- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

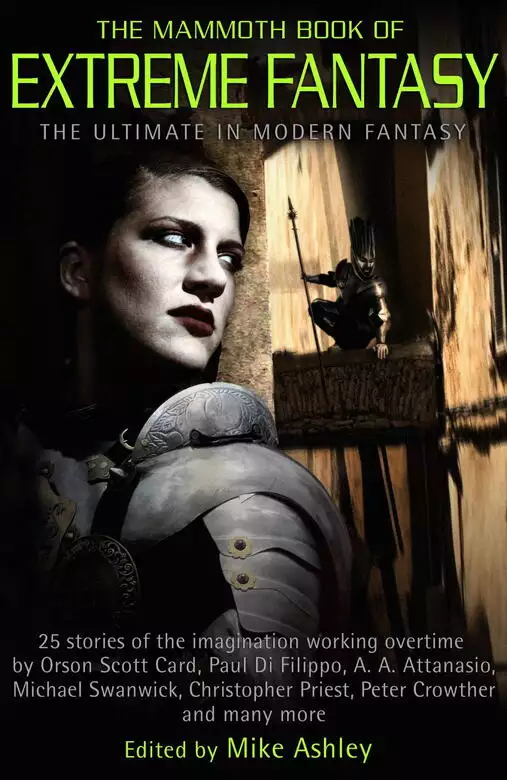

In extreme fantasy anything can happen. In Mike Ashley's breathtaking new anthology the only rules are those the writer makes - these are stories to liberate both the writers' and readers' imagination. They will take you to hell and back (literally - two of the stories involve hell in ways never explored before).

For too long fantasy fiction has become synonymous with vast heroic-fantasy adventures in imitation of The Lord of the Rings, but the genre has always been far greater than dwarves and elves. Today many writers are rediscovering the wider world of fantasy and creating bold new ideas or magically reworking older arts.

Ashley selects 25 stories by the likes of Orson Scott Card, Paul Di Filippo, A. A. Attanasio, Michael Swanwick, Christopher Priest and Peter Crowther, arranged in ascending order of 'extremeness'.

The anthology opens with a story that takes us beyond Middle Earth in 'Senator Bilbo' by Andy Duncan - showing what happens when a radical descendant of his famous namesake tries to introduce immigration control - and reaches the ultimate in 'The Dark One' by A. A. Attanasio, a rite of passage story where you, the reader, discover you are being tested to become the successor to Satan.

Other stories include:

A man with a terminal disease looks for a cure in a world where Edward Lear meets Lewis Carroll.

A man decides to banish all language.

A tour of Hell by the boatman himself.

The great comic stars of Hollywood find themselves seeking their lost world.

A magical experiment recreates the Crucifixion.

Suddenly all colour drains out of the world.

A magical recreation of Chinese fantasy cinema where a magician and his adepts fight the flying dead.

Release date: August 4, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Extreme Fantasy

Mike Ashley

The Mammoth Book of 20th Century Science Fiction

The Mammoth Book of Best New Erotica 7

The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror 18

The Mammoth Book of Best New Manga

The Mammoth Book of Best New Manga 2

The Mammoth Book of Best New SF 20

The Mammoth Book of Best War Comics

The Mammoth Book of Bikers

The Mammoth Book of Celtic Myths and Legends

The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Comic Quotes

The Mammoth Book of CSI

The Mammoth Book of the Deep

The Mammoth Book of Dickensian Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Dirty, Sick, X-Rated & Politically Incorrect Jokes

The Mammoth Book of the Edge

The Mammoth Book of Erotic Women

The Mammoth Book of Extreme Science Fiction

The Mammoth Book of the Funniest Cartoons of All Time

The Mammoth Book of Great Detective Stories

The Mammoth Book of Great Inventions

The Mammoth Book of Haunted House Stories

The Mammoth Book of Insults

The Mammoth Book of International Erotica

The Mammoth Book of IQ Puzzles

The Mammoth Book of Jacobean Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Jokes

