- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

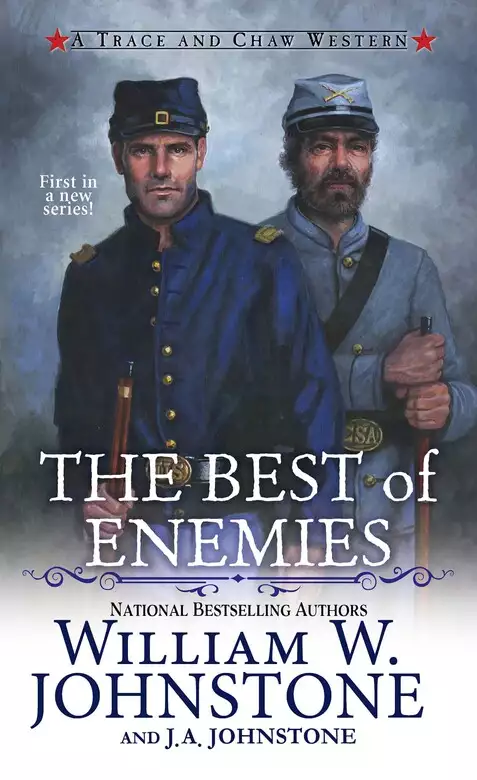

Introducing Trace and Chaw: a pugnacious pair of Civil War veterans who nearly killed each other in battle—but lived to fight another day. Together . . . .

They met in a bloodbath. Two demons in uniform caught in the middle of one hell of a war. Private Chaw, the Rebel, liked chewing tobacco and fighting blue-bellied Yanks. Private Trace, the Yankee, hated Southerners, especially ornery cusses like Chaw. But when the smoke cleared after the Battle of Deadeye Gap, the Blue and the Gray of their uniforms didn’t matter anymore. Both were stained blood red. And both were the last men standing . . .

This was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Now that the war’s over, Trace and Chaw travel the West together, taking on odd jobs. They’re handy with six-guns and gut-shredders, fond of women and liquor, and always ready to raise hell. Somehow, the unlikely partnership works—until Trace and Chaw sign up with a freighting company run by a beautiful woman. Her company is caught in the crossfire of two rival mine owners who want to control the freight routes. Like it or not, Trace and Chaw are stuck in the middle of another war. And this one’s going to be every bit as bloody—and maybe their last. . . .

Release date: August 26, 2025

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Best of Enemies

William W. Johnstone

The next thing he noticed was yet more heat, but this time it came from within himself, from below himself, as if from the earth on which he lay.

He forced his eyes open, just a crack at first; all he could see were stinging pinpricks of light through a gauze of pink that edged out to redness. Jagged, brittle snatches of memory drizzled back to him at the same time. And not a bit of it impressed him.

All this told him was that he had to be dead, given what he was recalling. He almost wished he had lost his ability to recall anything, so awful were the bits of memory of what he had seen and lived through. Or had he?

Then sound flooded in and became more pronounced. But at first, all he could hear was a whooshing and thudding.

With more effort than he’d bet he’d expended on anything in ages, the man lifted his head. It wobbled on its feeble stalk of a neck. He cracked his right eye wider than its slit and saw bright, warm light and little else. How on earth did he get here? And where was here?

All he could recall was fighting. Seemed that was all he’d done since he was born. What did that mean?

Notions, facts—or perhaps they were fabrications, he could not yet tell—flitted in and out of his mind. He gritted his teeth and fought to keep his eyes open. There, he looked down along the length of his body and saw himself, stretched out on his back in the sun. His clothes looked sodden—must be sweat, he thought.

And then, as if someone had clapped their hands to awaken him fully, he remembered who he was. And from that revelation, it was a short jump to how he got here. Wherever here was. He figured that in time, that, too, would come.

And then he remembered—the war. The war and the cursed Yankees who started it. And there he was, all laid out, baking in the sun, not certain how alive he was, or if he was on his way out. The latter possibility seemed the most likely, given the pain he felt, the light burning away at him, and the rush of memories flooding into his mind.

But right then, he figured he knew who he was, and that was pretty good. He was Chaw Dagworth, private in the army of the Confederate States of America.

