- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

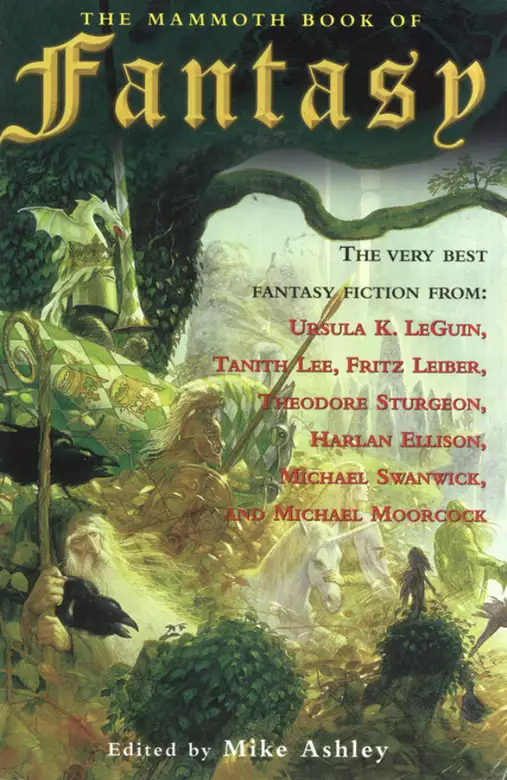

The Mammoth Book of Great Fantasy offers a wonderful collection - both classic and new - of this ever-popular genre. Mike Ashley brings together the great masters and originators of the form, such as George Macdonald and Lord Dunsany, through the great days of Conan the Barbarian, Elric and Melnibone and, of course, the creations of J.R.R.Tolkien, to today's craftsmen of fantasy such as Terry Pratchett, David Gemmell and Tanith Lee. Stories include: Yesterday was Monday, in which Theodore Sturgeon writes about a man who goes to sleep on Monday and awakes to find the next day is Wednesday - he has slipped out of time. The Wall Around the World, by Theodore Cogswell, tells of a young boy who masters flight in order to escape from a world in which he has become trapped. A Witch Shall be Born, one of Robert E.Howards greatest Conan the Barbarian stories. Aelfwine of England, a rare tale by J R R Tolkien, linking Dark Age Britain to Middle Earth.

Release date: November 28, 2013

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of Fantasy

Mike Ashley

“Nets of Silver and Gold” © 1984 by James P. Blaylock. First published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, December 1984. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Wall Around the World” © 1953 by Theodore R. Cogswell. First published in Beyond, September 1953. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“The Sunlight on the Water” © 2001 by Louise Cooper. First publication, original to this anthology. Printed by permission of the author’s estate.

“Pixel Pixies” © 1999 by Charles de Lint. First published as Pixel Pixies (chapbook) by Triskell Press. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Hoard of the Gibbelins” © 1911 by Lord Dunsany. First published in the Sketch, 25 January 1911. Reprinted by permission of the Curtis Brown Literary Agency.

“Paladin of the Lost Hour” by Harlan Ellison © 1985, 1986 by the Kilimanjaro Corporation. First published in Universe 15, edited by Terry Carr (New York: Doubleday, 1985). Reprinted by arrangement with and permission of the author and the author’s agent, Richard Curtis Associates, Inc., New York. All rights reserved.

“The Phantasma of Q———— © 1998 by Lisa Goldstein. First published in Ms Magazine, March/April 1998. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Valley of the Worm” © 1934 by Robert E. Howard. First published in Weird Tales, February 1934. Reprinted by permission of Robert E. Howard Properties, Inc.

“A Hero at the Gates” © 1979 by Tanith Lee. First published in Shayol #3, 1979 and incorporated into Cyrion (New York: DAW Books, 1982). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Darkrose and Diamond” © 1999 by Ursula K. Le Guin. First published in the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, October/November 1999. Reprinted by permission of the Virginia Kidd Agency, Inc. on behalf of the author.

