- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

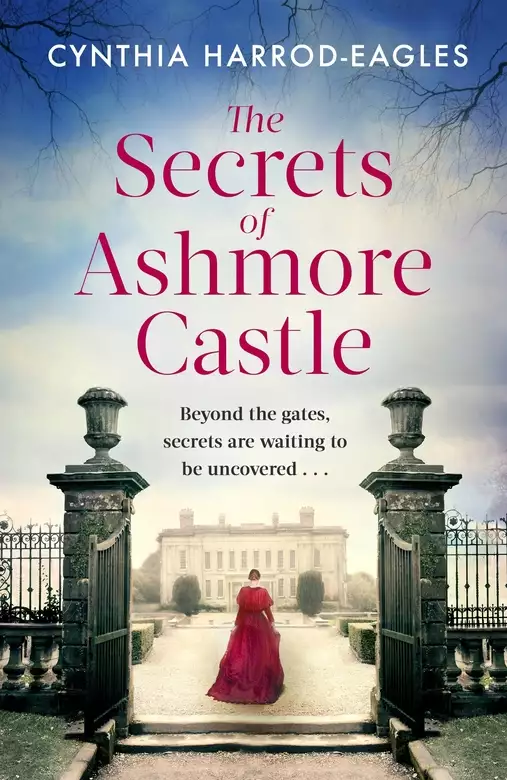

The brand new series, perfect for fans of DOWNTON ABBEY, from the author of the hugely successful MORLAND DYNASTY novels

Behind the doors of the magnificent Ashmore Castle, secrets are waiting to be uncovered . . .

1901. When the Earl of Stainton dies in a tragic hunting accident, Giles, the eldest son of the noble Tallant family, must step forward to replace him as the head of the family. But Giles has avoided the Castle and his stifling relatives for years, deciding instead to forge his own path away from the spotlight. Now, he must put aside his ambitions and honour his duty to the family.

With their world upended, the Tallants and their servants struggle to find their place in the house - and society - once again. And Giles realises that, along with the title and the castle, he's also inherited his father's significant financial troubles that threaten the security of his entire family.

In Kensington, Kitty Bayfield, the painfully shy but moneyed daughter of a Baronet, has just left school with her penniless companion Nina. Nina captures the new Earl's heart, but only Kitty can save his family from their debts, and soon Giles must choose between his duty and his heart . . .

The Secrets of Ashmore Castle is the first in a brand new historical family drama series, filled with heartbreak, romance and intriguing secrets waiting to be uncovered. The perfect read for fans of Downton Abbey, Bridgerton and rich period dramas. Don't miss the next book, The Affairs of Ashmore Castle.

Release date: August 12, 2021

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Secrets of Ashmore Castle

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

It was a hard walk up the hill, especially carrying a valise. Sometimes she had to pick her way through muddy hollows, where hoofs and wheels had churned the ground. The recent long, cold spell had broken, and it had been mild and wet, though today there was only a fine drizzle. At one point, she had to step aside as two grooms posted past, each riding one dapple grey and leading another. Carriage horses being exercised, she thought wisely, noting that they matched. They pranced and lifted their knees high, trying to toss their heads, and seemed very big, their weight displacing the air. She was prepared to smile and wave to the men, but they did not look at her as they passed. Horsemen were usually friendly, she had found, but an earl’s grooms were above ordinary mortals.

The big white house on the hill looked down over the Ash valley and dominated the view from the village of Canons Ashmore. It was called Ashmore Castle – she didn’t know why – but was always referred to as just ‘the Castle’. There was prestige in getting a place there, and when you left, a reference with that name on it was worth a lot. She followed the minor path round to the back, as instructed, and arrived eventually in a yard behind the kitchens where she discovered two men in footman’s livery, smoking. They had chosen a spot where the overhang kept the drizzle off them; they were jacketless, with long green aprons over their striped waistcoats and shirtsleeves.

One was tall and thin, with a hard, noticing face and rather bulging eyes. The other was shorter, plump, and with a face that denoted either good humour or stupidity.

