- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

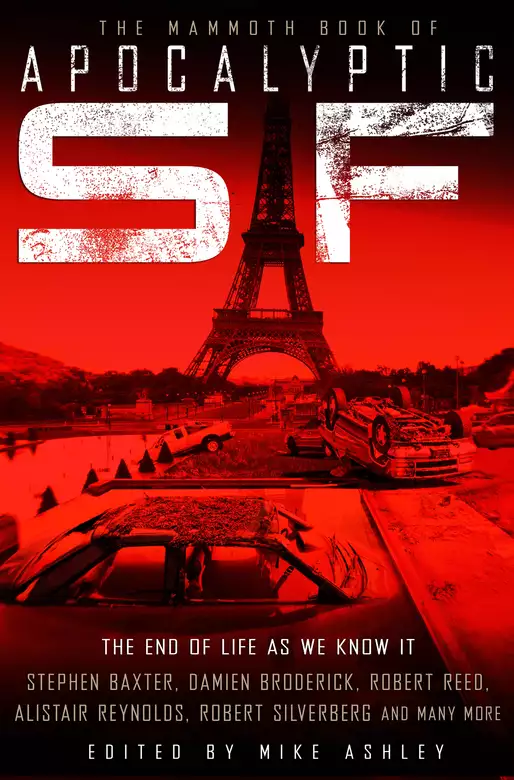

The last sixty years have been full of stories of one or other possible Armageddon, whether by nuclear war, plague, cosmic catastrophe or, more recently, global warming, terrorism, genetic engineering, AIDS and other pandemics. These stories, both pre- and post-apocalyptic, describe the fall of civilization, the destruction of the entire Earth, or the end of the Universe itself. Many of the stories reflect on humankind's infinite capacity for self-destruction, but the stories are by no means all downbeat or depressing - one key theme explores what the aftermath of a cataclysm might be and how humans strive to survive.

Release date: May 27, 2010

Publisher: Robinson

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Apocalyptic SF

Mike Ashley

The Mammoth Book of Extreme Science Fiction, The Mammoth Book of Extreme Fantasy, The Mammoth Book of Perfect Crimes and Impossible Mysteries and The Mammoth Book of

Mindblowing SF. He has also written the biography of Algernon Blackwood, Starlight Man, and a comprehensive study, The Mammoth Book of King Arthur. He lives in Kent with his wife

and three cats and when he gets the time he likes to go for long walks.

Also available

The Mammoth Book of 20th Century Science Fiction

The Mammoth Book of Best Crime Comics

The Mammoth Book of Best Horror Comics

The Mammoth Book of Best New Erotica 9

The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror 19

The Mammoth Book of Best New Manga 3

The Mammoth Book of Best New SF 21

The Mammoth Book of Best of Best New SF

The Mammoth Book of Best War Comics

The Mammoth Book of Bikers

The Mammoth Book of Boys’ Own Stuff

The Mammoth Book of Brain Workouts

The Mammoth Book of Celebrity Murders

The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Comic Quotes

The Mammoth Book of Cover-Ups

The Mammoth Book of CSI

The Mammoth Book of the Deep

The Mammoth Book of Dickensian Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Dirty, Sick, X-Rated & Politically Incorrect Jokes

The Mammoth Book of Egyptian Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Erotic Confessions

The Mammoth Book of Erotic Online Diaries

The Mammoth Book of Erotic Women

The Mammoth Book of Extreme Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Funniest Cartoons of All Time

The Mammoth Book of Hard Men

The Mammoth Book of Historical Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Illustrated True Crime

The Mammoth Book of Inside the Elite Forces

The Mammoth Book of International Erotica

The Mammoth Book of Jack the Ripper

The Mammoth Book of Jacobean Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of the Kama Sutra

