- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

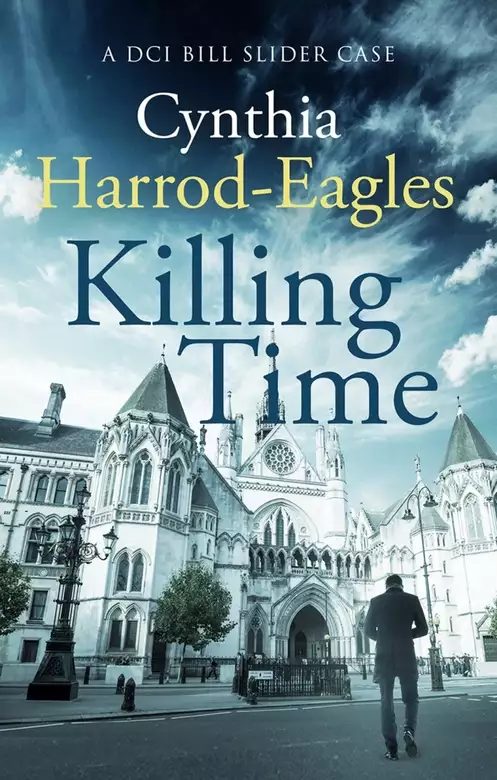

Synopsis

'An outstanding series' NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

A Bill Slider Mystery

Detective Inspector Bill Slider is back at work with a thumping headache, courtesy of the last villain he apprehended. But he is minus Atherton, a friend and colleague, who's still recovering from his injuries.

Slider was hoping for a quiet week, but a murder at a night club plunges him into the underworld of entertainment to question table-dancers, prostitutes, pimps and cabinet ministers. And when it appears that this murder could be linked to another unsolved case, Slider is left with more questions than ever.

What with Atherton's slow recovery and his replacement's unhealthy interest in Slider, the DI has enough to fuel his headache for the foreseeable future. But the old grey matter won't be denied; doggedly and with a whimper, Slider starts to unravel the truth...

Praise for the Bill Slider series:

'Slider and his creator are real discoveries'

Daily Mail

'Sharp, witty and well-plotted'

Times

'Harrod-Eagles and her detective hero form a class act. The style is fast, funny and furious - the plotting crisply devious'

Irish Times

Release date: September 1, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 224

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Killing Time

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

‘Bill!’

Slider stopped and turned. ‘Hello, Ron.’

‘I didn’t know you were back.’ Carver looked him over keenly. ‘Shouldn’t you still be on sick-leave? You look terrible.’

‘Thanks,’ Slider said. ‘I feel a bit under the weather, but Honeyman asked me to come in. We’re short-handed, with Atherton

in the cot.’

‘How is he?’ Carver’s face pursed with a moment’s sympathy.

‘Still very poorly.’ Slider marvelled for a moment at the word. It was how the hospital had described him yesterday. They

had a box of these strange shorthand terms for the varying degrees of human distress – critical, comfortable, stable, poorly

– which they used like flashcards. It was kinder than describing reality. Reality was Atherton with a hole in him; Atherton

a white face and fragile blue eyelids above a sheet, drips and drains and bags, and a cradle to keep the bedclothes off the

wound, so that he looked like Tutankhamun without the gilding.

It was hard to think of clearing up the Gilbert case as a success, though Gilbert was under wraps and the CPS was as chuffed

about it as the CPS ever was about anything. But Slider had stupidly allowed himself to be ambushed by Gilbert, coshed, trussed

up and, for a harrowing period, kept prisoner and threatened with a knife. When Atherton had come looking for him, Gilbert

had jumped him, and the same knife had ended up where Atherton normally kept quenelles de veau or designer sausages with red onion marmalade. Slider had narrowly escaped a fractured skull, but Atherton had nearly died, and was not out of the woods yet.

‘You’ve been to see him?’ Carver asked.

‘More tubes through him than King’s Cross,’ Slider said.