The Mammoth Book of Killers at Large

The Mammoth Book of King Arthur

The Mammoth Book of Lesbian Erotica

The Mammoth Book of Modern Ghost Stories

The Mammoth Book of Monsters

The Mammoth Book of Mountain Disasters

The Mammoth Book of New Jules Verne Adventures

The Mammoth Book of New Terror

The Mammoth Book of On the Road

The Mammoth Book of Perfect Crimes and Impossible Mysteries

The Mammoth Book of Pirates

The Mammoth Book of Polar Journeys

The Mammoth Book of Roaring Twenties Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Roman Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Secret Code Puzzles

The Mammoth Book of Sex, Drugs & Rock ’n’ Roll

The Mammoth Book of Sorcerers’ Tales

The Mammoth Book of Space Exploration and Disasters

The Mammoth Book of Special Forces

The Mammoth Book of Special Ops

The Mammoth Book of Sudoku

The Mammoth Book of Travel in Dangerous Places

The Mammoth Book of True Crime

The Mammoth Book of True War Stories

The Mammoth Book of Unsolved Crimes

The Mammoth Book of Vampires

The Mammoth Book of Wild Journeys

The Mammoth Book of Women Who Kill

The Mammoth Book of the World’s Greatest Chess Games

The following stories are in copyright in the names of the individual authors or their estates.

“The Dark One: A Mythograph” © 1994 by A A Attanasio. First published in Crank #4, 1994. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Lost Wax” © 2006 by Leah Bobet. First published in Realms of Fantasy, December 2006. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Sandmagic” © 1979 by Orson Scott Card. First published in Swords Against Darkness IV edited by Andrew J Offutt (Zebra Books, 1979). Reprinted by

permission of the author.

“Tower of Babylon” © 1990 by Ted Chiang. First published in Omni, November 1990. From the authors collection, Stories of Your Life and Others

(Tor, 2002). Reprinted by permission of the author and the authors agents, the Virginia Kidd Agency, Inc.

“Dream a Little Dream for Me…” © 2000 by Peter Crowther. First published in Perchance to Dream edited by Denise Little and Martin H Greenberg

(DAW Books, 2000). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Jack Neck and the Worry Bird” © 1998 by Paul Di Filippo. First published in Science Fiction Age, July 1998. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Senator Bilbo” © 2001 by Andy Duncan. First published in Starlight 3 edited by Patrick Nielsen Hayden (Tor Books, 2001). Reprinted by permission of the

author.

“Boatman’s Holiday” © 2005 by Jeffrey Ford. First published in The Book of Voices edited by Michael Butscher (Flame Books, 2005). Reprinted by

permission of the author.

“The Fence at the End of the World” © 2002 by Melissa Mia Hall. First published in Realms of Fantasy, August 2002. Reprinted by permission of the

author.

“The Old House Under the Snow” © 2004 by Rhys Hughes. First published in Postscripts #2, Summer 2004. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The All-at-Once Man” © 1970, 1998 by the Estate of R A Lafferty. First published in Galaxy Magazine, July 1970. Reprinted by permission of the Estate

and the Estates Agents, Virginia Kidd Agency, Inc.

“Using It and Losing It” © 1990 by Jonathan Lethem. First published in Journal Wired, Summer/Fall 1990. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Charlie the Purple Giraffe was Acting Strangely” © 2004 by David D Levine. First published in Realms of Fantasy, June 2004. Reprinted by permission of

the author.

“A Ring of Green Fire” © 1994 by Sean McMullen. First published in Interzone #89, November 1994. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Elric at the End of Time” © 1981 by Michael Moorcock. First published in Elsewhere, edited by Terri Windling and Mark Alan Arnold (Ace Books, 1981).

Reprinted by permission of the author.

“I Am Bonaro” © 1964 by John Niendorff. First published in Fantastic, December 1964. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Master Lao and the Flying Horror” © 2005 by Lawrence Person. First published in Postscripts #4, Summer 2005. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Cup and Table” © 2006 by Tim Pratt. First published in Twenty Epics, edited by Susan Groppi and David Moles (Lulu.com,

2006). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“I, Haruspex” © 1998 by Christopher Priest. First published in The Third Alternative #16, 1998. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Detweiler Boy” © 1977, 2005 by the Estate of Tom Reamy First published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction April 1977. Reprinted by

permission of the Estate and the Estates Agents, Virginia Kidd Agency, Inc.

