- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

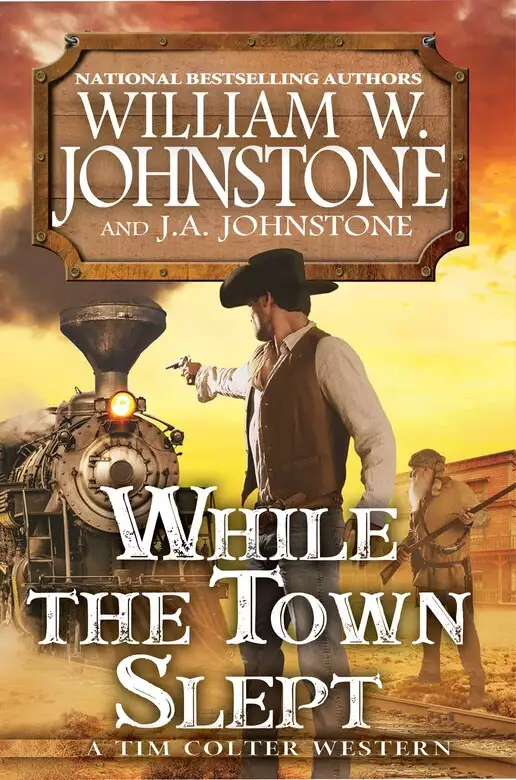

The latest blazing, breakneck adventure in the Tim Colter Western series by the bestselling legends of historical Westerns in which the assassination of President Grant is on the line.

Wyoming Territory, 1873. Tim Colter and his trusted guide, mountain man Jed Reno, are on the trail of a vicious gang of train robbers when they happen upon a bloody and shocking scene. Lying on the ground, barely breathing, a Secret Service agent has been left for dead in the wake of a brutal ambush. His final words: “President Grant . . . assassination . . . Dugan . . . trust nobody.”

It’s a message that chills Colter and Reno to the bone. President Ulysses S. Grant is scheduled to arrive soon in Cheyenne. Dugan is a former Confederate guerilla who leads a notorious gang of cutthroats. And the agent’s last words—“trust nobody”—suggest this conspiracy could reach to the highest levels of American power. Colter and Reno are determined to stop the assassins by any means possible—even if they have to enter hell itself, better known as Dugan’s Den. But to get there, they’ll have to bust a lady outlaw out of prison then convince her to take them to Dugan’s hideout—with a lunatic killer on their tail and the president on a collision course with death . . .

Release date: September 24, 2024

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

While the Town Slept

William W. Johnstone

A woolen muffler flattened the brim of his hat against both ears, looped underneath his chin, and then wrapped around his throat and neck. The plaid bandanna covered his mouth and nose, and while it didn’t keep his teeth from chattering, the heavy cotton likely fought off frostbite for a while. He couldn’t feel his fingers, but the thick gloves still moved when he tightened his grip on the black gelding’s reins one way or the other, while the bearskin coat blocked most of the wind he rode into, though he knew he should have patched that bullet hole a few inches below the left collarbone years ago. The Wyoming wind found a way to whistle through the tiny opening, but at least his vest and flannel shirt blocked some of that frigid air.

Woolen pants and sheepskin woolly chaps did a good job of keeping his legs from breaking into icy shards. He wasn’t sure if those duds helped keep the horse warmer, or if the black’s pumping blood stopped his legs from freezing. His socks and boots? He wasn’t sure they helped anything. He kept wiggling his toes to make sure they hadn’t frozen solid, but whether or not his toes actually moved, Colter couldn’t tell for certain.

Most likely, he’d find out when he dismounted.

He lifted his gaze toward the sky as he rode north, watching gray clouds darken, feeling the wind’s icy breath find openings to his body—also protected by his long-handle winter unmentionables—caused by his movement.

I could take this miserable cold, he lied to himself, if only it would snow.

To his right, his tracker, pardner, best friend, second father—whatever you wanted to call him—hacked up something nasty but didn’t spit it out. That would have frozen his bandanna to his lips. Jed Reno swallowed and said, “January. Forty-nine. You shoulda been here for that. Now, that winter was colder than a witch’s . . .”

Tim Colter’s muffled curse shut the old mountain man up. For a bit. For a moment, Colter regretted even speaking. His lips cracked. But at least they felt warm for a few seconds.