“The Howling Tower” © 1941 by Fritz Leiber. First published in Unknown, June 1941 and incorporated in Two Sought Adventure (New York: Gnome Books, 1957). Reprinted by permission of Richard Curtis Associates, Inc. on behalf of the author’s estate.

“The Golden Key” by George Macdonald, first published in Dealings With the Fairies (Alexander Strahan, 1867). Copyright expired in 1956.

“Lady of the Skulls” © 1993 by Patricia A. McKillip. First published in Strange Dreams, edited by Stephen R. Donaldson (New York: Bantam Spectra, 1993). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Moon Pool” by A. Merritt, first published in All-Story Weekly, 22 June 1918. Copyright expired in 1975.

“Kings in Darkness” © 1962 by Michael Moorcock. First published in Science Fantasy, August 1962. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“King Yvorian’s Wager” © 1989 by Darrell Schweitzer. First published in Weird Tales, Winter 1989/90. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Man Who Painted the Dragon Griaule” © 1984 by Lucius Shepard. First published in the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, December 1984. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Last Hieroglyph” © 1935 by Clark Ashton Smith. First published in Weird Tales, April 1935. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate, CASiana Enterprises.

“Yesterday Was Monday” © 1941 by Theodore Sturgeon. First published in Unknown, June 1941. Reprinted by permission of The Theodore Sturgeon Literary Trust, c/o The Lotts Agency, New York.

“The Edge of the World” © 1989 by Michael Swanwick. First published in Full Spectrum 2, edited by Lou Aronica, Shawna McCarthy, Amy Stout and Pat LoBrutto (New York: Doubleday Foundation, 1989). Reprinted by permission of the Virginia Kidd Agency, Inc. on behalf of the author.

“The Sorcerer Pharesm” © 1966 by Jack Vance. First published in the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, April 1966 and incorporated in The Eyes of the Overworld (New York: Ace Books, 1966). Reprinted by permission of The Lotts Agency, New York, on behalf of the author.

“Audience” © 1997 by Jack Womack. First published in The Horns of Elfland, edited by Ellen Kushner, Donald G. Keller and Delia Sherman (New York: Roc, 1997). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Bells of Shoredan” © 1966 by Roger Zelazny. First published in Fantastic, March 1966. Reprinted by permission of the Pimlico Agency, Inc. on behalf of the author’s estate.

When I read the first of the Harry Potter books parts of it reminded me of the following story. I doubt that J. K. Rowling has read this story, so I can’t imagine it served as any inspiration, but it goes to show how great minds think alike. Except that in the case of Ted Cogswell it was over sixty years ago. Cogswell (1918–87) was an American author and academic, who was refreshingly challenging. His fiction, of which there is all too little, was always original, clever and ingenious. His best work will be found in the story collections The Wall Around the World (1962) and The Third Eye (1968).

HE WALL THAT WENT ALL THE WAY AROUND the World had always been there, so nobody paid much attention to it – except Porgie.

Porgie was going to find out what was on the other side of it – assuming there was another side – or break his neck trying. He was going on fourteen, an age that tends to view the word impossible as a meaningless term invented by adults for their own peculiar purposes. But he recognized that there were certain practical difficulties involved in scaling a glassy-smooth surface that rose over 1,000 feet straight up. That’s why he spent a lot of time watching the eagles.

This morning, as usual, he was late for school. He lost time finding a spot for his broomstick in the crowded rack in the school yard, and it was exactly six minutes after the hour as he slipped guiltily into the classroom.

For a moment, he thought he was safe. Old Mr Wickens had his back to him and was chalking a pentagram on the blackboard.

But just as Porgie started to slide into his seat, the schoolmaster turned and drawled, “I see Mr Mills has finally decided to join us.”

The class laughed, and Porgie flushed.

“What’s your excuse this time, Mr Mills?”

“I was watching an eagle,” said Porgie lamely.

“How nice for the eagle. And what was he doing that was of such great interest?”

