- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In 1918 the Great War has taken so much from so many, and it threatens to take even more still from the Hunters, their friends and their servants.

Edward, in a bid to run away from problems at home, decides not to resist conscription and ends up at the Front. Sadie's hopes for love are unrequited, and Laura has to flee Artemis House when it is shelled, and she finds herself in London driving an ambulance. Ethel, the nursery maid, masks her own pain by caring for other people's children, but she must take care not to get too attached.

The government has to bring in rationing, and manpower shortages means the conscription age is extended. The Russians have fallen out of the war, and a series of terrifying all-out attacks drive the Allies back almost to the Channel, and for the first time England faces the real prospect of defeat. No one can see an end to the war, and yet a small glimmer of hope remains....

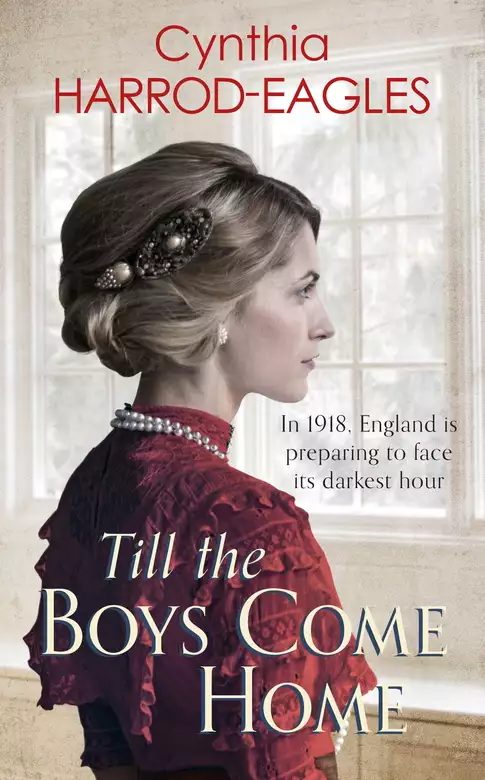

When the Boys Come Home is the fifth book in the War at Home series by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles, author of the much-loved Morland Dynasty novels. Set against the real events of 1918 at home and on the front, this is a vivid and rich family drama featuring the Hunter family and their servants.

Release date: June 28, 2018

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Till the Boys Come Home

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

Snow was blowing along Downing Street. The sky was so low and grey there was twilight at midday; but inside No. 10 electric light banished the gloom, and in the State Dining Room, a fire was burning brightly in the fireplace under the massive portrait of George II.

Lord Rhondda, the food controller, had murmured something tactless about coal rationing, but Lloyd George shrugged it off with a droll remark about Rhondda’s having made his fortune from coal. Then Bonar Law retold the joke about Rhondda’s having survived the Lusitania sinking – it was said he was so lucky he bobbed to the surface with a big fish in either hand. Rhondda took it in good part, leading the laughter at the ribbing.

There was a convivial atmosphere around the table, which Edward Hunter found remarkable, given the dire straits the country was in, in this fifth year of the war. Even more remarkable was his being here at all, in a company that included the Prime Minister, the Chancellor of the Exchequer and Field Marshal Haig, commander-in-chief of the British Expeditionary Force. Edward kept his ears open and his mouth shut, as befitted the lowest and least.

At first nothing serious was spoken of: these men, with the weight of the world on their shoulders, needed to relax. Several amusing anecdotes were exchanged before the war was even mentioned; and then it was only to take light-hearted bets on when it would end.

The Prime Minister put up a hundred cigarettes that it would be finished off in the late summer of 1919, once the Americans had ‘got their feet under the table’.

Lord Derby, the war secretary, raised him a hundred cigars that it would be over by next New Year.

‘But where will you get a hundred cigars, Derby?’ Lord Forbesson of the War Office parried. ‘Don’t tell me you are a hoarder? Rhondda, take note!’

‘I’ve no window to look into a man’s soul,’ said Rhondda.

‘Bonar, back me up,’ Lloyd George appealed. ‘Summer 1919. Late summer.’

