- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

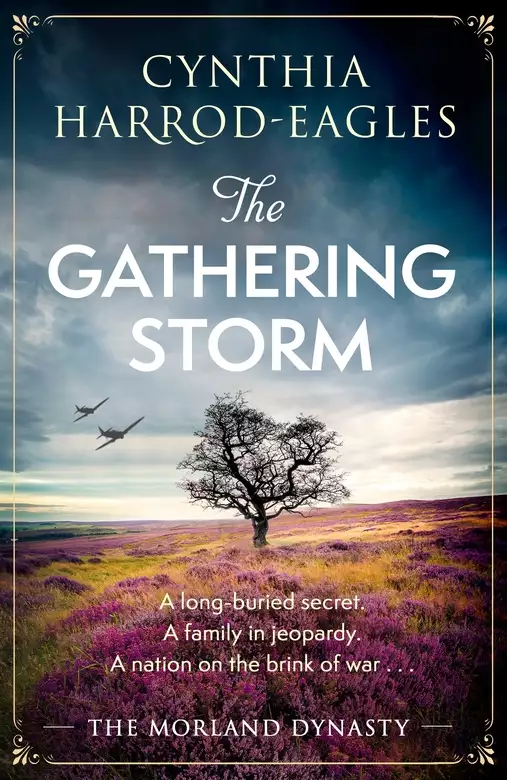

Synopsis

The eagerly-awaited return to the acclaimed Morland Dynasty series, and the 100th novel by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

England, 1936

The reign of Edward VIII has begun, but danger for the monarchy already looms on the horizon. At home in Morland Place, Polly Morland feels alone and abandoned, with her brother summoned to France by his old employer. James soon finds himself travelling to Russia, whereas Polly will voyage on the Queen Mary with New York - and a long-lost love - her destination. Soon the family are scattered to the four winds, from Hollywood to war-torn Spain.

Working for the Air Ministry on new fighter planes, Jack fears that his children are not taking the increasingly tense situation in Europe seriously enough. The nation is divided over which is the greater thread: Communist Russia, or Fascist Germany. As the storms of war gather, they will threaten to overwhelm the Morlands and destroy all that they have worked for...

The BRAND-NEW novel in the acclaimed Morland Dynasty historical fiction series with over a quarter of a million copies sold. The perfect read for fans of Downton Abbey, Lucinda Riley and The Crown.

Release date: December 3, 2024

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 82500

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Gathering Storm

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

When Polly came in after breakfast she said, ‘I wondered where they’d all gone. You wanted to see me?’

Burton was silent a moment, thinking how fine she looked. For some women, their mid thirties are a time when the dewy but unfinished beauty of extreme youth blends with the serenity and confidence of maturity. Polly had always been a belle in the classical, blue-eyed-golden-haired mould: now she was a lovely woman, with a fine, upright figure in well-cut riding clothes, her golden hair drawn into a tight, practical bun.

She gave him a quizzical look. ‘What is it? Have I got a smut on my nose?’

He shook himself. ‘No, indeed.’ He hurried on: ‘I have something to tell you – well, two things. One personal, one business.’

‘Personal first, then.’ She perched on the edge of the desk.

‘I don’t know, really, whether it’s something you need to know, or even want to know, but I would feel odd not telling you. Joan – my wife – we are expecting a child.’

‘That’s wonderful. Congratulations.’ Polly’s reply was automatic, the product of her careful upbringing, as was her smile. And of course it was good news!

But when John Burton had first come into her life as her estate manager, she had been feeling very lonely – a young widow, recently returned from America, her adored father having also died. Of course, she had been surrounded by relatives – she still was – but where was the special person to whom she mattered most in the world, who was interested in every facet of her life? She had longed for that perfect intimacy; had wanted, in a word, a lover.

She had immediately liked and trusted John Burton, and as they had worked closely together, learning the complexities of running the estate, it was natural that a warmth had grown up between them. It had been foolish of her to allow it to develop into a tendresse. She had never so much as heard him mention Joan Formby’s name until the day he had introduced her as his fiancée. Polly and Burton had spent so much time together, she had forgotten he might have a life outside Morland Place.

