- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

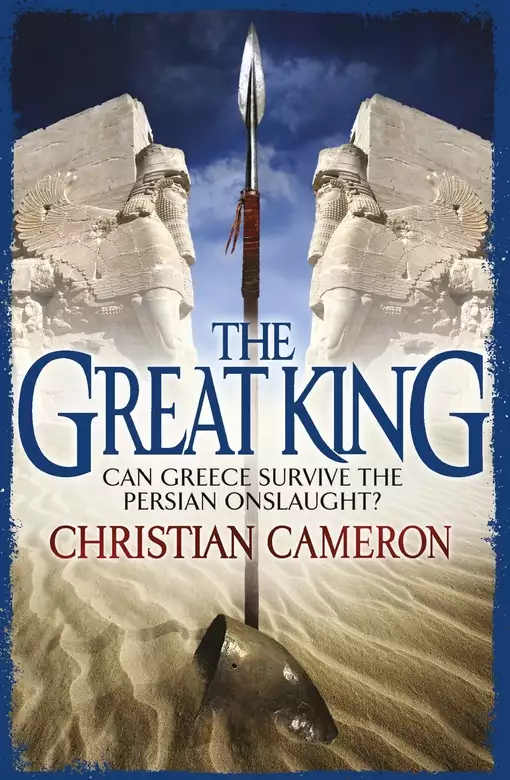

The heroic story of Arimnestos of Plataea continues — a thrilling historical adventure set amid the epic struggle between Greece and Persia — perfect for fans of the blockbusting film 300.

Slave, pirate, husband and lover: Arimnestos of Plataea has been many things in the course of his life. But men remember him best as one of the heroes of the Battle of Marathon, the epic victory that prevented all of Greece from falling under the Persian yoke.

But now there is a new Great King on the throne, determined to succeed where his father failed. As rumours abound of a vast Persian invasion, an embassy is sent to forestall the threat.

Arimnestos is chosen to escort them — an honour he can hardly refuse. But as the storm clouds of war gather and factions on both sides begin to weave their treacherous plots, Arimnestos' journey begins to look more and more like a suicide mission.

Release date: January 2, 2014

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Great King

Christian Cameron

Akinakes A Scythian short sword or long knife, also sometimes carried by Medes and Persians.

Andron The ‘men’s room’ of a proper Greek house – where men have symposia. Recent research has cast real doubt as to the sexual exclusivity of the room, but the name sticks.

Apobatai The Chariot Warriors. In many towns, towns that hadn’t used chariots in warfare for centuries, the Apobatai were the elite three hundred or so. In Athens, they competed in special events; in Thebes, they may have been the forerunners of the Sacred Band.

Archon A city’s senior official or, in some cases, one of three or four. A magnate.

Aspis The Greek hoplite’s shield (which is not called a hoplon!). The aspis is about a yard in diameter, is deeply dished (up to six inches deep) and should weigh between eight and sixteen pounds.

Basileus An aristocratic title from a bygone era (at least in 500 BC) that means ‘king’ or ‘lord’.

Bireme A warship rowed by two tiers of oars, as opposed to a trireme, which has three tiers.

Chiton The standard tunic for most men, made by taking a single continuous piece of cloth and folding it in half, pinning the shoulders and open side. Can be made quite fitted by means of pleating. Often made of very fine quality material – usually wool, sometimes linen, especially in the upper classes. A full chiton was ankle length for men and women.

Chitoniskos A small chiton, usually just longer than modesty demanded – or not as long as modern modesty would demand! Worn by warriors and farmers, often heavily bloused and very full by warriors to pad their armour. Usually wool.

Chlamys A short cloak made from a rectangle of cloth roughly 60 by 90 inches – could also be worn as a chiton if folded and pinned a different way. Or slept under as a blanket.