‘I’ll not bet on the war,’ Bonar Law rumbled. ‘On a horse, mebbe. What’s going to win the Guineas in April, Derby?’

‘My filly, of course,’ said Derby.

‘Man, that’s what you said last year, but Vincent took it with Diadem!’

‘A fluke,’ Derby said, waving a hand. ‘Vincent was lucky. You may put your hat on Ferry.’

‘Unpropitious name,’ remarked George Barnes. ‘Ferries are damned slow.’

‘Not mine. She’ll win by a length,’ Derby insisted.

‘Never mind horses, what about my bet?’ Lloyd George said. ‘Sir Douglas – what do you say? When’s this war going to end?’

It was a brave question, and the room held its breath. If anyone was aware how bad things really were, it was Haig – and it was well known he’d been at outs with Lloyd George in the past, blaming him for the shortage of manpower and ordnance.

But Edward’s patron, Lord Forbesson, who knew Haig well, dropped Edward a wink. Haig was stiff and dour in his demeanour, but it was from an unexpected but deep shyness: underneath, he was a great optimist. He turned his pale blue eyes on the Prime Minister and said, ‘Oh, I’m with Lord Derby. We’ll be out of it by the New Year.’ An eruption of protest and comment followed. When it died down, he added, ‘One way or another.’

Edward almost shivered. The idea that they might lose the war had never been entertained, however bad things had sometimes seemed. But now they were going to have to fight on without Russia.

Driven to its knees by revolution and misgovernment, starvation and lack of equipment, Russia had signed a cease-fire with Germany and was negotiating for peace at Brest-Litovsk on the Polish border. The Russians had been unreliable allies, but by keeping the Germans occupied on the Eastern Front had taken some pressure off the Allies. Once they were out of the war, Germany could direct its undivided attention to the Western Front.

The mood around the table sobered. Haig said that the next four months would be critical. ‘Germany’s moved seventy-five thousand men back from the Eastern Front,’ he said. ‘More to come.’

‘But surely,’ Lord Derby said, ‘they won’t risk their whole reserve in an all-out attack?’

‘It would be a gambler’s throw,’ said Haig, ‘but we can’t rule it out.’

‘You’re all right for guns and ammunition,’ Lloyd George asserted warily. ‘We’ve doubled output from the factories in the past eighteen months.’

‘Thanks to the women workers,’ Lord Forbesson said. ‘Without them, the Royal Ordnance couldn’t function at all.’

‘Women will always do what’s required of them,’ Haig commented.

Rhondda agreed. ‘They are a great deal tougher than we credit them for. All the same,’ he looked around the table, ‘we have to take war-weariness into account.’

It was a phrase unknown until recently. The Germans may sicken of the war, the French may falter, but the British lion would never be daunted. Yet, having gone into the war in the highest of spirits and determination, the nation was now wondering how much more it could take.

The casualty lists; the sacrifice of life; the bombing raids on British cities: these were afflictions to be borne bravely. But then there were the shortages, the queues, the blackout, the long hours and the sheer unrelenting slog. Fatigue, anxiety and sorrow – they wore down the spirit. For soldiers, there was the camaraderie of a shared endeavour, the force of duty and the immediacy of danger to stiffen them. But the ordinary people had dreary toil, in hardship and deprivation, with little thanks or praise – and no end in sight.

War-weariness: everyone knew about it, but what could be done about it?

‘Well,’ said Lord Derby, ‘we certainly can’t stop now. Germany must be defeated.’

Lord Rhondda turned to Edward. ‘What do you say, Hunter? What can we do to improve morale at home?’

It was something he and Rhondda had been discussing, and he saw now why he had been invited to this luncheon – to present, as an outsider, what would probably be an unpopular idea. In politeness, they would have to hear him out. Whether they would agree was another matter.

‘We should introduce food rationing,’ he said.

There was instant outrage. ‘It’s un-English,’ Milner objected.