She was now ashamed of what her feelings had been. He was her agent, a nice, warm-hearted, straightforward man and an excellent employee: he would be mortified if he ever found out she had harboured a silly fancy for him. ‘I’m delighted for you,’ she went on. ‘When is the great day?’

‘Oh, not until September,’ he said, pushing back the lock of barley-fair hair that liked to escape and fall over his forehead. ‘It’s early days – we haven’t even told Joan’s parents yet.’

‘You’ll need a larger house,’ Polly said briskly. ‘Your cottage is really only suitable for a bachelor. Mrs Burton has been very patient to live there for eighteen months without complaint.’

‘Sixteen months,’ he corrected. ‘As a matter of fact—’

‘You already have somewhere in mind,’ she capped him.

‘As your agent, I naturally know all the properties on your estate.’

‘And which has taken your fancy?’

‘Kebble’s Cottage, on Moor Lane.’

‘Oh, yes. Isn’t it the one with the roses all over the front?’

‘That’s it. There’s a good bit of garden at the back, too. The previous tenant worked it well, so we’d be able to grow vegetables. Even perhaps keep a couple of hens.’

Polly had had enough of imagining their domestic bliss. ‘Well, you have my blessing to take it, and I wish you very happy there. Now, what was the business matter you wanted to raise?’

He reached for a piece of paper in front of him. ‘I’ve a letter here from York council. To summarise, they are continuing with the slum clearances in the Hungate area, and they want to build council houses outside the walls for the people they displace. You know they did the same sort of thing when they cleared Walmgate and bought the land at Tang Hall?’

‘What has that to do with me?’ she asked. She had a feeling she would not like where this was going.

‘They want to buy twenty acres of Morland land up at North Field, along the Knaresborough road.’

‘For housing? But that’s good farmland,’ she objected.

‘Indeed, but when you move people, you can’t take them too far from their jobs. And they need access to public transport, so you have to site the estate along a road – which makes it easier to lay in services, too: water and sewerage and so on.’

‘My father took years to build up the estate. I’m not going to reduce it,’ she said.

Burton gave her a troubled look. ‘You may not have a choice, ma’am. Under the Housing Act of 1885, local authorities have the power to purchase land compulsorily.’

Polly’s brows drew down. ‘You mean, they could make me sell?’

‘I’m afraid so. It’s the law.’

‘But the land belongs to me! If they can just take it, we might as well be living in Russia!’

‘The thing is—’

Polly turned away abruptly. ‘I can’t talk about it now. I’m on my way out.’

‘We’ll need to reply to them fairly soon, or—’

‘I’ll think about it,’ she snapped, and left him.

It was a dry day, but perishingly cold, and not a single dog volunteered to accompany her as she went out into the yard. On the shaded side the frost lay like snow along the foot of the wall; it glistened on the cobbles. One of the grooms, Hodgson, led Zephyr out and helped her mount. She didn’t blame him for scurrying back to the tack-room as soon as she had the reins.

Zephyr clattered over the drawbridge and out onto the track, and Polly had a sense of being completely alone in the world. There was no-one about; nothing stirred, not even a bird. The gauntness of February was unsoftened yet by any new growth; even the blackthorn slept. The trees stood stark and bare against a uniform grey sky, and the air was grippingly cold, the sort of creeping chill that worked its way inside your clothes, and numbed your hands.

Zephyr was inclined to be nappy at first, wanting to get back to his stall, but she drove him into a fast canter to warm them both up. They went out as far as Rufforth Grange before she turned back and made a circle towards Twelvetrees, her cousin Jessie’s place. She felt the need of advice.

Jessie was in one of the paddocks, lungeing a young horse, with her daughter Ottilie in the saddle. Ottilie, slight with curly fair hair, the image of her mother, was small for thirteen, and Jessie often used her when backing a horse for the first time. The appearance of Zephyr on the other side of the fence distracted the horse and it whinnied and tried to nap towards the gate. Jessie looked round, then waved to Polly and called the horse in to the centre.

