- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

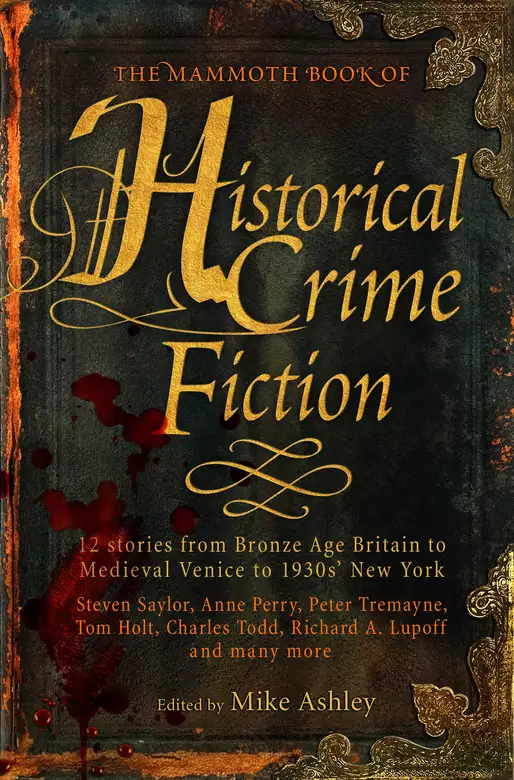

Our dark past brought to life by leading contemporary crime writers A new generation of crime writers has broadened the genre of crime fiction, creating more human stories of historical realism, with a stronger emphasis on character and the psychology of crime. This superb anthology of 12 novellas encompasses over 4,000 years of our dark, criminal past, from Bronze Age Britain to the eve of the Second World War, with stories set in ancient Greece, Rome, the Byzantine Empire, medieval Venice, seventh-century Ireland and 1930s' New York. A Byzantine icon painter, suddenly out of work when icons are banned, becomes embroiled in a case of deception; Charles Babbage and the young Ada Byron try to crack a coded message and stop a master criminal; and New York detectives are on the lookout for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Deirdre Counihan, Tom Holt, Dorothy Lumley, Richard A. Lupoff, Maan Meyers, Ian Morson, Anne Perry, Tony Pollard, Mary Reed and Eric Mayer, Steven Saylor, Charles Todd, Peter Tremayne

Release date: August 18, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Historical Crime Fiction

Mike Ashley

Tom Holt is best known for his many humorous fantasy novels, which began with Expecting Someone Taller (1987) and include Who’s Afraid of Beowulf? (1988), Paint Your Dragon (1996) and The Portable Door (2003) – the last heralding the start of a series featuring the magic firm of J. Wellington Wells from Gilbert and Sullivan’s light opera The Sorcerer. But Holt is also a scholar of the ancient world and has written a number of historical novels including The Walled Garden (1997), Alexander at the World’s End (1999) and Song for Nero (2003).

The following story, which is the shortest in the anthology and so eases us in gently, features one of the best known of the ancient Greek scientists and mathematicians, Archimedes. He lived in the third century BC in the city of Syracuse, in Sicily, under the patronage of its ruler Hieron II. It is a shame that the one enduring image we all have of Archimedes is of him leaping out of his bath shouting “Eureka”, meaning “I have found it.” But it does encapsulate how Archimedes operated. When presented with a scientific problem he applied his whole self to it using scientific principles, many of which he had propounded. Archimedes unified much scientific theory into a coherent body of thought which allowed him to apply what he regarded as the scientific method. It probably made him the world’s first forensic investigator.

“No,” I told him. “Absolutely not.”

You don’t talk like that to kings, not even if they’re distant cousins, not even if they’re relying on you to build superweapons to fight off an otherwise unbeatable invader, not even if you’re a genius respected throughout the known world. It’s like the army. Disobeying a direct order is the worst thing you can possibly do, because it leads to the breakdown of the machine. You’ve got to have hierarchies, or you get chaos.