The Mammoth Book of Killers at Large

The Mammoth Book of King Arthur

The Mammoth Book of Lesbian Erotica

The Mammoth Book of Limericks

The Mammoth Book of Maneaters

The Mammoth Book of Mindblowing SF

The Mammoth Book of Modern Battles

The Mammoth Book of Modern Ghost Stories

The Mammoth Book of Monsters

The Mammoth Book of Mountain Disasters

The Mammoth Book of New Gay Erotica

The Mammoth Book of New Terror

The Mammoth Book of On the Edge

The Mammoth Book of On the Road

The Mammoth Book of Paranormal Romance

The Mammoth Book of Pirates

The Mammoth Book of Poker

The Mammoth Book of Prophecies

The Mammoth Book of Roaring Twenties Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Sex, Drugs and Rock ’N’ Roll

The Mammoth Book of Short SF Novels

The Mammoth Book of Short Spy Novels

The Mammoth Book of Sorcerers’ Tales

The Mammoth Book of True Crime

The Mammoth Book of True Hauntings

The Mammoth Book of True War Stories

The Mammoth Book of Unsolved Crimes

The Mammoth Book of Vampire Romance

The Mammoth Book of Vintage Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Women Who Kill

The Mammoth Book of Zombie Comics

Edited and with an Introduction by

Mike Ashley

COPYRIGHT

Published by Robinson

ISBN: 978-1-8490-1495-3

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © Mike Ashley, 2010 (unless otherwise indicated)

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Robinson

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DZ

www.littlebrown.co.uk www.hachette.co.uk

The End of All Things • Mike Ashley

THE NATURE OF THE CATASTROPHE

When We Went to See the End of the World • Robert Silverberg

The End Of The World • Sushma Joshi

The Clockwork Atom Bomb • Dominic Green

Bloodletting • Kate Wilhelm

The Rain at the End of the World • Dale Bailey

The Flood • Linda Nagata

The End of the World Show • David Barnett

Fermi and Frost • Frederik Pohl

Sleepover • Alastair Reynolds

The Last Sunset • Geoffrey A. Landis

BEYOND ARMAGEDDON

Moments of Inertia • William Barton

The Books • Kage Baker

Pallbearer • Robert Reed

And the Deep Blue Sea • Elizabeth Bear

The Meek • Damien Broderick

The Man Who Walked Home • James Tiptree, Jr

A Pail of Air • Fritz Leiber

Guardians of the Phoenix • Eric Brown

Life in the Anthropocene • Paul Di Filippo

Terraforming Terra • Jack Williamson

THE END OF ALL THINGS

World Without End • F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre

The Children of Time • Stephen Baxter

The Star Called Wormwood • Elizabeth Counihan

All of the stories are copyright in the name of the individual authors or their estates as follows, and may not be reproduced without permission.

“The Rain at the End of the World” © 1999 by Dale Bailey. First published in Fantasy & Science Fiction, July 1999. Reprinted by permission of the

author.

“The Books” © 2010 by Kage Baker. First publication original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Linn Prentis

Agency.

“The End of the World Show” © 2006 by David Barnett. First published in Postscripts #9, Winter 2006. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Moments of Inertia” © 2004 by William Barton. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, April/May 2004. Reprinted by permission of

the author.

“The Children of Time” © 2005 by Stephen Baxter. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, July 2005. Reprinted by permission of the

author.

“And the Deep Blue Sea” © 2005 by Elizabeth Bear. First published on Sci Fiction, May 2005. Reprinted by permission of Don Congdon Associates, Inc. on

behalf of the author.

“The Meek” © 2004 by Damien Broderick. First published in Synergy SF edited by George Zebrowski (Waterville: Five Star, 2004). Reprinted by permission

of the author.

“Guardians of the Phoenix” © 2010 by Eric Brown. First publication original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“A Star Called Wormwood” © 2004 by Elizabeth Counihan. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, December 2004. Reprinted by

permission of the author.

“Life in the Anthropocene” © 2010 by Paul Di Filippo. First publication original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“When Sysadmins Ruled the World” © 2006 by CorDocCo, Ltd (UK). First published in Jim Baen’s Universe, August 2006. Reprinted by permission of the

author. Some rights reserved under a Creative Commons Attribution – ShareAlike – NonCommercial 3.0 license.

