- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

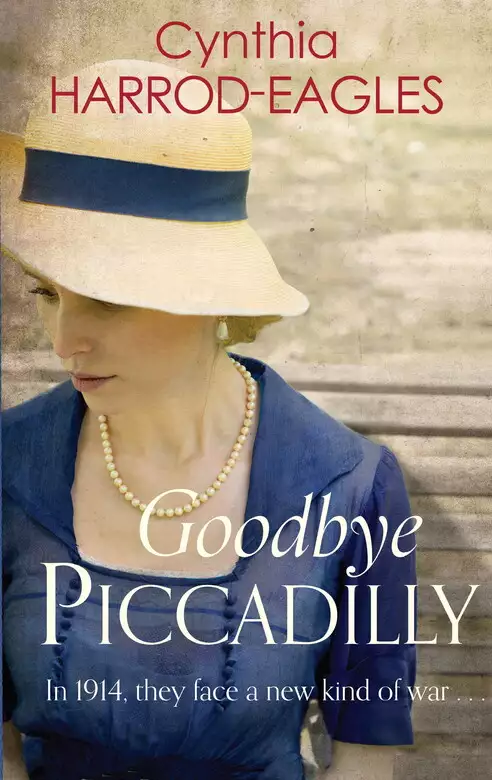

Synopsis

In 1914, Britain faces a new kind of war. For Edward and Beatrice Hunter, their children, servants and neighbours, life will never be the same again. Perfect for fans of Downton Abbey and Barbara Taylor-Bradford. For David, the eldest, war means a chance to do something noble; but enlisting will break his mother's heart. His sister Diana, nineteen and beautiful, longs for marriage. She has her heart set on Charles Wroughton, son of Earl Wroughton, but Charles will never be allowed to marry a banker's daughter. Below stairs, Cook and Ada, the head housemaid, grow more terrified of German invasion with every newspaper atrocity story. Ethel, under housemaid, can't help herself when it comes to men and now soldiers add to the temptation; yet there's more to this flighty girl than meets the eye. The once-tranquil village of Northcote reels under an influx of khaki volunteers, wounded soldiers and Belgian refugees. The war is becoming more dangerous and everyone must find a way to adapt to this rapidly changing world. Goodbye Piccadilly is the first book in the War at Home series by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles, author of the much-loved Morland Dynasty novels. Set against the real events of 1914, Goodbye Piccadilly is extraordinary in scope and imagination and is a compelling introduction to the Hunter family.

Release date: June 19, 2014

Publisher: Sphere

Print pages: 401

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Goodbye Piccadilly

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

Sadie loved riding, but keeping horses was not within her father’s means, so she had to take rides where she could get them. Arthur was one of Simpson’s Dairy’s horses, and she had offered to ride him down to the forge to have a loose shoe seen to. He was large and white and bony, with a pendulous lip and a docked tail, and he had only one plodding pace. But he gazed round and pricked his ears now and then, and she believed he was enjoying the break from routine – until a stone shot out of the hedge and hit him on the stifle.

He jumped, and snorted in protest. Sadie soothed his neck, and looked round. ‘Come out, you boys!’ she said sharply; and then, ‘I see you, Victor Sowden! Come out this minute!’

A group of boys pushed through the gap in the hedge: boys unkempt of hair and grubby of face, in hand-me-down suits and sagging stockings. They were all around eleven, except for the ringleader, Victor Sowden. He was big for his age, which was thirteen: a knuckly, raw-faced boy, the only one in long trousers. Wherever there was trouble, it was a fair bet that Victor Sowden would be at the bottom of it.

He lived in a tumbledown cottage on Back Lane with a large family of siblings. His father was – intermittently – a farm labourer, a frequenter of the Red Lion and not unknown to the police, and his mother was a hopeless slattern, worn down by childbearing and her husband’s fists.

Victor cared for nobody but, unusually, he loved animals. Sadie had a reluctant half-liking for him, ever since he had fought a bigger boy who was stoning a cat. And perhaps it was because of Arthur that, instead of running away, he remained there, glaring at her sulkily.

