- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

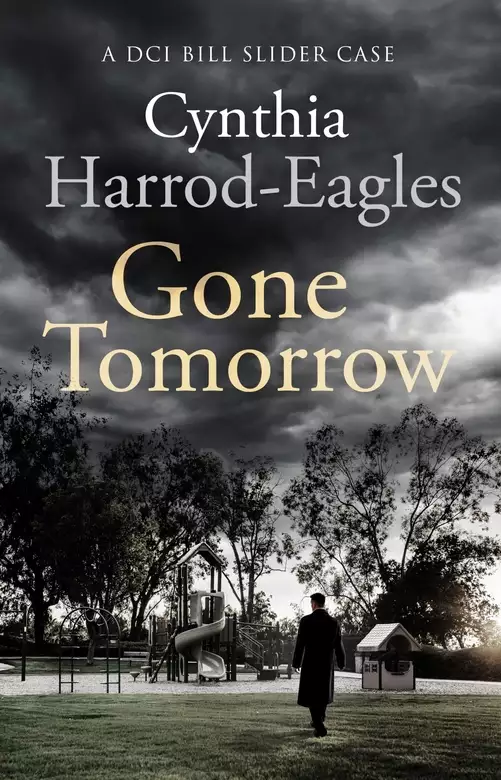

Synopsis

'An outstanding series' NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

A Bill Slider Mystery

The stabbed body of a well-dressed man is found slumped on a swing in a children's playground in the heart of Detective Inspector Bill Slider's patch.

From the seedy pubs of Shepherd's Bush through the brothels of Notting Hill to the mansions of Holland Park, Slider and his team unearth the victims' sordid lifestyle of debts, drugs and dodgy deals. It soon becomes clear that their prime suspect is a crime baron who will stop at nothing to keep his identity hidden.

However, Slider is not only up against a resourceful villain, but is also fighting to stop the case being taken off his hand. He's so busy he hasn't a spare moment. But when the case is all over, he'll finally have the time to hear what his on-off girlfriend has been trying to tell him...

Praise for the Bill Slider series:

'Slider and his creator are real discoveries'

Daily Mail

'Sharp, witty and well-plotted'

Times

'Harrod-Eagles and her detective hero form a class act. The style is fast, funny and furious - the plotting crisply devious'

Irish Times

Release date: September 1, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Gone Tomorrow

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

Detective Sergeant Hollis held his car door open for him.

‘You’re very kind,’ said Slider, climbing out.

‘I used to get hit if I wasn’t,’ Hollis said. He was a scanty-haired beanpole of a Mancunian with a laconical delivery.

‘Atherton not in yet?’ DS Atherton, Slider’s bagman, was due back from holiday that morning.

‘Not when I left.’

Slider nodded towards the screens. ‘Who is it?’

‘Dunno, guv. He’s not saying much. Large bloke, no ID. I don’t recognise him.’

‘Who found him?’

‘Parkie. He doesn’t know him either.’

Hammersmith Park was a long, narrow piece of land which lay between the White City estate and Shepherd’s Bush. It had a gate at either end. One was in South Africa Road – home to the stadium of Queen’s Park Rangers football team, known locally, for their horizontally striped shirts, as ve ’oops (or, if they had been having a successful run, superoops). The other gate was in Frithville Gardens, a cul-de-sac turning off the main Uxbridge Road which also led to the back door of the BBC Television Centre. Between the two lay the moderately landscaped green space of lawns and trees, with a sinuous path from gate to gate which was used as a cut-through for estate dwellers to and from the Bush.

Slider had been called to the South Africa Road gate. Just inside it, to the left, was a children’s playground, whose amenity had been much reduced over the years in the retreat before vandalism. There was a paddling pool with no water, a sandpit with no sand, two rocking horses which, in the interests of safety, had been bolted to the ground and no longer rocked, and two sets of swings, one for babies and one for children.