This was not January. This, by his calendar, was April. It was true that Tim Colter had lived in the American West for pushing thirty years now, in Wyoming Territory for five years, back when it was still parts of Utah, Idaho, and Dakota territories. Before that, he had called Oregon home. He had buried a wife, a daughter, and two sons near the Pacific Ocean. And it was true that, from what he remembered of Danville, Pennsylvania, it could get cold back there, too, even in spring. He and his folks had set out west in ’44. A boy grew up quickly in the wilds of the frontier. Especially after a wagon-train massacre left him an orphan. And becoming a lawman kept a man on the move. And moving, he remembered his father telling him, kept a man warm.

Well, he was moving now. Bundled up so that he resembled a grizzly bear more than a human being.

And he was still freezing.

The wind died down just long enough for Colter to hear Reno’s chuckling. Jed Reno had been a mentor to Colter, who had survived that wagon-train massacre when he was nothing more than a button kid. Reno had shown Colter how to survive in the wilderness of the 1840s. When Colter returned from Oregon years later, widowed and a lawman, Reno had saved his bacon again. Tim Colter owed that mountain man, who had to be in his seventies by now—he had seemed older than dirt back when Colter was just a kid—more than he could ever repay.

But sometimes . . . oftentimes . . . Jed Reno could be just as irritating as the mule the old-timer rode.

Colter made another mistake. As Reno’s laughter grew louder, Colter, feeling prickled and cold, drew in a deep breath, and that wasn’t the thing to do on a day like this. His lungs felt frozen. His chest ached. He wanted to scream.

Reno laughed again.

“Reckon that’s what happens when a feller gets a job where he spends most of his days in a comfy office, looking at papers, readin’, writin’ letters, telegraphin’ Washington City and Denver and checkin’ with the warden over at that prison in Laramie City. Forgettin’ ever’thin’ this ol’ hoss learnt you.”

Riding into the wind sure didn’t help, so Colter brought his gloved hand to the coverings over his nose, which he pinched and sniffed. He leaned back, stretching the muscles and hearing his back crack.

“See what I’m tellin’ you.” Reno went right on talking, as though he were gossiping with the old ladies at church—as if Jed Reno had ever set foot in a church—or waiting for his turn to get his hair and beard shorn by one of those tonsorial artists at Barrett’s place—as if Jed Reno had ever stepped inside a barbershop. “You ain’t been in a saddle in a dog’s age. Stretchin’ your legs underneath some desk in that fancy guvment buildin’. No, sir. You’s done forgots ever’thin’ I taught you back when you wasn’t so fat.”

Fat? Jed Reno was showing the paunch of an old man who couldn’t eat panther meat in the mountains anymore and work like a dog trapping, scouting, fishing, and hunting. Hunting wild game. Hunting wilder men.

Colter reined in the black.

Reno stopped a few yards ahead, turned in the saddle, and grinned.

“I hurt yer feelin’s?”

Colter’s head shook slowly.

The old man chuckled. “You sore from ridin’ so much? We ain’t hardly covered five miles yet.”

The eyes did not focus on the bear of a man, but stared off toward the rocks.

“Them train robbers be puttin’ some miles ahead of us.”

Still, Colter did not look Reno in the mountain man’s right eye. A black patch covered where the six-foot-four behemoth’s left eye used to be.

“You want to ride,” he said, “go ahead. But you’ll be breaking one of the rules you taught me almost thirty years ago.”

The old man’s expression changed, but he kept his good eye on Colter. Reno asked no question, just waited for Colter to say what was on his mind.

“Never ride into another man’s gunsights.”

Slowly, Reno’s head turned back and stared.

The wind blew harder, but the ground was so frozen and the trees so scarce, no dust blew. In fact, it was a clear day. Would have been pretty to some. Probably was, in fact. Might have been right pleasant if it weren’t so brutally cold.

Colter smiled as Reno slowly moved his Hawken rifle across his thighs.

“See it?” Colter asked.

Reno’s “Yeah” came out as a grunt.

Sunlight had peeked just enough between clouds to reflect off the metal in the rocks off to their left.

“What do you think?” Colter asked.

“Tough shot, uphill, with the wind blowin’ like it is. And we might be out of range, dependin’ on what kind of rifle that be.”