Corslet/Thorax In 500 BC, the best corslets were made of bronze, mostly of the so-called ‘bell’ thorax variety. A few muscle corslets appear at the end of this period, gaining popularity into the 450s. Another style is the ‘white’ corslet, seen to appear just as the Persian Wars begin – re-enactors call this the ‘Tube and Yoke’ corslet, and some people call it (erroneously) the linothorax. Some of them may have been made of linen – we’ll never know – but the likelier material is Athenian leather, which was often tanned and finished with alum, thus being bright white. Yet another style was a tube and yoke of scale, which you can see the author wearing on his website. A scale corslet would have been the most expensive of all, and probably provided the best protection.

Daidala Cithaeron, the mountain that towered over Plataea, was the site of a remarkable fire-festival, the Daidala, which was celebrated by the Plataeans on the summit of the mountain. In the usual ceremony, as mounted by the Plataeans in every seventh year, a wooden idol (daidalon) would be dressed in bridal robes and dragged on an ox-cart from Plataea to the top of the mountain, where it would be burned after appropriate rituals. Or, in the Great Daidala, which were celebrated every forty-nine years, fourteen daidala from different Boeotian towns would be burned on a large wooden pyre heaped with brushwood, together with a cow and a bull that were sacrificed to Zeus and Hera. This huge pyre on the mountain top must have provided a most impressive spectacle; Pausanias remarks that he knew of no other flame that rose as high or could be seen from so far.

The cultic legend that was offered to account for the festival ran as follows. When Hera had once quarrelled with Zeus, as she often did, she had withdrawn to her childhood home of Euboea and had refused every attempt at reconciliation. So Zeus sought the advice of the wisest man on earth, Cithaeron (the eponym of the mountain), who ruled at Plataea in the earliest times. Cithaeron advised him to make a wooden image of a woman, to veil it in the manner of a bride, and then to have it drawn along in an ox-cart after spreading the rumour that he was planning to marry the nymph Plataea, a daughter of the river god Asopus. When Hera rushed to the scene and tore away the veils, she was so relieved to find a wooden effigy rather than the expected bride that she at last consented to be reconciled with Zeus. (Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology, pp. 137–8)

Daimon Literally a spirit, the daimon of combat might be adrenaline, and the daimon of philosophy might simply be native intelligence. Suffice it to say that very intelligent men – like Socrates – believed that god-sent spirits could infuse a man and influence his actions.

Daktyloi Literally digits or fingers, in common talk ‘inches’ in the system of measurement. Systems differed from city to city. I have taken the liberty of using just the Athenian units.

Despoina Lady. A term of formal address.

Diekplous A complex naval tactic about which some debate remains. In this book, the Diekplous, or through stroke, is commenced with an attack by the ramming ship’s bow (picture the two ships approaching bow to bow or head on) and cathead on the enemy oars. Oars were the most vulnerable part of a fighting ship, something very difficult to imagine unless you’ve rowed in a big boat and understand how lethal your own oars can be – to you! After the attacker crushes the enemy’s oars, he passes, flank to flank, and then turns when astern, coming up easily (the defender is almost dead in the water) and ramming the enemy under the stern or counter as desired.

Doru A spear, about ten feet long, with a bronze butt-spike.

Eleutheria Freedom.

Ephebe A young, free man of property. A young man in training to be a hoplite. Usually performing service to his city and, in ancient terms, at one of the two peaks of male beauty.

Eromenos The ‘beloved’ in a same-sex pair in ancient Greece. Usually younger, about seventeen. This is a complex, almost dangerous subject in the modern world – were these pairbonds about sex, or chivalric love, or just a ‘brotherhood’ of warriors? I suspect there were elements of all three. And to write about this period without discussing the eromenos/erastes bond would, I fear, be like putting all the warriors in steel armour instead of bronze . . .

Erastes The ‘lover’ in a same-sex pair bond – the older man, a tried warrior, twenty-five to thirty years old.

Eudaimonia Literally ‘well-spirited’. A feeling of extreme joy.

Exhedra The porch of the women’s quarters – in some cases, any porch over a farm’s central courtyard.

Helots The ‘race of slaves’ of Ancient Sparta – the conquered peoples who lived with the Spartiates and did all of their work so that they could concentrate entirely on making war and more Spartans.

