- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

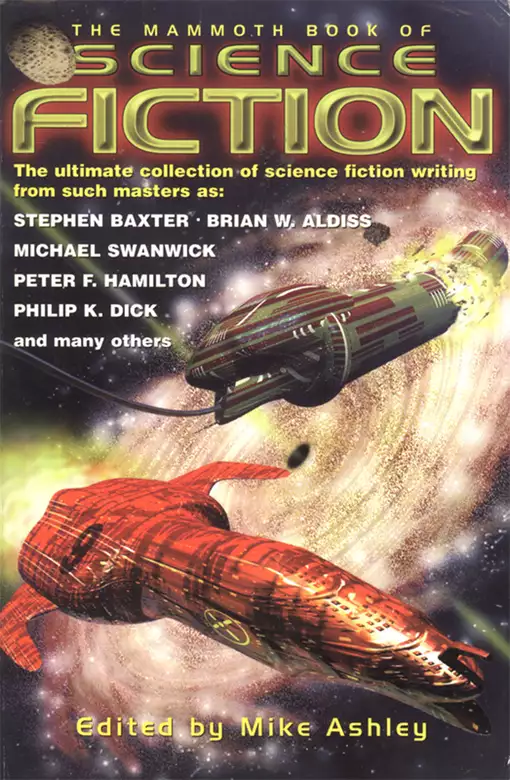

The art of writing great science fiction is that it challenges the imagination, pushing it to extreme limits and in this anthology, selecting some of the best modern science fiction from the last fifty years, twenty leading authors of the genre ask the question 'What if...?' and then give their own very personal views of the changes and surprises which may befall humanity in the centuries to come. In Ulla, Ulla Eric Brown recounts the first manned Martian expedition and discovers that H. G. Wells may have been right after all. In The Infinite Assassin Greg Egan polices the dimensions, seeking those who are taking over their alternate selves. Geoffrey A. Landis takes us into the depths of a black hole in Approaching Perimelasma. Is the ultimate Utopia heaven or hell? Robert Sheckley finds out in the classic A Ticket to Tranai. These and other stories by James White, Eric Frank Russell, Robert Reed, H. Beam Piper and H. Chandler Elliot make this one of the most entertaining and thought-provoking science fiction anthologies in lightyears.

Release date: November 28, 2013

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Science Fiction

Mike Ashley

Also available

The Mammoth Book of Arthurian Legends

The Mammoth Book of Awesome Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Battles

The Mammoth Book of Best New Erotica

The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror 2000

The Mammoth Book of Best New Science Fiction 14

The Mammoth Book of Bridge

The Mammoth Book of British Kings & Queens

The Mammoth Book of Cats

The Mammoth Book of Chess

The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Dogs

The Mammoth Book of Endurance and Adventure

The Mammoth Book of Erotica (New Edition)

The Mammoth Book of Erotic Photography

The Mammoth Book of Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Gay Erotica

The Mammoth Book of Great Detective Stories

The Mammoth Book of Gay Short Stories

The Mammoth Book of Haunted House Stories

The Mammoth Book of Hearts of Oak

The Mammoth Book of Historical Erotica

The Mammoth Book of Historical Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened in Britain

The Mammoth Book of International Erotica

The Mammoth Book of Jack the Ripper

The Mammoth Book of Jokes

The Mammoth Book of Legal Thrillers

The Mammoth Book of Lesbian Erotica

The Mammoth Book of Lesbian Short Stories

The Mammoth Book of Life Before the Mast

The Mammoth Book of Locked-Room Mysteries and Impossible Crimes

The Mammoth Book of Men O’War

The Mammoth Book of Murder

The Mammoth Book of Murder and Science

The Mammoth Book of New Erotica

The Mammoth Book of New Sherlock Holmes Adventures

The Mammoth Book of Private Lives

The Mammoth Book of Pulp Action

The Mammoth Book of Puzzles

The Mammoth Book of SAS & Elite Forces

The Mammoth Book of Seriously Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Sex, Drugs & Rock ’n’ Roll

The Mammoth Book of Short Erotic Novels

The Mammoth Book of Soldiers at War

The Mammoth Book of Sword & Honour

The Mammoth Book of the Edge

The Mammoth Book of The West

The Mammoth Book of True Crime (New Edition)

The Mammoth Book of True War Stories

The Mammoth Book of UFOs

The Mammoth Book of Unsolved Crimes

The Mammoth Book of Vampire Stories by Women

The Mammoth Book of War Correspondents

The Mammoth Book of Women Who Kill

The Mammoth Book of the World’s Greatest Chess Games

The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Unsolved Mysteries

All of the stories are copyright in the name of the individual authors or their estates as follows. Every effort has been made to trace the holders of copyright. In the event of any inadvertent transgression of copyright the editor would like to hear from the author or their representative via the publisher.

