- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

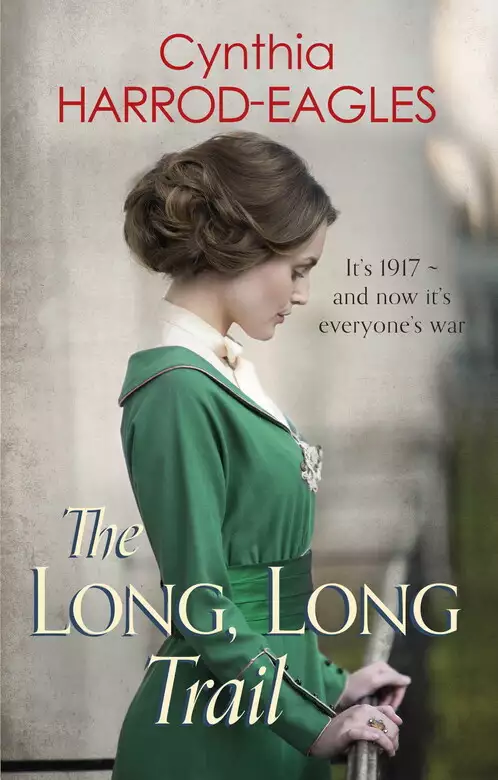

The fourth book in the War at Home series by the author of The Morland Dynasty novels. Set against the evocative backdrop of World War I, this is an epic family drama featuring the Hunters and their servants.

Release date: June 15, 2017

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

The Long, Long Trail

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

Sadie jerked awake from a deep sleep with the realisation that there was someone in the room. She sat up, heart thumping, and realised it was only Peter, standing in the doorway, the light from his ‘air-raid’ torch partly obscured by his fingers.

‘What is it?’ she asked.

‘It’s Christmas,’ he said.

Beyond Peter’s back, the house was in darkness. If the servants had been up there would have been light from the hall below.

‘It’s too early,’ she groaned. ‘Go back to bed.’ It was bitterly cold, too. Peter, in his pyjamas, was shivering, shifting from foot to foot. ‘Hasn’t Father Christmas been?’ she asked.

‘I know it isn’t Father Christmas,’ he said. ‘I know it’s Mum and Dad.’ He was ten years old, and the war had been going on for more than two of those. Childhood was different, these days. Illusions were harder to hold on to.

‘What’s the matter, then?’ she asked.

He was silent a moment, then said mournfully, ‘It doesn’t seem a bit like Christmas.’

She softened. ‘Do you want to bring your stocking in here? Don’t make a noise, though.’

He scampered away. She put on her bedside lamp, and reached for her dressing-gown, which she had spread across the bed for extra warmth, to put it on. Nailer had been curled under it, across the foot of the bed. He lifted an enquiring head, then lowered it again, sticking his nose back under his belly like a cat. Down in the hall, the Vienna clock struck a slow, thoughtful five. Her own stocking was hanging on one of the bed-knobs, but she could happily have waited until morning for it. She was too old for a stocking, really – she would be nineteen in a few weeks’ time – but she knew her parents were making an effort to keep Christmas as much like itself as possible, for all their sakes.

But Bobby was dead – the realisation hit her all over again, with astonishment and pain, as it did almost every day on waking. And David had been wounded, invalided out of the army, and who knew if he would ever walk properly again? Peter was right: it didn’t seem a bit like Christmas.

He came back with his stocking and jumped into bed with her, his icy feet making two sharp shocks. ‘Don’t you want yours?’ he asked.

He was the youngest, and they must all try to protect him. ‘Of course,’ she said. So they opened them together.

The family walked to church, crunching through a fresh fall of snow, the servants tramping behind, stepping in their footprints like King Wenceslas’s page. The congregation was smaller than usual for Christmas morning. Perhaps the snow had kept people at home. And there were no bells to remind the slugabeds: the rector had ordered them silenced when the war began, and since then, most of the ringers had volunteered or been called up. But the joyful sound of the bells ringing the Christmas carillon across the snowy fields was sorely missed.

The rector gave a thoughtful sermon, speaking of the losses that had hit every household, the pain that would be mitigated only by their collective determination to defeat the foe and rid the world of this modern evil. He didn’t say, as he had always said in the early days of the war, that God would comfort them in their grief, and the omission interested Sadie, though she couldn’t decide what it signified. Had he stopped believing in God? Had they all? The suffering of the war seemed so horribly man-made, it was hard to think of anything outside it. Why were they fighting? What did it all mean? Of course she knew they had to fight to stop the Germans – but why were the Germans fighting? It didn’t make any sense.

Perhaps that was why the rector didn’t mention God, and why fewer people had come to the service. Nothing made sense any more. The certainties of the old world seemed now like dust that the wind of war had simply blown away. Where was Bobby? His body was rotting in the cold clay of France, but where was he? She couldn’t believe any more in a Heaven of angels and harps, or the smiling dead beckoning you across the river. Or in God as a benign old gentleman with a long white beard. If there was a God – and she suspected there was – it was a God of a distinctly more challenging aspect. A God you would not dare to look in the face.

She supposed they all still prayed when danger threatened, in the ‘God help me! God keep my people safe!’ manner – after all, what else could you do? But did they any more believe that it worked?

Bobby had always been their Master of the Revels, planning their games and keeping the fun going. Without him, everything was flat. Diana, six months married, was spending Christmas with her husband in London; and in the end, David didn’t leave his room. Everyone had assumed he would: they had been working towards it, his first trip downstairs, something to celebrate. But he sat by the fireside in his sitting-room upstairs, staring at the flames, his gramophone playing the same few songs over and over – the sad ones. Among the presents waiting for him under the Christmas tree were some new disc recordings – everyone would be glad to be spared ‘The Last Rose of Summer’ and ‘Un Bel Di’ yet again – but he would not be tempted down.

‘I can’t manage the stairs,’ he said, and, ‘My leg hurts too much.’ That was always the clinching argument; but, seeing William’s and Peter’s disappointment, Sadie managed to get a little bit angry with him.