‘It’s a bastard,’ Carver said in omnibus disapprobation. ‘He’ll be off a while then.’

It was not a question. Slider shifted uncomfortably away from the subject, and said instead, ‘I hear Mills is leaving the

Job?’ DS Mills, alias Dark Satanic, an old colleague of Slider’s, had been a suspect for a time in the Gilbert case.

‘Yeah. Well, I can’t blame him. It’d be tough after what he’s been through. But I’d only just got the extra manpower,’ he

complained. ‘I don’t suppose Honeyman’ll roll for it again – not with you being short.’ He gave Slider a resentful stare as

if it was his fault.

‘Where’s he going?’

‘What, Mills? Wales, I gather. What’s that place he went on holiday every year?’

‘Rhyl?’

‘That’s it. This bloke he met there, owns his own business, offered Mills a billet. Salesman. Computerised security systems.

Thought it’d be a boost to have an ex-dick toting the brochures round.’

Poor old Dark Satanic, Slider thought. Going on the knocker was a bit of a come-down from the CID. Or was it? ‘I suppose it’s

a job,’ he said doubtfully.

‘I don’t think he minds,’ Carver shrugged. ‘I think he wants to see a bit of life before it’s too late.’

‘In Wales?’

‘He’s taking his mum with him,’ Carver said – one of his better non-sequiturs. ‘I dunno but what he hasn’t got the right idea,’

he went on, his face settling into familiar creases of gloom. ‘The Job’s changing, Bill. Every day coppers are getting shot

and knifed, bashed on the head and dumped, and for what? We work our balls off catching the villains, and the courts let ’em

off with a slap on the wrist, because some social worker says they had a rotten mum and a no-good dad. Yeah, but if one of

us makes some pissy little mistake in procedure, it’s wrongful arrest and the tabloids start screaming about fit-ups. It makes

you wonder why you go on.’

Slider, accustomed to Carver’s style, deduced his heart was not bleeding for Slider’s bashed head or Atherton’s knifed stomach.

‘Has someone else got hurt, then?’

‘You haven’t heard about Andy Cosgrove?’

‘No. What about him?’ Cosgrove was the very popular ‘community beat’ copper for the White City Estate, a PC of the Neo-Dixon

school, calm, authoritative, patient, knowledgeable; worth his considerable weight in gold to the Department for the background

information he could give on any case arising on his beat.

‘He was attacked last night. Beaten up and left for dead.’

‘Shit,’ Slider said, appalled. ‘How is he?’

‘Not too clever. He’s in a coma, on life-support in St Stephen’s.’

‘Who did it? What have you got?’

‘Sod all,’ Carver grunted. ‘He was found on that piece of waste ground round the back of the railway arches down the end of

Sulgrave Road, but that’s not where it happened. He got smacked somewhere else, driven there and dumped.’

‘Professional? What was he working on?’

‘Nothing in particular – nothing I know about, anyway. Just routine stuff. Like I said, there’s nothing to go on.’ He was

silent a moment, sucking his upper lip. He’d had a moustache once that he used to suck, and though he’d shaved it off ten

years ago, the habit remained. A bloke and his face-fur, Slider reflected, could be as close as man and wife. ‘Honeyman’s

shitting himself. It was the last straw for him,’ Carver went on. ‘You going to see him? Reporting back?’

‘That’s where I was heading.’

‘He’s like a flea in a frying pan. Wants a bodyguard to cross the parking lot.’

I don’t blame him, Slider thought when he left Carver. Honeyman was only a temp in the post of Detective Superintendent, having

been put in as a night watchman when the last Det Sup had died at the crease. Recent events were enough to make anyone nervous,

but Honeyman was only a few months short of his pension, and sudden death or grave injury could seriously upset a man’s retirement

plans.