‘I need to talk to you,’ Polly said. ‘It’s important.’

‘Go on, I’ll join you in a minute,’ Jessie called back. ‘I’ve just about finished.’ She turned to her daughter. ‘Sit quite still and don’t use your legs. I want him to listen to me, not you.’ She sent the horse back out to circle on the other rein.

Polly rode on. By the time she had settled Zephyr in a spare stall, Jessie and Ottilie had arrived, walking the young horse between them. Polly heard Ottilie say, ‘I’ll take him, Mum. You go and talk to Polly.’

Jessie’s head appeared over the half-door. ‘Come up to the house and have a cup of tea,’ she said. Her eyes were watering with the cold and the tip of her nose was red. ‘I’m frozen to the marrow. I think we might be in for some snow.’

Polly gave Zephyr a last pat and joined her. ‘Oh, I pray not. That’s all I need to make a perfect day.’

‘Why? What’s happened?’ Jessie asked. They walked up the path to the house, their footsteps crackling on the skim of ice between the stones. Twelvetrees was a solid, square, stone house, designed to keep out the weather. Jessie and Bertie had had it built to their own plan, with modern amenities, and it was deliciously warm inside.

‘This must be the only truly warm house in England!’ Polly exclaimed.

‘I suppose you were used to central heating in New York,’ Jessie said, easing off her gloves. ‘I must say, it’s a treat on a day like this. It’s making me soft, though. I was much hardier when I lived at Morland Place.’ She had grown up there. She had inherited Twelvetrees from her father, and she and her husband bred and schooled horses for sale.

‘Icy draughts and cavernous spaces,’ Polly agreed. ‘A little pool of heat around each fire, and Arctic wastes in between. One of these days I’m going to have central heating put in – when I can work out where to put the boiler. That’s the trouble with an ancient pile – especially a moated one!’

Jessie smiled indulgently. ‘But you wouldn’t exchange Morland Place for any other house on earth.’

‘Well, no, but that’s nothing to do with it. You should see my chilblains.’

‘So, tell me what’s ruffled your feathers,’ Jessie invited, as they stripped off coats and gloves.

‘John Burton’s been lobbing bombshells at me. First he tells me his wife’s expecting a baby—’

‘Why is that a bombshell?’

Polly caught herself up. ‘Oh, you know how demanding a first baby can be. He’ll have his mind on anything but his work for the next year at least.’

‘I’m sure he won’t let it affect him. He’s tremendously diligent.’

Polly hurried on. ‘And then he tells me that the York city authorities want to buy some of my land for council houses. And tells me that they can force me to sell. It’s outrageous!’

Jessie said, ‘This calls for Bertie’s wisdom. I think he’s in his study. Shall we go and see?’

Sir Percival Parke, who was a cousin to both Jessie and Polly, had always hated his given name and had never been known as anything but Bertie. He had served with distinction in the war, one of the few to fight all the way from 1914 to 1918, winning the DSO and the VC, ending as a brigadier and working afterwards in the War Office. Now he was happy to spend his days quietly at home, farming his estate and enjoying the company of his adored wife and three children.

He was very fond of Polly, and admired the way she had thrown herself into running the Morland Estate. She had bought it from her brother James when death duties had threatened its dissolution. Her late husband, Ren, had left her a large fortune, and James, though a countryman to his fingertips, had no head for business. Polly’s head, Bertie reckoned, was as hard as any man’s: she had run her own fashion house in New York before her marriage, and that was no mean task.

He was studying milk records when his wife ushered Polly in, saying, ‘Can we disturb you, dearest?’

‘I can’t think of anything nicer. What’s happening?’

‘Polly needs advice,’ said Jessie.

As well as the radiator there was a fire in his room, for cheerfulness. Bertie moved chairs and got them all settled around it before inviting Polly to ‘tell’.

Polly told. ‘I thought an Englishman’s home was his castle,’ she concluded. ‘Magna Carta and all that sort of thing. Is John right? And who dreamed up such a terrible law?’