He looked at me. “Please,” he said.

He, for the record, was King Hiero the Second of Syracuse; my distant cousin, my patron and my friend. Even so. “No,” I said.

“Forget about the politics,” he said. “Just think of it as an intellectual problem. Come on,” he added, and that little-boy look somehow found its way back on to his face. Amazing, how he can still do that, after the life he’s lived. “You’ll enjoy it, you know you will. It’s a challenge. You like challenges. Isn’t that what it’s all about, finding answers to questions?”

“I’m busy,” I told him. “Really. I’m in the middle of calculating the square root of three. If I stop now—”

“The what of three what?”

“I’ll lose track and have to start all over again. Four years’ work, wasted. I can’t possibly drop that just to help out with some sordid little diplomatic issue.”

One of these days, people tell me, one of these days I’ll get myself into real trouble talking to important people like that. Don’t be so arrogant, people tell me. Who do you think you are, anyhow?

“Archimedes.” He wasn’t looking at me any more. He was staring down at his hands, folded in his lap. It was then I noticed something about him that I’d never realized before. He was getting old. The bones of the huge hands stood out rather more than they used to, and his wrists were getting thin. “No,” I said.

“You never know,” he went on, “it might lead to a great discovery. Like the cattle problem or the thing with the sand. Those were stupid little problems, and look where they ended up. For all you know, it could be your greatest triumph.”

I sighed. You think somebody knows you, and then they say something, and it’s obvious they don’t. “No,” I said. “Sorry, but that’s final. Get one of your smart young soldiers on to it. That Corinthian we had dinner with the other evening; sharp as a razor, that one; I’m sure he’d relish the chance to prove himself. You want someone with energy for a job like this. I’m so lazy these days I can hardly be bothered to get out of bed in the morning.”

He looked at me, and I could see I’d won. I’d left him no alternative but to use threats – do this or it’ll be the worse for you – and he’d decided he didn’t want to go there. In other words, he valued our friendship more than the security of the nation.

“Oh, all right,” I said. “Tell me about it.”

*

The extraordinary thing about human beings is their similarity. We’re so alike. Dogs, cows, pigs, goats, birds come in a dazzling array of different shapes and sizes, while still being recognizable as dogs, cows, pigs, goats, birds. Human beings scarcely vary at all. The height difference between the unusually short and the abnormally tall is trivial compared with other species. The proportions are remarkably constant – the head is always one-eighth of the total length, the width of the outstretched arms is always the same as the length of a single stride, and the stride is so uniform that we can use it as an accurate measurement of distance. Human beings have two basic skin colours, three hair colours, and that’s it. Just think of all the colours chickens come in. It’s a miracle we can ever tell each other apart.

That said, I can’t stand Romans. They’re practically identical to us in size, shape, skin and hair colour, and facial architecture. Quite often you can’t tell a Roman from a Syracusan in the street – no surprise, when you think how long Greeks and Italians have shared Sicily. I’ve known Romans who can speak Greek so well you wouldn’t know they weren’t born here; not, that is, unless you listen to what they actually say.

It’s ridiculous, therefore, to take exception to a subsection of humanity that’s very nearly indistinguishable from my own subsection; particularly foolish when you consider that I’m supposed to be a scientist, governed by logic rather than emotion, and by facts susceptible to proof rather than intuition and prejudice. Still, there it is. I can’t be doing with the bastards, and that’s all there is to it.

Partly, I guess, my dislike stems from the fact that they’re taking over the world, and nobody seems willing or able to stop them. Hiero tried, and he couldn’t do it. They smashed his Carthaginian allies, and he was forced to snuggle up and sign a treaty with the Roman smile and the Roman hobnailed boot. Not sure which of those I detest most, by the way. Probably the smile.