Through the open door Slider could see Honeyman at his desk, writing. Slider tapped politely and noted how the little chap started. ‘Oh, Slider – come in, come in. Good to see you back.’ Honeyman stood and came round the desk and held out his

hand, all evidence of unusual emotion. Slider stood patiently while Honeyman looked him up and down – mostly up, because Eric

Honeyman was built on a daintier scale than most policemen. ‘And how are you feeling now? Quite recovered? I must say we can

use you. We seem to be terribly accident-prone recently. You’ve heard about Cosgrove?’

‘Yes sir, just this minute.’

‘Terrible business.’ Honeyman shook his head hopelessly.

‘Ron Carver’s firm is on it, I gather.’

‘Yes,’ Honeyman said, rather absently. He seemed to be hesitating on the brink of a confidence. ‘I’ve not been feeling quite

on top form myself, lately.’ Slider made a sympathetic noise. ‘The fact is,’ Honeyman plunged, ‘I’ve asked to have my retirement

brought forward. On medical grounds.’ His eyes flickered guiltily to Slider and away again. ‘This sort of thing – involving

your own men – it takes it out of you. I suppose that must sound to you—’

‘You’ve done your time, sir,’ Slider filled in obligingly.

‘Nearly thirty years,’ Honeyman agreed eagerly. ‘It was so different when I joined the service. Policemen were respected.

Even the villains called you “sir”. Now you have respectable, middle-class people calling you “pig”. And breaking the law

so casually, as if it was just a matter of personal choice.’

Slider had no wish to stroll down this lane in this company. ‘Have you got a date for leaving, sir?’

‘The end of next week. I haven’t announced it yet, but I asked them to relieve me as soon as they could find a replacement.’

Honeyman chatted a bit, something about his retirement plans and his wife, and Slider drifted off. A silence roused him, and

coming to guiltily he asked, ‘Is this still confidential, sir? About you going?’

‘I don’t see any reason to keep it a secret. No, I shall send round a memo later today, but you can spread the word to the

troops, if you like.’

Start the collection for my leaving present, Slider translated.

‘Very well, sir.’

McLaren was at his desk, eating a fried egg sandwich from Sid’s coffee-stall at the end of Shepherd’s Bush Market. Slider knew that was where it came from, because it was the only place

nearby you could get them with the yolk in the correctly runny state. You had to be in the right mood to be on either side

of a fried egg sandwich, Slider thought. It helped also not to be just out of hospital after a whack on the head.

‘Hello, guv,’ McLaren said indistinctly. ‘I didn’t know you were back. You’re looking double well.’

‘For Chrissake, McLaren, not over your reports,’ Slider said.

McLaren swivelled in his chair and dripped over his waste paper basket instead.

‘How’re you feeling, boss?’ Mackay came forward, tin tray in hand. ‘Can I get you a coffee?’

Slider sat down on the nearest desk – Atherton’s, as it happened. ‘A few days away, and I’m forgotten. You know I don’t drink

instant.’

‘Tea, I meant,’ Mackay said hastily.

‘Thanks. No sugar, in case you’ve forgotten that as well.’

Mackay apologised in kind. ‘We’ve got some doughnuts.’

‘From Sid’s? Now you’re talking.’

His eye found a stranger, a tall man in his late thirties, with sparse, sandy hair, plentiful freckles, and that thick, pale

skin that went with them. He wore large gold-rimmed glasses and a bristly moustache, and he gangled forwards, slightly drooping,

with an air of practised melancholy, as though expecting to be ridiculed.

‘We haven’t met, guv. I’m your new DS,’ he said, holding out his hand. He had a strange, semi-castrato, counter-tenor voice

and a Mancunian accent. His eyes behind the glass were bulgingly soft, greyish-green like part-cooked gooseberries, but held

a gleam of humour. With a voice like that, you had to have a sense of humour to survive.

‘Ah, yes, Beevers’ replacement,’ Slider said. ‘You came last week, didn’t you?’

‘That’s right. Colin Hollis,’ he offered. Slider immediately felt more comfortable. A CID department without a Colin in it

never seemed quite natural, somehow. ‘From Manchester Stolen Cars Squad.’

