- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

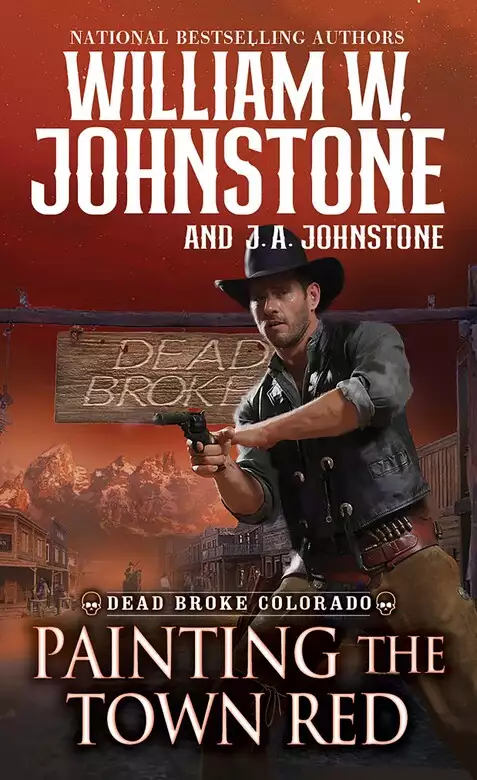

Welcome back to Dead Broke, Colorado. Where the latest discovery—a giant boulder of zinc—sparks an all-out frenzy of greed and gunfire that rocks the Rockies to their core. . . .

Ever since the silver market crashed, the mining town of Dead Broke has been awfully quiet. The local marshal—legendary gunman Duncan “Mick” MacMicking—doesn’t have much to do besides outshoot the occasional greenhorn looking to challenge him. But all this peace and quiet is about to end. After getting trapped in a cave-in, Mayor Nugget unearths a mineral to rival his famous “Hope Diamond of Silver.” He calls it the “Liberty Bell of Zinc,” a massive boulder of pure zinc carbonate. But when word of his discovery gets out, the quiet little boomtown of Dead Broke goes boom—again—with a vengeance. . . .

First, a scheming banker shows up to cash in on Nugget’s prize. Then, an outlaw gang arrives to rob the bank and steal the Liberty Bell. After a blood-soaked shootout, Marshal Duncan decides he’d better get that big rock out of town before more people die. Fortunately, the mayor has received an invitation to display his zinc boulder at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show in Chicago. There’s just one problem: getting it there without getting killed. Thanks to all the publicity, every greedy sidewinder in the West knows which train they’re taking. And once the shooting starts, this train will be dead on arrival. . . .

Release date: September 30, 2025

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Painting the Town Red

William W. Johnstone

No one would argue that the town was much quieter than Dead Broke, located some two miles high up in what was known as This Side Of The Slope, had been during those lawless days. Days? Dead Broke’s reputation had grown so much, its lawlessness had lasted years, but eventually had settled down, boomed, prospered, drawn attention as a silver mecca everywhere from San Francisco to New York City—and even overseas. But that had been way back then, during the glory days, when silver was worth the months or years it might take to find. These days, Dead Broke sure had a lot fewer people, now that the silver market had crashed and the Panic of ’93 kept painting a grim picture for the future of this, and other, mining towns.

The town had boasted a population of right around ten thousand in the mid-1880s. Now it was down to …?

If Duncan “Mick” MacMicking had to guess, a hundred? Maybe 150? And most of those would take off for lower elevations soon, because this high up, winter came early and held on for a long, cold time.

But Duncan liked things quiet. As Dead Broke’s town marshal, he found a certain pleasure in living in a small town, too high up for most snakes, too high up for most people. Sure, the altitude at two miles up would tax a fellow’s lungs now and then, especially after the first snow had fallen—just a few inches, not the feet that were sure to dump on these mountains in the coming months.

Only a few hardcore miners remained in town, and they weren’t digging for silver or gold, but lead and zinc. Duncan had never heard much about lawlessness and death and murder over zinc and lead.

