- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

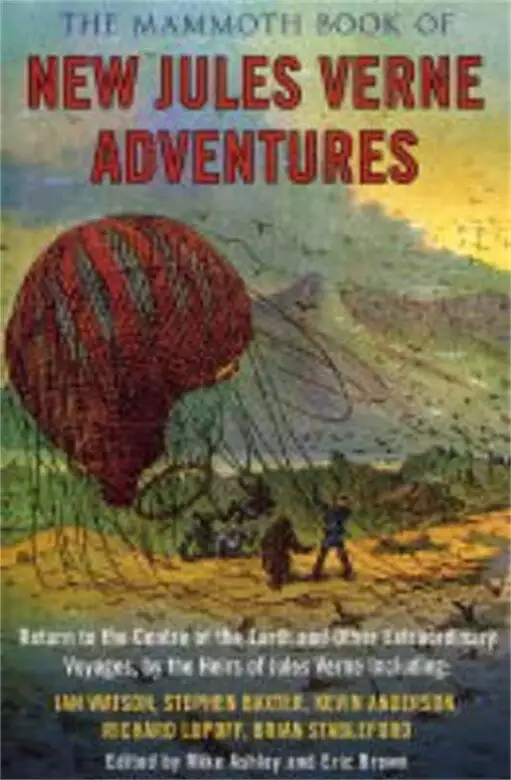

A hundred years after the death of Jules Verne, the founding father of science fiction, The Mammoth Book of New Jules Verne Adventures celebrates his amazing vision. A host of top science fiction authors pay homage to Verne's genius with a series of breathtaking stories using as a springboard his iconic ideas and characters. Collected in this anthology of Extraordinary Voyages are stories of intrigue and adventure set in the four corners of the globe, and even within it. Stories set in the past, present and future - tales that will delight with the same sense of wonder conjured by Jules Verne in such novels as Around the World in Eighty Days, Journey to the Center of the Earth and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea..

Release date: September 1, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mammoth Book of New Jules Verne Stories

Mike Ashley

In a writing life spanning over forty years, he produced more than sixty novels of adventure and exploration, creating a sub-genre of fiction that exploded on to the world at a time when both

the advances of science and technology, and the physical exploration of the world, were proceeding at an exponential rate.

Jules Verne was born in Nantes in 1828, to a prosperous middle-class family. His father was a successful lawyer who hoped that his eldest son might follow him into the profession. But Verne

dreamed of adventure. As a boy, living in the port of Nantes, he day-dreamed of sailing around the world. Family legend has it that he even stowed away aboard a ship, only to be dragged home by his

irate father when the ship docked further down the French coast. In 1848 Verne did escape – though only as far as Paris, where he combined working on the stock exchange with penning much bad

poetry and short comedy plays which were staged at the Théâtre Lyrique and the Théâtre Historique, without success or critical acclaim.

He sold a few short stories around this time, the first being “Les Premiers Navires de la marine mexicaine” (usually translated as “The Mutineers” or “A Drama in

Mexico”) which appeared in the monthly magazine Musée des familles in July 1851.

It was not until 1863, with the publication of his first book, Five Weeks in a Balloon, that success and acclaim eventually came to Verne. This is the story of Dr Fergusson, his friend

Dick Kennedy and loyal man-servant Joe Smith, and their intrepid balloon journey across the continent of Africa from Zanzibar to Senegal. Headlong adventure alternates with much (often, it must be

said, too much) scientific detail – but the story caught the imagination of readers in France, Britain and America. The novel was a best-seller, its documentary narrative convincing

some readers that it was a true account.

Verne was fortunate that his publisher, Jules Hetzel, was one of the most enterprising in France, and he saw the potential in Verne’s work. He gave Verne a contract for three books a year

and also used Verne as the final catalyst to launch his new magazine for younger readers, the Magasin d’Education et de Récréation. The first issue appeared on 20 March

1864 featuring the opening instalment of Verne’s new novel, Les Anglais au Pôle Nord (The English at the North Pole).

With a publisher keen to bring out his books, many serialized during the year and published in volume form in time for Christmas, Jules Verne’s writing career was under way. Over the

course of the next ten years he wrote the novels for which he is famous today: Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864), From the Earth to the Moon (1865), Round the Moon

(1870), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1873), Around the World in Eighty Days (1873), and The Mysterious Island (1874). These novels sold in their tens of thousands and

Verne became a wealthy man, often turning out two novels a year in a non-stop writing routine that was to last until his death in 1905.

