- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

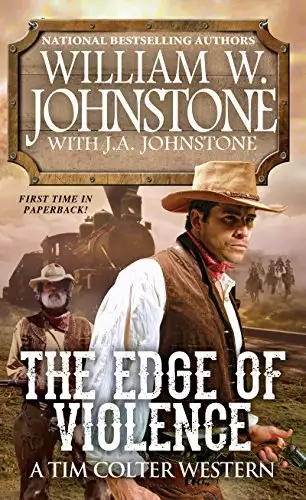

THE GREATEST WESTERN WRITERS OF THE 21ST CENTURY

Bestselling authors William and J.A. Johnstone continue the wild, epic saga of Tim Colter with the building of the transcontinental railroad—and the making of the American Dream . . .

Twenty-two years have passed since Tim Colter and his family were ambushed on the Oregon Trail, forcing the young boy to find an unlikely ally in one-eyed mountain man Jed Reno. Now a widowed deputy U.S. marshal and Civil War veteran, Colter is finally ready to remarry and settle down—until a dangerous new assignment becomes a life-or-death struggle for the soul of a town and the heart of its people . . .

The Union Pacific Railroad is laying down tracks connecting the great northwest to the rest of the country. But two rival factions have set their sights on the town of Violet—aka Violence—to gain control of the rails. It's Colter's job to tame the rampant greed and rising tensions. But to do it, he'll need to deputize his trusted old friend Jed Reno—and wage a savage new war that will determine the fate of the Dakota Territory and the future of a nation.

Bestselling authors William and J.A. Johnstone continue the wild, epic saga of Tim Colter with the building of the transcontinental railroad—and the making of the American Dream . . .

Twenty-two years have passed since Tim Colter and his family were ambushed on the Oregon Trail, forcing the young boy to find an unlikely ally in one-eyed mountain man Jed Reno. Now a widowed deputy U.S. marshal and Civil War veteran, Colter is finally ready to remarry and settle down—until a dangerous new assignment becomes a life-or-death struggle for the soul of a town and the heart of its people . . .

The Union Pacific Railroad is laying down tracks connecting the great northwest to the rest of the country. But two rival factions have set their sights on the town of Violet—aka Violence—to gain control of the rails. It's Colter's job to tame the rampant greed and rising tensions. But to do it, he'll need to deputize his trusted old friend Jed Reno—and wage a savage new war that will determine the fate of the Dakota Territory and the future of a nation.

Release date: September 26, 2017

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 284

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

The Edge of Violence

William W. Johnstone

Decades ago—by Jupiter, a lifetime, an eternity—Jed Reno had laughed at Jim Bridger. When the old (by mountain-man standards) fur trapper, scout, and guide had teamed up with Louis Vasquez to build a trading post on the Blacks Fork of the Green River, Jed Reno had jokingly told Bridger that Bridger’s nerves had finally frayed. That Bridger was selling out. That he was calling it quits. That, pushing forty years old, he was too long in the tooth to be traipsing over the Rocky Mountains, trapping beaver and fighting the weather, the wilds, and the Indians. While sharing a jug of Taos Lightning or some other forty-rod whiskey seasoned with snakeheads, tobacco, and strychnine, Reno had slapped Bridger on the back, and told him, “Well, you just enjoy your life of leisure. I’m sure you’ll be richer than a St. Louis whiskey drummer with this here venture of yours.”

“Runnin’ a store, ol’ hoss,” Bridger had told him, “ain’t as easy as you think it is.”

“Balderdash,” Reno had said.

Damnation, if Jim Bridger wasn’t right.

As a bullet blew apart the copper-lined tin corn boiler, Reno ducked beneath the somersaulting axe handle that smashed the shelves behind him, sending metal-backed mirrors, salt and pepper shakers, scissors, axe blades, lanterns, baskets, jugs, matches, soaps, knives, forks, beads, containers of linseed oil, pine tar, and tins of tobacco flying every which way. He landed on the pile of pillow-ticking fabric and the woolen blankets he had not gotten around to stacking on the shelves, and he had to be thankful for that. At seventy years old, or something like that (Reno kept bragging that he had stopped counting after fifty) , the onetime fur trapper wasn’t as game as he used to be.

Which is why he had followed in Bridger’s footsteps, and set up his own trading post about a dozen or so years ago on Clear Creek.

“You done a smart thing,” Bridger had told him. “Make some money. Watch people go by. Drink whiskey. Smoke yer pipe. Easy livin’.”

A hatchet fell with the axe handle, and the blade almost cut off Reno’s left ear. A brass percussion capper bounced off his eyebrow. His good eye. An inch lower, and Jed Reno figured he might be wearing leather patches over both eyes.

Easy livin’? A body could get killed running a store.

He heard boots thudding across the packed earthen floor. His left hand reached up, found the handle to the hatchet that had almost split his head open, and jerked it free from the blankets and bolts of pillow ticking just as the bearded figure appeared on the other side of the counter.

