- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

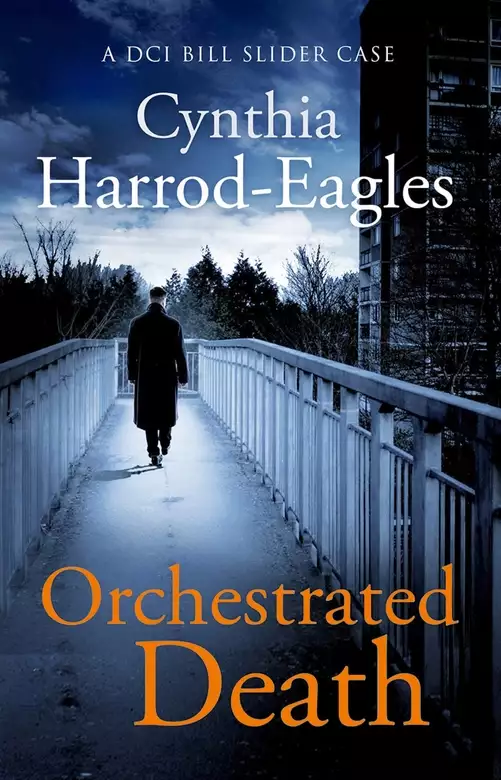

Synopsis

'An outstanding series' NEW YORK TIMES

A Bill Slider Mystery

Detective Inspector Bill Slider - middle-class, middle-aged, and middle-of-the-road - is never going to make it to Scotland Yard. He's spent most of his working life at Shepherd's Bush nick, and stopped minding long ago about being passed over for promotion.

But then the unidentifiable body of a woman turns up on his patch, and suddenly Slider and his partner Atherton have a chance to prove themselves.

As they wrestle with an investigation, in which the only clues are a priceless Stradivarius and a giant tin of olive oil, everyone - most of all Slider himself - is wondering whether this latest crisis will make or break the steely-eyed detective.

Praise for the Bill Slider series:

'Slider and his creator are real discoveries'

Daily Mail

'Sharp, witty and well-plotted'

Times

'Harrod-Eagles and her detective hero form a class act. The style is fast, funny and furious - the plotting crisply devious'

Irish Times

Release date: September 1, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 224

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Orchestrated Death

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

He and Atherton, his sergeant, had been working late. They had been out on loan to the Notting Hill Drug Squad to help stake out a house where some kind of major deal was supposed to be going down. He had called Irene to say that he wouldn’t be back in time to take her to the dinner party she had been looking forward to, and then spent the evening sitting in Atherton’s powder-blue Sierra in Pembridge Road, watching a dark and silent house. Nothing happened, and when the Notting Hill CID man eventually strolled over to put his head through their window and tell them they might as well push off, they were both starving.

Atherton was a tall, bony, fair-skinned, high-shouldered young man, who wore his toffee-coloured hair in the style made famous by David McCallum in The Man From UNCLE in the days when Atherton was still too young to stay up and watch it. He looked at his watch cheerfully and said there was just time for a pint at The Dog and Scrotum before Hilda put the towels up.

It wasn’t really called The Dog and Scrotum, of course. It was The Dog and Sportsman in Wood Lane, one of those gigantic arterial road pubs built in the fifties, all dingy tiled corridors and ginger-varnished doors, short on comfort, echoing like a swimming pool, smelling of Jeyes and old smoke and piss and sour beer. The inn sign showed a man in tweeds and a trilby cradling a gun in his arm, while a black labrador jumped up at him – presumably in an excess of high spirits, but Atherton insisted it was depicted in the act of sinking its teeth into its master’s hairy Harris crutch.

It was a sodawful pub really, Slider reflected, as he did every time they went there. He didn’t like drinking on his patch, but since he lived in Ruislip and Atherton lived in the Hampstead-overspill bit of Kilburn, it was the only pub reasonably on both their ways. Atherton, whom nothing ever depressed, said that Hilda, the ancient barmaid, had hidden depths, and the beer was all right. There was at least a kind of reassuring anonymity about it. Anyone willing to be a regular of such a dismal place must be introspective to the point of coma.