“Radio Waves” © 1995 by Michael Swanwick. First published in Omni, Winter 1995. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Save a Place in the Lifeboat for Me” © 1976 by Howard Waldrop. First published in Nickelodeon #2, September 1976. Reprinted by permission of the

author.

“Banquet of the Lords of Night” © 2002 by Liz Williams. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, June 2002. Reprinted by permission of the

author.

IN MY PREVIOUS ANTHOLOGY, The Mammoth Book of Extreme Science Fiction, I defined “extreme” as those stories that took a basic

idea, whether simple or complicated, and developed it to some extreme, beyond what the reader might normally expect. I’ve used that same basis here.

However, whereas the content of a science fiction story is limited by the rules of science (no matter how much the author may try and bend them), in fantasy there are no limits other than those

which the writer himself may impose. So while science fiction is the literature of the possible, no matter how extreme, fantasy is the literature of the impossible, which means it’s pretty

extreme to start with.

And that’s the fun of this anthology. In all of the stories, the authors have taken a fantastic idea – and I mean fantastic in both its senses – and then seen how far they can

push it. My one criterion is that they must still be readable stories. I did not want anything that was incomprehensible.

All the stories here are straight narratives. It’s the ideas and how they are developed that are extreme, and though the authors have applied a certain logic as a hand-brake on their

imagination, that doesn’t stop them taking things beyond the impossible.

The kind of ideas you will encounter include:

And those are the relatively straightforward ones.

In recent years, ever since the phenomenal success of Lord of the Rings, fantasy has become associated in many peoples minds as relating solely to wizards and elves and

dwarves in worlds where magic works. This overlooks that vast wealth of fantasy fiction that has been appearing for centuries, much of which has nothing to do with elves or fairies.

Fantasy is the most liberated form of fiction. It allows the writer to free their own and the readers’ imaginations and go for broke. In fantasy anything can happen, anything at all. In

fantasy reality gives way to the unreal.

The challenge to the writer is to make it into a meaningful story which the reader can still understand and which could even seem real, no matter how extreme. There are stories here, even the

most extreme ones, which manage to suspend the readers disbelief enough that, for a moment, you believe it could happen. And that’s one of the pleasures of fantasy. For that moment as the

story engulfs you, you can live in the world of the impossible. Masters of fantasy in the past have included H G Wells, John Collier, Algernon Blackwood, H P Lovecraft and Stephen Vincent Benet

– none of whom wrote about elves and fairies. However, for this volume I wanted to include stories primarily by the modern masters. Over half the stories have been written in the past ten

years. The oldest story is by William Hope Hodgson who was so forward thinking that the story reads as almost contemporary. Contributors include those masters of the unusual and bizarre Orson Scott

Card, Peter Crowther, Paul Di Filippo, Rhys Hughes, R A Lafferty, Michael Moorcock, Christopher Priest, Michael Swanwick and Howard Waldrop.

As with the previous volume I have presented the stories in sequence from the least to the most extreme, so your imagination can expand as you work through the book. Dip in at a later story at

your peril! However, in order to bring you back safely into this world the final story serves as a form of digestif, allowing a mental calming down. But otherwise, the brakes are off.

Prepare yourself for a wild and exuberant ride.

Mike Ashley

November 2007

We begin our journey in what ought to be the relative safety of the Shire. But we are generations on from the days of Bilbo and Frodo and the Shire finds itself

infected by politics and politicians. Andy Duncan wondered what it might be like if Theodore Bilbo, the segregationist and member of the Ku Klux Klan, who was a US senator from 1935 to 1947,

had been related to Bilbo Baggins.

Andy Duncan (b. 1964) is a native of South Carolina. He is a former journalist and currently a college teacher who has been winning a swathe of awards since his first fiction appeared

in 1996, including the World Fantasy Award for his collection Belthahatchie and Other Stories (2000). His website is at www.angelfire.com/al/andyduncan/

“It regrettably has become necessary for us now, my friends, to consider seriously and to discuss openly the most pressing question facing

our homeland since the War. By that I mean, of course, the race question.”