“If it is a rifle,” Colter said.

The mountain man’s head nodded again, just once. His rifle did not move. Reno’s mule snorted, stamped its forefeet, just to keep warmer.

Colter reached behind him, pulled open the flap of his saddlebag, and found the binoculars. Clouds swallowed the sun again, which was behind him, so there was not much of a chance that the lenses would give them away. Besides, if that was a rifle and it was trained on Colter and Reno, the ambusher already knew they were up here. He brought the spyglasses to his face, but only after thumbing off the front lenses with his gloved thumbs.

It took a while to find the spot, and he adjusted the focus, holding his breath to keep a fog from covering the lenses. Finally, he lowered the glasses and relaxed.

“Well?” Reno tried not to sound impatient.

“Looks like a long gun,” Colter said. “But there’s no one holding it.”

“Man don’t leave no rifle lyin’ round in this country,” Reno said.

A truer statement Colter hadn’t heard in a long spell.

“Unless he’s dead,” Colter agreed, and kicked his horse back into a walk.

“Or . . .” Reno let his mule follow Colter’s black. “It’s an ambush.”

Colter nodded. “Thought about that.”

“Yeah.”

“Figured you being bigger than me, you’d get shot first. I could dive off my horse.”

“You’d be afoot.”

“But I’d know where those ambushers were. And I’d still be alive.”

Reno chuckled.

Colter and Reno had been doing this for a long time now. Colter kept his eyes to the left and straight ahead, while Reno focused on straight ahead and to the right. Years of practice. Years of staying alive. They did not look behind them. They didn’t have to. They had scanned those places when they rode past, and, sure, there was a chance they might have missed something, someone. There was a possibility they had run into owlhoots who were better at this kind of game than they were.

But they hadn’t yet.

“I don’t think those dunderheads that held up the UP even slowed down,” Reno said after they had covered roughly one hundred yards.

Colter kept his focus on the rocks and the general area of the lone rifle. But he wasn’t about to second-guess his mentor.

Four men, wearing linen dusters and wheat sacks over their faces, had held up the 109 train at Simpson’s Well, about ten miles west of Cheyenne. It was an express run, no passengers, not much freight, and they had cold-cocked the man at the station, and one of them had brought out a red lantern and used that to stop the train. Otherwise, the 109 would not have stopped until reaching Laramie City.

So those owlhoots had some knowledge about trains. And they had made off with about $800 in bonds, cash, and coin. Not a bad haul. Almost like something the Reno Gang might have pulled off back east in Indiana. But this wasn’t the work of the Reno boys. Those outlaws had met their end at the end of handy ropes back in ’68.

And these Wyoming ruffians hadn’t been as smart as the Renos. They had gotten a good bit of money, but the express agent had fooled them, and they had missed the $65,000 in freshly minted coin.

Now Colter reined up. The high rocks blocked most of the wind, but they also blocked out most of the sunlight that crept through the clouds, so it felt colder.

He had not been mistaken. That was a rifle on the rocks. A Winchester Yellow Boy, which was why it had been so easy to spot; the bright gunmetal receiver gave the .44 repeating rifle its nickname, and the bronze-brass alloy sure came in handy at reflecting sunlight.

Reno’s mule snorted, and Colter heard him twist in the saddle.

Seeing the gloved hand and arm lying in a crevasse between one slab of rock and the flatter rock on which the Yellow Boy rested, the old trapper sighed, then cursed.

“I don’t think them owlhoots done this dirty deed,” Reno said, nodding at the horse tracks they had been following since Simpson’s Well.

Colter dismounted and walked toward his mentor, handing him the reins.

“Them hombres never even slowed down from a lope.”

That guess would get no argument from Tim Colter, who moved into the rocks. He saw the boot prints, and followed them easy enough, twisting toward the west and the higher slabs, then angling southeast, where he saw the man, face planted in a dip in the rocks, right arm reaching toward the rifle atop the rocks, left arm hanging down, knees in the dirt.

He wore a heavy mackinaw, worn boots, heavy woolen pants, and well-worn cavalry boots. No sign of a horse. And he wasn’t wearing spurs. But a man did not walk through this country.

The bullet hole was easy enough to spot. He had been shot in the back, down low, and blood had frozen against the checkered woolen coat.