‘They won’t take more interference,’ said Barnes. In some ways the worst thing about the war was the ever-increasing regulation of a people who had never had much truck with officialdom

‘I fear it would only increase ill-feeling,’ said Law, cautiously.

‘Just so,’ said Derby. ‘Set people against each other. Accusations of cheating. Snoopers peering into shopping-baskets.’

‘And actually draw attention to the shortages,’ Barnes said.

‘People understand that there are shortages,’ Edward said. ‘They “do without” remarkably patiently. What wears them down is the uncertainty. They queue for hours, not knowing whether, when they get to the head of the queue, there will be anything left to buy.’

Haig said, ‘My men know what’s going on at home. Their wives write to them, and it affects their morale.’

‘But it smacks of socialism to me,’ Montague muttered. ‘Not the business of government to tell people what to eat.’

‘Only the basic necessities need be rationed,’ Edward said. ‘If everyone’s sure of getting the same amount of them, then there’s no competition at the shops, and no bad feeling. It would lift a dark cloud from our ordinary people.’

Lloyd George said, ‘No-one likes the idea of rationing, but it may be a necessary evil. How would it work, Rhondda?’

‘Prices would have to be fixed,’ Rhondda said. ‘And it would have to be backed up by the law, with compulsory tickets or tokens, and fines for infractions.’

‘Who’s going to enforce it?’ said Barnes. ‘The police won’t have time – they’re fully stretched already, with so many gone to the Front.’

‘There would have to be food inspectors,’ said Lord Rhondda.

‘God help us,’ Barnes muttered, rolling his eyes. ‘More busybodies with armbands.’

Edward couldn’t help smiling to himself as the vision of Mrs Fitzgerald, the rector’s wife in his home village, came to mind. There would never be a shortage, he thought, of people willing to take up the post of interfering with their neighbours.

After more discussion, Rhondda said a further benefit of rationing was that the general nourishment of the population could be fixed at pre-war standards, resulting in better health. ‘And that means increased output. Healthy workers produce more guns and shells.’

‘Which brings me, gentlemen,’ said the Prime Minister, ‘to another point. Recruitment. Sir Douglas?’

Haig said, ‘Even when there’s no major offensive going on, there’s a constant drain of manpower, from accidents and injuries.’

‘When do the Americans come in?’ Milner asked.

‘I can hardly expect them to do much before May or June at the earliest. And the Germans seem likely to attack in the spring. I must have more men.’

‘We will have to extend the conscription age,’ Lloyd George said. ‘We must take boys as soon as they reach eighteen, and send them abroad at eighteen and a half. And raise the upper limit from forty-one to fifty-one. There are plenty of perfectly fit men in their forties – some of them eager to get into uniform, I’ll be bound. We might take it as high as fifty-six if we need to.’

The snow had stopped by the time Edward stepped out into the street again. In the muted light, the pavements and rooftops glowed eerily under their white covering. It was bitterly cold. Lord Forbesson left with him, and they walked together to the end of the road. ‘Well, that went smoothly,’ he said. ‘You played your part well.’

‘It would have been nice to know I had a part,’ Edward complained. ‘Then I could have been prepared.’

‘No, no, you came off quite natural – just what we wanted,’ said Forbesson. ‘Rehearsal would have stilted you.’

‘Do you anticipate much resistance in the House?’

‘A few will see it as creeping socialism. I don’t like it myself, but with a war to fight, it can’t be helped. The important thing is for the lower classes to know their allocation of food is assured, see an end to this damned queuing.’ He glanced sidelong at Edward. ‘As for the other thing – the upper limit to the conscription age …’

‘I’m forty-eight. It never occurred to me I might be called up,’ Edward admitted.

‘I’m fifty-five,’ said Forbesson. ‘Not that they’d comb me out of the War Office. You won’t have to serve, either. You’re too important back home. Are you going back to the bank, now?’

‘No, the Treasury,’ Edward said. ‘A meeting about war bonds.’

‘There you are, you see,’ said Forbesson. ‘Can’t afford to send you to France. Have you had the letter about your knighthood yet? About the investiture?’