So they had two pints while Atherton chatted up Hilda. Ever since he had bought the Sierra, Atherton had been weaving a fiction that he was a software rep, but Slider was sure that Hilda, who looked as though the inside of a magistrates’ court would hold no surprises for her, knew perfectly well that they were coppers. Rozzers, she might even call them; or Busies? No, that was a bit too Dickensian: Hilda couldn’t be more than about sixty-eight or seventy. She had the black, empty eyes of an old snake, and her hands trembled all the time except, miraculously, when she pulled a pint. It was hard to tell whether she knew everything that went on, or nothing. Certainly she looked as though she had never believed in Father Christmas or George Dixon.

After the beer, they decided to go for a curry; or rather, since the only place still open at that time of night would be an Indian restaurant, they decided which curry-house to patronise – the horrendously named Anglabangla, or The New Delhi, which smelled relentlessly of damp basements. And then home, to the row with Irene, and indigestion. Both were so much a part of any evening that began with working late, that nowadays when he ate in an Indian restaurant it was with an anticipatory sense of unease.

After a bit of preliminary squaring up. Irene pitched into the usual tirade, all too familiar to Slider for him to need to listen or reply. When she got to the bit about What Did He Think It Was Like To Sit By The Phone Hour After Hour Wondering Whether He Was Alive Or Dead? Slider unwisely muttered that he had often wondered the same thing himself, which didn’t help at all. Irene had in any case little sense of humour, and none at all where the sorrows of being a policeman’s wife were concerned.

Slider had ceased to argue, even to himself, that she had known what she was letting herself in for when she married him. People, he had discovered, married each other for reasons which ranged from the insufficient to the ludicrous, and no one ever paid any attention to warnings of that sort. He himself had married Irene knowing what she was like, and despite a very serious warning from his friend-and-mentor O’Flaherty, the desk sergeant at Shepherd’s Bush.

‘For God’s sake, Billy darlin’,’ the outsize son of Erin had said anxiously, thrusting forward his veined face to emphasise the point, ‘you can’t marry a woman with no sense-a-humour.’

But he had gone and done it all the same, though in retrospect he could see that even then there had been things about her that irritated him. Now he lay in bed beside her and listened to her breathing, and when he turned his head carefully to look at her, he felt the rise inside him of the vast pity which had replaced love and desire. Tout comprendre c’est tout embêter, Atherton said once, and translated it roughly as ‘Once you know everything it’s boring’. Slider pitied Irene because he understood her, and it was that fatal ability of his to see both sides of every question which most irritated her, and made even their quarrels inconclusive.

He could sense the puzzlement under her anger, because she wanted to be a good wife and love him, but how could she respect anyone so ineffectual? Other people’s husbands Got On, got promoted and earned more money. Slider believed his work was important and that he did it well, but Irene could not value an achievement so static, and sometimes he had to struggle not to absorb her values. If once he began to judge himself by her criteria, it would be All Up With Slider.

His intestines seethed and groaned like an old steam clamp as the curry and beer resolved themselves into acid and wind. He longed to ease his position, but knew that any shift of weight on his part would disturb Irene. The Slumber-well Dreamland Deluxe was sprung like a young trampoline, and overreaction was as much in its nature as in a Cadillac’s suspension.

He thought of the evening he had spent, apparently resultless as was so much of his police work. Then he thought of the one he might have spent, of disguised food and tinkly talk at the Harpers’, who always had matching candles and napkins on their dinner-table, but served Le Piat d’Or with everything.

The Harpers had good taste, according to Irene. You could tell they had good taste, because everything in their house resembled the advertising pages of the Sundry Trends Colour Supplement. Well, it was comforting to know you were right, he supposed; to be sure of your friends’ approval of your stripped pine, your Sanderson soft furnishings, your oatmeal Berber, your Pampas bathroom suite, your numbered limited-edition prints of bare trees on a skyline in Norfolk, the varnished cork tiles on your kitchen floor, and the excitingly chunky stonewear from Peter Jones. And when you lived on an estate in Ruislip where they still thought plastic onions hanging in the kitchen were a pretty cute idea, it must all seem a world of sophistication apart.

