- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

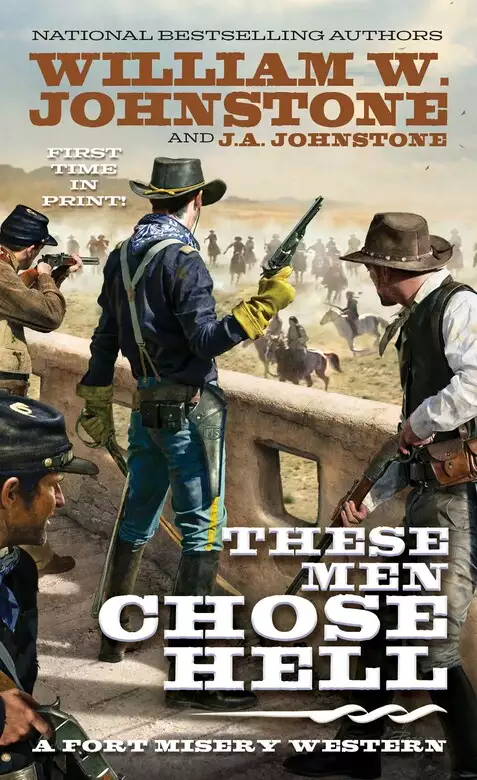

The Greatest Western Writers of the 21st Century return to Fort Misery—where the lowliest dregs of the U.S. ARMY defend the driest patch of lawless desert against the gnarliest killers in the wild, wild West. Sometimes it takes a bad man with gun to stop another bad man with a gun . . .

They’re not what you’d call “the good guys.” They’re a mangy pack of despicable deserters, thieves, mutineers, and worse. But as condemned soldiers in an overstretched army, they were given a choice: death by hanging or serving out their time in a hell on earth.

These men chose hell.

Located at the farthest edge of the Yuma Desert, Fort Grierson is a magnet for trouble. Vicious attacks by marauding Apache and gunslinging outlaws are practically a daily occurrence—and the men holding down the fort are hardly any better. Hence the nickname Fort Misery. When a group of professors show up at the fort in search of lost treasure, a series of gruesome murders begins. The men of Fort Misery will have to find the culprit before they all meet a terrible end . . .

Release date: July 1, 2025

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

These Men Chose Hell

William W. Johnstone

“Does Fort Misery get any other kind from Washington?” Captain Joe Kellerman saw the question form on Olinger’s face and grimaced. “Here, Saul, see it for yourself.”

Olinger took the dispatch and read:

Then, in a different hand:

“I thought Uncle Billy was a friend of yours,” Olinger said. “You helped protect his left flank during his March to the Sea.” He laid the orders on Kellerman’s desk, reverently, as though they were pages torn from the Bible.

“So did I,” the captain said. “Once he slapped me on the back and promoted me to full brevet colonel, and now he changes hands, stabs me in the back, and gives me an impossible order.”

“You can’t put your trust in generals, and you’re dealing with two of them,” the sergeant major said.

Olinger had treated the orders like a holy document, but Kellerman had no such reverence. He took two glasses and a bottle of bourbon from a desk drawer and slammed them down on the papers.

“A drink with you, Saul,” he said.

“Don’t mind if I do, Joe,” Olinger said. He and the captain had fought in the war together, and the familiarity came naturally to him, but only when there were no enlisted men around.

Kellerman poured the drinks, downed his in one swallow and refilled his glass. “All right, Saul, give me the rest of the bad news.”

“Three officers and twenty-eight enlisted men, four of them in the infirmary and one of them, Private Shanks, is running a fever and isn’t likely to live.”

“What does Mrs. Zimmermann say about him?”

“That he isn’t likely to live.”

Kellerman looked as though he was trying to put a face to the name and the sergeant major said, “Small, even for a cavalryman, blue eyes, black hair, a Reb, he fought in John Bell Hood’s Army of Tennessee . . .”

“I remember now,” Kellerman said. “He knifed somebody . . .”

“Two people, a lady of the evening and her pimp. The woman lived but the pimp died.”

“So the Army offered him a choice, the noose or Fort Misery.”