In the hour before dawn, the galleries were empty, and the floor of the Shire-moot was nearly so. Scattered about the chamber, a dozen or so of the Senator’s allies – a few more than

needed to maintain the quorum, just to be safe – lounged at their writing-desks, feet up, fingers laced, pipes stuffed with the best Bywater leaf, picnic baskets within reach: veterans, all.

Only young Appledore from Bridge Inn was snoring and slowly folding in on himself; the chestnut curls atop his head nearly met those atop his feet. The Senator jotted down Appledore’s name

without pause. He could get a lot of work done while making speeches – even a filibuster nine hours long (and counting).

“There are forces at work today, my friends, without and within our homeland, that are attempting to destroy all boundaries between our proud, noble race and all the mule-gnawing,

cave-squatting, light-shunning, pit-spawned scum of the East.”

The Senator’s voice cracked on “East,” so he turned aside for a quaff from his (purely medicinal) pocket flask. His allies did not miss their cue. “Hear, hear,”

they rumbled, thumping the desktops with their calloused heels. “Hear, hear.”

“This latest proposal,” the Senator continued, “this so-called immigration bill – which, as I have said, would force even our innocent daughters to suffer the reeking

lusts of all the ditch-bred legions of darkness – why, this baldfooted attempt originated where, my friends?”

“Buckland!” came the dutiful cry.

“Why, with the delegation from Buckland…long known to us all as a hotbed of book-mongers, one-Earthers, elvish sympathizers, and other off-brands of the halfling

race.”

This last was for the benefit of the newly arrived Fredegar Bracegirdle, the unusually portly junior member of the Buckland delegation. He huffed his way down the aisle, having drawn the short

straw in the hourly backroom ritual.

“Will the distinguished Senator,” Bracegirdle managed to squeak out, before succumbing to a coughing fit. He waved his bladder-like hands in a futile attempt to disperse the thick

purplish clouds that hung in the chamber like the vapors of the Eastmarsh. Since a Buckland-sponsored bill to ban tobacco from the floor had been defeated by the Senator three Shire-moots previous,

his allies’ pipe-smoking had been indefatigable. Finally Bracegirdle sputtered: “Will the distinguished Senator from the Hill kindly yield the floor?”

In response, the Senator lowered his spectacles and looked across the chamber to the Thain of the Shire, who recited around his tomato sandwich: “Does the distinguished Senator from the

Hill so yield?”

“I do not,” the Senator replied, cordially.

“The request is denied, and the distinguished Senator from the Hill retains the floor,” recited the Thain of the Shire, who then took another hearty bite of his sandwich. The

Senator’s party had re-written the rules of order, making this recitation the storied Thain’s only remaining duty.

“Oh, hell and hogsheads,” Bracegirdle muttered, already trundling back up the aisle. As he passed Gorhendad Bolger from the Brockenborings, that Senators man like his father before

him kindly offered Bracegirdle a pickle, which Bracegirdle accepted with ill grace.

“Now that the distinguished gentleman from the Misty Mountains has been heard from,” the Senator said, waiting for the laugh, “let me turn now to the evidence – the

overwhelming evidence, my friends – that many of the orkish persuasion currently living among us have been, in fact, active agents of the Dark Lord…

As the Senator plowed on, seldom referring to his notes, inventing statistics and other facts as needed, secure that this immigration bill, like so many bills before it, would wither and die

once the Bucklanders’ patience was exhausted, his self-confidence faltered only once, unnoticed by anyone else in the chamber. A half-hour into his denunciation of the orkish threat, the

Senator noticed a movement – no, more a shift of light, a glimmer - in the corner of his eye. He instinctively turned his head towards the source, and saw, or thought he saw,

sitting in the farthest, darkest corner of the otherwise empty gallery, a man-sized figure in a cloak and pointed hat, who held what must have been (could have been) a staff; but in the next

blink, that corner held only shadows, and the Senator dismissed the whatever-it-was as a fancy born of exhilaration and weariness. Yet he was left with a lingering chill, as if (so his old mother,

a Took, used to say) a dragon had hovered over his grave.

