georgine and Ridgely Davis for their tutelage and advice on all things equine; and to Elizabeth Usher and John Conyard for their examples.

Second, the calendar used by my protagonists is the Boeotian calendar, which I chose for various reasons, not least of which is that the Argosian calendar was not fully realised. But in brief: every Greek polis had its own calendar; even inside the Achaean League each city probably kept its own calendar. This is because of religion; every city had its own festivals and its own worship dates. Because there was nothing like a religious ‘authority’ above the level of the polis, there was no one to rectify calendars. This makes dating anything quite challenging, and so I freely admit that I have taken some small liberties with the calendar to allow for chapter titles that will, I hope, help the reader sort the pace of the action. Note there are only ten months in the Boeotian calendar . . .

Boeotian Calendar

Bucatios (January–February)

Hermaios (February–March)

Prostaterios (March–April)

Agrionios (April–May)

Homoloios (May–July)

Theilouthios (July–August)

Hippodromios (August–September)

Panamos (September–November)

Pamboiotios (November–December)

Damatios (December–January)

Attic Calendar

Hekatombaion (July–August)

Metageitnion (August–September)

Boedromion (September–October)

Pyanepsion (October–November)

Maimakterion (November–December)

Poseideon (December–January)

Gamelion (January–February)

Anethesterion (February–March)

Elaphebolion (March–April)

Mounichion (April–May)

Thargelion (May–June)

Skirophorion (June–July)

The third point is about the study of history. When dealing with the ancient world, there are too few facts and too many accepted assumptions. An issue as apparently obvious as the date of the Spartan seizure of Tegea (scholars are divided even on what year this took place), or the military effectiveness of various troop types (an area where wargamers have made assumptions that now haunt mainstream history), or what Philopoemen’s political ideals really were . . . We sift the evidence for pot sherds that we might be able to fit together into a story.

And finally, yes, it’s true. I’m not a fan of Sparta. Neither militarism nor brutality appeal to me. You be the judge.

Christian Cameron

Toronto, 2019

Prologue

Epidauros, Peloponnese

7 THARGELION (ATTIC) OR 14 THEILOUTHIOS (BOEOTIAN) (EARLY JUNE), 210 BCE

The moment before dawn: the sacred precinct of Epidauros seemed to hang in a timeless darkness, the white marble of the sanctuary’s precious buildings mere pale blurs against the stronger shadows; and then, as light touched the rim of the world beyond the mountains to the east, suddenly there was the sound of birds, the lower tones of insects, and the salmon pink of rosy-fingered dawn reached to touch the pillars of the temple, the columns of the stoa, the floor and seats of the theatre and the walls and marble roofs of the houses of healing. For a breath, the grey was touched in rose, and then the dawn swept over the sanctuary of the healing god like a reckless pink cavalry charge.

Alexanor of Kos and his wife Aspasia stood at different altars – he at the altar of Apollo, the god himself, and she at the altar of Hygeia, goddess of health – nor did they exchange even a glance, and yet Alexanor was aware of her, and aware, too, of the old priest, Sostratos, watching his every ritual motion, and Leon, his friend and vicar, swirling a censer over the head of the sacrifice.

The bull roared and turned his head towards the incense burner, and in that moment, Alexanor’s knife slashed, and the bull’s head came down. Blood poured from its open throat and its mighty knees buckled, and then it fell forward even as Alexanor stepped to the side to avoid the splash of crimson blood on his white robes.

The blood of the sacrifice ran like bright red wine in the grooves cut for the purpose, and a dozen under-priests began to cut the dead animal. A thigh bone wrapped in thick fat and tied with bloody tendons was placed on the altar before Alexanor by a stone-faced novice. He raised the thigh bones in supplication and then placed them on the brazier, full of charcoal and burning like an ironsmith’s furnace.

The smell of sizzling fat filled the temple, overwhelming the more delicate notes of frankincense.

Alexanor’s stomach rumbled loudly enough for Leon to hear it and the two men exchanged a smile. After four days of fasting, the smell of rich animal fat was as enticing as the ritual itself.

One of the local priests frowned, as if the rumble of Alexanor’s stomach was an impiety, and Alexanor wondered what was wrong. He’d sensed a coldness from the priests, even some of those he’d trained with.

Across the temple, Sostratos completed his own sacrifice and put the thigh bones of a ram on his lit brazier. At the northern end of the complex, Aspasia and two other priestesses finished their own litanies and placed a series of shaped barley cakes on the fires of their altars, so that the smells of the sacrifices mingled, rising to the gods.

