- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

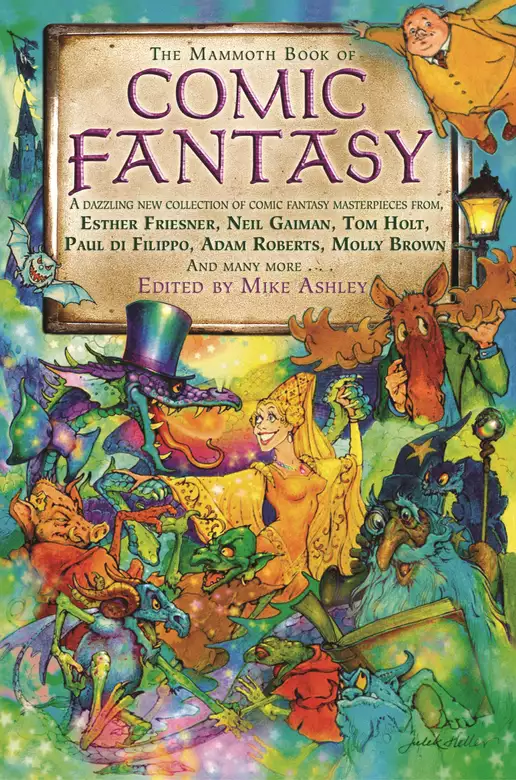

This dazzling new collection of off-the-wall fantasies features stories from the minds of the funniest writers in the field, including Esther Friesner, Neil Gaiman, Tom Holt, Paul di Filippo, Adam Roberts and Molly Brown. Here are 35 stories guaranteed to reassure us that the next-door world will be just as mad as this one.

It includes a mix of brand-new stories and rare finds or forgotten gems, with a wide range of tales to suit every taste in humour. From the missionary plunged into the bizarre initiation rituals of a lost tribe to the bloke who thought magic would help his love life, from a wizard allergic to magic who sneezes his way into chaos to a man who finds his shoes have taken over control of his life, The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy unfalteringly turns fantasy and horror fiction on its head and makes magic into mayhem. A welcome new shot of comic genius in the sphere of fantasy fiction.

Release date: April 10, 2014

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy

Mike Ashley

“The Warlock’s Daughter” © 1937 by Anthony Armstrong. First published in The Strand Magazine, January 1938. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“Fall’n Into the Sear” © 1998 by James Bibby. First printing, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“Press Ann” © 1991 by Terry Bisson. First published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, August 1991. Reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent.

“The Fifty-First Dragon” © 1921 by Heywood Broun. First published in Seeing Things at Night (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1921). Copyright expired in 1977.

“Ruella in Love” © 1993 by Molly Brown. First published in Interzone, October 1993. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Tender is the Night-Gaunt” © 1998 by Peter Cannon. First printing, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“The Glass Slip-Up” © 1998 by Louise Cooper. First printing, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of Wade and Doherty Literary Agency as agents for the author’s estate.

“Peregrine: Alflandia” © 1973 by Avram Davidson. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, August 1973, and subsequently incorporated in Peregrine: Secundus (New York: Berkley Books, 1981). Reprinted by permission of the Virginia Kidd Agency, Inc., on behalf of the author’s estate.

“Golden Apples of the Sun” © 1984 by Gardner Dozois, Jack Dann and Michael Swanwick. First published in a slightly shorter version as “Virgin Territory” in Penthouse, March 1984. This longer version first published in The Year’s Best Fantasy Stories: 11 edited by Art Saha (New York: DAW Books, 1985). Reprinted by permission of the Virginia Kidd Agency, Inc., on behalf of the authors.

“Wu-Ling’s Folly” © 1982 by Thranx, Inc. First published in Fantasy Book, August 1982. Reprinted by permission of the Virginia Kidd Agency, Inc., on behalf of the author.