‘Well, I suppose you could say it was an extension, in a way, of the old Enclosure Acts,’ Bertie began.

‘She doesn’t want a history lesson, darling,’ Jessie intervened.

‘Oh, it was a rhetorical question, was it?’ Bertie said, with an indulgent smile.

‘They can’t really force me, can they?’ Polly asked hopefully.

‘I’m afraid they can. And before you howl again, think about things like the railways, and new roads. And airfields during the war. On a tiny island like this they could never get them built if landowners could refuse to sell.’ Polly was still looking mulish. ‘You wouldn’t want to be without the railway, now, would you? Quite a bit of Morland land had to be given up for that, if I remember rightly.’

‘But this isn’t for a railway,’ Polly said.

‘Compulsory purchase is allowed for projects that are considered to be in the public interest.’

‘Why do you object so much?’ Jessie asked.

‘Because Papa spent his life building up the estate. He worked and slaved to buy back all the land Uncle George sold, so that he could pass the estate on intact. He’d have a fit at the thought of selling it again. I would never part with any of my land – it would be a betrayal of everything Papa stood for.’

‘I wonder,’ Bertie said. ‘After Morland Place and his family, the one thing Uncle Teddy really loved was York.’

‘And the railways,’ Jessie added.

‘He loved the railways because they brought prosperity to York,’ Bertie said. ‘He supported anything that benefited the city. Don’t you remember how he started the York Commercials during the war?’

Jessie smiled. ‘Oh, yes – because Leeds had its Pals unit, so York had to have one too.’

Polly looked from one to the other. ‘So you’re saying he’d approve of the slum clearances?’

‘He helped with some of the early ones,’ Bertie said.

‘And you think he’d like there to be a council estate on Morland land?’

‘I don’t think he would fight against it,’ Bertie said. ‘If you clear a slum, the people have to go somewhere. Another thing to consider,’ he went on, seeing that she still wanted to argue, ‘is that if you sell at the first approach, rather than waiting to be forced, you may have some say over exactly where the building will be sited. That’s worth having.’

Polly sighed. ‘I suppose one has accept change,’ she said reluctantly.

‘I’m afraid there may be more on the way,’ Bertie said. ‘I had a chat with Jack on the phone last night.’ Jack was Jessie’s brother, who had been a flier in the war and was now working in aircraft design. ‘He said that Hugh Dowding told him there’s going to be a big reorganisation in the RAF. It will mean a lot of new airfields being built.’

‘Now, darling, don’t start Polly worrying about that,’ Jessie said. ‘To change the subject, tell me, what are James’s plans? Does he have any? I thought he was only coming home for Christmas, but here we are in February and he’s still at Morland Place.’

‘He’s waiting to hear from Mr Bedaux. He and his wife went to America for Christmas and didn’t need James with them.’

Charles Bedaux was an American production engineer whom James had met when invited to join his expedition across British Columbia in 1934, and had since worked for in various capacities.

‘But I think James is worried he’s plunged into some new scheme and forgotten all about him. I don’t mind for my own part – I like having him around. I was quite dreading him going. But, of course, now Lennie’s coming for a visit, so I’ve got that to look forward to.’

‘Oh, yes,’ Jessie said. ‘It’ll be lovely to see the dear boy again. We must have a dinner for him.’

‘When is he expected?’ Bertie asked.

‘Towards the end of March,’ Polly said. ‘I hope he stays a long time. It was lovely when I lived in New York and we saw each other all the time.’

‘Perhaps he’ll stay for good,’ Jessie suggested. ‘After all, he’s got nothing to go back for, really, has he?’

‘Except his business empire,’ Bertie said drily.

Polly thought about her cousin Lennie – after her father, the person who had always been the most devoted to her. She imagined him at Morland Place, imagined them riding together, walking together, talking. They had so many memories in common. ‘We’ll have to find something for him to ride while he’s here,’ she said happily, and the conversation turned, as it so often did quite naturally, to horses.