Two junior priests stripped naked, pulling their spotless white himations off and laying them over the waiting arms of acolytes, to begin the serious business of butchering the ritual meat. The ram and the bull sacrificed in honour of the birth of the god Apollo would feast every man and woman in the sanctuary, from illustrious guests and healing patients to the newest slaves.

Alexanor and Leon paced down the nave of the temple, surrounded by novices; Sostratos joined them from the second altar, and another priest, Erenida, joined them from the west altar. The numbers swelled until they were a procession of all the priests and priestesses of the vast temple complex; the ceremonial priests and the healers too, and all the novices and many of the guests, the pilgrims, and the sick able to walk. On this, the principal god’s birthday, the procession, led by the sacrificers and the incense bearers, made the rounds of the sacred precinct of the whole sanctuary. At the great gates, where travellers and pilgrims were received, a choir of initiates sang the paean. At the northern gate, a choir of priestesses sang, their high voices carrying in the clear morning air.

Leon swung his silver censer with grace and Alexanor was proud for his friend, who had once been a slave and now was a senior priest, leading other priests in the most important ritual of the year. Leon walked at the head of the procession with a dignity that those who did not know him might have missed in his day-to-day humour and impatience with authority; in a ceremony, he became a pillar of piety.

Finally, after the procession had blessed every altar, visited every building, it wound its way back to the high altar of the Temple of Apollo where Chiron, the old hierophant of the temple complex, waited on the steps, leaning on his cornel-wood staff.

He intoned the ritual of welcome as they practised it at Epidauros, and Alexanor and a hundred other initiates sang the response. They all lifted their arms and sang the paean again, three hundred voices raised together, and the ceremony was completed.

Alexanor caught his wife’s eye on him and he smiled, and she returned his smile, turned and spoke to one of the other priestesses, Kleopatra, who grinned.

‘After the feast,’ she said softly.

Close contact between male and female priests was discouraged, at least in public, and even when they were married. Alexanor deplored the rule, but found the need to communicate secretly with his wife – to flirt with her eyes, to pass messages – had its charms. He grinned, and Leon rolled his eyes, and the two of them carried their ritual instruments out of the crowd. Having completed important parts of the ceremony, they were now responsible for cleaning everything.

Alexanor followed Leon into the skeuotheke, the small building that acted as a treasury and a ritual storage house. Inside, amid the hanging lamps of gold and silver and bronze, stacks of silver platters and gold bowls worth a fortune, there was a small, very ordinary wooden table against one of the barred windows. There the two men emptied the precious censer, dumping the hot coals and the unburnt crystals of resin into an old iron pot with a close-fitting wooden lid that extinguished the burning material and rendered it inert.

Leon hung the thurible from a bronze hood near the window, where the hot metal could cool safely.

‘Like old times,’ he said wryly.

Alexanor returned his smile. ‘Better than old times. We’re senior priests.’

‘We’re still polishing the thuribles,’ Leon noted. ‘And not everyone here loves us. Remind me, why are we here?’ he asked quietly.

‘We’re here because Chiron requested our presence for the god’s year-day procession,’ Alexanor said.

Leon was busy using a tuft of flax-tow dipped in ash to polish a spot off one of the ritual platters. A long queue of acolytes now stood outside the doors of the skeuotheke, with armloads of silver vessels and lamps that had been used for the bull’s heart, the ram’s heart, the sacred fire, and a dozen other liturgical purposes.

‘By my count, this place still has more than seventy initiates, and thirty priests, any one of whom could have conducted the whole blessed thing,’ Leon said. ‘Sostratos, for example.’

Alexanor went back out to the portico and received another armload of ritual vessels, which he brought in and set carefully on the table.

‘Chiron asked for us,’ he said.

‘Why?’

‘I agree that not everyone here loves us,’ Alexanor said. ‘I assumed some of the juniors were jealous that we were asked to lead the sacrifice.’ He shrugged, as if dismissing the subject which was, he thought, unworthy. Seizing the moment, he asked, ‘Have you ever considered marriage?’

Leon’s hand froze. ‘What?’ he asked, startled. ‘Is this your notion of how to change the subject?’

Alexanor went out, got two trays from a young Gaulish slave, and asked for a bucket of clean water. Then he went back inside, where he began to wipe down the silver.