“Shards” © 1962 by Brian W. Aldiss. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, April 1962. Reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Curtis Brown Group Limited, London.

“Refugium” © 2002 by Stephen Baxter. First publication, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“Ulla, Ulla” © 2002 by Eric Brown. First publication, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“What Have I Done?” © 1952 by Mark Clifton. First published in Astounding SF, May 1952. Reprinted by permission of Barry N. Malzberg on behalf of the author’s estate.

“The Exit Door Leads In” © 1979 by Philip K. Dick. First published in The Rolling Stone College Papers, Fall 1979. Reprinted by permission of The Wylie Agency, Inc. New York. All rights reserved.

“The Infinite Assassin” © 1991 by Greg Egan. First published in Interzone, June 1991. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Inanimate Objection” © 1954 by H. Chandler Elliott. First published in Galaxy, February 1954. Unable to trace the author’s estate.

“Deathday” © 1991 by Peter F. Hamilton. First published in Fear! February 1991. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Pen and the Dark” © 1966 by Colin Kapp. First published in New Writings in SF #8 edited by John Carnell (London: Dobson, 1966). Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“Anachron” © 1953 by Damon Knight. First published in If, January 1954. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“Approaching Perimelasma” © 1997 by Geoffrey A. Landis. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, January 1998. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Except My Life3” © 1991 by John Morressy. First published in Amazing Stories, July 1991. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Finis” by Frank Lillie Pollock, first published in The Argosy, June 1906. Copyright expired in 1962.

“At the ‘Me’ Shop” © 1995 by Robert Reed. First published in Tomorrow SF, April 1995. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“High Eight” © 1965 by Keith Roberts. First published in New Writings in SF #4 edited by John Carnell (London: Dobson, 1965). Reprinted by permission of the Owlswick Literary Agency on behalf of the author’s estate.

“Vinland the Dream” © 1991 by Kim Stanley Robinson. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, November 1991. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Into Your Tent I’ll Creep” © 1957 by Eric Frank Russell. First published in Astounding SF, September 1957. Reprinted by permission of the Laurence Pollinger Literary Agency on behalf of the author’s estate.

“A Ticket to Tranai” © 1955 by Robert Sheckley. First published in Galaxy, October 1955. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“A Death in the House” © 1959 by Clifford D. Simak. First published in Galaxy, October 1959. Reprinted by permission of David W. Wixon on behalf of the author’s estate.

“The Very Pulse of The Machine” © 1998 by Michael Swanwick. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, February 1998. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Last Days of Earth” © 1901 by George C. Wallis. First published in The Harmsworth Magazine, July 1901. No surviving estate.

“Firewatch” © 1982 by Connie Willis. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, February 1982. Reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, the Lotts Agency, New York.

Science fiction has been called the literature of ideas, and it is certainly that. But it’s also something else. It’s about change – the changes arising from those ideas.

What fascinates me about science fiction (or “sf” as I tend to abbreviate it), and what draws me back to it time and again, is to see the wonder of human imagination about ourselves and the universe and to discover how each individual writer has used their skill, knowledge and, above all, imagination to develop an idea and see what it does. It’s the old question that provoked the study of science in the first place: “What if?” And the answer to that always results in change. It may be for good – one step onward; it may be for bad. A lot of sf serves as a warning to humanity about the perils of change.

You’ll find both kinds of stories here: those that take us one step forward – sometimes a whole load of steps forward – and those where we step backward. And there’s even a few where we step sideways.

There are stories set on other worlds, stories where beings from other worlds come to us; stories of robots and time travel and genetic engineering, and utopias, dystopias, impossible problems, catastrophes and ultimate apocalypses. All the stuff of science fiction. But above all they’re about people and how they have reacted to these discoveries, ideas and changes.

When I started to compile this anthology I wanted to select a wide range of the most intriguing and challenging science fiction published over the last forty or fifty years. Because science fiction deals with change and technology it is easy for some sf to date rapidly. Even the best written story, which was highly regarded fifty years ago, may not hold up well today because of the considerable changes that have affected science and society in the last twenty years. Science fiction may try and make predictions, but it’s seldom very good at it. Very few stories hit the mark as regards the Internet, for instance, or the rapid growth in mobile phones, in computers, in the fall of the communist Eastern bloc in Europe, the rise in the drug problem. So even when I revisited many of my favourite stories from years ago, they did not all stand up well today.