‘How dare you throw a stone at my horse?’ she said. ‘You should know better.’

‘Never frew it at you,’ he said. ‘Frew it at them.’ He jerked his head towards the other boys, ready to run but lingering on the edge of the scene, gripped by the eternal boyhood longing to see someone else ‘catch it’.

‘Why?’ Sadie was moved to ask.

He shrugged his bony shoulders. ‘Chuckin’ a grenade. Never meant it to ’it yer ’orse,’ he added.

The largest of the other lads, Olly Parry, from Parry’s Farm, spoke up. ‘We’re sojers. Germans an’ English.’

The smallest boy, whom she recognised under a fine mask of dirt as Victor’s brother Horry, complained shrilly, ‘He always makes us be the Germans.’

Sadie addressed Victor: ‘Shouldn’t you be at work?’ He shrugged again, and she surmised that he had been ‘let go’ from his latest employment. He ought to be put into a job with horses, she thought, but with his reputation, few people were willing to employ him. She felt oddly sorry for him, so she just said, ‘Don’t throw stones. It’s dangerous,’ and rode on.

Germans and English! she thought. Ten years ago, at school in Kensington, she had sat next to a German girl, Bertha, who used to jab her in the ribs with her ruler and whisper, ‘Our king’s going to come over and fight your king, and our king’s going to win.’

Sadie, of course, had had to return the jab and whisper, ‘No, our king’s going to win.’

So the exchange would go on until Miss Madison glared them to stillness. All those years later, and it was still Germans and English!

Arthur turned off the road on to the track that led to Simpson’s stables without her help. The stableman, Gallon, came out, took the rein, and asked, ‘How did he go, then?’ rather in the manner of a head groom enquiring after a prize hunter’s performance to hounds.

‘Very well,’ Sadie said obligingly. ‘And he stood like an angel in the forge.’

Gallon stroked the white neck with quiet pride. ‘Ar, ’e’s a good old ’orse, is Arthur. Shows these young ’orses a thing or two.’

She agreed, indulged him in a brief chat in payment for her ride, then set off on foot for home – The Elms, in Highwood Road.

Diana was on the sofa in the morning room, flicking through the magazines. Aunt Sonia Palfrey in Kensington sent them to her when she had finished with them. The Illustrated London News and Ladies’ Home Journal came regularly, sometimes Vogue and Tatler too, given to Aunt Sonia by a wealthy American neighbour.

The fashion in Paris this season, apparently, was for unrelieved black. She wondered how that would go down. Black suited her, fair as she was, but wouldn’t people think you were in mourning? Not that it mattered here, in Northcote: though it was only twenty miles from London, it was hardly a hub of fashion. People who moved here seemed to forget the capital existed, let alone any world further off.

But this evening, at least, the wider world was coming to them. Cousin Jack and his wife Beth were to visit, and Jack was giving a magic-lantern lecture in the village hall on their recent walking tour in Switzerland.

He was only a year or two younger than Father, the son of Father’s much older half-brother, George. Uncle George had died years ago. Diana remembered visits to his large, dark house in Hampstead. A tall and portly figure with a gold watch-chain straining across the widest part of his middle, he used to let her light his cigars for him: she loved the first smell when the tobacco caught. And there was a drink he had given them one Christmas, dark red and tasting hotly of cinnamon. It had seemed at the time the essence of Yuletide. Diana had taken the fancy that Uncle George, with his full beard and moustache, was really, secretly, Father Christmas.

There had been no Aunt Agatha on the scene – she had died before Diana was born; and Cousin Jack had already been out in the world. He had always seemed exciting to the children, a meteor that streaked across their everyday firmament. He had been a soldier, and served in exotic places; and when he left the army, having inherited Uncle George’s fortune, he had indulged his great passion for travel. Luckily he had married a woman who shared his tastes. They had always brought fascinating souvenirs from China or Mongolia, Mexico or Afghanistan. Sadie still had her doll from Japan.