‘You have to try,’ she said. ‘You’ll never get better if you don’t try.’ And, eventually, ‘You’re spoiling it for everyone.’

But David wouldn’t even be provoked. He gave her that silent, flat stare, then turned his head away. ‘Leave me alone,’ he said.

So it was just the five of them. They took David’s presents up to his room but he only pretended to be interested in them, and eventually he asked them to go, saying he felt tired. He had Christmas dinner in his room, leaving two spaces at the dining-table, his and Bobby’s, that felt like pulled teeth. You didn’t want to look at them, but they drew the eye, as the painful hollow drew the tip of the tongue.

William was wearing Bobby’s wrist-watch, which the War Office had sent back and which Father had given to him. The sight of it made Sadie want to cry. When they left the table she made them all play a game, as Bobby would have. They went along with it, even Mother and Father, for Peter’s sake. But they were pretending, just as David had been.

There were no Christmas celebrations at Dene Park. Northcote natives were disappointed, having hoped that since a local girl, Diana Hunter, had married the heir, Lord Dene, there would be livelier times in prospect, and a boost to Northcote trade. The Earl and Countess Wroughton were spending Christmas at Sandringham again. Royal Christmases were notoriously dull, but the countess had never let personal feelings interfere with duty, and since the King and Queen had invited them, it was their duty to go.

Lord and Lady Dene were spending Christmas in their new home at Park Place. London was lively, with lots of officers on leave, and many families staying up so that their loved ones need not waste precious time travelling. Rupert’s determination was to have the liveliest parties in Town, and the younger set seemed happy to help him achieve it.

Diana was heavily pregnant, expecting her first child in March. She felt huge and ungainly; and she had an uneasy feeling that pregnant women were not supposed to go about in public. Surely it wasn’t the done thing.

‘I don’t want people to see me like this,’ she told Rupert.

‘But, darling, you look wonderful! Magnificently fecund,’ he said, catching her hands and stretching them out to survey her. She really did seem awfully large in her loose breakfast gown. Like a very well-dressed seal. He increased the warmth of his smile. ‘And more beautiful than ever. Really, it’s an unkindness to other women for you to be seen beside them, but I can bear it if you can.’

She was only half placated. She wasn’t sure what ‘fecund’ meant but it didn’t sound proper. And she was beginning to suspect that her husband didn’t mind what means he used, as long as he got his own way. ‘I am in mourning, you know,’ she said.

‘Nobody does mourning any more.’ His mobile features changed rapidly from glee to solemnity. ‘It isn’t patriotic in time of war. Everyone’s lost someone, but we just have to carry on. Can’t have spies telling Fritz we’ve lost heart. The more we eat, drink and make merry, the worse it makes the enemy feel. It’s our duty to have as much fun as possible.’ Diana looked at him doubtfully, and he added, ‘I’ve lost a brother too, you know.’

There was nothing she could say to that. He saw that she had yielded, and pressed home his advantage. ‘I know you get tired, darling, and when you’ve had enough you can make your excuses. But you must be seen on my arm. I don’t want anyone to think my wife lacks pluck.’

Diana felt uncomfortable about her shape, but fortunately the tubular style of the pre-war days was going out and fashions were favouring fuller skirts and long tunic tops, which made concealment easier. There was no shortage of money for clothes – Rupert positively encouraged her to be always buying. And he had proved unexpectedly knowledgeable about corsets.

Before her marriage she had rarely given them a thought, happy simply to buy a basic ‘8s. 11d. small’ from Whiteleys. But Rupert had raised his eyebrows at that. He had sent her to an expert at Marshall and Snelgrove’s, and had thought 15s. 11d. a perfectly reasonable price for white coutil trimmed with silk Swiss embroidery. It had embarrassed her at first to have him know about her undergarments, but after a while she had found it rather exciting, a little warm secret they shared that set them apart from the world.

Pregnancy, however, seemed to require even more from a foundation garment, and he had directed her to an obscure place in Leicester Square to have an adjustable corset made to measure. ‘You must have the proper support, darling,’ he had told her, when she had murmured that three guineas seemed an awful lot to spend on one set of stays. ‘It’s a small price to pay for the well-being of our son and heir.’ In the end he had insisted she have two made, so that she would always have one to wear while the other was being cleaned – he was a stickler for cleanliness. With a bill for six guineas winging its way towards him, she could only hope that she would not let the side down by producing a girl.

In the end, she did enjoy the Christmas season, though she found the endless fun tiring and generally had to excuse herself early. But Rupert was running with a different pack, these days. Before their marriage he had favoured a rather Bohemian set, and she had found some of his friends distinctly odd. Now he seemed to have reverted to the circle of his own class and connections, people he had known all his life. Diana didn’t always like them, but at least they were understandable. What she liked best was when they entertained at home, with a quiet dinner for a dozen old friends. Then she found she could relax and enjoy herself, and didn’t always long for her bed at nine o’clock.

She did miss her family, though. There was never time to go over to Northcote. She felt guilty that they must be having such a sad, quiet Christmas, while she was surrounded by cheerful company. The best she could do was to send a telegram of greeting on Christmas Day, and to order a basket of hothouse fruit to be delivered from Dene Park, with her love.

‘You must persuade your father to have the telephone put in,’ Rupert told her. ‘It really is shockingly medieval that he hasn’t got it. If he had the telephone, you could have rung up on Christmas morning and spoken to everybody, which would be practically as good as visiting them.’

Diana had found it an intriguing thought, that one might use the telephone for ‘chatting’ rather than for communicating essential information as concisely as possible. Only Rupert, she felt sure, could have come up with such an expansive idea.

David was having a nightmare. Ethel, now sick-room maid, had the next room to his, and always slept with her door ajar in case he needed her, so she was with him before his screams reached full pitch. He was sitting up, clawing at his face. She hurried to him, leaned over and grabbed his wrists to stop him hurting himself, but he was strong in the arms and knocked her flying. The tumbler on his bedside table went flying too, and the sound of breaking glass penetrated his clouds. His eyes opened.