But I still achieved my aim. This anthology contains twenty-two stories. Two of them – by Stephen Baxter and Eric Brown – are brand new, written specially for this book. Another two – by Frank Lillie Pollock and George C. Wallis – are real “golden oldies” from a hundred years ago. The other eighteen stories are pretty much evenly selected from the 1950s and the 1990s with a smattering in between. The result is the best of the old and the best of the new, each one posing challenging and different ideas.

Suppose, for instance, we find a drug that allows you to access your other selves in other realities. How would you police that? That’s what Greg Egan tackles in “The Infinite Assassin”. What is reality and what is dream? Both Robert Reed and Kim Stanley Robinson approach that in very different ways. Are aliens already here and we just don’t realize it? See how H. Chandler Elliott and Mark Clifton deal with that. Can you really have an impenetrable object? That’s what Colin Kapp poses in “The Pen and the Dark”. Brian W. Aldiss and John Morressy, on the other hand, look at the effects and outcomes of genetic engineering, while Connie Willis considers just what else might have been helping us during the Second World War. And what would really happen if you entered a black hole? Geoffrey Landis takes us to the ultimate in “Approaching Perimelasma”.

There’s plenty more. If you want aliens, try the stories by Eric Brown, Peter Hamilton, Michael Swanwick and Clifford Simak. If you want a sardonic view of other societies, try Robert Sheckley and Philip K. Dick. And if you want the end of the world, try the two apocalyptic classics.

There should be something for everyone. Everything you could ever imagine is all just a step away. Have fun.

Mike Ashley

When Eric sent me this story I was delighted, because it was the ideal way to start this anthology – combining the old with the new. Eric Brown (b. 1960) emerged on the sf scene in 1987 with a series of inventive stories in Interzone that led to his first published collection The Time-Lapsed Man (1990). Other stories will be found in Blue Shifting (1995) whilst his novels include Meridian Days (1992), Engineman (1994), and the excellent Penumbra (1999). New York Nights (2000) marked the start of his Virex trilogy, SF thrillers set in 2040 featuring private eyes and virtual reality. The other titles are New York Blues and New York Dreams. You can find out more on his website < www.ericbrown.co.uk >.

After the debriefing, which lasted three days, Enright left the Kennedy Space Center and headed for home.

He drove south to the Keys in his ’08 Chevrolet convertible, taking his time now that he was alone for the first time in three years. For that long he had been cooped up in the Fortitude on its voyage to Mars and back. Even on the surface of the planet, beneath the immensity of the pink sky, he had never felt truly alone. Always there were the voices of McCarthy, Jeffries and Spirek on his com, and the prospect of the cramped living quarters on his return to the lander.

Ten kilometers south of Kennedy, on the coast road, he pulled into a parking lot overlooking the sea, climbed out and stared into the evening sky.

There was Mars, riding high overhead.

He considered the mission, but he had no original take on what they had discovered beneath the surface of the red planet. He was as baffled as everyone else. One thing he knew for certain, though: everything was different now. At some point, inevitably, the news would break, and things would change for ever.

He had been allowed a couple of hours with Delia after quarantine, before being whisked off to the intensive debriefing. Of course, he had not been cleared to discuss their findings with her, the one person in his life with whom he had shared everything. She had sensed something, though, detected in his manner that all was not right. She had been at mission control when the first broadcast came through from Mars, but Director Roberts had cut the transmission before anything major had leaked.

He shivered. The wind was turning cold.

He climbed back into his Chevrolet, reversed from the lot, and drove home.

He left the car in the drive and walked around the house.

The child’s swing, in situ when they had bought the place four years ago, had still not been removed. Delia had promised him that she would see to it while he was away.

She was sitting in the lighted conservatory, reading. She looked up as he pushed through the door, but made no move to rise and greet him.

“You weren’t due back until tomorrow,” she said, making it sound like an accusation.

“Let us off a day early. Thought I’d surprise you.” He was aware of the distance between them, after so long apart.

Over dinner, they chatted. Small talk, the inconsequential tone of which indicated that they both knew they were avoiding deeper issues. She was back teaching, three days a week at the local elementary school. Ted, her nephew, had been accepted at Florida State.

He wanted to tell her. He wanted to tell her everything that had happened on Mars. He had always shared everything with her in the past. So why not now?