He sat in Sara Cardiff’s Crosscut Saloon, playing penny-ante poker with Ben Usher—like Duncan, a man who had earned a reputation as a top gun and villain (though Usher happened to be a decent fellow) because of those hack writers who kept turning out cheap novels about plenty of wild Westerners—the same scribes that had helped give Mick MacMicking a reputation. Old Syd Jones, like Duncan and Usher, had also become something of a legend across the West.

And here they were, lazing away in a dying Colorado mountain town.

Of course, the way Duncan and Usher saw things, Syd Jones deserved his reputation. He was a stand-up guy, honest to his ramrod straight backbone, and now that he was off the hooch, just as fine a fellow as anyone could find—especially on This Side Of The Slope.

Yawning, Jones left the bar with a coffeepot and walked over, taking his good, sweet time, and topped off the mugs in front of Duncan, Usher, and Logan Ladron, the only dealer who had gumption enough to stick it out in what was now the only gambling place in Dead Broke. In fact, now that the Lucky Dice Gambling Hall was out of business, it was the only place where a fellow could get a drink of whiskey outside of Percy Stahl’s beer mill or—if they wanted to risk their tongues, teeth, throats, stomachs, and souls—buy some homemade hooch from Mayor Nugget.

Coffee, smelling powerfully strong, splashed into the neglected mugs in front of Duncan and Usher, and Jones set his own mug on the table before moving to a faro layout that now served as a good enough place to set coffeepots, hats, woolen scarves, and one sawed-off shotgun. Dragging a chair over, Jones settled into it, picked up his cup, and sipped.

Usher dealt two cards to Duncan, then took three himself. Logan Ladron had folded without taking a draw.

“Your bet,” Usher said.

Duncan studied his hand for just a second, then tossed the cards onto a nickel and two pennies—the nickel being the ante, and the pennies being Duncan’s bet and Usher’s call.

“I fold.”

Usher looked at his hand, and, stifling a yawn, threw his cards atop Duncan’s.

“Me, too.”

“Watch ya mean, you is foldin’?” cried Mayor Nugget, sitting at another table, looking through a mail-order catalog. He closed the big book and pointed a gnarly finger. “’Em fellas done folded. That pot’s yours.”

Usher left the coins on the table, but gathered the cards, straightened the deck, and passed it to Ladron.

“It wouldn’t be respectable to take money with what I was holding.” He set the deck in front of Ladron. “Your deal.”

The gambler stared at the deck. He had stopped drinking coffee an hour ago and had been spending more time moving his five pennies, two dimes, and one nickel around. He studied the deck and shook his head.

“Never thought I would say this, but I’m just too bored to play poker.”

Nugget slammed the catalog shut. “Miss Sara pays you to deal poker, son, or twenty-one or checkers.”

Ladron stared at Nugget, then shot glances to Jones, Usher, and Duncan. He shook his head, whispered, “Dealing checkers,” and picked up the deck, which he started shuffling.

Usher found his cup and took a swallow. “Nah, Logan, you’re right.”

“Yeah,” Duncan agreed.

“Y’all ain’t gonna play poker no more?” the mayor asked.

Duncan looked at the clock above the bar—again. How many times had he checked his watch or that clock? How many times had he looked at a calendar over the past several days? He couldn’t even remember how long he had been inside the Crosscut Saloon.

“Want to look at this big book?” Nugget asked. “It’s got all sorts of pictures in it.”

Ladron shook his head. Usher drank more coffee. Syd Jones had opened a blade on his pocketknife and started cleaning his fingernails.

“They’s wagons and stickpins and real perty pocket watches. And pistols. And boots.” He turned a page. “And dishes.” Another page. “More dishes.” Another page. “Lots of dishes.” He looked up, sighed, and closed the catalog, pulled on his beard, and looked at Syd Jones.

“Can I have some of your coffee, Syd?”

“Sure.” The old lawman rose. “It’ll break up the monotony.”