“The Clockwork Atom Bomb” © 2005 by Dominic Green. First published in Interzone #198, May/June 2005. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The End of the World” © 2002 by Sushma Joshi. First published on the Internet at http://www.eastoftheweb.com.

Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Last Sunset” © 1996 by Geoffrey A. Landis. First published in Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, February 1996. Reprinted by permission of

the author.

“A Pail of Air” © 1951 by Fritz Leiber. First published in Galaxy Science Fiction, December 1951. Reprinted by permission of Richard Curtis Associates

as agents for the author’s estate.

“World Without End” © 2010 by F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre. First publication original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“The Flood” © 1998 by Linda Nagata. First published in More Amazing Stories edited by Kim Mohan (New York: Tor, 1998). Reprinted by permission of the

author.

“Fermi and Frost” © 1985 by Frederik Pohl. First published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, January 1985. Reprinted by permission of

the author.

“Pallbearer” © 2010 by Robert Reed. First publication original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“Sleepover” © 2010 by Alastair Reynolds. First publication original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author.

“When We Went to See the End of the World” by Robert Silverberg © 1972 by Agberg Ltd. First published in Universe 2 edited by Terry Carr (New York: Ace

Books, 1972). Reprinted by permission of the author and Agberg Ltd.

“The Man Who Walked Home” © 1972 by Alice Sheldon. First published in Amazing Science Fiction Stories, May 1972. Reprinted by permission of the Virginia

Kidd Literary Agency as agent for the author’s estate.

“Bloodletting” © 1994 by Kate Wilhelm. First published in Omni, June 1994. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Terraforming Terra” © 1998 by Jack Williamson. First published in Science Fiction Age, November 1998, and incorporated into Terraforming Earth

(New York: Tor, 2001). Reprinted by permission of the Spectrum Literary Agency as agent for the author’s estate.

Mike Ashley

We seem to have a fascination for the Apocalypse, the end of all things. It’s not that we welcome it, least I hope not, but it seems that we can’t help wondering about

it, even predicting it. “The End is Nigh”, a phrase perhaps too-oft used to have the impact it once had, has now passed into our language to signify yet another fallacious

prediction.

There are the obvious religious connotations of the Apocalypse or the Day of Judgment – the biblical Armageddon, the Nordic Ragnarök, the Islamic Qiyamah (Doomsday), and so on –

and this in turn may feed into the growing scientific awareness of our mortality through such possibilities as pandemics, cosmic catastrophes, climate change or the inevitable death of the Sun. The

imagery of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, representing Conquest, War, Famine and Death, is as potent today as ever.

This anthology brings together stories that look at many of the ways that the Earth, or life upon it, may be destroyed, from plagues to floods, nuclear war to collision with a comet, alien

invasion to new technologies run wild, and a few things beyond your wildest imaginings.

It’s all here, and more besides. But I didn’t want an anthology where every story ended with death and destruction – that would become rather depressing over 500 pages –

so to provide a balance I decided to introduce some hope for the future. At least half the stories take us beyond the end of civilization, even the end of the Earth, and look at how life –

albeit not as we know it – may go on. Science fiction has had its own fascination with the end of all things since at least Le Dernier Homme (“The Last Man”) written by the

French priest Jean-Baptiste Cousin de Grainville at the end of the eighteenth century. He had lived through the French Revolution, which had rather soured his view of the world and drove him into

depression and eventual suicide in 1805, leaving this pioneering work in manuscript. It has some remarkably advanced ideas in depicting a world which, through mismanagement and overpopulation, had

become ecologically exhausted.

The experience of the Reign of Terror doubtless fuelled de Grainville’s work, and it is not surprising that certain events, such as the end of a century (or millennium) or World Wars,

focus minds on a potential Apocalypse. Although a few books followed de Grainville’s – including the like-named The Last Man (1826) by Mary Shelley, the author of

Frankenstein, which had humanity wiped out by a virulent plague, and Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion” (1839), one of the first stories to have

Earth destroyed by a comet – the real torrent of books came towards the end of the nineteenth century.