Edward felt a curious kind of shyness. He still did not feel he had done anything to earn a knighthood, when men were giving their lives in battle. ‘The ceremony is on the twenty-fifth of February,’ he said. ‘At Buckingham Palace.’

‘That’s what I heard. I believe the King will be taking it himself. It’s this new honour he thought up last year – Order of the British Empire. He’s frightfully keen on it. Honours for the fellers who’ve actually done something, not just Buggins’s Turn. He’ll want to have a little chat with you about your achievements. Better have a few words prepared.’

‘Thanks for the hint,’ said Edward.

Forbesson smiled. ‘Sir Edward Hunter, KBE. It sounds well! Is your good lady excited? I find the memsahibs usually set more store by these things than us chaps.’

‘I’m sure she is,’ Edward said. ‘But she was never one for showing her feelings.’

Ada let Beattie in, and said reproachfully, ‘Oh, madam, you’re all wet!’ It had been snowing again. She helped Beattie out of her coat with a tch tch.

Antonia came into the hall as Beattie was trying to take off her hat, fumbling at the pin with frozen fingers. ‘You didn’t walk from the station? You ought to’ve taken a taxi.’

‘There weren’t any,’ Beattie said. The truth was, she hadn’t even looked to see. She had hardly noticed the snow, but she saw now that her shoes were soaked through and her stockings wet to the calf. They would both want to fuss over her, and she didn’t deserve it. She didn’t deserve their love.

Antonia said, ‘You look so tired. You work too hard – and then the journey home. Was the train packed? Did you get a seat?’

‘No – yes – I don’t know,’ Beattie said. It was necessary to distract her attention. ‘You are the one who works too hard,’ she said. ‘You should be resting. Ada, has she had her feet up, as Harding said?’

The baby was due in April, and Antonia, in truth, looked the picture of health, her eyes bright and her skin glowing. But Ada who, like most unmarried servants, was intensely interested in pregnancy and childbirth, was successfully diverted, and said, ‘No, madam. I’m sorry to tell tales, but she was out at the canteen all day. She only got in half an hour before you. I was just going to bring her a cup of tea.’

‘Oh, bring me one too, will you?’ Beattie said. ‘Just what I need.’ That got rid of Ada, who bustled off, looking pleased – tea was the panacea for all ills – and she scotched Antonia by asking, ‘How’s David?’

Antonia answered at length as she followed Beattie into the morning-room. Because of coal rationing, they used it during the day, and the drawing-room fire was only lit after dinner.

‘He’s very low,’ she said. ‘He tries to hide it, but I know the signs. He’s had pupils all day, and it tires him, but it is better for him to have to make the effort, isn’t it, rather than brood?’

‘Is it Jumbo?’ Beattie asked, letting her tired body down into the chair by the hearth. What a miserable little fire! She stretched her cold wet feet towards the meagre warmth, hoping Antonia wouldn’t notice their state.

But Antonia was thinking about her husband. ‘He doesn’t say, but I think so.’

Jumbo had been David’s best friend at school and university, and they had volunteered together in the first month of the war. David was wounded in 1916; Jumbo had been killed in the autumn of 1917. The news had come just as David seemed to be getting better – married to Antonia, his health improving, walking a little more. Jumbo’s death had thrown him back into the gloom in which he had existed since shrapnel had shattered his femur and ended his war.

Antonia talked on. Though David was her first-born and best-beloved child, Beattie didn’t listen. She nodded and said, ‘Mm,’ at appropriate moments, and let her mind drift in exhaustion. It was something she was becoming skilled at. She had been all day at the 2nd London General, sitting by Louis’s bed, holding his hand while he talked. Her knees grew stiff and her back ached through sitting so long, but he did not like her to leave him for a moment. If Waites, his soldier-servant, had not brought her a cup of tea – God knew where he had scrounged it from – she would have had nothing to eat or drink all day.

He had been talking, talking, about South Africa, his plantation, and their future life there together. She didn’t always listen – he had said all of it before, more than once – but gazed at him, loving him, tracing his features with her eyes, remembering their past, grieving for his present helplessness, fretting about what was to come.