Hetaira Literally a ‘female companion’. In ancient Athens, a hetaira was a courtesan, a highly skilled woman who provided sexual companionship as well as fashion, political advice and music.

Himation A very large piece of rich, often embroidered wool, worn as an outer garment by wealthy citizen women or as a sole garment by older men, especially those in authority.

Hoplite A Greek upper-class warrior. Possession of a heavy spear, a helmet and an aspis (see above) and income above the marginal lowest free class were all required to serve as a hoplite. Although much is made of the ‘citizen soldier’ of ancient Greece, it would be fairer to compare hoplites to medieval knights than to Roman legionnaires or modern National Guardsmen. Poorer citizens did serve, and sometimes as hoplites or marines, but in general, the front ranks were the preserve of upper-class men who could afford the best training and the essential armour.

Hoplitodromos The hoplite race, or race in armour. Two stades with an aspis on your shoulder, a helmet and greaves in the early runs. I’ve run this race in armour. It is no picnic.

Hoplomachia A hoplite contest, or sparring match. Again, there is enormous debate as to when hoplomachia came into existence and how much training Greek hoplites received. One thing that they didn’t do is drill like modern soldiers – there’s no mention of it in all of Greek literature. However, they had highly evolved martial arts (see pankration) and it is almost certain that hoplomachia was a term that referred to ‘the martial art of fighting when fully equipped as a hoplite’.

Hoplomachos A participant in hoplomachia.

Hypaspist Literally ‘under the shield’. A squire or military servant – by the time of Arimnestos, the hypaspist was usually a younger man of the same class as the hoplite.

Kithara A stringed instrument of some complexity, with a hollow body as a soundboard.

Kline A couch.

Kopis The heavy, back-curved sabre of the Greeks. Like a longer, heavier modern kukri or Gurkha knife.

Kore A maiden or daughter.

Kylix A wide, shallow, handled bowl for drinking wine.

Logos Literally ‘word’. In pre-Socratic Greek philosophy the word is everything – the power beyond the gods.

Longche A six to seven foot throwing spear, also used for hunting. A hoplite might carry a pair of longchai, or a single, longer and heavier doru.

Machaira A heavy sword or long knife.

Maenads The ‘raving ones’ – ecstatic female followers of Dionysus.

Mastos A woman’s breast. A mastos cup is shaped like a woman’s breast with a rattle in the nipple – so when you drink, you lick the nipple and the rattle shows that you emptied the cup. I’ll leave the rest to imagination . . .

Medimnos A grain measure. Very roughly – 35 to 100 pounds of grain.

Megaron A style of building with a roofed porch.

Navarch An admiral.

Oikia The household – all the family and all the slaves, and sometimes the animals and the farmland itself.

Opson Whatever spread, dip or accompaniment an ancient Greek had with bread.

Pais A child.

Palaestra The exercise sands of the gymnasium.

Pankration The military martial art of the ancient Greeks – an unarmed combat system that bears more than a passing resemblance to modern MMA techniques, with a series of carefully structured blows and domination holds that is, by modern standards, very advanced. Also the basis of the Greek sword and spear-based martial arts. Kicking, punching, wrestling, grappling, on the ground and standing, were all permitted.

Peplos A short over-fold of cloth that women could wear as a hood or to cover the breasts.

Phalanx The full military potential of a town; the actual, formed body of men before a battle (all of the smaller groups formed together made a phalanx). In this period, it would be a mistake to imagine a carefully drilled military machine.

Phylarch A file-leader – an officer commanding the four to sixteen men standing behind him in the phalanx.

Polemarch The war leader.

Polis The city. The basis of all Greek political thought and expression, the government that was held to be more important – a higher god – than any individual or even family. To this day, when we talk about politics, we’re talking about the ‘things of our city’.

Porne A prostitute.

Porpax The bronze or leather band that encloses the forearm on a Greek aspis.

Psiloi Light infantrymen – usually slaves or adolescent freemen who, in this period, were not organised and seldom had any weapon beyond some rocks to throw.

