- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

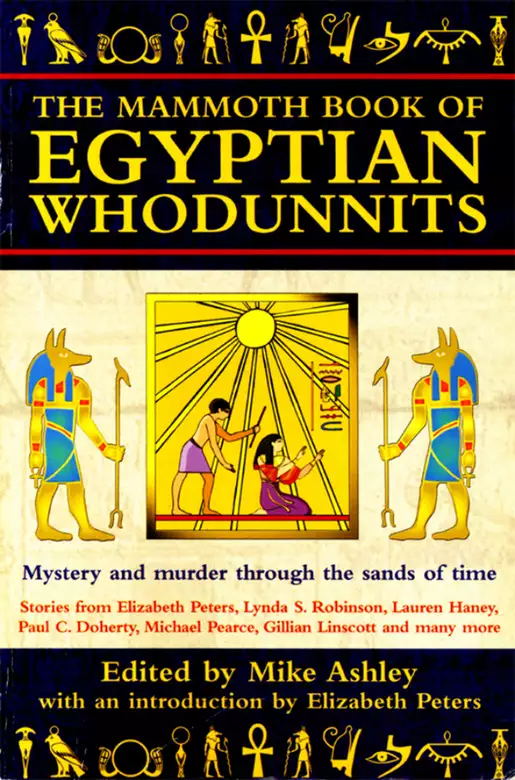

From Cleopatra and Herodotus to Howard Carter and the Curse of the Pharaohs, the investigators in The Mammoth Book of Egyptian Whodunnits uncover the murder mysteries of Ancient Egypt in over two dozen stories. Master anthologist Mike Ashley has gathered hidden gems and specially commissioned pieces from the genre's favorite practitioners like Elizabeth Peters, Suzanne Franke, Michael Pearce, and featuring such favorite ancient-world investigators as Lynda Robinson's Lord Meren, "the Eyes and Ears" of Nefertiti and Tutankhamun, Paul Doherty's judge Amerotke from the 18th Dynasty, and Lauren Haney's Lieutenant Bak of the Medjay police under Queen Hatshepsut, to beguile and confound historical mystery readers.

Release date: September 20, 2002

Publisher: Running Press

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Egyptian Whodunnits

Mike Ashley

And then there is the sheer immensity of time! The predynastic period dates from over 7,500 years ago. The earliest known kings ruled about 5,000 years ago and the first pyramids were built over 4,500 years ago. The Egyptian civilizations rose and fell and rose and fell again and again, yet there was a continuity stretching for some three thousand years, three times longer than England has existed and fifteen times longer than there has been a United States of America.

The Egyptian civilization had laws and rules like ours, rules that were just as easily broken and had to be enforced. The worst crime of all was that of tomb-robbing, which was deemed even more serious than murder. Theft was not an especially common crime – there were apparently few muggers or highwaymen. Tax evasion or non-payment of a debt was far more common, so some things have stayed the same. At the time of the New Kingdom the law was enforced by a group of mercenary soldiers known as the Medjay, but there had been a police force for centuries before, charged with guarding the mines and quarries and cemeteries.

This anthology takes us through the ages, and features whodunnits from the dawn of civilization, at the time of the first pyramids, through all the well-known rulers down to the time of Cleopatra. It also includes a few stories set during the early days of Egyptology from the Napoleonic period to the years just before the First World War, all of which draw upon the magic and mystery of ancient Egypt.

All of the major writers of Egyptian mysteries have contributed new material, from Elizabeth Peters to Lynda Robinson, and from Lauren Haney to Anton Gill and Michael Pearce.

The fascination with the magic of Egypt isn’t a recent phenomenon. It goes back at least as far as the ancient Greeks, whose historian Herodotus (who appears in one of the stories in this book) described the mysteries of Egypt in his travels and, in so doing, also described one of the world’s oldest mystery stories. The modern interest began in Napoleonic times with the growth of archaeology and the emergence of the science of Egyptology. The rediscovery of ancient Egypt began to fuel fiction, such as the work of Théophile Gautier in France, and mummy’s and Egyptian curses soon became a staple of horror fiction and macabre mysteries. The fascination in fiction really took off with the success of H. Rider Haggard’s books which evoked a mystique of lost times and other days.