His later books abandoned much of the scientific detail of his early novels, and he concentrated on portraying adventures set in the four corners of the globe. While these were not as popular as

his scientific romances, and sales declined towards the end of his life, his work was still in sufficient demand after his death for his publisher to bring out several volumes co-authored with (and

some wholly written by) his son Michel.

Verne is often cited today as one of the founding fathers of science fiction, along with H.G. Wells. The fact is that Verne rarely extrapolated from scientific advances to create visions of the

future – his novels were firmly grounded in the here and now of the late Victorian period. The genre Verne created had no name – though it’s as much the forerunner of the modern

techno-thriller as it was science fiction – and there were precious few other exponents: he was a craftsman who chiselled out his own niche to create stories wholly Vernian. In his better

known and most highly regarded novels, he tapped into the burgeoning scientific curiosity of the age and brought a clear-minded technological understanding to stirring stories of derring-do and

adventure in various parts of the world – as well as under the sea and in space.

Looking back, it is easy to credit Verne with greater originality than in fact he possessed. His first novel, Five Weeks in a Balloon (1863), was suggested by Edgar Allan Poe’s

“The Balloon Hoax” (1844). Another Poe story, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1837), inspired Verne to write a direct sequel, The Sphinx of the Ice-Fields

(1897). His two-part novel From the Earth to the Moon (1865) and Round the Moon (1870), were preceded by Irish author Murtagh McDermot’s Trip to the Moon (1728), whose

hero’s return from the moon is assisted by 7,000 barrels of gunpowder and a cylindrical hole dug one mile deep into the moon’s surface – a foreshadowing of Verne’s means of

firing his own characters moon-ward from the barrel of a giant gun. Verne’s Clipper of the Clouds (1886), and the sequel The Master of the World (1904), featuring a massive

propeller-driven airship The Albatross, lifted ideas from the works of the US writer Luis Senarens (Frank Reade Jnr and his Air Ship, Frank Reade Jnr in the Clouds, etc) with

whom Verne corresponded. Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864), was not the first story of subterranean adventure: the German physicist Athanasius Kircher (1601–1680) was the

author of Mundus Subterraneus, and in 1741 Ludvig Baron von Holberg published Nicolai Klimii iter Subterraneum, the story of mountaineer Klim and his adventures after falling down a

hole in the Alps and discovering a miniature subterranean solar system. Mathias Sandorf (1885) is Verne’s take on Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo (1844), while his

fascination with shipwrecked heroes can be traced back to Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and J.R. Weiss’ Swiss Family Robinson (1812): Verne even referred to his own

‘castaway’ books as Robinsonades.

However, to accuse Verne of lack of originality would be to miss the point. He was original in his genius of marrying the latest technological breakthroughs with geographical adventure, written

with a keen eye for scientific detail which convinced the reader that, no matter how far-fetched the adventure, the events portrayed were indeed possible. The first submarine had been built

and tested by Cornelius Drebble in 1620 and a submarine, the Henley, was used in the American Civil War in 1864, so Verne was hardly predicting the vessel. But his vision of a super-powered

submarine capable of travelling around the world was the inspiration that led to the first nuclear-powered submarine eventually launched in 1955 and named the USS Nautilus in deference to

Verne’s creation. It was Verne’s vision in pushing the barriers of technology and exploring the world that emerged which was a major factor in encouraging the technological revolution

that occurred in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Verne also created some of the most memorable characters in fiction. Once encountered who can forget Phileas Fogg, Captain Nemo, Impey Barbicane or the mysterious Robur, forerunners in some ways

of the later “mad scientist”. If he were alive today Verne would have been an ideal candidate for continuing the James Bond novels!

Jules Verne’s writing life encompassed much of the second half of the nineteenth century, a time of great upheaval, scientific enlightenment, and social change. His work, reflecting the

ideas and ideals of his time, has the enduring appeal of all literature written with passion and commitment. That it is still being read over a hundred years after it was written is a testament to

Verne’s ability to communicate to generation after generation of readers the wonder of adventure and exploration.

This volume, published on the centenary of Verne’s death, presents twenty-three stories in homage to the French master of adventure. Using as a starting point the works of Jules Verne, his

ideas, stories and characters and the life of the man himself, the gathered writers have produced a range of entertaining, adventurous, and thought-provoking stories. Ian Watson, for instance,

reveals the true adventures that inspired Journey to the Centre of the Earth. Mike Mallory unveils the mystery of the later life of Captain Nemo, whilst Molly Brown recounts the final

endeavour of the Baltimore Gun Club. There are further sequels to Verne’s best known books, as well as stories based on some of his lesser known novels and stories.