“Death Swatch” © 1996 by Esther Friesner. First published in Castle Fantastic edited by John DeChancie and Martin H. Greenberg. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Shoggoth’s Old Peculiar” © 1998 by Neil Gaiman. First printing, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“A Malady of Magicks” © 1978 by Craig Shaw Gardner. First published in Fantastic Stories, October 1978. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“A Fortnight of Miracles” © 1964 by Randall Garrett. First published in Fantastic, Stories of the Imagination, February 1965. Reprinted by permission of the Tracy Blackstone Literary Agency on behalf of the author’s estate.

“The Cunning Plan” © 1998 by Anne Gay. First printing, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“The Return of Max Kearny” © 1981 by Ron Goulart. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, December 1981. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Pizza to Go” © 1998 by Tom Holt. First printing, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“The Toll Bridge” © 1988 by Harvey Jacobs. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, March 1988. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Cat With Two Tails” © 1992 by Terry Jones. First published in Fantastic Stories (London: Pavilion Books, 1992). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Been a Long, Long Time” © 1970, 1998 by R. A. Lafferty. First published in Fantastic Stories, December 1970. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“The Distressing Damsel” © 1984 by David Langford. First published in Amazing Stories, July 1984. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“War of the Doom Zombies” © 1971 by Richard A. Lupoff. First published in Fantastic Stories, June 1971. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Unpleasantness at the Baloney Club” © 1998 by F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre. First printing, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“Alaska” © 1989 by John Morressy. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, March 1989. Reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, the William Morris Agency.

“Aphrodite’s New Temple” © 1998 by Amy Myers. First printing, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Dorian Literary Agency.

“Troll Bridge” © 1992 by Terry Pratchett. First published in After the King edited by Martin H. Greenberg (New York: Tor Books, 1992). Reprinted by permission of the author’s agent, Colin Smythe, Ltd.

“The Boscombe Walters Story” © 1996 by Robert Rankin. First published in A Dog Called Demolition (London: Corgi Books, 1996). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Return of Mad Santa” © 1981 by Al Sarrantonio. First published in Fantasy Book, February 1982. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“An Eye for an Eye, a Tooth for a Tooth” © 1994 by Lawrence Schimel. First published in Young Blood edited by Mike Baker (New York: Zebra Books, 1994). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Queen of the Green Sun” © 1959 by Jack Sharkey. First published in Fantastic, May 1959. Reprinted by permission of Pat Sharkey and the agent for the author’s estate, Samuel French, Inc.

“Mebodes’ Fly” © 1992 by Harry Turtledove. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, July 1992. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Tale of the Seventeenth Eunuch” © 1992 by Jane Yolen. First published in Aladdin: Master of the Lamp, edited by Mike Resnick and Martin H. Greenberg (New York: DAW Books, 1992). Reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Curtis Brown, Ltd, New York.

Mike Ashley

INTRODUCTION THE FIRST – FOR THOSEWHO DON’T READ INTRODUCTIONS

INTRODUCTION THE SECOND – FOR THOSEEXPECTING A SILLY INTRODUCTION

No, I’m sorry. You’ve got the rest of the book to laugh at. You’re not laughing at my introduction as well. This is the one chance I get to say something, and I mean to say something sensible.

INTRODUCTION THE THIRD – FOR THOSEEXPECTING A PROPER INTRODUCTION

“Beauty,” they say, “is in the eye of the beholder.” That’s probably true about humour as well. Well, not in the eye, maybe in the ear . . . or is it the brain . . . ? Well, no matter, what one person finds funny, another may not.

So, I can’t guarantee that every story in this book will make you laugh, but I’d be very surprised if most of them don’t. I’ve cast my net far and wide (or should that be deep?) to bring together many of the best writers in the world of comic fantasy. There are the ones you’re bound to know – Terry Pratchett, Tom Holt, Robert Rankin, Terry Jones, Alan Dean Foster. And maybe the ones you’re just getting to know – James Bibby, Esther Friesner, Neil Gaiman, Craig Shaw Gardner. Then there are the ones you don’t want to know – um, no, we’ll leave them out of it.