Between the playground and the road was a small two-storey building which had once been an office and residence for a park keeper. It was now unused and all its orifices had been sealed up with breeze-block – the only way these days to keep out vandals, who had the tenacity of termites and would set fire to their own left legs in pursuit of a thrill. The only purpose of the building now, Slider noted a little glumly, seemed to be to conceal activity in the playground from anyone passing by in the street.

The body was on one of the children’s swings. Slider passed through the screens to take a look. The swings were of a simple, municipally sturdy design, suspended from a framework made of scaffolding poles by chains thick and heavy enough to have towed a ship. The seats were made from short, thick chunks of wood that might have been chopped from railway sleepers, and the one was bolted to the other with sufficient determination to have resisted mindless destruction.

Deceased was seated, slumped forward, head and arms hanging, legs bent back and feet resting pigeon-toed on the ground. He had been a large, muscular man, otherwise he would probably have slipped off; as it was, he was kept in place by his own weight pressing against the chains, the bulge of the deltoids to one side and the pectorals to the other making a sort of channel for each chain to lie in snugly.

Hollis ranged up silently beside Slider.

‘When was he found?’ Slider asked.

‘Park keeper came to open up at half seven. The gates are open between seven-thirty in the morning and dusk,’ he added, anticipating Slider’s question. ‘Dusk is a bit of a movable feast, o’ course. Sunset’s around nine o’clock, give or take, this time o’ year. But in practice the parkie shuts up when he feels like it, or when he remembers.’

Slider grunted, staring at the body. It was a fit-looking man, probably in his thirties, dressed in an expensive leather blouson-type jacket and a thin black roll-neck tucked into tight blue jeans, Italian leather casuals and a gold chain round his neck.

‘The Milk Tray man’s uniform,’ Slider commented.

‘He looks like an up-market bouncer,’ Hollis agreed.

The hair was light brown and cut very short, the face was Torremolinos tanned, and he had a gold earring in the top of his left ear, small and quite discreet, the sort that said okay, I’m cool, but I’m also tough.

It was strangely hard to tell with corpses, when the face was without expression and the eyes closed, but this man probably would have been quite good-looking in life, of the sort a certain kind of woman fell for. Only his hands let him down: they were ugly, with badly bitten nails and deep nicotine stains. He wore a heavy gold signet ring, unengraved, on the middle finger of the right hand – the place fighters wore it, where it would do most damage.

Hollis reached out with a Biro and delicately lifted aside one side of the jacket to show Slider the stab wound below the left breast. ‘Single blow, right where he lived. The only one as far as I can see, without moving him.’

‘Not much staining,’ Slider said. There was a stiff little patch around the wound, but nothing had gushed or dripped. ‘Probably killed him instantly. If the heart had gone on pumping for any length of time there’d’ve been a lot more blood.’

‘That’s what I thought. Professional?’ Hollis suggested.

Slider did not commit himself. ‘No sign of the weapon?’

‘Not so far.’

‘And no ID?’

‘Nothing in the jacket or the back trouser pocket. I’ve not gone in the front trouser pockets, o’ course, but they feel empty.’

‘Those jeans are so tight there can’t be room down there for much more than his giblets,’ Slider observed.

‘Anyroad, all I found was money and fags.’

‘Oh well, there might be something more when we can strip him off. Doctor been yet?’

‘No, guv. Held up in traffic.’

Slider stepped back out to look around. What had brought this man here to his death? A meeting? Or perhaps he had been killed elsewhere and left here on the swing as a nasty kind of joke? At all events, it was a fairly private place, hidden from the road by the bulk of the defunct building. The park was overlooked only from the right-hand side by the upper floors of the flats in Batman Close, and then only in winter. At this time of year the foliage on the well-grown trees baffled any view of the ground. Yes, provided a person could get into the park in the first place without attracting attention, the spot was well chosen.

