- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

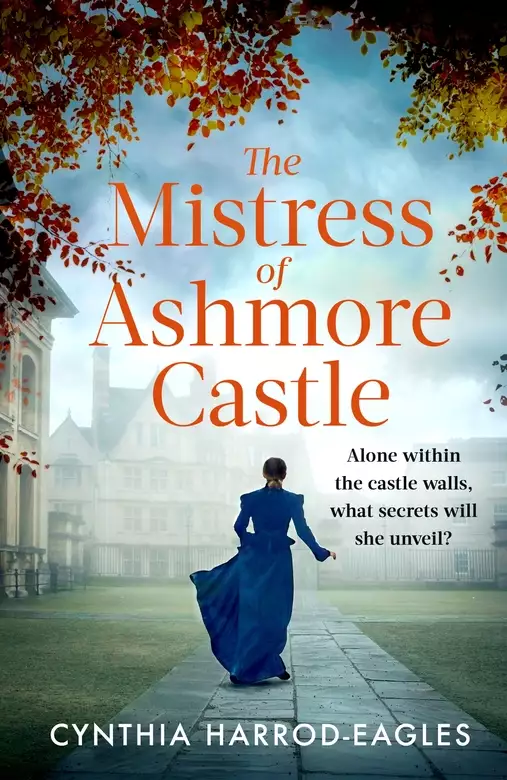

England, 1903. Giles, the Earl of Stainton, has fled from his stifling duties to resume his research in Egypt, leaving behind his wife Kitty, and his infant son. Kitty, still reeling from Giles' sudden departure, struggles to keep spirits high in the castle and establish herself as the true mistress of the house, an impossible task given how many secrets the inhabitants are hiding from her...The Earl's younger sisters, Rachel and Alice, are both pursuing forbidden romances, and his brother Richard begins a new business venture, spurred on by his clandestine lover. And below stairs, a shocking crime sends distrust rippling through the staff. Kitty must draw on her strength to keep the castle from crumbling around her, but with her marriage to Giles left uncertain, and a surprise of her own to conceal, can she ever take her rightful place as true head of her household?

Release date: August 3, 2023

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 82500

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Mistress of Ashmore Castle

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

The family

Giles Tallant, 6th Earl of Stainton

— his wife Kitty, the countess

— their baby son Louis, Lord Ayton

— his eldest sister Linda, married to Viscount Cordwell

— their children Arabella and Arthur

— his brother Richard

— his sister Rachel, age 18

— his sister Alice, age 17

— his widowed grandmother, Victoire (Grandmère)

— his grandfather’s half-brother Sebastian (Uncle Sebastian)

— his widowed mother Maud, the dowager countess

— her brother Fergus, 9th Earl of Leake (Uncle Stuffy)

— her sister Caroline, widow of Sir James Manningtree (Aunt Caroline)

— her sister Victoria (Aunt Vicky), Princess of Wittenstein-Glücksberg

— her cousins Cecily and Gordon Tullamore

— their children Angus, Beata, Fritz, Gussie, Ben, Mannox, Mary

The male servants

Moss, the butler

Crooks, valet to Mr Sebastian

Speen (deceased), former valet to Mr Richard

Afton, new valet to the earl

Footmen William, Cyril, Sam, James (Hook, former valet to the earl)