Mission confidentiality? The papers he had signed seven years back on being accepted by NASA?

Or was it because what they had discovered might have been some kind of collective hallucination? And Delia might think that he was losing it, if he came out and told her?

A combination of all the above, he realised.

That night they made love, hesitantly, and later lay in a parallelogram of moonlight that cut across the bed.

“What happened, Ed?” she asked.

“Mmm?” He tried to feign semi-wakefulness.

“We were there, in mission control. You were out with Spirek. Something happened. There was a loud . . . I don’t know, it sounded like a landslide. You said, ‘Oh my God . . .’. Roberts cut the link and ushered us out. It was an hour before they got back to us. An hour. Can you imagine that? I was worried sick.”

He reached out and stroked away her tears.

“Roberts gave us some story about subsidence,” she said. “Then I heard you again, reassuring us that everything was okay.”

They had staged that, concocted a few lines between them, directed by Roberts, to reassure their families back home.

He shrugged. “That’s it. That’s what happened. I was caught in a landslide, lost my footing.” Even to his own ears, he sounded unconvincing.

Delia went on, “And then three days ago, I could tell something wasn’t right. And now . . . You’re hiding something.”

He let the silence stretch. “I’m hiding nothing. It’s hard to readjust. Imagine being stuck in a tin can for three years with cretins like Jeffries and McCarthy.”

“You’re too sensitive, Ed. You’re a geologist, not an astronaut. You should have stayed at the university.”

He embraced her. “Shh,” he said, and fell silent.

He dreamed that night. He was back on Mars. He could feel the regolith slide away beneath his boots. The sensation of inevitable descent and imminent impact turned his stomach as it had done all those months ago. He fell, tumbling, and landed in a sitting position. In the dream he opened his eyes – and awoke suddenly.

He gasped aloud and reached out, grabbed the headboard. Then it came to him that he was no longer weightless, floating in his sleeping bag. He was on Earth. He was home. He reached out for Delia and held her.

In the morning, while Delia was at school, Enright took a walk. The open space, after so long cramped in the Fortitude, held an irresistible allure. He found himself on the golf course, strolling along the margin of the second fairway in the shade of maple trees.

He came to a bunker and stopped, staring at the clean, scooped perfection of the feature. He closed his eyes, and jumped. The sensation was pretty accurate. He had stepped out onto Mars again. He felt the granular regolith give beneath his boots.

When he opened his eyes he saw a young girl, perhaps twelve years old and painfully pretty. She was standing on the lip of the bunker, staring down at him.

She was clutching a pen and a scrap of paper.

Beyond her, on the green, two men looked on.

“Mr Enright, sir?” the kid asked. “Can I have your autograph?”

He reached up, took the pen and paper, and scrawled his name.

The girl stared at the autograph, as if the addition of his signature upon the paper had invested it with magical properties. One of the watching men smiled and waved a hand.

Delia was still at school when he got back. The first thing he did on returning was to phone a scrap merchant to take away the swing in the back yard. Then he retired to his study and stared at the pile of unanswered correspondence on his desk.

He leafed through the mail.

One was from Joshua Connaught, in England. Enright had corresponded with the eccentric for a number of years before the mission. The man had said he was writing a book on the history of spaceflight, and wanted Enright’s opinion on certain matters.

They had exchanged letters every couple of months, moving away from the original subject and discussing everything under the sun. Connaught had been married, once, and he too was childless.

Enright set the envelope aside, unopened.

He sat back in his armchair and closed his eyes.

He was back on Mars again, falling . . .

It had been a perfect touchdown.

The first manned craft to land on another planet had done so at precisely 3.33 a.m., Houston time, 2 September, 2020.

Enright recalled little of the actual landing, other than his fear. He had never been a good flyer – plane journeys had given him the shakes: he feared the take-off and landings, while the bit in between he could tolerate. The same was true of spaceflight. The take-off at Kennedy had been delayed by a day, and then put on hold for another five hours, and by the time the Fortitude did blast off from pad 39A, Enright had been reduced to a nervous wreck. Fortunately, his presence at this stage of the journey had been token. It was the others who did the work – just as when they came in to land, over eighteen months later, on the broad, rouge expanse of the Amazonis Planitia.

Enright recalled gripping the arms of his seat to halt the shakes that had taken him, and staring through the view-screen at the rocky surface of Mars which was rushing up to meet them faster than seemed safe.

Jeffries had seen him and laughed, nudging McCarthy to take a look. Fortunately, the air force man had been otherwise occupied. Only Spirek sympathized with a smile; Enright received the impression that she too was not enjoying the descent.