‘Yes,’ Alexanor answered. ‘That’s how I change the subject. I assume Chiron has his reasons, which might be anything from an attempt to improve the unity of the sanctuaries of Asklepios to a friendly desire to see us.’ He glanced at Leon. ‘And we needn’t gossip about the priests.’

‘By the god, you are not curious?’ Leon asked.

‘My curiosity is of a piece with my hunger,’ Alexanor said. ‘Soon to be assuaged. So why dwell on it?’

‘What a Stoic you are, to be sure,’ Leon grumbled. ‘Philopoemen is rubbing off on you.’

Alexanor allowed himself a smile. ‘I’m as curious as you are,’ he admitted. He shrugged. ‘But my curiosity won’t get these platters clean.’

The feast was superb, and conjured images of bygone days. Alexanor had spent six happy years in the sanctuary of Epidauros and Leon had spent even longer. The great feast of Apollo had always been a favourite festival, with dancing, abundant food including beef and lamb, and elaborate sweets, amphorae of wine from all over the Hellenic world, and important guests, with speeches, song, and sometimes even presents.

Now, reclining on a couch with Leon at his side, Alexanor remembered his last feast of Apollo, and all the events that followed after it: the attack of the Spartans on the sanctuary, led by Machanandas, and his first sight of Philopoemen as an apparent corpse flung over the back of a riderless horse.

Epidauros was a more conservative temple than Lentas, where Alexanor was hierophant, and he reclined with Leon because men and women feasted separately in Epidauros, even when they were married and shared children. Alexanor could hear the sound of his wife’s laughter through the leather screen that divided the hall, and he could hear the even higher laughter of Kleopatra, his wife’s new friend.

‘I like the procession at Lentas better,’ Leon grumbled. ‘With all the priests and priestesses from Gortyna, and the cavalry, and the phalanx.’

Alexanor took a sip of watered wine and passed the bowl to Leon.

‘It is odd, isn’t it? To have the sanctuary so—’

Leon lay back. ‘Dominant. I like our balance better.’

Kleopatra laughed again.

‘They’re having too much fun,’ Alexanor said.

‘The local priestess of Hygeia is less …’ Leon smiled. ‘Less staid than I’d have expected.’

‘Aspasia says that she’s very well trained and actually lived in Alexandria for three years.’

‘What if Chiron wants to send an embassy?’ Leon asked.

‘An embassy?’

‘Don’t be overmodest. He sent you to the king of Macedon eight years ago – that’s what started all this. Don’t be coy. Last year Kos sent you to Philip. Both Epidauros and Kos used you to stay in touch with Philopoemen.’

‘I take it we’ve returned to the subject of why we were summoned here,’ Alexanor said.

‘You used to be more fun. Shall I tell everyone about how you took Phila’s pulse?’

‘Only if you want to die in the dining hall at Epidauros,’ Alexanor growled.

‘Good, good, just making sure you are still in there, because the Stoic Hierophant of Lentas is a dull fellow indeed.’

‘I’m thinking of how much of old Heraclitus’ river of time has flowed past my toes since I last lay here in this hall.’ Alexanor looked up at a line of shields dedicated by the former king of Macedon. ‘When last I lay here for a feast, Doson was still king of Macedon. It was after the Feast of Apollo that Chiron sent us to Doson, as you say.’

‘And Philopoemen won the Battle of Sellasia,’ Leon said. ‘Almost single-handed, as I seem to remember.’

‘There’s a little hyperbole there,’ Alexanor said.

I met Phila. And fell in love with a courtesan.

‘And then he received an ovation at Nemea,’ Leon said.

‘Doson received the ovation—’

‘It was for Philopoemen and his Greeks. I was there. The old king was mortified.’

‘He was quite cheerful, really,’ Alexanor said. ‘All right, I admit it, the ovation was mostly for the Achaeans and Philopoemen.’

‘And then Philopoemen declined to serve the king, and then we failed to keep the old fellow from drinking himself to death.’

‘We?’

‘And then you lured Philopoemen to Crete.’

‘What happened to “we”?’

‘That was all you. You wanted to be hierophant. I got to pretend to be your slave. You beat me cruelly.’

‘You deserved it.’

‘You two are laughing too damned hard,’ Sostratos said, leaning over their kline.

‘Have a seat and we’ll make you laugh too,’ Leon said.

The older priest was laughing already. ‘I don’t remember you two as troublemakers. Mostly Alexanor pouted and moped and Leon did all the work.’

‘Very little has changed,’ Leon said.

‘So about your marriage,’ Alexanor said.