There are certainly some you ought to know. I’ve been reading fantasy fiction for over thirty years, and there are many delightful stories tucked away in old books and magazines by writers who are not as well known as they should be. Some, like Anthony Armstrong, Avram Davidson, Jack Sharkey and Randall Garrett, are, alas, no longer with us, but we can still have the pleasure of reminding ourselves just what great writers they were. Others, like Harry Turtledove, John Morressy, Richard Lupoff, Harvey Jacobs and Ron Goulart, are, thankfully, still with us, and still producing excellent stories – and they should be better known, too.

I’ve coaxed a few writers to this book that you might not immediately associate with humorous fantasy. Amy Myers, for instance, the renowned writer of Victorian/Edwardian mystery novels, has an irrepressible sense of humour which jumped at the opportunity to express itself. Louise Cooper is best known for her sinister occult fantasies, and doesn’t get much chance to trip the light fantastic. Terry Bisson is the award-winning author of several off-beat stories, some of which are darkly comic.

I hope I’ve included something for everyone. About half the stories are set entirely in fantasy lands and half set in an almost recognizable here and now (or there and then in some cases), so I’ve alternated the settings more or less with each story.

If you like your stories in the style of Terry Pratchett, then you also want to try the stories by Avram Davidson, Craig Shaw Gardner, Esther Friesner, John Morressy, James Bibby and Molly Brown. If you like your humour a little on the dark side, then check out the stories by Lawrence Schimel, Jane Yolen, Al Sarrantonio and Harvey Jacobs. If you go for the off-beat story, then try the ones by Terry Bisson, Anne Gay, Tom Holt, Harvey Jacobs, R.A. Lafferty and, for that matter, Edward Lear. If you’re into spoofs, then check out Anthony Armstrong, Louise Cooper, David Langford and Peter Cannon. Or, if you just like to laugh at the world about you, then try Neil Gaiman, Robert Rankin, F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre or Al Sarrantonio.

I hope most of the stories will make you laugh out loud. Others will make you smile. All, I’m sure, will entertain.

Okay, even a proper introduction has to end, and I’m sure you’re all the better for reading it. Now you can join the others in the rest of the book. They won’t be that far ahead of you.

Mike Ashley

Avram Davidson

Avram Davidson (1923–93) was one of the great treasures of fantasy and science fiction. He was critically acclaimed, winning all kinds of awards, and for forty years produced his own style of idiosyncratic stories which earned him a vociferous cult following. There is a profusion of material I could have drawn upon. I was originally tempted to use one of his bizarre stories featuring Doctor Eszterhazy, set in an alternate world just prior to World War I. A number of these will be found in The Enquiries of Doctor Eszterhazy (1975). In the end, though, I found myself irrestistibly drawn to this opening sequence from Peregrine: Secundus (1981), which Davidson wrote originally as a separate story. This was a sequel to Peregrine: Primus (1971), set in the last days of the Roman Empire. It might be history, but not as we know it.

The King of the Alves was taking his evening rest and leisure after a typical hard day’s work ferreting in the woods behind the donjeon-keep, which – in Alfland – was a goodish distance from the Big House. It was usual, of course, for the donjeon-keep to be kept as part and parcel of the Big House, but the Queen of Alfland had objected to the smell.

“It’s them drains, me dear,” her lord had pointed out to her more than once when she made these objections. “The High King isn’t due to make a Visitation this way for another half-a-luster, as well you know. And also as well you know what’d likely happen to me if I was to infringe upon the High Royal Monopoly and do my own plumbing on them drains, a mere pettiking like me.”

“I’d drains him, if I was a man,” said the Queen of Alfland.

“And the prices as he charges, too! ’Tisn’t as if he was contented with three peppercorns and a stewed owl in a silver tassy, like his father before him; ah! there was a High King for you! Well, well, I see it can’t be helped, having wedded a mouse instead of a proper man; well, then move the wretched donjeon-keep, it doesn’t pay for itself no-how, and if it wasn’t as our position requires we have one, blessed if I’d put up with it.”