Switzerland seemed a mite less exotic than their usual destinations – she imagined it full of mountains and cuckoo-clocks – but it was still a far cry from Northcote. And everyone loved a magic-lantern show: the village hall would be packed. Best of all, he and Beth would be staying overnight, and there was to be a supper at home after the lecture, to which all the important people of Northcote were invited.

The question was, would the Wroughtons come?

The Wroughtons of Dene Park were the most important family in the area by a long margin, barons from the seventeenth century and elevated to the earldom in 1910 by Lloyd George. Dene Park, their country seat, was a Palladian mansion in extensive parkland, whose gates were only half a mile from The Elms. It was another mile from the gates to the house itself, a fact recorded with pride in the local guidebook. Still, by any measure they were neighbours.

And in addition, Father was acquainted with the earl: Edward Hunter was a senior manager of Hutcheon’s Bank, and the Wroughtons had always banked with Hutcheon’s. The Wroughtons did not spend a great deal of time at Dene Park, and so far the contact had all been between the earl and Father – and not very much of that. There had been one or two notes passed between them, the odd present of game or hothouse fruit, and invitations for the occasional day’s shooting.

But there was no reason why that should not change. Even Mother, moving serenely, it seemed to Diana, in another world, had seen the possibility offered by Jack’s visit. The Wroughtons had been invited to the lecture and the supper afterwards. But would they come?

Or rather – since Diana’s interest in the Earl and Countess Wroughton was limited – would he come? Their son, Charles, the Viscount Dene, to give him his title: the eldest son – the heir. He had been just a vague figure on the distant horizon until she’d had the good fortune to meet him, twice, in London, when she had been staying with the Palfreys in Kensington. Oh, thank God for the cousins! Always willing to have her to stay, which gave her access to proper shops, theatres, dances, and always an excuse, when Northcote grew too cramped, to catch the train up to London for a breath of less-than-fresh air.

She had first met Charles Wroughton last December, in Belgravia, at a party of some connection of the cousins, where the crush was dreadful and you could hardly hear yourself speak. He had been introduced to her and she had managed to mention that they were neighbours in the country, but she wasn’t sure he’d taken it in through the din. He’d given her no more than a polite nod and an apologetic look when he was dragged away by the hostess.

Mary, the Palfrey cousin closest to her in age, had told her he was famously stiff and stand-offish, and she had not expected the encounter to lead anywhere. But he had been present at a hospital ball at Grosvenor House in May, and when she caught his eye across the room, she had seen a look of puzzled recognition, to which she had replied with the sort of smile that said, ‘Yes, we are acquainted, it’s quite safe to come over.’

And he had come. Explanations were given, acknowledgements exchanged; he had asked her to dance! It was a moment of triumph. She had seen looks following her as he led her on to the floor: Viscount Dene, so aloof and difficult to get to know, and Diana Hunter, merely a banker’s daughter. She had known she was at her best that evening, she had been out for two years and an acknowledged beauty for two before that, but still she was nervous. She had to find some way to make an impression on him. Asking her to dance had been a big first step for him, but he did not seem to be much of a talker, and it was hard to be charming with so little to work on. Yet she felt he had noticed her. He didn’t smile, but there was something in the way he looked at her …

He had danced with her twice, but he was there with a party and had been obliged to rejoin them, and since then she had not happened to meet him. Two dances two months ago was so little to hold her in his memory. He must dance with so many girls. She could almost feel herself fading from his mind, like a ghost at cockcrow. She had to see him again soon, to have any chance.

‘Why should you care?’ Sadie had said, when Diana wondered if he would remember her.

‘Oh, you don’t understand,’ Diana had replied.

Ordinary-looking girls always envied Diana. They said, ‘Oh, you are lucky,’ and ‘It’s all right for you,’ and imagined her life to be easier than theirs. But with great beauty came great responsibility: she had to marry well. It was expected of her. Sadie could wait, and marry anyone she liked, as long as he was respectable. But for Diana, waiting was an unaffordable luxury. Beauty, like a rose, had its season. Year by year it diminished, and day by day it was threatened. Sometimes she woke in the night in a panic. And when she stared in the looking-glass, it was not vanity but anxiety.

