- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

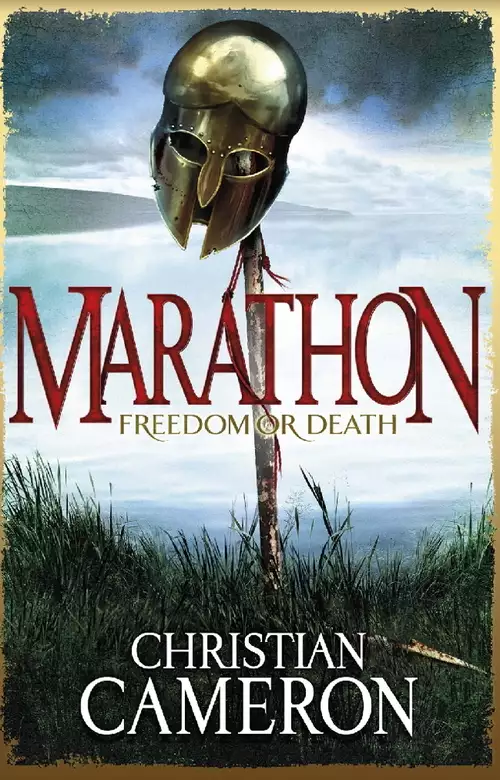

Synopsis

Two and a half thousand years ago, the Greeks and the Persians fought an epic battle to decide the future of the world....

Arimnestos of Plataea grew up wanting to be a bronzesmith, like his father. Then, in the chaos of war, he was taken to a city in the Persian empire and sold as a slave. To win his freedom he had to show that he could fight and kill. Now, to preserve that freedom, he must kill again.

For the Persians are coming. A vast army sent by King Darius to put down the rebellious Greeks and burn the city of Athens to the ground. Standing against them on the plain of Marathon is a much smaller force of Athenians, alongside their Plataean allies. To defeat such overwhelming force seems impossible. And yet to yield would mean the destruction of everything the Greeks have dreamed of.

In the dust and heat of Marathon, in the clash of shields and the rush of spears, amid the thunder of hooves and the screams of the dying, those dreams will undergo their fiercest test — and Arimnestos and his Greek comrades will discover the true price of freedom.

Release date: August 18, 2011

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Marathon

Christian Cameron

I am an amateur Greek scholar. My definitions are my own, but taken from the LSJ or Routeledge’s Handbook of Greek Mythology or Smith’s Classical

Dictionary. On some military issues I have the temerity to disagree with the received wisdom on the subject. Also check my website at www.hippeis.com for more information and some helpful

pictures.

Akinakes A Scythian short sword or long knife, also sometimes carried by Medes and Persians.

Andron The ‘men’s room’ of a proper Greek house – where men have symposia. Recent research has cast real doubt as to the sexual exclusivity of the

room, but the name sticks.

Apobatai The Chariot Warriors. In many towns, towns that hadn’t used chariots in warfare for centuries, the Apobatai were the elite three hundred or so. In

Athens, they competed in special events; in Thebes, they may have been the forerunners of the Sacred Band.

Archon A city’s senior official or, in some cases, one of three or four. A magnate.

Aspis The Greek hoplite’s shield (which is not called a hoplon!). The aspis is about a yard in diameter, is deeply dished (up to six inches deep) and should

weigh between eight and sixteen pounds.

Basileus An aristocratic title from a bygone era (at least in 500 BC) that means ‘king’ or ‘lord’.

Bireme A warship rowed by two tiers of oars, as opposed to a trireme, which has three tiers.

Chiton The standard tunic for most men, made by taking a single continuous piece of cloth and folding it in half, pinning the shoulders and open side. Can be made quite

fitted by means of pleating. Often made of very fine quality material – usually wool, sometimes linen, especially in the upper classes. A full chiton was ankle length for men and

women.

Chitoniskos A small chiton, usually just longer than modesty demanded – or not as long as modern modesty would demand! Worn by warriors and farmers, often

heavily bloused and very full by warriors to pad their armour. Usually wool.