A big man, bigger than even Reno, wearing fringed buckskin britches, black boots like those a dragoon or horse soldier might be wearing, collarless shirt of hunter green poplin, garnet waistcoat, and a battered black hat, flat-brimmed and flat-crowned. He also wore a brace of flintlock pistols in a yellow sash around his belly. One of those pistols was in his right hand.

Reno saw the hammer strike forward just as he flung the hatchet. Powder flashed in the pistol’s pan, the barrel belched flame and smoke, and a .54-caliber lead ball embedded itself in the brown trade blanket rolled up on Reno’s right.

“Horatio!” a voice yelled. Reno could just make out the voice as he sprang up, fell forward, and crawled toward the soon-to-be-dead Horatio, whose only replies were gurgles as he lay on his back as blood spurted from his neck like water from an artesian well.

The voice swore, and then barked at the third man who had entered Reno’s trading post: “Sam, he’s goin’ fer Horatio’s pistols. Get’m. Quick.”

This time, Jed Reno heard clearly. The ringing from Horatio’s pistol shot had died in Reno’s ears. He dived the last couple of feet, ignoring the lake of blood that was ruining toothbrushes and staining wrapped bars of soap and the beads a Shoshone woman kept bringing him to trade for pork and flour, which, in turn, Reno sold to wayfarers from New York and Pennsylvania and Ohio and even Massachusetts who had been traveling so far that many of the ladies thought those beads from Prussia or someplace were prettier than rubies and garnets.

Reno jerked the second pistol from the dead man’s sash. Horatio, Reno knew, was dead now because the blood no longer pulsed, but merely coagulated. Footsteps pounded, but not only coming from Sam’s direction. The Voice was charging, too, and Jed Reno had only one shot in the flintlock he had jerked from Horatio’s body. His left hand gripped the butt of the .54 Horatio had fired just moments before.

Sam appeared on the other side of the counter, where Reno had been refilling a barrel with pickled pig’s feet when the three men entered his store.

Sam was the oldest of the rogues, with silver hair, a coonskin cap, and dark-colored, drop-front broadfall britches—which must have gone out of fashion back when Reno was a boy in Bowling Green, Kentucky—muslin shirt, red stockings, and ugly shoes. A man would have guessed him to be a schoolmaster or some dandy if not for the double-barrel shotgun he held at his hips.

The flintlock bucked in Reno’s right hand, and just before the eruption of white smoke obscured Reno’s vision, he saw the shocked look on Sam’s face as the bullet hit him plumb center, just below his rib cage. With a gasp, Sam instantly pitched backward as if his feet had slipped on one of the bar-pullers, tompions, nuts, bolts, and vent and nipple picks that lay scattered on the floor. He touched off both barrels of the shotgun.

One barrel had been loaded with buckshot, the other with birdshot—as if he had been going out hunting for either deer or quail—and the blast blew a hole through the sod roof, and dirt and grass and at least one mouse began pouring through the opening, dirtying and eventually covering the ugly city shoes the now-dead Sam wore on his feet.

Reno rolled over, just as The Voice leaped onto the top of the counter. The pistol in Reno’s left hand—the one he had jerked off the floor near the blood-soaked corpse of Horatio—sailed and struck The Voice in his nose. Reno caught only a glimpse of the revolving pistol The Voice held, because as soon as the flintlock crashed against the bandit’s face, blood was spurting, The Voice was cursing, and then he was disappearing, crashing against the floor on the other side of the counter. Reno came up, hurdled the counter, and caught an axe handle on his ankles.

This time, Reno cursed, hit the floor hard, and rolled over, but not fast enough, for The Voice jumped on top of him and locked both hands around Jed Reno’s throat.

Now that he had a close look at the gent, The Voice had more than just a rich baritone.

He had the look of a man-killer. Scars pockmarked his bronzed face, clean-shaven except for long Dundreary whiskers, and his eyes were a pale, lifeless blue. Those eyes bulged, and the man ground his tobacco-stained teeth. The nose had been busted two or three times, including just seconds ago by Horatio’s empty .54-caliber pistol. Blood poured from both nostrils and the gash on the nose’s bridge. One of The Voice’s earlobes was missing—as if it had been bitten off in a fight. He seemed a wiry man, all sinew, no fat, and his hands were rock-hard, the fingers like iron, clasping, pushing down against his throat, and cutting off any air.

He wore short moccasins, high-waisted britches of blue canvas with pewter buttons for suspenders that he did not don; a red-checked flannel shirt that was mostly covered by the double-breasted sailor’s jacket with two rows of brass buttons on the front and three on the cuffs. The black top hat The Voice had worn had fallen off at some point during the scuffle.

But he was a little man, no taller than five-two, and a stiff wind—which was predictably normal in this country—would likely blow him over.

Jed Reno figured he was forty years older than The Voice, but he had more than a foot on the murdering cuss, and probably seventy pounds. Jed kept rolling over, and The Voice rolled with him. They rolled like the pickle barrel Sam had knocked over with his right arm as he fell to the floor in a heap and ruined the store’s roof. Rolled against an overturned keg of nails and knocked over the brooms until they hit the spare wagon wheels leaning against the wall.

The Voice came up, pushing off one wagon wheel, then flinging another at Reno, who blocked it with his forearm, and sat up, slid over, and leaped to his feet.