Beyond the park railings a small murmuring crowd had now collected, the usual mix of the idle, the elderly, and truanting kids. Slider scanned them automatically, but he didn’t recognise anyone except Blind Bernie and Mad Sam, a well-known couple round the Bush. Mad Sam was Blind Bernie’s son, and was not mad, only mentally retarded, a round-faced, smiling child of forty. He was Bernie’s guide, and Bernie looked after him. They each kept the other out of A Home, the thing both dreaded with Victorian horror. Slider could see Sam’s lips moving as he told Bernie what he could see, and Bernie’s as he translated what Sam told him. Now he came to think of it, they lived in Frithville Gardens, so they naturally would be interested in something that happened in what was virtually their front garden.

Along the roof of the disused keeper’s house a row of seagulls sat, shuffling their wings in the small breeze and turning their heads back and forth to see if all the unusual activity portended food. Once, they had come up into the estate from the Thames only in bad weather, to shelter, but now they seemed to live here all the time. Probably the large area of high buildings reminded them of cliffs; and there was plenty of rubbish for them to pick over. They had forgotten the sea; but on a quiet day their raucous squabbling cries brought it near in Slider’s mind.

It was quiet here today, with the road temporarily closed to traffic. Somewhere out of sight a car horn broke the gentle background wash of distant city sounds, a composite murmur like the ‘white noise’ of silence; a crow cawed in one of the park trees, a fork-lift truck whined briefly behind the wall of the TVC, and far above a jumbo growled its way to Heathrow, flashing back the sun as it crawled between clouds.

All around, for miles and miles in every direction, in streets and shops and houses, real life was going on, oblivious; but here a dead man sat, the full stop at the end of his own sentence, with a little still pocket of attention focused fiercely and minutely on him. Why him? And why here? Slider felt the questions attaching themselves to him like shackles, chaining him to this scene, to a well-known process of effort, worry and responsibility.

He had a moment’s revulsion for it all, for the blank stupidity of death, and longed to be anywhere but here, and to have any job but this. And then the doctor and the meat wagon arrived simultaneously, one of the uniforms asked him about press access, the police photographer came to him for instructions, and one of his own DCs, Mackay, turned up with the firm’s Polaroid. Extraneous feelings fled as the job in hand claimed him, with a familiarity, at least, that was comfortable.

Detective Superintendent Fred ‘The Syrup’ Porson looked exhausted. He’d had this nasty ‘summer flu’ that was going around – seemed to have been having it for months – and his face looked grey and chipped. The rosy tint to his pouched eyes and abraded beak was the only touch of colour in the granite façade.

The HAT car (Homicide Advice Team) had been and gone, assessing the murder.

‘We’re keeping it,’ Porson told Slider.

‘The playground murder?’

‘What did you think I meant?’ Porson snapped irritably. ‘Queen Victoria’s birthday? And you don’t know it’s a murder yet.’

‘Single stab wound to the heart and no weapon on the scene,’ Slider mentioned.

‘When you’ve been in the Job as long as I have, you’ll take nothing for guaranteed,’ Porson said darkly.

Slider almost had been, but he let it pass. The old boy was irritable with suffering.

‘Anyway, it’s ours,’ Porson repeated.

‘The SCG doesn’t want it?’ Slider asked.

The SCG was the Serious Crime Group, which had replaced the old Area Major Incident Pool, or AMIP. No doubt the change had brought joy to some desk-bound pillock’s heart, and SCG was one letter shorter than AMIP which must be a great saving on ink; but since the personnel in the one were the exact same as had been in t’other, Slider couldn’t see the point. It was hard for a bloke at the fuzzy end to get excited about a new acronym, especially one that did not trip off the tongue.

‘SCG’s got its plate taken up with the Fulham multiple,’ Porson answered. ‘Plus the Brooke Green terrorist bomb factory – to say nothing of being short-handed, and having four blokes on the sicker.’

Slider met The Syrup’s eyes and refrained from reminding him that they too were short-handed. What with chronic under-recruitment, secondment to the National Crime Squad – not to mention to the SCG itself – plus absence on Roll-out Programmes and the usual attrition of epidemic colds, IBS and back problems – the ongoing response of over-stretched men to a stressful job – there could hardly be a unit of any sort in the Met that was up to strength. But Porson knew all that as well as he did. The SCG were supposed to take the major crimes, which these days generally meant all murders apart from straightforward domestics, but the fact of the matter was that Peter Judson, the head fromage of their own particular SCG, was a cherry-picking bastard who had obviously logged this case as entailing more graft than glory and tossed it back whence it came.