In Whitley Heights, above Los Angeles, the morning air was cool and scented with pine, and the sun threw long shadows across the terrace from the orange trees that shaded one end. Lennie, dressed as far as trousers and shirt, looked out over the hills, where the early light lay like silver gilt across the dark trees. The only sound was of birdsong.

On the first terrace below, the gardener was raking a few leaves together on the rectangle of lawn; on the second terrace, the turquoise pool rippled gently, reflecting the sky. Everyone on Whitley Heights had a pool, but lawns were not natural to California. It was that emerald oblong, maintained at such expense, that marked Lennie out as a rich man. He shook his head at the idea. He had made his first million dollars so long ago he never thought of himself as rich. Yes, it was agreeable to have the money to invest in his interests and to see them flourish. It hardly mattered that, flourishing, they then made him even more money.

For the last nine months nothing much had mattered to him. His pregnant wife had been killed in a car smash back in June, and his life had been dark. Only recently had he felt his internal landscape shifting, and this morning he was aware that something heavy inside him had settled into a new position. The day was something to be looked forward to, rather than merely endured. And in this sweet early morning, the planning of the trip he was intending to take was no chore but part of the pleasure. He had a few more things to settle, to ensure that his business would carry on without him, and some last-minute presents to buy. Then there would be just his packing to do.

Wilma, his housekeeper, would want to do the packing herself, and would argue strenuously about it, but holding his own against her would be another sign that he was getting back to normal. She had taken a loving stranglehold on his life these last eight months. She had been with him for ten years, ever since he first came to California, and together with Beanie, his driver, formed the nucleus of a tight, loyal household. The way they schemed to protect him, he sometimes thought they believed him to be a lovable imbecile.

He heard Wilma come out of the house behind him: the slip-slap of the dreadful broken-down slippers she insisted on wearing was unmistakable.

‘Breffus about ready, Mr Lennie. You want it out here?’

He turned to smile at her. ‘Might as well,’ he said. She would have squeezed him juice from his own oranges; and her coffee was the best on the west coast. Perhaps she would have made him pancakes.

She didn’t smile back. Her lower lip, reliable gauge of her mood, was sticking out. ‘Might as well get all o’ God’s good sunshine you can, ’fore you go to England. How folks can live in all that fog beats me.’

‘The sun shines in England too, you know,’ he said.

‘Nu-huh,’ she countered. ‘I seen it on the movies. Everybody creeping about in the fog. Enough to make you crazy. They say English folk are all mad. You should stay here, Mr Lennie, an’ let me take proper care of you.’

‘It’s not for ever. It’ll only be for a few weeks,’ Lennie said – though he wondered. He had a feeling of standing at a crossroads. His life here in California seemed to have paused, as though a phase was completed. And in England there was Polly, whom he had loved all his life, though without return: she had only cared for him as a cousin. But Ren, her husband, was dead, killed in an aeroplane crash shortly before she had given birth to their son, Alec. Now Lennie’s Beth was gone too, and enough time had passed for both of them to start thinking about a new future. Perhaps together? She had always depended and leaned on him. She had given her son the second name of Lennox, in his honour. Surely there was something there to work with. Who knew? Perhaps the time was right for them.

‘What am I s’pose to do while you’re away gallivanting?’ Wilma was grumbling. ‘Sit on the porch and rock?’

‘Oh, you’ll find something. Clean the whole house from top to bottom, if I know you. What’s for breakfast?’ he prompted.

‘I’m fixing you pancakes,’ she said

It was odd how often she read his mind. Or was it vice-versa? ‘With bacon?’

‘Don’t I always fix bacon with pancakes? What kind o’ question is that?’ She was reluctant to let go of her sense of grievance, and he heard her muttering her way to the kitchen: No good reason I know of for folks to go skedaddling off to England every five minutes …

She was back too soon, and empty-handed. ‘You got a visitor. Mr Rosecrantz. I told him it’s too early, but he says it’s important.’

‘Bring him out here,’ Lennie said. If he had to forgo his breakfast, at least he could still have the fresh air. ‘And bring coffee, will you?’