Although I have encountered a few early short stories set in ancient Egypt involving a crime or a mystery, I don’t know of a genuine ‘whodunnit’ set wholly in ancient Egypt earlier than Agatha Christie’s Death Comes as the End, published in 1944. The story is set in around 2000 BC, though in fact reads every bit as cozy as a traditional country-house murder. Christie was married to the archeologist Max Mallowan and joined him on several archeological digs in the Middle East. Several of her stories are set in Egypt or involve an Egyptian theme, most notably “The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb” (1924) and the novel Death on the Nile (1937).

Despite setting a novel entirely in ancient Egypt, Christie’s work did not in itself set a trend for such works. In fact it was not until the current fascination for historical mysteries, in the wake of the Cadfael books by Ellis Peters, that several authors began series set in the Land of the Nile. These include Lynda Robinson’s novels set at the time of Tutankhamun and featuring the pharaoh’s inquiry agent, Lord Meren; Lauren Haney’s series featuring Lieutenant Bak of the Medjay Police during the reign of Queen Hatshepsut and Paul Doherty’s novels featuring Egypt’s principal judge, Amerotke, in the reign of Tuthmosis. All of these characters feature in new stories in this anthology.

All of the authors have endeavoured to make the stories fit into the known historical period. This occasionally means using special words and terms but, have no fear, they are all explained in each story.

The word you will encounter most is ma’at. Ma’at (with a capital M) was the goddess of truth and justice and represented harmony in the universe. She was the goddess in whose name the king ruled. If ma’at (small “m”) means order then the opposite, chaos, was represented by isfet, which also represents sin or violence. Then, as now, society was the constant tussle between ma’at and isfet.

Egypt was divided into a number of provinces. In later years these were called nomes, though that is a Greek word and the original Egyptian was sepat. There were 42 provinces, each governed by a nomarch. For a couple of hundred years (from the sixth to the twelfth dynasties) the nomarchs became hereditary rulers, but were eventually stripped of their power (see Keith Taylor’s story).

The ultimate rule of law was vested in the king, but it was delegated to a vizier, the equivalent of a modern day prime minister. Cases could be heard by a vizier but for all practical purposes each town had its own magistrate, the kenbet. The royal palace, which was the basis of all administration, was called the per-aa (or “great house”) and in later years the Greeks corrupted that word into pharaoh, the name we all associate with the king. The proper Egyptian word for king was suten.

The ancient Egyptians never called their country Egypt, of course. Their name for their land was Kemet, which means “black land”, because of the silt from the Nile which spread over the land during the annual inundation. The northern part of Egypt, around the Nile delta, is called Lower Egypt. This is where most of early kings ruled and where the main pyramid complexes were built, at Saqqara, Giza and Memphis. The southern part of Egypt is called Upper Egypt. This was the main home of the pharaohs in the Middle Kingdom and is the site of Thebes (also called Luxor) and the Valley of the Kings. If you continue further south along the Nile, you reach the first cataract at Aswan, which was the old boundary of Upper Egypt. Beyond that was Nubia, or the Land of Kush, also known as Wawat, roughly equal to modern Sudan.

And that’s about all you need to know. Now it’s my pleasure to hand over to Elizabeth Peters to declare this anthology open.

Mike Ashley

I spent the earliest years of my life in a small town in Illinois – and when I say “small”, I mean fewer than 2000 people. It was an idyllic sort of existence, I suppose, except for a few minor disadvantages like a nationwide Depression and the fact that my home town had no library. For a compulsive reader this was a tragedy more painful than the Depression. Luckily for me both my parents were readers. From my mother and a wonderful great-aunt I acquired most of the childhood classics and some classic mysteries. My father’s tastes were more eclectic. By the time I was ten I had read (though I won’t claim to have understood) Mark Twain, Shakespeare, Edgar Rice Burroughs, H. Rider Haggard, Sax Rohmer, Dracula and a variety of pulp magazines, to mention only a few. I don’t doubt that the sensational novels and magazines influenced not only my reading habits but my later plots. There was quite a lot in them about lost civilizations, ancient curses, and animated mummies.

Ancient Egypt has always been an inspiration to writers of sensational fiction. There is probably no other ancient culture so evocative and so seemingly mysterious. Bizarre animal-headed gods, monolithic temples, tombs filled with treasure . . . it’s great stuff, even if you know that the historic facts do not substantiate that view of Egyptian culture.

My love affair with the real Egypt began when that same wonderful great-aunt took me to the Oriental Institute Museum at the University of Chicago, in which city we lived at the time. Everyone should have a great-aunt like that; she considered it her duty to pound culture into the unwilling heads of her younger kin. After that experience I was no longer unwilling. It’s impossible to explain an obsession. That is what Egypt was for me, from then on. A goodly number of young people feel the fascination; it usually follows the dinosaur craze. Most of them grow out of it. I never did.