We’d like to think that Jules Verne would have approved.

We are all the products of our childhood and one may wonder just what events the young Jules-Gabriel Verne witnessed that later fired his imagination for his great adventure

stories. Here, as a prelude to those later adventures, Stephen Baxter takes a flight of fancy to Verne’s infancy and the dawn of the railways.

“He came to Liverpool,” the old man said to me. “The French fellow. He came here! Or at least he rode by on the embankment. He came with his father to see

the industrial wonder of the age. And not only that, though he was only a child, he saved the life of a very important man. You won’t read it in any of the history books. It was all a bit of

a scandal. But it’s true nonetheless. I’ve got proof . . .” And he produced a tin box, which he began to prise open with long, trembling fingers.

It was 1980. I was in my twenties. I had come back to my childhood home to visit family and friends.

And on a whim I had called in on old Albert Rastrick, who lived in a pretty old house called the Toll Gate Lodge, on the Liverpool road about half a mile from my parents’ home. I’d

got to know Albert ten years before when I had come knocking on his door asking questions about local history for a school project. He was a nice old guy, long widowed, and his house was full of

mementoes of family, and of the deeper history of the house itself.

But he had been born with the century, so he was eighty years old. His living room with its single window was a dark, cluttered, dusty cavern. Sitting there with a cup of lukewarm tea, watching

Albert struggle with that tin box, I was guiltily impatient to be gone.

He got the box open and produced a heap of papers, tied up with a purple ribbon. It was a manuscript, written out in a slightly wild copperplate. “A Drama on the Railway,” it was

titled, “An Autobiographical Memoir, by Lily Rastrick (Mrs.) née Ord . . .”

“Lily was my great-great-grandmother,” Albert said. “Born 1810, I believe. Produced my great-grandfather in 1832, who produced my granddad in 1851, who produced my father in

1876, who produced me. All those generations born and raised in this old house. And all that time that tin box has stayed in the family. Go on, read it,” he snapped.

I gently loosened the knot in the purple ribbon. Dust scattered from the folds, but the material, perhaps silk, was still supple. The paper was thick, creamy, obviously high quality. I lifted

the first page to see better in the light of the small window: “It was on the 15th Sept. in the year 18— that I defied the wishes of my Father and attended the opening of the

new railway. But I could scarce have imagined the adventure that would unfold for me that day!”

Albert levered himself out of his chair. “More tea?”

Lily wrote:

“I stayed the night before in Liverpool, which was never so full of strangers. All the inns in the town were crowded to overflowing, and carriages stood in the streets, for there was no

room in the stableyards.

“Thankful was I to stay in a tiny garret in the Adelphi hotel thanks to the generosity of my friend, Miss— the renowned actress, of whom I was a guest that day, and of whose company

of course my poor Father quite disapproved. It didn’t help that Father had been one of the most fervent opponents of the new railway in the first place, for he saw it as a threat to his own

livelihood – and mine, for in the future, as I was an only child, I would inherit the Toll Gate Lodge which was our home, and my Father’s source of income. How right he was! –

though, aged but twenty, I scarce saw it at the time.

“In the morning we all made to the railway yard. The engineers had assembled eight strings of carriages, with special colours to match the passengers’ tickets, and eight locomotives

to pull ’em, all steaming and panting like mighty horses. I peered at the engines, trying to pick out the bright blue flag that I knew would be borne by the famous Rocket itself.

“Of course no carriage was allowed to upstage the Prime Minister’s! It had Grecian scrolls and balustrades, and gilded pillars that maintained a canopy of rich crimson cloth. The

interior had an ottoman seat. It was like a perfect little sitting room, except that it was a peculiar oblong shape, four times as long as it was wide, and it ran on eight large iron wheels!

“At precisely ten o’clock the Prime Minister himself drove up to the yard in the Marquis of Salisbury’s carriage, drawn by four horses. He was greeted by clapping and cheering,

and a military band struck up See the Conquering Hero Comes. His train was to be pulled along by a locomotive called the Northumbrian, which was adorned by a bright lilac flag, and would be

piloted by George Stephenson himself. The train consisted of just three carriages, in the first of which would ride the military band, the second the Prime Minister himself and his guests, and the

third the railway directors and their guests – one of whom was me!

