- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

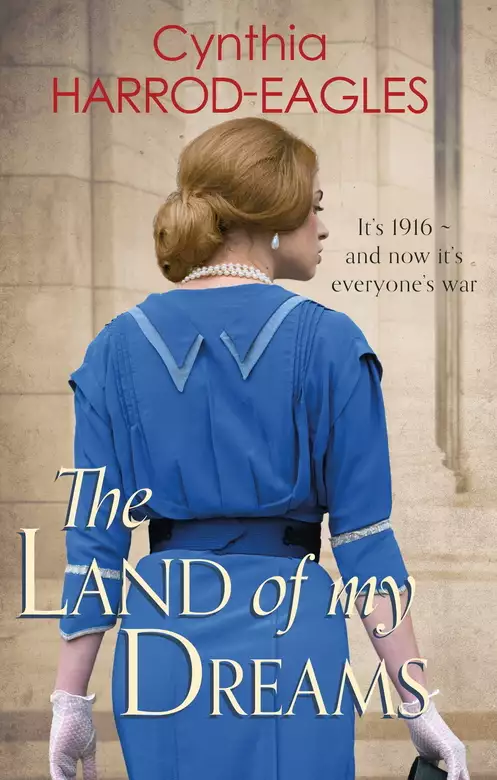

Synopsis

It is 1916 and the Hunters, their friends and their servants are settling down to the business of war.

As conscription reaches into every household, Britain turns out men and shells in industrial numbers from army camps and munitions factories up and down the land. Bobby, the second Hunter son, gains his wings and joins his brother in France. Ethel, the under housemaid, embarks on a quest and Laura Hunter sets out on her biggest adventure yet. Diana, the eldest Hunter daughter, finds a second chance at happiness in the last place she'd think of looking, and matriarch Beattie's past comes back to haunt her.

But as the battle of the Somme grinds into action, the shadow of death falls over every part of the country, and the Hunter household cannot remain untouched.

The Land of my Dreams is the third book in the War at Home series by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles, author of the much-loved Morland Dynasty novels. Set against the real events of 1916, at home and on the front, this is a richly researched and a wonderfully authentic family drama featuring the Hunter family and their servants.

Release date: June 16, 2016

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Land of My Dreams

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

There was something different about David. All her other admirers liked the same things that she did: tennis, dancing, gramophone records, parties. They spoke the same language. David was almost like a figure from history: a Cavalier, a Crusader. He was so tall, heroic-looking; he read books, he quoted poetry, sometimes in Latin; he was serious and thoughtful. And he had volunteered right at the beginning of the war, which was splendid. So when he had begged her, so earnestly, to marry him, she had felt honoured.

She half thought her father would put his foot down – it was no secret he wanted her to marry Humphrey Hobart, the son of a neighbouring landowner. Humphrey was nice, but he wasn’t exciting, like David. But Papa had given his blessing, and David had given her a pretty ring of turquoises he had brought back from France, in a box stamped with the name of a Parisian jeweller. Her friends had been very impressed with the box!

And now here she was, walking from the station to his house to meet his family. It had begun to rain, and she was afraid she was getting splashes on her suede boots. She felt he ought to have got them a taxi, but he was holding the umbrella entirely over her, to the detriment of his own uniform. He did look so fine in uniform, she thought, with satisfaction.

A girl had only one chance to make a good marriage and secure her future comfort. She knew very little about David’s prospects, though she supposed Daddy must have asked about them. She knew his father was ‘a banker’. Vaguely she thought about the funny little man behind the counter at the London and Provincial in Melton Mowbray, who wore a wing collar and gold pince-nez, and combed his hair over the top of his bald head. David had said he would go into banking after the war, and that it was a good career. Daddy must think so, or he would never have agreed. The Hunters were well-to-do. It must be a different sort of banking.

They had stopped at last before a house. It was handsome and large, and the door was opened before they reached it by a respectable-looking maid in neat uniform. So that was all right. She drew a sigh of relief.

David said, ‘Here we are. Don’t look so nervous. I know they’ll love you.’