Slider had a sudden, familiar spasm of hating it all; and especially this horrible Ranch-style Executive Home, with its picture windows and no chimneys, its open-plan front garden in which all the dogs of the neighbourhood could crap at will, with its carefully designed rocky outcrop containing two poncey little dwarf conifers and three clumps of heather; this utterly undesirable residence on a new and sought-after estate, at the still centre of the fat and neutered universe of the lower middle classes. Here struggle and passion had been ousted by Terence Conran, and the old, dark and insanitary religions had been replaced by the single lustral rite of washing the car. A Homage to Catatonia. This was it, mate, authentic, guaranteed, nice-work-if-you-can-get-it style. This was Eden.

The spasm passed. It was silly really, because he was one of the self-appointed guardians of Catatonia; and because, in the end, he had to prefer vacuity to vice. He had seen enough of the other side, of the appalling waste and sheer stupidity of crime, to know that the most thoughtless and smug of his neighbours was still marginally better worth protecting than the greedy and self-pitying thugs who preyed on him. You’re a bastion, bhoy, he told himself in O’Flaherty’s voice. A right little bastion.

The phone rang.

Slider plunged and caught it before its second shriek, and Irene moaned and stirred but didn’t wake. She had been hankering after a Trimphone, using as an excuse the theory that it would disturb her less when it rang at unseasonable hours. There were so many Trimphones down their street now that the starlings had started imitating them, and Slider had made one of his rare firm stands. He didn’t mind being woken up in the middle of the night, but he was damned if he’d be warbled at in his own home.

‘Hullo, Bill. Sorry to wake you up, mate.’ It was Nicholls, the sergeant on night duty.

‘You didn’t actually. I was already awake. What’s up?’

‘I’ve got a corpus for you.’ Nicholls’ residual Scottish accent made his consonants so deliberate it always sounded like corpus. ‘It’s at Barry House, New Zealand Road, on the White City Estate.’

Slider glanced across at the clock. It was a quarter past five. ‘Just been found?’

‘It came in on a 999 call – anonymous tip-off, but it took a while to get on to it, because it was a kid who phoned, and naturally they thought it was a hoax. But Uniform’s there now, and Atherton’s on his way. Nice start to your day.’

‘Could be worse,’ Slider said automatically, and then seeing Irene beginning to wake, realised that if he didn’t get on his way quickly before she woke properly, it most certainly would be.

The White City Estate was built on the site of the Commonwealth Exhibition, for whose sake not only a gigantic athletics stadium, but a whole new underground station had been built. The vast area of low-rise flats was bordered on one side by the Western Avenue, the embryo motorway of the A40. On another side lay the stadium itself, and the BBC’s Television Centre, which kept its back firmly turned on the flats and faced Wood Lane instead. On the other two sides were the teeming back streets of Shepherd’s Bush and Acton. In the thirties, the estate had been a showpiece, but it had become rather dirty and depressing. Now they were even pulling down the stadium, where dogs had been racing every Thursday and Saturday night since Time began.

Slider had had business on the estate on many an occasion, usually just the daily grind of car theft and housebreaking; though sometimes an escaped inmate of the nearby Wormwood Scrubs prison would brighten up everyone’s day by going to earth in the rabbit warren of flats. It was a good place to hide: Slider always got lost. The local council had once put up boards displaying maps with an alphabetical index of the blocks, but they had been eagerly defaced by the waiting local kids as soon as they were erected. Slider was of the opinion that either you were born there, or you never learnt your way about.

In memory of the original exhibition, the roads were named after outposts of the Empire – Australia Road, India Way and so on – and the blocks of flats after its heroes – Lawrence, Rhodes, Nightingale. They all looked the same to Slider, as he drove in a dazed way about the identical streets. Barry House, New Zealand Road. Who the hell was Barry anyway?

At last he caught sight of the familiar shapes of panda and jam sandwich, parked in a yard framed by two small blocks, five storeys high, three flats to a floor, each a mirror image of the other. Many of the flats were boarded up, and the yard was half blocked by building equipment, but the balconies were lined with leaning, chattering, thrilled onlookers, and despite the early hour the yard was thronged with small black children.