She had loved him since she was a young woman in Dublin, just come out, and he was a penniless subaltern up at the Castle. She had loved him madly, unreasoningly, longed for him desperately through twenty years of separation, marriage to Edward and six children; never thinking she would see him again. And then the lottery of war had thrown him into her path.

She had been helpless to resist him; they had pursued a passionate affair in the snatched moments when the army and her duties released them for a few hours. But after the war, he had said – after the war we will go away together, be together for ever. And she had always stopped him, unable to discuss it, unable to contemplate what that would do to Edward, her good and loving husband, and her children.

He had been shot through the head during a night action at Poelkapelle. Somehow he had survived, but the surgeons had removed one eye, and the other was now sightless, the optic nerve severed. He who had been so upright, strong, capable – quintessentially a man of action – was now disabled and dependent. Unaware of night and day, he waited in his own personal darkness for her to come and take his hand. She was all he had, he who had been fearless soldier, world traveller, pioneer and planter. As soon as he was discharged, from the hospital and the army, the decision would be upon her. How could she refuse him? He needed her more than ever. The moment she had dreaded, when she would have to face Edward and tell him, was approaching – screaming down on her like a shell, to blow her life to shreds.

When the time had come to leave for the day, he had clutched her hand harder than ever. His remaining eye was dark-blue – so beautiful! David’s eyes! – but blank, his face was as pale as carved wax. The outdoor tan of campaign had faded. In South Africa, she had caught herself thinking, he will grow brown again, riding about the estate. Oh dear God, South Africa! How could she do it – leave Edward, her children, her whole life?

How could she not?

‘You will come tomorrow?’ he had said.

And she had said yes, of course. ‘You need to rest now.’

‘Rest?’ he had said. ‘From what?’

She had found Waites hanging about outside in the corridor.

‘Oh, ma’am, I don’t know how to get through to him,’ he said, twisting his hands about. ‘He just won’t understand. I’ve tried to tell him, but it goes in one ear and out the other. Oh ma’am, can’t you tell him, make him see it?’

‘See what?’ Beattie asked. ‘Slow down. You’re not making sense. Tell him what?’

‘He keeps talking about South Africa, like I was going to go with him. I’ve looked after him for years, but I belong to the army. As soon as they discharge him, they’ll send me off somewhere else. I won’t have any say. But he thinks I’ll be staying with him. Oh, ma’am, I know he needs me, but I can’t help it. Can’t you talk to him, please? Make him understand?’

‘I’ll try,’ she said wearily.

She understood that thinking about South Africa was his way of keeping a grip on himself, through the chaos that had engulfed him. And it required him to assume the two people closest to him, her and Waites, would be there with him. Waites had no choice in the matter. And, in truth, neither did she. She must abandon her husband and children, her respectability, the whole structure of her life, because she could not abandon Louis.

‘I’ll try,’ she said again, patted Waites’s arm, and went home.

David did not come down to dinner, and Antonia decided to take hers on a tray with him, up in their sitting-room. After dinner, when Peter, the youngest, had gone to bed, Sadie and William went over to the table by the window to play a game of cards, leaving Beattie and Edward alone by the fire. It was a chance for them to talk – if they spoke quietly, they would not be overheard. In a married life blessed with six children, they had learned to conduct their intimate exchanges in that way, whenever and wherever they could. Now, however, it was the last thing Beattie wanted. She was minded to say she was going straight to bed, but could not for the moment drag herself out of the chair. And then it was too late, for Edward, who had been studying her averted face, said, ‘You look so tired, dear. Let me mix you a nightcap – it will help you sleep.’

He mixed her a whisky and soda, as he had used to – mostly soda – and brought it to her. His gentleness, his care for her, touched her unbearably. She looked at him with a kind of despair. ‘Why are you so good to me?’ she said.

He smiled. ‘You’re my wife. Why would I not be?’