He glanced down at himself again as he struggled to raise himself up onto an elbow. And if he was in the Confederate Army, then that meant his uniform would be gray. And if that was the case, why was it so sodden-looking? Ah yes, the fighting. The cursed, fool big War Twixt the States, a protracted fracas, as his old colonel used to say, caused by Yankee bellicosity.

Chaw grunted and felt a stinging in various parts of his body that quickly gave way to lancing pains, as if someone were sliding knives in and out of his arms, his sides, his legs. What was happening? And then he knew that he wasn’t seeing a sweaty uniform, he was seeing a blood-soaked uniform. And as soon as that dawned on him, the rest of his situation became as clear to him as a cool mountain stream.

As he shoved himself up, despite the constant throbbing all over his body, more memories came gushing on in. Uninvited, but there they were anyway.…

His company had been taking a ridge, below which was a hollow—what was it called? Deadeye Gap, that’s it. And then he’d seen a bluebelly and had taken off after him. That’s right, that bluebelly and Chaw got into it pretty good. For a Yankee, the man was brute enough. Must have had Rebel bark somewhere in the woodpile.

In fact, Chaw recalled shouting that at the man as they tore into each other, each giving as good as they got. That comment sure got the bluebelly riled. That foul Yankee had called Chaw a slave trader and a child killer and all manner of raw names, none of which was true. Chaw found this humorous, considering the Yank was a foul traitor and a child killer and a secret slaver himself!

Of course, Chaw had no way of verifying such, but he didn’t doubt the bluebelly was guilty of that and a whole lot more. He was a foul Yankee, after all, wasn’t he? That alone was reason enough to pin the entire mess on him.

As he lay there, Chaw pulled in as much of a breath as he could—it wasn’t a deep one nor was it clear. Sounded to him as if he was breathing through a ragged pig’s bladder. That reminded him of pig killin’ time, when the menfolk back home used to inflate and tie off the bladders for the kiddies to bat around.

None of that mattered much now. He was likely dying, and would as likely never see his poor old family ever again. Not Ma, nor Pa, nor Jube, nor dear old Daisy the hound.

Chaw grunted and slowly swung his gaze over to his left. What he saw somehow did not surprise him, although it should have. But he reckoned some part of him knew what he would see before he looked there. And what he saw did not fill him with satisfaction, as he had expected it should. Nope, seeing that dead Yank not but a few yards to his left only made Chaw Dagworth feel almighty awful.

Even if the man was a foul Yankee, that carcass left Chaw hollowed out inside, even more than before. Because it only meant that, as bad as he felt, that Yank was worse off. For he was already dead.

And so that meant that Chaw had given away his own life, and for a cause that had become so muddied and confused for him and most of his fellow Rebs, most had, at one time or another, considered running off in the night. Even though it meant risking getting shot in the back. And now, here he was, surely about to die himself, and that was a raw, hard thing to take.

The Yank, in Chaw’s brief glimpse of the man, and then on repeated forced looks, appeared to be in particularly rough condition. The bluebelly, too, was sprawled out on his back, and he, too, was covered with what looked to be a whole lot of dried blood from gashes and rents in his once-blue uniform. He knew this because there were a few spots of blue wool still visible through the darkened blood.

Was this it, then? Nothing more than kill or be killed? How on earth, he wondered, would his death, or the death of that foul Yank beside him, be helpful to the cause of the South, or for the cursed North for that matter?

Chaw closed his eyes for a moment and worked to breathe a bit more. And he came to the conclusion that there wasn’t a single scrap of usefulness in his sacrificing himself for the dang cause. No sir.

And then he heard a sound. From his left.

Chaw grunted and worked to angle his gaze back over in that direction. He blinked hard and opened his eyes again, forcing them wide. Couldn’t be. He could swear he saw that foul Yank move!

Long before he opened his eyes, Private Fullcup Trace, of the Union Army, lay awake. Keeping his eyes closed on waking each morning was a lifelong habit, and something that, even in the much-abused state he knew his body to be in, he nonetheless maintained.

He found it beneficial to slowly, over the course of several minutes, allow himself to come around to full consciousness. In this way he could take account of who he was, what had happened to him, and where he was at that moment.