After graduating from high school I went to the University of Chicago – not because it had a world-famous department of Egyptology, but because it was close to home and I had received a scholarship. Practicality was the watchword. I was supposed to be preparing myself to teach – a nice, sensible career for a woman. I took two education courses before I stopped kidding myself and headed for the Oriental Institute. I studied hieroglyphs and other forms of the language, and got my doctorate when I was twenty-three.

Much good it did me. (Or so I believed for many years.) Positions in Egyptology were few and far between and, in the post-World War II backlash against working women, females weren’t encouraged to enter that or any other job market. I recall overhearing one of my professors say to another, “At least we don’t have to worry about finding a job for her. She’ll get married.” I did. And they didn’t.

During the next few years I did manage to get to Egypt several times, and each visit strengthened my initial fascination. I had given up the idea of a career in the field. Instead I had begun writing mystery stories, because I enjoyed them and I hoped to earn a little money. They were terrible. My first book to be published was not a thriller but Temples, Tombs and Hieroglyphs, A Popular History of Egyptology. It was followed by Red Land, Black Land, Daily Life in Ancient Egypt. Finally that degree had “paid off” – in a way I never expected. Perhaps I should have taken this as an omen, but I kept on writing mysteries and finally got one of them published. It was a “Gothic romance”, as they were erroneously called in those days, under the name of Barbara Michaels. The first book I wrote under the Peters pseudonym proved I hadn’t got Egypt out of my system. It was a contemporary thriller, The Jackal’s Head, without any of the appurtenances of supernatural fiction; but there was a lost tomb and a golden treasure and considerable skullduggery.

It has taken me over a quarter of a century to realize that I love to write, and that that career is the one I should have pursued from the beginning; but my obsession with Egypt has not faded and I doubt it ever will. I go “out”, as we say in the trade, at least every other year, and I use my training and my experience in what is probably my most popular mystery series, written under the Peters name: the saga of Victorian archaeologist Amelia Peabody, who has been terrorizing 19th-century England and Egypt through fourteen volumes (so far). The effects of my childhood reading linger; Amelia has encountered walking mummies and found lost tombs and lost civilizations. The books are fantasies in that sense, but they are soundly grounded in fact and they give me the best of two possible worlds. I collect Egyptological fiction, and attend every film featuring archaeologists, good and the bad. Some of the books are very bad indeed – not because of the wildness of the author’s invention but the ineptitude of plotting and style. The wilder the better, say I. One can never have too many mummies.

One of the great geniuses of the ancient world was Imhotep. He was the vizier of the Third Dynasty king, Djoser, and the architect responsible for the construction of Djoser’s tomb, known as the Step Pyramid. That pyramid complex, at Saqqara, was constructed around 2650 BC and was the first known stone building in the world. The following story takes place in Imhotep’s old age but refers back to an incident in his youth. Most of the characters named actually existed, including Peseshet who, like Imhotep, was a physician. She became the “overseer” or director of female doctors.

Deirdre Counihan comes from a literary family. Her grandfather was the prolific writer W. Douglas Newton. Her father, Daniel Counihan, was a writer, painter, journalist and broadcaster and her mother, Joan, is an historian. With her sister, Liz (who is also a writer – see my anthology Mammoth Book of Seriously Comic Fantasy) they produce a small literary magazine, Scheherazade. Previously a teacher, Deirdre is a specialist in art and art history, particularly archaeological art, and runs an artist’s Open House.

Mid-morning of the second day after their arrival, they found Udimu dead.

His nursemaid had missed him at first light, but finally found him when the ape Huni ran screaming out of the garden latrine. Small white feet and little legs down to the knees protruded from the sandbox; the rest of him was crammed incongruously inside. Horrified, the two gardeners looked at each other and then, taking one small leg each, hauled him out.

They laid him on the mud floor, the favourite son, to await Lord Kanofer, his father. His pathetic lock of childhood hair swung to one side as his head lolled backwards. They saw that his throat had been slit from ear to ear, but a length of fine linen had been rammed into his mouth, so hard that some of it protruded through the jagged cut. His pointed child’s face was bloated by his agony, his lips forming a rigid circle of horror, drawn back from the pearly milk teeth. His eyes were closed. His chubby infant fingers gripped into the fists of his final agony.

“Ah, no! This cannot be – he is just a baby!” The desperate nursemaid wrung her hands in horror. “Who would do such a thing?”

