- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

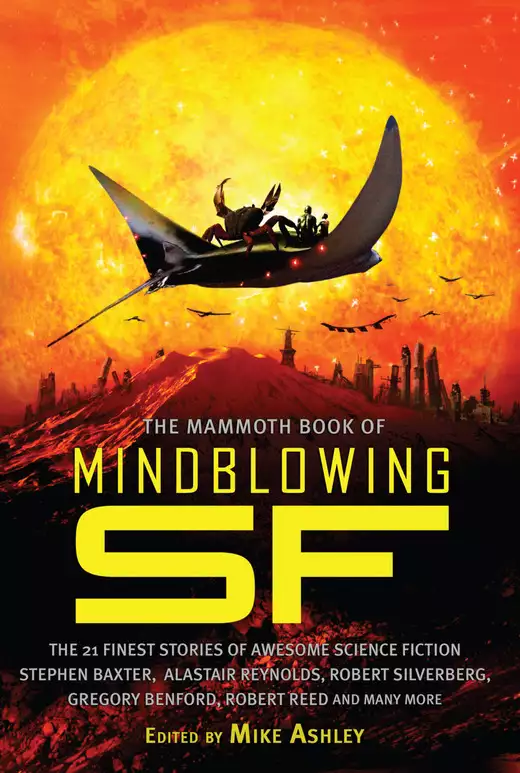

Many readers are attracted to science fiction for that singular moment when a story expands your imagination, enabling you to see something in a new light. Not all SF works this way! This volume collects the very best of it that does, with 25 of the finest examples of mind-expanding and awe-inspiring science fiction. The storylines range from a discovery on the Moon that opens up vistas across all time to a moment in which distances across the Earth suddenly increase and people vanish. These are tales to take you from the other side of now to the very end of time - from today's top-name contributors including Stephen Baxter, Alastair Reynolds, Robert Silverberg, Gregory Benford and Robert Reed.

Release date: July 30, 2009

Publisher: Robinson

Print pages: 554

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Mindblowing SF

Mike Ashley

The Mammoth Book of Extreme Science Fiction, The Mammoth Book of Extreme Fantasy and The Mammoth Book of Perfect Crimes and Impossible Mysteries. He has also written the biography of

Algernon Blackwood, Starlight Man, and a comprehensive study The Mammoth Book of King Arthur. He lives in Kent with his wife and three cats and when he gets the time he likes to go

for long walks.

Also available

The Mammoth Book of 20th Century Science Fiction, vol. 2

The Mammoth Book of Best British Mysteries

The Mammoth Book of Best Horror Comics

The Mammoth Book of Best of the Best New SF

The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror 19

The Mammoth Book of Best New Manga 3

The Mammoth Book of Best New SF 21

The Mammoth Book of Best War Comics

The Mammoth Book of Book of Bikers

The Mammoth Book of Boys’ Own Stuff

The Mammoth Book of Brain Teasers The Mammoth Book of Brain Workouts The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy The Mammoth Book of Comic Quotes

The Mammoth Book of Cover-Ups

The Mammoth Book of Crime Comics

The Mammoth Book of The Deep

The Mammoth Book of Dickensian Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Egyptian Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Fast Puzzles

The Mammoth Book of Funniest Cartoons of All Time

The Mammoth Book of Great Inventions

The Mammoth Book of Hard Men

The Mammoth Book of Historical Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened: In Britain

The Mammoth Book of Illustrated True Crime

The Mammoth Book of Inside the Elite Forces

The Mammoth Book of Jacobean Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of King Arthur

The Mammoth Book of Limericks

The Mammoth Book of Martial Arts

The Mammoth Book of Men O’War

The Mammoth Book of Modern Battles

The Mammoth Book of Modern Ghost Stories

The Mammoth Book of Monsters

The Mammoth Book of Mountain Disasters

The Mammoth Book of New Sherlock Holmes

The Mammoth Book of New Terror

The Mammoth Book of On the Edge

The Mammoth Book of On the Road

The Mammoth Book of Pirates

The Mammoth Book of Poker

The Mammoth Book of Prophecies

The Mammoth Book of Short Spy Novels

The Mammoth Book of Sorcerers’ Tales

The Mammoth Book of Tattoos

The Mammoth Book of The Beatles

The Mammoth Book of The Mafia

The Mammoth Book of True Hauntings

The Mammoth Book of True War Stories

The Mammoth Book of Twenties Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Unsolved Crimes