All of this came to him as he lay there, sipping air between parted lips. He knew who he was—Trace, he was called—for he became aware of such as if someone had whispered it to his mind.

But it also soon became obvious to him that his normal method of waking was not going to work this day. For memory reminded him in the harshest way just what it was that had landed him where he was, and in the state he suspected his body of being in.

First, he felt a thudding building within him. It started down low, deep in his guts, and rose as if it were marching right into his chest and on up his gullet. By the time it wormed its way into his mouth and nose, he had begun to ache all over.

And then the memory of the events leading up to all of this flooded into his mind. The lashing agonies that came with what surely were a thousand cuts, stabs, cracked ribs, broken fingers, and more thrummed with a sudden and searing pain all over his body. As bad as was that pain, it bowed down before the thudding of the cannonade playing out betwixt his ears.

With more effort than he felt capable of, Trace cracked open his eyes. The sunlight that had been there, awaiting this moment with supreme impatience, drove forward and inward. As Trace squeezed his eyes shut once more, although too late to avoid this fresh, raw wash of pain, it felt as if forge-fired daggers were jamming themselves like steel vipers into his skull.

An unbidden moan, low and fragile, was accompanied with a deluge of memories that flooded over him. And he knew without doubt where he was. The battle atop that cursed ridge above Deadeye Gap, it was called. They’d found that wily Reb company they’d been chasing for weeks.

Those foolish graybacks fought like cornered lions, with claws out and fangs slashing and with a hard pistoning of their gunfire that seemed not to let up. Trace recalled wondering out loud, with some of the other Union men, if maybe the Rebel soldiers truly didn’t know that the war was all but over for them.

No, there hadn’t been any surrender as such, at least not yet. But it was bound to happen soon. That was what they had all thought going into the latest fracas with the elusive, dastardly Rebs. The enemy numbers were raggedy and slowly dwindling, but they nonetheless fought at every turn as if they were freshly minted men.

Trace groaned again as the rest of the preceding events came back to him. He recalled how he had made his way down past the far side of the battle, chasing after a pair of Reb snipers. He knew from experience that they’d been looking to sneak up around to where the Northern Army was encamped. That would not stand.

Trace had gotten the drop on them, sure, but instead of letting him take them as his prisoners, they’d put up a fight. He’d expected that, anyway. He didn’t recommend it to anyone, even a foul Rebel, but he could hardly blame them, now, could he?

As he fought, trading shots with the two snipers, Trace realized from the sounds of the battle above and behind him, atop that ridge, that the melee was not about to end in favor of these maddening Rebels and the rest of their Southern ilk.

He was all but through with these two, having pinned them pretty well, despite being a lone soldier against two men. He had the landscape to thank in part for that, too. He had been able to position himself behind a boulder the size of a wagon, while the two Rebs he’d been pursuing had found themselves at the bottom of a gully with nothing but knee-high rocks and crusty pines no thicker around than a man’s arm.

Then he had touched finger to trigger and been about ready to send those two Rebel curs barking to the netherworld. Despite how he felt about them and their cause, there was that flicker of a moment when he regretted ever being involved in this foul mess to begin with.

It had less, far less, to do with the individual soldiers, no matter the side, than it had to do with the cause each side fought for. And for all that, he knew that all these deaths could be laid at the feet of the leaders on both sides for their failure to keep talking, keep shouting at one another across the back-room negotiation tables.

Trace didn’t care how angry they got or how many days or weeks or months or years it would take. All of it would have been breath and time well spent if it had saved a single life of one of the soldiers on either side. Instead, they had ended up fighting, either by choice or, as had proved the case, by force, to fight and die for their respective so-called causes.

And Trace knew he wasn’t the only man in the Union Army who felt that way. And he had it on good authority that most Rebs felt the same darned way, too. Much good it had done any of them.

All of that flooded into and out of his mind in that whisper of a moment before he squeezed the trigger to take yet another Rebel man’s life. And at that moment, a shot whipped by his head from behind him. It spun Trace’s gaze hard over his right shoulder. At the same time, instinct drove him down to one knee.