‘Husbands aren’t always,’ she said, and took a gulp of the whisky. She disliked the taste. She preferred it mixed with sugar and lemon, but both were in short supply these days. But whisky and soda was like medicine to her – you took it for the effect, not the taste.

Now she was looking at him, she could not stop. She examined his features, so familiar she barely registered them any more. He was a pleasant-looking man, falling only just short of handsome, his nose and chin perhaps just a little too long. Dark of hair, brown-eyed, sallow-skinned – his beard coming through after this morning’s shave was a shadow around his chin and lips. The lips that had kissed hers many thousands of times. She shuddered inwardly at the memory – not in dislike, but in remembering the physical passion that had been between them. She had loved his body, enjoyed his love-making. And they had been good friends, on the whole, as much as husband and wife ever were. Everything had been going along comfortably, until the war. The war had shattered her peace. Her terror for David, when he had volunteered, terror that had proved wholly justified, and then Bobby – oh, Bobby, dead in France, never coming home – had deranged her. She had been unable any longer to give Edward anything, not mind, not body, often not even basic kindness. And then Louis had come back into her life.

And through it all, he had remained the same Edward, kind and good. She did love him, she did – but she was in a trap. Yes, a trap of her own devising, but that did not make it any better. She, like Waites, had no choice. He must go with the army. She must go with Louis. And Edward – Edward must be abominably, unjustly hurt. And David – oh God, David! – she must leave him behind, too.

Edward was speaking. She forced herself to pay attention.

‘… too much for you. I know you will say there’s a war on and we must all do our duty, but you need to take care of yourself too. You can’t help others if you break your own health. You must rest more.’

‘Rest won’t help me,’ she said, bleakly.

‘You must have some pleasure in life. A little treat now and then wouldn’t harm the War Effort. Lunch in Town. A shopping trip. The theatre – how would you like to go to the theatre? I could get tickets—’

‘I don’t think I could sit through a play. And then the journey home afterwards – the trains are so slow and so dirty …’

‘We could stay in Town for the night. Dinner and an hotel. It will be like old times.’ When he smiled, his face lifted that extra fraction into handsomeness. Words welled up in her heart. She wanted to tell him; to let everything burst out of her, the whole terrible truth, and have done with it. And while she struggled, he went on, very softly, ‘We haven’t been very close lately. It’s partly my fault – I’m so busy. But I want to take care of you, dearest. I can’t bear seeing you unhappy. Let’s make an effort to spend time together. The theatre, dinner – we could go away, just for a couple of days. I could make space in the diary …’

He wouldn’t stop now, she could see that, and she was tired, so tired. She must put an end to this. ‘That’s a lovely idea,’ she said. ‘We might manage it in a week or two. Let’s see. And now I must go to bed. I’m so very tired.’

He let her go this time, and she hurried away, feeling like Judas.

She fell asleep the moment her head touched the pillow; but as was often the way when going to bed too early, she woke from a profound sleep, thinking it must be morning, only to hear the clock in the hall strike eleven. She lay in the dark, wondering whether she would be able to sleep again; and her bedroom door slowly opened, making a slice of light from the passage beyond. One of the children? Peter was still young enough to seek comfort after a nightmare. David? Her mind jerked fully awake. Something wrong with David? But she heard no voices out there, no commotion.

‘Beattie?’

It was Edward. Now he came into the light and she saw him, in his dressing-gown. They hadn’t slept together since David volunteered. He had a bed in his dressing-room. What could he want with her? She hadn’t moved, and the light had not touched her yet – she could pretend to be asleep. She felt him cross the room, knew he was standing over her. His warm hand touched her hair, gently caressed her cheek. She could wake, let him into her bed, be held by him. He had always taken care of her. Every part of her ached to be comforted. But that would be the worst betrayal of all. He would remember, after she told him the truth, that she had dishonestly taken his comfort, and it would hurt him even more.

‘Beattie,’ he said again, but it was not a hopeful question. It was a sad and lonely word of departure. And he went away, quietly closing the door behind him.