The Mammoth Book of Vintage Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Wild Journeys

The Mammoth Book of Zombie Comics

Constable & Robinson Ltd

3 The Lanchesters

162 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 9ER

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson, 2009

Copyright © Mike Ashley, 2009 (unless otherwise indicated)

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in

any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication

Data is available from the British Library

UK ISBN 978-1-84529-891-3

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

First published in the United States in 2009 by

Running Press Book Publishers

All rights reserved under the Pan-American and

International Copyright Conventions

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information

storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the publisher.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Digit on the right indicates the number of this printing

US Library of Congress number: 2008944131

US ISBN 978-0-76243-723-8

Running Press Book Publishers

2300 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19103-4371

Visit us on the web!

www.runningpress.com

Printed and bound in the EU

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Out of the Sun, Arthur C. Clarke

The Pevatron Rats, Stephen Baxter

The Edge of the Map, Ian Creasey

Cascade Point, Timothy Zahn

A Dance to Strange Musics, Gregory Benford

Palindromic, Peter Crowther

Castle in the Sky, Robert Reed

The Hole in the Hole, Terry Bisson

Hotrider, Keith Brooke

Mother Grasshopper, Michael Swanwick

Waves and Smart Magma, Paul Di Filippo

The Black Hole Passes, John Varley

The Peacock King, Ted White & Larry McCombs

Bridge, James Blish

Anhedonia, Adam Roberts

Tiger Burning, Alastair Reynolds

The Width of the World, Ian Watson

Our Lady of the Sauropods, Robert Silverberg

Into the Miranda Rift, G. David Nordley

The Rest is Speculation, Eric Brown

Vacuum States, Geoffrey A. Landis

Permission to use the stories in this anthology has been granted as follows:

“The Pevatron Rats” © 2009 by Stephen Baxter. First publication, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“A Dance to Strange Musics” © 1998 by Gregory Benford. First published in Science Fiction Age, November 1998. Reprinted by

permission of the author.

“The Hole in the Hole” © 1994 by Terry Bisson. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, February 1994. Reprinted by

permission of the author.

“Bridge” © 1952 by James Blish. First published in Astounding Science Fiction, February 1952. Incorporated in They Shall Have

Stars (Faber, 1956) and subsequently in Cities in Flight (Avon, 1970), currently in print from Victor Gollancz. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate, the estate’s

literary agent, Heather Chalcroft, and Orion Publishing, Ltd.

“Hotrider” © 1991 by Keith Brooke. First published in Aboriginal Science Fiction, December 1991. Reprinted by permission of the

author.

“The Rest is Speculation” © 2009 by Eric Brown. First publication, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“Out of the Sun” © 1957 by Arthur C. Clarke. First published in If, February 1958. Reprinted by permission of the author’s

agents, Scovil Chichak Galen Literary Agency, Inc., New York.

“The Edge of the Map” © 2006 by Ian Creasey. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, June 2006. Reprinted by

permission of the author.

“Palindromic” © 1997 by Peter Crowther. First published in First Contact, edited by Martin H. Greenberg & Larry Segriff (New

York: Daw Books, 1997). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Waves and Smart Magma” © 2009 by Paul Di Filippo. First publication, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the

author.

“Vacuum States” © 1988 by Geoffrey A. Landis. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, July 1988. Reprinted by

permission of the author.

“Into the Miranda Rift” © 1993 by G. David Nordley. First published in Analog Science Fiction, July 1993. Reprinted by

permission of the author.

“Castle in the Sky” © 2009 by Robert Reed. First publication, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“Tiger Burning” © 2006 by Alastair Reynolds. First published in forbidden Planets, edited by Peter Crowther (New York: DAW

Books, 2006). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Anhedonia” © 2009 by Adam Roberts. First publication, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“Our Lady of the Sauropods” © 1980 by Robert Silverberg. First published in Omni, September 1980. Reprinted by permission of the

author.

“Mother Grasshopper” © 1997 by Michael Swanwick. First published in Geography of Unknown Lands (Lemoyne, PA: Tigereyes, 1997).

Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Black Hole Passes” © 1975 by John Varley. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, June 1975.

Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Width of the World” © 1983 by Ian Watson. First published in Universe 13, edited by Terry Carr (New York: Doubleday, 1983).

Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Peacock King” © 1965 by Ted White and Larry McCombs. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction,

November 1965. Reprinted by permission of Ted White on behalf of the authors.

“Cascade Point” © 1983 by Timothy Zahn. First published in Analog Science Fiction, December 1983. Reprinted by permission of the

author’s agents, Scovil Chichak Galen Literary Agency, Inc., New York.

What was it that first attracted you to science fiction? Or, if this is the first time you’ve thought of checking out a science-fiction anthology,

what are you hoping for?

I’ll tell you what first hooked me on science fiction: its ability to evoke a sense of wonder. Science fiction is a good medium for a number of things – satire, prediction,

adventure, invention . . . but these can also be delivered by other forms of fiction. If there’s one thing that science fiction has that towers above all other types of fiction, it is that

sense of wonder.

But what is the “sense of wonder”. If you’ve experienced it, you’ll know exactly what it is, but it isn’t so easy to put into words. To me, it’s that moment

when the story flicks a switch in your mind and opens new doors and perceptions, allowing you to appreciate things in a different and remarkable way. It’s especially pertinent in

demonstrating the potential of science or technology, the wonders that may be discovered in the depths of space or in the far future or deep within the human spirit.

That sense of wonder once defined science fiction: the wonders that science might bring. Unfortunately, as we all learned with the coming of the nuclear age, science could bring as much horror

as it could wonder, and, for some, science fiction lost that glow. These days it tends to be associated with the earliest forms of science fiction, particularly in the American pulp magazines, when

the spirit of science fiction was still young. But, while the spark of wonder may have dimmed in certain regions of science fiction, it has not expired. It’s still there, if you know where to

look.

And that’s what I wanted to do in this anthology: to show that the spirit of wonder can still be discovered in the science fiction of the recent years.

This anthology brings together twenty-one mindblowing stories – two of them full-length novellas – that will allow you, once more, to experience that sense of wonder. Much like

beauty is in the eye of the beholder, I can’t guarantee that every story will ignite that spark for you, as they do for me, but I’d be surprised if most don’t. Here are some of

the concepts you will encounter:

a discovery on the Moon that allows us to revisit our past

distances across the world suddenly expand and people vanish in between

explorers trapped under the surface of an alien world where the only way out is down

a future where death has been eradicated but returns to fulfil its destiny

the very last moments on planet Earth and the fate of the last inhabitants

And a lot more besides. For the most part I’ve selected stories from the last ten or twenty years, but I chose two older stories, both from the 1950s, to show how that sense of wonder

compares with more recent material. Those stories are by Arthur C. Clarke and James Blish, two authors whose work was always vibrant with wonder. There are also five new stories, written

specially for this anthology, which bring new twists and turns to the wonders of science and humanity.

One side-effect, indeed a major benefit, of that sense of wonder, is that these stories are, for the most part, uplifting and positive. They may at first seem to deal with difficult subjects and

problems, but opening the mind allows new ideas and solutions to be generated. Science fiction at its best makes you think about the world and ourselves, and when it does it in a positive way, it

encourages us to look beyond. So in selecting these stories I wanted ones that not only blew the mind, but left us with a glow of satisfaction and delight and, of course, wonder.

Here’s science fiction doing what it does best.

Mike Ashley

If there is one writer whose work epitomizes that sense of wonder, it is without doubt, Arthur C. Clarke. It’s almost impossible to read any of his stories or

novels without experiencing that trigger-moment when the mind expands to take in an awe-inspiring concept. Along with Stanley Kubrick, he achieved it magnificently in the film 2001: A Space

Odyssey. It’s there in his novels Childhood’s End, The City and the Stars, Rendezvous with Rama and his short stories “The Star”, “Jupiter V” and

“The Nine Billion Names of God” – possibly the definitive “sense-of-wonder” story. For this anthology I wanted to choose a lesser known story, but one that still

packs a considerable punch – even though it’s the shortest story in the book. (Well, the last story is the same length.) Clarke had that ability to develop a remarkable, near

transcendental idea, in just a few words – and deliver an idea that will remain with you ever after.