There he spied yet another grayback. This one, however, wasn’t oblivious like his fellow soldiers. Trace had, after all, gotten the upper hand on those two Rebs down in their gully, looking this way and that.

In recalling that day, however many days before, Trace now realized that moment could well have ended it all, and in eyeblink speed. But for some reason, that crazed Rebel he’d seen over his shoulder, with his rifle aimed right at Trace’s head, had decided not to shoot him.

What he did instead genuinely surprised Trace. The man had delivered that shot at him. And when he faced him, Trace saw that the Reb hadn’t been far enough away to have missed him. Why hadn’t I heard the rascal sneaking on up behind me? thought Trace.

As if in answer to the question echoing in Trace’s skull, the Reb who’d shot at him from behind, and who held a revolver aimed right at him—he must have used his rifle to deliver that first, too-close-to-have-missed shot—shouted from about sixty feet away.

The Reb eyed him down the short barrel and barked, “I am a son of the South and as such I am too proud to shoot a man in the back, even if he is a foul, yellow, blue-bellied Yankee!”

By then, of course, Trace had his own gun aimed right at that Rebel’s gut. He rose once more to a standing position. Behind and below the big boulder, he heard a voice shout to another, “Let’s git gone back to the fight! That Yank’s done for!”

That told Trace he didn’t have much to worry about from those two. He could concentrate on dealing with this crazy Rebel. A man who had him dead to rights, but who made him turn to face him before he would shoot him was a crazy man. Or a man with a conscience.

Make that a Rebel with a conscience. He knew there were a good many of them because he’d learned a whole lot since he started in on this war, with all its marches and lousy, maggoty food, and surly officers and lack of leadership with brains.

He’d learned that most Rebs were just about the same as most Yanks. That was to say, they were all just men. Men with wives and children and parents and cousins and friends and homes and farms, all of it.

And now here was one who wanted to fight him, face-to-face, fair and square. All right, then, thought Trace. Let’s get to it.

He rose back to standing height, keeping his rifle aimed at that man’s chest, and said, “What’s it going to be, Reb? We have each other square on!”

“Shut up and approach. We’ll see how far you make it, you stinking Yank!”

And so they had advanced on each other, slow step by slow step, their respective barrels not faltering, their boot steps sure and well placed, their eyes never leaving the other’s, their trigger fingers ready to dole out the last sound the other man would ever hear.

But neither man pulled a trigger. Neither man dared to be the first, apparently, for they each advanced and strode with caution and unwavering concentration right toward the other.

And then they were close enough to see the grime caked in the lines on their faces, to see that they each could use a real shave, a haircut, a month’s worth of sleep, and the same of food.

“Enough!” growled Fullcup Trace, flinging away his rifle. He didn’t care any longer.

They’d been staring each other down for long, long minutes, slowly circling, and the situation had grown more than tiresome. A vital need had grown in him that they fight like men, men who were unafraid to cower behind the false cowardice of a gun.

As Trace regarded the other man, the grayback sneered, and he, too, sent his own gun spinning to the dirt. That was when things really began to head off into an interesting direction.

Again, as if by mutual unspoken agreement, the two men both sneered, their lips pulled back over tight-set teeth. Their eyes narrowed and growls crawled up out of their throats.

Arms drew up fast and their hands sought each other with clawlike fingers, fingers that closed on the other, on arms and chests. They balled wool tunics and at the same time jerked the other man this way and that, hoping to gain the upper hand.

They each gave voice to a deep rage that, while directed at the other man, really represented the anguish and frustration and fear and confusion they had each felt for the past couple of years at being forced to kill or be killed.

Propelled by a clot of such feelings fueling their rage, the two men grabbed onto each other hard and fast, neither uttering any sounds that could be recognized as words. Instead, they were growls and barks and the utterances of seething anger.

They circled, breaking their holds, only to collide again, one arm grasping clothing or hair, it mattered not. The other was curled into a thick fist that drew back, then drove forward, like a sledge wielded by a railway man.

Their blows staggered each other, sent blasts of starlight even during the day before the receiver’s sweat-riddled eyes. The punches and cudgel-like shots staggered each other, and yet neither man relented. Once they had agreed to brawl it out, neither man gave the other a moment’s peace. Legs kicked, circled around other legs, seeking to trip.