‘Ah. This’ll seem like a bit of a holiday for you, then,’ Slider said.

‘Talking of holidays.’ Anderson sidled up, a menacing photo-envelope in his hand. ‘Would you like to see these, guv? My loft

conversion. I’ve done a lot while you’ve been away.’

This was Anderson’s latest project – a Useful Games Room Stroke Extra Bedroom. He had decided, unsurprisingly, to line the

whole room with pine stripping. ‘I’ve got before and after shots,’ he added beguilingly.

Slider was deeply grateful to be interrupted by the arrival of WDC ‘Norma’ Swilley. Tall, athletic, blonde, gorgeous, and

yet with a strangely unmemorable set of features, small-nosed and large-mouthed in the manner of a Baywatch Beauty, she was,

according to Atherton, the living proof that Barbie and Ken had sex. She was a good policeman, but she had a low fool-suffering

threshold – which probably accounted for why she was still a DC – and she swept Anderson aside with the authority of a staff

nurse.

‘The boss doesn’t want to see those. How are you, guv? And how’s Jim? All we get is the official report.’

‘Progressing slowly. I saw him yesterday. He’s sleeping a lot of the time, though.’

‘Drugged, I suppose. It must still be pretty painful.’

Slider nodded. ‘Haven’t you seen him?’

‘Just once. They’re restricting visitors. I suppose you know that. Just one from the firm, they said, so I tossed Mackay for

it.’

‘Doesn’t he wish,’ McLaren muttered.

‘Of all people,’ Norma said, ignoring him, ‘for Jim Atherton to get it in the stomach!’

Slider nodded. He’d thought of that. ‘It’s like a pianist getting his fingers broken.’

‘Him and food,’ Norma said, ‘it’s one of the great love affairs. Paris and Helen, Antony and Cleopatra—’

‘Marks and Spencer?’ Anderson suggested absently.

McLaren licked the last of the yolk and grease from his fingers. ‘They say he’s not coming back. Lost his bottle.’

‘You’ve got the most hyperactive They I’ve ever come across,’ Slider said. ‘All I know is he’s still very sick and he’ll be in hospital a while yet, and after

that he’ll have to convalesce. We’re going to be without him a good few weeks. What he’ll decide after that no-one knows –

least of all him, I should think.’

There was a buzz of conversation about what Atherton might or might not be feeling, and to break it up, Slider told them about

Honeyman leaving. The news was met with a storm of equanimity.

‘I know he hasn’t been with us long,’ Slider concluded, ‘but I think we ought to organise a whip-round. At least buy him a

book or something. And a card. Get everyone to sign it.’

‘I’ll do it,’ McLaren offered, preparing to engage a doughnut in mortal combat.

‘Fair enough,’ Slider said doubtfully. ‘But try not to get fingermarks on it.’

McLaren looked wounded. ‘I won’t let you down, guv.’

‘There’s no way you can,’ Slider assured him.

He had lunch in the canteen. Chicken curry, which they made halfway decently except that they would put sultanas in it which

to his mind belonged in pudding not dinner, and raspberries with crème aux fraises, which was cateringspeak for pink blancmange. Slider didn’t mind because he actually liked blancmange. He was spooning it

up when a shadow fell over him and he looked up to see Sergeant Nicholls bearing a tray. Nicholls’ handsome face lit in a

flattering smile. ‘You’re back. That was quick.’

‘Honeyman begged me. I couldn’t stand seeing a strong man weep, so—’ He shrugged.

Nicholls obeyed his tacit invitation to sit down. ‘But are you able for it?’ he asked, unloading his tray.

‘Such tender concern. Yes, thanks. I still get the odd headache, but on the whole I’d sooner be working. Takes the mind off.’

‘Bad dreams?’ Nicholls asked perceptively. ‘Yes, I’m not surprised. It has to come out somewhere after a shock like that.

But I’d feel the same in your shoes: get back on the horse as soon as possible.’ He reached over the table and laid a hand

on Slider’s forearm. ‘Gilbert’s banged up tight as a trull,’ he said, ‘and there’s enough evidence to send him down for ever.