‘Hullo, what have we here?’ said the thin one. His raking look took in the valise. ‘Fresh blood?’ He had been lounging with one foot up on the wall behind him. Now he pushed himself off and stood straight, continuing to examine her in a way that made her feel he could see right through her clothes. ‘Who are you, then?’

‘I’m the new sewing-maid. Dory Spicer.’

She looked at the plump one enquiringly.

‘William,’ he said, ‘William Sweeting.’

‘Nice to meet you, William,’ she said.

The thin one gave a derisive snort. ‘Ho, aren’t we polite?’ he mocked, in mincing tones. Then he thrust his face closer. ‘You listen to me, Dory Spicer – what sort of a name is Dory, anyway?’

She didn’t answer. She hated her name, Dorcas, and never let anyone find it out if she could help it.

‘Well, I’m James,’ the thin one went on, ‘and I’m first footman, so I’m an important person to get on the right side of. Be nice to me, and you could go far. I run this house.’

‘Isn’t there a butler? I heard there was a butler.’

‘Oh, Mr Moss,’ James said witheringly, and left it at that, as though nothing more needed to be said about him.

She looked at William, who swallowed nervously and said, ‘Mr Moss has been here for ever, nearly. Years and years. Him and his lordship go right back.’

‘What’s his lordship like?’ Dory asked, to encourage him.

James intervened. ‘You don’t need to know that. You’ll never see him. You’d best go and report to the housekeeper, Mrs Webster. Watch out for her – she’s a Tartar.’ He grinned at her, and his face was so thin she could see the muscles move and rearrange. It was unnerving. ‘Sewing-maid, eh? Watch you don’t go the same way as the last one.’

She knew he wanted her to ask him what that was, but she clung to one last grain of defiance. She wouldn’t ask him. Instead she said, as if meekly obedient, ‘All right,’ and went towards the nearest door.

‘Not that one,’ James called sharply. ‘That’s the kitchen. That one – rear lobby. Go through it and turn left, housekeeper’s room’s at the end.’

She changed direction and muttered, ‘Thanks,’ without looking at him again.

‘You don’t want to go in the kitchen without being invited,’ he called after her. ‘Lots of sharp knives in the kitchen.’

He’s just trying to scare you, she told herself, as she scurried past. But she didn’t like the hints of a divided, fractious household. He might be just a troublemaker, she thought, stepping through the rear lobby, with its smell of wet mackintoshes and boots, but that didn’t mean it wasn’t so.

It was a good day for hunting: the mild smells of earth rose damp and sweet through the thready mist, and the scent was breast high. Hounds were running well – a pocket handkerchief would cover them, as the saying was – and the clamour of their music echoed eerily on the winter air.

Behind them, the field galloped, strung out as the pace increased. The Earl of Stainton was well up with the leaders. Hunting was his passion. It was not about the kill, it was about the run: the speed, the sound of slamming hoofs and snorting breaths, the thrust of great muscles beneath him, the sting of the wind past his face. Joy filled him, fierce and exhilarating, blotting out any troubled thought. For a little while he could forget himself, his difficulties and responsibilities, and become a creature of pure sensation. He and the horse and the moment were one, a united thing of taut, glorious perfection.

The fox was old and cunning, and had led them a dance, but the earl had hunted this country since he was eight years old, and carried a map in his head of every contour and copse. It was his land, and he knew it as well as the fox did. He felt instinctively that Charlie was heading for the farm at Shelloes, where the large pig yard would foil the scent. Stainton took his own line whenever possible. He turned aside, sending Jupiter thundering diagonally across the slope. Ahead was a big blackthorn hedge, a formidable jump, and the approach was awkward, but it was well within Jupiter’s scope. Two paces away, the big bay pecked slightly, but Stainton pulled his head up, gave him a thwack behind the saddle, and shouted, ‘Come on!’ Jupiter grunted, thrust off, and rose magnificently to the challenge.

They soared. The earl cried out, ‘God!’ in simple ecstasy.

In the parlour of a small house in Ridgmount Street in Bloomsbury, four hands freed the notes of Schubert’s Sonata in C from the keys of the piano in a steady, accomplished rhythm. Dust motes swirled in the stream of pale winter sunshine that filtered through the net curtains, and glinted on the two golden heads, one middle-aged, one young.