Staggering back toward the sacks of flour, beans, and coffee, The Voice wiped his mouth. The lower lip had been split. Reno tasted blood on his lips, but he didn’t know if it belonged to him, The Voice, or the late Horatio.

“You one-eyed bastard.” The Voice had lost much of its musical tone. More of a wheeze. But the little man was game.

He jerked a bowie knife that must have been sheathed behind his back. The blade slashed out, but Reno leaped back. Again. The Voice was driving him, until Reno found himself against another counter.

The Voice’s lips stretched into a gruesome, bloody smile.

The knife’s massive, razor-sharp blade ripped through the flannel shirt; and had Reno not sucked in his stomach, he would be bleeding more than The Voice about this time. The blade began slashing back, but Reno had found the chains—those he sold to emigrants for their wagon boxes—and slashed one like a blacksnake whip. Somehow, it caught The Voice’s arm between wrist and elbow, and The Voice wailed as the bones in the arm snapped, and the big knife thudded on the floor.

As The Voice staggered back, Reno felt the chain slip from his hand. He was tuckered out, too, and, well, it had been several moons since he had engaged in a tussle like this one.

The chain rattled as it fell to the floor, and The Voice turned and ran for the door.

Sucking in air, Reno charged, lowered his head and shoulder, and slammed into the thin man’s side. They went through the open doorway, over what passed as a porch, and smashed through the pole where the bandits had tied their horses. Those geldings whinnied, reared, whined, and pounded at the two men’s bodies. One, a black gelding, pulled loose the rest of the smashed piece of pine and galloped toward the creek. One fell in the dirt, rolled over, came up—and ran north, leaving its reins in the dirt and wrapped around the broken pole. The other backed up, reared, fell over, and came up. Reno couldn’t tell which way he ran.

He was on his knees, spitting out dirt and blood, while wiping his eyes. He tried to stand, to find The Voice, when he tasted dirt and leather and sinew and felt his head snap back. Down he went, realizing that The Voice had kicked him. He landed, rolled, was trying to come up, when The Voice turned his body into a missile. His head caught Reno right in the stomach. Breath left his lungs. He caught a glimpse of the cabin he called a store flash past him as he was driven into the column that held up the covering over the porch.

The railing snapped. The covering collapsed, spilling more earth, debris, two rats, and a bird’s nest. The two men kept moving. Past the cabin. Over dried horse apples. A fist caught Reno in the jaw. Then another. The Voice packed a wallop. Reno brought up his arms in a defensive maneuver, leaving his midsection open. A fist—it had to be The Voice’s left, for his right arm was busted—hit twice. Three times. Reno fell against the woodpile, rolled over, hit the chopping block, and wondered if he had just busted a couple of ribs.

“Son of a bitch!” The Voice roared.

Reno blinked away sweat, blood, dirt, and dust. He saw the bandit standing next to the pile of firewood. He had a sizable chunk of wood in his left hand and, stepping forward, raised the club over his head.

Reno found the axe buried in the chopping block. Jerking it free, he flung it as he dived out of the way of the descending piece of wood.

He lay there, panting, played out, wondering why the devil The Voice didn’t just finish him off. But that instant of defeatism vanished quickly. Reno rolled over, came up, and spit. He looked left, and then right, and saw his cabin, saw the woodpile, and finally his eyes focused on the moccasins and the ends of the blue pants on the dirt.

Neither the feet nor the legs were moving.

Wiping the blood and grime from his face, Reno limped to the pile. He had to lean against the wood for support, and breathing heavily, he looked down at The Voice, and the axe, and the blood.

“You . . . horse’s . . . arse . . .” Jed Reno wheezed, and made a painful gesture at what remained of his trading post. “All three . . . of you . . . curs . . . dead . . . burnin’in . . . Hell.... Means . . . I gotta . . . clean this . . . mess . . . up . . . myself.”

Jed Reno salvaged what he could from the three dead men. The guns he could resell, even the two flintlock pistols, a matched set of A. Waters pistols with walnut grips—antiquated as they were. Reno also found a nice key-wind watch, and wondered who the dead man stole that from, but decided that the odds highly unfavored the victim—if the victim hadn’t been murdered—coming into Reno’s store and seeing his watch for sale. The boots and shoes might bring a bit of a profit, or he could trade them to the Shoshone woman for some more beads, along with the hats. Not much use with the clothes, especially now that they were all pretty much hardened and stained with dried blood. Reno was lucky. He even found a few gold coins and some silver in the outlaws’ pockets. He was alive, and figured he had made a pretty good trade with the three dead men.

It was shaping up to be one passable, profitable day. But Reno certainly didn’t look forward to cleaning up the mess.

He loaded the corpses onto his pack mule, saddled his bay gelding, and led his cargo away from the post, crossing the tracks of the iron horse. He looked east at the town, still mostly tents, although a few sod houses and frame buildings had been put up. Then he looked west, following the iron rails and wooden crossties laid by the Irishmen working for the Union Pacific Railway. He could see black smoke puffing out of the stacks of a locomotive down the line. Back east, he heard the screeching and ugly hissing and saw more black smoke as another train made its way through the settlement, hauling more spikes, rails, crossties, fishplates, sledgehammers, and maybe even a few more workers.