“Yes,” Olinger said. “He chose Fort Misery.”

“Bad choice.”

“Joe, all of our enlisted men made the same mistake and then realized what they’d done was to arrive in hell early. It’s a fact of our existence.”

“Look out the window and see another fact of our existence,” Kellerman said.

“I don’t have to. I know what’s out there,” the sergeant major said. “The view never changes.”

Thrown deep into the Arizona Territory’s vast Yuma desert, the post’s official name was Fort Benjamin Grierson but seldom used. It looked like a ramshackle shantytown that had fallen from the sky during a great storm and landed on a sea of sand. Fort Misery was manned by a sweating, understrength troop of cavalry composed of deserters, thieves, malingerers, mutineers, murderers, and rapists. “A grubby bunch, the scum of the earth,” Lieutenant James Hall called them. Officially, the troop didn’t exist. It had no regimental affiliation, wasn’t allowed to carry a guidon, and in Washington, any inquiry into its rumored presence was met with blank stares. Since it was somewhat of an embarrassment, the Army had been quick to sweep the fort under the rug and there it stayed, the silence surrounding its formation unbroken.

The post was such a pariah, supplies from Yuma were dropped about two miles north of the fort at a place called Devil’s Rock, a ten-foot-tall granite monolith shaped like a crouching human being. The civilian teamsters would come no closer to Fort Misery and its evil reputation, and wasted no time throwing off their load before hightailing it away from there. Withal, the officers and men of Fort Misery were on a voyage of the damned on an ocean of sand . . . and death would be their only port of call.

Kellerman rose from his desk, and stepped to the window, looking down at the parade ground that had never seen a parade. Triangles of dust had collected on all four corners of the glass panes, one of them marred by a bullet hole and never replaced. Like the fort itself, repairs were not a high priority, though the carpenter, Tobias Zimmermann, did his best to keep the buildings hammered together, just as his wife, Mary, the post’s cook, nurse, and laundress strived to keep the soldiers fed and reasonably healthy.

“Second Lieutenant Cranston is coming in with the supply wagon,” Kellerman said. “I wonder how the army plans to starve us this month?”

“There’s one way to find out,” Sergeant Major Olinger said. He stood to attention and saluted. “Permission to inspect the supplies, sir.”

Kellerman returned the salute. “Make sure Lieutenant Hall’s snuff arrived safe and sound from his dear mama. He’s been as worried as a frog in a frying pan about the stuff for weeks.”

Mary Zimmermann was already overseeing the unloading of the supplies when Sergeant Major Olinger arrived. He looked at the piled-up sacks and crates and said, “How is it, Mrs. Zimmermann?”

“Looks no better and no worse than usual,” the woman said, frowning. “At least they remembered the raisins this time. I can’t make plum duff without raisins, sergeant major.”

“No, indeed, ma’am,” Olinger said. “And I’m glad they arrived safely.”

Mrs. Zimmermann was surrounded by salt pork and salt beef in barrels, sacks of beans, coffee, hardtack, salt, brown sugar, and vinegar and molasses in jugs. There were bottles of bourbon packed in straw for the officers and jugs of cheaper whiskey for the other ranks, General Sherman aware that the fort had no sutler.

“Hey, you scoundrel, easy with those crates,” Olinger yelled to a clumsy private. “The officers’ bourbon is in one of those.”

“And Lieutenant Hall’s brandy,” Mrs. Zimmermann said.

“From his fond mama,” Olinger said. And then to Lieutenant Cranston, “An uneventful trip, sir?”

“At sundown on our second day out, Private Ritter and myself heard drums in the distance of the night. Corporal Lockhart couldn’t hear them, and neither could the other private, but they were there all right.”

“Apache?” Olinger said.

“That would be my guess. I’ll let Captain Kellerman know.” Suddenly the young officer looked like the bearer of bad news. “By the way, sergeant major, there are three wagons coming in behind us.”

Olinger was stricken. “Don’t tell me, sir.”