Colter moved his right hand away from his powerful pistol. This hombre wasn’t a threat, so the lawman looked around. No, the train robbers had not shot him. They couldn’t have even seen him from where he was. And they had been riding so hard they had not seen any sunlight reflecting off the Yellow Boy—if the sun was shining.

He heard Reno dismounting. Colter moved toward the man, put his hand on the left shoulder, and turned him around.

The man’s groan took about two years off Colter’s life.

“Jed!” he yelled. “He isn’t dead.”

How a man could survive a bullet in his back and in this freezing wilderness would be one unsolved mystery, though the rocks would have blocked most of the wind, and Reno had heard of hot springs in this part of the country sometimes heating the ground.

Colter caught him, eased him onto the ground, letting the man’s big black hat serve as a pillow. He pulled back the man’s coat, which was unbuttoned, and saw no sign of an exit wound. The bullet was still in him.

Using his teeth to pull off the right-hand glove, Colter then pressed his finger and thumb against the man’s throat. The face was pale. The pulse was slow. Too slow.

Reno’s big feet pounded and the old man wheezed as he came behind Colter. He had brought his bedroll with him and used that to cover the man.

“Ever seen him?” Reno asked, and reached for the Winchester .44.

“No.” Colter looked at the man’s duds, but they held no significance. He studied the face again. Mustache. Beard stubble. The outfit like what he had seen countless times.

“Me neither.” Reno coughed slightly, turned, and spat. “Don’t see no sign of a horse. Looks like he just dropped here.”

No, he didn’t just drop here. Colter figured he was hiding here. Reno was right about the lack of boot prints, and that frontiersman might have been long in tooth and gray in hair, however, his right eye was still sharp enough to have found even a moccasin track or signs where the tracks had been brushed away. But Colter had an idea.

“He was hiding.”

“To ambush someone maybe?”

“I don’t think so,” Colter said. “But my guess is . . .” He pointed toward the rocks on the northwest side. “The man who gunned him down came up on the rocks. This guy was keeping an eye that-away.” He pointed toward the trail, not the way to Cheyenne, but off to the north. “They sent someone ahead, on the other side of this ridge.”

“He had to be a quiet hombre.”

“Yeah.”

Reno coughed. “We got to get him to a doctor.”

“No.”

Both men turned toward the stranger.

His eyes had opened. They couldn’t quite focus. A bit of blood spilled out of the corner of his mouth. He coughed, groaned, and breathed in deeply, but that was a ragged, ghastly sound, and Colter figured the bullet was in one of his lungs.

“I’m . . . done . . . for. . . .”

Suddenly, the man’s left hand reached out and grabbed Colter’s coat. He jerked, but he didn’t have enough strength, and Tim Colter was too strong. The hand slipped away and fell onto the dirt.

“You . . .” the man whispered. “Stop them. . . .” He coughed again, and this time spat out bloody phlegm.

“My name is Tim Colter.” He unbuttoned the coat, pulled it back to reveal the tin badge pinned to his vest. “I’m a deputy US marshal out of Cheyenne.”

The man’s face brightened for just a second.

“Gooooood.”

“Who shot you? Who are you? What happened?”

“Secret,” the man said. “Service.”

Colter thought he must have heard wrong. He leaned closer, and now he felt dread, cold, and fear. The light was leaving the man’s eyes.

“President Grant . . . assassination . . . Dugan . . . trust nobody.”

The last breath came short and permanent. The eyes stilled.

Colter’s heart pounded. He kept hoping, praying, that the man would revive. He needed a Lazarus. He wanted a miracle. But the man just stared into another world.

And Tim Colter felt much colder than he had since he had ridden out of Cheyenne into this freezing country.

“Reckon we can cover’m with some sand and rocks. Keep the wolves off’m.” Jed Reno nodded in approval of his suggestion. “That’ll keep’m, maybe, till we catch up with ’em owlhoots.”

Tim Colter was not aware that he was shaking his head and didn’t even hear him say, “No.”

“Well, I ain’t partial to leavin’ any man to the buzzards. Even the most rottenest scoundrel deserves that, I reckon.”

Colter faced Reno. “We’ll bury him.” He squatted by the body and began going through the pockets, searching for some identification: a letter, maybe; a watch inscribed with his name; initials on his belt; a money purse . . . anything.