At noon, the Bucklanders abandoned their shameful effort to open the High Hay, the Brandywine Bridge, and the other entry gates along the Bounds to every misbegotten so-called

“refugee,” be he halfling, man, elf, orc, warg, Barrow-wight, or worse. Why, it would mean the end of Shire culture, and the mongrelization of the halfling race! No, sir! Not today

– not while the Senator was on the job.

Triumphant but weary, the champion of Shire heritage worked his way, amid a throng of supplicants, aides, well-wishers, reporters, and yes-men, through the maze of tunnels that led to his

Hill-side suite of offices. These were the largest and nicest of any senators, with the most pantries and the most windows facing the Bywater, but they also were the farthest from the Shire-moot

floor. The Senator’s famous ancestor and namesake had been hale and hearty even in his eleventy-first year; the Senator, pushing ninety, was determined to beat that record. But every time he

left the chamber, the office seemed farther away.

“Gogluk carry?” one bodyguard asked.

“Gogluk not carry,” the Senator retorted. The day he’d let a troll haul him through the corridors like luggage would be the day he’d sailed oversea for good.

All the Senator’s usual tunnels had been enlarged to accommodate the bulk of his two bodyguards, who nevertheless had to stoop, their scaly shoulders scraping the ceiling. Loyal,

dim-witted, and huge – more than five feet in height – the Senator’s trolls were nearly as well known in the Shire as the Senator himself, thanks partially to the Senator’s

perennial answer to a perennial question from the press at election time: “Racist? Me? Why, I love Gogluk and Grishzog, here, as if they were my own flesh and blood, and they love me just the

same, don’t you, boys? See? Here, boys, have another biscuit.”

Later, once the trolls had retired for the evening, the Senator would elaborate. Trolls, now, you could train them, they were teachable; they had their uses, same as those swishy elves, who were

so good with numbers. Even considered as a race, the trolls weren’t much of a threat – no one had seen a baby troll in ages. But those orcs? They did nothing but breed.

Carry the Senator they certainly did not, but by the time the trolls reached the door of the Senator’s outermost office (no mannish rectangular door, but a traditional Shire-door, round

and green with a shiny brass knob in the middle), they were virtually holding the weary old halfling upright and propelling him forward, like a child pushed to kiss an ugly aunt.

Only the Senator’s mouth was tireless. He continued to greet constituents, compliment babies, rap orders to flunkies, and rhapsodise about the glorious inheritance of the Shire as the

procession squeezed its way through the increasingly small rooms of the Senator’s warren-like suite, shedding followers like snakeskin. The only ones who made it from the innermost outer

office to the outermost inner office were the Senator, the trolls, and four reporters, all of whom considered themselves savvy under-Hill insiders for being allowed so far into the great

man’s sanctum.

The Senator further graced these reporters by reciting the usual answers to the usual questions as he looked through his mail, pocketing the fat envelopes and putting the thin ones in a pile for

his intern, Miss Boffin. The Senator got almost as much work done during press conferences as during speeches.

“Senator, some members of the Buckland delegation have insinuated, off the record, that you are being investigated for alleged bribe-taking. Do you have a comment?”

“You can tell old Gerontius Brownlock that he needn’t hide behind a façade of anonymity, and further that I said he was begotten in an orkish graveyard at midnight, suckled by

a warg-bitch and educated by a fool. That’s off the record, of course.”

“Senator, what do you think of your chances for re-election next fall?”

“The only time I have ever been defeated in a campaign, my dear, was my first one. Back when your grandmother was a whelp, I lost a clerkship to a veteran of the Battle of Bywater. A

one-armed veteran. I started to vote for him myself. But unless a one-armed veteran comes forward pretty soon, little lady, I’m in no hurry to pack.”

The press loved the Senator. He was quotable, which was all the press required of a public official.

“Now, gentle folk, ladies, the business of the Shire awaits. Time for just one more question.”

An unfamiliar voice aged and sharp as Mirkwood cheese rang out:

“They say your ancestor took a fairy wife.”

The Senator looked up, his face even rounder and redder than usual. The reporters backed away. “It’s a lie!” the Senator cried. “Who said such a thing? Come, come. Who

said that?”