Suddenly Mrs Sands threw up her head and cried softly, ‘God!’

The music tumbled to a halt.

‘Mummy? What’s wrong?’ Chloë asked.

Molly Sands had put both hands to her head. Now she opened her large, pale blue eyes, and took a shaky breath. ‘It’s all right. I’m all right,’ she reassured automatically.

Chloë continued to look at her anxiously. ‘Is it a headache?’

‘No – not … I just felt … I don’t know. Strange. As though …’ It had been as though she was falling – a black, swooping sensation. But it was momentary, and she did not like to see her daughter alarmed. She grew brisk. ‘It’s passed now, whatever it was. Begin again, please, from the triplets.’

Chloë didn’t immediately obey. She and her mother were very close; and there were just the two of them. They lived in a small but comfortable way on Mrs Sands’s earnings as a piano teacher. If anything happened to her mother …

‘Mummy?’

‘It was nothing. A moment’s dizziness. I’m quite all right now,’ Mrs Sands said firmly. ‘Begin, please.’

The music resumed.

The earl’s groom, Archer, following his master on the second horse, Tonnant, saw Jupiter’s knees strike the dense top of the hedge. Recently cut, it was bristly and unyielding. The enormous impetus of his jump flipped the horse over in a complete somersault. The earl went flying off. Archer jerked Tonnant away and aimed him at a spot further down the hedge, to avoid landing on whatever might be on the other side. The hedge was lower here, and Tonnant cleared it easily. His blood was up and it took half a dozen paces before Archer could check him and turn. By that time, Jupiter had already struggled to his feet, and was standing, trembling, one forefoot held off the ground, the saddle twisted round under his belly.

Beyond him, the earl was lying in a crumpled heap, unmoving. He was an experienced rider, hunted three or four times a week, had taken hundreds of tumbles in his time. He knew how to fall, should have got straight up. Must have winded himself, Archer thought, sliding down. And yet he knew. Something about the stillness of the body, the awkward angle of the neck … A cold dread settled in his stomach.

Tonnant was excited, threw up his head, snorting, would not be led nearer. But two other riders came over the hedge where Archer had jumped – Mr Whitcroft, a local farmer, and his son Tim.

‘What the—?’ Whitcroft exclaimed, pulling up so sharply that Tim’s horse cannoned into him. Both men quickly dismounted. Whitcroft took Tonnant’s reins from Archer and cried, ‘Go to him!’

Archer knelt on the bumpy grass, feeling strangely remote, as though the world was at the wrong end of a telescope. The earl must have hit the ground at an awkward angle. His head was twisted to one side, and one blank eye seemed to peer up at the sky. There was nothing to be done. He was gone.

Archer stood up shakily, met Mr Whitcroft’s gaze, and shook his head. Tim looked from one to the other and said, ‘He’s not—?’

‘God rest his soul,’ Archer replied, and Tim gulped.

Whitcroft turned to his son and said sharply, ‘Ride to the Castle, quick as you like, raise the alarm. Bring help.’

Archer roused himself. ‘Take Tonnant,’ he said. ‘He’s faster’n your plug.’

The boy looked white and shaken, but he had wits enough to obey, to separate out Tonnant’s reins, and cock his knee for Archer to leg him up. He was away while still feeling for his off-stirrup, Tonnant leaping straight into a gallop, still excited, eager to be moving again. Archer hoped the boy could stick on. Maybe he should have gone himself. But he couldn’t leave his master.

‘Shouldn’t we straighten him out?’ Whitcroft said, the shock evident in his voice.

Mr Whitcroft was right, Archer thought. You couldn’t leave the earl all bunched up like that. ’Twasn’t respectful. He straightened him out as best he could, then rose again awkwardly. Whitcroft took off his hat, and Archer followed suit. Must see to the horse, his groom’s instincts told him, but this moment had to be observed.

‘It’s the way he would have wanted to go,’ Mr Whitcroft offered tentatively.

‘Yes, sir,’ Archer said again. It was true, he thought. Not old and feeble in his bed, but with a horse under him and the damp winter air on his lips.