Since she had come out, plenty of local boys had chased after her. But even those she liked, she did not encourage. She had to marry well, and Charles Wroughton was her best chance. If only he came tonight … She knew he was at Dene Park, because their charwoman, Mrs Chaplin, was aunt to the blacksmith, Jack Chaplin, who had done a small repair on Lord Dene’s motor-car, which he liked to drive himself. He had taken it to the forge in person and, standing chatting to Chaplin while the repair was done, had mentioned that he was down at Dene Park for the whole summer.

The Wroughtons had not replied to the invitation, but that meant nothing. They might still come. If only he accepted the invitation … Especially the supper … She could manoeuvre him to a quiet corner of the room where they could talk. If only he came …

Sadie’s route home led her past All Hallows Church and the rectory. The rector’s wife, Mrs Fitzgerald, was in the garden cutting roses. She beckoned to Sadie as she went past, coming over to the gate to meet her. Sadie obeyed with sinking heart. Mrs Fitzgerald, whom one was obliged to admire for her energetic philanthropy – she was an example to them all, not least according to herself – always meant trouble.

‘How is your dear mother?’ she enquired. ‘Busy getting ready for this evening, I imagine?’

Sadie gave a noncommittal sort of ‘Mmm.’

‘You will please tell her,’ Mrs Fitzgerald went on, ‘that if she needs any help, I will send my Aggie over to led a hand.’

‘I’ll tell her,’ Sadie said, knowing full well that the famously sharp-tempered rectory maid would cause more trouble than she was worth, and that her mother’s servants would resent the notion they couldn’t manage. ‘Thank you. But I’m sure she’s all right.’

She had a fair idea that the offer was made less in the spirit of generosity than from a desire to meddle. Mrs Fitzgerald couldn’t bear anything in Northcote to happen without her, and used her position as rector’s wife to ensure it didn’t. Sadie had the middle child’s quickness at summing people up, and she absorbed things when people thought she wasn’t listening. She knew that Mrs Fitzgerald felt that the magic-lantern lecture should have taken place in the church hall rather than the village hall. That would have put her in charge of all the arrangements, and allowed her and the rector to hold the supper party afterwards. It was more fitting, since they could fairly be held to represent the village: Mrs Hunter was taking advantage of the completely irrelevant fact that the lecturer was Mr Hunter’s nephew.

It would be interesting to hear all this from Mrs Fitzgerald herself, but Sadie knew, without actually thinking it out, that egging someone on to expose themselves was not a sport for someone low down in the social order, like her. Wounded top dogs were likely to bite. Instead, to deflect the rector’s wife, she asked, ‘How is Dr Fitzgerald’s throat?’

‘Much better, thank you. Dr Harding said there wasn’t any infection. It was just a strain. He advised Rector only to talk in a whisper for a few days, and says he will be back to normal by Sunday.’ Mrs Fitzgerald, not wholly deflected, was examining Sadie even as she spoke. ‘I expect you’re going home now to help your mother, aren’t you? It must be nice for her to have you at home on an occasion like this. But, my dear, what are you going to do with yourself? Idling about the countryside like this…’

‘It’s the summer holidays,’ Sadie said.

‘You know I don’t mean that, child. You’re how old? Sixteen, isn’t it? So school is finished for you now. It won’t do to get into idle habits. I assure you, men want active, useful wives. Does your father mean to send you to a finishing school?’

‘I don’t know,’ Sadie said, trying to edge away. There had been talk of a finishing school in Vienna, the same one Diana had gone to, but nothing had been said recently.

‘Well, dear, you must do something. There’s your sister at home already,’ the rector’s wife pursued. ‘Not that Diana will have any difficulty finding a husband, so truly beautiful as she is. But you – well,’ she concluded, having given Sadie another up-and-downer, as her brother William called such looks, ‘you will have to work that bit harder, as I’m sure your mother knows. It must worry her to have you thumping about the countryside like a hoyden. You should take up some ladylike pastime – the piano, or flower-arranging, for instance.’