“The what?” Nugget asked.

Syd Jones didn’t answer. He found the pot and walked over to where the mayor sat.

“Where’s your cup?”

The only things in front of Nugget were his jug and the catalog.

“Ain’t got one.”

With a chuckle, Jones placed the pot on the table and walked toward the bar.

“Nugget,” Duncan said, “can’t you get your own cup?”

The mayor stared a moment at Jones, who did not stop, and then looked back at his marshal. “Syd’s fetchin’ it. He’s just your depitty. I’m mayor. I’ve got important things to do.”

Duncan shook his head. Syd was already to the bar, moving behind it to find the coffee cups. Then he stared at his old friend.

“This remind you of something?” he asked.

Ben Usher’s snort passed as a laugh. “Yeah. Yesterday.”

Ladron turned over a card, then put it on the bottom of the deck. “I was …” He had to stop in order to stifle a yawn. “I was thinking the day before.”

A door squeaked open upstairs, and Duncan turned around to stare up.

Sara had been awake for a while, but now she had taken a bath, and from where Duncan sat, she looked wonderful. She wore a blue dress—a warm blue, like her eyes—and her blond hair looked different, but he couldn’t figure out what she had done to it. It didn’t matter. She was beautiful. She always looked beautiful.

“Good morning, gentlemen,” she called out from the balustrade.

Duncan looked again at the clock behind the bar, and again stared at his watch. Yes, it was still morning. Some hours before noon. He had hoped it would be a bit after twelve, at least. This day was dragging on, just like yesterday and the day before.

Well, folks said winter days passed the longest.

But it was barely autumn.

This year might never end. This day might last for all of eternity.

Sara was moving toward the stairs, and when she started heading down, Duncan decided that if today lasted forever, well, that wouldn’t be bad. No. That wouldn’t be bad at all.

“Is there any coffee down here?” she asked when she stood on the ground floor. “I thought I smelled some.”

Nugget sprang from his chair and pointed at the pot on his table. “It’s right here, Miss Sara. Right here. Come on over, and I’ll run and fetch ya a cup.”

And he took off, moving like a man much younger than his years. “Pull up a chair if you wanna,” he said, staggering into an empty table, almost overturning it, and then slid to a stop at the bar. He moved behind it, stopping at a bottle of brandy on the backbar, uncorked it, took a swig, set the bottle back down, but not the cork, and disappeared.

Sucking in a deep breath and holding it, Duncan waited for that dreadful sound of a glass or stoneware breaking, or some other catastrophe, but Nugget came up in a moment, and he held a pewter mug, and then he hurried back.

Duncan turned around. Sara had not moved.

Nugget slammed the mug next to the pot and spun around, trying to smooth his dirty vest and fix the collar of his coat.

Usher stared at the coins before him and shook his head, stifling a laugh.

Sara started moving slowly, smiling as she passed the would-be cardplayers, and stopped at the table.

“Thank you, Mayor Nugget,” she said, and reached for the pot.

“Nugget, aren’t you—” Ladron started, but stopped at Duncan’s Shhhhhhhhhhh.

Usher whispered: “You want her to get her hand or something scalded by that ol’ coot?”

She filled the mug, set the pot down, and raised the mug in a toast toward Dead Broke’s mayor, then back at her other friends, and walked to the batwing doors and peered outside.

“Oh, it snowed last night,” she said.

“Just a dusting,” Ladron said.

“What a beautiful morning.” She sipped coffee, breathed in deeply, and, still looking outside, said, “It doesn’t feel too cold.”

“Sun’s up,” Usher said.

“Sun’s hotter at twelve thousand feet,” Duncan added.

“Snow’ll be melted.” Syd Jones yawned. “By afternoon.”

“Oh, it’ll be back, that’s certain sure,” Nugget said. “I been up here long enough to know that. We’ll be snowed in by November.”

“Cut off from all of civilization,” Syd Jones agreed, nodding while reaching for his cup of coffee.