Now there was nothing to do but wait.

The head man, Giddins, took charge when the sweating Tonnant skidded into the yard and his rider almost fell off, babbling his news. By the time the butler, Moss, had been summoned, Giddins had sent off four men to bring back the body and two to help with the horses, and was ready to cut through Moss’s immediate paralysis with urgent, respectful suggestions.

‘Doctor’d better be sent for, Mr Moss.’

‘Yes. Of course.’

‘And the undertaker.’

The word shocked Moss. ‘But we don’t know that he’s dead yet!’

Giddins gave him a steadying look. Archer was no fool. He’d seen dead men before, and dead horses. He wouldn’t make a mistake like that. ‘Better Mr Folsham’s on hand when he’s wanted. Nobody upstairs needs to see him waiting.’

‘Yes, you’re right,’ Moss said.

‘And rector,’ Giddins went on. ‘He’ll be wanted. And Mr Markham did oughter be told.’ Markham was the agent.

Moss pulled himself together. He had his position to consider. Couldn’t have a stableman telling him what to do. ‘I will see to everything,’ he said. ‘I must tell her ladyship at once, before rumour reaches her.’ But he paused, all the same, staring at nothing. ‘He was such a good rider,’ he heard himself say, puzzled.

Already it was the past tense for his lordship, Giddins noted. ‘Accidents happen,’ he said.

William George Louis Devereux Tallant, fifth Earl of Stainton, came home to Ashmore Castle for the last time on a withy hurdle, with estatemen pulling off their caps as he passed, and women coming to their cottage gates to stare. He was carried into the rear yard, where a number of servants had gathered in worried or excited groups, whispering among themselves. Dory was among them, and found herself quite close as the litter passed, close enough to see the white face. That James was wrong, she thought. I did see him. Much good would it do her! She wondered if her job was safe, and dismissed the thought. There’d be all those armbands to sew on, and who knew what else in the way of mourning clothes? They’d need a sewing-maid now more than ever.

The earl’s lady received him with white, stinging fury, though from long training, nothing showed on the outside. He had made her a widow – a dowager! How dared he? It had not at all been in her plans to be widowed at the age of forty-nine. Stainton was only fifty-two, and in stout health. She had expected him to last for many more years, and when the time came, to go in an orderly fashion, with plenty of notice. She had imagined a dignified death-bed scene, the whole family gathered in respectful silence to hear his last words and witness the last breath. Not like this! Not carried in, broken and muddy, by yokels! Nothing was arranged! No plans were in place! How could he do this to her? She had done her duty by him, and now he had reneged on the deal. She was beside herself with rage.

‘A telegraph must be sent to his lordship,’ she said, managing to keep the tremble out of her voice. Moss, the butler, would have thought it a tremble of grief rather than anger, but she did not show emotions to the servants, not even understandable ones. Her eldest son, Viscount Ayton, was in Thebes, attached to a group conducting excavations on behalf of the Egyptian Department of Antiquities. ‘He must come home at once.’

She met the butler’s eyes and read the question in them. How long would it take Ayton to get back from Egypt, and could the funeral be held off that long? Thank God it was winter. A cascade of considerations flooded through her mind: the people who would have to be informed, the visits of condolence that would have to be endured, the funeral to arrange, the ramifications of will and finances, succession and titles … It went on and on. Damn Stainton for doing this to her!

‘I will see to it at once, my lady,’ Moss said, with a tremble in his voice. He could afford to show emotion – it was laudable in a servant.

The earl’s unmarried daughters, Lady Alice, fifteen, and Lady Rachel, sixteen, had been hunting that day, but the point had been so fast that when hounds checked at Shelloes – the earl had been right about Charlie’s destination – no-one yet knew about the accident. Josh Brandom, groom to the young ladies, did not wait to see if the scent would be picked up again. Pharaoh and Daystar had had enough, he decreed. It was time to go home. They did not argue with him. He had Archer’s authority, and Archer had their father’s.