House boys Wilfrid, Eddie

Peason, head gardener

Allsuch, under gardener

Cox, Wilf, gardeners’ boys

The female servants

Mrs Webster, the housekeeper

Miss Hatto, maid to the countess

Miss Taylor, maid to the dowager

Housemaids Rose, Daisy, Doris, Ellen, Mabel, Tilda, Milly, Addy, Ada, Mildred

Dory, sewing maid

Mrs Oxlea (deceased), former cook

Mrs Terry (Ida), new cook

Brigid, Aggie, Debbie, kitchen maids

Nanny Pawley

Nursery maid Jessie

In the stables

Giddins, head man

Archer, groom to the earl

Josh Brandom, groom to the young ladies

Stable boys Timmy, Oscar, George

Coachmen John Manley, Joe Green

On the estate

Markham, land agent

Adeane, bailiff

Moresby, solicitor

Saddler, gamekeeper

Gale, estate carpenter

Axe Brandom (brother to Josh) woodsman

In the village

Dr Bannister, rector of St Peter’s Church

Physician, Dr Arbogast

Police Sergeant Mayhew

Police Constable Tom Holyoak

Miss Violet Eddowes, philanthropist

— her cook Mrs Grape, her maid Betty

IN MARKET HARBOROUGH

Nina, Kitty’s best friend

— her husband Joseph Cowling, an industrialist

— Decius Blake, his right-hand man

— her housekeeper Mrs Deering

— her maid Tina

— her groom Daughters

— her friend and neighbour Bobby Wharfedale

— Bobby’s husband Aubrey

— Bobby’s brother Adam Denbigh

— her friend Lady Clemmie Leacock

IN LONDON

Molly Sands, piano teacher, once lover of the 5th earl

— Chloë, her daughter

Sir Thomas Burton, impresario, Grandmère’s cicisbeo

Henry ‘Mawes’ Morris, cartoonist, Mr Cowling’s friend

— his wife Isabel and daughter Lepida

December 1903

As the butler, Moss, walked down the room, everyone could see that there was a letter with a foreign stamp on his silver salver. But everyone was too polite to stare, and carried on eating breakfast as if nothing interesting were happening.

Moss stopped by Kitty, bowed, and murmured. She took the envelope and, while he paced slowly back, opened it, drew out the sheet and read it. It was only when she folded it back into the envelope without comment that the patience of her sister-in-law Linda snapped. She glared at Kitty, and said, ‘Well? I suppose it is from Giles. What does he say?’

‘Dear,’ Linda’s husband, Lord Cordwell, admonished gently.

Even Kitty’s mother-in-law, the dowager countess, not known for tact, drew a sharp breath of disapproval.

Linda shrugged it off. ‘Oh, don’t pretend you don’t all want to know,’ she addressed the room. ‘Kitty! What does he say?’

Kitty didn’t answer at once. Her throat had closed. She hadn’t expected to hear from her husband. Even if he had time to write, and had anything he wanted to say to her, she didn’t suppose there were postboxes in the Valley of the Kings. Her heart had jumped with painful joy when she saw the letter: the disappointment was proportionately great.

‘He says one of the other archaeologists at the dig had to come back to Paris on business, and offered to post letters for everyone there,’ she said at last.

‘Oh, don’t be tiresome,’ Linda said. ‘Is he coming back for Christmas? That’s what we want to know.’

Alice and Rachel both looked up at that point, hope in their faces. But Richard said, ‘It’s the best part of two weeks’ travelling to get back here, and he hasn’t been gone long. It wouldn’t be worth his while.’

Linda gave a snort of disapproval. ‘It’s disgraceful, going off like that. It looks so outré. People will talk if he’s not here for Christmas. But that’s typical of Giles – he thinks of no-one but himself.’

Kitty pushed back her chair abruptly and got up. Linda threw the rest of the rebuke at her departing back. ‘I blame you, Kitty! You’ve had plenty of opportunity to develop a proper influence over him. If you had exerted yourself, we shouldn’t now be in this position.’

‘Please may I have the stamp, Aunty Kitty?’ Linda’s son Arthur pleaded urgently, but had no reply.

The dowager shrivelled Arthur with a look, and said to Linda, ‘I cannot understand why the children should eat with us at breakfast. None of my children was allowed down until they were twelve.’

‘It was Kitty’s idea,’ Linda said sulkily. ‘It’s a modern thing, I suppose.’

‘It’s so that they can learn how to behave at the table,’ Richard said, but the veiled rebuke slid off her. She might notice being hit with a brick, but subtlety was wasted on her.

‘Stuff and nonsense,’ said the dowager to Richard. ‘That is what a nanny is for, to teach them manners. And until they have acquired them, they should remain in the nursery. Why did you not bring their nanny with you?’ she asked Linda.

‘Oh, she left suddenly, just before we came away,’ Linda said, buttering a piece of toast so fiercely it shattered. The fact was that they couldn’t afford a nanny. The Cordwell finances were in a perilous state, and Linda was hoping for a lengthy stay at Ashmore Castle to tide them over a thin patch.