‘After all,’ Porson went on, trying to put a gloss on it, ‘when push comes to shovel, it’s a testament to your firm’s record of success that they want to bung it onto us.’

‘Yes, sir,’ Slider said neutrally.

‘You ought to’ve got a commendation last time, laddie, over that Agnew business. It was pure political bullshine that shot our fox before we could bring it home to roost. So here’s your chance to do yourself a bit of bon. Brace up, knuckle down, and I’ll make sure you get your dues this time, even if I have to stir up puddles till the cows come home.’

The allegories along Porson’s Nile were more than usually deformed this morning, Slider thought, which was generally a sign of emotion or more than usual stress in the old boy. But he knew what he meant. He meant that Slider should put his nose to the wheel and his shoulder to the grindstone, a posture which inevitably left his arse in the right position to be hung out to dry if necessary; and Slider had a feeling, from the preliminary look of the thing, that this one was going to be a long, hard slog.

When he got back to the office, Atherton was there, looking bronzed, fit, rested and generally full of marrowbone jelly. Slider felt a quiet relief at the sight of him. Atherton had been through some tough times recently, including a near nervous breakdown, and there had been moments when Slider had feared to lose him altogether. He’d had other bagmen in a long career, but none that he would have also called his friend.

Atherton did not immediately look up, being engaged with the Guardian crossword. DC McLaren was hanging over his shoulder, a drippy bacon sandwich suspended perilously on the way to his mouth.

‘I can’t read your writing,’ McLaren complained. ‘What’s that?’

‘Aardvark.’

‘With two a’s?’ McLaren objected.

‘It’s a name it made up for itself when it heard Noah was boarding the ark in alphabetical order,’ Atherton explained kindly. ‘The zebras were exceptionally pissed off, I can tell you. That’s why they turned up in their pyjamas – as a kind of protest.’

‘Now I know you’re back,’ Slider said. Atherton looked up, and McLaren straightened just in time for the melted butter to drip onto his front – which was used to it – instead of Atherton’s back. Atherton was a classy dresser, and it would have been an act of vandalism akin to gobbing on the Mona Lisa.

‘No need to ask if you had a good time,’ Slider said. ‘You’re looking disgustingly pleased with yourself.’

‘Why not?’ Atherton agreed. ‘A fortnight of sunshine and unfeasibly energetic sexual activity. And now a nice meaty corpse to get our teeth into.’

‘Some people have strange tastes. How did you know, anyway?’

‘Bad news has wings. Maurice was talking to Paul Beynon from the SCG while you were upstairs.’

‘I knew him at Kensington,’ McLaren said. ‘He rung to give me the gen.’ His time at Kensington was his Golden Age, source of all legend. Amazingly, it seemed he had been popular there. At all events, they were always ringing him up for a bunny, and vice versa.

‘So it seems I just got back in time,’ Atherton said.

‘Yeah, from what you said, another day’d’ve killed you,’ McLaren said lubriciously.

‘How’s Sue?’ Slider asked.

Atherton smiled. ‘You’ll never know.’

McLaren pricked up his ears. ‘Oh, is that who you were with? That short bird I saw you with that time? Blimey, you still going with her?’

His surprise was understandable, if tactless, for Atherton had always demanded supermodel looks as basic minimum, and Sue – a colleague of Joanna’s – was neither willowy nor drop-dead gorgeous. She had something, however, that melted Atherton’s collar studs. But he didn’t rise to McLaren. He merely looked sidelong and said, ‘You know the old saying, Maurice: better to have loved a short girl than never to have loved a tall.’