“He was riding up on the wind. His wings weren’t flapping or anything. He was over the box canyon that runs into the east wall, where the wind hits the wall and goes up. The eagle just floated in circles, going higher all the time. You know, Mr Wickens, I’ll bet if you caught a whole bunch of eagles and tied ropes to them, they could lift you right up to the top of the wall!”

“That,” said Mr Wickens, “is possible – if you could catch the eagles. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ll continue with the lecture. When invoking Elementals of the Fifth Order, care must be taken to . . .”

Porgie glazed his eyes and began to think up ways and means to catch some eagles.

The next period, Mr Wickens gave them a problem in Practical Astrology. Porgie chewed his pencil and tried to work on it, but couldn’t concentrate. Nothing came out right – and when he found he had accidentally transposed a couple of signs of the zodiac at the very beginning, he gave up and began to draw plans for eagle traps. He tried one, decided it wouldn’t work, started another—

“Porgie!”

He jumped. Mr Wickens, instead of being in front of the class, was standing right beside him. The schoolmaster reached down, picked up the paper Porgie had been drawing on, and looked at it. Then he grabbed Porgie by the arm and jerked him from his seat.

“Go to my study!”

As Porgie went out the door, he heard Mr Wickens say, “The class is dismissed until I return!”

There was a sudden rush of large-, medium-, and small-sized boys out of the classroom. Down the corridor to the front door they pelted, and out into the bright sunshine. As they ran past Porgie, his cousin Homer skidded to a stop and accidentally on purpose jabbed an elbow into his ribs. Homer, usually called “Bull Pup” by the kids because of his squat build and pugnacious face, was a year older than Porgie and took his seniority seriously.

“Wait’ll I tell Dad about this. You’ll catch it tonight!” He gave Porgie another jab and then ran out into the schoolyard to take command of a game of Warlock.

Mr Wickens unlocked the door to his study and motioned Porgie inside. Then he shut and locked it carefully behind him. He sat down in the high-backed chair behind his desk and folded his hands.

Porgie stood silently, hanging his head, filled with that helpless guilty anger that comes from conflict with superior authority.

“What were you doing instead of your lesson?” Mr Wickens demanded.

Porgie didn’t answer.

Mr Wickens narrowed his eyes. The large hazel switch that rested on top of the bookcase beside the stuffed owl lifted lightly into the air, drifted across the room, and dropped into his hand.

“Well?” he said, tapping the switch on the desk.

“Eagle traps,” admitted Porgie. “I was drawing eagle traps. I couldn’t help it. The wall made me do it.”

“Proceed.”

Porgie hesitated for a moment. The switch tapped. Porgie burst out, “I want to see what’s on the other side! There’s no magic that will get me over, so I’ve got to find something else!”

Tap, went the switch. “Something else?”

“If a magic way was in the old books, somebody would have found it already!”

Mr Wickens rose to his feet and stabbed one bony finger accusingly at Porgie. “Doubt is the mother of damnation!”

Porgie dropped his eyes to the floor and wished he was somewhere else.

“I see doubt in you. Doubt is evil, Porgie, evil! There are ways permitted to men and ways forbidden. You stand on the brink of the fatal choice. Beware that the Black Man does not come for you as he did for your father before you. Now, bend over!”

Porgie bent. He wished he’d worn a heavier pair of pants.

“Are you ready?”

“Yes, sir,” said Porgie sadly.

Mr Wickens raised the switch over his head. Porgie waited. The switch slammed – but on the desk.

“Straighten up,” Mr Wickens said wearily. He sat down again. “I’ve tried pounding things into your head, and I’ve tried pounding things on your bottom, and one end is as insensitive as the other. Porgie, can’t you understand that you aren’t supposed to try and find out new things? The Books contain everything there is to know. Year by year, what is written in them becomes clearer to us.”