“Snowed in till spring.” Duncan looked long at Sara Cardiff. “What a wonderful thought.”

“No drunks.” Syd Jones nodded.

“No dumb punks wanting a reputation,” Ben Usher whispered.

“Lots of snow cream,” Nugget said, smacking his lips. “Snow cream. With milk and sugar and sweetened with my special brew.”

“And ten degrees below zero feels like summertime,” Ladron said, shaking his head. “Good thing I won that buffalo robe off of Dylan Pugh three weeks ago.”

Sara drank more coffee and turned back to walk to the only people in her saloon.

“And how are you all doing?”

All answered in unison.

“Other than complaining about the weather.”

Syd Jones was the only one who remembered to pull out a chair for the beautiful woman, and she thanked him, then settled down.

The silence fell quickly.

“One good thing about winter,” Syd Jones said after a long while.

“What’s that?” Ladron asked.

“Well.” The old lawman eyed Usher, then Duncan, and said, “Those young toughs looking to get a reputation won’t be coming up here to paint the town red.”

Usher raised his cup and clinked it against his old mentor’s. “That’s a fact,” he said.

Then came a shout from outside.

“Marshal MacMicking! Marshal MacMicking!”

A moment later, Joey Clarke, a smart twelve-year-old, raced through the batwing doors, which banged behind him. He rushed toward Duncan and pointed out the window.

“There’s a man riding into town!” he yelled as he slid to a stop. “A man.”

The boy’s eyes were wide open, and his face pale. Everybody was standing now. Sara ran, and stood behind the boy, holding his shoulders. “Easy, Joey,” she said. “What is it? What’s the matter, honey?”

All of the men formed a semicircle around Little Joey and Sara.

“Easy, Joey,” Duncan said.

“Men often ride into Dead Broke, Joey,” Nugget said.

But not lately, and not this time of year, Duncan thought.

“It’s likely that this hombre just wants to see my Diamond Nugget of Silver. Gosh, we ain’t gotten no visitors to see my most wonderfullest discovery—the reason for this city today—in some time. But if he’s got money for the tour.”

“No, no, no,” Joey managed to choke out between breaths.

“I’ll go see that feller.” Nugget started for the door.

“No, Mayor Nugget!” Little Joey screamed. “Don’t step outside. He might shoot you dead.”

That stopped Nugget. That stopped everyone.

“Marshal!” Joey stopped, slowed down, and managed to catch his breath. “Marshal. This stranger. He’s wearing two pistols! Ain’t No Firearms Allowed still the rule of law?”

Duncan shot a glance toward Usher, who pushed back his chair.

Usher sighed before he spoke in a tired whisper: “No dumb punks wanting a reputation …”

Yeah, Duncan thought. That had been a hopeful wish, but an improbable one these days—even with winter coming. As long as there were gunfighters, there would always be challenges like this.

It was enough to make a man who had to wear a gun wish he had never strapped one on. Then again, Duncan could recall those years—before Syd Jones whipped the devil out of him and some brains into his noggin—when he had been a punk with a gun and, till he met Syd Jones, what he thought was a real fast draw.

The next voice came from outside.

“MacMicking. Or you, Usher. I’m callin’ you out. I don’t care which one. Just step outside … and get ready to die.”

Ben Usher sighed, shook his head, and slowly pulled the ivory-handled Colt Thunderer from his holster. He checked the cylinder, and said, “I reckon it’s my turn,” before sliding the double-action revolver into the holster.

“No.” Pushing himself out of his chair, Duncan MacMicking tested the heavy Schofield .45 in his holster. “I reckon I’m still marshal of this town, so I guess this is my job.”

“Duncan.” Sara Cardiff’s voice was barely a whisper.

He gave her his most reassuring smile, nodded at the others, and walked toward the batwing doors, but made a detour around the bar, disappeared underneath, and came up with a sawed-off ten-gauge Greener. He opened the breech, pulled out one shell, slipped it back into the barrel, then did the same with the second shell. Once he snapped the barrels back in place, he moved to the doors, looking through the opening to find the latest gunfighter—or what folks might call a gunfighter these days—still sitting in the saddle of a piebald mare.