Once, the Reb was able to use his momentum to drive the Yank backward. One of the man’s blue-clad legs lay pinned beneath him, and the Reb knew something had happened to that bent knee. It had not broken, for the man would have yipped like a kicked dog, but nonetheless he knew something very painful had overtaken the man.

He grinned, his gritted teeth stained yellow and gray, as if to match his uniform, and he used the moment’s pain to his advantage, jamming his own knee into the Yank’s middle.

But his hubris at finding himself atop the other was short-lived, for he had lost, for a moment, his accounting of the Yank’s left arm. And as the Reb bent low to deliver a pulled-back punch, he left his own right side exposed.

The desperate Yank’s left fist slammed into the right side of the Reb’s ribs with the force of a hickory log being jammed, butt end first, into the man’s torso, with deadly, unexpected momentum.

The blow shoved any air the Reb had in his chest up and out in a rush that ended in a wheeze. The worst of it for the Reb was feeling the sickening, sharp, lancing pain deep inside. He’d been down that painful road before and knew he’d just received a broken rib or three from that foul Yank.

The Reb collapsed to his left, falling off the pinned Yank long enough that the man in blue could also roll to his left. Again, as if by mutual consent, the two men rose to their knees, facing each other, panting their rasping breaths. Hatred, directed at each other, glowed through their narrowed eyes, their chests working like bellows.

The Yank put little weight on his bum knee, for it pained him already and he knew it was swelling. He bet that something inside, the stringy bits in a man’s body that hold flesh to bone, had torn or separated somehow.

The Reb raised his left hand to rest it against the right side of his ribs. He knew it showed a weakness, a wound dealt by the Yank, but he had to do it. Trace probed gingerly and again could not help the sharp-drawn breath of limping forward. With the Reb sipping shallow breaths, they each drove at the other. Now each was intent at furthering the damage he had already inflicted on the other man.

How long they fought, neither man knew. Not that either of them cared. The brawl had become far more than two enemies having it out to some sort of end. It was the long-pent result of years of hardship shoved on them every day by their superiors, by the weather, by other soldiers, by bad food and worse water, by unforgiving terrain, and by the long-forgotten reasons behind why each was told they must kill other men.

And so it went, for hours or days or weeks, neither man knew nor cared. At some point, one of them—neither could recall later which—tugged free his knife barely an eyeblink’s worth of time before the other did.

Thus the fight went on, continuing with each man guessing the move of the other, growl for growl, punch for punch, kick for kick, driving knee for driving knee, butting head for butting head, lunging, snapping teeth for the same. And now was the deadly promise of honed steel.

The appearance of blades in their scar-knuckled, brawl-reddened hands kindled in each man a renewed fire, a burning rage to kill and to not be killed. It was no surprise to either man that his opponent wore a sheath knife on his belt. Most soldiers did, and frequently these tools were brought from home, cherished items that a man regarded with as much or more fondness than his gun.

A hip knife was perhaps a man’s most-relied-upon possession. It was a tool he used many times a day. Men shaved with them, used them to cut hair and trim beards, to skin, gut, and slice fresh-killed critters for the fry pan or pot, from turtles to swamp rats to rabbits and more.

A big-bladed knife also could be used to split lengths of branch wood for kindling, for sharpening sticks, for cooking and hewing stakes for tents. And as long as a man had a whetstone in his possibles sack, it could also be used to dig a cat hole in the steel-dulling earth, should a man care that much about covering his leavings with more than forest duff.

Occasionally, although the men agreed it was happening more and more as the war dragged on, these knives had begun to be used to defend one’s life, and to attack a foe as well.

As each man, Trace and Chaw, lifted free his knife, a sneer rose unbidden on their faces. Without warning, they rushed at each other, snarls of rage ripping from their mouths.

They fought with bedraggled bodies sporting bloodshot eyes, bruised and bloodied mouths from split lips and smacked noses, and sweat-plastered hair. They wore the grime of repeated slamming and rolling in the dust and churned soil of the small, scree-riddled plateau they each had been stomping and trampling and kicking and furrowing for hours.