He’s not getting out, Bill. Keep that in mind.’

‘Thanks, Nutty.’ They had a bit of a manly cough and shuffle. ‘I expect I’ll be kept busy, anyway, being two men down.’

‘Och, well, I’ve some better news for you on that front,’ Nicholls said. ‘They’re sending you a DC as a temporary replacement for Atherton. Someone called Tony Hart, from Lambeth. D’ye know him?’

‘Never met him,’ Slider shook his head. ‘Ah well, that’s better than nothing. But I wonder Honeyman didn’t tell me. I was

in there this morning.’

‘Honeyman’d mebbe not know yet. He hasn’t got my sources. Did you know he was leaving next week?’

‘Yes, he told me that.’

‘I shall miss him, in a way, you know,’ Nutty said, thoughtfully loading his fork with Pasta Bake. ‘He’s a real lady.’

Colin Hollis stuck his head round Slider’s door. ‘There’s some bloke downstairs asking for you, guv. Won’t take no.’

‘Won’t what?’

Hollis inserted his body after his head. ‘Well, I say bloke. Bit of a debatable point, now I’ve had a look at him. Ey, guv,

if a bloke wears woman’s underwear, is that what you’d call a Freudian slip?’

‘Wipe the foam from your chin and start again,’ Slider suggested.

‘Bloke,’ Hollis said helpfully. ‘Come in asking for you, so I went down to see what he wanted, but he says he knows you, and

you’re the only one he can talk to now that PC Cosgrove is gone.’ He eyed Slider with undisguised interest.

‘What does he want?’

‘He wouldn’t say. But he’s nervous as hell. Maybe he’s got some gen on the Cosgrove case.’

‘Name?’

‘Paloma. Jay Paloma.’ Hollis gave an indescribable grimace. ‘I bet that’s not his real name, though. Una Paloma Blanca – what’s

that song? D’you know him, guv?’

Slider frowned a moment, and then placed him. ‘Not really. I know his flatmate, Busty Parnell.’ He sighed. ‘I suppose I’d

better come.’

Hollis followed him through the CID room. ‘He’s got some gear on him. Making a bit, one way or the other. Probably the other.

Funny old world, en’t it, guv, when the Game makes more than the Job?’

Slider paused at the door. ‘Every man makes his choice.’

‘Oh, I’ve no regrets,’ Hollis said, stroking his terrible moustache. ‘I’d bend over backwards to help my fellow man.’

Slider trudged downstairs, feeling a little comforted. It was early days yet, but it looked as though Hollis was going to

be an asset to the Department.

Slider had become acquainted with Busty Parnell in his Central days. She described herself as a show dancer, and indeed she

wasn’t a bad hoofer, but a small but insidious snow habit had led her into trouble, and she had slipped down the social scale

to stripper and part-time prostitute. Slider had busted her once or twice and helped her out on other occasions, when a customer

turned nasty or a boss was bothering her. Sometimes she had given him a spot of good information, and in return he had turned

a blind eye to a spot of victimless crime on her part. And sometimes, in the lonely dogwatches which are so hard on the unmarried

copper, he had taken a cup of tea with her at her flat and discussed business in general and the world in particular. She

had made it plain that she would be glad to offer him more substantial comforts, but Slider had never been one to mix business

with pleasure. Besides, he knew enough about Busty’s body and far too much about her past life to find her tempting.

Her name was Valerie, but she had always been referred to as Busty in showbiz circles to distinguish her from the other Val

Parnell, the impresario, for whom she had once auditioned. Slider had lost sight of her when he left Central, but she had

turned up again a year or so ago on the White City Estate, sharing a flat with Jay Paloma. The last Slider had heard Busty

had given up the stage and was working as a barmaid at a pub, The British Queen. Her flatmate was employed as an ‘artiste’

at the Pomona Club, a rather dubious night club whose advertised ‘cabaret’ consisted mainly of striptease and simulated sex

acts, and which distributed more drugs than the all-night pharmacy in Shaftesbury Avenue.