“Yes, I’m telling you, three professors all dressed up in safari clothes, boots, and pith helmets are here to dig up our parade ground in search of Spanish treasure. According to the gentleman who spoke to me, Professor Oliver Berryman, they’re fresh from a British Museum expedition to the Valley of the Kings sponsored by the Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities. Apparently, they discovered a royal scribe’s tomb with a curse on it and are eager for more triumphs.”

“After all the Comanchero trouble we had last year, Captain Kellerman didn’t think they’d come.”

“Well, they’re here, sergeant major, or they will be in about an hour or so.”

“And they’re bringing a curse with them. The last thing Fort Misery needs is another curse.”

“It’s just a piece of superstitious nonsense written by some pencil pusher three thousand years ago,” Atticus Cranston said. “I wouldn’t worry about it.”

The second lieutenant was a tall, slender young man with earnest brown eyes and dark red hair showing from beneath his kepi. His top lip was fuzzed with the hopeful beginnings of a cavalryman’s mustache, and like everyone else in Fort Misery, he was covered from hat to boots in gray dust. He wore his revolver and saber well and had given a good account of himself in the previous year’s battles.

“Sir, if this was Fort Concho, I’d agree with what you just told me,” Olinger said. “But this is Fort Misery, and therefore, I’ll worry about it.” A deep sigh, then: “We’re already cursed, but I guess another one won’t make any difference.”

Lieutenant James Hall was officer of the day when the sentries reported that the mule-drawn wagons were coming in, two covered, the other open, each with a driver at the reins, three older white men and an Asian fellow in a brocade robe walking solemnly behind them.

“Those are the perfessers by the look of them, sir,” the sentry said.

“By the lord Harry, they look like a grim lot,” Hall said. “There’s not a general hidden among them, I hope.”

“Sir, they don’t look like generals,” said the soldier, a tow-headed youngster with freckles. “More like them perfessers that are always talking about strange stuff.”

“Ah, yes, the prodigal professors! Well, show them in,” Hall said. “It will be a nice change to talk to my intellectual equals. And be respectful, you ruffian.”

The drivers, three rough-looking muleskinners, parked the wagons on the parade ground, and the occupants, three skinny older men wearing tan clothes and pith helmets, staggered toward Lieutenant Hall.

The apparent eldest of the three was a tall, cadaverous man with long gray hair, rough-cut beard, staring hazel eyes that Hall at once decided were half-mad, and a sharp, pointed nose that was red in color, peeling and sunburned.

“Officer, oh, officer,” the man said, in a grating, whiny voice replete with a posh English accent, “what a dreadful journey, what an ordeal we’ve suffered. Sun, heat, little water—and for the past three days, only disgusting dried meat and ship’s biscuit to eat. I swear, we are almost dead from the horror of it all.”

One of the wagon drivers, a rough-hewn character whose expression bordered on the villainous, said, “Perfessor, the trials of your journey was no fault of ours. We only drive the wagons. We don’t control the weather or the vittles. Which, it was all explained to you afore we left Yuma.”

“Yes, it was, Mr. Belcher, but we did not anticipate its severity. Many of my countrymen have voyaged to these lands and spoken nothing but praise upon their return.”

“And what is your name, and why are you here?” Hall said to the whiny older man.

“My name is Paul Fernsby, Professor Paul Fernsby, and these are my associates, Professors Julius Dankworth and Oliver Berryman. Oh, listen to my voice. My throat’s as dry as dust in a mummy’s pocket.”

“We anticipated your arrival and we’re glad to have you here, sir,” Hall lied. “Private, pass around your canteen to the gentlemen.”

After tilting the canteen to his parched mouth, water running down his chin, Fernsby wiped off his patchy beard with the back of his hand and said, “Young man, you have a right to be glad since you’ll have a front seat at the greatest archaeological triumph since the 1813 discovery of the Temple of Ramesses the Second by the circus strongman turned archaeologist, the incomparable Giovanni Battista Belzoni. Walking in the great man’s shadow, I’m here to uncover the remains of the lost army of the Spanish Conquistador Don Esteban de Toro and—and this should be of interest to you—his rumored treasure chest.”

“Where is all this?” Hall said.