He looked down with infinite tenderness and some awe at the little person over whom he held the umbrella. She was so perfect, so beautiful; innocent and shy, like a delicate woodland creature. Whenever he saw her or thought about her he felt a great surge of love that was almost like sorrow. How could he deserve her? The words of a hymn ran through his mind: she was his pearl of price, his countless treasure. He wanted to do great deeds to prove himself worthy of her. It was lucky in a way that there was a war, because opportunities to conquer mountains and slay dragons were scarce in the ordinary world. But surely in fighting for mankind’s freedom, he might achieve something to lay at her feet.

She glanced up at him through her thick dark eyelashes and said, ‘I’m all right.’ And put her chin up and walked in. She had courage, too, he thought, folding the umbrella and following her.

It was Sadie Hunter’s way to stay in the background, to watch and listen before she made up her mind about things. As the middle child, overshadowed by her elders – David’s magnificence, Diana’s beauty, and Bobby’s charm – and with two boys after her, she had always stood rather apart within the family.

She felt she was not pretty enough to make a success of being a girl – especially as everyone must compare her with Diana. She would be eighteen in two weeks’ time, and had never had a single beau. She did not particularly want one. She visited wounded officers at Mount Olive convalescent hospital as part of her war work. Some of them died. In wartime, it seemed a perilous thing to become fond of a man.

It was wonderful to see David home on leave. She saw the change in him. He had been in battle, which she thought tremendous, though also sad and rather horrible. He had seen men die – perhaps had killed men himself. Something like that must change a person. Peter clamoured, as a nine-year-old might, to know how many Germans he had killed. David avoided the question lightly, but Sadie would never have asked him that.

It was a shock that he was engaged to be married. Sadie hung back and examined the person he had brought to see them, who would one day be his wife and Sadie’s sister-in-law. She was very pretty, that was the first thing one noticed: dark hair, white skin, large eyes; the sort of rosebud mouth men admired, and a very long neck. She had on a pretty dress of dusky-pink wool, the hem a modest two inches above the ankle, showing pink suede buttoned boots – not sensible wear, Sadie thought, for a day of unremitting rain.

So much for how she looked; but what was she like? She smiled a great deal, and seemed to say just the right thing to everybody, but that could be just the good manners of a well-brought-up young lady. Probably it was foolish to expect any deeper insight into a person’s character on a first meeting. At any rate, David obviously adored her, and that was enough for Sadie. She would do everything she could to get to know and love her. She owed it to David.

Diana was also examining Sophy’s appearance. The dress was up to the mark, the colour well chosen, the style not too elaborate. Either Sophy or her mother had good taste. And Diana loved the boots. David ought to have got a taxi from the station.

David, she thought, had grown rather grim – not that he had ever been jolly, the way Bobby was – but there was something about his eyes, and the way he avoided certain questions. He was obviously besotted with Sophy. Diana found herself a little surprised. He had easily resisted the charms of her friends, many of whom had been smitten with him. She saw nothing out of the ordinary about Sophy.

Well, perhaps she grew on one. It had taken Diana a long time to find out the true worth of Charles Wroughton, Lord Dene. Too long. She felt she had only just started to appreciate him properly when he was killed in action at Festubert last May. So she would withhold judgement on Sophy. Not that it mattered anyway. It was hard to take an interest in anyone else’s marriage now Charles was dead.

William and Peter, having inspected ‘David’s crush’ and found her as uninteresting as all creatures of her age and sex, sidled out of the room about their own affairs, and the others disposed themselves around the fire to talk politely of war and weddings until Ada should come in and announce luncheon.

‘What do you think of her, then?’ Cook asked Ada, when she came back to the kitchen.

‘Seems a nice young lady. Not as beautiful as Miss Diana, of course, but quite pretty. And Mr David’s mad for her, you can see that.’

‘So we shall have a wedding,’ Cook said. ‘Well, not us, of course. It’ll be her family arranges everything. Up in London, I suppose. Two houses, they got,’ she added, with a sniff, torn between approval and envy.