Cordwell sighed so penetratingly that Sebastian, who had a shrewd idea how things stood at Holme Manor, felt sorry for him, and sought to distract him. ‘What do you say to taking a gun out this morning, Cordwell? We could walk down to the Carr and see if there are any duck.’

While they were discussing the possibility, Richard slipped out and went looking for Kitty.

In the Peacock Room, which she had taken as her private sitting-room, Kitty was standing at the window, staring out at the grey winter day. The cloud hung low over the woods like mist; nothing moved but rooks, scraps of black blowing above the trees.

On the wall beside the window was the pencil-and-water-colour likeness of Giles that Alice had done, which he had had framed as a present for her. It showed him three-quarter profile, looking away pensively into the distance. It was appropriate, she thought: his mind, his heart, would always be somewhere else.

She had shed all her tears in the days after he had left for Egypt to join friends at a dig. Archaeology was his passion, as she had always known; but it was his parting words that had crushed her. He had said he felt stifled at home, that he needed to get away. She feared that she was one of the things he wanted to get away from. At any rate, she had no power to keep him with her. She’d had to realise that he did not love her as she loved him. His wife, his child, his home, his family, together had less pull than the dusty sarcophagi and crumbling bones of long-dead strangers.

She heard someone come in behind her, and knew from the aroma of the Paris Pearl lotion he used after shaving that it was Richard. He came up behind her and placed a light hand on her shoulder.

‘Poor Pusscat!’ he said. ‘Don’t cry any more. My sister’s an ass, and there’s nothing to be done about her.’

‘I’m not crying,’ Kitty said.

‘But you sound as though you might. There’s nothing to be done about Giles, either, you know.’ She turned to face him, showing her eyes bright but dry. ‘What did he say in the letter, my impossible brother?’

‘That the weather was tolerable, the insects not too troublesome, the dig going well, and they think they are on the brink of exciting discoveries.’

‘Abominable! Married to the prettiest woman in England and not one tender word for her?’

‘Will people really talk when he’s not here for Christmas?’ she asked.

‘Can’t think why they should,’ he said. ‘In his position he can do whatever he wants. Of course, people would generally prefer an earl to go in for the traditional sins: loose women and high-stakes gambling, like my father – who was much admired, by the by. But if old Giles can’t quite rise to full-blooded vice, embracing eccentricity is the next best thing. The only really shocking thing would be for him to behave with Victorian propriety.’

‘You’re talking nonsense to cheer me up,’ Kitty said, beginning to smile.

He gave her a look of shining innocence. ‘Not a bit! Look at our dear old King Teddy. Thoroughly naughty before he came to the throne, and everyone loves him for it. They wouldn’t feel the same about him at all if he had comported himself like a respectable bank clerk from Sidcup. Now, what we must do is dedicate ourselves to the cause of cheering you up. We should throw the most tremendous Christmas ball.’

‘A ball? Really?’

‘Really! Let’s see . . . It should be on the Saturday before Christmas. The nineteenth.’

‘But that’s so close – everyone will already be engaged.’

‘They’ll cancel, for a ball at Ashmore Castle,’ he said confidently. ‘We’ll ask a dozen people to stay for it, and give them a shoot on the Sunday. I’ll arrange that part of it with Adeane and Saddler. And invite everyone in the neighbourhood for the dancing.’ He looked around. ‘You must have paper and ink here. Yes, fetch them, then, and we’ll start making lists. Then you can talk to Mrs Webster while I go and see Adeane.’

‘I’m so glad I bought new mattresses for all the beds,’ she said, crossing the room to her escritoire.

‘The mattresses are the essential element,’ he assured her. ‘It’s what people will principally come for.’

She smiled. ‘You’re absurd.‘

Mrs Terry had been cook at Ashmore Castle for only seven months. She had been just plain Ida, the head kitchen-maid, under the previous cook, Mrs Oxlea. But after Mrs Oxlea’s shocking death, she’d had to take over on an emergency basis. She had been doing a lot of the work anyway – Mrs Oxlea had been a drinker – and she’d long had ambitions. When Mrs Webster, the housekeeper, had relayed the mistress’s enquiry as to whether she would like the post permanently, she’d been glad and grateful.

Everyone seemed to think she had done pretty well. But there had not been any major entertaining until now. A ball! And people to stay for it as well! It was a completely new challenge.