It was a big undertaking, the transcontinental railroad, and as much as Jed Reno despised the damned thing, he had to admit it was progress. And had made him fairly wealthy.

He rode about five miles north, decided that was good enough, and dumped the bodies into an arroyo. Buzzards had to eat. So did coyotes. And one thing Jed Reno did not like about that railroad was the fact that since they had started laying track across this part of the territory, most of the game had left the country.

Reno could remember talking with Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, and other trappers. It hadn’t been at one of the rendezvous because, the best Reno recalled things, those gatherings had ended by then. Maybe it had been at Fort Bridger. Talk had reached Bridger’s trading post about a railroad being planned, one that would stretch across the country. Carson had shrugged. Bridger had allowed it was true. Reno had laughed and called it a fool’s folly.

“How you gonna get one of them trains across these Rockies?”

“Don’t underestimate man’s ingenuity,” Bridger had said.

“Where, by thunder,” Carson had said, “did you pick up that ‘in-gen-yoo-ah-tee’ word?”

“And in winter?” Reno had said. “Can’t be done.”

Of course, a few years earlier, Reno would never have thought he would be seeing prairie schooners by the hundreds crossing the Great Plains and then across the mountains, bringing settlers from New York and Pennsylvania and other places foreign to a man like Reno, bound for the Oregon country and later California. Farmers. Merchants. Women and children and even milch cows and dogs. One gent had been hauling sapling fruit trees to start some orchards in the Willamette Valley.

Born in 1796 in what was now Bowling Green, Kentucky, Jed Reno had seen much in his day. His father then apprenticed Reno to a wheelwright up in Louisville, and Reno took that for longer than he had any right to before he stowed away on a steamboat and went down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. New Madrid. Then St. Louis. And then he signed up with William Henry Ashley and set out up the Missouri River and became a fur trapper. That had been the life, maybe the best years Reno would ever live to see, but . . . well . . . nothing lasts forever. Beavers went out of fashion. Silk became favorable for hats. Now fur felt had become popular. By Jupiter, Reno had a hat of fur felt on his head now, too.

So when Reno happened upon some men who said they were surveyors, and when they paid him gold to do their hunting and scouting for them, Reno decided that Jim Bridger was a pretty wise gent after all.

Reno had only one eye, but few things escaped his vision, and he had two good ears. And to live in the wilds of the Rockies and Plains since 1822, you had to see, and you had to hear. Reno listened to the surveyors. And he watched.

Apparently, there were a number of surveys going on. A couple were down south, which made a lot of sense to Reno. Weather would be warmer, less hostile, across Texas and that desert country the United States had claimed after that set-to with Mexico. Another up north, somewhere between the forty-seventh and forty-ninth parallels north—whatever that meant. Reno wasn’t sure England would care too much for that. Seemed to Reno that ownership of all that country up north was being debated between the king—or was it a queen now?—and whoever was president of these United States.

But the surveyors kept talking about a war brewing between the states. It had something to do with freeing the slaves or, to hear one of the men who spoke with a Mississippi drawl, it had to do with “a bunch of damn Yankees pushing us good Southern folk around.” That got Reno to figuring that there was no way the United States would put up a railroad across country that might not be part of the United States in a few years. So he paid even closer attention to the surveyors.

Around 1853, some surveyors had been hauling their boxes and making their maps along what most folks called the Buffalo Trail, led by some captain named Gunnison. Something the surveyors called the Thirty-fifth Parallel Route. Reno figured that one died when Ute Indians killed some of the soldier boys, but he also met another one of those young whippersnappers who called himself an engineer. Went by the name of Lander, Frederick W. Lander, who worked for some outfit called the Eastern Railroad of Massachusetts. Lander told Reno that there could never be a railroad in the South, but a railroad had to connect the Pacific with the Atlantic because if war came—not among the states, but against a European power with a strong navy and mighty army—the United States would not be able to defend California without “an adequate mode of transit,” whatever that meant.

So Reno decided to throw up a trading post along Clear Creek in the Unorganized Territory, take a gamble that Lander was right, and that eventually he’d be selling items to greenhorns stopping for a rest on this transcontinental railroad.

The post was a combination of logs—which he had hauled down from the Medicine Bow country—and dirt. He had built it into a knoll that rose near the creek, digging out a cave that he knew would be cool enough in the summer and hot enough in the winter. The logs stuck out and made the post look more like a cabin, though, and gave it more of an inviting feel. Reno had never cared much for those strictly sod huts that looked, to him, like graves. This way, part log cabin, the post didn’t seem completely like a grave to Jed Reno.

A few years later, Lander came back again, and this time he had some painter guy with him. That’s when Jed Reno began feeling pretty confident about his investment. After all, if you hired some artist to paint some pretty pictures of you working, then you had to think that this was being documented for history.