Jay Paloma was waiting for Slider in one of the interview rooms. He was beautifully, not to say androgynously, dressed in

a white silk shirt with cossack sleeves, and loose beige flannel slacks tucked into chocolate-coloured suede ankle boots,

with a matching beige jacket hanging casually over his shoulders. There was a heavy gold chain round his throat, a gold lapel pin in the shape of a treble clef on the jacket, and discreet

gold studs in his ears. A handbag and nail polish would have tilted the ensemble irrevocably over the gender balance point;

as it was, a casual glance suggested artistic rather than transvestite.

Jay Paloma was tall and slenderly built, and sat with the disjointed grace of a dancer, his heels together and his knees fallen

apart, his arms resting on his thighs and his hands dangling, loosely clasped, between them. The hands were well-kept, with

short nails and no rings. His thick, streaked-blond hair was cut short, full and spiky like a model’s; his face was long and

large-nosed, and given the dark eyeliner on the underlids and his way of tilting his face down and looking up under his eyebrows,

he bore an uncanny resemblance to Princess Di, which Slider supposed was purely intentional.

He was a very nervous, tremulous Princess Di today, quivering of lip and brimming of eye. He started to his feet as Slider

came in, thought about shaking hands, fidgeted, looked this way and that; and obeyed Slider’s injunction to sit down again

with a boneless, graceful collapse. He put a thumb to his mouth and gnawed the side of it – not the nail or even the cuticle

but the loose flesh of the first joint. Probably he had been a nail-biter and had cured himself that way. Nails would be important

to him; appearance important generally. Given that he shared an unglamorous flat with Busty and worked at the Pomona, his

expensive outfit suggested that he exploited his body in a more lucrative way out of club hours.

‘So what can I do for you?’ Slider asked, pulling out a chair and sitting facing him. ‘Jay, isn’t it? Do I call you Jay?’

‘It’s my professional name,’ he said. He had a soft, husky voice with the expected slightly camp intonation. It was funny,

Slider reflected from his experience, how many performers adopted it, even if they weren’t TWI. It was a great class-leveller.

It was hard to guess his origins – or, indeed, his age. Slider would have put him at thirty-five, but he looked superficially

much younger and could have been quite a bit older. He had makeup on, Slider saw: foundation, mascara and probably blusher,

but discreetly done. It was only the angle of the light throwing into relief the fine stubble coming through the foundation

that gave it away.

‘It’s nice of you to see me,’ Jay said, with the obligatory upward intonation at the end of the sentence; the phantom question mark which had haunted Estuary English ever since Australian

soaps took over from the home-grown variety. It made it sound as though he wasn’t sure that it was nice, and gave Slider the

spurious feeling of having a hidden agenda, of being persecutor to Jay’s victim.

‘Any friend of Busty’s is a friend of mine,’ he said. ‘How do you come to know her, by the way?’

‘Val and me go way back. We were in a show together – do you remember Hanging Out in the Jungle? That musical about the ENSA troupe?’

‘Yes, of course I do. It caused quite a stir at the time.’

Slider remembered it very well. It had hit the headlines not only because it was high camp – still daring in those days –

and full of suggestive jokes; not only because of the implication, offensive to some, that ENSA had been riddled with homosexuality;

but because before Hanging Out, the star, Jeremy Haviland – who had also directed and part-written the show – had been a respected, heavyweight actor of

Shakespearian gravitas. Seeing him frolicking so incongruously in satin frocks and outrageous makeup had been one of the main

draws which kept packing them in through its short but momentous run. But the gradually-emerging realisation that Haviland

had merely type-cast himself had caused secondary shock-waves which had destroyed his career. This was some years before homosexuality

had become popular and acceptable. Six months after Hanging Out closed, Haviland committed suicide.

‘Val was in the chorus, singing and dancing, but I had a proper part,’ Jay went on. ‘It was a terrific break for me.’