He pointed out the window at the distant towering face of the wall that went around the world. “Don’t worry about what is on the other side of that! It may be a place of angels or a place of demons – the Books do not tell us. But no man will know until he is ready for that knowledge. Our broomsticks won’t climb that high, our charms aren’t strong enough. We need more skill at magic, more understanding of the strange unseen forces that surround us. In my grandfather’s time, the best of the broomsticks wouldn’t climb over 100 feet in the air. But Adepts in the Great Tower worked and worked until now, when the clouds are low, we can ride right up among them. Some day we will be able to soar all the way to the top of the wall—”

“Why not now?” Porgie asked stubbornly. “With eagles.”

“Because we’re not ready,” Mr Wickens snapped. “Look at mind-talk. It was only thirty years ago that the proper incantations were worked out, and even now there are only a few who have the skill to talk across the miles by just thinking out their words. Time, Porgie – it’s going to take time. We were placed here to learn the Way, and everything that might divert us from the search is evil. Man can’t walk two roads at once. If he tries, he’ll split himself in half.”

“Maybe so,” said Porgie. “But birds get over the wall, and they don’t know any spells. Look, Mr Wickens, if everything is magic, how come magic won’t work on everything? Like this, for instance—”

He took a shiny quartz pebble out of his pocket and laid it on the desk.

Nudging it with his finger, he said:

Stone fly,

Rise on high,

Over cloud

And into sky.

The stone didn’t move.

“You see, sir? If words work on broomsticks, they should work on stones, too.”

Mr Wickens stared at the stone. Suddenly it quivered and jumped into the air.

“That’s different,” said Porgie. “You took hold of it with your mind. Anybody can do that with little things. What I want to know is why the words won’t work by themselves.”

“We just don’t know enough yet,” said Mr Wickens impatiently. He released the stone and it clicked on the desktop. “Every year we learn a little more. Maybe by your children’s time we’ll find the incantation that will make everything lift.” He sniffed. “What do you want to make stones fly for, anyhow? You get into enough trouble just throwing them.”

Porgie’s brow furrowed. “There’s a difference between making a thing do something, like when I lift it with my hand or mind, and putting a spell on it so it does the work by itself, like a broomstick.”

There was a long silence in the study as each thought his own thoughts.

Finally Mr Wickens said, “I don’t want to bring up the unpleasant past, Porgie, but it would be well to remember what happened to your father. His doubts came later than yours – for a while he was my most promising student – but they were just as strong.”

He opened a desk drawer, fumbled in it for a moment, and brought out a sheaf of papers yellow with age. “This is the paper that damned him: ‘An Enquiry into Non-Magical Methods of Levitation’. He wrote it to qualify for his Junior Adeptship.” He threw the paper down in front of Porgie as if the touch of it defiled his fingers.

Porgie started to pick it up.

Mr Wickens roared, “Don’t touch it! It contains blasphemy!”

Porgie snatched back his hand. He looked at the top paper and saw a neat sketch of something that looked like a bird – except that it had two sets of wings, one in front and one in back.

Mr Wickens put the papers back in the desk drawer. His disapproving eyes caught and held Porgie’s as he said, “If you want to go the way of your father, none of us can stop you.” His voice rose sternly, “But there is one who can . . . Remember the Black Man, Porgie, for his walk is terrible! There are fires in his eyes and no spell may defend you against him. When he came for your father, there was darkness at noon and a high screaming. When the sunlight came back, they were gone – and it is not good to think where.”

Mr Wickens shook his head as if overcome at the memory and pointed towards the door. “Think before you act, Porgie. Think well!”

Porgie was thinking as he left, but more about the sketch in his father’s paper than about the Black Man.

The orange crate with the two boards across it for wings had looked something like his father’s drawing, but appearances had been deceiving. Porgie sat on the back steps of his house feeling sorry for himself and alternately rubbing two tender spots on his anatomy. Though they were at opposite ends, and had different immediate causes, they both grew out of the same thing. His bottom was sore as a result of a liberal application of his uncle’s hand. His swollen nose came from an aerial crack-up.