Needless to say, the problem Hiero had just blackmailed me into investigating was all about Romans. One Roman in particular. His name was Quintus Caecilius Naso, diplomatic attaché to the Roman delegation to the court of King Hiero, and what he’d done to make trouble for Syracuse (and perplexity for me) was to turn up, extremely dead, in a large storage jar full of pickled sprats, on the dockside at Ostia, when he should have been alive and healthy in the guest quarters of the royal palace at Syracuse.

Quintus Caecilius Naso – why Romans have to have three names when everybody else manages perfectly well with one is a mystery to me – was, at the time of his death, a thirty-six-year-old army officer, from a noble and distinguished family, serving as part of a delegation engaged in negotiating revisions to the treaty Hiero had been bounced into signing twenty years ago; in other words, he was here to bully my old friend into making yet more concessions, and I know for a fact that Hiero was deeply unhappy about the situation. However, he’d managed to claw back a little ground, and it looked as though there was a reasonable chance of lashing together a compromise and getting rid of the Romans relatively painlessly, when Naso suddenly disappeared.

I never met the man, but by all accounts he wasn’t the disappearing sort. Far too much of him for that. He wasn’t tall, but he was big; a lot of muscle and a lot of fat was how people described him to me, just starting to get thin on top, a square jaw floating on a bullfrog double-chin; incongruously small hands at the end of arms like legs. His party trick was to pick up a flute-girl with one hand, lift her up on his shoulder and take her outside for a relatively short time. He was never drunk and never sober, he stood far too close when he was talking to you, and he had, by all accounts, a bit of a temper.

He was last seen alive at a drinks party held at his house by Agathocles, our chief negotiator. It was a small, low-key affair; three of ours, three Romans, four cooks, two servers, two flute-girls. Agathocles and his two aides drank moderately, as did two of the Romans. Naso got plastered. Since he was the ranking diplomat on the Roman side, very little business was transacted prior to Naso being in no fit state; his two sidekicks clearly felt they lacked the authority to continue when their superior stopped talking boundaries and demilitarized zones and started singing along with the flautists and our three were just plain embarrassed. When Naso grabbed one of the girls – he dropped her, and had to use both hands – and wandered off into the courtyard with her, the rest of the party broke up by unspoken mutual consent and went home. Agathocles went into the inner room to bed. The Romans’ honour guard – a dozen marines from the ship they arrived on – stayed where they were, surrounding the house. Their orders were to escort Naso back to the palace. But Naso didn’t appear, so they stood there all night, assuming he’d fallen asleep somewhere. They were still standing there, at attention, when the sun rose. At this point, Naso’s secretary came bustling up; the great man was due in a meeting, where was he? The guards didn’t have the authority to wake him up, but the secretary did. He went inside, then looked round the courtyard, which didn’t take long. No sign of Naso, or the wretched girl. The secretary then made the guards search Agathocles’ house. Nothing.

The secretary and the guard-sergeant had a quick, panic-stricken conference and decided that Naso must’ve slipped past the guards with the girl – why he should want to do that, neither of them could begin to imagine – and was presumably shacked up with her somewhere, intending to re-emerge in his own good time. This constituted a minor diplomatic insult to us, of course, since the meeting had to be adjourned, and our side came to the conclusion that it was intended as a small act of deliberate rudeness, to put us in our place. If we made a fuss about it, we’d look petty-minded. If we said nothing, we’d be tacitly admitting we deserved to be walked all over. It was just the sort of thing Naso tended to do, and it had always worked well for him in the past.

But Naso didn’t show up; not for three weeks. The atmosphere round the negotiating table quickly went from awkward to dead quiet to furiously angry. What had we done with Caecilius Naso? A senior Roman diplomat doesn’t just vanish into thin air. It really didn’t help that Agathocles had been the host. He’d been doing his job rather well, digging his heels in, matching the Romans gesture for gesture, tantrum for tantrum; angry words had been spoken, tables thumped, and then Agathocles had asked Naso round for drinks and Naso had disappeared. Without him, the talks simply couldn’t continue. Ten days after the disappearance, the Roman garrisons on our borders mobilized and conducted unscheduled manoeuvres, as close to the frontiers as they could get without actually crossing them. Cousin Hiero had his soldiers turn the city upside down, but they found nothing. The Roman diplomats went home without saying goodbye. Their soldiers stayed on the border. Then, just as we were starting to think it couldn’t get any worse, Naso turned up again.