“Udimu? Have you found him?” His three older sisters came hurrying up, gathering round the door of the latrine, peering in and then falling back in disbelief. Peseshet, the eldest, broke through the others and knelt down beside the pathetic body. She dabbed at the jagged end of the cut with the edge of her kilt.

“Poor beautiful, baby – you that are always so pale.” Tenderly, she eased open the tiny clenched fist. “Ah see!” Her voice broke. “Here is a bit of his sleepy-shawl – he would never go to bed without it – they must have wrenched it from him!”

“He is dead?” The baby’s other sisters, Intakes and Meresank, had now been allowed through the throng of horrified servants. “This is insane.”

“Someone has cut his throat, poor little ka.”

“This must be the razor that did it!” Intakes stood poised, not daring to bend down and touch it, but pointing to something that lay further into the darkened hut. “I think it may be Father’s.”

“Oh, don’t be crazy.” Meresank was sobbing uncontrollably. “It could be anyone’s! Hasn’t anybody been sent to fetch Father and our brother Imhotep and the doctor? We shouldn’t be touching anything till they get here.”

“Insanity on insanity,” wept Peseshet. “There is the razor, but where is all the blood?”

Someone had recaptured the pet ape Huni, and he stood whimpering, tied to a palm by the walkway. And maybe he was the only one of them that knew that this was not the first murder in the family he had witnessed – if he understood what murder was.

It was fresh mid-morning – still too early for polite visiting – but the young Royal Physician Iry was received with all the deference due to one permitted to touch the body of God. As impeccable servitors ushered him through the vast, faded opulence of Imhotep’s family mansion, Iry found himself, yet again, astonished that someone with the taste and austerity of this venerable lord should continue to live there.

There was no one in the two kingdoms of Egypt whom Iry revered more than this increasingly frail old man. While the inspiration of Imhotep’s thought reigned proverbial on every lip, and all stood in awe before the breathtaking splendour of the sacred edifices that it had been his to mastermind, Iry, uniquely, understood that while his own powers as a physician were a remarkable gift from the gods, they paled into insignificance when compared to those of this discreetly dying gentleman.

Iry was ushered through the great studio – scale models, the fruits of Lord Imhotep’s life of labour for the royal family and the gods, lay everywhere bathed in the amber mote-flecked silence. A sudden beam of golden light from the garden came flooding over the masterpiece, Great Djoser’s pyramid tomb, stepped in stone and pointing to heaven.

Iry drew a breath of awe – today, over on the far banks of the river, its vast completion stood surrounded by the pyramids of those lesser deities, Djoser’s descendants, all set in stone for eternity. This workshop of vacillations attested to the patience and forbearance with which Imhotep the wise, over the years, had conducted them on their path towards immortality.

The light glanced across the statue of Thoth, benign in baboon form, naturally presiding over any such place of endeavour. “O Thoth, grant me wisdom like Imhotep,” begged Iry. “Steer me lest I offend or hurt him!” For that great old gentleman – showing no professional or family jealousy – had once steered Iry towards the exalted position of service that he held today, always reminding him that service must be pivotal to everything he did.

Now, in the course of that service, Iry was obliged to perform a most distasteful task. Something His Sacred Majesty had been reading in the royal archives had intrigued him – something on which Lord Imhotep could likely shed some light!

“He will fall for your honey-tongue, Iry!” the fascinated Pharaoh had decided. “Everyone knows he respects your integrity!”

Doctor Iry shuddered. Nothing was less likely in this case. If Lord Imhotep had considered something better left unrecorded for all these years, he had good reason – better reason than serving as salacious entertainment for a bevy of inquisitive young princesses, which was probably the real driving motive behind the royal interest. Righting uncovered wrongs, somehow, did not ring true from King Huni.

All too soon the young doctor found himself sitting nervously by the cool tranquillity of Imhotep’s lily-covered pond. Things were not going well. At any moment, Iry sensed, his lordship’s legendary restraint could be in jeopardy.

“So, his majesty has finally taken to a quest for knowledge!” Imhotep sat, taut and fastidious in his cushioned chair. “But what wonder of Earth or stars succeeds in prompting him? A disgusting family murder, best forgotten – thoroughly investigated years ago! Why, I was scarcely a boy at the time!”

“But . . .”

“Contrary to popular belief, I do not know everything,” hissed the old man; then, suddenly, he smiled. “You know, Iry, they even say I leapt from the womb issuing instructions to the midwife! Such nonsense. Why does the king imagine I might have any important observations concerning such ancient darkness?”