‘Wake up,’ she said firmly and calmly, getting to her feet. ‘You’re dreaming. Wake up.’

He was staring blankly, and making ‘Uh? Whu?’ sounds. There were tears on his face, and he had scratched his nose and one cheek, and drawn blood.

‘It was only a dream,’ Ethel said. ‘You’re safe at home. It’s all right.’

‘Lice,’ he said, with a look of horror. ‘There were lice. Oh, the stink!’ His hands flailed, making brushing-off movements.

But she saw he was coming back. ‘No lice. No stink,’ she said. She helped him to sit up more, punched his pillows, straightened his bedclothes. ‘Just lovely clean sheets, smelling of lavender. Smell – go on. See? Lavender. You’re home.’

He gave a long look round, and drew a shuddering sigh. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘Go back to bed.’

‘I’m up now,’ she said briskly. She fetched a damp flannel, wiped his face and inspected the scratches, which were only shallow. He had been sweating, despite the cold of the night, so she rinsed the flannel and wiped his neck and his upper body inside his pyjama jacket. He allowed her ministrations, passive now. ‘Is your leg hurting?’ she asked. He nodded. ‘Do you want something?’

‘No morphine,’ he said. He was terrified that if he took too much, it would lose its power.

‘I’ll make you up some Collis Browne’s,’ she said. ‘That always soothes you.’

The small dark bottle of Dr Collis Browne’s tincture stood with the others on his medicine table, and she mixed him a dose in his tooth-mug. When he had drunk it, she picked up the bits of broken glass and said, ‘You just rest quietly, and I’ll go down to the kitchen and make you some Horlicks. Do you want me to call anyone?’

‘No,’ he said. He tried to smile at her, but his mouth wouldn’t obey him. ‘You’re all I need,’ he said. ‘Thank you.’

She nodded, pleased, and went away.

He leaned back against his pillows, feeling himself trembling lightly. Sadie always said if you had a bad dream, you had to go through it in your head when you were properly awake, to recognise that it was untrue, and banish it. He couldn’t remember how it had started, only a confusion of noises and voices. The war again – always the war. Only the end bit was vivid. He’d been lying down, in bed somewhere, and the lice had begun crawling up from under the covers and over his face. And when he had lifted the bedclothes and looked inside, the whole bed had been full of them, millions of them, a seething mass covering his body. That was when he had started screaming.

No, he had started screaming when he had seen that, under the lice, he had no legs. Not even stumps. His body ended with his trunk, and beyond that there was just a heaving, pullulating infinity of lice.

He shuddered, swallowed, finding his mouth dry, and tried to shake off the horror, looking round his familiar room, thanking God for electric light, which did not make moving shadows to torment you, like the candle stubs they relied on in the dugouts. It was only imagination, he knew, but he could still smell that smell. Trench mud. It had a stink all its own – once known never forgotten, they used to joke. In his dream it was he who smelt like that. The stink seeped out of his pores. They brought it with them when they came out of the line, had all been morbidly conscious of it until they got to a proper bath and carbolic soap. But the memory of it haunted him. Sometimes he felt he would never get rid of it, that when people came near him they would catch its whiff and be repelled. Another reason he did not want to see people.

He was awake now, and the familiar depression had sunk back to its accustomed place. Some people spoke of it as a black dog that followed you, or a raven that perched on your shoulder, but to him it was like a boulder that rested on his chest and made it hard to breathe. It filled his view: he could not see past it.

He thought of his younger self, remembered how he had sat beneath the trees in the summer of 1914 with his best friend Oliphant, how they had talked of wanting to do something noble. The war had seemed to offer endless possibilities of shining heroism. They had dreamed of glory, even of honourable death. What fools they had been! There was nothing honourable about death, just filthy, stinking rags of flesh trodden into the mud and forgotten. There was no glory in war, just pain and horror and degradation.

Bobby had gone to war, cheerful, handsome Bobby, whom everybody loved, and Bobby was dead. Well, at least he was a hero. David had achieved nothing. His name would not go down in history. He had gone to war and come back a wreck, a hopeless cripple; he would never walk again, never live a normal life. He had no future but pain and dependency.

He felt as though he was in a dugout after a shell explosion: the roof had collapsed and the entrance had fallen in. He was trapped, buried alive – but no-one knew he was there. He could hear them outside, moving about, talking, living their lives, but no-one could hear him screaming. Buried alive. It was a joke, wasn’t it? A hideous joke. Like his leg, which throbbed like a rotten tooth. How much trouble had the doctors gone to, to save it? That was a joke, too.

Ethel came back with the mug of Horlicks, and a fresh glass of water for his bedside table. He took the mug from her and said, ‘Thanks. You can go back to bed now.’

But she had brought some sewing in with her, and sat down with it in the armchair by the window. ‘That’s all right. I’ve got this shirt to do. I’ll sit here until you drop off again,’ she said.

He didn’t want to feel grateful. He told himself roughly that it was her job, she was paid to be the sick-room maid – and that was another joke, wasn’t it? He, David Hunter, inhabitant of a sick-room.

He sipped the Horlicks, and the familiar taste was soothing. And the Collis Browne’s was warming away his cold dreads. ‘What time is it?’ he asked.

‘Half past three,’ Ethel said, turning the shirt to find the tear.

William’s, David thought. Too big to be Peter’s. His brothers, alive and well, free to come and go, to plan for their futures, to be normal and useful and whole. Tears pushed up to the back of his nose, and he fought them down, sipped more Horlicks.

‘Plenty of time to get back to sleep,’ Ethel said, without looking up.

And he thought that, when he had finished the drink, he probably would, with her there to guard him. He watched her sewing, and knew she would not speak unless he did. She knew the value of silence. Or perhaps she just knew her place. But he was glad she was there. Wasn’t that pathetic? He was glad the sick-room maid was there.

Edward had felt guiltily glad to be going back to work. He had known it would be a sad Christmas without Bobby, but he had pinned his hopes on David coming downstairs. Sister Heaton, who had looked after him for the first few weeks at home, had been very firm that he must aim for that, and he had seemed to improve under her stimulating briskness. Now she was gone, he seemed to be sinking into a Slough of Despond. Edward did not know what to do to reach him, and it troubled him to feel so helpless. At least at the bank he knew what to do; at least there problems had solutions.