Besides, even if it didn’t happen, if the railroad went north or south or never at all, well, Jed Reno still had a place he could call home, that would keep him warm in the winter and cool in the summer. He had a good source of water, and could fish or hunt or get drunk or just sit on his porch—if you could call it a porch—and watch the sun rise, the sun set, the moon rise, the moon set. By Jupiter, he was pretty much retired anyhow, like ol’ Bridger.

Of course, the war came—just like everyone had been talking about—and the surveyors and engineers stopped coming. Poor young Frederick Lander. He joined up to fight to preserve the Union, and from the stories Reno heard, the boy took sick with congestion of the brain and died somewhere in Virginia in 1862. Wasn’t even shot or stuck with one of those long knives or blown apart by a cannonball. Reno wondered if that gent with the paintbrushes—some gent named Albert Bierstadt, who had dark hair, a pointed beard, and penetrating eyes—ever amounted to much.

Most of the blood inside the trading post had been covered with more dirt, which Reno packed down with his moccasins. The merchandise that had been busted, or soaked or stained with blood, he tossed into a canvas bag and hauled to the smelly dump that the settlers, who had not moved on with the railroad, had started up and was already attracting vultures and rats and coyotes and flies. But it was far enough away from Reno’s post that the smell seldom bothered him too much.

He salvaged most of the merchandise, not that it really mattered. Since the railroad had moved on, Reno had not seen much business, and since the trains brought only supplies and more workers, it wasn’t like settlers were stopping to spend money on trinkets and blankets and tin cups. Reno began to doubt if he could ever sell anything else—not that he really cared one way or the other.

Fixing the hitching rail was probably the easiest thing, since he had hammers and plenty of nails and even some spare ridgepoles, located behind the post, he could use. The roof and the porch, however, were another matter. He had to use another pole. . .

“Runnin’ a store, ol’ hoss,” Bridger had told him, “ain’t as easy as you think it is.”

“Balderdash,” Reno had said.

Damnation, if Jim Bridger wasn’t right.

As a bullet blew apart the copper-lined tin corn boiler, Reno ducked beneath the somersaulting axe handle that smashed the shelves behind him, sending metal-backed mirrors, salt and pepper shakers, scissors, axe blades, lanterns, baskets, jugs, matches, soaps, knives, forks, beads, containers of linseed oil, pine tar, and tins of tobacco flying every which way. He landed on the pile of pillow-ticking fabric and the woolen blankets he had not gotten around to stacking on the shelves, and he had to be thankful for that. At seventy years old, or something like that (Reno kept bragging that he had stopped counting after fifty) , the onetime fur trapper wasn’t as game as he used to be.

Which is why he had followed in Bridger’s footsteps, and set up his own trading post about a dozen or so years ago on Clear Creek.

“You done a smart thing,” Bridger had told him. “Make some money. Watch people go by. Drink whiskey. Smoke yer pipe. Easy livin’.”

A hatchet fell with the axe handle, and the blade almost cut off Reno’s left ear. A brass percussion capper bounced off his eyebrow. His good eye. An inch lower, and Jed Reno figured he might be wearing leather patches over both eyes.

Easy livin’? A body could get killed running a store.

He heard boots thudding across the packed earthen floor. His left hand reached up, found the handle to the hatchet that had almost split his head open, and jerked it free from the blankets and bolts of pillow ticking just as the bearded figure appeared on the other side of the counter.

A big man, bigger than even Reno, wearing fringed buckskin britches, black boots like those a dragoon or horse soldier might be wearing, collarless shirt of hunter green poplin, garnet waistcoat, and a battered black hat, flat-brimmed and flat-crowned. He also wore a brace of flintlock pistols in a yellow sash around his belly. One of those pistols was in his right hand.

Reno saw the hammer strike forward just as he flung the hatchet. Powder flashed in the pistol’s pan, the barrel belched flame and smoke, and a .54-caliber lead ball embedded itself in the brown trade blanket rolled up on Reno’s right.

“Horatio!” a voice yelled. Reno could just make out the voice as he sprang up, fell forward, and crawled toward the soon-to-be-dead Horatio, whose only replies were gurgles as he lay on his back as blood spurted from his neck like water from an artesian well.

The voice swore, and then barked at the third man who had entered Reno’s trading post: “Sam, he’s goin’ fer Horatio’s pistols. Get’m. Quick.”

This time, Jed Reno heard clearly. The ringing from Horatio’s pistol shot had died in Reno’s ears. He dived the last couple of feet, ignoring the lake of blood that was ruining toothbrushes and staining wrapped bars of soap and the beads a Shoshone woman kept bringing him to trade for pork and flour, which, in turn, Reno sold to wayfarers from New York and Pennsylvania and Ohio and even Massachusetts who had been traveling so far that many of the ladies thought those beads from Prussia or someplace were prettier than rubies and garnets.

Reno jerked the second pistol from the dead man’s sash. Horatio, Reno knew, was dead now because the blood no longer pulsed, but merely coagulated. Footsteps pounded, but not only coming from Sam’s direction. The Voice was charging, too, and Jed Reno had only one shot in the flintlock he had jerked from Horatio’s body. His left hand gripped the butt of the .54 Horatio had fired just moments before.