Chlamys A short cloak made from a rectangle of cloth roughly 60 by 90 inches – could also be worn as a chiton if folded and pinned a different way. Or slept

under as a blanket.

Corslet/Thorax In 500 BC, the best corslets were made of bronze, mostly of the so-called ‘bell’ thorax variety. A few

muscle corslets appear at the end of this period, gaining popularity into the 450s. Another style is the ‘white’ corslet, seen to appear just as the Persian Wars begin

– reenactors call this the ‘Tube and Yoke’ corslet, and some people call it (erroneously) the linothorax. Some of them may have been made of linen –

we’ll never know – but the likelier material is Athenian leather, which was often tanned and finished with alum, thus being bright white. Yet another style was a tube and yoke of scale,

which you can see the author wearing on his website. A scale corslet would have been the most expensive of all, and probably provided the best protection.

Daidala Cithaeron, the mountain that towered over Plataea, was the site of a remarkable fire-festival, the Daidala, which was celebrated by the Plataeans on the

summit of the mountain. In the usual ceremony, as mounted by the Plataeans in every seventh year, a wooden idol (daidalon) would be dressed in bridal robes and dragged on an ox-cart from

Plataea to the top of the mountain, where it would be burned after appropriate rituals. Or, in the Great Daidala, which were celebrated every forty-nine years, fourteen daidala from

different Boeotian towns would be burned on a large wooden pyre heaped with brushwood, together with a cow and a bull that were sacrificed to Zeus and Hera. This huge pyre on the mountain top must

have provided a most impressive spectacle; Pausanias remarks that he knew of no other flame that rose as high or could be seen from so far.

The cultic legend that was offered to account for the festival ran as follows. When Hera had once quarrelled with Zeus, as she often did, she had withdrawn to her childhood home of Euboea

and had refused every attempt at reconciliation. So Zeus sought the advice of the wisest man on earth, Cithaeron (the eponym of the mountain), who ruled at Plataea in the earliest times.

Cithaeron advised him to make a wooden image of a woman, to veil it in the manner of a bride, and then to have it drawn along in an ox-cart after spreading the rumour that he was planning to

marry the nymph Plataea, a daughter of the river god Asopus. When Hera rushed to the scene and tore away the veils, she was so relieved to find a wooden effigy rather than the expected bride

that she at last consented to be reconciled with Zeus. (Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology, pp. 137–8)

Daimon Literally a spirit, the daimon of combat might be adrenaline, and the daimon of philosophy might simply be native intelligence. Suffice it to say that

very intelligent men – like Socrates – believed that godsent spirits could infuse a man and influence his actions.

Daktyloi Literally digits or fingers, in common talk ‘inches’ in the system of measurement. Systems differed from city to city. I have taken the liberty of using

just the Athenian units.

Despoina Lady. A term of formal address.

Diekplous A complex naval tactic about which some debate remains. In this book, the Diekplous, or through stroke, is commenced with an attack by the ramming

ship’s bow (picture the two ships approaching bow to bow or head on) and cathead on the enemy oars. Oars were the most vulnerable part of a fighting ship, something very difficult to imagine

unless you’ve rowed in a big boat and understand how lethal your own oars can be – to you! After the attacker crushes the enemy’s oars, he passes, flank to flank, and then turns

when astern, coming up easily (the defender is almost dead in the water) and ramming the enemy under the stern or counter as desired.

Doru A spear, about ten feet long, with a bronze butt-spike.

Eleutheria Freedom.

Ephebe A young, free man of property. A young man in training to be a hoplite. Usually performing service to his city and, in ancient terms, at one of the two peaks

of male beauty.

Eromenos The ‘beloved’ in a same-sex pair in ancient Greece. Usually younger, about seventeen. This is a complex, almost dangerous subject in the modern world

– were these pair-bonds about sex, or chivalric love, or just a ‘brotherhood’ of warriors? I suspect there were elements of all three. And to write about this period without

discussing the eromenos/erastes bond would, I fear, be like putting all the warriors in steel armour instead of bronze . . .

Erastes The ‘lover’ in a same-sex pair bond – the older man, a tried warrior, twenty-five to thirty years old.

Eudaimonia Literally ‘well-spirited’. A feeling of extreme joy.

Exhedra The porch of the women’s quarters – in some cases, any porch over a farm’s central courtyard.

Helots The ‘race of slaves’ of Ancient Sparta – the conquered peoples who lived with the Spartiates and did all of their work so that they could

concentrate entirely on making war and more Spartans.

Hetaira Literally a ‘female companion’. In ancient Athens, a hetaira was a courtesan, a highly skilled woman who provided sexual companionship as well as

fashion, political advice and music.

Himation A very large piece of rich, often embroidered wool, worn as an outer garment by wealthy citizen women or as a sole garment by older men, especially those in

authority.

Hoplite A Greek upper-class warrior. Possession of a heavy spear, a helmet and an aspis (see above) and income above the marginal lowest free class were all required

to serve as a hoplite. Although much is made of the ‘citizen soldier’ of ancient Greece, it would be fairer to compare hoplites to medieval knights than to Roman

legionnaires or modern National Guardsmen. Poorer citizens did serve, and sometimes as hoplites or marines, but in general, the front ranks were the preserve of upper-class men who could

afford the best training and the essential armour.

Hoplitodromos The hoplite race, or race in armour. Two stades with an aspis on your shoulder, a helmet and greaves in the early runs. I’ve run

this race in armour. It is no picnic.

Hoplomachia A hoplite contest, or sparring match. Again, there is enormous debate as to when hoplomachia came into existence and how much training Greek

hoplites received. One thing that they didn’t do is drill like modern soldiers – there’s no mention of it in all of Greek literature. However, they had highly evolved

martial arts (see pankration) and it is almost certain that hoplomachia was a term that referred to ‘the martial art of fighting when fully equipped as a

hoplite’.

Hoplomachos A participant in hoplomachia.

Hypaspist Literally ‘under the shield’. A squire or military servant – by the time of Arimnestos, the hypaspist was usually a younger man of the

same class as the hoplite.

Kithara A stringed instrument of some complexity, with a hollow body as a soundboard.

Kline A couch.

Kopis The heavy, back-curved sabre of the Greeks. Like a longer, heavier modern kukri or Gurkha knife.

Kore A maiden or daughter.

Kylix A wide, shallow, handled bowl for drinking wine.

Logos Literally ‘word’. In pre-Socratic Greek philosophy the word is everything – the power beyond the gods.

Longche A six to seven foot throwing spear, also used for hunting. A hoplite might carry a pair of longchai, or a single, longer and heavier doru.

Machaira A heavy sword or long knife.

Maenads The ‘raving ones’ – ecstatic female followers of Dionysus.

Mastos A woman’s breast. A mastos cup is shaped like a woman’s breast with a rattle in the nipple – so when you drink, you lick the nipple and the

rattle shows that you emptied the cup. I’ll leave the rest to imagination . . .

Medimnos A grain measure. Very roughly – 35 to 100 pounds of grain.

Megaron A style of building with a roofed porch.

Navarch An admiral.

Oikia The household – all the family and all the slaves, and sometimes the animals and the farmland itself.

Opson Whatever spread, dip or accompaniment an ancient Greek had with bread.

Pais A child.

Palaestra The exercise sands of the gymnasium.

Pankration The military martial art of the ancient Greeks – an unarmed combat system that bears more than a passing resemblance to modern MMA techniques, with a series

of carefully structured blows and domination holds that is, by modern standards, very advanced. Also the basis of the Greek sword and spear-based martial arts. Kicking, punching, wrestling,

grappling, on the ground and standing, were all permitted.

Peplos A short over-fold of cloth that women could wear as a hood or to cover the breasts.

Phalanx The full military potential of a town; the actual, formed body of men before a battle (all of the smaller groups formed together made a phalanx). In this

period, it would be a mistake to imagine a carefully drilled military machine.

Phylarch A file-leader – an officer commanding the four to sixteen men standing behind him in the phalanx.

Polemarch The war leader.

Polis The city. The basis of all Greek political thought and expression, the government that was held to be more important – a higher god – than any individual

or even family. To this day, when we talk about politics, we’re talking about the ‘things of our city’.

Porne A prostitute.

Porpax The bronze or leather band that encloses the forearm on a Greek aspis.

Psiloi Light infantrymen – usually slaves or adolescent freemen who, in this period, were not organised and seldom had any weapon beyond some rocks to throw.

Pyrrhiche The ‘War Dance’. A line dance in armour done by all of the warriors, often very complex. There’s reason to believe that the Pyrrhiche was

the method by which the young were trained in basic martial arts and by which ‘drill’ was inculcated.

Pyxis A box, often circular, turned from wood or made of metal.

Rhapsode A master-poet, often a performer who told epic works like the Iliad from memory.

Satrap A Persian ruler of a province of the Persian Empire.

Skeuophoros Literally a ‘shield carrier’, unlike the hypaspist, this is a slave or freed man who does camp work and carries the armour and baggage.

Sparabara The large wicker shield of the Persian and Mede elite infantry. Also the name of those soldiers.

Spolas Another name for a leather corslet, often used for the lion skin of Heracles.

Stade A measure of distance. An Athenian stade is about 185 metres.

Strategos In Athens, the commander of one of the ten military tribes. Elsewhere, any senior Greek officer – sometimes the commanding general.

Synaspismos The closest order that hoplites could form – so close that the shields overlap, hence ‘shield on shield’.

Taxis Any group but, in military terms, a company; I use it for 60 to 300 men.

Thetes The lowest free class – citizens with limited rights.

Thorax See corslet.

Thugater Daughter. Look at the word carefully and you’ll see the ‘daughter’ in it . . .

Triakonter A small rowed galley of thirty oars.

Trierarch The captain of a ship – sometimes just the owner or builder, sometimes the fighting captain.

Zone A belt, often just rope or finely wrought cord, but could be a heavy bronze kidney belt for war.

General Note on Names and Personages

This series is set in the very dawn of the so-called Classical Era, often measured from the Battle of Marathon (490 BC). Some, if not most, of the

famous names of this era are characters in this series – and that’s not happenstance. Athens of this period is as magical, in many ways, as Tolkien’s Gondor, and even the quickest

list of artists, poets, and soldiers of this era reads like a ‘who’s who’ of western civilization. Nor is the author tossing them together by happenstance – these people

were almost all aristocrats, men (and women) who knew each other well – and might be adversaries or friends in need. Names in bold are historical characters – yes, even Arimnestos

– and you can get a glimpse into their lives by looking at Wikipedia or Britannia online. For more in-depth information, I recommend Plutarch and Herodotus, to whom I owe a great deal.

Arimnestos of Plataea may – just may – have been Herodotus’s source for the events of the Persian Wars. The careful reader will note that

Herodotus himself – a scribe from Halicarnassus – appears several times . . .

Archilogos – Ephesian, son of Hipponax the poet; a typical Ionian aristocrat, who loves Persian culture and Greek culture too, who serves his city, not some cause of

‘Greece’ or ‘Hellas’, and who finds the rule of the Great King fairer and more ‘democratic’ than the rule of a Greek tyrant.

Arimnestos – Child of Chalkeotechnes and Euthalia.

Aristagoras – Son of Molpagoras, nephew of Histiaeus. Aristagoras led Miletus while Histiaeus was a virtual prisoner of the Great King Darius at Susa. Aristagoras

seems to have initiated the Ionian Revolt – and later to have regretted it.

Aristides – Son of Lysimachus, lived roughly 525–468 BC, known later in life as ‘The Just’. Perhaps best known as one of the

commanders at Marathon. Usually sided with the Aristocratic party.

Artaphernes – Brother of Darius, Great King of Persia, and Satrap of Sardis. A senior Persian with powerful connections.

Bion – A slave name, meaning ‘life’. The most loyal family retainer of the Corvaxae.

Briseis – Daughter of Hipponax, sister of Archilogos.

Calchas – A former warrior, now the keeper of the shrine of the Plataean Hero of Troy, Leitos.

Chalkeotechnes – The Smith of Plataea; head of the family Corvaxae, who claim descent from Heracles.

Chalkidis – Brother of Arimnestos, son of Chalkeotechnes.

Darius – King of Kings, the lord of the Persian Empire, brother to Artaphernes.

Draco – Wheelwright and wagon builder of Plataea, a leading man of the town.

Empedocles – A priest of Hephaestus, the Smith God.

Epaphroditos – A warrior, an aristocrat of Lesbos.

Eualcidas – A Hero. Eualcidas is typical of a class of aristocratic men – professional warriors, adventurers, occasionally pirates or merchants by turns. From

Euboea.

Heraclitus – c.535–475 BC. One of the ancient world’s most famous philosophers. Born to an aristocratic family, he chose

philosophy over political power. Perhaps most famous for his statement about time: ‘You cannot step twice into the same river’. His belief that ‘strife is justice’ and other

similar sayings which you’ll find scattered through these pages made him a favourite with Nietzsche. His works, mostly now lost, probably established the later philosophy of Stoicism.

Herakleides – An Aeolian, a Greek of Asia Minor. With his brothers Nestor and Orestes, he becomes a retainer – a warrior – in service to Arimnestos. It is easy,

when looking at the birth of Greek democracy, to see the whole form of modern government firmly established – but at the time of this book, democracy was less than skin deep and most armies

were formed of semi-feudal war bands following an aristocrat.

Heraklides – Aristides’ helmsman, a lower-class Athenian who has made a name for himself in war.

Hermogenes – Son of Bion, Arimnestos’s slave.

Hesiod – A great poet (or a great tradition of poetry) from Boeotia in Greece, Hesiod’s ‘Works and Days’ and ‘Theogony’ were widely read

in the sixth century and remain fresh today – they are the chief source we have on Greek farming, and this book owes an enormous debt to them.

Hippias – Last tyrant of Athens, overthrown around 510 BC (that is, just around the beginning of this series), Hippias escaped into exile and became a pensioner of

Darius of Persia.

Hipponax – 540–c.498 BC. A Greek poet and satirist, considered the inventor of parody. He is supposed to have said ‘There

are two days when a woman is a pleasure: the day one marries her and the day one buries her’.

Histiaeus – Tyrant of Miletus and ally of Darius of Persia, possible originator of the plan for the Ionian Revolt.

Homer – Another great poet, roughly Hesiod’s contemporary (give or take fifty years) and again, possibly more a poetic tradition than an individual man. Homer is

reputed as the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, two great epic poems which, between them, largely defined what heroism and aristocratic good behaviour should be in Greek society

– and, you might say, to this very day.

Kylix – A boy, slave of Hipponax.

Miltiades – Tyrant of the Thracian Chersonese. His son, Cimon or Kimon, rose to be a great man in Athenian politics. Probably the author of the Athenian victory of

Marathon, Miltiades was a complex man, a pirate, a warlord and a supporter of Athenian democracy.

Penelope – Daughter of Chalkeotechnes, sister of Arimnestos.

Sappho – A Greek poetess from the island of Lesbos, born sometime around 630 BC and died between 570 and 550 BC. Her

father was probably Lord of Eresus. Widely considered the greatest lyric poet of Ancient Greece.

Simonalkes – Head of the collateral branch of the Plataean Corvaxae, cousin to Arimnestos.

Simonides – Another great lyric poet, he lived c.556–468 BC, and his nephew, Bacchylides, was as famous as he. Perhaps best known

for his epigrams, one of which is:

Go tell the Spartans, thou who passest by,

That here, obedient to their laws, we lie.

Thales – c.624–c.546 BC The first philosopher of the Greek tradition, whose writings were still current in

Arimnestos’s time. Thales used geometry to solve problems such as calculating the height of the pyramids in Aegypt and the distance of ships from the shore. He made at least one trip to

Aegypt. He is widely accepted as the founder of western mathematics.