Two novels served as precursors to the main event: After London (1885) by Richard Jefferies, depicted a Britain that has reverted to the Stone Age following an unspecified catastrophe;

The Last American (1889) by John Ames Mitchell has a Persian expedition explore the ruins of New York, the United States having been destroyed by social unrest.

The noted French astronomer, Camille Flammarion, wrote one of the first major novels of worldwide disaster, La fin du monde (1894), better known as Omega: The Last Days of the

World, where a vast comet not only destroys life on Earth but also on Mars. H.G. Wells almost destroyed all life in “The Star” (1897) but salvation was at hand thanks to the Moon.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, best known for creating Sherlock Holmes, combined the ideas of a plague and cosmic disaster in The Poison Belt (1913), where he has the Earth pass through a toxic

belt in space. M.P. Shiel had used a similar idea in The Purple Cloud (1901), when a volcano releases a mass of poisonous vapour from deep within the Earth. Wells developed another form of

Armageddon when human life is threatened by the arrival of the Martians in The War of the Worlds (1898).

There were the inevitable apocalyptic stories following the First World War. Edward Shanks saw the end of civilization in The People of the Ruins (1920), while in Nordenholt’s

Million (1923) J.J. Connington showed how science might bring civilization back from the brink of an ecological disaster. Interestingly, one of the earliest stories to consider how civilization

might crumble through an over-reliance on technology was written as far back as 1909 by E.M. Forster in “The Machine Stops”.

The Second World War and the detonation of the A-bomb inevitably brought forth many stories of a nuclear holocaust such as The Long Loud Silence (1952) by Wilson Tucker, On the

Beach (1957) by Nevil Shute and, perhaps the best known, Dr Strangelove (1963), the Stanley Kubrick film based on the novel Red Alert by Peter George. The Cold War saw a rise in

disaster novels generally, particularly in Britain, where The Day of the Triffids (1951) by John Wyndham, The Death of Grass (1956) by John Christopher, White August (1955) by

John Boland and The Tide Went Out (1958) by Charles Eric Maine created what veteran British SF author Brian Aldiss later termed the “cosy catastrophe”. J. G. Ballard established

his reputation with a quartet of disaster novels based on the four elements of air, water, fire and earth: The Wind From Nowhere (1961), The Drowned World (1962), The Burning

World (1964) and The Crystal World (1966).

The welter of catastrophe novels and films grew exponentially with the approach of the millennium. Life on Earth is all but wiped out by a comet in Lucifer’s Hammer (1977) by Jerry

Pournelle and Larry Niven. We see how isolated survivors cope in a post-holocaust world in The Postman (1985) by David Brin and in The Gate to Women’s Country (1988) by Sheri S.

Tepper. Sea levels rise in The Road to Corlay (1978) by Richard Cowper and the United States is flooded in Forty Signs of Rain (2004) by Kim Stanley Robinson, while Stephen Baxter

drowns the Earth in Flood (2008). Greg Bear has aliens systematically destroying the solar system in The Forge of God (1987). In The Stand (1978), a genuinely apocalyptic

novel, Stephen King has most of humanity wiped out by a virulent flu strain, whilst a man-made plague destroys civilization in David Palmer’s Emergence (1984). There’s a combined

nuclear and ecological holocaust in Mother of Storms (1994) by John Barnes, while a major cosmic catastrophe causes climate change in Charles Sheffield’s Aftermath (1998). Most

recently Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006), which won a Pulitzer Prize, presents a very bleak vision of a world all but destroyed by some unexplained catastrophe. Recent TV series such

as Survivors, Deepwater Black and Jericho and films such as Deep Impact, the Terminator series and Armageddon continue to stimulate our thoughts and fill

our minds with apocalyptic imagery.

All of which goes to show the popularity and enormity of the field and the richness of its history, and created something of a challenge in assembling this anthology. I had considered including

many of the classics of the genre but found there was so much new fiction being produced in the last ten years or so that I only had room to squeeze in a couple of older stories, those by Fritz

Leiber and Robert Silverberg.

What was so noticeable about the new strain of apocalyptic fiction was how much it showed our fear of new technology, particularly nanotechnology. I could have filled this book with stories of

nanotechdoom alone but I wanted to get a good spread of catastrophes, both pre- and post-apocalyptic and the inevitable dying Earth. You will find plagues or the threat of plagues in the stories by

Robert Reed and Kate Wilhelm; floods in those by Dale Bailey and Linda Nagata; a nuclear holocaust and its aftermath in those by Frederik Pohl and Elizabeth Bear; climate change in the stories by

Eric Brown and Paul Di Filippo; cosmic disasters in those by David Barnett, Geoffrey Landis and William Barton, and the threat of technology or how it might save us in the stories by Damien Broderick and F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre. Alastair Reynolds brings an entirely new form of apocalypse in his novelette, one of six new stories in this anthology. We travel into the far distant

future to see how humanity re-evolves in Jack Williamson’s story, and the end of the human race in the stories by Stephen Baxter and Elizabeth Counihan.

But as I predicted, it is not all doom and gloom. Many of the stories show the resilience of mankind in coping with disaster and rebuilding the world. These may be warning stories but there are

also messages of hope here.

The Beginning is Nigh …

Robert Silverberg

We start on a fairly light-hearted note with this parody of the end-of-the-world theme where time travel allows people to witness the final apocalypse. But which

one?

Created a Grand Master by the Science Fiction Writers of America in 2004, Robert Silverberg is the dean of science fiction, having been writing prolifically for over fifty years,

producing not only an immense body of work but one of remarkable quality and diversity. Amongst his major works are Nightwings (1969), A Time of Changes (1971), Dying Inside

(1972), Born With the Dead (1974)¸ The Stochastic Man (1975), Lord Valentine’s Castle (1980) and The Secret Sharer (1989). Silverberg has written his

own share of apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic works. To Open the Sky (1967) is set in a claustrophobically overpopulated future, whilst At Winter’s End (1988) sees how

humanity recovers after a new Ice Age.

NICK AND JANE were glad that they had gone to see the end of the world, because it gave them

something special to talk about at Mike and Ruby’s party. One always likes to come to a party armed with a little conversation. Mike and Ruby give marvelous parties.

Their home is superb, one of the finest in the neighborhood. It is truly a home for all seasons, all moods. Their very special corner of the world. With more space indoors and out … more

wide-open freedom. The living room with its exposed ceiling beams is a natural focal point for entertaining. Custom-finished, with a conversation pit and fireplace. There’s also a family room

with beamed ceiling and wood paneling … plus a study. And a magnificent master suite with a twelve-foot dressing room and private bath. Solidly impressive exterior design. Sheltered

courtyard. Beautifully wooded one-third of an acre grounds. Their parties are highlights of any month. Nick and Jane waited until they thought enough people had arrived. Then Jane nudged Nick and

Nick said gaily, “You know what we did last week? Hey, we went to see the end of the world!”

“The end of the world?” Henry asked.

“You went to see it?” said Henry’s wife Cynthia.

“How did you manage that?” Paula wanted to know.

“It’s been available since March,” Stan told her. “I think a division of American Express runs it.”

Nick was put out to discover that Stan already knew. Quickly, before Stan could say anything more, Nick said, “Yes, it’s just started. Our travel agent found out for us. What they do

is they put you in this machine, it looks like a tiny teeny submarine, you know, with dials and levers up front behind a plastic wall to keep you from touching anything, and they send you into the

future. You can charge it with any of the regular credit cards.”

“It must be very expensive,” Marcia said.

“They’re bringing the costs down rapidly,” Jane said. “Last year only millionaires could afford it. Really, haven’t you heard about it before?”

“What did you see?” Henry asked.

“For a while, just greyness outside the porthole,” said Nick. “And a kind of flickering effect.” Everybody was looking at him. He enjoyed the attention. Jane wore a rapt,

loving expression. “Then the haze cleared and a voice said over a loudspeaker that we had now reached the very end of time, when life had become impossible on Earth. Of course, we were sealed

into the submarine thing. Only looking out. On this beach, this empty beach. The water a funny grey color with a pink sheen. And then the sun came up. It was red like it sometimes is at sunrise,

only it stayed red as it got to the middle of the sky, and it looked lumpy and saggy at the edges. Like a few of us, ha ha. Lumpy and sagging at the edges. A cold wind blowing across the

beach.”

“If you were sealed in the submarine, how did you know there was a cold wind?” Cynthia asked.

Jane glared at her. Nick said, “We could see the sand blowing around. And it looked cold. The grey ocean. Like winter.”

“Tell them about the crab,” said Jane.

“Yes, the crab. The last life-form on Earth. It wasn’t really a crab, of course, it was something about two feet wide and a foot high, with thick shiny green armor and maybe a dozen

legs and some curving horns coming up, and it moved slowly from right to left in front of us. It took all day to cross the beach. And toward nightfall it died. Its horns went limp and it stopped

moving. The tide came in and carried it away. The sun went down. There wasn’t any moon. The stars didn’t seem to be in the right places. The loudspeaker told us we had just seen the

death of Earth’s last living thing.”

“How eerie!” cried Paula.

“Were you gone very long?” Ruby asked.

“Three hours,” Jane said. “You can spend weeks or days at the end of the world, if you want to pay extra, but they always bring you back to a point three hours after you went.

To hold down the babysitter expenses.”

Mike offered Nick some pot. “That’s really something,” he said. “To have gone to the end of the world. Hey, Ruby, maybe we’ll talk to the travel agent about

it.”

Nick took a deep drag and passed the joint to Jane. He felt pleased with himself about the way he had told the story. They had all been very impressed. That swollen red sun, that scuttling crab.

The trip had cost more than a month in Japan, but it had been a good investment. He and Jane were the first in the neighborhood who had gone. That was important. Paula was staring at him in awe.

Nick knew that she regarded him in a completely different light now. Possibly she would meet him at a motel on Tuesday at lunchtime. Last month she had turned him down but now he had an extra

attractiveness for her. Nick winked at her. Cynthia was holding hands with Stan. Henry and Mike both were crouched at Jane’s feet. Mike and Ruby’s twelve-year-old son came into the room

and stood at the edge of the conversation pit. He said, “There just was a bulletin on the news. Mutated amoebas escaped from a government research station and got into Lake Michigan.

They’re carrying a tissue-dissolving virus and everybody in seven states is supposed to boil their water until further notice.” Mike scowled at the boy and said, “It’s after

your bedtime, Timmy.” The boy went out. The doorbell rang. Ruby answered it and returned with Eddie and Fran.

Paula said, “Nick and Jane went to see the end of the world. They’ve just been telling us about it.”

“Gee,” said Eddie, “We did that too, on Wednesday night.”

Nick was crestfallen. Jane bit her lip and asked Cynthia quietly why Fran always wore such flashy dresses. Ruby said, “You saw the whole works, eh? The crab and everything?”

“The crab?” Eddie said. “What crab? We didn’t see the crab.”

“It must have died the time before,” Paula said. “When Nick and Jane were there.”

Mike said, “A fresh shipment of Cuernavaca Lightning is in. Here, have a toke.”

“How long ago did you do it?” Eddie said to Nick.

“Sunday afternoon. I guess we were about the first.”

“Great trip, isn’t it?” Eddie said. “A little somber, though. When the last hill crumbles into the sea.”

“That’s not what we saw,” said Jane. “And you didn’t see the crab? Maybe we were on different trips.”