“I cannot describe my excitement as I clambered into the carriage, which was decked with silken streamers, a deep imperial purple. I admit I was callow enough to use my nail scissors to

snip off a few inches of a pretty streamer which I tied up in my hair . . .”

I fingered the bit of ribbon that had bound up Lily’s manuscript, and wondered.

I grew up in a quiet cul-de-sac in a little outer-suburb village a few miles from Liverpool city centre, on the road to Manchester. The cul-de-sac emptied out southwards into the main road.

Behind the houses ran a railway embankment. It cut straight past the northern end of the road, running dead straight west to east, paralleling the main road in its path from Liverpool to

Manchester. We kids were strictly banned from ever trying to find a way to the railway embankment, or to climb its grassy slopes. But we did know there was a disused tunnel under the embankment

behind one of the back gardens, from which, our legends had it, robbers would periodically emerge.

When I was small, steam trains still ran along the line. Great white clouds would climb into the air, and my mother would rush out to save her washing from the soot. The trains were always a

part of our lives, sweeping across the sky like low-flying planes. Their noise didn’t bother us; it was too grand to be irritating, like the weather.

As a kid you are dropped at random into time. That embankment, covered by grass and weeds, was there all my life, a great earthwork vast and unnoticed. I didn’t know we were living in the

shadow of a bit of history.

For the railway line at the bottom of my road was George Stephenson’s Liverpool & Manchester Railway, the first passenger railway in all the world. And, seven years before Queen

Victoria took the throne, Miss Lily Ord, great-great-grandmother of my old friend Albert, attended the railway’s opening – and so, maybe, did a much more famous figure.

“Soon all was ready. The Prime Minister’s train was to run on the southerly of the two parallel railroad lines, so that he might be seen from the other trains,

which would all run on the northerly line.

“At twenty minutes to eleven a cannon was fired, and off we went! Enormous masses of people lined the railroad, cheering as we went past and staring agog at such a sight as they never saw

before in their lives.

“As we left Liverpool we passed between two great rocky cliffs. Bridges had been thrown between the tops of these cliffs, and people gazed down at us, so distant they were like dolls in

the sky. I marvelled that all this was the work of man. But the hewn walls were already cloaked by mosses and ferns.

“Inside our carriage, crammed shoulder to shoulder, we talked nine to the dozen as we glided along!

“My friend Miss — the actress was a guest of Mr —, one of the railway directors, though what their relationship was I was never absolutely clear. But as the panting iron horses

gathered speed, Miss — became distressed. I was forced to exchange seats with her, so she could sit well inside the carriage.

“I found myself sitting next to a charming gentleman who introduced himself as M. Pierre Venn (or perhaps Vairn). To my surprise he was French! – he was a lawyer from the city

of Nantes. It seemed M. Venn had advised one of the railway directors regarding investment from wealthy individuals in France, many of whom have an eye on the railway for a replication in France

itself, depending of course on its success. I admit I was surprised to learn that Frenchie money had been used to build an English railway, even so many years after the downfall of Napoleon! But

Money has always been ignorant of national rivalries.

“M. Venn was with another Frenchman, a dark, rather sullen man whom M. Venn introduced as a M. Gyger, but this gentleman had not a word to say to me, or anybody else – quite unlike

the voluble Frenchie one expects. He did little but glare about rather resentfully and I quickly forgot him. (Of course I remember him well now! – but I run ahead of myself.)

“M. Venn was also accompanied by his pretty wife, and their child, their first-born, a little boy of two or three they called Julie, and they were much more fun. That scamp of a boy was

decked out in a pretty sailor’s costume, for Nantes is evidently near the coast, and the child was already obsessed by the sea and all things nautical. But he had also discovered a new

passion for Mr Stephenson’s railway; I am not sure how he managed it, but even before we set off he was already a bundle of soot, which got all over our clothes and hands! The little boy

laughed so much, his joy at the experience of the journey almost hysterical, that I think all forgave him.

“M. Venn offered me some profound thoughts on the meaning of the marvellous experience we were sharing. ‘Never has the dominion of mind more fully exhibited its sovereignty over the

world of matter than today,’ he said, ‘and in a manner which will surely beneficially influence the future destinies of mankind throughout the civilized worlds.’ And so forth!