Sadie had fidgeted herself as far away as she could without actually leaving, so she broke in now in desperation and said, ‘I’m so sorry, Mrs Fitzgerald, but I have to go. Mother’s waiting for me.’

‘Oh, quite, quite. Well, give her my regards, and don’t forget to tell her I’ll send Aggie over if she needs her.’

‘I won’t,’ Sadie said, pleased with the ambiguity of the answer, and made her escape. She hurried until she was round the corner and out of sight, then slowed, and mouthed a silent ‘Phew!’ at the sky. She supposed she was going to get a lot of that sort of thing from now on. A finishing school – which might or might not be fun – would only be postponing the inevitable. What, after all, could a girl of her class do except get married? You couldn’t have a career, like a boy. If a girl didn’t marry, the prospect was grim. She ‘stayed home and helped Mother’, and eventually looked after her parents in their old age.

Well, nothing would happen until September, anyway. She had the last bit of July, and all of August … It was a shame the older boys weren’t at home to make fun for them. They had gone, David straight from university and Bobby straight from school, to stay with friends for the summer. That left only Diana, who was too old to be of any use to her, and Peter, seven, who was too young. William, who was fourteen, had lately developed an obsession with engines, especially aeroplanes, and went off with other boys of similar bent to ‘spot’ them in whatever places these things could be spotted.

There was the annual trip to Bournemouth in August to look forward to, but she had an idea that Diana might get out of it this year, which would leave her with just William and Peter and the faint suspicion that she was getting too old for seaside holidays, rock pools, sandcastles and donkey rides. Was it possible, she wondered, rustling her hand through the long grass of the verge as she ambled along, that sixteen was the worst age of all to be? Too old to play and too young to be grown-up …

At the corner of Highwood Road she met their dog, Nailer, turning in from the other direction. They halted and looked at each other. Nailer was a white, terrier-type mongrel, a squareish, bustling kind of dog, with a coarse coat, cocked ears, bushy eyebrows and stiff white moustaches that hinted at a drop of Scottie in the general mix. He somehow managed to combine contempt for his humans with ingratiation, so that he always ended up being forgiven for the shortcomings in his character, which were many. He loved digging, fighting, stealing food, chasing cats and killing rats. Pursuit of his pleasures led him widely over the countryside, and his carnal reputation was high – or low, depending on your point of view. There were few farms or hamlets within a range of, say, five miles where an apologetic bitch had not at some point given birth to a litter of squirmers sporting those distinctive whiskers, the badge of her shame.

Nailer looked at Sadie cautiously from under his frosty overhang, keeping a judicious distance, stiff tail wagging, until he determined his welcome. A dog with a clear conscience might have come forward with open friendliness, especially to Sadie, but Nailer knew that, for some mysterious reason, almost everything he did was frowned on by the two-leggers.

Sadie smiled. ‘Good dog,’ she said. ‘Where have you been, then?’

Relieved, he came up to greet her, discovered traces of Arthur and gave her a full and frank going-over.

‘You and I are the only ones who like the smell of horse,’ she said. ‘Diana will turn up her nose at me until I change.’ She sighed. ‘I hope I don’t get as silly as her when I’m her age. Come on, let’s go home. I’m starving.’

Nailer bared his teeth in what passed with him for a smile, and fell in beside her.

There was a fine big copper beech in the garden of the Oliphants’ country house. David Hunter was lying on the grass in its dappled shade; his friend Oliphant was sitting with his back against the trunk, smoking a gasper and watching the fumes drifting gently up into the leaves. They had been taking turns in reading Ovid aloud, and talking, as men at university throughout the ages always had, about Life, and love, and women. Their experience of all three was necessarily limited to the intellectual rather than the practical, and some time ago they had lapsed into silence.