‘Right, shall we get on with it?’ Slider interposed. The rest of his team, bar Hollis and Mackay who were still at the scene, had come in behind him. ‘With no identification on the corpse, we’ve got more work even than usual ahead of us. In fact, I expected to find you all hard at it already,’ he complained.

‘We have been. Hive of activity, guv,’ McLaren said smartly. ‘Just waiting for you to get back to see how you wanted it set up.’

‘Never mind that Tottenham. When did I ever want it set up any differently? Here’s the Polaroids from the scene. And I shall want a sketch map of the immediate area up on the wall. Get on with it, Leonardo.’

McLaren stuffed the last of the sandwich in his mouth. ‘Right, guv,’ he said indistinctly. ‘Get you a cuppa first?’

‘From the canteen? Yes, all right, might as well. It’ll be a long day.’

‘Get me one too, Maurice,’ Anderson said.

‘Slice cake with it?’

Anderson boggled. ‘You what? Turn you stone blind.’

McLaren shrugged and hurried off.

Atherton shoved the newspaper into his drawer and unfurled his elegant height to the vertical. ‘He probably thought you meant DiCaprio,’ he observed to Slider.

The park keeper, Ken Whalley, was in the interview room, his hands wrapped round a mug of tea as if warming them on a cold winter’s day. He had a surprisingly pale face for an outdoor worker, pudgy and nondescript, with strangely formless features, as if he had been fashioned by an eager child out of pastry but not yet cooked. Two minutes after turning your back on him it would be impossible to remember what he looked like. Perhaps to give himself some distinction he had grown his fuzzy brown hair down to his collar where it nestled weakly, having let go the top of his head as an unequal struggle.

He looked desperately upset, which perhaps was not surprising. However un-mangled this particular corpse was, it was one more than most people ever saw in a lifetime, and finding it must have been unsettling.

Slider, sitting opposite, made himself as unthreatening as possible. ‘So, tell me about this morning. What time did you arrive at the park?’

Whalley looked up over the rim of the mug like a victim. He had those drooping lower lids, like a bloodhound, that showed the red, which made him look more than ever pathetic. ‘I’ve already told the other bloke all about it,’ he complained. ‘Back at the park. I told the copper first, and then I had to tell that plain-clothes bloke an’ all.’

‘I know, it’s a pain the way you’ll have to keep repeating the story,’ Slider sympathised, ‘but I’m afraid that’s the way it goes. This is a murder investigation, you know.’ Whalley flinched at the ‘M’ word and offered no more protest. ‘What time did you arrive?’

Whalley sighed and yielded. ‘Just before a’pass seven. I’m supposed to open up at a’pass.’

‘At the South Africa Road end?’ A nod. ‘And what time did you leave home?’

He seemed to find this question surprising. At last he said, as if Slider ought to have known, ‘But I only live across the road. I got a flat in Davis House. Goes with the job.’

‘I see. All right, when you got there, were the gates open or shut?’

‘Shut. They was shut,’ he said quickly.

‘And locked? How do you lock them?’

‘With a chain and padlock.’

‘And were the chain and padlock still in place, and locked?’

‘Yeah, course they were,’ Whalley said defensively.

‘And what about the Frithville Gardens end?’

‘I never went down there. Once I saw that bloke in the playground I just rang you lot, and then I never went nowhere else.’ He looked nervously from Slider to Atherton and back. ‘Look, I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking I never locked up properly last night.’

‘I didn’t say that.’

‘Well I did. I done everything right, same as always. It’s not my bleedin’ fault ’e got done!’

‘All right, calm down. Nobody’s accusing you of anything,’ Atherton said. ‘We just need to get it all straight, that’s all. Once we’ve got your statement written down we probably won’t need to bother you again.’

Whalley seemed reassured by this. ‘All right,’ he said at last, putting the mug down and wiping his lips on the back of his sleeve. ‘What j’wanna know?’

‘Tell me about locking up last night,’ Slider said. ‘What time it was, and exactly what you did.’