‘And what then?’ Ada said. ‘With him away at the war?’

‘Probably stay on with her parents,’ Cook said. ‘Won’t seem hardly like a marriage at all, to my mind.’

‘Oh, but it’s ever so romantic,’ said Emily, the kitchen-maid. She clasped her hands in rapture. ‘The brave soldier going into battle, wearing the favour of the beautiful maiden he loves.’

Cook sighed. ‘I don’t know where you get all that nonsense from, I really don’t.’

‘Everybody loves a wedding!’

‘Well, you won’t be invited, so you needn’t get worked up about it,’ Cook told her.

‘Lucky if there’ll be a wedding,’ Ethel said.

‘What d’you mean by that?’ Ada said quickly.

Ethel wouldn’t elaborate. ‘They’re sitting down,’ she announced instead. ‘Are we taking the soup in, or what?’

‘Oh, my goodness, go, go!’ Cook said. ‘Don’t keep ’em waiting! What’ll Miss Oliphant think?’

Ada and Ethel exited with their trays, and Cook stood a moment, frowning. No wedding? What was Ethel talking about? Was she referring to poor Lord Dene being killed? Or perhaps her own beau that was killed by a wicked Zeppelin bomb. Ethel had been very quiet since it happened, quite a changed character – not that she hadn’t needed changing. Too full of what the cat cleaned her paws with, that’s what she’d been before, and heading for trouble with her flirty ways and so many soldiers wandering about the place.

Still, Cook would almost have preferred to have the old Ethel back, rather than this stone-faced stranger. You had to forgive her a lot. But she’d no right putting a damper on Mr David’s engagement. It was unlucky to talk like that. No wedding …?

‘Do you want them taties mashed?’ Emily broke into her reverie. ‘Will I do it, so?’

Cook snapped back to the present. ‘You will not – they’d be all lumps. Fetch me the butter. And stir that gravy, and get the hot plates out of the oven. They won’t be long over a drop o’ soup.’

Edward was sorry to miss the opportunity of welcoming David’s fiancée into the family. He was anxious to do the thing properly, remembering the awkward first meeting with Charles Wroughton’s family, how frosty and disapproving Lady Wroughton and some of her relatives had been. But he would have opportunities of seeing her when David had gone back to France. The Oliphants were bound to invite him and Beattie to dinner, and they would have to reciprocate in kind. The wedding itself must be a distant prospect, given that David was in no position to support a wife; so distant, that the nuptials of his eldest son seemed curiously irrelevant to him, compared with the war.

He had a late meeting at the Treasury that evening, so he took supper at his club first. He met Lord Forbesson, from the War Office, bent on the same mission, and they went into the dining-room together, talking about the weather.

‘At least we can forget about Zeppelins for a couple of weeks,’ Forbesson said, as they studied the menu.

‘How so?’ Edward asked.

‘Next full moon isn’t until the twentieth.’

‘Oh, of course,’ said Edward. Zeppelins needed moonlight to navigate by. ‘I should have remembered.’

‘One finds oneself aware of the phases of the moon quite subconsciously, these days,’ said Forbesson. ‘And with any luck, there might be bad weather around the twentieth. A fog in January isn’t too much to ask. Or a good rough storm. But the Zeppelins aren’t so much of a problem, in any case.’

‘The fear they engender is out of all proportion to the damage they do,’ Edward agreed, ‘but I would have thought—’

‘I mean,’ said Forbesson, ‘not a problem to us. The people don’t blame the government for the Zeppelins. But there’s bound to be a lot of bad feeling when conscription kicks off. It goes against our basic national characteristic: sheer bloody-mindedness.’

‘How far along are you?’

‘Asquith introduces the Bill this evening,’ said Forbesson. ‘There’ll be no opposition. We should get Royal Assent by the end of the month.’

‘It only covers unmarried men, doesn’t it?’ said Edward.