He made his dramatic re-entry when the swinging arm of the crane winching a great big jar of sprats off the bulk freighter snapped, on the main dock at Ostia, in front of about a thousand witnesses. The jar fell on the stone slabs and smashed open, and out flopped Naso. He was still in the full diplomatic dress he’d worn to the party, so it was immediately obvious that he was someone important in the military. He was quickly identified, and a fast courier galley was immediately launched, to tell us the bad news.

*

“Presumably,” Orestes said, “it was the extra weight that snapped the crane. A man’s got to weigh a damn sight more than his own volume in sprats.”

Orestes was the bright young Corinthian I’d proposed as my substitute. Instead, he’d been assigned to me as sidekick-in-chief. He was tall, skinny, gormless-looking and deceptively smart, with a surprisingly scientific cast of mind. “So what?” I said.

He offered me a drink, which I refused, and poured one for himself. My wine, of course. “This whole sprat business,” he said. “It’s got to mean something, it’s too bizarre otherwise.”

“Bizarre, I grant you,” I said. “But meaningful …”

“Has to be.” He nodded firmly. “Abducting and murdering a Roman emissary at a diplomatic function,” he went on, “has got to be a statement of some kind. Bottling him and sending him home must, therefore, be a refinement of that statement.”

“Expressive of contempt, you mean.”

“Must be.” He frowned at his hands. A nail-biter. “That’s not good for us, is it?”

“The crane,” I reminded him.

“What? Oh, right. I was just thinking, the timing of the discovery of the body. If the crane hadn’t broken, the jar would’ve been loaded on a cart and taken to Rome. It had been ordered by—” He looked up his notes. “Philippus Longinus,” he recited, “freedman, dealer and importer in wholesale foodstuffs. Disclaims all knowledge, et cetera. They’ve got him locked up, of course.”

“Greek?”

“Doesn’t say,” Orestes replied, “but he’s a freedman with a half-Greek name, so presumably yes. Loads of Greek merchants in Rome nowadays. Anyhow, in the normal course of business that jar of sprats would’ve stayed in his warehouse for months.” His eyebrows, unusually thick, lowered and squashed together. “Which makes no sense.”

I nodded slowly. “If you’re right about the murder as a statement,” I replied.

“Unless,” Orestes went on, looking up sharply, “whoever did it knew the extra weight would break the crane, in which case—” He looked at me, and sighed. “A bit far-fetched?”

“As wine from Egypt,” I said. “Of course,” I went on, “someone could’ve sawed the beam part-way through.”

“That’s—” He looked at me again. “You’re teasing me,” he said.

“Yes.”

“Fine. In that case, it makes no sense.”

“If,” I reminded him, “we approach the problem from the diplomatic-statement direction, as you seem determined to do.”

He gave me a respectfully sour look. “In the circumstances …”

He had a point, of course. “It would seem logical to assume that it’s something to do with politics and diplomacy,” I conceded.

“Exactly. So we should start from there.” I sighed. “No,” I said. “We should start from the beginning.”

*

We took a walk. On the way there, we discussed various topics – Pythagoras, the nature of light, the origin of the winds – and paused from time to time to let me rest my ankle, which hasn’t been right since I fell down the palace steps. We reached Agathocles’ house just before midday, a time when I was fairly sure he’d be out.

“I’m sorry,” the houseboy confirmed. “He’s at the palace. Can I tell him who called?”

“We’ll wait,” I said firmly.