I was much saddened upon learning of Clarke’s death in March 2008, while I was assembling this volume. His death brought to an end a significant chapter in the history of science

fiction – but it was only a chapter. Clarke would be the first to emphasize that the story continues – and that’s why he opens this anthology.

IF YOU HAVE ONLY LIVED on Earth, you have never seen the sun. Of course, we could not look at it directly, but only through

dense filters that cut its rays down to endurable brilliance. It hung there forever above the low, jagged hills to the west of the Observatory neither rising nor setting, yet moving around a small

circle in the sky during the eighty-eight-day year of our little world. For it is not quite true to say that Mercury keeps that same face always turned toward the sun; it wobbles slightly on its

axis, and there is a narrow twilight belt which knows such terrestrial commonplaces as dawn and sunset.

We were on the edge of the twilight zone, so that we could take advantage of the cool shadows yet could keep the sun under continuous surveillance as it hovered there above the hills. It was a

full-time job for fifty astronomers and other assorted scientists; when we’ve kept it up for a hundred years or so, we may know something about the small star that brought life to Earth.

There wasn’t a single band of solar radiation that someone at the Observatory had not made a life’s study and was watching like a hawk. From the far X rays to the longest of radio

waves, we had set our traps and snares; as soon as the sun thought of something new, we were ready for it. So we imagined . . .

The sun’s flaming heart beats in a slow, eleven-year rhythm, and we were near the peak of the cycle. Two of the greatest spots ever recorded – each of them large enough to swallow a

hundred Earths – had drifted across the disk like great black funnels piercing deeply into the turbulent outer layers of the sun. They were black, of course, only by contrast with the

brilliance all around them; even their dark, cool cores were hotter and brighter than an electric arc. We had just watched the second of them disappear around the edge of the disk, wondering if it

would survive to reappear two weeks later, when something blew up on the equator.

It was not too spectacular at first, partly because it was almost exactly beneath us – the precise center of the sun’s disk – and so was merged into all the activity around it.

If it had been near the edge of the sun, and thus projected against the background of space, it would have been truly awe-inspiring.

Imagine the simultaneous explosion of a million H-bombs. You can’t? Nor can anyone else but that was the sort of thing we were watching climb up toward us at hundreds of miles a second,

straight out of the sun’s spinning equator. At first it formed a narrow jet, but it was quickly frayed around the edges by the magnetic and gravitational forces that were fighting against it.

The central core kept right on, and it was soon obvious that it had escaped from the sun completely and was headed out into space – with us as its first target.

Though this had happened half a dozen times before, it was always exciting. It meant that we could capture some of the very substance of the sun as it went hurtling past in a great cloud of

electrified gas. There was no danger; by the time it reached us it would be far too tenuous to do any damage, and, indeed, it would take sensitive instruments to detect it at all.

One of those instruments was the Observatory’s radar, which was in continual use to map the invisible ionized layers that surround the sun for millions of miles. This was my department; as

soon as there was any hope of picking up the oncoming cloud against the solar background, I aimed my giant radio mirror toward it.

It came in sharp and clear on the long-range screen – a vast, luminous island still moving outward from the sun at hundreds of miles a second. At this distance it was impossible to see its

finer details, for my radar waves were taking minutes to make the round trip and to bring me back the information they were presenting on the screen. Even at its speed of not far short of a million

miles an hour, it would be almost two days before the escaping prominence reached the orbit of Mercury and swept past us toward the outer planets. But neither Venus nor Earth would record its

passing, for they were nowhere near its line of flight.

The hours drifted by; the sun had settled down after the immense convulsion that had shot so many millions of tons of its substance into space, never to return. The aftermath of that eruption

was now a slowly twisting and turning cloud a hundred times the size of Earth, and soon it would be close enough for the short-range radar to reveal its finer structure.

Despite all the years I have been in the business, it still gives me a thrill to watch that line of light paint its picture on the screen as it spins in synchronism with the narrow beam of radio

waves from the transmitter. I sometimes think of myself as a blind man exploring the space around him with a stick that may be a hundred million miles in length. For man is truly blind to the

things I study; these great clouds of ionized gas moving far out from the sun are completely invisible to the eye and even to the most sensitive of photographic plates. They are ghosts that briefly

haunt the solar system during the few hours of their existence; if they did not reflect our radar waves or disturb our magnetometers, we should never know that they were there.