“Ground’s froze perty good,” Reno said. “Even a shallow grave will take considerable time and effort. And those train robbers is putting some distance betwixt us as we palaver over this.”

“Let them go,” Colter said and pulled out a few dollars from the corpse’s shirt pocket.

“Let ’em go?” Reno thundered. “Ain’t like you to let train robbers get off scot-free.”

“Shut up, Jed,” Colter said, “and scout around. See if you can find any sign, anything this man might have left, hidden, dropped. Anything.”

He didn’t recollect that rebuke until much later, and when he heard the mountain man’s soft footsteps as he gathered the reins to their mounts, tethering them to a good-size stone in a grassy spot, he said, “I need your best work here. Look hard. I don’t know exactly what you ought to look for. But if you see something that doesn’t fit in this country, get it and bring it to me. On the double.”

The hat held nothing. No name written on the sweatband inside the crown and nothing tucked behind the band, but it was a cheap hat, well-used, ancient, the kind a man could buy in a mercantile for ten bits. Colter unfolded his knife and cut away the linings in the coat he removed from the dead man to unearth the same results. Nothing. The shirt was pocketless, and the man wore no locket, nothing like that, and the heavy flannel undershirt revealed only blood from the fatal bullet.

He didn’t think the assassin, or assassins, had searched the body as he had. If they thought he had something of value, something they did not want anyone else to happen by, they wouldn’t have left the man alive. He was surprised they hadn’t made sure he was dead.

Sloppy work for killers. And lucky for Tim Colter.

The boots were harder to pull off, and the worn socks came off with them, and still Colter found nothing. He sighed. He even felt flushed with heat, though the temperature had to be dropping as the sun continued its ongoing descent behind the high hills and mountains.

His horse whinnied, and Colter found the LeMat he still favored, even though it was pushing eighteen years old and more modern sidearms were available these days. Even Jed Reno packed a .45-caliber Colt, though he preferred his Hawken rifle. But a revolver, good as it was, held only six rounds in the cylinder, and most practical gunmen kept only five beans in the wheel, as the saying went. The LeMat’s cylinder held nine .42-caliber cartridges, and just in case Colter needed something extra, there was a smoothbore secondary barrel of .63 caliber that could send a blast of grapeshot into a bad man’s face or belly.

He didn’t slip that monster from the leather because Jed Reno eased his dark mule into view. He dismounted with a grunt, and Colter went back to work on the dead man’s boots.

Which stopped Reno cold when he made it through the path.

Colter glanced up, saw the look on his old mentor’s face, and realized just how ridiculous he looked, holding the boots of a dead man that had been stripped to his undergarments.

“Taken an Injun’s scalp in my day,” Reno said. “Taken pelts, maybe a chaw of baccy, a pistol. Don’t recall ever doin’ nothin’ like that, especially considerin’ how worn-out his duds are. And them boots ain’t gonna fit you or me.”

Colter focused on the boots, running his left hand inside the first one he had removed.

“You find anything?” he asked.

“Tracks. Four horses . . .”

He worked on the heel, hoping to find some secret compartment, and when that failed he moved to the other boot, but he listened as Reno gave his report.

“My guess is they rid ahead. Waited for him. The way I read the sign, what sign there was, ’pears to me that one of ’em scoundrels climbed up the rocks. Found hisself a perch. And waited. Two riders rode back thataway. The fourth one waited with the hosses, smoked hisself some baccy.”

There was nothing in this boot either. Colter tried the heel.

Reno pointed north. “There’s a cut in the hills about two–three miles up yonder way. I would suspect that the two riders went back there, and I would guess that they had left another rider, maybe more, to make sure that dead man didn’t take a detour through that place, though it ain’t no easy squeeze for even a sliver of a fellow like this one to get through. But there’s a good elk trail that leads to the top, and on the other side, if you been in this country as long as I have, you know how you can get down this side of it.”

Colter gave up on the boot and stifled a curse.

Reno stared and Colter met his gaze.

“So they waited for him to pass. Then rode after him.”

The big man’s head bobbed.

“This feller, he hears the hoofbeats behind him. Gots to hide, he figgers. So finds hisself a hidin’ place. Waited. But didn’t know there was a man with a big rifle aimin’ to kill him from behind.”

Colter considered that. “Lot of trouble. Why not just ride him down if he was afoot?”