‘Yes, but I doubt that will last more than a few weeks. We’re forty thousand men short in France now, and we mean to mount a big push this year. The married men will have to turn out as well if we’re to get the manpower we need. We have to leave out Ireland – things are too volatile there. And there’ll be thousands looking for exemption: widowers with children, starred occupations, ministers of religion …’

‘You anticipate a rush of young men to be ordained?’ Edward said, amused.

‘It wouldn’t surprise me,’ said Forbesson. ‘When it comes to finding new methods of shirking, the man in the street has wiles approaching genius.’

‘So when does it happen?’ Edward asked.

‘Assuming the Bill goes through to our timetable, we’ll call the first classes at the end of the month, and they’ll have to report on the second of March.’

‘That’s quick work.’

‘We’ve been planning this for months, ever since it became obvious the Derby Scheme wasn’t going to cut the mustard. But it won’t affect you, will it? Your two eldest have volunteered already, and your younger boys are below age, I think?’

‘Yes,’ said Edward. ‘But my secretary’s twenty-eight.’

‘Ah,’ said Forbesson. He knew how much Edward thought of Warren. ‘Bad luck.’

It was very late when Edward got home – something that had become more frequent since the war had picked up pace. The servants had gone to bed but the hall light had been left on for him and he let himself in with his latch-key. He looked in at the drawing-room, where the fire had been banked. A decanter had been left out with some sandwiches wrapped in a napkin, but he wasn’t hungry, and trod his way wearily up the stairs. It had been a long day. The Treasury meeting had been hard work. War was an expensive business, and acceptable ways of raising money required a lot of thought and planning.

The lamp on his side of the bed was alight, but Beattie seemed to be asleep, so he went into the dressing-room to undress so as not to disturb her. But when he returned to slip into bed, he saw she was awake, staring at the ceiling; and he remembered what he had forgotten since the morning, that it was the day of David’s visit with his fiancée.

Beattie had been upset that he was spending his leave with the Oliphants, and only granting his family one day of it. David was very special to her, and Edward always had to step carefully around anything concerning him.

‘I’m sorry I missed it,’ he said. ‘Did it go all right? What’s Miss Oliphant like?’

There was a long pause before she answered, in a dead voice, ‘She’s a pretty girl.’ It sounded like a condemnation.

He studied her blank face, trying to deduce the problem. ‘Was she well-behaved? Did you like her?’

‘Of course she was well-behaved,’ Beattie said, avoiding the other question. She had learned the hard way to school her countenance and give nothing away, and it had come in useful over luncheon. She had smiled and talked graciously to Sophy Oliphant, while inside she seethed. Why was David entranced by this commonplace girl? It was true that other men, lesser men, wanted nothing more than a decorative cypher to keep house for them. The girl had a pretty face, youth, and well-brought-up manners – but that was all. How could her darling, her most precious son, throw himself away on such a mannequin? He was so young, not yet twenty-two, and he was tying himself for life to a girl who would never understand what she had caught.

Sophy had smiled, and looked modest and shy. Beattie had sensed the shadowy presence of an expensive governess behind that polished façade. Sophy would always say the right thing. No doubt one day she would ask – modestly, shyly – if she could call Beattie ‘Mother’, and Beattie would long to break that swan-like neck.

She knew she should be grateful. There were two of her acquaintance in Northcote whose sons were dead. David had come back unharmed. But he had not come back to her. From now on, Sophy would have the love that previously had been Beattie’s. Sophy would be the one he chose to be with. It was hard to bear – and harder still because they were feelings she could not express to anyone, because no-one would understand. Not even Edward.

He saw the compression of her lips, as though she were holding back words that wanted to burst out. ‘What is it, dearest?’ he asked her gently.

And despite herself, she answered, ‘It feels like the end of everything.’

He didn’t understand. ‘But you’ll have a lovely daughter- in-law. In time, grandchildren.’

No answer.

‘It’s a beginning, really, not an ending.’

No answer. She closed her eyes so that he shouldn’t read them.

Edward put out the light, lay down, turned on his side and tentatively touched her shoulder, hoping he might hold her, comfort her. But at his touch she turned away, hunching her back against him, moving to the furthest edge of the mattress.