Mrs Webster had come straight to see her, before the plan had been officially announced. The news had reached her in the usual roundabout but effective way: Richard had gone from Kitty to see Uncle Sebastian, who had been in his room. Sebastian’s valet Crooks had been bumbling about in the background so could hardly help overhearing, and Crooks had lost no time in telling Mrs Webster.

Mrs Webster had no doubts about her own ability to cope, but she realised that Ida would need encouragement. ‘The mistress will send for you, and of course you must pretend it’s all news to you, but it will be a good thing to have your plans ready, so that you can seem calm and confident.’

Ida was not calm and confident yet. ‘A dozen people to stay! Plus the family.’

‘Plus their servants, don’t forget. It’s a lot extra, but Brigid and Aggie can do the cooking for the servants’ hall. Don’t worry about that.’

‘What do people have at a ball? Isn’t there always a supper?’

‘A buffet,’ Mrs Webster said. ‘You can make most of it ahead of time. Lobster and oyster patties, bouchées à la reine, that sort of thing. A glazed ham. A cold sirloin for the gentlemen. Soft rolls—’

‘When will I have time to make those?’

‘Buy them in,’ Mrs Webster said briskly. ‘Toller’s in the village can supply them, and nobody will know the difference.’

‘If you think it’s all right . . . What else?’

‘Fruit. Whatever you can get at this time of year – the arrangement is everything. And some kind of sweet. A coffee blancmange, perhaps. You can make that ahead, too. We’ve got a lot of little glass custard cups somewhere – it’d look pretty in those. And then white soup for the end of the ball.’

‘And there’ll be a dinner before the ball, I suppose?’

‘They won’t want too much before dancing. Four or five courses, and you can keep it simple. Then there’ll be the shooting luncheon on Sunday, and dinner on Sunday night.’

‘And breakfasts.’ Ida put her hands to her cheeks, contemplating the mountains of food she must prepare. Her voice wavered. ‘However will we manage? Oh, Mrs Webster!’

‘You said you wanted the job,’ Webster said briskly. ‘Now here it is. You’ll need more girls, that’s obvious, but the mistress has already said I can hire anyone we need, and that includes in the kitchen. Brace up, Mrs Terry. You don’t have to cook every single thing yourself, you know. You’ll be like a general at a battle, giving orders to the troops. Of course,’ she added slyly, half turning away, ‘if you really don’t think you’re up to it . . .’

‘Oh, I’m up to it all right,’ Ida said quickly. ‘Don’t you worry about that. I’m going to be the best cook of any big house in the country! They’ll talk about me in years to come. I’ll be famous – Mrs Terry of Ashmore Castle, they’ll say. And when I’m old I’ll write my own book, like Mrs Beeton, and everyone’ll go to it for reference.’

‘That’s the spirit,’ Mrs Webster said.

The old schoolroom at the top of the house, which was now a sitting-room for the young ladies, was pleasantly warm. Since Kitty had taken over the direction of the house, there had always been a fire lit for them – unlike the days of economy under their mother.

Alice was sitting on the floor, sketch-pad against her knees, drawing Rachel, who was sitting on the window-seat staring dreamily out of the window. Alice had asked her to loose her hair, and it fell in long coils over her shoulders, while the light from the window threw interesting planes and shadows into her lovely face. It was, Alice thought, going to be a nice piece.

The dogs, Tiger and Isaac, were sprawled in front of the fire, giving an occasional groan of comfort. Linda’s children, Arabella and Arthur, were quiet for the moment, working on a jigsaw puzzle of the map of Europe, which Alice thought ought to keep them busy since she happened to know that half of Belgium was missing.

Rachel gave a sigh, and Alice thought she was looking particularly pensive. She had been travelling with her mother for most of the year, going to parties and balls and meeting young men, and Alice thought it was most likely that she had fallen in love with someone. She had been in love the year before with Victor Lattery, a most unsatisfactory young man – but at the time, he was almost the only one she had met, and Rachel was the sort of girl who would always be in love with someone.

So to be kind to her, Alice said, ‘You look as though you’re in a dream. What are you thinking about?’

‘The ball, and what I shall wear,’ said Rachel.

‘Oh,’ said Alice blankly. She wasn’t ‘out’ yet, and much preferred riding to dancing.