Sam appeared on the other side of the counter, where Reno had been refilling a barrel with pickled pig’s feet when the three men entered his store.

Sam was the oldest of the rogues, with silver hair, a coonskin cap, and dark-colored, drop-front broadfall britches—which must have gone out of fashion back when Reno was a boy in Bowling Green, Kentucky—muslin shirt, red stockings, and ugly shoes. A man would have guessed him to be a schoolmaster or some dandy if not for the double-barrel shotgun he held at his hips.

The flintlock bucked in Reno’s right hand, and just before the eruption of white smoke obscured Reno’s vision, he saw the shocked look on Sam’s face as the bullet hit him plumb center, just below his rib cage. With a gasp, Sam instantly pitched backward as if his feet had slipped on one of the bar-pullers, tompions, nuts, bolts, and vent and nipple picks that lay scattered on the floor. He touched off both barrels of the shotgun.

One barrel had been loaded with buckshot, the other with birdshot—as if he had been going out hunting for either deer or quail—and the blast blew a hole through the sod roof, and dirt and grass and at least one mouse began pouring through the opening, dirtying and eventually covering the ugly city shoes the now-dead Sam wore on his feet.

Reno rolled over, just as The Voice leaped onto the top of the counter. The pistol in Reno’s left hand—the one he had jerked off the floor near the blood-soaked corpse of Horatio—sailed and struck The Voice in his nose. Reno caught only a glimpse of the revolving pistol The Voice held, because as soon as the flintlock crashed against the bandit’s face, blood was spurting, The Voice was cursing, and then he was disappearing, crashing against the floor on the other side of the counter. Reno came up, hurdled the counter, and caught an axe handle on his ankles.

This time, Reno cursed, hit the floor hard, and rolled over, but not fast enough, for The Voice jumped on top of him and locked both hands around Jed Reno’s throat.

Now that he had a close look at the gent, The Voice had more than just a rich baritone.

He had the look of a man-killer. Scars pockmarked his bronzed face, clean-shaven except for long Dundreary whiskers, and his eyes were a pale, lifeless blue. Those eyes bulged, and the man ground his tobacco-stained teeth. The nose had been busted two or three times, including just seconds ago by Horatio’s empty .54-caliber pistol. Blood poured from both nostrils and the gash on the nose’s bridge. One of The Voice’s earlobes was missing—as if it had been bitten off in a fight. He seemed a wiry man, all sinew, no fat, and his hands were rock-hard, the fingers like iron, clasping, pushing down against his throat, and cutting off any air.

He wore short moccasins, high-waisted britches of blue canvas with pewter buttons for suspenders that he did not don; a red-checked flannel shirt that was mostly covered by the double-breasted sailor’s jacket with two rows of brass buttons on the front and three on the cuffs. The black top hat The Voice had worn had fallen off at some point during the scuffle.

But he was a little man, no taller than five-two, and a stiff wind—which was predictably normal in this country—would likely blow him over.

Jed Reno figured he was forty years older than The Voice, but he had more than a foot on the murdering cuss, and probably seventy pounds. Jed kept rolling over, and The Voice rolled with him. They rolled like the pickle barrel Sam had knocked over with his right arm as he fell to the floor in a heap and ruined the store’s roof. Rolled against an overturned keg of nails and knocked over the brooms until they hit the spare wagon wheels leaning against the wall.

The Voice came up, pushing off one wagon wheel, then flinging another at Reno, who blocked it with his forearm, and sat up, slid over, and leaped to his feet.

Staggering back toward the sacks of flour, beans, and coffee, The Voice wiped his mouth. The lower lip had been split. Reno tasted blood on his lips, but he didn’t know if it belonged to him, The Voice, or the late Horatio.

“You one-eyed bastard.” The Voice had lost much of its musical tone. More of a wheeze. But the little man was game.

He jerked a bowie knife that must have been sheathed behind his back. The blade slashed out, but Reno leaped back. Again. The Voice was driving him, until Reno found himself against another counter.

The Voice’s lips stretched into a gruesome, bloody smile.

The knife’s massive, razor-sharp blade ripped through the flannel shirt; and had Reno not sucked in his stomach, he would be bleeding more than The Voice about this time. The blade began slashing back, but Reno had found the chains—those he sold to emigrants for their wagon boxes—and slashed one like a blacksnake whip. Somehow, it caught The Voice’s arm between wrist and elbow, and The Voice wailed as the bones in the arm snapped, and the big knife thudded on the floor.

As The Voice staggered back, Reno felt the chain slip from his hand. He was tuckered out, too, and, well, it had been several moons since he had engaged in a tussle like this one.

The chain rattled as it fell to the floor, and The Voice turned and ran for the door.

Sucking in air, Reno charged, lowered his head and shoulder, and slammed into the thin man’s side. They went through the open doorway, over what passed as a porch, and smashed through the pole where the bandits had tied their horses. Those geldings whinnied, reared, whined, and pounded at the two men’s bodies. One, a black gelding, pulled loose the rest of the smashed piece of pine and galloped toward the creek. One fell in the dirt, rolled over, came up—and ran north, leaving its reins in the dirt and wrapped around the broken pole. The other backed up, reared, fell over, and came up. Reno couldn’t tell which way he ran.