Pyrrhiche The ‘War Dance’. A line dance in armour done by all of the warriors, often very complex. There’s reason to believe that the Pyrrhiche was the method by which the young were trained in basic martial arts and by which ‘drill’ was inculcated.

Pyxis A box, often circular, turned from wood or made of metal.

Rhapsode A master-poet, often a performer who told epic works like the Iliad from memory.

Satrap A Persian ruler of a province of the Persian Empire.

Skeuophoros Literally a ‘shield carrier’, unlike the hypaspist, this is a slave or freed man who does camp work and carries the armour and baggage.

Sparabara The large wicker shield of the Persian and Mede elite infantry. Also the name of those soldiers.

Spolas Another name for a leather corslet, often used for the lion skin of Heracles.

Stade A measure of distance. An Athenian stade is about 185 metres.

Strategos In Athens, the commander of one of the ten military tribes. Elsewhere, any senior Greek officer – sometimes the commanding general.

Synaspismos The closest order that hoplites could form – so close that the shields overlap, hence ‘shield on shield’.

Taxis Any group but, in military terms, a company; I use it for 60 to 300 men.

Thetes The lowest free class – citizens with limited rights.

Thorax See corslet.

Thugater Daughter. Look at the word carefully and you’ll see the ‘daughter’ in it . . .

Triakonter A small rowed galley of thirty oars.

Trierarch The captain of a ship – sometimes just the owner or builder, sometimes the fighting captain.

Zone A belt, often just rope or finely wrought cord, but could be a heavy bronze kidney belt for war.

This series is set in the very dawn of the so-called Classical Era, often measured from the Battle of Marathon (490 BC). Some, if not most, of the famous names of this era are characters in this series – and that’s not happenstance. Athens of this period is as magical, in many ways, as Tolkien’s Gondor, and even the quickest list of artists, poets, and soldiers of this era reads like a ‘who’s who’ of western civilization. Nor is the author tossing them together by happenstance – these people were almost all aristocrats, men (and women) who knew each other well – and might be adversaries or friends in need. Names in bold are historical characters – yes, even Arimnestos – and you can get a glimpse into their lives by looking at Wikipedia or Britannia online. For more in-depth information, I recommend Plutarch and Herodotus, to whom I owe a great deal.

Arimnestos of Plataea may – just may – have been Herodotus’s source for the events of the Persian Wars. The careful reader will note that Herodotus himself – a scribe from Halicarnassus – appears several times . . .

Archilogos – Ephesian, son of Hipponax the poet; a typical Ionian aristocrat, who loves Persian culture and Greek culture too, who serves his city, not some cause of ‘Greece’ or ‘Hellas’, and who finds the rule of the Great King fairer and more ‘democratic’ than the rule of a Greek tyrant.

Arimnestos – Child of Chalkeotechnes and Euthalia.

Aristagoras – Son of Molpagoras, nephew of Histiaeus. Aristagoras led Miletus while Histiaeus was a virtual prisoner of the Great King Darius at Susa. Aristagoras seems to have initiated the Ionian Revolt – and later to have regretted it.

Aristides – Son of Lysimachus, lived roughly 525–468 BC, known later in life as ‘The Just’. Perhaps best known as one of the commanders at Marathon. Usually sided with the Aristocratic party.

Artaphernes – Brother of Darius, Great King of Persia, and Satrap of Sardis. A senior Persian with powerful connections.

Behon – A Kelt from Alba; a fisherman and former slave.

Bion – A slave name, meaning ‘life’. The most loyal family retainer of the Corvaxae.

Briseis – Daughter of Hipponax, sister of Archilogos.

Calchus – A former warrior, now the keeper of the shrine of the Plataean Hero of Troy, Leitus.

Chalkeotechnes – The Smith of Plataea; head of the family Corvaxae, who claim descent from Herakles.

Chalkidis – Brother of Arimnestos, son of Chalkeotechnes.

Cimon – Son of Miltiades, a professional soldier, sometime pirate, and Athenian aristocrat.

Cleisthenes – was a noble Athenian of the Alcmaeonid family. He is credited with reforming the constitution of ancient Athens and setting it on a democratic footing in 508/7 BC.

Collam – A Gallic lord in the Central Massif at the headwaters of the Seine.

Dano of Croton – Daughter of the philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras.

Darius – King of Kings, the lord of the Persian Empire, brother to Artaphernes.

Doola – Numidian ex-slave.

Draco – Wheelwright and wagon builder of Plataea, a leading man of the town.

Empedocles – A priest of Hephaestus, the Smith God.

Epaphroditos – A warrior, an aristocrat of Lesbos.

Eualcides – A Hero. Eualcidas is typical of a class of aristocratic men – professional warriors, adventurers, occasionally pirates or merchants by turns. From Euboeoa.

Heraclitus – c.535–475 BC. One of the ancient world’s most famous philosophers. Born to an aristocratic family, he chose philosophy over political power. Perhaps most famous for his statement about time: ‘You cannot step twice into the same river’. His belief that ‘strife is justice’ and other similar sayings which you’ll find scattered through these pages made him a favourite with Nietzsche. His works, mostly now lost, probably established the later philosophy of Stoicism.

Herakleides – An Aeolian, a Greek of Asia Minor. With his brothers Nestor and Orestes, he becomes a retainer – a warrior – in service to Arimnestos. It is easy, when looking at the birth of Greek democracy, to see the whole form of modern government firmly established – but at the time of this book, democracy was less than skin deep and most armies were formed of semi-feudal war bands following an aristocrat.

Heraklides – Aristides’ helmsman, a lower-class Athenian who has made a name for himself in war.

Hermogenes – Son of Bion, Arimnestos’s slave.

Hesiod – A great poet (or a great tradition of poetry) from Boeotia in Greece, Hesiod’s ‘Works and Days’ and ‘Theogony’ were widely read in the sixth century and remain fresh today – they are the chief source we have on Greek farming, and this book owes an enormous debt to them.

Hippias – Last tyrant of Athens, overthrown around 510 BC (that is, just around the beginning of this series), Hippias escaped into exile and became a pensioner of Darius of Persia.

Hipponax – 540–c.498 BC. A Greek poet and satirist, considered the inventor of parody. He is supposed to have said ‘There are two days when a woman is a pleasure: the day one marries her and the day one buries her’.

Histiaeus – Tyrant of Miletus and ally of Darius of Persia, possible originator of the plan for the Ionian Revolt.

Homer – Another great poet, roughly Hesiod’s contemporary (give or take fifty years!) and again, possibly more a poetic tradition than an individual man. Homer is reputed as the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, two great epic poems which, between them, largely defined what heroism and aristocratic good behaviour should be in Greek society – and, you might say, to this very day.

Idomeneus – Cretan warrior, priest of Leitus.

Kylix – A boy, slave of Hipponax.

Leukas – Alban sailor, later deck master on Lydia. Kelt of the Dumnones of Briton.

Miltiades – Tyrant of the Thracian Chersonese. His son, Cimon or Kimon, rose to be a great man in Athenian politics. Probably the author of the Athenian victory of Marathon, Miltiades was a complex man, a pirate, a warlord, and a supporter of Athenian democracy.

Penelope – Daughter of Chalkeotechnes, sister of Arimnestos.

Polymarchos – ex-slave swordmaster of Syracusa.

Phrynicus – Ancient Athenian playwright and warrior.

Sappho – A Greek poetess from the island of Lesbos, born sometime around 630 BC and died between 570 and 550 BC. Her father was probably Lord of Eressos. Widely considered the greatest lyric poet of Ancient Greece.

Seckla – Numidian ex-slave.

Simonalkes – Head of the collateral branch of the Plataean Corvaxae, cousin to Arimnestos.

Simonides – Another great lyric poet, he lived c.556–468 BC, and his nephew, Bacchylides, was as famous as he. Perhaps best known for his epigrams, one of which is:

Ω ξεῖν’, ἀγγέλλειν Λακεδαιμονίοις ὅτι τῇδε κείμεθα, τοῖς κείνων ῥήμασι πειθόμενοι.

Go tell the Spartans, thou who passest by, That here, obedient to their laws, we lie.

Thales – c.624–c.546 BC The first philosopher of the Greek tradition, whose writings were still current in Arimnestos’s time. Thales used geometry to solve problems such as calculating the height of the pyramids in Aegypt and the distance of ships from the shore. He made at least one trip to Aegypt. He is widely accepted as the founder of western mathematics.

Themistocles – Leader of the demos party in Athens, father of the Athenian Fleet. Political enemy of Aristides.

Theognis – Theognis of Megara was almost certainly not one man but a whole canon of aristocratic poetry under that name, much of it practical. There are maxims, many very wise, laments on the decline of man and the age, and the woes of old age and poverty, songs for symposia, etc. In later sections there are songs and poems about homosexual love and laments for failed romances. Despite widespread attributions, there was, at some point, a real Theognis who may have lived in the mid-6th century BC, or just before the events of this series. His poetry would have been central to the world of Arimnestos’s mother.

Vasileos – master shipwright and helmsman.

If you all keep coming, night after night, my daughter will have the greatest wedding feast in the history of the Hellenes. Perhaps, should my sword-arm fail me, I can have an evening-star life as a rhapsode.

Heh. But the truth is, it’s the story, not the teller. Who would not want to hear the greatest story of the greatest war ever fought by men? And you expect me to say ‘since Troy’ and I answer – any soldier knows Troy was just one city. We fought the world, and we triumphed.

The first night, I told you of my youth, and how I went to Calchas the priest to be educated as a gentleman, and instead learned to be a spear fighter. Because Calchas was no empty windbag, but a Killer of Men, who had stood his ground many times in the storm of bronze. And veterans came from all over Greece to hang their shields for a time at our shrine and talk to Calchas, and he sent them away whole, or better men, at least. Except that the worst of them the Hero called for, and the priest would kill them on the precinct walls and send their shades shrieking to feed the old Hero, or serve him in Hades.

Mind you, friends, Leithos wasn’t some angry old god demanding blood sacrifice, but Plataea’s hero from the Trojan War. And he was a particularly Boeotian hero, because he was no great man-slayer, no tent-sulker. His claim to fame is that he went to Troy and fought all ten years. That on the day that mighty Hector raged by the ships of the Greeks and Achilles skulked in his tent, Leithos rallied the lesser men and formed a tight shield wall and held Hector long enough for Ajax and the other Greek heroes to rally.

You might hear a different story in Thebes, or Athens, or Sparta. But that’s the story of the Hero I grew to serve, and I spent years at his shrine, learning the war dances that we call the Pyricche. Oh, I learned to read old Theogonis and Hesiod and Homer, too. But it was the spear, the sword and the aspis that sang to me.

When my father found that I was learning to be a warrior and not a man of letters, he came and fetched me home, and old Calchas . . . died. Killed himself, more like. But I’ve told all this – and how little Plataea, our farm town at the edge of Boeotia, sought to be free of cursed Thebes and made an alliance with distant Athens. I told you all how godlike Miltiades came to our town and treated my father, the bronzesmith – and Draco the wheelwright and old Epiktetus the farmer – like Athenian gentlemen, how he wooed them with fine words and paid hard silver for their products, so that he bound them to his own political ends and to the needs of Athens.

When I was still a gangly boy – tall and well muscled, as I remember, but too young to fight in the phalanx – Athens called for little Plataea’s aid, and we marched over Kitharon, the ancient mountain that is also our glowering god, and we rallied to the Athenians at Oinoe. We stood beside them against Sparta and Corinth and all the Peloponnesian cities – and we beat them.

Well – Athens beat them. Plataea barely survived, and my older brother, who should have been my father’s heir, died there with a Spartiate’s spear in his belly.

Four days later, when we fought again – this time against Thebes – I was in the phalanx. Again, we triumphed. And I was a hoplite.

And two days later, when we faced the Euboeans, I saw my cousin Simon kill my father, stabbing him in the back under his bright bronze cuirass. When I fell over my father’s corpse, I took a mighty blow, and when I awoke, I had no memory of Simon’s treachery.