But Iry’s imagination was awash with crimson – the blood of a two-year-old with a slit throat. “Obviously his majesty has read what exists about the case,” Iry gulped. “He knows who the culprit was said to be – but it was not a simple death – he feels there cannot be so simple an answer. I was astonished to be told the murdered child was one of your brothers . . .”

“My only brother; Udimu was my half-brother. My father had two wives.”

“Truly, I did not appreciate that! Royalty – you constantly confuse me!”

“Ah, Iry – how deftly you flatter, these days – but we were only fringe royalty. Like you, our duty lay in serving those at its core.”

“And were you happy? I had always found your family such an inspiration. Could such horror have been foreseen?”

“Foreseen? Yes, we were, originally, a very happy family, my elder sisters Peseshet, Intakes, Meresank and I. We were the children of peace after all those years of civil strife. Our dashing father, Kanofer, had risen through it all by his talents. Our dear mother, Princess Redyzet, was a half-sister to the Great Queen Nemaathap.”

“Indeed, it is the records of her inquisitors that have captured Pharaoh’s imagination!”

“Then I need hardly remind you that this beautiful and wise lady enshrined the royal blood-line. Originally she was married to the king, their father, and was mother of our favourite young uncle/cousin, Crown Prince Djoser.

“But the old king, my grandfather, suddenly died. To everyone’s surprise – but presumably hoping to avoid the sort of anarchy that having a child-king can bring – Queen Nemaathap chose to marry her only half-brother, Senakhte, thus making him the new Pharaoh.

“To be able to do this, my half uncle Senakhte quite ruthlessly divorced his seemingly barren wife Lady Heterphernebti – who was a particular friend of Mother’s. My sympathetic parents rushed to provide a loving home for her and her disturbingly light-fingered pet ape (whose name, if I recall aright, was Huni), and so all our troubles began.”

“Heterphernebti – not a name that I recall from the transcripts. And as for the ape . . . !”

“But crucial – his majesty may not be wrong, possibly much lies unrecorded – probably better so. Well, my two younger sisters took to our ex-aunt at once, but the eldest, Peseshet, and I could never really trust her. Within the family, Heterphernebti and Senakhte held a clouded reputation, hints of intrigue around the throne – but now she was stranded high, dry and very bitter. You would think that a rich commoner would have expected no less.

“But the royal barns groaned with produce to preserve the land from famine and the royal nursery was filling with half-sisters for our beloved Prince Djoser, so the gods clearly endorsed Senakhte’s stark decision (anyway, that was what Peseshet and I were amused to conjecture).

“Innocent days! Father, now Royal Supervisor of Works, would take me out with him at each fecund brown Inundation to inspect construction – and I learnt the months and years of careful preparation needed for any plan to reach fruition.

“At harvest time when this labour ceased, we always sailed down to our Southern estates, where my father had been born.”

“Where your brother was done to death?”

“Indeed. Then one year brought another newcomer to my parents’ household – her name was Miut – kitten. She had a remarkable story.”

“That name is mentioned!”

Imhotep paused and Iry fancied a slight smile creased his mouth.

“This stranger, Miut, strode into my father’s fields, claiming to be the wife of one of our tenants, Bedjames – met while undertaking a distant voyage for Pharaoh, but now gone missing. To my adolescent eyes – I was just into my eleventh year – the most striking thing about her was that, unlike the rest of the field workers who were sensibly naked, this young woman kept herself covered. A superb shawl was wrapped clingingly around her most curving parts – ‘stolen, no doubt,’ Mother laughingly observed – yet Mother and her perpetual guest, Heterphernebti, acquired shawls of equal quality at the soonest opportunity!”

“Quite so, my lord, but . . .”

“But keep to the point, eh, Iry? Lady Heterphernebti expressed great sympathy for this abandoned wife and so Miut joined our household while we investigated whose responsibility she was. She became a favourite with everyone.

“But dear, beautiful Mother’s health was starting to give us concern. Poor Peseshet was studying to be a female doctor and was desolate at proving unable to help her. Lady Heterphernebti, assisted by Miut (who had wonderful ways with headaches), was all solicitude. It was Heterphernebti’s hand that mother held, not my father’s, not mine, in her final moments. I have never, ever, recovered from the desolation of that thought.”

Imhotep paused, and Iry noticed his eyes had moistened.