Josh insisted that they trot all the way, through the gathering dusk and the increasing cold. It was agony to trot for long on a sidesaddle, but that was also Archer’s orders, as the girls knew: cantering was too tiring for the horses after a day in the field, but they would get cold at the walk. ‘Don’t want chills in our stables,’ Josh said implacably, when Rachel complained and Alice pleaded. ‘When you’re grown-up, you can do as you please.’ He sniffed, the implication being that if they did as they pleased they would be ruining good horses, but it wouldn’t be his problem then.

When there was a hunting party at the Castle, there was always tea in the Great Hall – a baronial anachronism added by their grandfather, useful for large gatherings – but there was no company today, so the young ladies would have theirs in the former schoolroom, which they now used as their sitting-room. Josh took pity on them and let them off at a side door, taking their horses round to the stable-yard himself.

Their first few steps were stiff and painful. ‘My back’s got knives in it,’ Rachel complained.

‘My sit-upon hurts,’ Alice countered.

‘Don’t be vulgar,’ Rachel chided automatically. They started up the stairs. There was no-one about. ‘Never mind – hot baths soon. And boiled eggs, and muffins.’ Always boiled eggs, always muffins after hunting.

‘I hope there’s anchovy toast,’ Alice said, holding her heavy skirt clear of the stairs. Her riding boots were leaden.

‘Won’t be,’ said Rachel. ‘No company. But there might be cake.’

‘Not if Mrs Oxlea’s drunk again,’ Alice giggled.

Rachel shushed her. They weren’t supposed to know about the cook’s weakness – or, at least, they certainly weren’t supposed to speak about it. It wasn’t seemly.

The schoolroom was warm, but the fire hadn’t been made up recently and was dying down. Alice put coal on – the last in the scuttle. ‘Shall I ring for more?’

‘Better not,’ Rachel said. They weren’t supposed to ring without permission, the summoning of servants being a privilege wholly reserved to grown-ups. ‘We can ask when they bring tea.’

But time passed and tea didn’t come. ‘We’ve been forgotten,’ Alice said.

Rachel went to the door, opened it, listened. ‘Doesn’t it sound awfully quiet to you?’ It was always quiet up here, at the top of the house, but it seemed more so than usual. And they hadn’t passed any servants on the way up.

‘We should ring,’ Alice said. ‘I can’t last until dinner time. I shall faint away.’

‘Something’s wrong,’ Rachel said. She closed the door and went back to Alice by the fire. Her anxiety communicated itself to her sister, and they held hands, listening, wondering.

The forge in Canons Ashmore was at the end of the village street. The assistant blacksmith, Axe Brandom, came running out as the rector’s carriage passed and stopped it. The living was a wealthy one, and the rector kept a smart black brougham drawn by a spirited high-stepping bay. Fortunately, the bay knew Axe from many professional encounters and stopped with no more than a snort and one toss of the head, even though it was heading for its own stable.

The rector let down his window and Axe stepped up to it. ‘They’re looking for you, sir, up at the Castle. My brother Josh was here a bit since – went to your house for you, asked me to keep a look-out for you.’

‘I was at the Grange at Ashmore Carr,’ the rector said. ‘Old Lady Bexley—’

‘Yes, sir – they said at your house she had took queer. I hope she’s not—?’

‘Just one of her turns. I sat with her a while and she’s quite all right now. Is someone unwell at the Castle?’

Axe looked solemn. He was a massive young man, with red-gold hair, and golden hairs like wires on his bare forearms. The smithy grime on his face made his blue eyes look brighter. ‘It’s his lordship, sir. Had a bad fall out hunting. They do say as he broke his neck.’

‘Dead?’ The rector was startled.

‘That’s what Josh heard, sir.’

‘Good God!’ the rector said blankly. Just as it had in Lady Stainton’s mind, a flood of consequences and ramifications cascaded through his thoughts. The earl, dead? He pulled himself together. ‘I had better go straight there.’ He craned out of the window to address his coachman. ‘Deering, drive to the Castle.’

Deering, who had heard everything, of course, was ready. He winked at Axe – an inappropriate gesture, the smith thought – and touched the bay with the whip. As it sprang forward, Axe heard the rector mutter, ‘What a terrible thing,’ as he wrestled the window up.

Terrible, Axe thought, as he turned back to the forge and the waiting carthorse. And surprising.