‘I hope Mama doesn’t make me wear the white organza again,’ Rachel went on.

‘Richard’s trying to persuade Kitty to wear white – Daisy heard Miss Taylor talking about it.’

‘But Kitty’s married,’ Rachel objected. ‘Married women don’t wear white.’

‘Don’t frown – I’m doing your face. Yes, but you know Richard, always trying to shock. He says a countess can do as she likes, and that with Kitty’s colouring she’ll look stunning in white.’

Rachel sighed again. ‘I’m so fair it doesn’t suit me.’

Alice agreed. ‘Next to Kitty, you’d look like two penn’orth of cold gin.’

Rachel wrinkled her nose. ‘Where did you get such a dreadful expression?’

Alice didn’t want to say she’d heard Axe Brandom use it. ‘Oh, it’s what the grooms say,’ she said vaguely.

‘Well, don’t let Mama hear you.’

‘Don’t look disapproving – still doing your face.’

‘You spend too much time in the stables. And you’ll never get a husband if you use coarse phrases like that.’

‘I don’t want a husband,’ Alice said, as she had said many times before, whenever she was rebuked for being unladylike, or having untidy hair, or sitting on the floor, or whatever other way she had fallen short of the maidenly ideal.

‘Well, you surely can’t want to stay here all your life,’ said Rachel.

‘Why not? I can’t see how I’d be happier anywhere else.’

‘I like it here,’ Arabella said, startling them both – they hadn’t realised she’d been listening. ‘I’d like to stay for ever. I don’t want to go home. Our house is like two penn’orth of cold gin.’

‘Two penn’orth of gold chin,’ Arthur echoed importantly. ‘It’s nasty and smelly.’

‘Arthur! Don’t say such a thing!’ Rachel said.

‘It is!’ Arthur averred. ‘Smelly-welly-jelly! I hate it! I want to stay here.’

‘Me too!’ said Arabella. ‘Can we go riding this afternoon, Aunty Alice?’

‘Ooh, yes. And can I ride Biscuit?’ Arthur said, bouncing on the spot. The dogs woke and raised their heads to look at him, wondering if the movement heralded a walk.

‘No, he has to have Goosebumps, doesn’t he, Aunty?’ Arabella objected quickly. ‘I always have Biscuit, cos I’m older and I can ride better. Arthur’s only a baby.’

‘I’m not a baby!’

‘You are!’

’Well, you fell off yesterday! I’ve not fallen off for ages.’

‘I won’t take either of you if you squabble,’ Alice said. They fell silent and, under her stern gaze, went back to the puzzle. The dogs flopped back again. Next to a walk, toasting at the fire was their favourite occupation.

Rachel gave her a look that said, Now you see what staying here all your life would mean. You’d be the spinster aunt.

Alice continued working. She was rather looking forward to the children going home, because she did tend to get stuck with them. She felt sorry for them, but having them tagging along meant she couldn’t go and see Axe in his woodman’s cottage up in Motte Woods. She missed those visits. She missed Dolly, his terrier, and the cats, and Della, his beautiful Suffolk Punch mare, and Cobnut, the rescued pony she had named, and the various injured or orphaned animals he had from time to time.

Most of all she missed Axe. And she wondered . . . Her hand slowed and stopped as her thoughts went travelling. Last time she had visited there had been a strange, palpitating moment when she had thought he was going to kiss her. He had stood so near, stooped his big golden face towards her, and everything in her had reached up to him, like a flower reaching for the sun. But then he had straightened up and turned away, and afterwards had been almost gruff with her. And insisted she left as soon as she had drunk her tea, saying it was going to snow and she must get home before it broke.

The snow hadn’t lasted long, and was followed by a thaw; but then Linda had arrived with the children, tying her down, and she had not seen Axe since. Christmas was coming, and it would be impossible to get away for ages. She missed him. And she wondered . . .

There was a tap on the door, and Ellen, one of the housemaids, came in. ‘Her ladyship wants to see you, Lady Rachel.’

‘Which ladyship?’

‘Your mother, my lady.’

Rachel got up obediently, straightened her skirt and was heading for the door.

‘Your hair!’ Alice cried.

Rachel hated to be told off, and her mother would object to her appearing in that fashion. She looked frightened. ‘I’d forgotten it was down!’

‘Let me, my lady,’ Ellen said. With some clever twists and a few pins gleaned from Alice and Arabella, she got it into a kind of chignon. ‘There. Not perfect, but it might pass on a dark night, as they say.’

‘Oh, thank you, Ellen! How clever you are! How did you learn to do that?’

‘Miss Hatto showed me, my lady. And Rose lets me practise on her sometimes. I’d like to be a lady’s maid one day. And if I can do hair, I can attend visiting ladies that don’t have their own maid, and maybe one day—’

‘Mama’s waiting,’ Alice reminded her sister; and Rachel fled.

Ellen followed her out. Alice turned the pages of her sketch-pad. She came to a pencil sketch she had done of Axe, head bent over a piece of harness he was mending. Lovingly she added some more shading, deepening the chiaroscuro. She could have drawn him from memory by now, but it was so much more satisfying to have the subject before her. Perhaps if she could slip away from the children for a few hours . . . She wasn’t their governess, after all. Surely someone else could watch them.

‘Aunty Alice, can we go riding now?’ Arabella broke into her thoughts.

‘Riding, riding, riding!’ Arthur shouted, bouncing again, and waking the dogs fully. They got up and stretched, and stalked towards Alice with suggestive smiles. They were delighted to find a human face at tongue level for a change.

‘All right,’ Alice said, sighing, fending them off, and rising. ‘Go and get changed.’

‘Hooray!’ said Arabella. ‘We’ve finished the puzzle, only there’s a piece missing.’

‘Puzzles are smelly,’ Arthur crowed triumphantly. ‘Puzzles are penn’orth of cold gin.’

Alice said, ‘If you mention “cold gin” once more I shan’t take you at all. And stop saying “smelly”.’

Arthur clapped his hands over his mouth at the threat. Arabella did the same, but they both shook with giggles behind them.

Mrs Webster found Moss, the butler, in the glass-closet in a sort of slow bustle that spoke more confusion than activity. What was wrong with him these days? she wondered irritably. Was he getting too old? Was he drinking – well, all butlers drank, but more than usual?

He looked up as she appeared at the door. ‘We haven’t had a ball for such a long time,’ he said. ‘And such short notice! There’s so much to do, and no time to do it. I hardly know . . . People staying, as well – and a shoot on Sunday.’

‘Everything will get done in its turn,’ said Mrs Webster, firmly.

‘But you have not considered. The ballroom, for instance, so long unused – we don’t know the condition of the floor!’

‘Don’t you remember, we used that firm in Aylesbury last time. They do everything – test the floor, clean and chalk it, tune the chandeliers. They hire out rout chairs as well, and tables for the card room. Mr Richard has already spoken to Giddins about the visiting horses and to Adeane about the shoot. I’ve spoken to Mrs Terry and she has the menu in hand, and I am hiring extra maids to clean the rooms – they arrive tomorrow. We’re short of good sheets, but I’m putting the mended ones on the family’s beds and I’ve ordered new ones from Whiteleys – they’ve sworn they’ll be here by Monday.’

‘Dear me,’ Moss murmured feebly. ‘I don’t know how you’ve managed to do so much already.’

‘Method,’ she said unkindly. ‘If you apply it to any task, order will result. There is never anything to be gained by panicking.’

Moss was hurt. ‘I never panic.’

‘There isn’t so very much left for you to do,’ Mrs Webster went on briskly. ‘Mr Sebastian will consult you about the wine, and you’ll need to talk to Giddins about the transport for the shooting luncheon and for those who want to go to church. Adeane and Saddler will see to the beaters, and loaders for the gentlemen who don’t bring their own. You’ll have his lordship’s guns ready for Mr Richard?’

Moss reached for his dignity. ‘Of course,’ he said, with faint reproach. ‘What was it you wanted to speak to me about? I am rather busy.’

She came in fully and closed the door behind her. ‘I want to talk to you about James.’

‘Ah,’ said Moss.

‘I don’t know what his lordship was thinking, demoting him from valet to footman.’

‘He refused to go to Egypt with his lordship,’ Moss said, with deep disapproval. ‘A shocking impertinence, and a dereliction of duty.’

‘I know all that,’ Mrs Webster said impatiently. ‘But why on earth didn’t he just dismiss him? Now Mister Hook has gone back to being merely James, at half the wages. He’s like a festering sore in the servants’ hall. You’ve surely noticed his attitude?’

‘He always was sharp-tongued,’ Moss agreed, ‘but he’s worse now.’

‘He criticises everything you do. Pretending it’s in a spirit of helpfulness, but he’s really just trying to diminish you in the eyes of the other servants.’

‘I’m sure your authority is sound, Mrs Webster,’ Moss said, bewildered.

She gave an exasperated sigh. ‘When I say “you”, in this context, I mean you, Mr Moss.’

‘Oh!’ said Moss.

‘He’s after your job. It’s unacceptable that he talks behind your back. Quite apart from your welfare, it unsettles the other servants. What are you going to do about him?’

‘You know it’s not in my gift to sack him,’ Moss said unhappily.

‘I think it is. He’s not a valet any more. The male servants apart from the valets come under your authority.’

‘But with his lordship away . . . If he’d wanted him gone, he’d have sacked him himself. Perhaps there is some reason . . . Say his lordship wanted him to stay, it would upset him to come back and find . . . Perhaps you could speak to her ladyship. Or Mr Richard.’

Mrs Webster made an impatient sound. Moss looked away, let his eyes rove about the closed cupboards in search of escape. All this unpleasantness . . . It tired him out. He wished Mrs Webster would go away. He had always disliked James, even before his elevation, disliked the way he looked at the maids. He thought about Ada, the new little housemaid, white as a lily, delicate as a butterfly. He longed to escape this unpleasant conversation and seek her out, find some excuse to talk to her and have her look up at him in the respectful, admiring way that swelled his heart. The thought of James looking at her, still less touching her . . . ! He wanted to protect her against the whole world. Little Ada, with her long neck like the stem of a flower . . .

‘If you’re not going to dismiss him,’ Mrs Webster said sharply, recalling him to the present, ‘at least speak to him, put him in his place. He’s already talking about valeting any gentleman who comes to stay without his own man. He’s fourth footman now. It’s not for him to put himself forward.’

‘Well, he is experienced,’ Moss began.

‘You know he’s only interested in the tips. To allow him to valet a guest would be tantamount to rewarding him for refusing to accompany his lordship. And I don’t think that’s what his lordship had in mind – do you?’

Moss drew himself up. ‘If any gentleman needs a valet, I shall decide who it is to be. I will speak to James. He takes too much upon himself.’

‘You should dismiss him,’ Mrs Webster said.

‘I will deal with the situation. Leave it to me,’ Moss said loftily, and she gave him a hard look, and went away. Moss waited until her footsteps had died away, and went back to his own room, where he could close the door. There was almost a quarter of a bottle of claret in his cupboard, left in the decanter last night, which he had poured back into the bottle before the decanter was washed. Obviously you couldn’t send up a small amount like that again, and it was a sin to waste it. It was the butler’s perquisite, a reward for a lifetime’s devotion to the study of wine in his master’s service.

He would never, of course, touch the spirits.

The climate in Egypt was reckoned to be perfect in December for digging, still hot by English standards, but not uncomfortably so; a little rain on the coast but none inland. Nevertheless, there was a general inclination to stop for a day or two at Christmas. Most of the archaeology community was taking the train into Cairo to stay at hotels or with friends and enjoy the delights of civilisation. Giles, having been on site only for a few weeks, was already impatient at the idea of suspending work, but an invitation from Lord Cromer, the consul general, to a ball on Christmas Eve could not be lightly dismissed.

‘Why me?’ he complained, showing the invitation to his friends Talbot and Mary Arthur. ‘He hasn’t asked you or Max.’

‘You’re an earl,’ Mary Arthur said. ‘I expect he has to impress Egyptian officials. And the French diplomatic circle. Perhaps even merchants.’

‘Well, I didn’t come all the way out here to start this nonsense again – balls and dinners, indeed!’

The letter from Lord Cromer’s aide, Guy Bellamy, which accompanied the invitation, explained that as the consulate-general building was only leased and not very commodious, the ball and its preceding dinner were to be held in a private mansion, lent for the occasion by a Mr Walton Antrobus. A handwr

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...