A tall, heavy, bearded constable was holding the bottom of the stairway, chatting genially with the front members of the crowd as he kept them effortlessly at bay. It was Andy Cosgrove who, under the new regime of community policing, had this labyrinth as his beat, and apparently not only knew but also liked it.

‘It’s on the top floor I’m afraid, sir,’ he told Slider as he parted the bodies for him, ‘and no lift. This is one of the older blocks. As you can see, they’re just starting to modernise it.’

Slider cocked an eye upwards. ‘Know who it is?’

‘No, sir. I don’t think it’s a local, though. Sergeant Atherton’s up there already, and the surgeon’s just arrived.’

Slider grimaced. ‘I’m always last at the party.’

‘Penalties of living in the country, sir,’ Cosgrove said, and Slider couldn’t tell if he were joking or not.

He started up the stairs. They were built to last, of solid granite, with cast-iron banisters and glazed tiles on the walls, all calculated to reject any trace of those passing up them. Ah, they don’t make ’em like that any more. On the top-floor landing, almost breathless, he found Atherton, obscenely cheerful.

‘One more flight,’ he said encouragingly. Slider glared at him and tramped, grey building rubble gritting under his soles. The stairs divided the flats two to one side and one to the other. ‘It’s the middle flat. They’re all empty on this floor.’ A uniformed constable, Willans, stood guard at the door. ‘It’s been empty about six weeks, apparently. Cosgrove says there’s been some trouble with tramps sleeping in there, and kids breaking in for a smoke, the usual things. Here’s how they got in.’

The glass panel of the front door had been boarded over. Atherton demonstrated the loosened nails in one corner, wiggled his fingers under to show how the knob of the Yale lock could be reached.

‘No broken glass?’ Slider frowned.

‘Someone’s cleaned up the whole place,’ Atherton admitted sadly. ‘Swept it clean as a whistle.’

‘Who found the body?’

‘Some kid phoned emergency around three this morning. Nicholls thought it was a hoax – the kid was very young, and wouldn’t give his name – but he passed it on to the night patrol anyway, only the panda took its time getting here. She was found about a quarter to five.’

‘She?’ Funny how you always expect it to be male.

‘Female, middle-twenties. Naked,’ Atherton said economically.

Slider felt a familiar sinking of heart. ‘Oh no.’

‘I don’t think so,’ Atherton said quickly, answering the thought behind the words. ‘She doesn’t seem to have been touched at all. But the doc’s in there now.’

‘Oh well, let’s have a look,’ Slider said wearily.

Apart from the foul taste in his mouth and the ferment in his bowels, he had a small but gripping pain in the socket behind his right eye, and he longed inexpressibly for untroubled sleep. Atherton on the other hand, who had shared his debauch and presumably been up before him, looked not only fresh and healthy, but happy, with the intent and eager expression of a sheepdog on its way up into the hills. Slider could only trust that age and marriage would catch up with him, too, one day.

He found the flat gloomy and depressing in the unnatural glare from the spotlight on the roof opposite – installed to deter vandals, he supposed. ‘The electricity’s off, of course,’ Atherton said, producing his torch. Boy scout, thought Slider savagely. In the room itself DC Hunt was holding another torch, illuminating the scene for the police surgeon, Freddie Cameron, who nodded a greeting and silently gave Slider place beside the victim.

She was lying on her left side with her back to the wall, her legs drawn up, her left arm folded with its hand under her head. Her dark hair, cut in a long pageboy bob, fell over her face and neck. Slider could see why Cosgrove thought she wasn’t a resident. She was what pathologists describe as ‘well-nourished’: her flesh was sleek and unblemished, her hair and skin had the indefinable sheen of affluence that comes from a well-balanced protein-based diet. She also had an expensive tan, which left a white bikini-mark over her hips.

Slider picked up her right hand. It was icy cold, but still flexible: a strong, long-fingered, but curiously ugly hand, the fingernails cut so short that the flesh of the fingertips bulged a little round them. The cuticles were well-kept and there were no marks or scratches. He put the hand down and drew the hair back from the face. She looked about twenty-five – perhaps younger, for her cheek still had the full and blooming curve of extreme youth. Small straight nose, full mouth, with a short upper lip which showed the white edge of her teeth. Strongly marked dark brows, and below them a semicircle of black eyelashes brushing the curve of her cheekbone. Her eyes were closed reposefully. Death, though untimely, had come to her quietly, like sleep.