So the donjeon-keep had been laboriously taken down and laboriously removed and laboriously set up again just this side of the woods; and there, of a very late afternoon, the King of the Alves sat on a hummock with his guest, the King of Bertland. Several long grey ears protruded from a sack at their feet, and now and then a red-eyed ferret poked his snouzel out of a royal pocket and was gently poked back in. The Master of the Buckhounds sat a short ways aways, a teen-age boy who was picking the remnants of a scab off one leg and meditatively crunching the pieces between his teeth. He was Alfland’s son and heir; there were of course not really any buckhounds.

“Well, Alf, you hasn’t done too bad today,” the royal guest observed after a while.

“No, I hasn’t, Bert, and that’s a fact. Stew for the morrow, and one day at a time is all any man dare look for to attend to and haccomplish, way I look at it.” The day was getting set to depart in a sort of silver-gilt haze, throstles were singing twit-twit-thrush, and swallows were flitting back and forth pretending they were bats. The Master of the Buckhounds arose.

“Hey, Da, is they any bread and cheese more?” he asked.

“No, they isn’t, Buck. Happen thee’ll get they dinner soon enough.”

The Master of the Buckhounds said that he was going to see could he find some berries or a musk-room and sauntered off into the thicket. His sire nudged the guest. “Gone to play with himself, I’ll be bound,” said he.

“Why don’t ’ee marry ’im off?” asked the King of Bertland, promptly. “There’s our Rose, has her hope chest all filled and still as chaste as the day the wise woman slapped her newborn bottom, ten year ago last Saturnalia, eh?”

The King of the Alves grunted moodily. “Hasn’t I sudggestered this to his dam?” he asked, rhetorically. “ ‘Here’s Bert come for to marry off his datter,’ says I, ‘for thee doesn’t think there’s such a shortage o’ rabbiting in Bertland he have to come here for it, whatever the formalities of it may be. And Princess Rose be of full age and can give thee a hand in the kitching,’ says I. But, no, says she. For why? Buck haven’t gone on no quest nor haven’t served no squire time at the High King’s court and ten-year-old is too old-fashioned young and he be but a boy hisself and she don’t need no hand in the kitching and if I doesn’t like the way me victuals be served, well, I can go and eat beans with the thralls, says she.

“—Well, do she natter that Buck have pimples, twill serve she right, say I. Best be getten back. Ar, these damp edgerows will give me the rheum in me ips, so we sit ere more, eh?”

He hefted his sack of hares and they started back. The King of Bertland gestured to the donjeon-keep, where a thin smoke indicated the warder was cooking his evening gruel. “As yer ransomed off King Baldwin’s heir as got tooken in the humane man-trap last winter what time e sought to unt the tusky boar?”

The walls of Alftown came into sight, with the same three breeches and a rent which characterized the walls of every castle and capital town as insisted on by Wilfredoric Conqueror, the late great-uncle of the last High King but one. Since that time, Alfish (or Alvish, as some had it) royalty had been a-dwelling in a Big House, which was contained behind a stout stockade: this, too, was customary.

“What, didn’t I notify you about that, Bert?” the Alf-king asked, with a slightly elaborate air of surprise. “Ah, many’s the good joke and jest we’ve had about that in the fambly, ‘Da has tooken King Baldy’s hair, harharharhar!’ Yus, the old man finally paid up, three mimworms and a dragon’s egg. ‘Mustn’t call him King Baldy now he’s got his heir back, horhorhorhor!’ Ah, what’s life wiffart larfter? Or, looking hat it another way, wiffart hhonor: we was meaning to surprise you, Bert, afore you left, by putten them mimworms and that dragon’s hegg hinto a suitable container wif a nice red ribbon and say, ‘Ere you be, King o’ Bertland, hand be pleased to haccept this as your winnings for that time we played forfeits last time we played it.’ Surprise yer, yer see. But now yer’ve spoiled that helement of it; ah, well, must take the bitter wiv the sweet.”

That night after dinner the three mimworms and the dragon’s egg were lifted out from the royal hidey-hole and displayed for the last time at Alf High-Table before being taken off to their new home. Princess Pearl and Princess Ruby gave over their broidered-work, and young Buck (he was officially Prince Rufus but was never so-called) stopped feeding scruffles to his bird and dog – a rather mangy-looking mongrel with clipped claws – and Queen Clara came back out of the kitchen.

“Well, this is my last chance, I expect,” said Princess Pearl, a stout good-humored young girl, with rather large feet. “Da, give us they ring.”

“Ar, this time, our Pearl, happen thee’ll have luck,” her sire said, indulgently; and he took off his finger the Great Sigil-Stone Signet-Ring of the Realm, which he occasionally affixed to dog licenses and the minutes of the local wardmotes, and handed it to her. Whilest the elders chuckled indulgently and her brother snorted and her baby sister looked on with considerable envy, the elder princess began to make the first mystic sign – and then, breaking off, said, “Well, now, and since it is the last chance, do thee do it for me, our Ruby, as I’ve ad no luck a-doin it for meself so far—”

Princess Ruby clapped her hands. “Oh, may I do it, oh, please, please, our Pearl? Oh, you are good to me! Ta ever so!” and she began the ancient game with her cheeks glowing with delight and expectation:

Mimworm dim, mimworm bright,

Make the wish I wish tonight:

By dragon egg and royal king,

Send now for spouse the son of a king!

The childish voice and gruff chuckles were suddenly all drowned out by screams, shouts, cries of astonishment, and young Buck’s anguished wail; for where his bird had been, safely jessed, there suddenly appeared a young man as naked as the day of his birth.

Fortunately the table had already been cleared, and, nakedness not ever having been as fashionable in East Brythonia (the largest island in the Black Sea) as it had been in parts farther south and west, the young man was soon rendered as decent as the second-best tablecloth could make him.

“Our Pearl’s husband! Our Pearl’s husband! See, I did do it right, look! Our Mum and our Da, look!” and Princess Ruby clapped her hands together. King Alf and King Bert sat staring and muttering . . . perhaps charms, or countercharms . . . Buck, with tears in his eyes, demanded his bird back, but without much in his tone to indicate that he held high hopes . . . Princess Pearl had turned and remained a bright, bright red . . . and Queen Clara stood with her hands on her hips and her lips pressed together and a face – as her younger daughter put it later: “O Lor! Wasn’t Mum’s face a study!”

Study or no, Queen Clara said now, “Well, and pleased to meet this young man, I’m sure, but it seems to me there’s more to this than meets the heye. Our Pearl is still young for all she’s growed hup into a fine young ’oman, and I don’t know as I’m all that keen on her marrying someone as we knows nuffink abahrt, hexcept that he use ter be a bird; look at that there Ellen of Troy whose dad was a swan, Leda was er mum’s name; what sort of ome life d’you think she could of ad, no better than they should be the two of them, mother and daughter – what! Alfland! Yer as some’at to say, as yer!” she turned fiercely on her king, who had indeed been mumbling something about live and let live, and it takes all kinds, and seems a gormly young man; “Ah, and if another Trojan War is ter start, needn’t think to take Buck halong and—”

But she had gone too far.

“Nah then, nah then, Queen Clara,” said her king. “Seems to me yer’ve gotten things fair muddled, that ’ere Trojing War come abaht acause the lady herself ad more nor one usband, an’ our Pearl asn’t – leastways not as I knows of. First yer didn’t want Buck to get married, nah yer wants our Pearl ter stay at ome. I dessay, when it come our Ruby’s time, yer’ll ave some’at to say bout that, too. Jer want me line, the royal line-age o’ the Kings of Alfland, as as come down from King Deucalion’s days, ter die aht haltergether?” And to this the queen had no word to utter, or, at least, none she thought it prudent to; so her husband turned to the young man clad in the second-best tablecloth (the best, of course, always being saved for the lustral Visitations of the High King himself) – and rather well did he look in it, too – and said, “Sir, we bids yer welcome to this ere Igh Table, which it’s mine, King Earwig of Alfland is me style and title, not but what I mightn’t ave another, nottersay other ones, if so be I ad me entitles and me right. Ah, ad not the King o’ the Norf, Arald Ardnose, slain Earl Oscaric the Ostrogoth at Slowstings, thus allowing Juke Wilfred of Southmandy to hobtain more than a mere foot’old, as yer might call it, this ud be a united kingdom today instead of a mere patch’ork quilt of petty kingdomses. Give us an account of yerself, young man, as yer hobliged to do hanyway according to the lore.”

And at once proceeded to spoil the effect of this strict summons by saying to his royal guest, “Pour us a drain o’ malt and one for his young sprig, wonthcher, Bert,” and handed the mug to the young sprig with his own hands and the words, “Ere’s what made the deacon dance, so send it down the red road, brother, and settle the dust.”

They watched the ale go rippling down the newcomer’s throat, watched him smack his lips. Red glows danced upon the fire-pit hearth, now and then illuminating the path of the black smoke all the way up to the pitchy rafters where generations of other smokes had left their soots and stains. And then, just as they were wondering whether the young man had a tongue or whether he peradventure spoke another than the one in which he had been addressed, he opened his comely red lips and spoke.

“Your Royal Grace and Highnesses,” he said, “and Prince and Princesses, greetings.”

“Greetings,” they all said, in unison, including, to her own pleased surprise, Queen Clara, who even removed her hands from under the apron embroidered with the golden crowns, where she had been clasping them tightly, and sat down, saying that the young man spoke real well and was easily seen to have been well brought hup, whatsoever e ad been a bird: but there, we can’t always elp what do befall us in this vale of tears.

“To give an account of myself,” the young man went on, after no more than a slight pause, “would be well lengthy, if complete. Perhaps it might suffice for now for me to say that as I was on the road running north and east out of Chiringirium in the Middle, or Central, Roman Empire, I was by means of a spell cast by a benevolent sorcerer, transformed into a falcon in order that I might be saved from a much worse fate; that wilst in the form of that same bird I was taken in a snare and manned by one trained in that art, by him sold or exchanged for three whippets and a brace of woodcock to a trader out of Tartary by way of the Crimea; and by him disposed of to a wandering merchant, who in turn made me over to this young prince here for two silver pennies and a great piece of gammon. I must say that this is very good ale,” he said, enthusiastically. “The Romans don’t make good ale, you know, it’s all wine with them. My old dadda used to tell me, ‘Perry, my boy, clean barrels and good malt make clean good ale . . .’ ”

And, as he recalled the very tone of his father’s voice and the very smell of his favorite old cloak, and realized that he would never see him more, a single tear rolled unbidden from the young man’s eye and down the down of his cheek and was lost in the tangle of his soft young beard, though not lost to the observation of all present. Buck snuffled, Ruby climbed up in the young man’s lap and placed her slender arms round his neck, Queen Clara blew her nose into her gold-embroidered apron, King Bert cleared his throat, and King Alf-Earwig brushed his own eyes with his sleeve.

“Your da told yer that, eh?” he said, after a moment. “Well, he told yer right and true— What, call him dadda, do ’ee? Why, yer must be one a them Lower Europeans, then, for I’ve eard it’s their way o’ speech. What’s is name, then – and what’s yours, for that matter?”

Princess Pearl, speaking for the first time since giving the ring to her small sister, said, “Why, Da, haven’t he told us that? His name is Perry.” And then she blushed an even brighter red than ever.

“Ah, he have, our Pearl. I’ll be forgetting my own name next. Changed into a falcon-bird and then changed back again, eh? Mind them mimworms and that ’ere dragon hegg, Bert; keep em safe locked hup, for where there be magic there be mischief—But what’s yer guvnor’s name, young Perry?”

Young Perry had had time to think. Princess Pearl was to all appearances an honest young woman and no doubt skilled in the art of spindle and distaff and broider-sticking, as befitted the daughter of a petty king; and as befitted one, she was passing eager and ready for marriage to the son of another such. But Perry had no present mind to be that son. Elliptically he answered with another question. “Have you heard of Sapodilla?”

Brows were knit, heads were scratched. Elliptics is a game at which more than one can play. “That be where you’re from, then?” replied King Alf.

The answer, such as it was, was reassuring. He felt he might safely reveal a bit more without revealing too much more. “My full name, then, is Peregrine the son of Paladrine, and I am from Sapodilla and it is in Lower Europe. And my father sent me to find my older brother, Austin, who looks like me, but blond.”— This was stretching the truth but little. Eagerness rising in him at the thought, he asked, “Have any of you seen such a man?”

King Bert took the answer upon himself. “Mayhap such a bird is what ee should better be a-hasking for, horhorhor!” he said. And then an enormous yawn lifted his equally enormous mustache.

Someone poked Perry in the side with a sharp stick. He did not exactly open his eyes and sit up, there on the heap of sheepskin and blanketure nigh the still hot heap of coals in the great hall; for somehow he knew that he was sleeping. This is often the prelude to awakening, but neither did he awake. He continued to lie there and to sleep, though aware of the poke and faintly wondering about it. And then it came again, and a bit more peremptory, and so he turned his mind’s eye to it, and before his mind’s eye he saw the form and figure of a man with a rather sharp face, and this one said to him, “Now, attend, and don’t slumber off again, or I’ll fetch you back, and perhaps a trifle less pleasantly; you are new to this island, and none come here new without my knowing it, and yet I did not know it. Attend, therefore, and explain.”

And Peregrine heard himself saying, in a voice rather like the buzzing of bees (and he complimented himself, in his dream, for speaking thus, for it seemed to him at that time and in that state that this was the appropriate way for him to be speaking). “Well, and well do I now know that I have passed through either the Gate of Horn or the Gate of Ivory, but which one I know not, do you see?”

“None of that, now, that is not my concern: explain, explain, explain; what do you here and how came you here, to this place, called ‘the largest island in the Black Sea’, though not truly an island . . . and, for that matter, perhaps not even truly in the Black Sea . . . Explain. Last summons.”

Perry sensed that no more prevarications were in order. “I came here, then, sir, in the form of an hawk or falcon, to which state I was reduced by white witchery; and by white witchery was I restored to own my natural manhood after arriving.”

The sharp eyes scanned him. The sharp mouth pursed itself in more than mere words. “Well explained, and honestly. So. I have more to do, and many cares, and I think you need not be one of them. For now I shall leave you, but know that from time to time I shall check and attend to your presence and your movements and your doings. Sleep!”

Again the stick touched him, but now it was more like a caress, and the rough, stiff fleece and harsh blankets felt as smooth to his naked skin as silks and downs.

He awoke again, and properly this time, to see the grey dawnlight touched with pink. A thrall was blowing lustily upon the ember with a hollowed tube of wood and laying fresh fagots of wood upon it. An even lustier rumble of snores came from the adjacent heap of covers, whence protruded a pair of hairy feet belonging, presumably, to the King of Bertland. And crouching by his own side was Buck.

Who said, “Hi.”

“Hi,” said Perry, sitting up.

“You used to be a peregrine falcon and now you’re a peregrine man?” the younger boy asked.

“Yes. But don’t forget that I was a peregrine man before becoming a falcon. And let me thank you for the care and affection which you gave me when I was your hawk, Buck. I will try to replace myself . . . or replace the bird you’ve lost, but as I don’t know just when I can or how, even, best I make no promise.”

At this point the day got officially underway at Alfland Big House, and there entered the king himself, followed by the Lord High Great Steward, aged eight (who, having ignominiously fail

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...