He was on his knees, spitting out dirt and blood, while wiping his eyes. He tried to stand, to find The Voice, when he tasted dirt and leather and sinew and felt his head snap back. Down he went, realizing that The Voice had kicked him. He landed, rolled, was trying to come up, when The Voice turned his body into a missile. His head caught Reno right in the stomach. Breath left his lungs. He caught a glimpse of the cabin he called a store flash past him as he was driven into the column that held up the covering over the porch.

The railing snapped. The covering collapsed, spilling more earth, debris, two rats, and a bird’s nest. The two men kept moving. Past the cabin. Over dried horse apples. A fist caught Reno in the jaw. Then another. The Voice packed a wallop. Reno brought up his arms in a defensive maneuver, leaving his midsection open. A fist—it had to be The Voice’s left, for his right arm was busted—hit twice. Three times. Reno fell against the woodpile, rolled over, hit the chopping block, and wondered if he had just busted a couple of ribs.

“Son of a bitch!” The Voice roared.

Reno blinked away sweat, blood, dirt, and dust. He saw the bandit standing next to the pile of firewood. He had a sizable chunk of wood in his left hand and, stepping forward, raised the club over his head.

Reno found the axe buried in the chopping block. Jerking it free, he flung it as he dived out of the way of the descending piece of wood.

He lay there, panting, played out, wondering why the devil The Voice didn’t just finish him off. But that instant of defeatism vanished quickly. Reno rolled over, came up, and spit. He looked left, and then right, and saw his cabin, saw the woodpile, and finally his eyes focused on the moccasins and the ends of the blue pants on the dirt.

Neither the feet nor the legs were moving.

Wiping the blood and grime from his face, Reno limped to the pile. He had to lean against the wood for support, and breathing heavily, he looked down at The Voice, and the axe, and the blood.

“You . . . horse’s . . . arse . . .” Jed Reno wheezed, and made a painful gesture at what remained of his trading post. “All three . . . of you . . . curs . . . dead . . . burnin’in . . . Hell.... Means . . . I gotta . . . clean this . . . mess . . . up . . . myself.”

Jed Reno salvaged what he could from the three dead men. The guns he could resell, even the two flintlock pistols, a matched set of A. Waters pistols with walnut grips—antiquated as they were. Reno also found a nice key-wind watch, and wondered who the dead man stole that from, but decided that the odds highly unfavored the victim—if the victim hadn’t been murdered—coming into Reno’s store and seeing his watch for sale. The boots and shoes might bring a bit of a profit, or he could trade them to the Shoshone woman for some more beads, along with the hats. Not much use with the clothes, especially now that they were all pretty much hardened and stained with dried blood. Reno was lucky. He even found a few gold coins and some silver in the outlaws’ pockets. He was alive, and figured he had made a pretty good trade with the three dead men.

It was shaping up to be one passable, profitable day. But Reno certainly didn’t look forward to cleaning up the mess.

He loaded the corpses onto his pack mule, saddled his bay gelding, and led his cargo away from the post, crossing the tracks of the iron horse. He looked east at the town, still mostly tents, although a few sod houses and frame buildings had been put up. Then he looked west, following the iron rails and wooden crossties laid by the Irishmen working for the Union Pacific Railway. He could see black smoke puffing out of the stacks of a locomotive down the line. Back east, he heard the screeching and ugly hissing and saw more black smoke as another train made its way through the settlement, hauling more spikes, rails, crossties, fishplates, sledgehammers, and maybe even a few more workers.

It was a big undertaking, the transcontinental railroad, and as much as Jed Reno despised the damned thing, he had to admit it was progress. And had made him fairly wealthy.

He rode about five miles north, decided that was good enough, and dumped the bodies into an arroyo. Buzzards had to eat. So did coyotes. And one thing Jed Reno did not like about that railroad was the fact that since they had started laying track across this part of the territory, most of the game had left the country.

Reno could remember talking with Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, and other trappers. It hadn’t been at one of the rendezvous because, the best Reno recalled things, those gatherings had ended by then. Maybe it had been at Fort Bridger. Talk had reached Bridger’s trading post about a railroad being planned, one that would stretch across the country. Carson had shrugged. Bridger had allowed it was true. Reno had laughed and called it a fool’s folly.

“How you gonna get one of them trains across these Rockies?”

“Don’t underestimate man’s ingenuity,” Bridger had said.

“Where, by thunder,” Carson had said, “did you pick up that ‘in-gen-yoo-ah-tee’ word?”

“And in winter?” Reno had said. “Can’t be done.”

Of course, a few years earlier, Reno would never have thought he would be seeing prairie schooners by the hundreds crossing the Great Plains and then across the mountains, bringing settlers from New York and Pennsylvania and other places foreign to a man like Reno, bound for the Oregon country and later California. Farmers. Merchants. Women and children and even milch cows and dogs. One gent had been hauling sapling fruit trees to start some orchards in the Willamette Valley.