The kid was, as the saying went, advertising a leather store. Step-in chaps that hadn’t a scratch on them, and darn little dust for a fellow who had been climbing up this mountainside. The boy, wanting to look his best, must have stopped at the stream and cleaned himself up. Black hat, with a tie-down string to keep the wind from blowing it to Nebraska. Black shirt. Black ribbon tie. Black gun belt. Black pants. Black boots. Black frock coat. Black spur straps. And the boy was as white as Christmas snow.

But there was that black holster that the tail of the coat had been pushed behind, with the pearl handle of what looked like a single-action Colt reflecting some sunlight.

The kid sported fuzz over his mouth and what he probably fancied as a menacing underlip beard. His face showed recent sunburn, which likely meant he hadn’t grown up a bored farm or ranch kid. Probably came from some good family in a city. Denver, maybe, or Colorado Springs. He didn’t look like the type that could have ridden much farther than those two towns.

Did I look like that when Syd Jones beat the tar out of me?

Duncan shook his head at that thought.

“Which one is you?” the boy managed to ask.

Duncan couldn’t help but blink. Blinking was dangerous when you faced a gunman. The good ones, the smart ones, always sought that edge, and a blink gave them a really good advantage. Blinking was a mighty good way to get yourself killed. But the boy was too young to know that.

The question ran through Duncan’s head again.

Which one is you?

The kid had spoken loud enough that Ben Usher let out a chuckle, and had Usher been standing here and Duncan was back with his friends, he probably would have done the same thing.

But standing here behind those batwing doors, he felt, well, insulted.

“Does it matter?” he finally said.

The boy shrugged, then tried out his smile of sheer menace. Which did nothing but make him look constipated.

“I like to know who I’m killin’,” he said, deliberately dropping the G so he would sound like he was a veteran of these kinds of shootouts.

Duncan gave a slight nod. “I’m MacMicking. Marshal of Dead Broke.” He tilted his head at the sign that hadn’t blown down yet, the sign that said:

THE CARRYING OF FIREARMS BYANY MAN,TOWN CITIZEN, OR VISITORWITHIN THE CITY LIMITSOF DEAD BROKE—CONCEALED OR IN OPEN VIEW—WITHOUT A PERMITIS STRICTLY PROHIBITEDFINE: $75AND CONFISCATION OF WEAPON

There was a bullet hole in the center of the D in “Concealed,” but that was new. The punk that Ben Usher had wounded in the arm, not a full week ago, had managed to do that. It made the boy happy—happier than he was with the bullet he took in the shoulder for his troubles.

It was something, the kid had said as they carted him to Doctor Aimé Cartier to dig that bullet out and send the boy back to his mama, that he could brag about. He had begged Duncan to keep that sign up. He might want to bring his friends up to see it sometime.

“You’re in violation of the law, son,” Duncan told this latest punk to come up the mountain. “We don’t allow folks to carry firearms within the Dead Broke city limits.”

The boy grinned. “I reckon I’ll just let you try to take this gun from me, MacMicking.”

Slowly, like an actor hogging a scene in some theater, the boy eased out of the saddle, taking his time, and taking his eyes off MacMicking, who figured he could have put twelve bullets in the boy—and that included emptying the .45’s cylinder and reloading his revolver—by the time he was on the ground and standing, still in the street, in front of the entrance to Sara Cardiff’s saloon.

The horse, ground-reined, walked across the street to a water trough out of the line of fire.

Which meant the horse had some sense. Its owner? Not a lick.

The boy turned a few yards away, pushing back the tail of the dark coat and keeping his right hand just inches above the pearl handle of his revolver.

“I’m glad it’s you I’m facing, MacMicking. I would have settled for Ben Usher. But you … you’re the top dog. Or was. Till I rode into town.”