When he went down to breakfast, he was surprised to find Beattie, dressed to go out.

He’d been sleeping in the dressing-room for some time now. From the beginning of the war, she had been withdrawing from him; and the consecutive blows of Bobby’s death and David’s wounding seemed to have shattered the delicate web of connections between them. When she looked at him, her eyes passed over him blankly, as if he were a stranger. It was worse in its way than his inability to help David, for it meant that each of them had to bear their grief alone.

To pretend that things were normal seemed to be all that was left to do, so he said, ‘Good morning, my dear. You’re up early.’

‘I’m going up to Town,’ she said, sipping coffee.

He poured himself some. It seemed distressingly weak. ‘I wish you would speak to Cook about the coffee,’ he said.

‘Williamson’s couldn’t fill the last order,’ said Beattie. ‘We only had a little left, so I told her to make it last.’

‘I’d sooner have it less often, and have it strong,’ he said. In some places, he’d heard, they were eking out coffee with ground acorns, or the French subterfuge, chicory root. The notion made him shudder. What was civilisation, if a man could not have a proper cup of coffee at breakfast time? ‘I will do without coffee after dinner, if necessary.’

‘I’ll tell her,’ said Beattie. She still had not looked at him.

‘What takes you to Town?’ he asked carefully.

Now she looked up, but her eyes did not meet his. ‘The canteen. There are soldiers on leave, coming and going. And I thought I would call on Diana. It was her first Christmas away from us. I did hope they would at least drop in,’ she added.

‘I expect the snow put them off,’ Edward said. ‘Driving would have been difficult.’

‘The trains were running,’ Beattie pointed out.

It made Edward smile. ‘I can’t imagine our son-in-law travelling all this way on the Metropolitan Line – not now he’s Lord Dene.’

That did at least attract her attention. ‘It’s so strange that she’s Lady Dene, when we thought all that was over and done with.’ Diana had been engaged to Rupert’s older brother, Charles, but he had fallen in France.

Edward said, ‘I admit I was worried when she accepted Rupert. It seemed too hasty – perhaps a wartime thing. But they seem happy enough. If the magazines are anything to go by, they are seen everywhere together.’

‘I think she’s outgrown Northcote,’ Beattie said. ‘London’s her playground now.’

Ada came in with the tray. Cook appeared on her heels. ‘If you was going up to Town, madam, and happened to be passing any shops . . .’ she began wheedlingly.

‘What is it that you want?’ Beattie asked.

‘Well, madam . . .’ She hesitated.

‘Coffee?’ Edward suggested, with faint acerbity.

‘Oh, no, sir. There was a message came with Williamson’s boy just now,’ she replied. ‘They’re getting some in today, and they’ll send it up later.’

‘What, then?’ Beattie asked impatiently.

Cook took the plunge. ‘Suet, madam,’ she blurted.

‘Suet?’ Beattie’s eyebrows shot up. ‘You can’t expect me to walk about London clutching a lump of suet.’

‘Oh, no madam, perish the thought! They do it ready prepared now, shredded, in nice clean cardboard boxes. Just if you was to happen to pass a grocery shop, and it wasn’t any trouble . . .’

Beattie sighed. ‘Very well. How much?’

‘As many as they’ll let you have, madam – or as many as is convenient to carry,’ said Cook, humbly. ‘You just never know what’s going to go missing in shops nowadays. There doesn’t seem to be no sense to it. Only the other day—’

‘Thank you, Cook,’ Beattie interrupted firmly. ‘I’ll see what I can do.’

‘Very good, madam.’ Cook knew herself dismissed, and turned away, but she could not suppress the sotto voce grumbling, any more than a volcano could. ‘I don’t know what things are coming to. No coffee, tea as dear as gold dust. And that boy of theirs! Whistling at the back door, same as if I was a dog! “Keep yer hair on, Ma,” he says. Twelve years old, and he calls me “Ma”. Me! Never in all my born days . . .’ She mumbled her way out of the morning-room.

Edward regarded his wife with mock admiration. ‘I didn’t realise until now the trials you have to bear as a housewife. I tip my hat to you.’

In the old days she would have laughed, and a conversation would have bloomed between them. Now, however, she just looked distracted, as though he had called her from important thoughts. ‘Have you any message for Diana?’ she asked at length. He couldn’t help feeling that that was not what she had been thinking.

‘Just my love,’ Edward said. ‘And I hope we’ll see her soon.’

The door at Park Place was opened by a middle-aged man in livery. Male servants were getting ever harder to come by, thanks to conscription, but Beattie noted the man had a slight limp, which might explain his presence. He seemed to know his business, anyway, looking at her with the polite blankness of a well-trained servant.

‘I do not believe her ladyship has left her room yet, madam,’ he replied, to Beattie’s query, ‘but if you would care to step in I will enquire for you.’

Her ladyship, Beattie thought. Her little Diana was now her ladyship. And she lived in a grand house in St James’s and had a footman to answer the door. The fulfilment of her youthful dreams. Beattie hoped it answered. At least when the war was over she would still have all this, however her marriage turned out.

The house was bright and smart and smelt of newness and fresh paint. There were flowers in a vase on a stand, the hall table gleamed with polish and the big looking-glass behind it sparkled. Her daughter had good servants.

The footman had gone upstairs, but it was a woman who came down, in the plain black dress of a personal maid. ‘Her ladyship will be glad to see you, madam, if you don’t mind her being undressed. She’s still in bed.’

Diana was sitting up against a mound of pillows, in a bed-jacket of some kind that was a froth of lace and chiffon. Her hair looked sweetly ruffled, her face was glowing with health, and the bedclothes only partly concealed the bulge of the baby.

She smiled at her mother. ‘How lovely to see you! But you’re so early – is everything all right?’

‘I had to come up to Town, so I thought I’d call. You have a new maid,’ she commented, as the door closed behind her.