*

Of course I’d been there before, many times. I knew that Agathocles lived in his father’s old house, and his father had been nobody special, a cheese merchant who was shrewd enough to buy into a grain freighter when the price was right, and then reinvest in land so his son could be a gentleman. I can only suppose Agathocles liked the place; happy childhood memories, or something of the sort. It was a small house, surrounded by a high wall, on the edge of the industrial quarter. If you stood on the street outside the front door, you could smell the tannery round the corner, or the charcoal smoke from the sickle-blade factory, or the scent of drying fish on the racks a hundred yards north. An unkind friend described it as pretentiously unpretentious, and I’m tempted to agree. Inside, you could barely move for statues, fine painted pottery, antique bronze tripods. It looked rather more impressive than it was because the rooms were so small, but even so, the collection represented a substantial amount of money, leaving you in no doubt that the great man lived where he did because he wanted to, not because he couldn’t afford anything better.

It was an old-fashioned house, too; rounded at one end, with two main rooms, for living and sleeping. The upstairs room, more of a storage loft than a gentleman’s chamber, was presumably a legacy of Agathocles’ father’s business activities, a dry and airy place to store cheeses, with a door opening into thin air, like you see in haylofts. The house stood in the middle of a larger-than-usual courtyard, half of which had been laid out as a garden, with trellised vines and fruit trees, herb beds and an ostentatious row of cabbages. The other half, shaded by a short, wide fig tree, was for sitting and talking in, and a very attractive space it made. It was surrounded, as I just told you, by a wall, and the reports said that on the fatal evening, the guards had stood all round the outside of the wall, with a sergeant minding the gate.

“Not good,” Orestes said sadly. “Not good at all.”

I concurred. I could see no way in which anyone could have scaled the wall – coming in or going out – without being seen by the guards, even in the dark; also there were sconces set in the wall for torches, and hooks for lanterns, and the report said that the courtyard had been lit up that night. Well nigh impossible, therefore, for Naso to have slipped out past the guards; equally implausible that anyone else could have climbed in to kill him.

“Bad,” Orestes said.

“Quite. If Naso was killed—”

He looked at me. “If?”

“If,” I repeated, then shrugged. “It must have been one of the people in the house at the time. Agathocles, his two aides, the two Romans, or the domestics. As you say,” I added, “bad for us.”

Orestes walked to the foot of the wall and stood on tiptoe. “Then how did they get rid of the body?” he said.

I smiled. “That,” I said, “is probably the only thing standing between us and war.”

He jumped up, trying to grab the top of the wall. He was a tall man, like I said. He couldn’t do it. “Maybe they hid the body,” he said, “and came back later.”

I shook my head. “Naso’s secretary and the guard-sergeant searched the house,” I reminded him. “And it’s not like there’s many places you could hide a body. I’m morally certain that Naso was off the premises when the house was searched.”

“But the guards were still in place. They’d have noticed.”

“Yes,” I said, and sat down, slowly and carefully, under Agathocles’ rather splendid fig tree. My neck isn’t quite as supple as it used to be, so I couldn’t lean back as far as I’d have liked.

“You think,” Orestes interpreted, “the body was in the tree?”

I smiled at him. “The outer branches overhang the wall,” I said, “And it’s a fact that when people are looking for something, they quite often don’t bother to glance up. But no, I don’t think so. Even if you were standing in the upstairs door—”

“What? You know, I hadn’t noticed that.”

“Which proves my point,” I said smugly. “You didn’t look up. I noticed that door as soon as I walked though the gate, but I don’t think it’s relevant in any way. It’s nowhere near the wall, and it’s too far for anybody, even a really strong man, to throw a dead body from there to the tree.” I frowned, as a thought slipped quietly into my mind, like a cat curling up on your lap. “We ought to take another look inside,” I said. “I believe our problem is that we’ve been searching for what isn’t there rather than paying due attention to what is. Also,” I added, “we suffer from the disadvantage of noble birth and civilized upbringing.”

“What does that mean?”

“I’m not sure,” I replied. “I’ll tell you when I’ve worked it out.”