“Said what, Senator?” asked the most senior reporter (Bracklebore, of the Bywater Battle Cry), his voice piping as if through a reed. “I was just asking about the

quarterly sawmill-production report. If I may continue…”

“Goodbye,” said the Senator. On cue, the trolls snatched up the reporters, tossed them into the innermost outer office, and slammed and locked the door. Bracklebore, ousted too

quickly to notice, finished his question in the next room, voice muffled by the intervening wood. The trolls dusted their hands.

“Goodbye,” said Gogluk – or was that Grishzog?

“Goodbye,” said Grishzog – or was that Gogluk?

Which meant, of course, “Mission accomplished, Senator,” in the pidgin Common Speech customary among trolls.

“No visitors,” snapped the Senator, still nettled by that disembodied voice, as he pulled a large brass key from his waistcoat-pocket and unlocked the door to his personal

apartments. Behind him, the trolls assumed position, folded their arms, and turned to stone.

“Imagination,” the Senator muttered as he entered his private tunnel.

“Hearing things,” he added as he locked the door behind.

“Must be tired,” he said as he plodded into the sitting-room, yawning and rubbing his hip.

He desired nothing more in all the earth but a draught of ale, a pipe, and a long snooze in his armchair, and so he was all the more taken aback to find that armchair already occupied by a

white-bearded Big Person in a tall pointed blue hat, an ankle-length gray cloak, and immense black boots, a thick oaken staff laid across his knees.

“’Struth!” the Senator cried.

The wizard – for wizard he surely was – slowly stood, eyes like lanterns, bristling gray brows knotted in a thunderous scowl, a meteor shower flashing through the weave of his cloak,

one gnarled index finger pointed at the Senator – who was, once the element of surprise passed, unimpressed. The meteor effect lasted only a few seconds, and thereafter the intruder was an

ordinary old man, though with fingernails longer and more yellow than most.

“Do you remember me?” the wizard asked. His voice crackled like burning husks. The Senator recognized that voice.

“Should I?” he retorted. “What’s the meaning of piping insults into my head? And spying on me in the Shire-moot? Don’t deny it; I saw you flitting about the

galleries like a bad dream. Come on, show me you have a tongue – else I’ll have the trolls rummage for it.” The Senator was enjoying himself; he hadn’t had to eject an

intruder since those singing elves occupied the outer office three sessions ago.

“You appointed me, some years back,” the wizard said, “to the University, in return for some localized weather effects on Election Day.”

So that was all. Another disgruntled officeholder. “I may have done,” the Senator snapped. “What of it?” The old-timer showed no inclination to reseat himself, so the

Senator plumped down in the armchair. Its cushions now stank of men. The Senator kicked the wizard’s staff from underfoot and jerked his leg back; he fancied something had nipped his toe.

The staff rolled to the feet of the wizard. As he picked it up, the wider end flared with an internal blue glow. He commenced shuffling about the room, picking up knickknacks and setting them

down again as he spoke.

“These are hard times for wizards,” the wizard rasped. “New powers are abroad in the world, and as the powers of wind and rock, water and tree are ebbing, we ebb with them.

Still, we taught our handfuls of students respect for the old ways. Alas, no longer!”

The Senator, half-listening, whistled through his eyeteeth and chased a flea across the top of his foot.

“The entire thaumaturgical department – laid off! With the most insulting of pensions! A flock of old men feebler than I, unable even to transport themselves to your chambers, as I

have wearily done – to ask you, to demand of you, why?”

The Senator yawned. His administrative purging of the Shire’s only university, in Michel Delving, had been a complex business with a complex rationale. In recent years, the faculty had got

queer Eastern notions into their heads and their classrooms – muddleheaded claims that all races were close kin, that orcs and trolls had not been separately bred by the Dark Power, that the

Dark Power’s very existence was mythical. Then the faculty quit paying the campaign contributions required of all public employees, thus threatening the Senator’s famed “Deduct

Box.” Worst of all, the faculty demanded “open admissions for qualified non-halflings,” and the battle was joined. After years of bruising politics, the Senator’s appointees

now controlled the university board, and a long-overdue housecleaning was underway. Not that the Senator needed to recapitulate all this to an unemployed spell-mumbler. All the Senator said

was:

“It’s the board that’s cut the budget, not me.” With a cry of triumph, he purpled a fingernail with the flea. “Besides,” he added, “they kept all the

popular departments. Maybe you could pick up a few sections of Heritage 101.”