Leon whirled, almost dumping Sostratos onto the floor. But he recovered.

‘Can you tell us, reverend sir, why the Hierophant has honoured us with an invitation?’

Sostratos nodded. ‘I imagine that I could, at that. But I won’t, because I’m a cruel bastard. Also because Chiron is old, but I still fear him.’ He poked Alexanor. ‘The truth is that we all miss you.’ He raised an eyebrow. ‘Despite everything.’

‘And you’re finally old enough to actually be a senior priest,’ Erenida said, sitting on the low table that was supposed to hold their food. ‘When you were here before—’

‘Now I remember why I went away,’ Alexanor said, clasping Erenida’s hand with a laugh. ‘How’s old Bion?’

‘Still hale. A freedman now, of course – he’s training initiates.’

‘I imagine he keeps them in a state of gentle terror.’

‘Pretty much,’ Erenida agreed. He frowned. ‘It’s been a difficult time,’ he admitted. ‘And you two aren’t making it easier.’

Sostratos nodded. ‘We’re not far enough from Sparta to escape the effects of the new tyrant there. Remember the young scapegrace who tried to invade the precinct? Machanandas?’

‘All too well,’ Alexanor responded.

‘He’s the Tyrant of Sparta now. He rules in the name of the young king, of course, but in reality, he does whatever he wants. He’s worse than Cleomenes ever was. He has some trumped-up document claiming that the sanctuary is part of the royal domains of the Lacedaemonians – he’s demanded a tithe of our treasury.’

Alexanor shook his head. ‘You can appeal to the League.’

‘The League is a broken stick,’ Sostratos said. ‘An old dog without any teeth. The wolves don’t fear her any more.’

‘I thought that’s why Macedon summoned Philopoemen,’ Leon said.

Erenida frowned. ‘Why was Philopoemen of Megalopolis even on Crete? As a mercenary?’ He made a face. ‘I’ve heard some nasty tales about him, and I know he’s your guest-friend.’

Leon drank some wine. He glanced at Alexanor.

Alexanor smiled. ‘The Achaean League sent Philopoemen to Crete to save the League of Crete from the Spartans and the Aegyptians.’

‘And the Rhodians and the Romans,’ Leon said.

Erenida frowned. ‘What?’ He shook his head. ‘What in Hades does Achaea have to do with Crete?’

Leon nodded over the rim of the kylix. ‘Everything. Grain, slaves, mercenaries, ties of guest-friendship, and the seasonal winds that blow from here to there.’

‘You must know,’ Sostratos said. ‘Sparta holds cities on Crete.’

‘Macedon needed Crete to be stable.’ Alexanor said.

Erenida shrugged. ‘I’m a simple priest. And I confess I’d heard a very different story from one of the other priests. Of Philopoemen serving as a sort of bandit king, murdering and raping his way across Crete for profit. And sacking the sanctuary at Lentas.’

‘Sacking the sanctuary?’ Alexanor asked. ‘Who said such a thing?’

Leon’s vulpine face took on a nasty smile. ‘Can’t you guess? Someone who hates Philopoemen. And you, too, I would wager.’

Erenida shrugged. ‘No friend of yours, it is true. Pausanias of Gortyna.’

‘Is he here?’

‘He’s at Messene, minding the temple there as part of his duties.’ Erenida shrugged.

‘I replaced him,’ Alexanor said. ‘I sent him here under arrest.’

‘Ahh,’ Erenida said. ‘I’ve stepped in it again.’

Alexanor nodded. ‘Philopoemen went to Crete at the command of Aratos and the League. With fewer than a hundred men, he retook Gortyna, refounded the Cretan League, built an army, and defeated the oligarchs utterly.’ He smiled. ‘He’s a very able general.’

‘And now Philip of Macedon wants him to command the Achaean League,’ Sostratos said.

Alexanor nodded. ‘Where is this going?’ he asked.

Sostratos shook his head. ‘The whole world is at war. And the war is coming to Epidauros. Like it or not, you and your friend are players in that war, and we have to take an interest in these events if we are going to survive.’

Erenida shook his head. ‘Call me old-fashioned.’

Leon smiled. ‘You are the very definition of old-fashioned,’ he said. ‘When I was a slave, you were the most conservative, most aristocratic novice.’

Erenida raised his eyebrows in acknowledgement. ‘Of course. Regardless, we are priests. It is not our business what happens beyond our precinct walls. Let this Philopoemen march about – we should pray, and interpret dreams.’ He took the kylix, drank, and then rose. ‘I’ll make sure some other couches have wine.’