‘Yes. Padmore. She’s much better. I never liked the one Lady Wroughton chose for me.’

Beattie wondered how Diana’s autocratic mother-in-law had liked having her choice superseded. ‘Are you well?’ she asked.

‘Oh, quite! Rupert says I should rest as much as possible, that’s all. There’s never anything to do in the mornings anyway, so I just stay in bed. Isn’t that dreadful?’

‘It’s very wise.’

‘How is everyone? I missed you all at Christmas. How was it?’

‘Quiet. Thank you for the fruit, by the way,’ Beattie said.

‘They have all sorts of fruit at Dene, and there was no-one there to eat it. But afterwards I thought it must have looked odd. You weren’t offended?’

Beattie laughed. ‘Not at all. Hothouse fruit is always acceptable. We were sorry not to see you, but we understood.’

‘I hoped you would,’ Diana said. ‘I’m so uncomfortable sitting in a car, except for a short journey. And then, with the snow and everything . . . Really, I wouldn’t go out at all, except that Rupert insists on having me with him. But I wished I could have visited you.’

‘It doesn’t matter, darling, as long as you’re happy,’ Beattie said. ‘You are happy, aren’t you?’

‘Oh, yes. Rupert’s so sweet to me. I just wish this baby would hurry up and come, so I can see it. Didn’t you think it strange, when you were in my condition, that you didn’t know what it looked like?’

‘It’s too long ago. I can’t remember,’ Beattie said. But of course she remembered. David, her firstborn, her dearest – she remembered everything about it.

Diana read her face. ‘How is David? Did he come downstairs?’

Beattie shook her head. ‘He’s very low. But it was a hard time for all of us.’

‘Our first Christmas without Bobby. I can’t believe he’s gone.’

‘Try not to think about it,’ Beattie said. ‘You should have nothing but happy thoughts, until the baby comes.’

‘Does it really make a difference?’

‘They say it does, so better to be on the safe side.’ She stood up. ‘Now I shall go and leave you in peace. I’ve lots to do.’

‘What sort of things?’ Diana asked.

Beattie chose a safe one. ‘Cook’s run out of suet, and Williamson’s don’t have any, so I’m to look for some if I pass any shops.’

‘I’m sure we must have some downstairs. I’ll ring for Padmore.’

‘No, no! What would she think, if you sent her for suet?’ Beattie said, smiling.

‘Rupert says we ought to challenge the servants every now and then, to stop them taking things for granted. He says once they start anticipating you, they think they control you.’

‘Your husband does have novel ideas!’ She rose and kissed her daughter’s cheek. ‘I must be off. I’m glad to see you looking so bonny,’ she said.

In the time between Christmas and New Year, Edward traditionally reviewed his clients’ portfolios, and looked into new investment opportunities. It was usually a quiet period, with Parliament in recess and most of his clients out of Town. But the war had changed many things. Weather was too bad at the Front for anything oth

‘What is it?’ she asked.

‘It’s Christmas,’ he said.

Beyond Peter’s back, the house was in darkness. If the servants had been up there would have been light from the hall below.

‘It’s too early,’ she groaned. ‘Go back to bed.’ It was bitterly cold, too. Peter, in his pyjamas, was shivering, shifting from foot to foot. ‘Hasn’t Father Christmas been?’ she asked.

‘I know it isn’t Father Christmas,’ he said. ‘I know it’s Mum and Dad.’ He was ten years old, and the war had been going on for more than two of those. Childhood was different, these days. Illusions were harder to hold on to.

‘What’s the matter, then?’ she asked.

He was silent a moment, then said mournfully, ‘It doesn’t seem a bit like Christmas.’

She softened. ‘Do you want to bring your stocking in here? Don’t make a noise, though.’

He scampered away. She put on her bedside lamp, and reached for her dressing-gown, which she had spread across the bed for extra warmth, to put it on. Nailer had been curled under it, across the foot of the bed. He lifted an enquiring head, then lowered it again, sticking his nose back under his belly like a cat. Down in the hall, the Vienna clock struck a slow, thoughtful five. Her own stocking was hanging on one of the bed-knobs, but she could happily have waited until morning for it. She was too old for a stocking, really – she would be nineteen in a few weeks’ time – but she knew her parents were making an effort to keep Christmas as much like itself as possible, for all their sakes.

But Bobby was dead – the realisation hit her all over again, with astonishment and pain, as it did almost every day on waking. And David had been wounded, invalided out of the army, and who knew if he would ever walk properly again? Peter was right: it didn’t seem a bit like Christmas.

He came back with his stocking and jumped into bed with her, his icy feet making two sharp shocks. ‘Don’t you want yours?’ he asked.

He was the youngest, and they must all try to protect him. ‘Of course,’ she said. So they opened them together.

The family walked to church, crunching through a fresh fall of snow, the servants tramping behind, stepping in their footprints like King Wenceslas’s page. The congregation was smaller than usual for Christmas morning. Perhaps the snow had kept people at home. And there were no bells to remind the slugabeds: the rector had ordered them silenced when the war began, and since then, most of the ringers had volunteered or been called up. But the joyful sound of the bells ringing the Christmas carillon across the snowy fields was sorely missed.

The rector gave a thoughtful sermon, speaking of the losses that had hit every household, the pain that would be mitigated only by their collective determination to defeat the foe and rid the world of this modern evil. He didn’t say, as he had always said in the early days of the war, that God would comfort them in their grief, and the omission interested Sadie, though she couldn’t decide what it signified. Had he stopped believing in God? Had they all? The suffering of the war seemed so horribly man-made, it was hard to think of anything outside it. Why were they fighting? What did it all mean? Of course she knew they had to fight to stop the Germans – but why were the Germans fighting? It didn’t make any sense.

Perhaps that was why the rector didn’t mention God, and why fewer people had come to the service. Nothing made sense any more. The certainties of the old world seemed now like dust that the wind of war had simply blown away. Where was Bobby? His body was rotting in the cold clay of France, but where was he? She couldn’t believe any more in a Heaven of angels and harps, or the smiling dead beckoning you across the river. Or in God as a benign old gentleman with a long white beard. If there was a God – and she suspected there was – it was a God of a distinctly more challenging aspect. A God you would not dare to look in the face.