He’d hoisted his laboriously contrived machine to the top of the woodshed and taken a flying leap in it. The expected soaring glide hadn’t materialized. Instead, there had been a sickening fall, a splintering crash, a momentary whirling of stars as his nose banged into something hard.

He wished now he hadn’t invited Bull Pup to witness his triumph, because the story’d got right back to his uncle – with the usual results.

Just to be sure the lesson was pounded home, his uncle had taken away his broomstick for a week – and just so Porgie wouldn’t sneak out, he’d put a spell on it before locking it away in the closet.

“Didn’t feel like flying, anyway,” Porgie said sulkily to himself, but the pretence wasn’t strong enough to cover up the loss. The gang was going over to Red Rocks to chase bats as soon as the sun went down, and he wanted to go along.

He shaded his eyes and looked towards the western wall as he heard a distant halloo of laughing voices. They were coming in high and fast on their broomsticks. He went back to the woodshed so they wouldn’t see him. He was glad he had when they swung low and began to circle the house yelling for him and Bull Pup. They kept hooting and shouting until Homer flew out of his bedroom window to join them.

“Porgie can’t come,” he yelled. “He got licked and Dad took his broom away from him. Come on, gang!”

With a quick looping climb, he took the lead and they went hedge-hopping off towards Red Rocks. Bull Pup had been top dog ever since he got his big stick. He’d zoom up to 500 feet, hang from his broom by his knees and then let go. Down he’d plummet, his arms spread and body arched as if he were making a swan dive – and then, when the ground wasn’t more than 100 feet away, he’d call and his broomstick would arrow down after him and slide between his legs, lifting him up in a great sweeping arc that barely cleared the treetops.

“Show-off!” muttered Porgie and shut the woodshed door on the vanishing stick-riders.

Over on the workbench sat the little model of paper and sticks that had got him into trouble in the first place. He picked it up and gave it a quick shove into the air with his hands. It dived towards the floor and then, as it picked up speed, tilted its nose towards the ceiling and made a graceful loop in the air. Levelling off, it made a sudden veer to the left and crashed against the woodshed wall. A wing splintered.

Porgie went to pick it up. Maybe what works for little things doesn’t work for big ones, he thought sourly. The orange crate and the crossed boards had been as close an approximation of the model as he had been able to make. Listlessly, he put the broken glider back on his workbench and went outside. Maybe Mr Wickens and his uncle and all the rest were right. Maybe there was only one road to follow.

He did a little thinking about it and came to a conclusion that brought forth a secret grin. He’d do it their way – but there wasn’t any reason why he couldn’t hurry things up a bit. Waiting for his grandchildren to work things out wasn’t getting him over the wall.

Tomorrow, after school, he’d start working on his new idea, and this time maybe he’d find the way.

In the kitchen, his uncle and aunt were arguing about him. Porgie paused in the hall that led to the front room and listened.

“Do you think I like to lick the kid? I’m not some kind of an ogre. It hurt me more than it hurt him.”

“I notice you were able to sit down afterwards,” said Aunt Olga dryly.

“Well, what else could I do? Mr Wickens didn’t come right out and say so, but he hinted that if Porgie didn’t stop mooning around, he might be dropped from school altogether. He’s having an unsettling effect on the other kids. Damn it, Olga, I’ve done everything for that boy I’ve done for my own son. What do you want me to do, stand back and let him end up like your brother?”

“You leave my brother out of this! No matter what Porgie does, you don’t have to beat him. He’s still only a little boy.”

There was a loud snort. “In case you’ve forgotten, dear, he had his thirteenth birthday last March. He’ll be a man pretty soon.”

“Then why don’t you have a man-to-man talk with him?”

“Haven’t I tried? You know what happens every time. He gets off with those crazy questions and ideas of his and I lose my temper and pretty soon we’re back where we started.” He threw up his hands. “I don’t know what to do with him. Maybe that fall he had this afternoon will do some good. I think he had a scare thrown into him that he won’t forget for a long time. Where’s Bull Pup?”