Rachel finally got up the nerve to ring, and they waited in trepidation for it to be answered. No-one had come near them and, going frequently to the door to listen, they had found the house remained ominously quiet. They were sure now something was wrong.

‘We should go down and find out,’ said Alice, always the bolder of the two.

But Rachel was the obedient one, too sensitive, hating to be in the wrong, hating to be told off. ‘Better not. They’d send for us if we were wanted,’ she said.

And at last someone came – not Daisy, who had been their nursemaid and was now the housemaid who generally saw to their needs. It was the head housemaid, Rose, tall, thin, hawk-nosed and always rather daunting, who came in bearing the tea-tray. She regarded them with an unsmiling face – that was nothing new – but with a hint of sympathy in her eyes that was unsettling.

‘Your tea, young ladies,’ she said. ‘I’m afraid you got forgotten in all the fuss.’

‘Where’s Daisy?’ Rachel asked.

‘Couldn’t say, my lady, but she’ll be in trouble when she turns up.’

‘What fuss?’ Alice picked up the word. ‘What’s happened?’

‘I’m afraid I’ve got some bad news for you,’ Rose said. ‘His lordship’s had an accident, out hunting.’

‘Father?’ Rachel said. She reached blindly for Alice’s hand.

‘He had a fall,’ Rose went on. ‘I’m afraid he’s dead.’

She turned her back on them while she set out the tea on the low table by the fire, giving them time to absorb it. Neither of them made a sound. ‘Everything’s at sixes and sevens downstairs,’ Rose said, taking a normal tone, which she thought would help brace them. ‘I had to make your tea myself. Mrs Webster’ll have something to say about it when things settle down. There’s no excuse for not following routine. I did you boiled eggs. There’s no muffins – Cook didn’t make any – but there’s extra toast, and I brought the good strawberry jam. You must be starving.’ She turned at last and saw them still stiff and staring, not knowing – she suspected – how they were supposed to react. ‘Eat your tea. Going hungry won’t help,’ she said. ‘That’s a poor-looking fire. I’ll make it up for you.’

‘There’s no coal,’ Alice said, her voice sticking in her dry mouth.

Rose tutted. ‘That Daisy! I don’t know! Well, come and have your eggs, anyway, before they go cold.’

It was good to have someone tell them what to do. They came and sat, watching blankly as Rose poured the tea.

Alice found her voice, afraid Rose would leave before she had had time to ask anything. ‘How did it happen?’

‘The horse came down, jumping over a big hedge, was what I heard. Jupiter, is that its name? His lordship took a bad fall and broke his neck.’

Rachel made a little sound, an indrawn gasp. Rose’s words seemed to run round the room in a soundless whisper, a little rustling ghost phrase, like mouse feet or dried leaves: broke his neck … broke his neck.

Rose gave a little shiver. Goose walked over my grave, she thought automatically.

At last Alice asked, in a small voice, ‘Do you think … Did it hurt?’ She looked at Rose, her eyes wide and appealing. ‘Does it hurt, dying?’

To anyone else, Rose would have answered, ‘How should I know?’ But she felt unaccountably sorry for the young ladies – daughters of a great house, yes, but the least considered of anyone in it. Shut away up here and kept quiet until they were old enough to be married off – like goods for the market that had to be kept unmarked so’s they’d fetch the best price. So she said, ‘I don’t suppose he’d have known anything about it, my lady. It’s quick, is a broken neck. One second you’re alive, the next you’re dead. No pain at all.’

Rachel reached the end of a train of thought. ‘Mama,’ she said. ‘Shouldn’t we go to Mama? She must be …’ The word upset was the only one she could think of, and it didn’t seem appropriate. Not nearly dramatic enough. How did you feel if your husband was killed suddenly?

‘She’ll be far too busy for you,’ Rose told her firmly. ‘You’d only be in the way. Much better stay here until sent for.’ She saw it was an answer that comforted them, and headed for the door, shrugging them off with relief.

But Alice stopped her as she opened it with another question. ‘Where is he?’