“‘Where is all this?’” Fernsby parroted. “Do you hear that Professor Berryman? Professor Dankworth?” He smiled and said, “Why, young man, if my map is correct, and I’m certain it is, you may be standing on it.”

“So where do you want us to dump your stuff, perfesser?” Belcher said. “If it ain’t too much to ask.”

“Right on this spot, my man,” Fernsby said. “The dig begins right here.”

“I can’t allow you to do that until I speak to my commanding officer,” Hall said. “Army protocol, you understand.”

“Which is of no concern of mine,” Belcher said. He turned in his seat and said, “Bob, get that stuff unloaded, and let’s get out of here.” He looked at Hall, shook his head, and said, “Which he’s the laziest of my lazy sons.”

“Halt!” Lieutenant Hall said. “As I told you, you need the permission of Captain Kellerman.”

Fernsby reached into his coat and produced a sweat-damp, lank envelope. “Right here is all the permission I need. It gives me and my archaeologist colleagues permission to dig at Fort Benjamin Grierson without let or hindrance.” He held up the letter inside as though it was a sacred scroll. “Look at the signature, young man, and prepare to be impressed.”

Lieutenant Hall read, and then, shocked, said, “It’s signed by President Grant.”

“Indeed, it is. The president is a close personal friend of mine. One of his cousins is wed to my cousin Gertrude, and that makes us almost family.”

“Close enough for me,” Hall said. “I’ll take you to Captain Kellerman.”

“Julius, Oliver, stay with the equipment,” Fernsby said. “I’ll be right back.” Then, “Mr. Belcher, after you finish unloading, you are dismissed from my current employ. You may take one of the wagons and provisions and water enough to get you back to El Paso.” He dug into his pocket and produced a gold coin. “Here’s a little extra for all your trouble.”

Belcher smiled and said, “Which is the act of a true gent as ever was.”

“Now get busy, man, finish the unloading, and be off with you,” Fernsby said.

The president’s letter in mind, Lieutenant Hall decided to be ingratiating. He said to Berryman, a man as gaunt as his boss but two feet shorter and possessed of hollow eyes and temples to match. “During the war I served with a captain named Oliver. We called him Ollie.” He smiled. “Does anyone call you that?”

Berryman spaced out the words, stressing their severity: “No one—ever—calls me—that.”

Deflated, Hall said, “Ah, then Oliver it is.”

“No, Oliver it isn’t. You will address me as Professor Berryman. Do I make myself clear, Lieutenant?”

“Clear as a bell, sir,” Hall said. “Would you care for a pinch of snuff?”

“And what did he say when you offered him snuff?” Captain Joe Kellerman said.

“He said it was a wicked substance used only by barbarians,” Lieutenant Hall said. “I must say it hurt my feelings a little.”

“You’ll get over it. The professor changed his mind and decided to remain outside. Any idea why?”

“He wants to show you where he’ll dig his trench.”

“His what?”

“His trench. Apparently, it’s what archaeologists call a hole in the ground.”

“You can’t dig a trench in sand.”

“Begging the captain’s pardon, but I think you should tell him that.”

“All right,” Kellerman said. “I’ll go talk to him. What’s the name again?”

“Professor Fernsby.”

Groaning, Kellerman stood, broad chested and handsome despite the bags under his eyes from overdrinking and undersleeping, thanks in no small part to being in charge of the godforsaken fort and the disgraced soldiers within it. He buckled on his .45 Colt Single Action Army revolver and grabbed his hat off the rack, settling it on his head. In contrast to the rugged captain, Lieutenant Hall looked fresh and well-rested, his black hair falling in shiny ringlets to his shoulders and blending into his magnificent beard, the very model of an officer.

“All right, Lieutenant, lead me to him.”

“Finger or toe?”

“Neither! Let me go you—you lunatics!”

“If you don’t pick one, I’ll take ’em both. So, I ask you again, finger or toe?” The man waved a knife blade perilously close to the young soldier’s face, and the soldier whimpered and blanched white under his tan. The knife wielder was U.S. Army Private Jack Nelson, a hard case who had landed at the hellscape of Fort Benjamin Grierson for a list of very good reasons. Given the choice of the fort or twenty years in Yuma prison for the rape and murder of a prostitute in Dallas, he chose Fort Misery—a choice he often regretted, since Yuma might have at least had better food. His current wrath, focused on the teenage soldier he knew only as Private Wesley, secretly filled him with a rare glimmer of joy, violence being his most treasured hobby.