When he was gone, Sostratos settled in his place.

‘He’s not as bad as he sounds.’

‘He never was,’ Leon said. ‘He always spoke like one of the Kalos Kagathos, the beautiful people, but he treated me better than most of the other novices. And since I became a priest, he simply assumes I’m a gentlemen. I prefer that to many of the other attitudes I’ve encountered, I promise you.’

Alexanor looked puzzled. ‘Chiron has trusted Pausanias with a temple?’ he asked.

Sostratos shrugged. ‘Pausanias is a very rich, very difficult man. What did you expect – that we’d execute him?’ He laughed. ‘I probably have the only sword in the precinct.’

‘I have a sword,’ Leon said.

‘And I, too,’ Alexanor said. ‘Life on Crete was violent.’

‘And that’s what’s coming here,’ Sostratos said. ‘The thing that I’m surprised Erenida didn’t mention is …’ He looked around. ‘You two are quite notorious, these days.’

‘Notorious?’ Leon said.

‘Dissections,’ Sostratos said very quietly. ‘The open study of internal anatomy.’

Alexanor nodded slowly. ‘Ahhh. Now I understand why I’m here.’

‘No,’ Sostratos said, ‘you don’t. Chiron approves of your study of anatomy, and anyway, you have the approval of the House on Kos. But the old-fashioned priests are not your friends, and your Pausanias has made you sound as dangerous as he could manage. He’s a sly serpent. You should be wary of him.’

‘Erenida seemed fine,’ Leon said.

Sostratos looked around. ‘He’s a decent fellow, for one of the very rich. But you need to be wary. Chiron placed you in charge of the ceremony to make a statement – but there are priests here who resent you.’

‘We noticed,’ Alexanor admitted.

Chiron wasn’t sitting in his cell. Instead, a brown-clad slave led them out to the second storey of the stoa, where the old priest was leaning on the railing, looking out over the distant mountains.

‘Well done,’ he said, clasping Leon’s hand, and then again, when he took Alexanor’s. ‘Well done.’

‘The ceremony?’ Alexanor asked.

‘Bah. That too. No, your life. The sanctuary at Lentas. Your handling of Philopoemen. The way you both rebuilt the reputation of your temple – everything. Both of you have justified every trust that was placed in you.’

Both of the younger men smiled; indeed, each of them glowed, although in very different ways. Leon, the former slave, grinned from ear to ear, and stood straighter, while Alexanor, the Rhodian aristocrat, gazed embarrassedly out over the valley, an untameable smile forcing itself on his face. Praise from the old priest was rare indeed; such open, absolute praise was worth a decade of work.

‘But the reward for all your hard work is more work.’ Chiron nodded. He moved stiffly. ‘War is coming.’

‘Sostratos said as much.’

‘I asked him not to say too much.’ Chiron made a face. ‘For the first time under my rule, I’m sorry to say, there is dissension inside the sanctuary. I suspect that many of the younger priests are counting the days until I die and planning for the succession here.’ He shrugged, as if this was of no moment. ‘In the meantime, gentlemen, I have called on you to ask your political help, and, I think, your medical help as well.’

Alexanor bowed, Leon waved for the older priest to go on.

‘A month ago, the Romans took the island of Aegina.’

‘We know,’ Leon said. ‘We passed south of their fleet on our way here. We could see their warships.’

Chiron nodded. ‘They are barbarians, not Greeks. They sacked every temple they took. Stripped the altars and the treasuries – looted even the hangings and the bronze decorations on the statues. Aegina! One of the richest islands in the Greek world.’

‘And a member of the Achaean League,’ Alexanor added.

‘This is no longer a squabble between warlords,’ the old priest said. ‘When Macedon and the Seleucids spar over Syria or Boeotia, they do not sack temples. We are every bit as vulnerable as Aegina. The Roman fleet could be here at any time. The League fleet is at Corinth, and if they have ten warships I’d be surprised.’

‘And the Romans have been joined by Attalos of Pergamum,’ Alexanor said. ‘Two great fleets.’

‘There’s a rumour that the Carthaginians have promised Philip of Macedon a fleet,’ Chiron said. ‘Let me be brief. As long as I have been hierophant, we have tried to stay free of entanglements with politics. But we have always remained aware of the world around us. Now I fear we must do more. I want you, Alexanor, to go to the Synodos of the Achaean League and speak for us as an institution, almost as if we were a constituent city. I need to know if the League will defend us – fight for us, if necessary.’

Alexanor nodded. ‘You want me to talk to Philopoemen?’

Chiron glanced at him, his eyes hard. ‘Yes and no. Your friend Philopoemen returns to us with a very … tough … reputation. Most of the rich men of the Peloponnese fear him as a radical and worry about him as a potential Macedonian satrap. And even Philip seems to have … doubts. I am not sure that we can rely on Philopoemen to protect us. On the other hand, your credit must be high with all the Achaeans – you reformed the sanctuary at Lentas and supported Philopoemen.’

‘So am I going as an ambassador?’

‘A representative,’ Chiron said, placing particular emphasis on the word.

‘What do we have to offer the League?’ Alexanor asked.

‘Who’s going to run the sanctuary at Lentas?’ Leon asked. ‘I do not mean to be difficult, sir, but we are a joint foundation of Epidauros and Kos, now. We cannot just abandon our charges.’

Chiron nodded. ‘I’m going to ask you, Leon, to direct Lentas, so that I can have Alexanor for a year.’

‘A former slave as an acting hierophant?’ Leon asked. ‘Now who is a radical?’

‘There’s more, I’m afraid. I want you to take half a dozen of my juniors and train them in anatomy. And I’ll tell you up front that I’m giving you the whole of a faction – a virulent faction.’

‘An aristocratic faction?’ Leon asked.

‘Yes.’

‘So, I – the former slave – will be teaching unorthodox medical techniques to men who question my birth and fitness?’ he asked.

‘Exactly,’ the old priest said.

Leon smiled. ‘Well, well. You really do think I’m capable. I’m flattered.’

‘Leon gets to run my sanctuary while I ride around the Peloponnese nattering with politicians?’ Alexanor asked.

‘Exactly,’ Chiron said. ‘Just so.’

Alexanor shook his head. ‘Of course I’ll obey. But it does seem that Leon will have more fun.’ He bowed. ‘And may Aspasia accompany me?’

Chiron waved his hand. ‘Your wife? No, no. It wouldn’t be fitting.’

‘Perfect.’ Alexanor’s bitterness threatened to boil over.

And at the end of the interview, when they were alone in the great stoa of the temple’s headquarters, Alexanor glanced at Leon.

‘Was I too happy?’ he asked. ‘I have a house. A family!’

Leon put his hand on his friend’s shoulder. ‘Brother,’ he said, ‘I think our mentor is trying to tell us that the whole of the Greek world is under threat.’

‘I understand that,’ Alexanor snapped. ‘My utterly unworthy thought is that I’ve done my service …’

Leon smiled.

‘I’m not even sure how to tell Aspasia,’ he said. ‘Damn.’ He looked over at Leon. ‘I’m being difficult. Congratulations, Leon. You fully deserve to run a sanctuary. You’ll probably be better at it than I was.’

‘It’s only temporary.’

Alexanor shook his head. ‘No, Chiron wants me to leave Lentas. I suspect …’ He looked out into the evening light. ‘Never mind. Now you should consider marriage.’

‘Why do you keep harping on about marriage?’ Leon asked.

‘Because it’s so—’

Leon laughed. ‘Wonderful? I can hear your baby cry, brother, and you and Aspasia seem to manage a spat a day. No thanks.’

Alexanor shrugged. ‘You’re wrong. The fights are nothing. The companionship is everything.’ He looked at his friend in the failing light. ‘If you are to be hierophant, you’d find it useful to have a companion that you trust.’

‘Are you matchmaking?’

‘Aspasia is,’ Alexanor admitted.

‘Someone I know?’ Leon asked. ‘Not Kleopatra!’

‘She’s incredibly well trained. She’s not just a midwife. She’s—’

‘The perfect recommendation for a wife,’ Leon snapped. ‘She’s a fucking aristocrat, the daughter of Arkadian nobles, she’s almost half my age, and I can’t stand her laugh.’ He snorted. ‘And she has flaming red hair.’

‘You’re right, that clinches it,’ Alexanor said. ‘By the god, I don’t want to tell Aspasia …’

‘She’s a tough nut. Although it suddenly occurs to me that she won’t be coming with me back to Lentas.’

They stood at the edge of the portico, watching the night fall across the sanctuary.

‘I knew when we were summoned that it was all going to change,’ Alexanor admitted. ‘I brought the children because I suspected I wouldn’t be c

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...