Born in 1796 in what was now Bowling Green, Kentucky, Jed Reno had seen much in his day. His father then apprenticed Reno to a wheelwright up in Louisville, and Reno took that for longer than he had any right to before he stowed away on a steamboat and went down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. New Madrid. Then St. Louis. And then he signed up with William Henry Ashley and set out up the Missouri River and became a fur trapper. That had been the life, maybe the best years Reno would ever live to see, but . . . well . . . nothing lasts forever. Beavers went out of fashion. Silk became favorable for hats. Now fur felt had become popular. By Jupiter, Reno had a hat of fur felt on his head now, too.

So when Reno happened upon some men who said they were surveyors, and when they paid him gold to do their hunting and scouting for them, Reno decided that Jim Bridger was a pretty wise gent after all.

Reno had only one eye, but few things escaped his vision, and he had two good ears. And to live in the wilds of the Rockies and Plains since 1822, you had to see, and you had to hear. Reno listened to the surveyors. And he watched.

Apparently, there were a number of surveys going on. A couple were down south, which made a lot of sense to Reno. Weather would be warmer, less hostile, across Texas and that desert country the United States had claimed after that set-to with Mexico. Another up north, somewhere between the forty-seventh and forty-ninth parallels north—whatever that meant. Reno wasn’t sure England would care too much for that. Seemed to Reno that ownership of all that country up north was being debated between the king—or was it a queen now?—and whoever was president of these United States.

But the surveyors kept talking about a war brewing between the states. It had something to do with freeing the slaves or, to hear one of the men who spoke with a Mississippi drawl, it had to do with “a bunch of damn Yankees pushing us good Southern folk around.” That got Reno to figuring that there was no way the United States would put up a railroad across country that might not be part of the United States in a few years. So he paid even closer attention to the surveyors.

Around 1853, some surveyors had been hauling their boxes and making their maps along what most folks called the Buffalo Trail, led by some captain named Gunnison. Something the surveyors called the Thirty-fifth Parallel Route. Reno figured that one died when Ute Indians killed some of the soldier boys, but he also met another one of those young whippersnappers who called himself an engineer. Went by the name of Lander, Frederick W. Lander, who worked for some outfit called the Eastern Railroad of Massachusetts. Lander told Reno that there could never be a railroad in the South, but a railroad had to connect the Pacific with the Atlantic because if war came—not among the states, but against a European power with a strong navy and mighty army—the United States would not be able to defend California without “an adequate mode of transit,” whatever that meant.

So Reno decided to throw up a trading post along Clear Creek in the Unorganized Territory, take a gamble that Lander was right, and that eventually he’d be selling items to greenhorns stopping for a rest on this transcontinental railroad.

The post was a combination of logs—which he had hauled down from the Medicine Bow country—and dirt. He had built it into a knoll that rose near the creek, digging out a cave that he knew would be cool enough in the summer and hot enough in the winter. The logs stuck out and made the post look more like a cabin, though, and gave it more of an inviting feel. Reno had never cared much for those strictly sod huts that looked, to him, like graves. This way, part log cabin, the post didn’t seem completely like a grave to Jed Reno.

A few years later, Lander came back again, and this time he had some painter guy with him. That’s when Jed Reno began feeling pretty confident about his investment. After all, if you hired some artist to paint some pretty pictures of you working, then you had to think that this was being documented for history.

Besides, even if it didn’t happen, if the railroad went north or south or never at all, well, Jed Reno still had a place he could call home, that would keep him warm in the winter and cool in the summer. He had a good source of water, and could fish or hunt or get drunk or just sit on his porch—if you could call it a porch—and watch the sun rise, the sun set, the moon rise, the moon set. By Jupiter, he was pretty much retired anyhow, like ol’ Bridger.

Of course, the war came—just like everyone had been talking about—and the surveyors and engineers stopped coming. Poor young Frederick Lander. He joined up to fight to preserve the Union, and from the stories Reno heard, the boy took sick with congestion of the brain and died somewhere in Virginia in 1862. Wasn’t even shot or stuck with one of those long knives or blown apart by a cannonball. Reno wondered if that gent with the paintbrushes—some gent named Albert Bierstadt, who had dark hair, a pointed beard, and penetrating eyes—ever amounted to much.

Most of the blood inside the trading post had been covered with more dirt, which Reno packed down with his moccasins. The merchandise that had been busted, or soaked or stained with blood, he tossed into a canvas bag and hauled to the smelly dump that the settlers, who had not moved on with the railroad, had started up and was already attracting vultures and rats and coyotes and flies. But it was far enough away from Reno’s post that the smell seldom bothered him too much.

He salvaged most of the merchandise, not that it really mattered. Since the railroad had moved on, Reno had not seen much business, and since the trains brought only supplies and more workers, it wasn’t like settlers were stopping to spend money on trinkets and blankets and tin cups. Reno began to doubt if he could ever sell anything else—not that he really cared one way or the other.

Fixing the hitching rail was probably the easiest thing, since he had hammers and plenty of nails and even some spare ridgepoles, located behind the post, he could use. The roof and the porch, however, were another matter. He had to use another pole. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

The Edge of Violence

William W. Johnstone

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved