- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

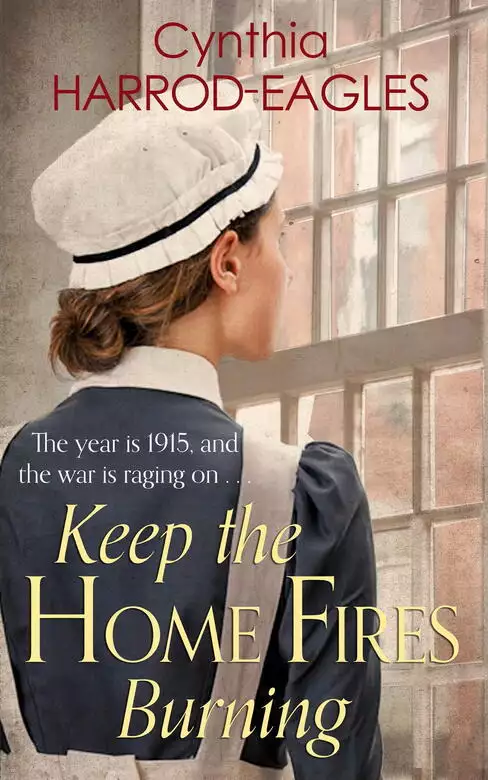

The year is 1915, and the war is raging on . . . The war was not 'over by Christmas' after all and as 1915 begins, the Hunters begin to settle into wartime life. Diana, the eldest Hunter daughter, sees her fiance off to the Front but doesn't expect such coldness from her future mother-in-law. David's battalion is almost ready to be sent to the Front, but how will Beattie's fragile peace of mind endure? Below stairs, Ethel, the under housemaid, is tired of having her beaux go off to war so she deliberately sets her sights on a man who works on the railway, believing he won't be allowed to volunteer. Eric turns out to be decent, honest and he genuinely cares about Ethel - is this the man who could give her a new life? The Hunters, their servants and their neighbours soon realise that war is not just for the soldiers, but it's for everyone to win, and every new atrocity that is reported bolsters British determination: this is a war that must be won at all costs. Keep the Home Fires Burning is the second book in the War at Home series by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles, author of the much-loved Morland Dynasty novels. Set against the real events of 1915, this is an evocative, authentic and wonderfully depicted drama featuring the Hunter family and their servants.

Release date: June 18, 2015

Publisher: Sphere

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Keep the Home Fires Burning

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

There was little movement beyond the occasional flight of birds from one battered stand of trees to another, or a wisp of smoke from one of the few farm cottages still occupied, climbing reluctantly into the damp, foggy air, grey on grey. The thousands of soldiers who invested the landscape were invisible, gone to ground. On both sides they had dug in to try to make the best of things, shore up their defences and wait for better days.

There wasn’t much to do in the trenches. Apart from dawn and dusk stand-tos, there were only routine inspections and maintenance duties. For the rest of the time Jack Hunter read anything he could lay his hands on (books were precious in the front line, but also fragile in the relentless damp) and wrote long letters to his wife. In fact, it was more like one long letter, sent off in sections as chance, the postal collection or running out of paper dictated.

I’ve been re-reading your account of Christmas [he wrote on New Year’s Day]. Glad to know London is still humming. I can just imagine all those restaurants and clubs bursting at the seams, the dances and parties, the taxi-cabs crammed with revellers.

The top brass were furious about our ‘Christmas Truce’, but our colonel was glad of the chance to mend the barbed wire, bail out the trenches and bring in the dead. They’ve been mouldering out there since November, making us all feel rather fed up. Orders from on high say ‘no more fraternisation’; we must all shoot to kill from now on. In fact, hardly anyone shoots at all. What Tommy in his right mind would poop off at an invisible enemy, when it means hours of cleaning the rifle afterwards? I expect the Boche feel the same, because they’ve been quiet all week.

So we were surprised last night when there was a sudden ferocious fusillade from the trenches opposite. Couldn’t think what had come over them, unless they had some choleric general visiting. There was nervous speculation on our side about a new campaign of night raids, until some wise person (yes, it was me!) remembered that our 11 p.m. is their midnight. They were ringing in the New Year, and courteously firing well above our heads so that we shouldn’t get the wrong idea. An hour later we returned the compliment, after which it all went quiet again.

By one of those unsought miracles familiar in army life, we had a new pump delivered despite not having asked for one. It is much more efficient than the old one and we are finally pumping out more water than is coming in, so we can see the duckboards again. I have a decentish dugout, and only two more days in the front line, and two in support, before I can get back to the heaven that is Poperinghe, and a bath. The child Jack would never have believed how much the adult Jack would long to be in hot water!

Gibbs has just poked his head in to say that, in honour of the New Year, the commissariat have sent up currant duff with dinner, which has just arrived. Also he has acquired a piece of cheese (best not to ask how) to go with the thimble of port he’s been saving for just such an eventuality. So tonight I can report I am fairly comfortable and shall be well fed, and inconvenienced only by the dampness of the writing-paper. That and being so far away from you, dear love. Not much to do but sleep (good!) and reflect Janus-faced (not so good!) as one is obliged to do at the opening of a new year.

It has been a strange war so far – mistakes, setbacks, heroic exertions, swings of fortune, desperate dashes, tremendous stands. Our tiny army has cheated the mighty German machine of what it must have thought was certain victory. And now here we are, where we are, dug in, waiting to see what happens. It occurs to me that the war we all expected and prepared for is actually over. We fought it, and no-one won. Now we are facing a new, different, war, one that no-one imagined, and that no-one really knows how to fight. We shall find out, I suppose, when spring arrives and we come out of hibernation. Let’s hope 1915 will see a victory as unequivocal as 1815. Then I can come home to you and sink back into the delicious reverie that is our marriage. Dear love, for nothing less than war would I have broke that happy dream, as Donne almost said.

The whole of Northcote was wild with excitement over the engagement between Charles Wroughton, Viscount Dene, and Diana Hunter. Diana had been the acknowledged local beauty for too long for anyone to resent her success. Besides, the Wroughtons had always been viewed as rather stand-offish, and it had been assumed that Charles would eventually marry a titled girl, so it was gratifying that one of their own, so to speak, had conquered the citadel. Visits of congratulation to The Elms began the very next day, and went on for the whole week before Christmas. There were even newspaper reporters, polite at the front door and shifty at the back, looking for comments and the ‘story’ that would appeal to their readers.

The servants were thrilled about the engagement, and no amount of extra work answering the door and carrying in trays of tea for visitors dampened their enthusiasm. Cook and Ada were talking about making a scrap-book; Emily sang ‘They Didn’t Believe Me’ over and over as she scrubbed floors; Nula had started collecting illustrations of bridal gowns from the magazines and making her own drawings.

Beattie dispensed tea, received congratulations, answered questions, and tried to protect her daughter from the more impertinent intrusions. She found it hard to tell what Diana was thinking. Charles had had to go straight back to his regiment, which lent an air of unreality to the rejoicing. It was no surprise that Diana drifted about like a sleep-walker. Kind visitors had murmured that she was in a daze of bliss; to Beattie it seemed more like shock.

Boxing Day at Dene Park had been a difficult occasion. The earl, who had a certain efficient charm, raised a toast to ‘our lovely future daughter-in-law’, but Lady Wroughton had spent so much of her life putting people in their place that it was hard for her to stop now. Her kindest address to Diana had been an undertaking to ‘see what they could do about making her an asset to the house’.

In addition, there had been Charles’s sister, Caroline, and her husband, Lord Grosmore, who seemed unflatteringly astonished about the whole thing; Charles’s younger brother, Rupert, who managed to make a smile look like a sharp weapon; and a number of Wroughton relatives, who simply didn’t know how to talk to people they didn’t know and, worse, had never heard of. The older ones appeared to be wondering how on earth such people had managed to get into the house.

As the Hunters descended from the motor-car that had been sent for them, Beattie had seen her daughter stop and look up at the portico. With its four massive Corinthian pillars and stark, undecorated pediment, ‘imposing’ was the adjective most often used by guidebooks. Dene Park dated from 1680, and the Wroughtons of the time had chosen the least fancy of Palladio’s designs, with the intention of intimidating visitors rather than enchanting them. As Diana stared, rather white, Beattie could guess her thoughts. To Charles, it would just be the entrance to his home, and he would notice it no more than Diana noticed the porch over the front door at The Elms. The gulf between their two worlds was there before them, encapsulated in solid, undeniable Portland stone.

It was not just Charles, not just the earl and countess and sundry other stiff relatives, but the whole of his world: friends and endless tiers of cousins all brought up like him, with habits and language and expectations quite different from those of a banker’s daughter. Not just Dene Park but a house in Norfolk, an estate in Ireland, a hunting-box in Leicestershire and two houses in London. How was Diana, their Diana, to fit in with all of that?

Beattie did not confide her doubts to her husband. Dene Park held no fears for him: he dealt daily with the mighty and visited many great houses in the course of business. Besides, he knew the earl – one of his clients – tolerably well. He had even been invited once or twice to shoot at Dene Park. It would not have occurred to him that there were social pitfalls, even less that his wife and daughter might fear them.

But the day after that terrifying Boxing Day had brought relief. A telegram from Charles was followed rapidly by the man himself, bearing apologies for his absence and an engagement ring for Diana. It was a family heirloom, had been his grandmother’s: a large, round ruby, set about with diamonds, on heavy gold. Now, suddenly, the engagement became real: the ring was there, Charles was there.

Best of all, he said that as it was only fifteen miles from camp to The Elms, and he had a fast motor-car, he would come and visit whenever he had a few hours off-duty – if Mrs Hunter would allow him.

‘Come any time,’ Beattie said. ‘You don’t need to give notice – we’re always glad to see you.’

When Beattie was not worrying about the wedding – with the added complications of the war, and how the Wroughton element was to be meshed with the Hunter – she was thinking about David. It was hard not to feel hurt that he had planned to spend his leave with the family of his friend Oliphant. He had said it was because the Oliphants’ home in Melton Mowbray was closer to camp, so he would not have to waste his leave travelling. Beattie couldn’t help feeling there were other influences at work, which boded her no good.

Highclere Farm, as the name suggested, was at the top of a hill, but still the constant rain had created an ocean of mud.

Sadie did not normally do the rough work, but with eight muddy horses to prepare that morning she insisted on pushing up her sleeves and pitching in. She was excavating the second subject of the morning from its carapace when John Courcy, the veterinary surgeon, appeared at the stable door.

‘My goodness! I didn’t recognise you for the moment. Is it really Miss Hunter under there?’

Sadie straightened, and pushed her hair back with a forearm, adding another streak to her brow. ‘They went and rolled, the wretches!’ she said. ‘They were put out in the top paddock overnight, but there’s a weak place in the hedge, and they broke through and found the lowest, wettest spot in the whole field, and down they went.’ John Courcy was laughing now. ‘They all looked so pleased with themselves when they were fetched in. I swear this one had a smirk on his face.’

‘Which one is it?’

‘Conker,’ she said. The sergeant, Cairns, who had been assigned to them had warned her not to name them in case she got fond of them, but she had done it anyway. Conker was her favourite. She slapped his neck affectionately, and he turned his head and nuzzled her.

‘It might have been wiser to keep them in overnight,’ Courcy said.

Sadie looked stern. ‘I think we know that now,’ she said. She glanced down at herself, then shyly up at him. ‘Do I look very dreadful?’

‘Not at all. Mud becomes you,’ he said solemnly.

He had come to examine the eight horses that were leaving today for the Army Remount Service depot. Two of the original intake of ten had been pronounced not ready by Mrs Cuthbert – after nearly four months of schooling by her, Sadie and the grooms, they were still unreliable, particularly in the face of loud noises. Teaching the youngsters to bear having firecrackers let off near them had been the wildest part of the training process. In the consequent rodeos, Sadie had taken several falls. She’d had to conceal the bruises from her family, for fear she would be forbidden to help any more.

Courcy was looking at her with sympathy. ‘You’re going to miss them,’ he suggested.

She tried to brazen it out. ‘I’m just pleased we’ve got the first batch ready to go.’

‘Of course you are,’ he agreed kindly. ‘Well, I’d better give them a going-over.’ He glanced at Conker. ‘Perhaps I’ll start with the clean ones.’

‘Conker’s the last,’ she said. ‘The others are all ready.’

‘Do you want to leave him for a moment and come with me?’ he asked. ‘You can hold them for me while I look them over.’

She agreed readily, pleased that he had asked. She loved the way he treated her as an equal, not as a child. At home, they would have disapproved of her muddiness; he just laughed. It was only a pity they didn’t see more of him at Highclere. He was attached to the Army Remount Service, so he came whenever they had a veterinary problem, but the Irish horses had been pretty healthy so far. He was also on call for any army units in the area, so she saw him from time to time, buzzing about in his little car. Sometimes he would stop and have a chat with her, but if he was in a hurry he would only wave as he passed.

Now she went with him from box to box, holding the horses while he looked at their ears, eyes, teeth and feet, and listened with his stethoscope to their hearts, lungs and stomachs.

‘You’re very good with them,’ Courcy said. ‘You make my job much easier.’

‘They’re good fellows,’ she said, deflecting the praise. She was not used to being complimented.

One of the grooms had finished Conker when they got to him. He shoved his nose under Sadie’s arm and sighed a great gusty sigh of content as he leaned into her. Courcy thought that, despite her plucky words, she would miss them.

‘Well, they’re fit enough, anyway,’ he said, rolling up his stethoscope. ‘When are they leaving?’

‘The ten past two train. There’s a railway box waiting for them in the siding at Northcote. We’re hacking them down.’

‘You’re going with them?’ Courcy asked.

‘Me, Podrick, Bent and Oxer – ride one and lead one. Mrs Cuthbert will follow in the motor to collect the tack.’

They stepped outside. Just for the moment the rain had stopped, though the sky was grey and threatening. Courcy leaned an elbow on the box door and seemed inclined for conversation. ‘I don’t suppose it’ll be long before you get a new batch in,’ he said. ‘There’s nothing much going on in France at the moment, but they’ll want to get up to full strength before any spring offensive.’

‘Will there be a spring offensive?’ Sadie asked quickly.

‘Oh, I haven’t heard anything,’ he said. ‘It’s just the way armies work. They can’t fight in the current conditions, so both sides will hibernate until spring.’

‘It seems awfully silly,’ Sadie said slowly, ‘to be fighting by rules, like that, when fighting itself is such a … I can’t think of the right word.’

‘Such an anarchic thing?’ he offered.

‘Yes,’ she agreed.

‘I suppose it’s as well there are rules, or it would be even worse than it is,’ he said. ‘You have a brother who’s volunteered, I believe.’

‘David, the eldest.’ She nodded. ‘He’s in training somewhere near Nottingham. He’s longing to get out to France.’

‘Good for him.’

‘He wants to do something noble to serve his country,’ Sadie said with pride.

‘You’re very fond of him,’ Courcy noted.

She nodded. ‘I miss him. Father calls it “leaving the nest” – he says we’ll all hop out sooner or later. I hate the idea of that. I suppose it has to be, but you always hope nice things will stay the same for ever, don’t you? Christmas was strange without him.’

‘You’re lucky to have brothers and sisters,’ Courcy said. ‘There was only ever me at home. The high point of Christmas Day was my father playing a game of chess with me after dinner. Not exactly riot unbounded.’

‘That’s sad for you,’ said Sadie. ‘Brothers and sisters are not always completely lovely but, on the whole, I’m glad to have them.’

‘And your sister is engaged to be married?’ Courcy said.

‘How did you hear that?’

‘Everyone seems to be talking about it,’ he said.

‘I can guess what they’re saying – how amazing that Lord Dene’s chosen a nobody instead of a duke’s daughter.’

‘I’m sure they don’t say that.’

‘I’m sure they do, behind our backs.’

‘Well, not to me, anyway,’ said Courcy. ‘And what do you say?’

‘That he’s in love with her, and that’s all that matters, isn’t it?’

‘To you and me, perhaps. I believe in Lord Dene’s world other things are usually taken into account. What do you think of him?’

‘I’ve only met him a couple of times, but I like him. He talked very sensibly about dogs, and he was nice to Nailer. Nobody’s ever nice to poor Nailer.’

‘Except you,’ said Courcy.

‘And you.’

‘It’s my job,’ he said.

She knew he hadn’t been kind to Nailer only because it was his job. ‘But you like dogs, too,’ she said.

‘I like yours,’ he said.

She met his eyes shyly and had to look away. She had never been shy with grown-ups, but there was something about John Courcy … At the end of a rapid chain of thought that wouldn’t bear inspection, she blurted out, ‘It’s my birthday on the twentieth. I’ll be seventeen.’

He raised an eyebrow. ‘Should one say “congratulations”? I’m not very knowledgeable about such things, but I believe seventeen is something of a milestone.’

‘I don’t know,’ she said. ‘I’m not officially “out” – but I don’t suppose, with the war and everything, there’ll be the old sort of “coming-out” any more. At least until the war’s over.’ She looked up at him. ‘I do think it’s changed things, the war – don’t you?’

‘Yes, but whether the changes are permanent … I suppose it depends rather on how long it goes on.’

At that moment Mrs Cuthbert appeared. ‘Everything all right?’ she called to Courcy as she approached. ‘How did you find my charges?’

‘In tip-top condition,’ Courcy answered. ‘I’ve never seen such a happy bunch of four-year-olds. You must have been tucking them in every night with cocoa and a bedtime story.’

‘Then I take it you’re signing them off. Good-oh. There’s a train for them this afternoon.’

‘So Miss Sadie was telling me.’

Mrs Cuthbert turned her eyes on Sadie and noticed the state of her. ‘My dear girl, you must go indoors and get some of that mud off you at once! I can’t have you riding through the public streets like that.’

Sadie was embarrassed. ‘I don’t see that it matters.’

‘Everyone in Northcote knows you, and it’ll matter if it gets back to your parents and they forbid you to come again. You’re not a child any more.’

‘So I’ve just been told,’ said Courcy. ‘Seventeen is a young lady, Miss Hunter.’

‘“Young ladies” don’t do interesting things,’ she complained. ‘It’s nothing but clothes and dancing.’

‘I’m sorry you don’t like dancing,’ said Courcy. ‘I imagine you’d do it rather nicely.’

She thought about dancing with him, and was confused. ‘Of course I like it. But it can’t be all dancing. There has to be something else to life as well.’

Courcy was sorry to have teased her. ‘I agree. Dancing is far from everything. But it’s pleasant while it lasts.’ He turned to Mrs Cuthbert. ‘I’d better complete the documents for this lot.’

‘Yes, of course,’ said Mrs Cuthbert, and added to Sadie, ‘Go up to the house and have a wash, and ask Annie to brush your clothes and clean your boots. I’ll be up in a minute and look you out one of my clean shirts.’

Sadie escaped gratefully, but still couldn’t help looking back when she reached the gate for a last sight of John Courcy. But he had turned away with Mrs Cuthbert and she only saw his back view.

She felt proud bringing up the rear of the cavalcade, leading Ginger and riding Conker for the last time. The horses were enjoying being out as a group and were trotting nicely, carrying their heads well and keeping pace with each other as if they were on parade. How different they were from the wild bunch delivered back in September! She was particularly proud when a motor-car idling at the kerb backfired explosively just as they passed, and none of the horses missed a beat.

As they rode through the streets of Northcote, people turned to look, and those who knew her called out and waved to her. There were quite a few soldiers about. After five months, it no longer surprised her, though she always noticed them. The Tommies gave a cheer when they saw she was a girl, and she smiled in response.

There were other reminders of the war, too: red-white-and-blue bunting round the window of Stein’s, the butcher’s; portraits of the King and Queen in Hadleigh’s window; the words ‘BUSINESS AS USUAL’ on the side of a Simpson’s Dairy cart going by. On the railings by the police station there was a recruitment poster, and the advertisement for the Electric Palace in Westleigh had a new sticker across it saying ‘Service Men (in uniform) Free’. And as they reached the station yard, the Charrington’s coal dray pulled out, drawn by a pair of mules, instead of the lovely shires that had been commandeered by the army. Yes, she thought, clattering into the yard, though most things seemed much the same as always, you wouldn’t have any difficulty in remembering there was a war on.

She helped untack and box the horses. They were offered water, but they wouldn’t drink – there was a little hay in the rack along one side and they were more interested in that. It was time to say goodbye and, despite her good intentions, Sadie felt tearful. She left Conker till last; but when she caressed him he gave her only a perfunctory nudge and continued tugging eagerly at the wisps of hay.

Podrick, the head man, was waiting at the foot of the ramp. He gave her a sympathetic look. ‘They’ll be all right,’ he said.

‘I know,’ she said, swallowing the lump in her throat. Podrick, Bent and Oxer were standing by the heap of tack, waiting for Mrs Cuthbert to arrive and take them back. She felt a sudden desire to be alone, and said, ‘There won’t be anything for me to do at Highclere this afternoon. I think I’ll go home.’

‘Missus’ll give you a lift,’ Podrick said.

‘Oh, no, thanks. I’ll walk. Will you tell her for me?’ And with a nod to the grooms, she set off.

It started to drizzle when she was halfway home, and a glance at the sky told her proper rain would be setting in soon. She hunched into her collar, put her hands into her pockets and increased her pace. As she turned in at the gate of The Elms she spotted Nailer sheltering under the laurels. He stuck out his whiskery white muzzle when he saw her, and when she stopped and spoke to him he came out.

‘You’re soaking!’ she said, and he swept his tail back and forth in apologetic agreement. It was getting colder, too, and she could see him shivering. ‘Come on,’ she said.

She managed to sneak him in by the scullery door, and used the towel from the sink there to dry him. He went limp in her hands, his eyes closed in bliss and his jowls flopping as she rubbed him vigorously to warm him up. ‘You’re such a fool,’ she told him. ‘Why didn’t you shelter?’

Too much to do, he said in her head, in the growly voice and Hertfordshire accent she always imagined for him. Places to visit, things to sniff. Don’t forget the ears, my girl.

‘I’m not your girl. I’m about the only friend you’ve got, however. Except for Mr Courcy.’

Those are the only ears I’ve got, so not so rough, my maiden, if you please.

‘How’s that?’

Better. So you’ve been talking with Mr Courcy, have you? I hope you’re not getting spoony on him.

She stopped abruptly, having managed to confound herself. ‘What a ridiculous suggestion,’ she said aloud.

David sat at the dinner table at the house of his friend Oliphant with the rumble of conversation rolling gently over his head. Mrs Oliphant had invited guests: the neighbours from next door, Colonel and Mrs Fentiman, and their daughter Penelope. David was seated next to her, and on Mrs Oliphant’s left. Dinner at the Oliphants’, when there were guests, was always rather formal, and Mrs Oliphant did not approve of talking across the table, which meant that David had to divide his attention between Miss Fentiman and his hostess. Miss Fentiman was slightly gingery, with a plump chin and sandy eyelashes, and whether she was dull or merely shy he didn’t know, but it had been hard work to prise anything out of her except yes and no.

He had managed to get over his guilt about not going home. His excuse, that the Oliphant house was closer, was true, but he knew his mother would be upset even so, and he didn’t like to upset her. He had missed them all at Christmas, but he belonged to the army now, and Mother had to realise he was a man and made his own decisions. Anyway, the slight discomfort at the back of his mind where his conscience lived was no match for the pleasure of being in the same room as Oliphant’s sister, Sophy.

At last the sweet plates were removed and the dessert put on, which meant that general conversation could take place. David abandoned the unrewarding Miss Fentiman and lapsed into silence so he could gaze across the table at Sophy. He thought her the most beautiful girl in the world, and her beauty was only enhanced by comparison with the neighbours’ daughter.

Sophy was small, delicately made, with dark hair and dark eyes that seemed large in her pale face. Her neck was long and slender and swan-white. He adored her neck. There were one or two tiny curls at the nape, escapees from the confines of her chignon, and he found them utterly distracting. A few weeks ago, some of the men at camp had passed round illicit photographs of women in their underwear, some with their breasts almost uncovered. David had been unmoved by them, but those little curls, with their suggestion of déshabille, could make him go hot and cold in quick succession.

Now and then her eyes would meet his across the table, to be quickly averted, accompanied by a faint blush. It was all the encouragement he needed to keep looking at her, until he accidentally caught Oliphant’s eye instead, and his friend gave him a smirk of amusement and a pitying shake of the head, after which he pulled himself together and listened again to the conversation.

‘The newspapers are full of nonsense these days,’ Oliphant père was saying. ‘No proper war news at all. I suppose that’s the government’s doing, eh, Fentiman? Censorship for our own good?’

‘What the people don’t know can’t hurt ’em,’ said Fentiman. ‘Better to keep up morale.’

‘Hence all these heartwarming stories, I suppose,’ said Mrs Fentiman, ‘about missing sons turning up, and acts of heroism at the front.’

‘I like to read of such things,’ Mrs Oliphant pronounced. ‘There was an account in the newspaper about a soldier who went into a barn to fetch straw and found two armed German soldiers hiding there. He had no weapon with him but a pair of wire-cutters, but most bravely and resourcefully, he pointed them at the Germans and shouted, “Hands up!” The Germans threw down their rifles and surrendered.’

‘Oh, Mother, that’s an old chestnut,’ Oliphant junior objected. ‘It’s been around so long it’s got whiskers on it.’

‘I don’t like that sort of talk, Frederick,’ Mrs Oliphant said sternly. She was a large, solid, well-corseted lady, with iron-grey hair tightly waved in old-fashioned parallel crinkles. Her spectacles magnified her pale eyes to alarming size, and she bent them reprovingly on her son. ‘I’m quite sure the story is true, or it would not have been published in the newspaper.’

Mrs Fentiman stepped in, accustomed to her neighbour’s literal cast of mind: ‘At any rate, it illustrates how plucky and quick-witted our fellows are. A Tommy is worth two Fritzes.’

‘Quite right,’ Mr Oliphant said. ‘We can all agree about that, at least. But, Fentiman, you have a better source of information than any of us. What’s the plan for rolling up the Germans this year?’

‘It’s a tricky situation,’ said Colonel Fentiman. ‘My friend at Horse Guards says the War Council’s been considering pulling out of France altogether.’

‘Surely not!’ said Mr Oliphant.

Fentiman nodded. ‘The front stretches from the Swiss border to the Channel without a break, and the enemy everywhere is on higher ground. There’s no German flank to be turned, and we’ve already seen that frontal attack is bloody and futile. Those casualty lists in the autumn have rattled the government. It’s not at all clear what can or should be done.’

‘But, sir,’ said young Oliphant, ‘the New Army will be ready this year. I know we were heavily outnumbered last autumn, but once we Kitchener chaps are ready, surely they’ll send us to France to knock Jerry for six? Or what are we training for?’

David wondered the same thing, and looked at Colonel Fentiman with painful urgency. From the beginning they had all been afraid the war would be over before they got out there.

The colonel recognised their eagerness: if he had been their age, he’d have felt the same.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...