“However as well as his interest in the Future of Man M. Venn also seemed intrigued by the Presence of Woman. He complimented me on my accent, which he said sounded Scotch, and the

rosewater scent I wore, and the purple ribbon in my hair, before moving on to the colour of my cheeks and the suppleness of my neck. That is the way of the Frenchie, I suppose. Or it may be that

Mme. Venn did not understand English.

“It wasn’t long before we emerged from deep beneath the ground to fly far above it. Over a high embankment we bowled along, looking down at the tree tops and drinking in the fresh

autumn air . . .”

Somewhere among those trees was the site of my future home. And perhaps Lily was able to make out the line of the toll road from which her father made his living.

The history of my home village has been determined by the fact that it lies on a straight line drawn between the centre of Manchester and the Liverpool docks. As the Manchester cotton trade grew

and the port of Liverpool began to expand, it was an obvious place through which to build a road.

A hundred years before George Stephenson, a consortium of Liverpool merchants petitioned for an act to set up a turnpike road, the first in Lancashire or Yorkshire save for the London trunk

routes. They installed one of their gatekeepers at the Toll Gate Lodge, where my old friend Albert was born, and indeed died. The turnpikes were a smart social invention; by making those with the

strongest vested interest in the roads, the users, pay for their upkeep, the British road system was massively and rapidly improved.

The new road was a huge success, and it galvanised the local economy. But by the early 1800s the thirty miles separating Liverpool and Manchester, by now two engines of the Industrial

Revolution, were traversed daily by hundreds of jostling horses, wagons and stagecoaches. So the local land agents and merchants began to conceive of schemes for a railway. They were fortunate

enough, or wise, to choose George Stephenson as their chief engineer. The success of the railway was a calamity for the toll road, though, and the gatekeepers who made a living from it;

Lily’s father had been right.

The geographical logic endured. In my lifetime yet another transport link, a motorway, was built through the same area. So within fifty yards or so of my front door there were marvels of

transport engineering from the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The trains stopped repeatedly, so that the notables could admire views of cuttings and viaducts and countryside, and lesser people could admire the notables. At one stop, twenty-year-old Lily

managed to talk her way into a ride on the footplate of the Northumbrian with George Stephenson himself.

“I was introduced to the little engine which carried us all along the rails. She (for they call all their curious fire-horses mares) goes on two wheels, alike to her

feet, which are driven by bright steel legs called pistons, which are propelled by steam. All this apparatus is controlled by a small steel handle, which applies or withdraws the steam from the

pistons. It is so simple an affair a child could manage it.

“The engine was able to fly at more than thirty miles an hour. But the motion was as smooth as you can imagine, and I took my bonnet off, and let the air take my hair. Behind the belching

little she-dragon which Mr Stephenson controlled with a touch, I felt not the slightest fear.”

I envied Lily; it must have been the ride of a lifetime.

“Mr Stephenson himself is a master of marvels with whom I fell awfully in love. He is a tall man, more powerfully built than one of his engines, with a shock of white hair. He is perhaps

fifty-five.” (Actually Stephenson was forty-nine.) “His face is fine, but careworn. He expresses himself with clarity and forcefulness, and although he bears the accent of his

north-east birthplace there is no coarseness or vulgarity about him at all. He told me he is the son of a colliery fireman. He learned his mechanicking working on fire engines down the mines. He

was nineteen before he could read or write, and his quest to build his railway was frustrated by the linguistic contortions of the ‘Parliament Men’ who had opposed him. But this was the

day of his triumph.”

Stephenson built his railway, all thirty miles of it, in just four years. It was a mighty undertaking, with cuttings and viaducts engineered by armies of navvies. Stephenson had to build over

sixty bridges, including the one behind my neighbour’s back garden. My embankment was three miles long, forty-five feet high and amounted to half a million cubic yards of spoil removed from

cuttings miles away.

“The train passed over a very fine viaduct, and we looked down to see the graceful legs of his mighty bridge striding across a beautiful little valley. I heard a gruff voice which could

only have been the Prime Minister’s, emanating from the carriages behind, as he called the spectacle, ‘Stupendous!’ and ‘Magnificent!’ – for so it was.

“But, it is a strange thing for a man who had proven himself so brave, I thought the Prime Minister didn’t much enjoy the ride. He said that he could not believe sensible people

would ever allow themselves to be hurled along at such speeds! And later I heard him say that if Mr Stephenson’s railway caught on, it would ‘only encourage the lower classes to travel

about.’ A good thing too I say! . . .”