The rejection hurt him. His heart ached with loneliness, but also with concern for her. He lay very still, so as not to come in contact with her, since he knew she didn’t want to be touched. Despite his tiring day, it was a long time before he fell asleep. He didn’t think she was asleep, either, but it seemed there was nothing he could do for her – or for himself.

Bobby eased his way through the crowd in the Lamb and Flag in St Giles’, carefully protecting his pint of beer against impulsive elbows. He spotted his friend Horsey – inevitably called Dobbin – already seated in one of the little alcoves that made the pub so cosy. Trust Dobbin to be early, he thought. Very reliable chap, old Dobbin.

‘What-ho, Dob! There you are, old thing! Do you realise you’re sitting in the very spot where Thomas Hardy wrote Jude the Obscure?’

Dobbin looked startled. ‘Am I? Did he?’

‘No idea,’ Bobby admitted. ‘You being such a swot, and having a huge brain, I assumed it’d be the seat you’d pick.’

‘I don’t really know anything about it. I just thought it was quieter in here than the Bird and Baby,’ Dobbin admitted.

It was what the undergraduates called the Eagle and Child. ‘Bound to be,’ said Bobby. ‘That’s where the hearty St John’s roughs do their quaffing.’

‘Quaffing?’ Dobbin wrinkled his nose at the choice of word.

Bobby sat down opposite him. ‘You know what quaffing is, don’t you? Much like drinking, except more of it ends up on the floor.’ He punched his friend’s arm cheerfully. ‘It’s so good to see you! It’s been an age.’

They had been ‘best pals’ in school, but since coming up to Oxford, their paths had flung apart. Bobby had gone to Balliol and Dobbin to Brasenose; and then Bobby had volunteered. He’d spent three months doing basic training on a very chilly hilltop in Surrey, before transferring to an officer training unit, which, fortuitously, had turned out to be accommodated in his old college, back in Oxford.

‘I see you in the distance now and then,’ said Dobbin. ‘Hurtling by in someone’s motor-car. Generally making a lot of row, it has to be said.’

‘One has to make a row in a motor-car – it’s half the fun.’ He was studying Dobbin closely as he spoke, and knew his friend was doing the same to him. He felt a sort of pang – he and Dob had been as close as brothers all through school, and now there seemed a distance between them.

Echoing his thoughts, Dobbin said, ‘You’ve changed, y’know.’

‘Have I? I feel pretty much the same.’

Dobbin shook his head. ‘You think you do, but you don’t. You’re much older.’

‘It’s the beer and cigarettes. Copious consumption thereof. You’re older, too. I suppose that’s the greasy grind.’ He grinned. ‘What a surprise it must have been to the Brasenose dons to find they’d got a genuine scholar on their hands instead of another beefy sportsman!’

‘You always talk as if I’m a complete rabbit,’ Dobbin complained, ‘but I’m a pretty fair cricketer. I don’t suppose you’ve been on a playing-field in the last eighteen months.’

‘I’ve been too busy,’ Bobby said. He extended his arm to show the ring of braid and the single crown on the cuff flap. ‘Got my pip! You’re looking at Second Lieutenant R. D. Hunter, in all his glory.’

Dobbin peered at it suspiciously. ‘Is it pukka?’

‘Course it is! Gazetted yesterday. I’m the real thing, old Dob. What d’you think?’

‘I never doubted for a moment you’d make officer. You were born for it. Congratters.’ He shook Bobby’s hand across the table. ‘So, what’s next in the illustrious career? Back to the Middlesex?’

‘Well,’ said Bobby, ‘you remember we used to talk about what we wanted to be when we finished at Oxford?’

‘And you said you wanted to be a tight-rope walker.’

Bobby nodded. ‘I’m going for the next best thing. I’m seconded to the RFC. I start my training tomorrow.’

‘Flying?’ Dobbin looked wondering, and then smiled. ‘Yes, I can just see it. It’s your métier – flying so high with your head in the sky.’

‘Looking down on the poor bloody infantry in their trenches.’ He lowered the level in his glass, then said, ‘I bet you’re wishing now you’d volunteered too, when I did.’