*

We snooped round the house for a while, ending up in the upstairs room. Nothing obvious had caught my eye; no bloodstains, or tracks in the dust to show where a body had been dragged. I sat down on an ancient cheese press, while Orestes sat at my feet on a big coil of rope, the image of the great philosopher’s respectful disciple. That made me feel like a complete fraud, of course.

“A grown man,” I said, “walks out of a drinking party—”

“Staggers out of a drinking party.”

“True,” I said. “But he was used to being drunk. And he took the flute-girl. What about her, by the way?”

“What about her?”

“Has she turned up? Or has nobody thought to ask?”

Orestes shrugged. “I expect that if she’d been found they’d have held her for questioning.”

That made me frown. Call me squeamish if you like; I don’t like the notion, enshrined in the law of every Greek city, that a slave’s evidence can only be admissible in a court of law if it’s been extracted under torture. It gave the wretched girl an excellent motive for running away, that was for sure – assuming, that is, that she knew that something bad had happened, and she was likely to be wanted as a witness. “Let’s consider that,” I said. “I’m assuming Hiero’s had soldiers out looking for her.”

Orestes grinned. “Fair enough. I wouldn’t imagine it’d be an easy search. For a start, how would they know who to look for?”

I raised an eyebrow. “Explain,” I said.

“One slave-girl looks pretty much like another.”

“But her owner—” I paused. “Who owns her? Do we know?”

Orestes took another look at his notes. “One Syriscus. Freedman, keeps a stable of cooks and female entertainers, hires them out for parties and functions. Quite a large establishment.”

I nodded. “So it’s not certain that Syriscus himself would recognise her. It’d be an overseer or a manager who’d have regular contact with the stock-in-trade.”

“Presumably.”

“And he,” I went on, “gives a description to the patrol sergeants: so high, dark hair, so on and so forth. Probably a description that’d fit half the young women in Syracuse. So the chances of finding her, if she doesn’t want to be found—”

Orestes nodded. “Pity, that,” he said. “Our only possible witness.”

“And if she had seen anything,” I went on, “and if she managed to get outside the wall – if she had the sense she was born with she’d run and keep on running.” I sighed. “She must’ve got out somehow, or she’d have been found. Now we’ve got two inexplicable escapes instead of one.”

“Unless,” Orestes pointed out reasonably, “they escaped together.”

I shook my head. “A joint venture,” I said. “Co-operation in the achievement of a common purpose. I don’t think so. Naso gets drunk and fancies a quick one with the first girl he can lay his hands on. He carries her outside, they do the deed, and then they put their heads together and figure out a way of scaling the wall and evading the guards, something beyond the wit of us two distinguished scientists. And we’re sober. No, I don’t think so at all.”

Orestes nodded. “So?”

“So,” I concluded, “I don’t think Naso got out; I think he was got out by a person or persons unknown. In which case, the girl was got out too.”

“Because she was a witness?”

I shrugged. “Why not just kill her and leave her lying?” I asked. “Come to that, why disappear Naso, rather than just cut his throat and save the bother of moving the corpse over such a discouragingly formidable series of obstacles? And as for the jar of sprats—” I shook my head. “Words fail me,” I said.

Orestes grinned at me. “I think,” he said, “that Naso climbed out and took the girl with him over the wall. No, listen,” he added, as I started to object. “I can’t tell you how he might have done it, but he was a soldier, maybe he was good at silently climbing walls and evading guards. Maybe he thought it’d be a lark. Anyway, he and the girl sneak out somehow. And once he’s outside, roaming around the city, that’s when he’s killed and stuck in the jar, which happens to be the handiest hiding-place at the time.”

“Motive?”

“How about robbery?” Orestes said hopefully. “Nothing political, just everyday commercial crime. You get an honest hard-working footpad who sees this richly dressed drunk weaving his way through the Grand Portico in the middle of the night. Our footpad jumps the drunk, but the drunk’s a soldier and he fights back, so the footpad hits him a bit harder than he’d normally do and kills him. In a panic, he drags the body into a nearby warehouse and dumps it in a suitable jar.”

