- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

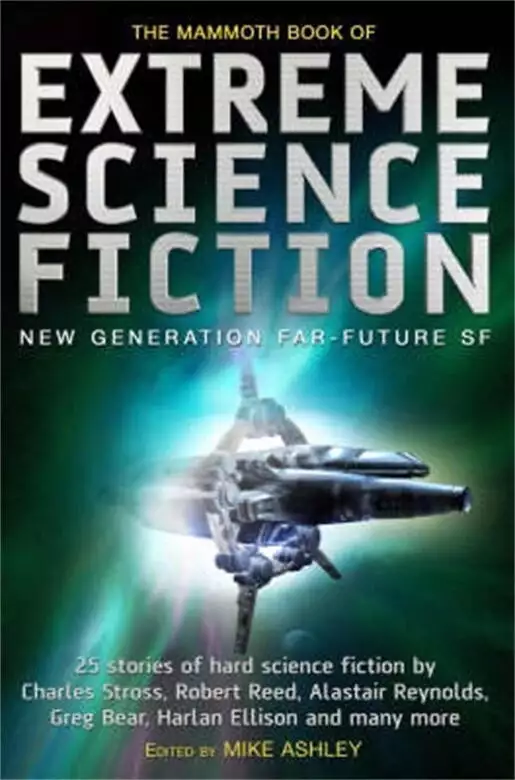

Here are 25 stories of science fiction that push the envelope, by the biggest names in an emerging new crop of high-tech futuristic SF - including Charles Stross, Robert Reed, Alastair Reynolds, Peter Hamilton and Neal Asher. High-tech SF has made a significant comeback in the last decade, as bestselling authors successfully blend the super-science of ''hard science fiction'' with real characters in an understandable scenario. It is perhaps a reflection of how technologically controlled our world is that readers increasingly look for science fiction that considers the fates of mankind as a result of increasing scientific domination. This anthology brings together the most extreme examples of the new high-tech, far-future science fiction, pushing the limits way beyond normal boundaries. The stories include: "A Perpetual War Fought Within a Cosmic String", "A Weapon That Could Destroy the Universe", "A Machine That Detects Alternate Worlds and Creates a Choice of Christs", "An Immortal Dead Man Sent To The End of the Universe", "Murder in Virtual Reality", "A Spaceship So Large That There is An Entire Planetary System Within It", and "An Analytical Engine At The End of Time", and "Encountering the Untouchable."

Release date: July 31, 2010

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Extreme Science Fiction

Mike Ashley

The Mammoth Book of 20th Century Science Fiction

The Mammoth Book of Best New Erotica 4

The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror 16

The Mammoth Book of Best New Science Fiction 18

The Mammoth Book of Celebrity Murder

The Mammoth Book of Celtic Myths and Legends

The Mammoth Book of Chess

The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Comic Quotes

The Mammoth Book of Dirty, Sick X-Rated & Politically Incorrect Jokes

The Mammoth Book of Egyptian Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Erotic Online Diaries

The Mammoth Book of Erotic Photography

The Mammoth Book of Erotic Women

The Mammoth Book of Great Detective Stories

The Mammoth Book of Great Inventions

The Mammoth Book of Haunted House Stories

The Mammoth Book of Historical Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Illustrated True Crime

The Mammoth Book of IQ Puzzles

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: Ancient Egypt

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: Ancient Rome

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: Battles

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: Trafalgar

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: WWI

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: WW II

The Mammoth Book of Jokes

The Mammoth Book of King Arthur

The Mammoth Book of Lesbian Erotica

The Mammoth Book of Maneaters

The Mammoth Book of Mountain Disasters

The Mammoth Book of New Terror

The Mammoth Book of New Jules Verne Adventures

The Mammoth Book of On the Road

The Mammoth Book of Private Eye Stories

The Mammoth Book of Roaring Twenties Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Roman Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Seriously Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Sex, Drugs & Rock ‘n’ Roll

The Mammoth Book of Short Spy Novels

The Mammoth Book of Sorcerers’ Tales

The Mammoth Book of Space Exploration and Disasters

The Mammoth Book of SAS & Special Forces

The Mammoth Book of Shipwrecks & Sea Disasters

The Mammoth Book of Short Erotic Novels

The Mammoth Book of On The Edge

The Mammoth Book of Travel in Dangerous Places

The Mammoth Book of True Crime

The Mammoth Book of True War Stories

The Mammoth Book of Unsolved Crimes

The Mammoth Book of Vampires

The Mammoth Book of Wild Journeys

The Mammoth Book of Women’s Fantasies

The Mammoth Book of Women Who Kill

The Mammoth Book of the World’s Greatest Chess Games

The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Unsolved Mysteries

I would like to thank those who came up with their own suggestions of extreme sf stories including Gordon Van Gelder, Rich Horton, Todd Mason, David Pringle, Andy Robertson and in particular Jetse de Vries, whose taste coincides remarkably with my own. All of the stories are copyright in the name of the individual authors or their estates as follows. Every effort has been made to trace holders of copyright. In the event of any inadvertent transgression please contact the editor via the publisher.

“The Pacific Mystery” © 2006 by Stephen Baxter. First publication, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“Judgment Engine” © 1995 by Greg Bear. First published in Far Futures edited by Gregory Benford (New York: Tor Books, 1995). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Anomalies” by Gregory Benford © 1999 by Abbenford Associaties. First published in Redshift edited by Al Sarrantonio (New York: Roc Books, 2001). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Death in the Promised Land” © 1995 by Pat Cadigan. First published by OMNI Online in March 1995 and first printed in Asimov’s Science Fiction, November 1995. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“. . . And the Dish Ran Away with the Spoon” © 2003 by Paul Di Filippo. First published by SCI FICTION, 19 November 2003. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Flowers from Alice” © 2003 by Cory Doctorow and Charles Stross. First published in New Voices in Science Fiction edited by Mike Resnick (New York: DAW Books, 2003). Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“Wang’s Carpets” © 1995 by Greg Egan. First published in New Legends edited by Greg Bear (London and New York: Legend Books, 1995). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Region Between” © 1969 by harlan Ellison. Renewed 1997 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation. First published in Galaxy Science Fiction Magazine, March 1970. Reprinted by arrangement with and permission of the author and the author’s agent, Richard Curtis Associates, Inc., New York. All rights reserved. Harlan Ellison is a registered trademark of The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“Waterworld” © 1994 by Stephen Gillett & Jerry Oltion. First published in Analog Science Fiction and Fact, March 1994. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“Undone” © 2001 by James Patrick Kelly. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, June 2001. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Long Chase” © 2002 by Geoffrey A. Landis. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, February 2002. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Days of Solomon Gursky” © 1998 by Ian McDonald. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, June 1998. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Stuffing” © 2006 by Jerry Oltion. First publication, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“Crucifixion Varations” © 1998 by Lawrence Person. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, May 1998. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Hoop-of-Benzene” © 2006 by Robert Reed. First publication, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“Merlin’s Gun” © 2000 by Alastair Reynolds. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, May 2000. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Creator” © 1935 by Clifford D. Simak. First published in Marvel Tales, March-April 1935. Reprinted by permission of David Wixon on behalf of the author’s estate.

“The Girl Had Guts” © 1956 by Theodore Sturgeon. First published in Venture Science Fiction, January 1957. Reprinted by permission of The Theodore Sturgeon Literary Trust c/o Ralph M. Vicinanza, Ltd.

“The New Humans” © 1909 by B. Vallance. First published in Pearson’s Magazine, December 1909. Unable to trace the author or their estate.

If science fiction is the literature of ideas, then extreme science fiction is about extreme ideas. What you will find in this anthology are some wonderful ideas, which may in themselves be either simple or complicated, but which the author has taken to an extreme – be it extreme circumstances, an extreme location, extreme science or extreme concepts.

But there is a limit! These stories may push back boundaries and challenge existing beliefs and theories, but not at the sake of everything else. At their heart these are good, sound stories – there’s nothing experimental or avant garde about them – and you don’t need a science degree or an IQ over 200 to understand them. That’s not what it’s about. It’s about having fun with a thought, an idea, a vision. Science fiction is the best medium for doing this and the best science fiction is that which does push limits.

Let me give you some idea of what you’ll find here.

An Earth where the Pacific has never been crossed because somehow the Earth doesn’t quite join up.

crimes committed in virtual reality.

household machines that become sentient and take control.

a world made entirely of water.

someone lost in time trying to get back to where they started.

what happens if we all stop eating food.

That’s just a half-dozen of the ideas included in the nineteen stories in this collection. Not all are extreme in themselves, it’s what the author does with them.

Most of the stories are of a fairly recent vintage, written in the last ten or twelve years (three of them have their first appearance here). For the most part I wanted stories that were at the cutting edge of science and society. We have witnessed a colossal change in technological advance in the last twenty years or so and the pace of advance is increasing at a formidable rate. I wanted stories that recognized that pace of change and which incorporated much of the new technology and understanding.

But I didn’t want to exclude older science fiction. In fact one could argue than in its youth science fiction was at its most extreme. After all, imagine just how revolutionary Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was when it first appeared in 1818, or H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine in 1895. That took us firstly 800,000 years and then millions of years into the future. Or Edwin Abbott’s Flatland (1884) which explored a world of only two dimensions. That amazing philosopher Olaf Stapledon produced what must be one of the most extreme works of sf ever written with The Star Maker, published in 1937. This book has an observer witness the entire history of the Universe in which the part played by humanity is but a few pages. These works were certainly extreme for their day.

Some of these older stories have dated a little today, though they are still fun to read, and many are just too long to squeeze in, so I have been highly selective in what few stories I have reprinted from beyond the last thirty years. But I think you’ll be surprised.

Over the years there have been plenty of magazines and anthologies that have sought to break down barriers and taboos, most notably Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions, and there are a couple of examples of such stories included here. But this anthology isn’t designed as one that breaks taboos – such that remain. It’s designed to show what science fiction can do when it lets its hair down, which means that you are in for a roller coaster ride of awe and wonder.

I’ve arranged the book so that it starts with the least extreme and builds up to the most extreme, although the very last story allows us a mental cool down. So tread carefully. From here on the brakes are off.

Mike Ashley, December 2005

Gregory Benford

I could have filled this book entirely with stories by Greg Benford as he has written some of the best “extreme sf” of recent years. Just check out his collection Worlds Vast and Various (2000) for some of the latest examples. Benford (b. 1941) is a professor of physics at the University of California, Irvine, specializing in plasma turbulence and astrophysics. He advises NASA on national space policy and has been heavily involved in the Mars exploration programme. His novels, The Martian Race (1999) and The Sunborn (2005), are generally regarded as amongst the most authentic considerations of the race to and exploration of Mars. In 1995 he received the prestigious Lord Foundation award for scientific achievement.

In the world of science fiction, Benford has received many awards including the Nebula for Timescape (1980), still one of the most realistic time-travel novels. His most sustained sequence of books is the Galactic Centre series, tracing the continuing conflict between organic life forms and AI machines. The series began with Across the Sea of Suns (1983). Amongst his more recent novels perhaps the most extreme is Cosm (1998) involving an artificially created micro-universe. You might also want to check out the anthology he edited, Far Futures (1995), which is full of extreme sf, including Greg Bear’s story, which you’ll find later in this volume.

To get us underway, here is Benford in milder, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, mood.

It was not lost upon the Astronomer Royal that the greatest scientific discovery of all time was made by a carpenter and amateur astronomer from the neighbouring cathedral town of Ely. Not by a Cambridge man.

Geoffrey Carlisle had a plain directness that apparently came from his profession, a custom cabinet-maker. It had enabled him to get past the practised deflection skills of the receptionist at the Institute for Astronomy, through the Assistant Director’s patented brush-off, and into the Astronomer Royal’s corner office.

Running this gauntlet took until early afternoon, as the sun broke through a shroud of soft rain. Geoffrey wasted no time. He dropped a celestial coordinate map on the Astronomer Royal’s mahogany desk, hand amended, and said, “The moon’s off by better’n a degree.”

“You measured carefully, I am sure.”

The Astronomer Royal had found that the occasional crank did make it through the Institute’s screen, and in confronting them it was best to go straight to the data. Treat them like fellow members of the profession and they softened. Indeed, astronomy was the only remaining science that profited from the work of amateurs. They discovered the new comets, found wandering asteroids, noticed new novae and generally patrolled what the professionals referred to as local astronomy – anything that could be seen in the night sky with a telescope smaller than a building.

That Geoffrey had got past the scrutiny of the others meant this might conceivably be real. “Very well, let us have a look.” The Astronomer Royal had lunched at his desk and so could not use a date in his college as a dodge. Besides, this was crazy enough perhaps to generate an amusing story.

An hour later he had abandoned the story-generating idea. A conference with the librarian, who knew the heavens like his own palm, made it clear that Geoffrey had done all the basic work correctly. He had photos and careful, carpenter-sure data, all showing that, indeed, last night after around eleven o’clock the moon was well ahead of its orbital position.

“No possibility of systematic error here?” the librarian politely asked the tall, sinewy Geoffrey.

“Check ’em yerself. I was kinda hopin ’you fellows would have an explanation, is all.”

The moon was not up, so the Astronomer Royal sent a quick email to Hawaii. They thought he was joking, but then took a quick look and came back, rattled. A team there got right on it and confirmed. Once alerted, other observatories in Japan and Australia chimed in.

“It’s out of position by several of its own diameters,” the Astronomer Royal mused. “Ahead of its orbit, exactly on track.”

The librarian commented precisely, “The tides are off prediction as well, exactly as required by this new position. They shifted suddenly, reports say.”

“I don’t see how this can happen,” Geoffrey said quietly.

“Nor I,” the Astronomer Royal said. He was known for his understatement, which could masquerade as modesty, but here he could think of no way to underplay such a result.

“Somebody else’s bound to notice, I’d say,” Geoffrey said, folding his cap in his hands.

“Indeed.” The Astronomer Royal suspected some subtlety had slipped by him.

“Point is, sir, I want to be sure I get the credit for the discovery.”

“Oh, of course you shall.” All amateurs ever got for their labors was their name attached to a comet or asteroid, but this was quite different. “Best we get on to the IAU, ah, the International Astronomical Union,” the Astronomer Royal said, his mind whirling. “There’s a procedure for alerting all interested observers. Establish credit, as well.”

Geoffrey waved this away. “Me, I’m just a five-inch ’scope man. Don’t care about much beyond the priority, sir. I mean, it’s over to you fellows. What I want to know is, what’s it mean?”

Soon enough, as the evening news blared and the moon lifted above the European horizons again, that plaintive question sounded all about. One did not have to be a specialist to see that something major was afoot.

“It all checks,” the Astronomer Royal said before a forest of cameras and microphones. “The tides being off true has been noted by the naval authorities round the world, as well. Somehow, in the early hours of last evening, Greenwich time, our moon accelerated in its orbit. Now it is proceeding at its normal speed, however.”

“Any danger to us?” one of the incisive, investigative types asked.

“None I can see,” the Astronomer Royal deflected this mildly. “No panic headlines needed.”

“What caused it?” a woman’s voice called from the media thicket.

“We can see no object nearby, no apparent agency,” the Astronomer Royal admitted.

“Using what?”

“We are scanning the region in all wavelengths, from radio to gamma rays.” An extravagant waste, very probably, but the Astronomer Royal knew the price of not appearing properly concerned. Hand-wringing was called for at all stages.

“Has this happened before?” a voice sharply asked. “Maybe we just weren’t told?”

“There are no records of any such event,” the Astronomer Royal said. “Of course, a thousand years ago, who would have noticed? The supernova that left us the Crab nebula went unreported in Europe, though not in China, though it was plainly visible here.”

“What do you think, Mr Carlisle?” a reporter probed. “As a non-specialist?”

Geoffrey had hung back at the press conference, which the crowds had forced the Institute to hold on the lush green lawn outside the old Observatory Building. “I was just the first to notice it,” he said. “That far off, pretty damned hard not to.”

The media mavens liked this and coaxed him further. “Well, I dunno about any new force needed to explain it. Seems to me, might as well say it’s supernatural, when you don’t know anything.”

This the crowd loved. SUPER AMATEUR SAYS MOON IS SUPERNATURAL soon appeared on a tabloid. They made a hero of Geoffrey. “AS OBVIOUS AS YOUR FACE” SAYS GEOFF. The London Times ran a full-page reproduction of his log book, from which he and the Astronomer Royal had worked out that the acceleration had to have happened in a narrow window around ten p.m., since no observer to the east had noticed any oddity before that.

Most of Europe had been clouded over that night anyway, so Geoffrey was among the first who could have had a clear view after what the newspapers promptly termed The Anomaly, as in ANOMALY MAN STUNS ASTROS.

Of the several thousand working astronomers in the world, few concerned themselves with “local” events, especially not with anything the eye could make out. But now hundreds threw themselves upon The Anomaly and, coordinated at Cambridge by the Astronomer Royal, swiftly outlined its aspects. So came the second discovery.

In a circle around where the moon had been, about two degrees wide, the stars were wrong. Their positions had jiggled randomly, as though irregularly refracted by some vast, unseen lens.

Modern astronomy is a hot competition between the quick and the dead – who soon become the untenured.

Five of the particularly quick discovered this Second Anomaly. They had only to search all ongoing observing campaigns and find any that chanced to be looking at that portion of the sky the night before. The media, now in full bay, headlined their comparison photos. Utterly obscure dots of light became famous when blink-comparisons showed them jumping a finger’s width in the night sky, within an hour of the 10 p.m. Anomaly Moment.

“Does this check with your observations?” a firm-jawed commentator had demanded of Geoffrey at a hastily called meeting one day later, in the auditorium at the Institute for Astronomy. They called upon him first, always – he served as an anchor amid the swift currents of astronomical detail.

Hooting from the traffic jam on Madingley Road nearby nearly drowned out Geoffrey’s plaintive, “I dunno. I’m a planetary man, myself.”

By this time even the nightly news broadcasts had caught onto the fact that having a patch of sky behave badly implied something of a wrenching mystery. And no astronomer, however bold, stepped forward with an explanation. An old joke with not a little truth in it – that a theorist could explain the outcome of any experiment, as long as he knew it in advance – rang true, and got repeated. The chattering class ran rife with speculation.

But there was still nothing unusual visible there. Days of intense observation in all frequencies yielded nothing.

Meanwhile the moon glided on in its ethereal ellipse, following precisely the equations first written down by Newton, only a mile from where the Astronomer Royal now sat, vexed, with Geoffey. “A don at Jesus College called, fellow I know,” the Astronomer Royal said. “He wants to see us both.”

Geoffrey frowned. “Me? I’ve been out of my depth from the start.”

“He seems to have an idea, however. A testable one, he says.”

They had to take special measures to escape the media hounds. The Institute enjoys broad lawns and ample shrubbery, now being trampled by the crowds. Taking a car would guarantee being followed. The Astronomer Royal had chosen his offices here, rather than in his college, out of a desire to escape the busyness of the central town. Now he found himself trapped. Geoffrey had the solution. The Institute kept bicycles for visitors, and upon two of these the men took a narrow, tree-lined path out the back of the Institute, toward town. Slipping down the cobbled streets between ancient, elegant college buildings, they went ignored by students and shoppers alike. Jesus College was a famously well appointed college along the Cam river, approachable across its ample playing fields. The Astronomer Royal felt rather absurd to be pedaling like an undergraduate, but the exercise helped clear his head. When they arrived at the rooms of Professor Wright, holder of the Wittgenstein Chair, he was grateful for tea and small sandwiches with the crusts cut off, one of his favourites.

Wright was a post-postmodern philosopher, reedy and intense. He explained in a compact, energetic way that in some sense, the modern view was that reality could be profitably regarded as a computation.

Geoffrey bridled at this straight away, scowling with his heavy eyebrows. “It’s real, not a bunch of arithmetic.”

Wright pointedly ignored him, turning to the Astronomer Royal. “Martin, surely you would agree with the view that when you fellows search for a Theory of Everything, you are pursuing a belief that there is an abbreviated way to express the logic of the universe, one that can be written down by human beings?”

“Of course,” the Astronomer Royal admitted uncomfortably, but then said out of loyalty to Geoffrey, “All the same, I do not subscribe to the belief that reality can profitably be seen as some kind of cellular automata, carrying out a program.”

Wright smiled without mirth. “One might say you are revolted not by the notion that the universe is a computer, but by the evident fact that someone else is using it.”

“You gents have got way beyond me,” Geoffrey said.

“The idea is, how do physical laws act themselves out?” Wright asked in his lecturer voice. “Of course, atoms do not know their own differential equations.” A polite chuckle. “But to find where the moon should be in the next instant, in some fashion the universe must calculate where it must go. We can do that, thanks to Newton.”

The Astronomer Royal saw that Wright was humoring Geoffrey with this simplification, and suspected that it would not go down well. To hurry Wright along he said, “To make it happen, to move the moon—”

“Right, that we do not know. Not a clue. How to breathe fire into the equations, as that Hawking fellow put it—”

“But look, nature doesn’t know maths,” Geoffrey said adamantly. “No more than I do.”

“But something must, you see,” Professor Wright said earnestly, offering them another plate of the little cut sandwiches and deftly opening a bottle of sherry. “Of course I am using our human way of formulating this, the problem of natural order. The world is usefully described by mathematics, so in our sense the world must have some mathematics embedded in it.”

“God’s a bloody mathematician?” Geoffrey scowled.

The Astronomer Royal leaned forward over the antique oak table. “Merely an expression.”

“Only way the stars could get out of whack,” Geoffrey said, glancing back and forth between the experts, “is if whatever caused it came from there, I’d say.”

“Quite right.” The Astronomer Royal pursed his lips. “Unless the speed of light has gone off, as well, no signal could have rearranged the stars straight after doing the moon.”

“So we’re at the tail end of something from out there, far away,” Geoffrey observed.

“A long, thin disturbance propagating from distant stars. A very tight beam of . . . well, error. But from what?” The Astronomer Royal had had little sleep since Geoffrey’s appearance, and showed it.

“The circle of distorted stars,” Professor Wright said slowly, “remains where it was, correct?”

The Astronomer Royal nodded. “We’ve not announced it, but anyone with a cheap telescope – sorry, Geoffrey, not you, of course – can see the moon’s left the disturbance behind, as it follows its orbit.”

Wright said, “Confirming Geoffrey’s notion that the disturbance is a long, thin line of – well, I should call it an error.”

“Is that what you meant by a checkable idea?” the Astronomer Royal asked irritably.

“Not quite. Though that the two regions of error are now separating, as the moon advances, is consistent with a disturbance traveling from the stars to us. That is a first requirement, in my view.”

“Your view of what?” Geoffrey finally gave up handling his small sherry glass and set it down with a decisive rattle.

“Let me put my philosophy clearly,” Wright said. “If the universe is an ongoing calculation, then computational theory proves that it cannot be perfect. No such system can be free of a bug or two, as the programmers put it.”

Into an uncomfortable silence Geoffrey finally inserted, “Then the moon’s being ahead, the stars – it’s all a mistake?”

Wright smiled tightly. “Precisely. One of immense scale, moving at the speed of light.”

Geoffrey’s face scrunched into a mask of perplexity. “And it just – jumped?”

“Our moon hopped forward a bit too far in the universal computation, just as a program advances in little leaps.” Wright smiled as though this were an entirely natural idea.

Another silence. The Astronomer Royal said sourly, “That’s mere philosophy, not physics.”

“Ah!” Wright pounced. “But any universe which is a sort of analog computer must, like any decent digital one, have an errorchecking program. Makes no sense otherwise.”

“Why?” Geoffrey was visibly confused, a craftsman out of his depth.

“Any good program, whether it is doing accounts in a bank, or carrying forward the laws of the universe, must be able to correct itself.” Professor Wright sat back triumphantly and swallowed a Jesus College sandwich, smacking his lips.

The Astronomer Royal said, “So you predict . . .?”

“That both the moon and the stars shall snap back, get themselves right – and at the same time, as the correction arrives here at the speed of light.”

“Nonsense,” the Astronomer Royal said.

“A prediction,” Professor Wright said sternly. “My philosophy stands upon it.”

The Astronomer Royal snorted, letting his fatigue get to him. Geoffrey looked puzzled, and asked a question which would later haunt them.

Professor Wright did not have long to wait.

To his credit, he did not enter the media fray with his prediction. However, he did unwisely air his views at High Table, after a particularly fine bottle of claret brought forward by the oldest member of the college. Only a generation or two earlier, such a conversation among the Fellows would have been secure. Not so now. A Junior Fellow in Political Studies proved to be on a retainer from The Times, and scarcely a day passed before Wright’s conjecture was known in New Delhi and Tokyo.

The furor following from that had barely subsided when the Astronomer Royal received a telephone call from the Max Planck Institute. They excitedly reported that the moon, now under continuous observation, had shifted instantly to the position it should have, had its orbit never been perturbed.

So, too, did the stars in the warped circle return to their rightful places. Once more, all was right with the world. Even so, it was a world that could never again be the same.

Professor Wright was not smug. He received the news from the Astronomer Royal, who had brought along Geoffrey to Jesus College, a refuge now from the Institute. “Nothing, really, but common sense.” He waved away their congratulations.

Geoffrey sat, visibly uneasily, through some talk about how to handle all this in the voracious media glare. Philosophers are not accustomed to much attention until well after they are dead. But as discussion ebbed Geoffrey repeated his probing question of days before: “What sort of universe has mistakes in it?”

Professor Wright said kindly, “An information-ordered one. Think of everything that happens – including us talking here, I suppose – as a kind of analog program acting out. Discovering itself in its own development. Manifesting.”

Geoffrey persisted, “But who’s the programmer of this computer?”

“Questions of first cause are really not germane,” Wright said, drawing himself up.

“Which means that he cannot say,” the Astronomer Royal allowed himself.

Wright stroked his chin at this and eyed the others before venturing, “In light of the name of this college, and you, Geoffrey, being a humble bearer of the message that began all this . . .”

“Oh no,” the Astronomer Royal said fiercely, “next you’ll point out that Geoffrey’s a carpenter.”

They all laughed, though uneasily.

But as the Astronomer Royal and Geoffrey left the venerable grounds, Geoffrey said moodily, “Y’know, I?

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...