He guessed it must be something serious if he had come in person instead of telephoning. Michael Rosecrantz was the agent of Lennie’s cousin and sometime protégée, Rose Morland, the young movie actress. As a large shareholder in ABO Studios, Lennie had been in a position to promote and oversee her early career, but as her success grew, he’d advised her to get a proper agent. At that point he had taken a step back; but Rosecrantz notwithstanding, he had been unable to stop feeling responsible for her.

Then a year ago, in March 1935, she had got married, with a great deal of celebrity ballyhoo, to her co-star in The Falcon and the Rose, Dean Cornwell. Since then, Lennie had rather taken his eye off her. Between a husband and an agent, to say nothing of a dresser, a secretary, a publicist and a tame lawyer, Rose had plenty of people to take care of her, and he’d felt it was time to let go. Then Beth had died, and he had turned in on himself, with no interest in the outside world. He had not so much as glanced at a Motion Picture or Modern Screen magazine in months, so he had no idea what Rose had been up to lately.

Rosecrantz, tall and angular, lean-faced with thick dark hair and a fashionable sun-bronze, came striding out onto the terrace, passing Wilma in the doorway, to take Lennie’s hand in a firm, professional grip. He scanned Lennie’s face with quick, keen eyes. ‘You know why I’m here?’

‘Haven’t a clue,’ Lennie said. ‘I’m guessing it’s something to do with Rose.’

‘You haven’t heard, then? I thought at least Estelle might have called you.’

‘I haven’t spoken to Estelle in a year,’ Lennie said. Estelle Cable was Rose’s publicist. ‘What’s all this about?’

‘Rose was arrested yesterday for public intoxication, coming out of the Parrot Club on Wilshire Boulevard.’

‘Arrested?’ In California, being drunk in public was at worst a misdemeanour, and the police only intervened in extreme cases, when a nuisance was being caused.

‘It wasn’t just cocktails,’ Rosecrantz said impatiently, ‘There was cocaine, and who knows what else? She and her companions had been kicking up a row and making themselves unpopular, and when they finally got thrown out, she collapsed unconscious on the sidewalk. Her “good friends” abandoned her as soon as they sniffed trouble, and since the doorman couldn’t rouse her, the manager, who’d already called the cops, rang for an ambulance. She was taken to Wilshire Park Hospital and had her stomach pumped.’

‘Oh, my God!’

‘Some journalist outside the club called Estelle, and she rushed over and got Rose transferred to the Ardmore.’

The Ardmore was an expensive private clinic. ‘Is she all right?’

‘She will be – sick and sore, and probably depressed, but that’s no more than she deserves. It’s the hell of a mess, Len. After Falcon, and then the wedding, she’s big news. This kind of bad behaviour … And the stomach pumping in particular … Someone at the hospital will talk. We’ll never keep it quiet this time.’

‘This time? Has she pulled stuff like this before?’

Rosecrantz took a breath. ‘I forget how out of touch you’ve been. Estelle’s managed to keep her out of the papers, but there’s been plenty of gossip. I guess it hasn’t got as far as you.’

Lennie was perplexed. ‘I thought she’d be happy after she married Dean.’

‘That marriage has been a disaster,’ Rosecrantz said impatiently. ‘I was against it from the beginning, but no-one listened to me. Cornwell’s bad news. That clean-cut, boy-next-door image is barely skin deep – he’s a troubled creature. And Rose has followed his lead. Wild parties, drugs – she’s out of control.’

Lennie raked his hair. ‘Why did no-one tell me?’

Rosecrantz shrugged. ‘I’m only coming to you now because I don’t know what else to do. Maybe you’ve still got some influence with her. Because I tell you now, Len, this could be the end of her. You know how particular the studios are about their stars toeing the line. ABO’s going to kick up. Al Feinstein could cut her loose.’

‘But you could talk to Al—’

‘I’m cutting her loose,’ Rosecrantz said harshly. ‘I’m sorry, I really am, because I like the kid—’

‘She’s made you a heap of money,’ Lennie said sourly.