Mike said, “What was it like for you, Eddie?”

Eddie put his arms around Cynthia from behind. He said, “They put us into this little capsule, with a porthole, you know, and a lot of instruments and—”

“We heard that part,” said Paula. “What did you see?”

“The end of the world,” Eddie said. “When water covers everything. The sun and the moon were in the sky at the same time—”

“We didn’t see the moon at all,” Jane remarked. “It just wasn’t there.”

“It was on one side and the sun was on the other,” Eddie went on. “The moon was closer than it should have been. And a funny color, almost like bronze. And the ocean creeping

up. We went halfway around the world and all we saw was ocean. Except in one place, there was this chunk of land sticking up, this hill, and the guide told us it was the top of Mount

Everest.” He waved to Fran. “That was groovy, huh, floating in our tin boat next to the top of Mount Everest. Maybe ten feet of it sticking up. And the water rising all the time. Up,

up, up. Up and over the top. Glub. No land left. I have to admit it was a little disappointing, except of course the idea of the thing. That human ingenuity can design a machine that can send

people billions of years forward in time and bring them back, wow! But there was just this ocean.”

“How strange,” said Jane. “We saw the ocean too, but there was a beach, a kind of nasty beach, and the crab-thing walking along it, and the sun – it was all red, was the

sun red when you saw it?”

“A kind of pale green,” Fran said.

“Are you people talking about the end of the world?” Tom asked. He and Harriet were standing by the door taking off their coats. Mike’s son must have let them in. Tom gave his

coat to Ruby and said, “Man, what a spectacle!”

“So you did it, too?” Jane asked, a little hollowly.

“Two weeks ago,” said Tom. “The travel agent called and said, Guess what we’re offering now, the end of the goddamned world! With all the extras it didn’t really

cost so much. So we went right down there to the office, Saturday, I think – was it a Friday? – the day of the big riot, anyway, when they burned St Louis—”

“That was a Saturday,” Cynthia said. “I remember I was coming back from the shopping center when the radio said they were using nuclears—”

“Saturday, yes,” Tom said. “And we told them we were ready to go, and off they sent us.”

“Did you see a beach with crabs,” Stan demanded, “or was it a world full of water?”

“Neither one. It was like a big ice age. Glaciers covered everything. No oceans showing, no mountains. We flew clear around the world and it was all a huge snowball. They had floodlights

on the vehicle because the sun had gone out.”

“I was sure I could see the sun still hanging up there,” Harriet put in. “Like a ball of cinders in the sky. But the guide said no, nobody could see it.”

“How come everybody gets to visit a different kind of end of the world?” Henry asked. “You’d think there’d be only one kind of end of the world. I mean, it ends,

and this is how it ends, and there can’t be more than one way.”

“Could it be fake?” Stan asked. Everybody turned around and looked at him. Nick’s face got very red. Fran looked so mean that Eddie let go of Cynthia and started to rub

Fran’s shoulders. Stan shrugged. “I’m not suggesting it is,” he said defensively. “I was just wondering.”

“Seemed pretty real to me,” said Tom. “The sun burned out. A big ball of ice. The atmosphere, you know, frozen. The end of the goddamned world.”

The telephone rang. Ruby went to answer it. Nick asked Paula about lunch on Tuesday. She said yes. “Let’s meet at the motel,” he said, and she grinned. Eddie was making out

with Cynthia again. Henry looked very stoned and was having trouble staying awake. Phil and Isabel arrived. They heard Tom and Fran talking about their trips to the end of the world and Isabel said

she and Phil had gone only the day before yesterday. “Goddamn,” Tom said, “everybody’s doing it! What was your trip like?”

Ruby came back into the room. “That was my sister calling from Fresno to say she’s safe. Fresno wasn’t hit by the earthquake at all.”

“Earthquake?” Paula asked.

“In California,” Mike told her. “This afternoon. You didn’t know? Wiped out most of Los Angeles and ran right

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...