They fought as beasts, coming together amidst howls and clouds of dust, slashing and driving, peeling apart and wielding keen blades afresh with each parry and thrust. Over and over they attacked, not seeming to lose the renewed, whetted appetite for blood they shared.

Their thirst for killing clouded their usual individual sensibilities and they fought hard and viciously. They rarely fell apart without leaving hacked slices in the arms of woolen tunics, on through into the sweat-soaked, longhandle underwear beneath, finally drawing blood in scarred skin befouled by war and hard living.

Cuts more than gashes, although there were plenty of those as well, covered each man’s head, face, torso, arms, hips, backsides, and calves. It seemed to each man as if they were covered with the denizens of a huge hive of deadly hornets, for with every move they made, their bodies screamed from the constant, stinging pain of a thousand lacerations.

Over time—neither man knew how much—the welter of agony each found himself mired within began to take its due toll.

Each man, the Reb and the Yank, after hours of cutting and slashing, howling and colliding, clubbing and flailing at the other, hammer and tongs, staggered backward.

Trace, the Yank, had no idea how he had managed to stay upright for so very long as his knee had somehow endured far beyond ordinary pain.

When he had been able to steal a quick glance at himself, he had been shocked to see, through the slashed fabric of his trousers, that they were no longer showing any trace of blue. They were matted with a reddened black, and were sodden with sweat and blood. His own and that of the foul, determined Reb.

What had shocked him most was the size of his knee. It had swelled to what seemed the size of a man’s head. The ragged trouser leg about it, although slashed, had also brought with it a cold dose of luck. The knee had been able to swell and not be constricted by the fabric itself, for good or ill.

The Reb, leaning against the boulder before which the Yank had begun the fight, felt his breath wheezing in and out of his damaged breadbasket and rib cage. He hated to admit it, but that Yank had delivered into his side one mighty wallop, a pummeling such that the Reb was certain he might never again breathe as a normal man.

That thought had been from who knew how long before. Before the brutality their knives had inflicted. Now the Reb was a gasping, wheezing mess.

It was all he could do, now that they had fallen back apart from each other once again, to maintain his tender hold on his knife. He glanced down at himself and saw nothing he recognized.

Not his right hand, nor the knife in its grasp. He knew there was a knife there somewhere, hidden under a thick, syrupy coating of red-black gore that streamed and sluiced in steady rivulets down his drooped arm. The hand and fingers were covered with their own slick gore, beneath which dozens of cuts screamed at once. As did his entire body.

Chaw glanced up once more, as he held his left hand to his right-side rib cage, the tenderest spot on his entire savaged form. “If I … look …”

He swallowed and licked his lips, his voice a cracked, croaking thing. My, how he longed for a long sip of cool, clear water. “If I looked as bad … as you … Yank … I’d up and die already.”

The Yank regarded the Reb while he leaned against the trunk of a much-scuffed pine. What he wanted to say was, Of course you would! You’re a weak-kneed Rebel! But what came out, between huffing gasps was, “Could say the same … to you, Reb.…”

In all the time of that fight, neither man had not uttered much more than grunts and shouts, sounds that were not words. Though they did not much care. But now, hearing their voices, after hearing nothing but raw animal sounds from themselves, they surprised each of them.

It also seemed to trigger something within each of them once more, yet another animalistic lunge to satisfy the unreasoning rage each felt at nearly being killed by the other.

They bolted forward, once more as if they had nodded in agreement with each other, and yet they hadn’t. This did not slow them down, but the wearing, atrophying pain of the protracted battle had shown its strain as each man shoved up and away from the only things that were really keeping them upright—the boulder and the tree.

They lurched forward, staggering and eyeing each other through blood-flecked eyelashes, blinking and wheezing, their knives held halfway up in weak grasps. Each man with his eyes fixed on the other advanced. Paltry, feeble step by lurching, halting step, they drew closer, slowly, grunting and wheezing, bleeding and groaning.

And, as had happened since they began their attempt at mutual destruction, they each faltered within ten feet of each other, and the last thing each man saw was the other, his sworn mortal foe, sagging and collapsing. Eyes rolled back in heads, knees buckled, heads slopped backward on their weak stalks as their bodies slowly sank to the churned, bloodied earth. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...