Rosecrantz didn’t flinch. ‘I made her money, she made me money. That’s the deal. But I’ve got other clients. I’ve got their reputations to think of. And my own. I can’t afford to be associated with this. I’ll tell Rose in person when she’s fit to be spoken to. But I’m also telling you, because I know you’re the nearest thing she has to a father. If you care about her, you need to reel her in. Talk to her like a Dutch uncle before it’s too late.’

He rose up to go. Wilma stood in the doorway with a tray of coffee. He said, ‘Thanks, but I can’t stay. There’s a lot of fire-fighting to do. I’ll see myself out,’ he added, as he passed Wilma.

In the ensuing silence, Wilma fixed Lennie with a reproachful gaze, her lip now resembling a sugar-scoop. Lennie examined her face. ‘Did you know about this?’

She didn’t pretend not to have been eavesdropping. ‘About Miss Rose cutting up frisky? Sure I did. That Beanie, he hears everything. He told me what she’s been at, weeks and weeks past.’

‘Why didn’t you tell me?’

‘Not my place,’ she said stubbornly. Then, ‘You been grieving, Mr Lennie. And far as I knew, you’d dropped her even before that.’

‘I didn’t drop her, I just – took a step back. My God, if she had her stomach pumped, she must have been bad! She could have died! You can’t believe I wouldn’t want to know.’ Her eyes slid away from his. ‘What did Beanie tell you?’

Beanie, his driver, always knew all the Hollywood gossip. There was a network of drivers who exchanged information while they waited outside studios and restaurants and clubs. And everyone who was anyone in Hollywood had a driver.

‘Best you talk to Miss Rose about it,’ Wilma said. ‘Maybe some of it’s not true. Alcohol and drugs and all sorts o’ wildness. Other men—’

‘What? She’s only been married a few months!’

‘That Mr Cornwell, he’s no angel. He’s led her wrong, you can bet on that. I’ll get your breffus now.’

‘No, skip it, there’s no time. I must get over to the clinic right away. Tell Beanie to have the car ready in ten minutes.’ Other men? Lennie thought, with a sense of doom. It was supposed to have been a love-match. And while the studios liked their stars to have romances, and loved them to get married, they didn’t sanction promiscuity. He hastened indoors to finish dressing.

Between 1929, when Talkies became widespread, and 1934, there was a period of freedom in the making of movies. On-screen violence, profanity, crime, drug use, prostitution, promiscuity … nothing was off limits. It was as if, ordinary decent folk complained, bad behaviour was being actively promoted, and they feared it would corrupt society.

In the first half of 1934 a campaign gathered way to persuade the government to take over the censorship of films. The possibility of government interference was enough to frighten the studios into adopting self-censorship as the lesser evil. Under the leadership of Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, a Production Code was drawn up. Every motion picture released on or after the 1st of July 1934 had to acquire a certificate of approval from the MPPDA.

The Hays Code, as it was generally known, covered everything. Profanity – the use of words like God, Jesus, hell, damn, bastard and so on – was forbidden. There was to be no nudity, even in silhouette; men and women were not to be shown in bed together; no excessive or lustful kissing, especially if one of the characters was a bad person. Crime was not to be treated sympathetically in case it encouraged the impressionable. There was to be no mockery of the clergy or law-enforcement officers or the institution of marriage. Scenes depicting childbirth, surgical operations, or the judicial death sentence were outlawed. And the Flag was to be treated at all times with respect and dignity.

It was natural that, with the content of films so strictly overseen, the studios should clamp down on their stars. In the early days actors, even the females, had enjoyed a freewheeling, buccaneering kind of life. But now even a big star like MGM’s Mr Clark Gable had to conduct himself carefully in public: he was separated from his wife, Ria Langham, but she was unwilling to grant him a divorce, so if he romanced any lady it had to be strictly outside the bedroom. Divorce was acceptable in Hollywood, but adultery was anathema.

Lennie pondered these things as he was driven over to the nursing home in Wilshire. Bea

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...