Theognis – Theognis of Megara was almost certainly not one man but a whole canon of aristocratic poetry under that name, much of it practical. There are maxims, many

very wise, laments on the decline of man and the age, and the woes of old age and poverty, songs for symposia, etc. In later sections there are songs and poems about homosexual love and laments for

failed romances. Despite widespread attributions, there was, at some point, a real Theognis who may have lived in the mid-6th century BC, or just before the events of this

series. His poetry would have been central to the world of Arimnestos’s mother.

I’m not any younger, and that’s a fact. But I gather my story’s a good one. Or you young people wouldn’t cluster around so

eagerly to hear my tale.

Honey, you’ve brought your scribbler back to me. He’s promised to write it all out in the new way, although if I was allowed, I’d rather hear a rhapsode sing it the old

way. But the old ways died with the Medes, didn’t they? It’s all different now. The world I’m telling you about is as dead as old Homer’s heroes at Troy. Even my

thugater here thinks I’m the relic of a time when the gods still walked abroad. Eh?

You young people make me laugh. You’re soft. But you’re soft because we killed all the monsters. And whose fault is that?

And the blushing girl’s come back – ah, it makes me younger just to see you, child. I’d take you myself, but all my other wives would object. Hah! Look at that colour on her

face, my young friends. There’s fire under that skin. Marry her quick, before the fire catches somewhere it oughtn’t.

It looks to me as if my daughter has brought every young sprig in the town, and some foreigners from up the coast as well, just to hear her old man speak of his fate. Flattering in a way –

but you know that I’ll tell you of Marathon. And you know that there is no nobler moment in all the history of men – of Hellenes. We stood against them, man to man, and we were

better.

But it didn’t start that way, not by as long a ride as a man could make in a year on a good horse.

For those of you who missed the first nights of my rambling story, I’m Arimnestos of Plataea. I told the story of how my father was the bronze-smith of our city, and how we marched to

fight the Spartans at Oinoe, and fought three battles in a week. How he was murdered by his cousin Simon. How Simon sold me as a slave, far to the east among the men of Ionia, and how I grew to

manhood as a slave in the house of a fine poet in Ephesus, one of the greatest cities in the world, right under the shadow of the Temple of Artemis. I was slave to Hipponax the poet and his son

Archilogos. In time they freed me. I became a warrior, and then a great warrior, but when the Long War began – the war between the Medes and the Greeks – I served with the Athenians at

Sardis.

Why, you might ask. My thugater will groan to hear me tell this again, but I loved Briseis. Indeed, to say I loved her – Hipponax’s dark-haired daughter, Artemis’s avatar and

perhaps Aphrodite’s as well, Helen returned to earth – well, to say I loved her is to say nothing. As you will hear, if you stay to listen.

Briseis wasn’t the only person I loved in Ephesus. I loved Archilogos – the true friend of my youth. We were well matched in everything. I was his companion, first as a slave, and

then free – and we competed. At everything. And I also loved Heraclitus, the greatest philosopher of his day. To me, the greatest ever, almost like a god in his wisdom. He, and he alone, kept

me from growing to manhood as a pure killer. He gave me advice which I ignored – but which stayed in my head. To this day, in fact. He taught me that the river of our lives flows on and on

and can never be reclaimed. Later, I knew that he’d tried to keep me from Briseis.

When her father caught us together, it was the end of my youth. I was cast out of the household, and that’s why I was with the Athenians at Sardis, and not in the phalanx of the men of

Ephesus to save Hipponax when the Medes gave him his mortal wound.

I found him screaming on the battlefield, and I sent him on the last journey because I loved him, even though he had been my owner. It was done with love, but his son, Archilogos, did not see it

that way, and we became foes.

I spent the next years of the Ionian Revolt – the first years of the Long War – gaining word-fame with every blow I struck. I should blush to tell it – but why? When I served

at Sardis, I was a man that other men would trust at their side in the phalanx. By the time I led my ship into the Persians at the big fight at Cyprus, I was a warrior that other men feared in the

storm of bronze.

The Greeks won the sea-fight but lost on land, that day at Cyprus. And the back of the revolt should have been broken, but it was not. We retreated to Chios and Lesbos, and I joined Miltiades of

Athens – a great aristocrat, and a great pirate – and we got new allies, and the fighting switched to the Chersonese – the land of the Trojan War. We fought the Medes by sea and

land. Sometimes we bested them. Miltiades made money and so did I. I owned my own ship, and I was rich.