‘Well, it was about a’pass nine. I’m s’pose to lock up at dusk, which is generally about arf hour after sunset, but it’s up to me. I generally lock up earlier in winter, ’cause there’s not so many people about. It’s a cut-through, but there’s no lights in the park, so we can’t leave it open after dark. Course, people still want to take the short cut, and they used to bunk over the gate, so we had them new gates put on down the Frithville end, with all the pointy stuff on top.’

Slider had seen them: irregular metal extrusions, vaguely flame-shaped, topped the high gates, looking as if they were meant for decoration but in fact a fairly good deterrent. Of course, a really determined person could climb over anything, but the flames prevented ‘bunking’ – hitching oneself up onto one’s stomach and then swinging the legs over – which would deter the casual cutter-through.

Whalley went on, ‘But in summer it stays light longer and it depends what I’m doing what time I shut up. But anyway, I went over a’pass nine with the chains and padlocks. What I do, I shut the South Africa gate but I don’t lock it, then I walk through telling everyone it’s closing. Then I lock the Frithville gate, and walk back, make sure everyone’s out, then lock the South Africa gates.’

‘And that’s what you did last night?’

There were beads of sweat on Whalley’s upper lip. ‘That’s what I’m telling you, inni? I did everything just like normal and then I went home.’

‘Have you ever seen deceased before?’

‘No, I never seen him before in me life,’ Whalley said emphatically. ‘I don’t know who he is, and that’s the truth.’ He wiped his lips again.

‘Did you see him in the park anywhere before you locked up?’

‘What, j’fink I wouldn’t a noticed a bleedin’ dead body?’ Whalley said indignantly.

‘No, I meant did you see him alive? Was he hanging around, perhaps?’

‘I dunno. No, I never.’

‘Was there anyone in the park who took your notice? Anyone unusual or suspicious-looking?’

Whalley drew up his shoulders and spread his hands defensively. ‘Look, I don’t go checking up on people,’ he whined. ‘It’s not my job. I just go through telling ’em it’s closing. Everyone was out before I locked up, that’s all I know. You can’t put it on me. F’ cryin’ out loud!’

‘It’s just,’ Slider said gently, ‘that you said you didn’t go down to the Frithville gate this morning, but when one of our constables went down there, there was no padlock and chain. The gates were shut, but they weren’t locked.’

Whalley stared a long time, his lips moving as if rehearsing his answer. Then at last he licked them and said, ‘Someone must’ve took ’em.’ Slider waited in silence. Whalley looked suddenly relieved. ‘Yeah, someone must’ve cut through ’em. You could cut that chain all right with heavy bolt-cutters.’

Walking away from the interview room, Atherton eyed his boss’s thoughtful frown and said, ‘Well?’

‘Well?’ Slider countered. ‘How did you like Mr Whalley?’

‘Thick as a whale sandwich, and more chicken than the Colonel. What did you think of him?’

‘I don’t like it when they start supplying answers to questions they’ve no business answering,’ Slider said.

‘That stuff about bolt-cutters?’

‘If you were breaking into the park for nefarious purposes, would you bother to take the padlock and chain away with you? Or having cut through them, would you just leave them lying where they fell?’

‘I see what you mean. So you think Whalley’s lying? He’s nervous enough.’

‘In his position I’d be nervous, whether I was lying or not. When a corpse is found on your watch it doesn’t bode well even if you’re innocent. It’s possible he merely forgot to lock the gates, and doesn’t want to admit it in view of the consequences.’

‘Point.’

‘The other possibility is that he’s in on it in some way. But what “it” is, we can’t know until we can find out who deceased is.’

‘Well, I can’t see Whalley as a criminal conspirator,’ Atherton said. ‘He’s a pathetic little runt.’

‘I expect you’re right. It’s just the padlock and chain not being there that bothers me. Our corpse was too nattily dressed for climbing over gates. Especially gates with pointy bits on the top.’

‘You think he had an appointment in the park?’

Slider shrugged. ‘Whatever he went there for, he went there. Alive or dead, he went through one of the gates or over it, and I can’t make myself believe in over.’