Nelson was rather unremarkable as a gunman and a soldier, and so it was for his looks: his only defining feature was a giant beak of a nose that paired with his beady eyes and balding pate gave him the appearance of a demented vulture. The squirming Private Wesley meanwhile had the face of an altar boy, flushed rosy cheeks and a soft curve to his chin, that made him look very much like a child. Innocent, though, he was not, as Wesley had ended up at Fort Misery for thievery and being a general nuisance across several towns, crimes that would otherwise have stuck him in the pen for a decade if he’d chosen prison.

But currently, young Private Wesley was held firmly by two feral-looking men, one old and fat, one young and thin as a beanpole, and both grinning like crocodiles while they waited for the show to begin. All four men were sweating buckets in the wooden storage room that had become an oven beneath the blazing desert sun, dark circles in the armpits of their faded blue shirts.

“Puh-puh-puleeze just lemme go. I gave it back to you, didn’t I? It ain’t count as a crime no more when you got it back,” Wesley yelled, terror giving him a stutter and high, keening voice.

“Puh-puh-puleeze tell me which you’d rather lose, boy. I’m at the end of my patience with you,” Nelson said, sneering, the mocking stutter drawing guffaws from his accomplices. When no reply but sputtering came, he said sharply, “Right, well, time is up. I’m taking them both. Say, Johnson, help me get one of his boots off.”

Nelson squatted and began to untie the brittle boot in question, which was caked with dust and cracked from lack of attention with a polish and brush to preserve the leather. At this, young Private Wesley started to squeal like a stuck pig, his fearful voice so loud it carried across the barren parade ground outside the shack. Nelson had just managed to remove the boot and a holey sock and was trying to select a toe when the door flew open with a bang. The four men flinched, and Nelson accidently cut a slice across the arch of Wesley’s foot, making him shriek even louder.

Joe Kellerman, followed by Lieutenant Hall, stormed into the room. “What in the hell is the meaning of this?” he demanded in a stern voice.

“They’re tryin’ to kill me!” Wesley cried, sinking to his knees as the two men holding him were forced to let his arms go so that they could snap off halfhearted salutes to their commanding officers.

Nelson pointed at the young private with his knife. “Sir, he’s a thief. He took two—that’s two!—whole double eagles from beneath my mattress, and then a photo of Johnson’s favorite gal from beneath his. We’re teaching him a lesson. I told him he could choose a finger or a toe to be cut off. That way he’ll always have a reminder why thieving is an unsavory path unless performed with the dignity of an outlaw. Can you see Jesse James stealing from beneath a fella’s mattress? It’s indecent!” He stopped to draw a breath. “Sir.”

“I see,” Kellerman said. “Did you hear that, Lieutenant Hall?”

Hall made a “tut-tut” noise and shook his head at the teary young private, “I heard, Captain. Shameful, you villain, how could you steal from your own comrades?”

Private Wesley sobbed. “I gave it back. I gave it all right back.” He moaned in terror.

“Is this true, did he return the booty in a prompt fashion?” Kellerman asked of Nelson, who looked unsure, but replied, “Well, yes—but that don’t make him no less of a thieving rat, do it?”

“What say you, Lieutenant Hall, does that make him any less of a thieving rat?” Kellerman said, stepping further into the room and glowering down at Wesley.

“No, sir, it does not—especially if the photo of the gal was of fine quality,” Hall replied earnestly.

Johnson reached behind him and took the photo from where it was tucked in his suspenders, being too large for a pocket. “It’s of real fine quality, sir. Her name is Daisy Mae and she said she loves me, and I love her.” He handed the photo over to Kellerman, who studied it before passing it to Hall.

“Well, she’s . . .”