The retros cut in, slamming the seat into Enright’s back and knocked the wind from him. The descent of the lander slowed appreciably. The boulder strewn terrain seemed to be floating up to meet them, now.

Touchdown, when it came, was almost delicate.

McCarthy and Jeffries were NASA men through and through, veterans of a dozen space station missions and the famous return to the moon in ’15. They were good astronauts, lousy travelling companions. They were career astronauts who were less interested in the pursuit of knowledge, of exploration for its own sake, than in the political end-results of what they were doing – both for themselves personally, and for the country. Enright envisaged McCarthy running for president in the not too distant future, Jeffries ending up as some big-wig in the Pentagon.

They tended to look upon Enright, with his PhD in geology and a career at Miami university, as something of a make-weight on the trip.

Spirek . . . Enright could not quite make her out. Like the others, she was a career astronaut, but she had none of the brash bravado and right-wing rhetoric of her male counterparts. She had been a pilot in the air force, and was along as team medic and multi-disciplinary scientist: her brief, to assess the planet for possible future colonization.

McCarthy was slated to step out first, followed by Enright. Fancy that, he’d thought on being informed at the briefing, Iowa farm-boy made good, only the second human being ever to set foot on Mars . . .

After the landing, Jeffries had made some quip about Enright still being shit scared and not up to taking a stroll. He’d even made to suit up ahead of Enright.

“I’m fine,” Enright said.

Spirek had backed him up. “Ed’s AOK for go, Jeffries. You don’t want Roberts finding out you pulled a stunt, huh?”

Jeffries had muttered something under his breath. It had sounded like “Bitch,” to Enright.

So he’d followed McCarthy out onto the sun-bright plain of the Amazonis Planitia, his pulse loud in his ears, his legs trembling as he climbed the ladder and stepped onto the surface of the alien world.

There was a lot to do for the two hours he was out of the lander, and he had only the occasional opportunity to consider the enormity of the situation.

He took rock samples, drilled through the regolith to the bedrock. He filmed what he was doing for the benefit of the geologists back at NASA who would take up the work when he returned.

He recalled straightening up on one occasion and staring, amazed, at the western horizon. He wondered how he had failed to notice it before. The mountain stood behind the lander, an immense pyramidal shape that rose abruptly from the surrounding volcanic plain to a height, he judged, of a kilometre. He had to tilt his head back to take in its summit.

Later, Spirek and Jeffries took their turn outside, while Enright began a preliminary analysis of the rock samples and McCarthy reported back to mission control.

Day one went like a dream, everything AOK.

The following day, as the sun rose through the cerise sky, Enright and Spirek took the Mars-mobile out for its test drive. They ranged a kilometre from the lander, keeping it in sight at all times.

Spirek, driving, halted the vehicle at one point and stared into the sky. She touched Enright’s padded elbow, and he heard her voice in his ear-piece. “Look, Ed.” And she pointed.

He followed her finger, and saw a tiny, shimmering star high in the heavens.

“Earth,” she whispered, and, despite himself, Enright felt some strange emotion constrict his throat at the sight of the planet, so reduced.

But for Spirek’s sighting of Earth at that moment, and her decision to halt, Enright might never have made the discovery that was to prove so fateful.

Spirek was about to start up, when he glanced to his left and saw the depression in the regolith, ten metres from the Mars-mobile.

“Hey! Stop, Sally!”

“What is it?”

He pointed. “Don’t know. Looks like subsidence. I want to take a look.”

Sal glanced at her chronometer. “You got ten minutes, okay?”

He climbed from the mobile and strode towards the rectangular impression in the red dust. He paused at its edge, knelt and ran his hand through the fine regolith. The first human being, he told himself, ever to do so here at this precise location . . .

He stood and took a step forward.

And the ground gave way beneath his feet, and he was falling. “Oh, my God!”

He landed in a sitting position in semi-darkness, battered and dazed but uninjured. He checked his life-support apparatus. His suit was okay, his air supply functioning.

Only then did he look around him. He was in a vast chamber, a cavern that extended for as far as the eye could see.

As the dust settled, he made out the objects ranged along the length of the chamber.

“Oh, Christ,” he cried. “Spirek . . . Spirek!”

He stood in the doorway of the conservatory and watched the workmen dismantle the swing and load it onto the back of the pick-up.