‘In the small dining-room,’ she answered reluctantly. She did not want to get involved with the details. Folsham the undertaker had brought a temporary coffin with him, not having anything grand enough for the earl until it was made specially, and it was positioned on the dining-table, a purple cloth under it and another over. Folsham had brought those, too. There it stood while decisions were made.

Alice said, ‘Can we see him?’

The question surprised a sharp answer out of Rose. ‘Of course not. The very idea!’ She regarded them, sitting, backs straight and hands in laps as they’d been taught, looking very forlorn. Her lips tightened. They were not her responsibility. She had enough to do without that. ‘I’ll get one of the girls to bring up some coal,’ she said. And went out.

Giles Tallant, Viscount Ayton, had stepped out of the tent for a moment to stretch his neck, and stood under the canopy, surveying the scene. Gold and blue was the palette, the gold of the sand and the blue of the sky. Like an heraldic achievement, he was thinking, azure and or with lesser dabs of white, grey and brown, when the message was brought to him.

It was misspelled as usual, written down by someone whose first language was not English – and who probably rarely wrote things down even in his own language – but the meaning was unequivocal. Your father is dead. Come home at once.

Shock rolled through him at the stark words. His mother, of course, would not waste money on a gentler phrasing – and, besides, as she never spared herself, why should she spare anyone else? Shock, followed by … He would not allow himself to feel anger, which would be inappropriate, but his anguish at this news was at least in part made up of frustration. He had known all his life, of course, that this day would come, and the awareness had been a brooding shadow in a corner of his mind. But his father had been a fit and healthy man, and Ayton had hoped to have many more years of freedom. It must have been an accident, he supposed: illness would have been longer foretold. Father, dead! Inwardly, he damned the Fates that had allowed it to happen. Outwardly, he turned his face up to the sky and closed his eyes, looking like a man struggling with sorrow.

He felt the dry heat of the sun beat on his eyelids, felt the prickle of sand on his skin, heard the background sounds of the workings – the susurrus of shovels in sand, the ring of metal on stone, the grumbling groan of a camel, the creak of wooden poles and canvas as the sunshades worked in the occasional breeze. This was his world, the clean dryness of the desert and the constant undercurrent of excitement about what might be discovered. He did not want to go home. He thought of the grey wetness of England, the sameness of day-to-day, the stultifying rules and immutable traditions, the confinement and responsibility that awaited him. He did not want to be earl. He did not want to go home!

He had never got on with his father. They were too different. The earl had quite liked his younger brother Richard, though he cost him money and embarrassment. Had Ayton been sacked from Eton for misconduct, had he spent his time at university drinking and girling, his father would have roared at him, but it would have been a roar that rose from a depth of understanding, even affection. Had Ayton been an idler, an expensive wastrel, running up debts, chased for unpaid bills by tailors and wine merchants, his father would have punished him and loved him.

But he had spent his time at Eton studying, then insisted on going to University College London, to study under Flinders Petrie, rather than to Oxford as a Tallant should. He had won that great Egyptologist’s approval for his application and his methodical habits, and had gone on his first expedition at only nineteen, when Petrie had recommended him to Percy Newberry, who took him to the excavation of el-Bersheh. The fever had entered his blood. It was all he wanted to do. He had taken his degree – which was, if not disreputable, at least odd – and afterwards hoped to apply his knowledge in the field for as long as his cadethood lasted.

Stainton could not understand it. It was not what his heir should do. It was not right. It was not done. He had raged and blustered, tried at first to forbid him, but Ayton was of age and could defy him. He could not even cut him off, because the cadet title came with an independent income – not large, but enough for a young man with modest tastes and no desire to gamble and carouse. Abroad, he spent little. And archaeological expeditions were, in any case, paid for by rich families like the Stanhopes and the Cecils, or by associations like the Egypt Exploration Society. Ayton mixed, both in England and on the Nile, with titled men of good family, which made the earl roar all the more, baffled, because he could not put his finger on why it was wrong. He just knew it would not do. So Ayton kept away as much as possible, and when he had to be in England, he stayed with friends, or in the cheap lodgings in London he kept up. He visited Ashmore Castle as little as possible.

I am not ready for this, Ayton thought. The Ca

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...