She supposed they all still prayed when danger threatened, in the ‘God help me! God keep my people safe!’ manner – after all, what else could you do? But did they any more believe that it worked?

Bobby had always been their Master of the Revels, planning their games and keeping the fun going. Without him, everything was flat. Diana, six months married, was spending Christmas with her husband in London; and in the end, David didn’t leave his room. Everyone had assumed he would: they had been working towards it, his first trip downstairs, something to celebrate. But he sat by the fireside in his sitting-room upstairs, staring at the flames, his gramophone playing the same few songs over and over – the sad ones. Among the presents waiting for him under the Christmas tree were some new disc recordings – everyone would be glad to be spared ‘The Last Rose of Summer’ and ‘Un Bel Di’ yet again – but he would not be tempted down.

‘I can’t manage the stairs,’ he said, and, ‘My leg hurts too much.’ That was always the clinching argument; but, seeing William’s and Peter’s disappointment, Sadie managed to get a little bit angry with him.

‘You have to try,’ she said. ‘You’ll never get better if you don’t try.’ And, eventually, ‘You’re spoiling it for everyone.’

But David wouldn’t even be provoked. He gave her that silent, flat stare, then turned his head away. ‘Leave me alone,’ he said.

So it was just the five of them. They took David’s presents up to his room but he only pretended to be interested in them, and eventually he asked them to go, saying he felt tired. He had Christmas dinner in his room, leaving two spaces at the dining-table, his and Bobby’s, that felt like pulled teeth. You didn’t want to look at them, but they drew the eye, as the painful hollow drew the tip of the tongue.

William was wearing Bobby’s wrist-watch, which the War Office had sent back and which Father had given to him. The sight of it made Sadie want to cry. When they left the table she made them all play a game, as Bobby would have. They went along with it, even Mother and Father, for Peter’s sake. But they were pretending, just as David had been.

There were no Christmas celebrations at Dene Park. Northcote natives were disappointed, having hoped that since a local girl, Diana Hunter, had married the heir, Lord Dene, there would be livelier times in prospect, and a boost to Northcote trade. The Earl and Countess Wroughton were spending Christmas at Sandringham again. Royal Christmases were notoriously dull, but the countess had never let personal feelings interfere with duty, and since the King and Queen had invited them, it was their duty to go.

Lord and Lady Dene were spending Christmas in their new home at Park Place. London was lively, with lots of officers on leave, and many families staying up so that their loved ones need not waste precious time travelling. Rupert’s determination was to have the liveliest parties in Town, and the younger set seemed happy to help him achieve it.

Diana was heavily pregnant, expecting her first child in March. She felt huge and ungainly; and she had an uneasy feeling that pregnant women were not supposed to go about in public. Surely it wasn’t the done thing.

‘I don’t want people to see me like this,’ she told Rupert.

‘But, darling, you look wonderful! Magnificently fecund,’ he said, catching her hands and stretching them out to survey her. She really did seem awfully large in her loose breakfast gown. Like a very well-dressed seal. He increased the warmth of his smile. ‘And more beautiful than ever. Really, it’s an unkindness to other women for you to be seen beside them, but I can bear it if you can.’

She was only half placated. She wasn’t sure what ‘fecund’ meant but it didn’t sound proper. And she was beginning to suspect that her husband didn’t mind what means he used, as long as he got his own way. ‘I am in mourning, you know,’ she said.

‘Nobody does mourning any more.’ His mobile features changed rapidly from glee to solemnity. ‘It isn’t patriotic in time of war. Everyone’s lost someone, but we just have to carry on. Can’t have spies telling Fritz we’ve lost heart. The more we eat, drink and make merry, the worse it makes the enemy feel. It’s our duty to have as much fun as possible.’ Diana looked at him doubtfully, and he added, ‘I’ve lost a brother too, you know.’

There was nothing she could say to that. He saw that she had yielded, and pressed home his advantage. ‘I know you get tired, darling, and when you’ve had enough you can make your excuses. But you must be seen on my arm. I don’t want anyone to think my wife lacks pluck.’

Diana felt uncomfortable about her shape, but fortunately the tubular style of the pre-war days was going out and fashions were favouring fuller skirts and long tunic tops, which made concealment easier. There was no shortage of money for clothes – Rupert positively encouraged her to be always buying. And he had proved unexpectedly knowledgeable about corsets.

Before her marriage she had rarely given them a thought, happy simply to buy a basic ‘8s. 11d. small’ from Whiteleys. But Rupert had raised his eyebrows at that. He had sent her to an expert at Marshall and Snelgrove’s, and had thought 15s. 11d. a perfectly reasonable price for white coutil trimmed with silk Swiss embroidery. It had embarrassed her at first to have him know about her undergarments, but after a while she had found it rather exciting, a little warm secret they shared that set them apart from the world.

Pregnancy, however, seemed to require even more from a foundation garment, and he had directed her to an obscure place in Leicester Square to have an adjustable corset made to measure. ‘You must have the proper support, darling,’ he had told her, when she had murmured that three guineas seemed an awful lot to spend on one set of stays. ‘It’s a small price to pay for the well-being of our son and heir.’ In the end he had insisted she have two made, so that she would always have one to wear while the other was being cleaned – he was a stickler for cleanliness. With a bill for six guineas winging its way towards him, she could only hope that she would not let the side down by producing a girl.

In the end, she did enjoy the Christmas season, though she found the endless fun tiring and generally had to excuse herself early. But Rupert was running with a different pack, these days. Before their marriage he had favoured a rather Bohemian set, and she had found some of his friends distinctly odd. Now he seemed to have reverted to the circle of his own class and connections, people he had known all his life. Diana didn’t always like them, but at least they were understandable. What she liked best was when they entertained at home, with a quiet dinner for a dozen old friends. Then she found she could relax and enjoy herself, and didn’t always long for her bed at nine o’clock.