“Can’t you call him Homer? It’s bad enough having his friends call him by that horrible name. He went out to Red Rocks with the other kids. They’re having a bat hunt or something.”

Porgie’s uncle grunted and got up. “I don’t see why that kid can’t stay at home at night for a change. I’m going in the front room and read the paper.”

Porgie was already there, flipping the pages of his schoolbooks and looking studious. His uncle settled down in his easy chair, opened his paper, and lit his pipe. He reached out to put the charred match in the ashtray, and as usual the ashtray wasn’t there.

“Damn that woman,” he muttered to himself and raised his voice: “Porgie.”

“Yes, Uncle Veryl?”

“Bring me an ashtray from the kitchen, will you please? Your aunt has them all out there again.”

“Sure thing,” said Porgie and shut his eyes. He thought of the kitchen until a picture of it was crystal-clear in his mind. The beaten copper ashtray was sitting beside the sink where his aunt had left it after she had washed it out. He squinted the little eye inside his head, stared hard at the copper bowl, and whispered:

Ashtray fly,

Follow eye.

Simultaneously he lifted with his mind. The ashtray quivered and rose slowly into the air.

Keeping it firmly suspended, Porgie quickly visualized the kitchen door and the hallway and drifted it through.

“Porgie!” came his uncle’s angry voice.

Porgie jumped, and there was a crash in the hallway outside as the bowl was suddenly released and crashed to the floor.

“How many times have I told you not to levitate around the house? If it’s too much work to go out to the kitchen, tell me and I’ll do it myself.”

“I was just practising,” mumbled Porgie defensively.

“Well, practise outside. You’ve got the walls all scratched up from banging things against them. You know you shouldn’t fool around with telekinesis outside sight range until you’ve mastered full visualization. Now go and get me that ashtray.”

Crestfallen, Porgie went out the door into the hall. When he saw where the ashtray had fallen, he gave a silent whistle. Instead of coming down the centre of the hall, it had been 3 feet off course and heading directly for the hall table when he let it fall. In another second, it would have smashed into his aunt’s precious black alabaster vase.

“Here it is, Uncle,” he said, taking it into the front room. “I’m sorry.”

His uncle looked at his unhappy face, sighed and reached out and tousled his head affectionately.

“Buck up, Porgie. I’m sorry I had to paddle you this afternoon. It was for your own good. Your aunt and I don’t want you to get into any serious trouble. You know what folks think about machines.” He screwed up his face as if he’d said a dirty word. “Now, back to your books – we’ll forget all about what happened today. Just remember this, Porgie: if there’s anything you want to know, don’t go fooling around on your own. Come and ask me, and we’ll have a man-to-man talk.”

Porgie brightened. “There’s something I have been wondering about.”

“Yes?” said his uncle encouragingly.

“How many eagles would it take to lift a fellow high enough to see what was on the other side of the wall?”

Uncle Veryl counted to ten – very slowly.

The next day Porgie went to work on his new project. As soon as school was out, he went over to the public library and climbed upstairs to the main circulation room.

“Little boys are not allowed in this section,” the librarian said. “The children’s division is downstairs.”

“But I need a book,” protested Porgie. “A book on how to fly.”

“This section is only for adults.”

Porgie did some fast thinking. “My uncle can take books from here, can’t he?”

“I suppose so.”

“And he could send me over to get something for him, couldn’t he?”

The librarian nodded reluctantly.

Porgie prided himself on never lying. If the librarian chose to misconstrue his questions, it was her fault, not his.

“Well, then,” he said, “do you have any books on how to make things fly in the air?”

“What kind of things?”

“Things like birds.”

“Birds don’t have to be made to fly. They’re born that way.”

“I don’t mean real birds,” said Porgie. “I mean birds you make.”