‘Emily!’ Cook called out. She looked round impatiently. ‘Where is that girl?’

‘In the scullery,’ said Ada, coming back in from the dustbins. ‘Doing the knives.’

‘She should have finished ages ago. She’s so slow, she’d get passed by a snail with bad feet. I want her peeling the potatoes.’

‘It’s not easy, peeling potatoes with only one arm. I’ll do ’em for you later.’

‘I’ll give her the thick end of my arm if she doesn’t buck her ideas up,’ Cook said. ‘And I want ’em now, so’s I can boil ’em. I’m going to do ’em soteed for the master tonight, to cheer up the cold beef. He likes a sotee potato.’

‘I’ll peel ’em and boil ’em for you,’ Ada said, going out at the other end, ‘when I’ve done the beds. There’s plenty of time.’

Cook went stamping towards the scullery, muttering. Emily had left to become a munitionette, but had returned, begging for her job back, after she had been injured at the factory. The missus had kindly taken her in. Cook was sorry for her, of course, but there never was such a slow, dim-witted and fumble-fingered girl in creation. There was a man with only one arm who sold matches outside the station, and he was bright as a cricket. Even managed to tie his own shoelaces, while Emily, who had a second arm, even if it hurt, couldn’t even clean a few knives before day turned into night!

‘Emily!’ she said again, reaching the scullery door. And there was the wretched girl, not working, but sitting and staring into space with her mouth open, cradling the arm that was in a sling. ‘Well!’ said Cook – a word into which she could get a world of meaning and menace.

Emily jumped. ‘I’ve nearly done ’em,’ she protested. ‘Just resting me arm, so I was.’

‘I’ll rest you,’ Cook said automatically.

‘It hurts awful,’ Emily said.

‘So do my feet, but you don’t hear me complaining,’ Cook snapped. ‘You shouldn’t have gone for a munitionette. I warned you but, oh, no – you had to know better. And now look! You young girls are all the same. You never listen. Well, you’d better bring the rest of them knives out here and do ’em at the table, where I can see you.’

She had just got settled when Ada came back in. ‘Mrs David says Mr David’ll just take soup for luncheon.’

Cook sighed. ‘And I’d got a nice bit of fish for him. Soup’s not enough.’

‘And he probably won’t eat that,’ Ada said. ‘He hardly touched anything yesterday. Got no appetite at all.’

‘I expect his leg’s paining him.’

Ada nodded. ‘But he won’t admit it. Doesn’t want her to worry in her condition. But he’s at that Dr Collis Browne’s all day long. He told Ethel he’d dropped the bottle and spilled it and sent her out for a new one, but there wasn’t any stain anywhere. He’d drunk it all, in my opinion. Course, Ethel plays along with him. Whatever Mr David wants, he gets. He’s a ewe-lamb to her.’

Emily’s eyes filled with tears. Her arm hurt, but no-one cared. Mr David’s leg hurt, and everyone was sorry for him.

Cook looked across at her. ‘Look at the mess you’re making! And don’t use so much powder. It’s wasteful. Don’t you know there’s a war on?’

* * *

As she made her way from Chelsea station towards the hospital, Beattie found herself walking faster. However difficult things were, she longed to be with him. After half a lifetime of famine, it eased something in her simply to be near him. She carried a shopping-bag containing twenty Three Castles, two ounces of sherbet lemons, and a block of Trumper’s sandalwood shaving soap. She would make the giving of each last as long as possible – have him guess what it was, by smelling it, perhaps. Make a game of it, to wile away the tedium of blindness. And she had gone so far as to look through the newspaper at home before she left, so as to be able to tell him the main events.

She was beginning to be a familiar face around the hospital, and nodded to one or two people as she hurried through. He was no longer in the garden annexe, having been moved to one of the less acute wards – a preparation, she supposed, for being discharged. A date had not yet been mentioned, but she gained the impression that it could not be long in coming. Would the army send him to some sort of convalescent home to acquire the skills he would need to survive in a dark world? Or would they just discharge him and leave him to make his own arrangem

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...