This was a new, mandatory class that drilled students on the unique and superior nature of halfling culture and on the perils of immigration, economic development, and travel. The wizard’s

response was: “Pah!”

The Senator shrugged. “Suit yourself. I’m told the Anduin gambling-houses are hiring. Know any card tricks?”

The wizard stared at him with rheumy eyes, then shook his head. “Very well,” he said. “I see my time is done. Only the Grey Havens are left to me and my kind. We should have

gone there long since. But your time, too, is passing. No fence, no border patrol – not even you, Senator – can keep all change from coming to the Shire.”

“Oh, we can’t, can we?” the Senator retorted. As he got worked up, his Bywater accent got thicker. “We sure did keep those Bucklanders from putting over that so-called

Fair Distribution System, taking people’s hard-earned crops away and handing ’em over to lazy trash to eat. We sure did keep those ugly up-and-down man houses from being built all over

the Hill as shelter for immigrant rabble what ain’t fully halfling or fully human or fully anything. Better to be some evil race than no race at all.”

“There are no evil races,” said the wizard.

The Senator snorted. “I don’t know how you were raised, but I was raised on the Red Book of Westmarch, chapter and verse, and it says so right there in the Red Book, orcs are

mockeries of men, filthy cannibals spawned by the Enemy, bent on overrunning the world…

He went on in this vein, having lapsed, as he often did in conversation, into his tried-and-true stump speech, galvanized by the memories of a thousand cheering halfling crowds. “Oh,

there’s enemies everywhere to our good solid Shire-life,” he finally cried, punching the air, “enemies outside and inside, but we’ll keep on beating ’em back and

fighting the good fight our ancestors fought at the Battle of Bywater. Remember their cry:

“Awake! Awake! Fear, Fire, Foes! Awake!

“Fire, Foes! Awake!”

The cheers receded, leaving only the echo of his own voice in the Senator’s ears. His fists above his head were bloated and mottled – a corpse’s fists. Flushed and dazed, the

Senator looked around the room, blinking, slightly embarrassed – and, suddenly, exhausted. At some point he had stood up; now his legs gave way and he fell back into the armchair, raising a

puff of tobacco. On the rug, just out of reach, was the pipe he must have dropped, lying at one end of a spray of cooling ashes. He did not reach for it; he did not have the energy. With his

handkerchief he mopped at his spittle-laced chin.

The wizard regarded him, wrinkled fingers interlaced atop his staff.

“I don’t even know why I’m talking to you,” the Senator mumbled. He leaned forward, eyes closed, feeling queasy. “You make my head hurt.”

“Inhibiting spell,” the wizard said. “It prevented your throwing me out. Temporary, of course. One bumps against it, as against a low ceiling.”

“Leave me alone,” the Senator moaned.

“Such talents,” the wizard murmured. “Such energy, and for what?”

“At least I’m a halfling,” the Senator said.

“Largely, yes,” the wizard said. “Is genealogy one of your interests, Senator? We wizards have a knack for it. We can see bloodlines, just by looking. Do you really want to

know how…interesting…your bloodline is?”

The Senator mustered all his energy to shout, “Get out!” – but heard nothing. Wizardry kept the words in his mouth, unspoken.

“There are no evil races,” the wizard repeated, “however convenient the notion to patriots, and priests, and storytellers. You may summon your trolls now.” His gesture

was half shrug, half convulsion.

Suddenly the Senator had his voice back. “Boys!” he squawked. “Boys! Come quick! Help!” As he hollered, the wizard seemed to roll up like a windowshade, then become a

tubular swarm of fireflies. By the time the trolls knocked the door into flinders, most of the fireflies were gone. The last dying sparks winked out on their scaly shoulders as the trolls halted,

uncertain what to pulverize. The Senator could hear their lids scrape their eyeballs as they blinked once, twice. The troll on

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...