She did miss her family, though. There was never time to go over to Northcote. She felt guilty that they must be having such a sad, quiet Christmas, while she was surrounded by cheerful company. The best she could do was to send a telegram of greeting on Christmas Day, and to order a basket of hothouse fruit to be delivered from Dene Park, with her love.

‘You must persuade your father to have the telephone put in,’ Rupert told her. ‘It really is shockingly medieval that he hasn’t got it. If he had the telephone, you could have rung up on Christmas morning and spoken to everybody, which would be practically as good as visiting them.’

Diana had found it an intriguing thought, that one might use the telephone for ‘chatting’ rather than for communicating essential information as concisely as possible. Only Rupert, she felt sure, could have come up with such an expansive idea.

David was having a nightmare. Ethel, now sick-room maid, had the next room to his, and always slept with her door ajar in case he needed her, so she was with him before his screams reached full pitch. He was sitting up, clawing at his face. She hurried to him, leaned over and grabbed his wrists to stop him hurting himself, but he was strong in the arms and knocked her flying. The tumbler on his bedside table went flying too, and the sound of breaking glass penetrated his clouds. His eyes opened.

‘Wake up,’ she said firmly and calmly, getting to her feet. ‘You’re dreaming. Wake up.’

He was staring blankly, and making ‘Uh? Whu?’ sounds. There were tears on his face, and he had scratched his nose and one cheek, and drawn blood.

‘It was only a dream,’ Ethel said. ‘You’re safe at home. It’s all right.’

‘Lice,’ he said, with a look of horror. ‘There were lice. Oh, the stink!’ His hands flailed, making brushing-off movements.

But she saw he was coming back. ‘No lice. No stink,’ she said. She helped him to sit up more, punched his pillows, straightened his bedclothes. ‘Just lovely clean sheets, smelling of lavender. Smell – go on. See? Lavender. You’re home.’

He gave a long look round, and drew a shuddering sigh. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘Go back to bed.’

‘I’m up now,’ she said briskly. She fetched a damp flannel, wiped his face and inspected the scratches, which were only shallow. He had been sweating, despite the cold of the night, so she rinsed the flannel and wiped his neck and his upper body inside his pyjama jacket. He allowed her ministrations, passive now. ‘Is your leg hurting?’ she asked. He nodded. ‘Do you want something?’

‘No morphine,’ he said. He was terrified that if he took too much, it would lose its power.

‘I’ll make you up some Collis Browne’s,’ she said. ‘That always soothes you.’

The small dark bottle of Dr Collis Browne’s tincture stood with the others on his medicine table, and she mixed him a dose in his tooth-mug. When he had drunk it, she picked up the bits of broken glass and said, ‘You just rest quietly, and I’ll go down to the kitchen and make you some Horlicks. Do you want me to call anyone?’

‘No,’ he said. He tried to smile at her, but his mouth wouldn’t obey him. ‘You’re all I need,’ he said. ‘Thank you.’

She nodded, pleased, and went away.

He leaned back against his pillows, feeling himself trembling lightly. Sadie always said if you had a bad dream, you had to go through it in your head when you were properly awake, to recognise that it was untrue, and banish it. He couldn’t remember how it had started, only a confusion of noises and voices. The war again – always the war. Only the end bit was vivid. He’d been lying down, in bed somewhere, and the lice had begun crawling up from under the covers and over his face. And when he had lifted the bedclothes and looked inside, the whole bed had been full of them, millions of them, a seething mass covering his body. That was when he had started screaming.

No, he had started screaming when he had seen that, under the lice, he had no legs. Not even stumps. His body ended with his trunk, and beyond that there was just a heaving, pullulating infinity of lice.

He shuddered, swallowed, finding his mouth dry, and tried to shake off the horror, looking round his familiar room, thanking God for electric light, which did not make moving shadows to torment you, like the candle stubs they relied on in the dugouts. It was only imagination, he knew, but he could still smell that smell. Trench mud. It had a stink all its own – once known never forgotten, they used to joke. In his dream it was he who smelt like that. The stink seeped out of his pores. They brought it with them when they came out of the line, had all been morbidly conscious of it until they got to a proper bath and carbolic soap. But the memory of it haunted him. Sometimes he felt he would never get rid of it, that when people came near him they would catch its whiff and be repelled. Another reason he did not want to see people.

He was awake now, and the familiar depression had sunk back to its accustomed place. Some people spoke of it as a black dog that followed you, or a raven that perched on your shoulder, but to him it was like a boulder that rested on his chest and made it hard to breathe. It filled his view: he could not see past it.

He thought of his younger self, remembered how he had sat beneath the trees in the summer of 1914 with his best friend Oliphant, how they had talked of wanting to do something noble. The war had seemed to offer endless possibilities of shining heroism. They had dreamed of glory, even of honourable death. What fools they had been! There was nothing honourable about death, just filthy, stinking rags of flesh trodden into the mud and forgotten. There was no glory in war, just pain and horror and degradation.

Bobby had gone to war, cheerful, handsome Bobby, whom everybody loved, and Bobby was dead. Well, at least he was a hero. David had achieved nothing. His name would not go down in history. He had gone to war and come back a wreck, a hopeless cripple; he would never walk again, never live a normal life. He had no future but pain and dependency.

He felt as though he was in a dugout after a shell explosion: the roof had collapsed and the entrance had fallen in. He was trapped, buried alive – but no-one knew he was there. He could hear them outside, moving about, talking, living their lives, but no-one could hear him screaming. Buried alive. It was a joke, wasn’t it? A hideous joke. Like his leg, which throbbed like a rotten tooth. How much trouble had the doctors gone to, to save it? That was a joke, too.

Ethel came back with the mug of Horlicks, and a fresh glass of water for his bedside table. He took the mug from her and said, ‘Thanks. You can go back to bed now.’

But she had brought some sewing in with her, and sat down with it in the armchair by the window. ‘That’s all right. I’ve got this shirt to do. I’ll sit here until you drop off again,’ she said.

He didn’t want to feel grateful. He told himself roughly that it was her job, she was paid to be the sick-room maid – and that was another joke, wasn’t it? He, David Hunter, inhabitant of a sick-room.