In the post-mortem room of the hospital’s pathology department, Freddie Cameron, the forensic pathologist, presented to the world an appearance as smooth as a racehorse’s ear. It was his response to the unpleasantness of much of his work to cultivate an outward perfection. His suiting was point-device, his linen immaculate; his waistcoat was a poem of nicely calculated audacity and his bowtie du jour was crimson with an old gold spot.

All this loveliness, of course, was concealed as soon as he put on the protective clothing, but still he was positively jaunty as he shaped up to the corpse.

‘Anything’s better than facing another pair of congested lungs, old bean,’ he said when Slider queried his pleasure. ‘I’m even beginning to eye my bath sponge askance. This flu epidemic seems to have gone on for ever. Good to see you back,’ he added to Atherton. ‘Good holiday? You’re looking very juvenile and jolly.’

‘Fully functioning on all circuits,’ Atherton admitted.

‘So, you’ve no ID on our friend here?’ Cameron asked.

‘Not so far,’ Slider said.

‘Well, I’ll take the fingerprints for you, and a blood sample. Chap looks a bit tasty, to my view.’

‘I agree. Everything about him suggests there’s a good chance he’ll feature somewhere in our hall of fame.’

‘Right. Well, as soon as my assistant arrives, we’ll begin. Ah, here she is. Sandra, this is my old friend Bill Slider. Sandra Whitty.’

Slider shook hands. She was an attractive young woman, sensationally busted under her lab coat. Her lovely profile preceded her into a little pool of held breath which had gathered round the table; broken a moment later as McLaren muttered fervently, ‘Blimey, she takes up a lot of room!’

Why is it we’re all so childish about bosoms, Slider wondered. He wasn’t immune himself. Charlie Dimmock had a lot to answer for. He met Miss Whitty’s eye apologetically. ‘Excuse the reptile.’

Fortunately, she only looked amused. ‘That’s all right, I keep pets myself.’

She obviously knew what she was doing, and handled the body with an easy strength as she and Freddie removed the clothing and put it into the bags McLaren held out. There was nothing in any of the pockets to identify the deceased. One jacket pocket yielded cigarettes – Gitanes, a rather surprising choice – and a throwaway lighter. The other contained a quantity of change and a crumpled but clean handkerchief. The inside jacket pocket contained a fold of notes held with a elastic band. When McLaren unfolded and counted them, it came to over a thousand pounds, in fifties, twenties and tens.

‘Now there’s a thing you don’t see every day,’ Freddie said. He breathed in deeply. ‘Ah, money! I can almost smell the mint.’

‘Evidently robbery from the person was not a factor,’ Atherton said.

‘But there’s no wallet, driving licence, credit card, or any of the gubbins a man carries about,’ Slider said. ‘Was he unusually self-effacing, or did the murderer cop the lot?’

‘If he did, why wouldn’t he take the money?’ Freddie added. ‘Only fair, after taking the trouble to kill the chappie.’

‘I’d have taken the jacket,’ Atherton said. ‘It’s a lovely piece of leather. I wonder where he got it?’ He looked at the label sewn inside just under the collar. ‘“Emporio Firenze”,’ he read. ‘Never heard of them. Still, it’s very nice.’

‘Nice watch, too,’ Sandra said.

‘Is that a Rolex?’ Atherton asked, leaning forward.

‘It only thinks it is,’ she said succinctly. ‘Good fake, though. Date, phases of the moon, two different time zones, alarm, stopwatch function and integral microwave oven and waffle maker. Not cheap.’

‘How do you know so much about men’s watches?’

‘I’ve handled a few,’ she said. Slider could see Atherton working it out and felt a mild urge to kick him. When it came to women he had all the self-restraint of an Alsatian puppy on a bowling green.

‘Look here, Bill,’ Freddie said a moment later. ‘Someone has been into the pockets. You see here, the left inside pocket is stained with blood where it rested against the wound. Now, over here, a tiny smear of blood on the right inside pocket. Someone’s checked the contents of the left pocket and then transferred the blood on hi. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...