Near a station called Parkside, Stephenson again halted the Northumbrian. And it was during this brief stop, as Lily wrote in her girlish hand, “that calamity struck.”

“I returned to my carriage, where I comforted my friend Miss —, who became a little less queasy now that she could hear the birds sing again. Everybody started to

get out of the carriage to taste the air and stretch his legs.

“Now, you must remember that we were travelling from Liverpool to Manchester, that is west to east, and that the Prime Minister’s train was on the southerly of the two parallel rail

lines. So the safest place to alight from our carriage was to our right, for to go left would be to step on to the other track which, though it was clear at the moment, was surely not guaranteed to

remain so! Thus M. Venn and his wife alighted safely to the right, M. Venn carrying little Julie on his shoulder. Miss — and I followed.

“But to my surprise M. Gyger, M. Venn’s sullen and uncommunicative companion, got out to the left.

“The carriages were quite open and no obstruction to vision, and I could clearly see M. Gyger walk up and down the northern track. He was joined by various lords, counts, bishops and other

worthies. I recognized only one of them, a portly man with a damaged arm and gammy leg. This was William Huskisson, Member of Parliament, who had been on hand to welcome the Prime Minister into

Liverpool that morning.

“Both parties, on both sides of the carriage, were drawn as if magnetised to the middle coach of the three, which was the Prime Minister’s. I could see him clearly, that noble nose,

the upright bearing of a soldier! I fancy the heavy drapery around his carriage rather baffled his hearing – for if not I imagine what transpired next might have been quite different.

“Since I must describe the death of a Human Being I will take care to relate what happened in sequence.

“As I walked with the Venns, I saw that M. Gyger prompted Mr Huskisson to call to the Prime Minister, ‘Oh, do step down, sir, if only for a minute! The gleam of the rail, the

billowing of the steam – quite the spectacle, sir!’ And so on. I fancy the Prime Minister would rather have stayed in the comfort of his carriage. But duty called, and he got up rather

stiffly and prepared to descend towards Gyger and Huskisson – that is, on to the northern rail.

“As he did so M. Gyger’s face assumed a most curious expression. I saw it once when my father caught a rascal who habitually skipped around our toll gate: an expression that said,

‘Got you at last, my lad!’ And I saw M. Gyger step back, quite deliberately, away from the rail, leaving Mr Huskisson standing there to assist the Prime Minister to the ground.

As I say I saw all this quite clearly, but I did not understand it at the time.

“Suddenly I was disturbed by a loud but distorted yell: ‘Get in! Get in!’

“I looked down the track, back towards Liverpool, and saw to my horror that a second train was racing down the northern line towards us. The sky-blue flag it carried told me that the

locomotive was none other than the Rocket, Stephenson’s famous victor of the Rainhill trials. That cry came from the engineer who hailed us with a speaking-trumpet, even as he struggled to

apply his brakes. Though the Venns and I were quite safe, those who foolishly wandered over the northern track were in grave danger.

“And the Prime Minister himself, his hearing perhaps baffled by the drapery, was about to step down into the Rocket’s path! All this I saw in a second, and then a great fear clamped

down on me and I was unable to move.

“Fortunately M. Venn was more courageous than I. With a muttered ‘Parbleu!’ he stepped forward – but though we were only feet from the carriage, it was too far for

him to have reached the Prime Minister in time. So M. Venn, thinking fast, called out: ‘Wellesley!’

“The Prime Minister turned at the sound of his name. And M. Venn threw his small son through the air, into the carriage and straight at the Prime Minister!

“Though he nearly lost his own balance the Prime Minister twisted and neatly caught the boy in his great hands, thus saving the child from a painful fall: the Prime Minister had the

reactions of a soldier, despite his age, and an instinct for the safety of others. With the boy in his arms he stumbled backwards into his ottoman – but he remained safely in the

carriage.

“And then the Rocket reached our train. I distinctly heard the Prime Minister call out, ‘Huskisson, for God’s sake get to your place!’ But it was too late.

“Everybody else had scrambled out of the way, off the track or behind the coaches – everybody but poor Huskisson, who, hampered by a bad leg and general portliness, fell back on to

the track. The Rocket ran over Huskisson’s leg. I heard a dreadful crunch of bone.

“When the train had passed others rushed to help him. George Stephenson quickly took command. One man began to tie his belt around the damaged leg, which pumped blood. Soon the patient

would be loaded aboard a single carriage behind the Northumbrian,

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...