The picture on the screen looked not unlike a photograph of a spiral nebula, for as the cloud slowly rotated it trailed ragged arms of gas for ten thousand miles around it. Or it might have been

a terrestrial hurricane that I was watching from above as it spun through the atmosphere of Earth. The internal structure was extremely complicated, and was changing minute by minute beneath the

action of forces which we have never fully understood. Rivers of fire were flowing in curious paths under what could only be the influence of electric fields; but why were they appearing from

nowhere and disappearing again as if matter was being created and destroyed? And what were those gleaming nodules, larger than the moon, that were being swept along like boulders before a

flood?

Now it was less than a million miles away; it would be upon us in little more than an hour. The automatic cameras were recording every complete sweep of the radar scan, storing up evidence which

was to keep us arguing for years. The magnetic disturbance riding ahead of the cloud had already reached us; indeed, there was hardly an instrument in the Observatory that was not reacting in some

way to the onrushing apparition.

I switched to the short-range scanner, and the image of the cloud expanded so enormously that only its central portion was on the screen. At the same time I began to change frequency, tuning

across the spectrum to differentiate among the various levels. The shorter the wave length, the farther you can penetrate into a layer of ionized gas; by this technique I hoped to get a kind of

X-ray picture of the cloud’s interior.

It seemed to change before my eyes as I sliced down through the tenuous outer envelope with its trailing arms, and approached the denser core. “Denser”, of course, was a purely

relative word; by terrestrial standards even its most closely packed regions were still a fairly good vacuum. I had almost reached the limit of my frequency band, and could shorten the wave length

no farther, when I noticed the curious, tight little echo not far from the center of the screen.

It was oval, and much more sharp-edged than the knots of gas we had watched adrift in the cloud’s fiery streams. Even in that first glimpse, I knew that here was something very strange and

outside all previous records of solar phenomena. I watched it for a dozen scans of the radar beam, then called my assistant away from the radiospectrograph, with which he was analyzing the

velocities of the swirling gas as it spun toward us.

“Look, Don,” I asked him, “have you ever seen anything like that?”

“No,” he answered after a careful examination. What holds it together? It hasn’t changed its shape for the last two minutes.”

“That’s what puzzles me. Whatever it is, it should have started to break up by now, with all that disturbance going on around it. But it seems as stable as ever.”

“How big would you say it is?”

I switched on the calibration grid and took a quick reading.

“It’s about five hundred miles long, and half that in width.”

“Is this the largest picture you can get?”

“I’m afraid so. We’ll have to wait until it’s closer before we can see what makes it tick.”

Don gave a nervous little laugh.

“This is crazy,” he said, “but do you know something? I feel as if I’m looking at an amoeba under a microscope.”

I did not answer; for, with what I can only describe as a sensation of intellectual vertigo, exactly the same thought had entered my mind.

We forgot about the rest of the cloud, but luckily the automatic cameras kept up their work and no important observations were lost. From now on we had eyes only for that sharp-edged lens of gas

that was growing minute by minute as it raced toward us. When it was no farther away than is the moon from Earth, it began to show the first signs of its internal structure, revealing a curious

mottled appearance that was never quite the same on two successive sweeps of the scanner.

By now, half the Observatory staff had joined us in the radar room, yet there was complete silence as the oncoming enigma grew swiftly across the screen. It was coming straight toward us; in a

few minutes it would hit Mercury somewhere in the center of the daylight side, and that would be the end of it – whatever it was. From the moment we obtained our first really detailed view

until the screen became blank again could not have been more than five minutes; for every one of us, that five minutes will haunt us all our lives.

We were looking at what seemed to be a translucent oval, its interior laced with a network of almost invisible lines. Where the lines crossed there appeared to be tiny, pulsing nodes of light;

we could never be quite sure of their existence because the radar took almost a minute to paint the complete picture on the screen – and between each sweep the object moved several thousand

miles. There was no doubt, however, that the network itself existed; the cameras settled any arguments about that.

So strong was the impression that we were looking at a solid object that I took a few moments off from the radar screen and hastily focused one of the optical telescopes on the sky. Of course,

there was nothing to be seen – no sign of anything silhouetted against the sun’s pock-marked disk. This was a case where vision failed completely and only the electrical senses of the

radar were of any use. The thing that was coming toward us out of the sun was as transparent as air – and far more tenuous.

As those last moments ebbed away, I am quite sure that every one of us had reached the same conclusion – and was waiting for someone to say it first. What we were seeing was impossible,

yet the evidence was there before our eyes. We were looking at life, where no life could exist . . .

The eruption had hurled the thing out of its normal environment, deep down in the flaming atmosphere of the sun. It was a miracle that it had survived its journey through space; already it must

be dying, as the forces that controlled its huge, invisible body lost their hold over the electrified gas which was the only substance it possessed.

Today, now that I have run through those films a hundred times, the idea no longer seems so strange to me. For what is life but organized energy? Does it matter what form that energy

takes – whether it is chemical, as we know it on Earth, or purely electrical, as it seemed to be here? Only the pattern is important; the substance itself is of no significance. But at the

time I did not think of this; I was conscious only of a vast and overwhelming wonder as I watched this creature of the sun live out the final moments of its existence.

Was it intelligent? Could it understand the strange doom that had befallen it? There are a thousand such questions that may never be answered. It is hard to see how a creature born in the fires

of the sun itself could know anything of the external universe, or could even sense the existence of something as unutterably cold as rigid nongaseous matter. The living island that was falling

upon us from space could never have conceived, however intelligent it might be, of the world it was so swiftly approaching

Now it filled our sky – and perhaps, in those last few seconds, it knew that something strange was ahead of it. It may have sensed the far-flung magnetic field of Mercury, or felt the tug

of our little world’s gravitational pull. For it had begun to change; the luminous lines that must have been what passed for its nervous system were clumping together in new patterns, and I

would have given much to know their meaning. It may be that I was looking into the brain of a mindless beast in its last convulsion of fear – or of a godlike being making its peace with

universe.

Then the radar screen was empty, wiped clean during a single scan of the beam. The creature had fallen below our horizon and was hidden from us now by the curve of the planet. Far out in the

burning dayside of Mercury, in the inferno where only a dozen men have ever ventured and fewer still come back alive, it smashed silently and invisibly against the seas of molten metal, the hills

of slowly moving lava. The mere impact could have meant nothing to such an entity; what it could not endure was its first contact with the inconceivable cold of solid matter.

Yes, cold. It had descended upon the hottest spot in the solar system, where the temperature never falls below seven hundred degrees Fahrenheit and sometimes approaches a thousand. And

that was far, far colder to it than the antarctic winter would be to a naked man.

We did not see it die, out there in the freezing fire; it was beyond the reach of our instruments now, and none of them recorded its end. Yet every one of us knew when that moment came, and that

is why we are not interested when those who have seen only the films and tapes tell us that we were watching some purely natural phenomenon.

How can one explain what we felt, in that last moment when half our little world was enmeshed in the dissolving tendrils of that huge but immaterial brain? I can only say that it was a soundless

cry of anguish, a death pang that seeped into our minds without passing through the gateways of the senses. Not one of us doubted then, or has ever doubted since, that he had witnessed the passing

of a giant.

We may have been both the first and the last of all men to see so mighty a fall. Whatever they may be, in their unimaginable world within the sun, our paths and theirs may never cross

again. It is hard to see how we can ever make contact with them, even if their intelligence matches ours.

And does it? It may be well for us if we never know the answer. Perhaps they have been living there inside the sun since the universe was born, and have climbed to peaks of wisdom that we shall

never scale. The future may be theirs, not ours; already they may be talking across the light-years to their cousins in other stars.

One day they may discover us, by whatever strange senses they possess, as we circle around their mighty, ancient home, proud of our knowledge and thinking ourselves lords of creation. They may

not like what they find, for to them we should be no more than maggots, crawling upon the skins of worlds too cold to cleanse themselves from the corruption of organic life.

And then, if they have the power, they will do what they consider necessary. The sun will put forth its strength and lick the faces of its children; and thereafter the planets will go their way

once more as they were in the beginning – clean and bright . . . and sterile.

Stephen Baxter (b. 1957) collaborated with Arthur C. Clar

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...