The photo showed a woman with a face like a hatchet, who’d clearly come to an age when her best days would soon be through, heavy rolls of fat around her belly stretching the ruffled satin dress she wore. Hall looked at Private Johnson, a man who reminded the lieutenant of the Yuma’s black-footed ferrets that popped out of gopher holes to study humans curiously: thin, long, and pinched about the nose and mouth.

“She’s a perfect match for you, private. Bully for true love!” He handed the photo back with a smile and ignored the bemused look Kellerman shot him.

Kellerman stroked his majestic calvary mustache. “So you think the suitable punishment is to amputate a digit, is that correct?”

Before Nelson could answer, Hall interrupted, “In Arabia when they catch a thief, they take the whole hand clean off. Or so I’ve heard.”

“Thank you for that tidbit, Lieutenant,” Kellerman said, glaring daggers at Hall. The last thing any of these men needed was fresh ideas. “And how do you plan to stop the bleeding, once the toe is chopped off?” he asked calmly.

Nelson scratched the frizzy ring of thin hair still holding on by a thread to his scalp, frowning. “Finger and toe, sir—he wouldn’t choose, so it’s gotta be both. I dunno. We didn’t think about that, I suppose.” Then, brightening: “Oh! We can get a hot bit of iron and press it against the stump, I’ve seen it done afore. They call it caut—caulk—cawter . . .”

“Cauterizing,” Kellerman said.

Nelson snapped his fingers, “Yep, that’s the one! I can ask Tobias to heat us up something real good! Let me go tell him.” He made for the door, and Kellerman stopped him with a firm hand on the chest. While looking into Nelson’s beady and nervous eyes, Kellerman addressed Lieutenant Hall.

“Tell me, Lieutenant, do you agree we should mutilate Private Wesley as a reprimand for theft?”

Hall stroked his beard, “Well, it would be fair, sir, yes.” At that Wesley began sobbing again. “But there are roving bands of Apache to deal with, and a man with a missing finger and a missing toe will be, at the very least, quite wobbly when he walks, and it may make it hard to shoot straight, too. I imagine it would be difficult to file the papers if requested, as well. Sir.”

“An excellent observation, Lieutenant Hall. However, we certainly can’t tolerate thievery under our roof, can we? Private Nelson, please give me your knife.” Kellerman held out an expectant hand. Nelson hesitated and then passed the knife over handle first, being careful not to cut himself or the captain on the sharp blade.

Wesley was the color of curdled milk as Captain Kellerman approached him and knelt. “Are you right-handed or left-handed?” he asked, his face and tone placid, as if he was having a conversation about the weather. “Sir, left-handed, sir. Oh, please don’t take my fingers, I need ’em!” Wesley blubbered.

“Is that so, are you good with a gun?” Kellerman asked.

“Kind of . . . I mean, yes, yes, I am excellent with a gun!”

“You’re lying. Give me your right hand. By the way, I’ve heard left handedness is a sure sign of a devilish nature. I’m sure father Stac—Sacks—”

“Staszczyk.” Lieutenant Hall supplied the name.

“Yes, him—I’m sure he could tell you about your wickedness. You should visit him for an act of contrition.” Kellerman took Wesley’s hand and singled out the pinkie finger, as the young soldier turned his face away, not wanting to see the carnage.

“Sir, begging your pardon, didn’t we need to cat’er’ize him?” Johnson said, consternation clouding his face.

“No need, I have a better solution to this dilemma,” Kellerman said, and then without warning he dropped the knife and snapped the bones in the screaming Wesley’s poor little finger. The digit, having had no part in the crime and undesiring of being cracked back and forth, made a sound like breaking twigs. “See here, you scoundrel, you’ll have a month’s worth of healing, and that should be enough to remind you of your misdeeds. I will leave your toe alone. If I get a report that you have returned to your evils, then I will see to it myself that your hand is chopped off like an Arabian, fighting the Apache be damned. Is that fair, Private Nelson and Private Johnson?” Kellerman stood, his back aching as his morning bourbon began wearing off, exacerbated by the heavy sweating brought on by the insufferable heat.

“That’s fair, Captain, I reckon,” Nelson said, disappointed but still pleased by the young private’s howls.

“Can’t say fairer than that, sir,” Johnso. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...