When I awoke, of course, I was a slave. Simon had sold me to Phoenician traders, and I went east with a cargo of Greek slaves.

I was a slave for some years – and in truth, it was not a bad life. I went to a fine house, ruled by rich, elegant, excellent people – Hipponax the poet and his wife and two children. Archilogos – the elder boy – was my real master, and yet my friend and ally, and we had many escapades together. And his sister, Briseis—

Ah, Briseis. Helen, returned to life.

We lived in far-off Ephesus, one of the most beautiful and powerful cities in the Greek world – yet located on the coast of Asia. Greeks have lived there since the Trojan War, and the temple of Artemis there is one of the wonders of the world. My master went to school each day at the temple for Artemis, and there the great philosopher, Heraklitus, had his school, and he would shower us with questions every bit as painful as the blows of the old fighter who taught us pankration at the gymnasium.

Heraklitus. I have met men – and women – who saw him as a charlatan, a dreamer, a mouther of impieties. In fact, he was deeply religious – his family held the hereditary priesthood of Artemis – but he believed that fire was the only true element, and change the only constant. I can witness both.

It was a fine life. I got a rich lord’s education for nothing. I learned to drive a chariot, and to ride a horse and to fight and to use my mind like a sword. I loved it all, but best of all—

Best of all, I loved Briseis.

And while I loved her – and half a dozen other young women – I grew to manhood listening to Greeks and Persians plotting various plots in my master’s house, and one night all the plots burst forth into ugly blossoms and bore the fruit of red-handed war, and the Greek cities of Ionia revolted against the Persian overlords.

Now, as tonight’s story will be about war with the Persians, let me take a moment to remind you of the roots of the conflict. Because they are ignoble, and the Greeks were no better than the Persians, and perhaps a great deal worse. The Ionians had money, power and freedom – freedom to worship, freedom to rule themselves – under the Great King, and all it cost them was taxes and the ‘slavery’ of having to obey the Great King in matters of foreign policy. The ‘yoke’ of the Persians was light and easy to wear, and no man alive knows that better than me, because I served – as a slave – as a herald between my master and the mighty Artapherenes, the satrap of all Phrygia. I knew him well – I ran his errands, dressed him at times, and one dark night, when my master Hipponax caught the Persian in his wife’s bed, I saved his life when my master would have killed him. I saved my master’s life, as well, holding the corridor against four Persian soldiers of high repute – Aryanam, Pharnakes, Cyrus and Darius. I know their names because they were my friends, in other times.

And you’ll hear of them again. Except Pharnakes, who died in the Bosporus, fighting Carians.

At any rate, after that night of swords and fire and hate, my master went from being a loyal servant of Persia to a hate-filled Greek ‘patriot’. And our city – Ephesus – roused itself to war. And amidst it all, my beloved Briseis lost her fiancé to rumour and innuendo, and Archilogos and I beat him for his impudence. I had learned to kill, and to use violence to get what I wanted. And as a reward, I got Briseis – or to be more accurate, she had me. My master freed me, not knowing that I had just deflowered his daughter, and I sailed away with Archilogos to avoid the wrath of the suitor’s relatives.

We joined the Greek revolt at Lesvos, and there, on the beach, I met Aristides – sometimes called the Just, one of the greatest heroes of Athens, and Miltiades’ political foe.

That was the beginning of my true life. My life as a man of war. I won my first games on a beach in Chios and I earned my first suit of armour, and I went to war against the Persians.

But the God of War, Ares, was not so much in charge of my life as Aphrodite, and when we returned to Ephesus to plan the great war, I spent every hour that I could with Briseis, and the result – I think now – was never in doubt. But Heraklitus, the great sage, asked me to swear an oath to all the gods that I would protect Archilogos and his family – and I swore. Like the heroes in the old stories, I never thought about the consequence of swearing such a great oath and sleeping all the while with Briseis.

Ah, Briseis! She taunted me with cowardice when I stayed away from her and devoured me when I visited her, s

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...