At last David said, ‘Don’t you think this life of ours is sterile? Reading books, theorising, the whole academic world … Look at our dons: shut away in cloisters. None of them knows what’s really going on outside. We ought to be living life, not endlessly discussing it.’

Oliphant considered. ‘But isn’t some kind of preparation for life necessary? An apprenticeship of thought?’

‘Good phrase,’ David said.

Oliphant tried not to smirk. He didn’t often get compliments. ‘After all,’ he went on, ‘ignorance means you don’t know how ignorant you are. Until we know, we can’t tell what we need to know.’

‘Oh, more words! I’m tired of living through words. I want to do something.’

‘What sort of thing?’ Oliphant asked reasonably.

‘I don’t know!’ David cried in frustration. He sat up. ‘I want the chance to do something glorious and noble. There must be honour somewhere in the world. We’ve become decadent in this country. We need to shake off the shackles of ease.’

‘Good phrase,’ Oliphant offered him back.

‘Civilisation is smothering us! You see it everywhere – the base, ignoble concerns of earthbound creatures.’

‘But doesn’t one have to earn a living somehow?’ Oliphant said doubtfully.

‘I suppose so,’ David said restlessly, ‘but must it be the whole of existence? We need to get back to a simpler, cleaner state of being. Like the noble savage…’

‘I say,’ Oliphant protested.

David took a breath, and let it out. ‘Was I getting carried away?’

‘No, it’s good. You make me think. Much more than old Ovid does, anyway.’

‘So much for Life,’ David said lightly. His saving grace was that taking himself seriously was an intermittent fault. ‘Now, about Love.’

‘I’m not sure I shall ever fall in love,’ Oliphant said. ‘Women are too mysterious. Dark and dangerous.’ Down by the house he saw his mother and his sister Sophy arriving back from their afternoon of visiting. ‘Except one’s family, of course, but they don’t count. And even they can be very peculiar.’

David looked and saw them, too. The sight of Sophy’s slender form, seeming to float in white summer muslin, illuminated briefly by the sun as she passed in through the french windows, caused a tremor somewhere inside him. It was only on this visit, the most recent of many to the Oliphants’ home, that Sophy had seemed to step out from the background into sharp relief.

‘I sometimes wonder if they are so very different from us,’ he said, more in hope than conviction. ‘If you could get a girl away from everything and talk, really talk to her—’

‘But you can’t, that’s the whole thing,’ said Oliphant.

‘Don’t you believe in love?’

‘I don’t think it’s a matter of believing,’ Oliphant said gloomily. ‘I think it’s just something that happens to you, like tumbling down a mineshaft.’ David shook his head disapprovingly. ‘You’re too romantic,’ Oliphant went on. ‘It’s not the Crusades. It’s dances. Tea parties. Mixed doubles.’

David drew up his knees and wrapped his arms round them. ‘I don’t care,’ he said. ‘I firmly believe my life is on the cusp of something tremendous. I don’t know what it will be, but I’m ready for it.’

‘You’ve another year at Oxford, don’t forget,’ said Oliphant. ‘I wouldn’t recommend falling in love before you’ve settled into a career. You may despise money-grubbing, but women come expensive.’

‘Dark, dangerous and expensive. Your women sound most uninviting.’

‘If you’d met my cousin Hetty…’ said Oliphant. ‘I wish you were coming with us to Scotland. I’m sure she has designs on me. You might act as a buffer state.’

‘Thanks, but I’ve no wish to throw myself into the path of a rampaging cousin.’

‘Well, you wanted adventure. And there are other females as well.’

Sophy, for one, David thought.

‘Come for the shooting, anyway,’ Oliphant pressed.

‘I’d like to, but I’ll have to ask my parents. Will yours mind?’

‘Of course not,’ said Oliphant. ‘The more the merrier, Ma always says. I think she feels about Aunt Cratty the way I feel about Cousin Hetty – buffer states always welcome.’

‘You paint a most inviting picture,’ David said. ‘Toss me a ciggie, won’t you?’