I was impressed. “Which reminds me,” I said. “Do we know who the jar belonged to? We know who the buyer in Rome was, but how about the seller?”

Orestes consulted his notes. “Stratocles,” he said. “General merchant.”

I nodded. “I know him,” I said. “He’s got a warehouse—” I frowned. “Address?”

Orestes looked up at me. “Just round the corner from here,” he said.

“At last.” I smiled. “Something that actually makes a bit of sense. All right,” I went on, “this robbery hypothesis of yours.”

“It fits all the known facts.”

“It covers them,” I pointed out, “like a drover’s coat. It’s not what you’d call a tailored fit.”

Orestes gave me an ‘all-right, be like that’ look. “It covers the known facts,” he said. “And it has the wonderful merit of being nothing to do with politics and diplomacy, which gets Syracuse off the hook. Also,” he added, with a rather more serious expression, “it’s the only explanation we’ve got, unless we’re prepared to entertain divine intervention.”

I stood up. “Well done,” I said. “You know, I told Hiero you’d be perfectly capable of dealing with this business on your own. But would he listen?”

“Did you really?”

“At any rate,” I said, as I walked to the open door that led to nothing at all and cautiously peered out, “it’s a working hypothesis. Of course, you’ve missed out the one thing that might just possibly prove your case.”

He looked startled. “Have I?”

I grinned and pointed at the coil of rope. “You’re sitting on it,” I said.

His eyes grew round and wide. “Of course,” he said. “Naso threw this rope into the tree!”

I picked the iron clamp off the cheese press. “Possibly using this as an improvised grappling hook.”

“And they climbed along the rope to the tree, and dropped down from the overhanging branch on to the other side of the wall.”

“Having chosen a spot, or a moment, with no guard present. Quite,” I said. “Solved your mystery for you. Of course,” I added, “you haven’t yet explained how the rope and the clamp got back in here, neatly coiled up and put away.”

“Damn,” he said. “Does that spoil my case?”

I smiled at him. “No,” I said. “It makes it interesting.”

*

The next day I thought about my king, my patron and my friend, Hiero of Syracuse, and the Romans. I also thought about war, and truth. Then I sent out for a secretary – I get cramp in my wrist these days if I write much – and dictated a report on the case. It was essentially Orestes’ theory, though I left out the rope and the cheese press, and a few other things. I fleshed it out a bit, for the benefit of any Romans who might read it (I felt sure that some would), with various observations of a scientific nature. Human strength, for example, and the limitations thereof. Agathocles, I pointed out, was a small man, past middle age. Even if he’d been able to murder a seasoned Roman soldier (by attacking him when his back was turned, for example), there was no way he could’ve disposed of the body, not without help. Such help could only have come from the domestics, since his two advisers and the remaining Romans had left the party together. As for the domestics – the cooks – they’d been thoroughly interrogated in the proper manner, were slaves, could hardly speak Greek and had never been to Agathocles’ house before. They left shortly after the guests, and they all agreed that none of them had been out of the others’ sight all evening. It was just possible that Agathocles, having murdered Naso, could have suborned them all – it would’ve had to be all of them – with bribes to help him with the body, but I left it to the common sense of the reader to conclude that it was highly unlikely. If Agathocles had wanted to kill Naso, surely he’d have laid a better plan and made sure he had his helpers in place before the event, rather than relying on recruiting slaves he’d never met before. The same, I more or less implied, held true of the servers, who were also from Syriscus’ agency. As for the flute-girls, including the one carried off by Naso, they could be ruled out straight away, since mere slips of girls wouldn’t have been capable of manhandling Naso’s substantial body. Therefore, I concluded, if Naso hadn’t been removed from the house by anybody else, he must’ve removed himself. That proposition established, the likeliest reconstruction of events, I suggeste

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...