‘Which were you?’

‘I played Lance Corporal Fender – the shy young lad who had to play all the young girls’ parts, and got all those parcels

of knitted things from his mother?’

‘Yes, I remember. You did that song with Jeremy Haviland, the Beverley Sisters number, what was it?’

‘“Sisters, sisters, there were never such devoted sisters”,’ Jay Paloma sang obediently, in a sweet, husky voice. ‘It was

Jeremy got me the part. I really could dance – I’d been to a stage-and-dance school and everything – but all I’d done before

was a student review at UCL. I was sharing a flat at the time with the president of Dramsoc, and he wangled me into it, because frankly, none of the rest of them could sing or

dance worth spit. Anyway, Jeremy saw me in it, liked me, and took a chance. He was so kind to me! I owed him everything. I

got fave reviews for Hanging Out and everyone reckoned I was headed for stardom. But then all the fuss broke out over poor Jeremy, and the show folded, and

we were all sort of dragged down with him. Tarnished with the same brush, you might say. It was hard for any of us to get

work after that, and, well, Jeremy and I had been – you know—’

‘Close,’ Slider suggested.

Jay seemed grateful for the tact. ‘He tried to help me, but everyone was avoiding him. And then he—’ He gulped and made a

terminal gesture with both hands. ‘It was terrible. He was such a kind, kind man.’

‘I didn’t know Busty was in that show. It must have been before I met her.’

‘She and I shared lodgings. She was like a big sister to me.’

‘She was at the Windmill when I first knew her.’

‘Yes, that’s where she went when Hanging Out closed. It was always easier for women dancers to get work. Well, we sort of lost sight of each other for a long time. And

then about eighteen months ago we bumped into each other again in Earl’s Court.’

By then both had drifted down out of the realms of legitimate theatre and into the shadowy fringe world where entertainment

and sex were more or less synonymous. Busty was doing a bit of this and a bit of that – stripping, promotional work, topless

waitressing. Jay was dancing when he could get it, filling in with drag routines, modelling, and working for a gay escort

agency.

‘Val was doing the Motor Show – dressed in a flesh suit handing out leaflets about some new sports car. She was supposed to

be Eve in the Garden of Eden, the leaflets were apple-shaped. The car was the New Temptation – d’you get it?’ He sniffed derisively.

‘She hated promo work – we all do. Being a Sunflower Girl or a Fiat Bunny or whatever. Humiliating. And the hours are shocking

and the pay’s peanuts, unless you sleep with the agent, which you often have to to get the job at all. Well, you have to take

what you can get. And we’re neither of us teenagers any more. There just isn’t the work for troupers like us. Everyone specialises,

and the kids coming out of the dancing schools now can do things – well, they’re more like acrobats to my mind. It’s not what I’d call dancing.’

‘And what about you? What were you doing?’

‘I had a spot at a night club in Earl’s Court – a sort of striptease.’

Slider had a fair idea which club. ‘Striptease?’

Jay Paloma looked haughty. ‘It wasn’t what you think. In fact, it was my best gig after Hanging Out closed. I came on in this evening gown and white fur and diamonds and everything, and did this wonderful routine. Like Gypsy

Rose Lee, you know – all I ever took off was the long gloves. Absolutely classical. It brought the house down! Well, anyway,

Val and I bumped into each other in the street, and we were so glad to see each other, we decided to share again. We had this

place in Warwick Road to start with, and then we moved out here.’

Fascinating though this was, Slider had a lot to do. ‘So what did you want to talk to me about?’ he asked, with a suggestion

of glancing at his wrist.

Jay hesitated. ‘I say, look, d’you mind if I smoke?’

‘Go ahead.’ Paloma reached for the pocket of the jacket. The cigarettes were in their original packet, but the lighter looked

expensive, a gold Dunhill, Slider thought. ‘It always amazes me,’ he added as he watched the lighting-up process, ‘how many

of you dancers smoke. I’d have though. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...