“Oh, Animation. Just a second, let me visualize.” She shut her eyes and a card catalogue across the room opened and shut one drawer after another. “Ah, that might be what he’s looking for,” she murmured after a moment, and concentrated again. A large brass-bound book came flying out of the stacks and came to rest on the desk in front of her. She pulled the index card out of the pocket in the back and shoved it towards Porgie. “Sign your uncle’s name here.”

He did and then, hugging the book to his chest, got out of the library as quickly as he could.

By the time Porgie had worked three-quarters of the way through the book, he was about ready to give up in despair. It was all grown-up magic. Each set of instructions he ran into either used words he didn’t understand or called for unobtainable ingredients like powdered unicorn horns and the blood of redheaded female virgins.

He didn’t know what a virgin was – all his uncle’s encyclopedia had to say on the subject was that they were the only ones who could ride unicorns – but there was a redhead by the name of Dorothy Boggs who lived down the road a piece. He had a feeling, however, that neither she nor her family would take kindly to a request for 2 quarts of blood, so he kept on searching through the book. Almost at the very end he found a set of instructions he thought he could follow.

It took him two days to get the ingredients together. The only thing that gave him trouble was finding a toad; the rest of the stuff, though mostly nasty and odoriferous, was obtained with little difficulty. The date and exact time of the experiment was important and he surprised Mr Wickens by taking a sudden interest in his Practical Astrology course.

At last, after laborious computations, he decided everything was ready.

Late that night, he slipped out of bed, opened his bedroom door a crack, and listened. Except for the usual night noises and resonant snores from Uncle Veryl’s room, the house was silent. He shut the door carefully and got his broomstick from the closet – Uncle Veryl had relented about that week’s punishment.

Silently he drifted out through his open window and across the yard to the woodshed.

Once inside, he checked carefully to see that all the windows were covered. Then he lit a candle. He pulled a loose floorboard up and removed the book and his assembled ingredients. Quickly, he made the initial preparations.

First there was the matter of moulding the clay he had taken from the graveyard into a rough semblance of a bird. Then, after sticking several white feathers obtained from last Sunday’s chicken into each side of the figure to make wings, he anointed it with a noxious mixture he had prepared in advance.

The moon was just setting behind the wall when he began the incantation. Candlelight flickered on the pages of the old book as he slowly and carefully pronounced the difficult words.

When it came time for the business with the toad, he almost didn’t have the heart to go through with it; but he steeled himself and did what was necessary. Then, wincing, he jabbed his forefinger with a pin and slowly dropped the requisite three drops of blood down on the crude clay figure. He whispered:

Clay of graveyard,White cock’s feather,Eye of toad,Rise together!

Breathlessly he waited. He seemed to be in the middle of a circle of silence. The wind in the trees outside had stopped and there was only the sound of his own quick breathing. As the candlelight rippled, the clay figure seemed to quiver slightly as if it were hunching for flight.

Porgie bent closer, tense with anticipation. In his mind’s eye, he saw himself building a giant bird with wings powerful enough to lift him over the wall around the world. Swooping low over the schoolhouse during recess, he would wave his hands in a condescending gesture of farewell, and then as the kids hopped on their sticks and tried to follow him, he would rise higher and higher until he had passed the ceiling of their brooms and left them circling impotently below him. At last he would sweep over the wall with hundreds of feet to spare, over it and then down – down into the great unknown.

The candle flame stopped flickering and stood steady and clear. Beside it, the clay bird squatted, lifeless and motionless.

Minutes ticked by and Porgie gradually saw it for what it was – a smelly clod of dirt with a few feathers tucked in it. There were tears in his eyes as he picked up the body of the dead toad and said softly, “I’m sorry.”

When he came in from burying it, he grasped the image of the clay bird tightly in his mind and sent it swinging angrily around the shed. Feathers fluttered behind it as it flew faster and faster until in disgust he released it and let it smash into the rough boards of the wall. It crumbled into a pile of foul-smelling trash and fell to the floor. He stirred it with his toe, hurt, angry, confused.

His broken glider still stood w

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...