“I don’t reckon he was always afoot. Not out here.”

Quickly grabbing the closest boot, Colter saw the marks of spurs.

Reno read his mind. “Shucked the spurs when he lost his horse. Spurs make noise. He wanted to be quiet. And spurs ain’t good fer runnin’ afoot.”

Colter dropped the boot. “So when he heard the horses coming after him, he ran into these rocks. Hid. Hoping for the best.”

“And these be the best rocks for hidin’ in this here patch of paradise,” Reno said. “A man with a bit of savvy can hide hisself good and hide hisself for a long time.” He nodded at the dead man. “He was savvy. Give him that. Just got hisself outsavvied.”

Turning back toward the dead man, Colter shook his head and sighed. “He outsavvied me.”

“Mebbe so. But now do you mind tellin’ me just what in the Sam Hill is goin’ on? What that man told you, ’bout Grant and Dugan and asinine—”

“Assassination,” Colter corrected.

“Right. Grant I know. Fella paid me a dollar and a bottle of real rye whiskey to vote for him in that election last year. Voted for him twice.”

“So you voted for him in ’68, too?” Colter would not have guessed Jed Reno had voted in any election, local, territorial, or national.

“Nah. Last year. Man said, no, this country wouldn’t last on no Greeley-Brown ticket. He blamed Greeley for foulin’ up the Western country, gettin’ all these Eastern folks, and foreigners now, claimin’ homesteads and the like. I thought he had somethin’ there, and then he showed me that dollar coin and that bottle of rye whiskey. So after me and some other gents he had found eager to vote, we went to vote in Cheyenne. Then he paid our way to Laramie City and we voted there, too. Free train rides there—though he tricked us because we had to sneak aboard an eastbound to get back home. But I reckon it paid off for him. Grant got voted into office. Figured my vote might have been the one that won it all for him.”

“Your two votes.” Colter had wasted enough time. He looked at the body, sighed, and whispered, “Who are you?”

Reno walked closer. “You ain’t tol’ me what this deal is, sonny. Man like me might come to think that you don’t trust me a whole lot.”

“That’s not it, Jed,” Colter said, shaking his head. “It’s just . . .”

Colter let out a sigh. Jed Reno just stared, but then his surviving eye shifted, that bearded countenance changing suddenly. Looking at the dead man, the old trapper raised his hand and pointed.

“What,” he said, “in tarnation is on the bottom of that feller’s foot?”

Kip Jansen didn’t like Wyoming Territory, which was absolutely nothing like the rolling green hills, fine fields for growing food crops—not tobacco, not cotton—but crops that didn’t need slaves or sharecroppers but were small enough to feed a family, and the lush, fine forests of Alabama. He didn’t want to be here. He hated the cold weather. Sure, it got cold sometimes in Morgan County, but he never had felt anything like this. That brutal wind just never wanted to let up, and he had always liked the pretty white snow on those few winter days when it would snow back home. But this snow wasn’t pretty and, like the wind, it kept coming and coming and coming. Relentless.

He missed the forests. Longed to be back on that small farm. Yearned for the bustle of carriages and farm wagons and friendly girls and boys of Decatur. Or the scream of a railroad locomotive’s whistle. He pined for the Tennessee River and the steamboats that traveled up and down it. He hadn’t seen anything resembling a river in Wyoming Territory, or practically anywhere in the West since the muddy Missouri. What a Westerner called a river in Wyoming would have been laughed at back home in Alabama and called, maybe, a creek.

Being here was his stepfather’s doing. Kip hated that trashy-mouthed man more than he despised Wyoming. Lige Kerns was lazy, mean, and ignorant. What his mother saw in him boggled Kip’s fourteen-year-old brain.

But mostly, Kip Jansen despised his stepfather because Lige Kerns fought for the Confederacy during the late War Between the States. Well, most of the menfolk in Alabama had worn the gray. But not so much in Morgan County, and a few other spots in northern Alabama. Plenty of men in Morgan County despised the idea of secession, of fighting a war. There were slaves in Decatur, and in Morgan County—more than a few—but war, Kip remembered his father saying, was a drastic, desperate, and despicable measure when negotiations and compromise could be used peacefully.

When the war heated up, Kip’s father put on a Yankee uniform. And because of. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...