‘Servants’ hall’ was a generous term for their sitting-cum-dining-room off the kitchen, but it was good sized and comfortable, with a long table covered in a brown chenille cloth, several armchairs clustered round the fire, and various ornaments and knick-knacks giving it a home-like feel. Some belonged to individual servants, but others, like the mantelpiece clock, the Japanese fire screen and the framed prints on the walls, had been donated by the family, objects they had no more use for.

The servants at The Elms had their elevenses at half past ten, but in accordance with local practice they called it ‘lunch’ (their main meal at midday being ‘dinner’). All except the gardener, Munt, that was, who called it ‘beaver’. His first job had been as under-gardener to a retired don. One day during his first week the boy Munt had been toiling in the borders in the hot sun when his extravagantly bearded employer came upon him and said, in the rich and fruity tones that the little Munt had thought would suit God Himself: ‘Good heavens, boy, don’t you know the others have gone for their beaver? Scurry along now. The labourer is worthy of his hire, you know.’

Thus had been born a lifelong hero-worship, though as the professor had even then been in his eighties, little Munt had had only two years to incubate it before the old fellow died and he’d had to move on to another place. But still he was wont to say, ‘Ar, he was a real gentleman, was Professor Scrimgeour. He wouldn’t have had no truck with this ’ere,’ whenever some slackness of modern manners provoked him, which was often. The rest of the staff had heard as much about Professor Scrimgeour as they ever wanted to, and generally told Munt to ‘shut up about the old geezer’, thus neatly proving Munt’s point.

Just before half past ten Emily, the kitchen-maid, had spread the cloth and was vaguely smoothing out the creases when Ethel, the under-housemaid, came in and gave her a sour look. Emily was a skinny little Irish thing and widely agreed to be half witted – though a kitchen-maid’s life was such hell that generally only a half-witted girl would stick it out.

Emily knew what they thought of her, and both did and didn’t care. She thought it was mean, but life had never taught her to expect any better treatment. And she wasn’t half witted, though she couldn’t read or write: her apparent vagueness came from her habit of retreating from the harshness of real life into a world of richly stocked imagination, where characters from the stories of her rural Irish childhood frolicked. Here, where the real Emily lived, were fairies and demons, talking animals, hidden gold, tricky elves and wicked witches, magic transformations, and sometimes – best of all – happy endings.

Ethel saw only ‘that girl’ bending across the table and smoothing the same place over and over like a faulty automaton. ‘Haven’t you laid the table yet?’ she demanded. ‘There’s no time for your nonsense today, with all there is to do, big party tonight an’ all. I’m not getting left with your work as well as my own because you’ve gone potty again.’

Emily turned to face her. ‘I’ve not gone potty,’ she protested, in her soft Donegal lilt. ‘’Twas tonight I was thinking about. Magic-lantern show! Oh, Ethel, won’t it be lovely? I’ve never seen one before. I can hardly wait.’

‘It’s not real magic, you know,’ Ethel said impatiently. ‘I s’pose you think electric light is magic, too. And motor-cars.’

‘I’m not daft,’ Emily said reproachfully. ‘Even if it’s not magic, it’s something new. Can’t a girl be excited?’

‘You can’t be excited about nothing till you’ve laid that table. Come on, bustle about! The others’ll be here in a minute.’ She gave Emily a shove in the direction of the cutlery drawer and, by way of priming the pump, grabbed a stack of plates from the dresser and began putting them out.

Emily got only halfway to the drawer. ‘At the show tonight, Ethel – can I sit next to you? Ah, go on! I don’t want to sit next to Cook. She’ll keep telling me off and I won’t hear what the man says. Please, Ethel!’

Ethel stopped laying plates and gave her a tight, smug look, like a cat. ‘You can sit where you like. I shan’t be there.’

Emily was shocked. ‘But the missus has given us the time off for it, and it’s awful kind of her. You have to go.’

‘I can do what I like with my own time off,’ Ethel said, and pushed at the hair under her cap in a preening sort of movement. ‘I’ll be back in time to help at supper, but I’ve got be

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...