I killed many men.

And then we faced the Medes in Thrace – just a few ships from each side. By then, Briseis had married the most powerful man in the Greek revolt – and had found him a broken reed. We

beat the Persians and their Thracian allies and I killed her husband, even though he was supposedly on my side. I laugh even now – that was a good killing, and I spit on his shade.

But she didn’t want me, except in her bed and in her thoughts. Briseis loved me as I loved her – but she meant to be Queen of the Ionians, not a pirate’s trull, and all I was

in those years was a bloodyhanded pirate.

Fair enough. But it shattered me for a while.

I left Thrace and I left Miltiades, and I went home to Plataea. Where the man who had killed my father and married my mother was lording it over the family farm.

Simon, and his four sons. My cousins.

Your cousins too, thugater. Simon was a wreck of a man and a coward, but I’d not say the same of his get. They were tough bastards. I didn’t hack him down. I went to the assembly, as

my master Heraclitus would have wanted me to do.

The law killed old Simon the coward, but his sons wanted revenge.

And the Persians were determined to finish off the Ionians and put the Greeks under their heel.

And Briseis kept marrying great men, and finding them wanting.

The world, you know, is shaped like the bowl of an aspis. Out on the rim flows the edge of the river-sea that circles all, and up where the porpax binds a man’s arm is the

sun and the moon, and the great circle of earth fills all between. Medes and Persians, Scythians and Greeks and Ionians and Aeolians and Italians and Aethiopians and Aegyptians and Africans and

Lydians and Phrygians and Carians and Celts and Phoenicians and the gods know who else fill the bowl of the aspis from rim to rim. And in those days, as the Long War began to take hold like a

new-started fire on dry kindling, you could hear men talking of war, making war, killing, dying, making weapons and training in their use, all across the bowl of that aspis from rim to rim, until

the murmur of the bronze-clad god’s chorus filled the world.

It was the sixth year of the Long War, and Hipparchus was archon in Athens, and Myron was archon for his second term in Plataea. Tisikrites of Croton won the stade sprint at Olympia. The weather

was good, the crops were rolling in.

I thought I might settle down and make myself a bronze-smith and a farmer, like my father before me.

Ares must have laughed.

1

Shield up.

Thrust overhand.

Turn – catch the spear on the rim of my shield, pivot on my toes and thrust at my opponent.

He catches my spear on his shield and grins. I can see the flash of his grin in the tau of his Corinthian helmet’s faceplate. Then his plumes nod as he turns his head – checks

the man behind him.

I thrust overhand, hard.

He catches my blow, pivots on the balls of his feet and steps back with his shield facing me.

His file-mate pushes past him, a heavy overhand blow driving me back half a step.

The music rises, the aulos pipe sounding faster, the drums beating the rhythm like the sound of marching feet.

I sidestep, faster, and my shield rim flashes like a live thing. My black spear is an iron-tipped tongue of death in my strong right hand and I am one with the men to the right and left, the men

behind. I am not Arimnestos the killer of men. I am only one Plataean, and together, we are this.

‘Plataeans!’ I roar.

I plant my right foot. Every man in the front rank does the same, and the pipes howl, and every man crouches, screams and pushes forward, and three hundred voices call: The Ravens of

Apollo! The roar shakes the walls and echoes from the Temple of Hera.

The music falls silent, and after a pause the whole assembly – all the free men and women, the slaves, the freedmen – erupt in applause.

Under my armour, I am covered in sweat.

Hermogenes – my opponent – puts his arms around me. ‘That was . . .’

There are no words to describe how good that was. We danced the Pyrrhiche, the war dance, with the picked three hundred men of Plataea, and Ares himself must have watched us.

Older men – the archon, the lawmakers – clasp my hand. My back is slapped so often that I worry they are pulling the laces on my scale armour.

Good to have you back, they all say.

I am happy.

Ting-ting.

Ting-ting.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...