He lifted her shoulder carefully to raise her a little against the hideously papered wall. Her small, unripe breasts were no paler than her shoulders – wherever she had sunbathed last year, it had been topless. Her body had the slender tautness of unuse; below her flat golden belly, the stripe of white flesh looked like velvet. He had a sudden vision of her, strutting along a foreign beach under an expensive sun, carelessly self-conscious as a young foal, all her life before her, and pleasure still something that did not surprise her. An enormous, unwanted pity shook him; the dark raspberry nipples seemed to reproach him like eyes, and he let her subside into her former position, and abruptly walked away to let Cameron take his place.

He walked around the rest of the flat. There were three bedrooms, living-room, kitchen, bathroom and WC. The whole place was stripped bare, and had been swept clean. No litter of tramps and children, hardly even any dust. He remembered the grittiness of the stairs outside and sighed. There would be nothing here for them, no footprints, no fingerprints, no material evidence. What had become of her clothes and handbag? He felt already a sense of unpleasant anxiety about this business. It was too well organised, too professional. And the wallpaper in each room was more depressing than the last.

Atherton appeared at the door, startling him. ‘Dr Cameron wants you, guv.’

Freddie Cameron looked up as Slider came in. ‘No sign of a struggle. No visible wounds. No apparent marks or bruises.’

‘A fine upstanding body of negatives,’ Slider said. ‘What does that leave? Heart? Drugs?’

‘Give me a chance,’ Cameron grumbled. ‘I can’t see anything in this bloody awful light. I can’t find a puncture, but it’s probably narcotics – look at the pupils.’ He let the eyelids roll back, and picked up the arms one by one, peering at the soft crook of the elbow. ‘No sign of usage or abusage. Of course you can see from the general condition that she wasn’t an addict. Could have taken something by mouth, I suppose, but where’s the container?’

‘Where are her clothes, for the matter of that,’ said Slider. ‘Unless she walked up here in the nude, I think we can rule out suicide. Someone was obviously here.’

‘Obviously,’ Cameron said drily. ‘I can’t help you much, Bill, until I can examine her by a good light. My guess is an overdose, probably by mouth, though I may find a puncture wound. No marks on her anywhere at all, except for the cuts, and they were inflicted post mortem.’

‘Cuts?’

‘On the foot.’ Cameron gestured. Slider hunkered down and stared. He had not noticed before, but the softly curled palm of her foot had been marked with two deep cuts, roughly in the shape of a T. They had not bled, only oozed a little, and the blood had set darkly. Left foot only – the right was unmarked. The pads of the small toes rimmed the foot like fat pink pearls. Slider began to feel very bad indeed.

‘Time of death?’ he managed to say.

‘Eight hours, very roughly. Rigor’s just starting. I’ll have a better idea when it starts to pass off.’

‘About ten last night, then?’ Slider stared at the body with deep perplexity. Her glossy skin was so out of place against the background of that disgusting wallpaper. ‘I don’t like it,’ he said aloud.

Cameron put his hand on Slider’s shoulder comfortingly. ‘There is no sign of forcible sexual penetration,’ he said.

Slider managed to smile. ‘Anyone else would simply have said rape.’

‘Language, my dear Bill, is a tool – not a blunt instrument. Anyway, I’ll be able to confirm it after the post. She’ll be as stiff as a board by this afternoon. Let me see – I can do it Friday afternoon, about four-ish, if it’s passed off by then. I’ll let you know, in case you want to come. Nice-looking kid. I wonder who she is? Someone must be missing her. Ah, here’s the photographer. Oh, it’s you, Sid. No lights. I hope you’ve got yours with you, dear boy, because it’s as dark as a mole’s entry in here.’

Sid got to work, complaining uniformly about the conditions as a bee buzzes about its work. Cameron turned the body over so that he could get some mugshots, and as the brown hair slid away from the face, Slider leaned forward with sudden interest.