He’d been home four days now, and he was falling back into the routine of things. Breakfast with Delia, then a round of golf, solo, on the mornings she worked. They met for lunch in town, and then spent the afternoons at home, Delia in the garden, Enright reading magazines and journals in the conservatory.

He was due to start back at the university in a week, begin work on the samples he’d brought back from Mars. He was not relishing the prospect, and not just because it would mean spending time away from Delia: the business of geology, and what might be learned from the study of the Martian rocks, palled beside what he’d discovered on the red planet.

Roberts had phoned him a couple of days ago. Already NASA was putting together plans for a follow-up mission. He recalled what McCarthy and Jeffries had said about their discovery, that it constituted a security risk. Enright had forced himself not to laugh out loud, at the time. And yet, amazingly, when he returned to Earth and heard the talk of the back-room boys up at Kennedy, that had been the tenor of their concern. Now Roberts confirmed it by telling him, off the record, that the government was bankrolling the next Mars mission. There would be a big military presence aboard. He wondered if McCarthy and Jeffries were happy now.

The workmen finished loading the frame of the swing and drove off. Delia was kneeling in the border, weeding. He watched her for a while, then went into the house.

He fetched the papers from the sitting room where he’d discovered them yesterday, slipped under the cushion of the settee.

“Delia?”

She turned, smiling.

She saw the papers and her smile faltered. Her eyes became hard. “I was just looking them over. I wasn’t thinking of . . .”

“We talked about this, Delia.”

“What, five years ago, more? Things are different now. You’re back at university. I can quit work. Ed,” she said, something like a plea in her tone, “we’d be perfect. They’re looking for people like us.”

He sat down on the grass, laid the brochure down between himself and his wife. The wind caught the cover, riffled pages. He saw a gallery of beseeching faces staring out at him, soft focus shots manufactured to pluck at the heart-strings of childless couples like themselves.

He reached out and stopped the pages. He stared at the picture of a small blonde-haired girl. She reminded him of the kid who’d asked for his signature at the golf course the other day.

And, despite himself, he felt a longing somewhere deep within him like an ache.

“Why are you so against the idea, Ed?”

They had planned to start a family in the early years. Then Delia discovered that she was unable to bear children. He had grown used to the idea that their marriage would be childless, though it was harder for Delia to accept. Over the years he had devoted himself to his wife, and when five years ago she had first mentioned the possibility of adoption, he had told her he loved her so much that he would be unable to share that love with a child. He was bullshitting, of course. The fact was that he did not want Delia’s love for him diluted by another.

And now? Now, he felt the occasional craving to lavish love and affection on a child, and he could not explain his uneasiness at the prospect of acceding to his wife’s desires.

He shook his head, wordlessly, and a long minute later he stood and returned to the house.

The following day Delia sought him out in his study. He’d retreated there shortly after breakfast, and for the past hour had been staring at his replica sixteenth-century globe of the world. He considered crude, formless shapes that over the years had been redefined as countries and continents.

Terra incognita . . .

A sound interrupted his reverie. Delia paused by the door, one hand touching the jamb. She was carrying a newspaper.

She entered the room and sat down on the very edge of the armchair beside the bookcase. He managed a smile.

“You haven’t been yourself since you got back.”

“I’m sorry. It must be the strain. I’m tired.”

She nodded, let the silence develop. “Did you know, there were stories at the time? The Net was buzzing with rumours, speculation.”

He smiled at that. “I should hope so. Humankind’s first landing on Mars . . .”

“Besides that, Ed. When you fell, and the broadcast was suddenly cut.”

“What we’re they saying? That we’d been captured by little green men?”

“Not in so many words. But they were speculating . . . said you might have stumbled across some sign of life up there.” She stopped, then said, “Well?”

“Well, what?”

“What happened?”

He sighed. “So you’d rather believe some crazy press report –?”

She stopped him by holding out the morning paper. The headline of the Miami Tribune ran: LIFE ON MARS?

He took the paper and read the report.

Speculation was growing today surrounding man’s first landing on the red planet. Leaks from NASA suggest that astronauts McCarthy, Jeffries, Enright and Spirek discovered ancient ruins on their second exploratory tour of the red planet. Unconfirmed reports suggest that . . .

Enright stopped reading and passed the paper back to his wife.

“Unconfirmed reports, rumours. Typical press speculation.”

“So nothing happened?”

“What do you want me to say? I fell down a hole – but I didn’t find Wonderland down there.”

Later, when she left without another word, he chastised himself for such a cheap parting shot.

He hadn’t found Wonderland down there, but something far stranger instead.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...