‘You know my father would never have allowed it.’

‘I didn’t think mine would either – that’s why I didn’t tell him until afterwards.’

‘I’m not like you. You never seem to care about consequences, but when my pater gets in a bate with me, I shrivel like a salted snail. Can’t help it.’ He looked down. ‘Lacking pluck, I suppose.’

‘You don’t lack pluck.’ Bobby jumped to his defence. ‘You’re just thoughtful, so you see things coming. I’m too thick-witted to think ahead.’

Now Dobbin smiled. ‘You know that’s not true. Anyway,’ he became grave again, ‘it’s out of my hands now, from what I hear. It’s not just a rumour, is it? They’re bringing in conscription?’

Bobby nodded, eyeing his friend with sympathy. ‘Our CO says they’ll be calling up the first classes within weeks. I’m sorry, Dob.’

He thought it must be awful to be coerced, rather than to volunteer; and he wasn’t sure Dobbin would have volunteered anyway, even if his father would have let him. He was the bookish type, whatever he claimed about his cricketing prowess. Always thinking. You couldn’t imagine him with a rifle, shooting at Huns – he’d be more likely to want to discuss Kant and Nietzsche with them.

‘We’ve all got to do our bit,’ Dobbin said sadly. ‘I know that. It’s just that I think the army’ll be getting an awfully poor bargain in me. You know how cack-handed I am. Probably shoot the CO by mistake.’

‘Oh, they teach you not to do that sort of thing in basic training,’ Bobby said lightly. ‘And, look here, Dob, when you’re through basic, why not transfer to the RFC, like me? I know you’d be a bit behind me, but we might end up in the same unit, and the flying boys are much more relaxed about seniority and suchlike, so I’ve heard. You don’t want to go into the trenches, anyway. Awful muddy places, trenches. Shocking hard on the trouser turn ups, y’know, your Flanders mud.’

Dobbin shook his head. ‘It’s no use. I’d never make a pilot,’ he said. ‘My eyesight’s not good enough.’ He saw Bobby about to protest, and went on, with forced cheerfulness, ‘I’m not glamorous enough for the RFC, anyway. I’d bring down the tone. I suppose I’ll end up where I’m sent, and they’ll have to put up with me. So what happens now? Are you staying in Oxford?’

Bobby recognised a change of subject when he heard one. He felt obscurely angry on Dobbin’s behalf, though he hardly knew why. The war would not be kind to chaps like him. ‘No, I’ll be off tomorrow – that’s why I wanted to see you today. I had to report to the Air Ministry yesterday, and a jolly helpful captain laid it all out for me. I totter up tomorrow to the School of Military Aeronautics in Reading for basic training. That’s a ground school, lasts about four weeks. And then, assuming I don’t make a complete ass of myself, I’ll be transferred to flight school, and actually get off the ground at last.’

‘And when will you be a qualified pilot?’

‘Flight training’s three months, more or less – depending on how you take to it, duck to water, or ostrich on roller-skates.’

‘You for the duck, definitely. And then – France?’

‘Most likely. I mean, they do have aeroplanes in the eastern theatre, and there’s the home-defence johnnies, but the greatest need is obviously on the Western Front. So, come May or June, I shall be doing my quaffing in the estaminets and – look out, Mesdemoiselles!’

‘Speaking of which …’ Dobbin said, suppressing an odd twinge of envy – for, really, he had no desire to go to France, not like that. A cultural tour in peacetime, to visit the museums, monuments and art galleries, perhaps, but in khaki and carrying a rifle? Non, merci!

‘Which which is that?’ Bobby queried.

‘Mesdemoiselles. Have you been breaking any hearts lately?’

‘Oh, Lord, no – there hasn’t been time. But I believe discipline is much looser in the RFC, and spare time much more generous, so perhaps I shall be putting a toe in the water soon. What about you?’

Dobbin blushed a little. ‘Well,’ he began cautiously. ‘There is someone—’

‘You dog!’