“And so to Udimu. The swiftness with which Father and Heterphernebti chose to marry after Mother’s death and the arrival, scarcely eight months later, of my little brother, was a shock for everyone. Heterphernebti had been considered barren, old, yet here she was producing a child, and a child phenomenon at that.”

“I see the complexity of it! Tell me more about Udimu.”

“Many of the exaggerated tales that have been put about concerning my birth and earliest years have probably originated in real stories of my pale new brother. He was born with teeth, he could talk well before he could crawl – and he was crawling early too. He was like a young adult even before he was three. ‘This is a full-term baby!’ Peseshet insisted at the birth, daring to voice what none of the other women wanted to consider – that Udimu had been conceived well before his parents’ marriage or Mother’s death.

“So the notion that my sister Peseshet hated Udimu started the moment he was born – everyone knew she remained irreconcilable to the circumstances of Mother’s passing. However, I can affirm that with the rest of us, Intakes, Meresank and I, she was fascinated by, and rather proud of our new brother.

“Heterphernebti found the joint roles of Lord Kanofer’s consort and happy new mother draining. Though Father ensured that she was pampered and cosseted, she preferred only Miut in attendance to soothe her head. The other maidservants were needed to monitor poor Huni, the pet ape, who could not decide if Udimu was meant to be some new toy to be dismembered or some titbit to be eaten!”

“But was Udimu such a truly remarkable child, my lord?” Iry tried to steer the old man back to the point. “Pharaoh particularly wanted to understand this – the death was so thorough, so brutal – three different ways! You were such a brilliant family, did he so outshine you all?”

“Absolutely! A complete enigma – from his earliest words, we never heard him make a grammatical error, yet he was baby enough to require a neatly hemmed section of his mother’s expensive shawl to comfort him to sleep.

“He loved to be told stories; he didn’t mind if they were truth or fiction, but he understood the difference, which astounded me because one of our favourite family diversions was convincing poor Intakes of complete nonsense. She used to look so like Mother when she opened her eyes wide in wonder, it was almost like having her back, laughing amongst us. Everyone joined in the task of keeping Udimu captivated – and stayed to be captivated as well.

“Miut’s tales were the ones that held the biggest audience. Prince Djoser, and sometimes other friends and relatives, would sit enraptured here under the stars as she described her epic journey and the astonishing things that she claimed she had witnessed – perhaps, strangest of all, in her own land, a well that could turn any object into stone. You could give a leaf eternal life, she said, or preserve a flower forever.

“Prince Djoser was deeply taken by that notion of eternal stone, but Udimu became obsessed. He would build tiny stone casings for the spent flowers that dropped here on the garden pathways, in hopes to keep them fresh forever. He wanted to tell stories too. One evening, when most of the family were gathered here by the pool, he said to us:

“ ‘Last night I had a dream that I was a little bird, but Imhotep was a big bird, and I flew under the shadow of his wing. At the edges of the earth, we were met by a vast, golden ship, hauled on golden ropes by a crowd of golden men. Imhotep and I perched on the ship and it took us deep into darkness until we stopped at a huge gate. I peeped out from under Imhotep’s wing and saw that the gateway was made of writhing bodies, and that the gatepost was turning in the socket of a lady’s eye. Everyone got off, and we went into a vast hall alive with flames. In the middle were some huge golden scales and a big black dog and the most lovely golden feather.’ ”

“Incredible!”

“Yes – we were all shaken – could someone his age know about ‘The Boat Of A Million Years’ and the judgment hall of heaven? Whose heart was about to be weighed against the Feather of Truth on the scales of Anubis? Was Udimu a seer on top of everything else?”

“Yes . . . his majesty was wondering . . .”

“But Udimu had not quite finished. ‘I thought I would try to fly down and pick up the pretty feather, only Nurse woke me up. But that lady who was lying with the gatepost through her eye – she looked like Intakes.’ The effect of this on poor Intakes was terrible – she fled in tears, followed by the other girls. Father and Heterphernebti were ashen-faced. Miut sat very still, hunched in her shawl – she recognized a dream of power when she heard it.”

“Only the immediate family were there?”

“On that particular occasion – but Father tried to discourage Udimu from story-telling after that. Poor baby, he was just approaching his third summer, when we set off up-river for the most tragic harvest of our lives.

“Mid-morning of the second day after our arrival, they found Udimu dead. His nursemaid missed him at first light, but they only finally found him when the ape Huni ran screaming out of the garden latrine.”

Imhotep drifted into silence and Iry wondered whether he had fallen asleep. The two sat quietly for some while, Iry listening to the laboured breathing of this most

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...