Duncan sighed. The wind was blowing too hard and away from the Crosscut, and Usher was busy talking to Sara, telling her it was all right, that Duncan knew what he was doing, and Syd Jones was stirring something into his coffee and making an awful racket, while Logan Ladron kept shuffling the deck over and over again. No way Usher had heard what that boy had just said—and that was something MacMicking wouldn’t have let him ever forget. No luck, though. It didn’t matter. He slowly shook his head.

“You comin’ out, MacMicking? Or do I have to walk in there and drag you out?”

That stopped the conversation Usher was having with Sara. It stopped Syd Jones from banging that spoon on the side of his coffee cup, and it made Ladron quit messing with that deck of cards that were already worn down. Nugget just smacked his lips.

The wind moaned.

Duncan chanced looks up and down the street. Empty, of course. Like every other street in Dead Broke. There was a cat lying on the busted boardwalk in front of that abandoned general store, and a mouse ran from underneath the boardwalk to a trash bin, but even the cat had no interest in the mouse.

The horse quit drinking, shook its head, turned slightly toward the boy who had brought him up to this out-of-the-way town, snorted, and nuzzled the dead grass at the side of the trough to see if it might be worth chewing on.

“Don’t make me come in there after you,” the boy said. “Ain’t you got any sand in your craw?”

“I’m getting too old for this,” Duncan whispered. Then he pushed his way through the batwing doors that bounded behind him as he stepped onto those planks and onto the ground. He kept right on walking toward the boy, whose eyes widened and whose face grew paler than the noonday sun.

“Th-th-tha …” He raised his right hand—his gun hand, the stupid punk—and pointed at the Greener that Duncan held, left hand on what remained of the hard wood under the barrels, right hand on the iron, trigger finger in the guard, thumb against the hammers.

He walked straight toward the boy.

“That’s a shotgun!” the boy finally managed to call out. “That … that … ain’t … fair!”

Duncan powered forward like a bull.

“What’s fair in a gunfight?” Duncan roared. “How do you think Jack McCall killed Wild Bill Hickok in Deadwood all those years ago? You think Doc Holliday or the Earps gave any of those Clanton boys a chance down in Tombstone?”

The horse, the cat, and the mouse were looking at the boy and Duncan with curiosity. The boy might have been wetting his pants. His right hand had moved away from the Colt and was pointing, in a terribly shaking hand, as Duncan kept walking.

“John Wesley Hardin wasn’t anything but an assassin. And a lot of lawmen I knew weren’t any better.”

Twenty feet separated them now.

“There’s just one rule to a gunfight, kid. Live through it. And you live through a gunfight by the grace of God and luck. If I had any sense, the second I got through those batwing doors, I would have blown you in half.”

That’s when the boy fell to his knees, bowing his head into his hands and sobbing like a freshly spanked newborn.

“Please,” he begged. “P-p-p-p-pl-please … don’t … d-don’t … k-k-kill me.”

Duncan stared down at the pathetic figure. He saw how white his hand and fingers were that gripped the Greener. He realized that he had never cocked the hammers. That, he figured, might have been a good thing. As riled as he was at this green, stupid punk of a kid, Duncan could have easily touched the hair triggers and with the buckshot in those loads, that cat and mouse would have had a bountiful supper—had just one of those double triggers been pulled.

His heart pounded against that tin star pinned to his vest.

“Please don’t kill me,” the boy begged, sniffling, tears sprinkling the dirt on the street. “Please. Please. Please. My mama. My mama. Oh, Mama, come help me.”

The batwing doors banged again, and Duncan felt the saneness return to his head and heart. He shifted the Greener to his left hand, then knelt in front of the aspiring gunfighter. His right hand touched the shoulder of the frock coat, tightened, but he made his voice as friendly as he could.

“Stand up, boy,” he said. “Stand up.”

The kid raised his head. Duncan had seen livelier faces on corpses, but he was glad this kid wasn’t a corpse. He came close to being one, though.