‘Nothing like that,’ Dobbin said hastily. ‘She’s a very nice young lady who’s studying English literature at Somerville. Her name’s Mary Talbot. Her brother’s at Brasenose, and we met at a tea-party in his rooms. All very respectable.’

‘I’m sure it is. Is she nice?’

Dobbin became inarticulate. ‘Nice? She’s – she’s—’

‘Beautiful as an angel?’ Bobby suggested.

‘Well, she is,’ Dobbin said. ‘Dark hair and the most wonderful dark eyes, and such a gentle, spiritual look to her face.’

‘Dob, you’ve caught it badly,’ said Bobby, seriously.

‘I can’t think what she sees in me,’ Dobbin confessed.

‘She’s lucky to have you. In fact, I’d love to meet her, to make sure she’s worthy of you.’

‘I did say I might bring you to see her, if you had time. She’s waiting at the Botanic Gardens.’

‘At this time of year?’

‘It’s warm in the greenhouses,’ Dobbin pointed out.

Bobby caught the train to Reading the next morning in reflective mood. He had been impressed with Miss Talbot. The three of them had walked for an hour or so in the warmth of the greenhouses, while a very January rain coursed down the glass roofs above them. They had talked of Rupert Brooke, and Webster and Elizabethan drama, and the war had not been mentioned. She was, as Dobbin had promised, handsome, with a quiet understated beauty that he found affecting. There was something serene and strong about her, and she carried on the conversation in such a frank, straightforward manner that he found himself forgetting – almost – that she was a woman. There were no wiles, or guiles, or foolish foibles about her. He found himself envying Dobbin. He had never known a woman like her – a woman, he felt, whom one could really make a friend.

They had walked back together, sheltering under Dobbin’s enormous umbrella, and left her at the gates of Oriel. (The Somerville buildings, being adjacent to the Radcliffe Infirmary, had been commandeered by the War Office early in 1915 for use as a war hospital, and the undergraduates had been relocated to Oriel.) They had met again in the evening, for dinner at the Florence Restaurant, making a quartet with her brother for respectability’s sake. The evening was jolly, and she showed that she could laugh, too, though Bobby had sensed an underlying seriousness to her, which had made him modify his own high spirits. It emerged in conversation that she helped out at the hospital between reading and lectures. With her calm, gentle manner, he had thought she would make an excellent nurse.

As the train crawled with war-time lassitude towards the beginning of his new life, he imagined what it must be like to win the love of such a woman. He wondered what would happen to them all in the next months and years. Dobbin would be called up, he would have to go, and she would be left behind to fret and worry. Would they get engaged before Dob had to leave? A lot of chaps did. Some in the Middlesex had even got married.

He was glad for Dob, but on the other hand, he wouldn’t swap places with him for the world, if it meant not learning to fly. He was going to fly! That was excitement enough, he decided, to be going on with. All the other stuff could wait until the war was over.

A Police Bill was going through Parliament, and there was agitation, from former suffragettes and their sympathisers, to have some provision for women police included. An MP, Frank W. Perkins, was campaigning for women police to be appointed, sworn in, and given power of arrest, just like the men. The Church was broadly behind him, and some senior policemen, even one chief constable, had said that the women police had made a great difference to the streets.

‘I hope we have,’ Edward’s sister Laura said to her friend Louisa one day, as they got ready to go out, ‘but it hasn’t been easy.’

‘I think it’s getting more difficult,’ said Louisa, trying to wrestle her unruly hair into something more suitable for a woman police officer. ‘Don’t you think the lower orders are less polite and obedient than they were when we started?’

‘They’re getting used to the sight of us,’ said Laura.

‘I think they’re bolder in every way. Especially the women. Now their men are away, they don’t seem to have any restraint.’

‘You may be right,’ Laura said. ‘I think the war has eroded a certain natural deference. If it weren’t for the badge and the armband, I don’t suppose they’d heed us at all. What was it the sergeant said to us the other day? “If you ask a group of bystanders to move on, never look back to see if they’ve obeyed you.”’

‘But

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...