‘Hullo, what’s that mark on her neck?’

It was large and roughly round, about the size of a half-crown, an area of darkened and roughened skin about halfway down the left side of the neck; ugly against the otherwise flawless whiteness.

‘It looks like a bloody great lovebite,’ Sid said boisterously. ‘I wouldn’t mind giving her one meself.’ He had captured for police posterity some gruesome objects in his time, including a suicide-by-hanging so long undiscovered that only its clothes were holding it together. Decomposing corpses held no horrors for him, but Slider was interested to note that something about this one’s nude composure had unnerved the photographer too, making him overcompensate.

‘Is it a bruise? Or a burn – a chloroform burn or something like that?’

‘Oh no, it isn’t a new mark,’ Cameron said. ‘It’s more like a callus – see the pigmentation, where something’s rubbed there – and some abnormal hair growth, too, look, here. Whatever it is, it’s chronic’

‘Chronic? I’d call it bloody ugly,’ Sid said.

‘I mean it’s been there a long time,’ Cameron explained kindly. ‘Can you get a good shot of it? Good. All right, then, Bill – seen all you want? Let’s get her out of here, then. I’m bloody cold.’

A short while later, having seen the body lifted onto a stretcher, covered and removed, Cameron paused on his way out to say to Slider, ‘I suppose you’ll want to have the prints and dental records toot sweet! Not that her teeth’ll tell you much – a near perfect set. Fluoride has a lot to answer for.’

‘Thanks Freddie,’ Slider said absently. Someone must be missing her. Parents, flatmates, boyfriend – certainly, surely, a boyfriend? He stared at the bare and dirty room: Why here, for heaven’s sake?

‘The fingerprint boys are here, guv,’ Atherton said in his ear, jerking him back from the darkness.

‘Right. Start Hunt and Hope on taking statements,’ Slider said. ‘Not that anyone will have seen anything, of course – not here.’

The long grind begins, he thought. Questions and statements, hundreds of statements, and nearly all of them would boil down to the Three Wise Monkeys, or another fine regiment of negatives.

In detective novels, he thought sadly, there was always someone who, having just checked his watch against the Greenwich Time Signal, glanced out of the window and saw the car with the memorable numberplate being driven off by a tall one-legged red-headed man with a black eyepatch and a zigzag scar down the left cheek. I could tell ’e wasn’t a gentleman, Hinspector, ’cause ’e was wearing brown boots.

‘Might be a good idea to get Cosgrove onto taking statements,’ Atherton was saying. ‘At least he speaks the lingo.’

A grey sky, which Slider had thought was simply pre-dawn greyness, settled in for the day, and resolved itself into a steady, cold and sordid rain.

‘All life is at its lowest ebb in January,’ Atherton said. ‘Except, of course, in Tierra del Fuego, where they’re miserable all year round. Cheese salad or ham salad?’ He held up a roll in each hand and wiggled them a little, like a conjurer demonstrating his bona fides.

Slider looked at them doubtfully. ‘Is that the ham I can see hanging out of the side?’

Atherton tilted the roll to inspect it, and the pink extrusion flapped dismally, like a ragged white vest which had accidentally been washed in company with a red T-shirt. ‘Well, yes,’ he admitted. ‘All right, then,’ he conceded, ‘cheese salad or rubber salad?’

‘Cheese salad.’

‘I was afraid you’d say that. I never thought you were the sort to pull rank, guv,’ Atherton grumbled, passing it across. ‘Funny how the act of making sandwiches brings out the Calvinist in us. If you enjoy it, it must be sinful.’ He looked for a moment at the bent head and sad face of his superior. ‘I could make you feel good about the rolls,’ he offered gently. ‘I could tell you about the pork pies.’

The corner of Slider’s mouth twitched in response, but only briefly. Atherton let him be, and went on with his lunch and his newspaper. They had made a para in the lunchtime Standard:

The body of a naked woman has been discovered in an empty flat on the White City Estate in West London. The police are investigating.

Short and nutty, he thought. He was going to pass it over to Slider, and then decided against disturbing his brown study. He knew Slider well, and knew Irene as well as he imagined anyone would ever want to, and guessed that she had. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...