He helped the boy to his feet, then pushed away the tail of the black coat, and pulled the ivory-handled, nickel-plated Colt from the holster.

“The fine’s seventy-five dollars, boy,” he said, “and confiscation of the firearm. But I’ll just take this Colt.”

It was one of Colt’s newer models, an 1892 New Army, looked like a .38 caliber. A .41-caliber would likely have been too powerful for this snot-faced little boy. Probably cost him twelve bucks at a gun shop or one of those catalogs that sent anything through the mail. Or maybe he had borrowed, or stolen, it from his pappy. Double action. Duncan always preferred the single-action models. He never trusted those self-cockers. He had been using the same Schofield for … well, he didn’t feel much like counting those years.

With the kid on his feet, Duncan started steering him toward the saloon, where Logan Ladron, Syd Jones, Ben Usher, Nugget, Little Joey, and Sara stood waiting on the boardwalk. Another figure appeared across the street.

Duncan saw the man and nodded. “No need of your services this time, Doc,” he told Aimé Cartier.

The doctor crossed the street, anyway. “I guess I could use a bracer.”

You ain’t the only one, Duncan thought.

“You … you … you … takin’ … taking me … taking me … to jail?” the kid asked.

Duncan almost laughed. His jailer, Winston DeMint, probably would enjoy having someone to talk to these days.

“I think the gun is enough of a fine,” he told him. “But”—he nodded at the entrance to Sara’s saloon—“I’ve never run a man out of town without letting him get something to eat.”

It was a long ride down the mountain.

“Can I have a whiskey?” the boy asked.

“I said eat.” Duncan hoped he sounded tough and strong. Though he was thinking that he sure would like a whiskey right now himself.

He looked over the boy’s black hat and called out, “Any chance we could get this young man some food in his belly before he rides back to …” He leaned closer to the boy. “Where you from?”

“Leadville.”

That was closer than Duncan had figured. But it was still a long ride down this mountain, then up another steep one. It was probably easier to get to Denver.

Sara Cardiff was steering Joey Clarke into the Crosscut, and Logan Ladron followed, likely to help find some food.

Duncan handed the double-action Colt to Usher, who studied it for a moment, then shoved it into his waistband and crossed the street to fetch the boy’s horse.

“Why didn’t ya shoot this punk?” Mayor Nugget said. “Ya had ever’ right to.”

“I was thinking about the city budget,” Duncan said. “We’d have to pay the gravediggers and coffin makers.”

Nugget tugged on his beard, thinking a bit, before spitting tobacco into the street.

“He gonna pay the fine?”

“This’ll do.”

And the mayor liked having that toy in his hand. He probably didn’t realize that a New Army Colt was worth a whole lot less than seventy-five bucks. But it would give Nugget something to play with for a while.

They watered down some coffee for the boy, and fed him cold biscuits and some leftover ham, and Sara tried to warm up some fried potatoes.

“What’s his name?” Sara whispered while the boy showed a marvelous appetite for a kid who had come inches away from being buried in an unmarked grave.

“You know we don’t ask a fellow his name in these parts,” Duncan reminded her.

She snorted, then turned and said, “What’s your name, son?”

“Larry,” he said while chewing a mouthful of ham. “Larry Tuckness.”

“Where do you live?”

He told her.

“Can you get home all right? That’s not an easy ride from here.”

He swallowed, then washed down the grub with weakened coffee. “I can make it. Even if I have to camp sometime tonight.”

“It’s getting cold.”

He drank more coffee. “I’ll be fine.”

“She’s a worrier,” Ladron said with a smile.

The boy finished his food, thanked everyone, and rose, putting on his hat and then noticing his gun belt. He unbuckled it and laid the rig on the seat of his chair. “I don’t reckon I’ll have need of this anymore.”

“I don’t know,” Ben Usher said. “A fellow who knows when to use a gun and when not to use a gun … that’s the kind of fellow a man in my business can respect.”

Duncan took the boy’s pistol from Nugget and set it beside the . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...