He sipped the Horlicks, and the familiar taste was soothing. And the Collis Browne’s was warming away his cold dreads. ‘What time is it?’ he asked.

‘Half past three,’ Ethel said, turning the shirt to find the tear.

William’s, David thought. Too big to be Peter’s. His brothers, alive and well, free to come and go, to plan for their futures, to be normal and useful and whole. Tears pushed up to the back of his nose, and he fought them down, sipped more Horlicks.

‘Plenty of time to get back to sleep,’ Ethel said, without looking up.

And he thought that, when he had finished the drink, he probably would, with her there to guard him. He watched her sewing, and knew she would not speak unless he did. She knew the value of silence. Or perhaps she just knew her place. But he was glad she was there. Wasn’t that pathetic? He was glad the sick-room maid was there.

Edward had felt guiltily glad to be going back to work. He had known it would be a sad Christmas without Bobby, but he had pinned his hopes on David coming downstairs. Sister Heaton, who had looked after him for the first few weeks at home, had been very firm that he must aim for that, and he had seemed to improve under her stimulating briskness. Now she was gone, he seemed to be sinking into a Slough of Despond. Edward did not know what to do to reach him, and it troubled him to feel so helpless. At least at the bank he knew what to do; at least there problems had solutions.

When he went down to breakfast, he was surprised to find Beattie, dressed to go out.

He’d been sleeping in the dressing-room for some time now. From the beginning of the war, she had been withdrawing from him; and the consecutive blows of Bobby’s death and David’s wounding seemed to have shattered the delicate web of connections between them. When she looked at him, her eyes passed over him blankly, as if he were a stranger. It was worse in its way than his inability to help David, for it meant that each of them had to bear their grief alone.

To pretend that things were normal seemed to be all that was left to do, so he said, ‘Good morning, my dear. You’re up early.’

‘I’m going up to Town,’ she said, sipping coffee.

He poured himself some. It seemed distressingly weak. ‘I wish you would speak to Cook about the coffee,’ he said.

‘Williamson’s couldn’t fill the last order,’ said Beattie. ‘We only had a little left, so I told her to make it last.’

‘I’d sooner have it less often, and have it strong,’ he said. In some places, he’d heard, they were eking out coffee with ground acorns, or the French subterfuge, chicory root. The notion made him shudder. What was civilisation, if a man could not have a proper cup of coffee at breakfast time? ‘I will do without coffee after dinner, if necessary.’

‘I’ll tell her,’ said Beattie. She still had not looked at him.

‘What takes you to Town?’ he asked carefully.

Now she looked up, but her eyes did not meet his. ‘The canteen. There are soldiers on leave, coming and going. And I thought I would call on Diana. It was her first Christmas away from us. I did hope they would at least drop in,’ she added.

‘I expect the snow put them off,’ Edward said. ‘Driving would have been difficult.’

‘The trains were running,’ Beattie pointed out.

It made Edward smile. ‘I can’t imagine our son-in-law travelling all this way on the Metropolitan Line – not now he’s Lord Dene.’

That did at least attract her attention. ‘It’s so strange that she’s Lady Dene, when we thought all that was over and done with.’ Diana had been engaged to Rupert’s older brother, Charles, but he had fallen in France.

Edward said, ‘I admit I was worried when she accepted Rupert. It seemed too hasty – perhaps a wartime thing. But they seem happy enough. If the magazines are anything to go by, they are seen everywhere together.’

‘I think she’s outgrown Northcote,’ Beattie said. ‘London’s her playground now.’

Ada came in with the tray. Cook appeared on her heels. ‘If you was going up to Town, madam, and happened to be passing any shops . . .’ she began wheedlingly.

‘What is it that you want?’ Beattie asked.

‘Well, madam . . .’ She hesitated.

‘Coffee?’ Edward suggested, with faint acerbity.

‘Oh, no, sir. There was a message came with Williamson’s boy just now,’ she replied. ‘They’re getting some in today, and they’ll send it up later.’

‘What, then?’ Beattie asked impatiently.

Cook took the plunge. ‘Suet, madam,’ she blurted.

‘Suet?’ Beattie’s eyebrows shot up. ‘You can’t expect me to walk about London clutching a lump of suet.’

‘Oh, no madam, perish the thought! They do it ready prepared now, shredded, in nice clean cardboard boxes. Just if you was to happen to pass a grocery shop, and it wasn’t any trouble . . .’

Beattie sighed. ‘Very well. How much?’

‘As many as they’ll let you have, madam – or as many as is convenient to carry,’ said Cook, humbly. ‘You just never know what’s going to go missing in shops nowadays. There doesn’t seem to be no sense to it. Only the other day—’

‘Thank you, Cook,’ Beattie interrupted firmly. ‘I’ll see what I can do.’

‘Very good, madam.’ Cook knew herself dismissed, and turned away, but she could not suppress the sotto voce grumbling, any more than a volcano could. ‘I don’t know what things are coming to. No coffee, tea as dear as gold dust. And that boy of theirs! Whistling at the back door, same as if I was a dog! “Keep yer hair on, Ma,” he says. Twelve years old, and he calls me “Ma”. Me! Never in all my born days . . .’ She mumbled her way out of the morning-room.

Edward regarded his wife with mock admiration. ‘I didn’t realise until now the trials you have to bear as a housewife. I tip my hat to you.’

In the old days she would have laughed, and a conversation would have bloomed between them. Now, however, she just looked distracted, as though he had called her from important thoughts. ‘Have you any message for Diana?’ she asked at length. He couldn’t help feeling that that was not what she had been thinking.

‘Just my love,’ Edward said. ‘And I hope we’ll see her soon.’

The door at Park Place was opened by a middle-aged man in livery. Male servants were getting ever harder to come by, thanks to conscription, but Beattie noted the man had a slight limp, which might explain his presence. He seemed to know his business, anyway, looking at her with the polite blankness of a well-trained servant.

‘I do not believe her ladyship has left her room yet, madam,’ he replied, to Beattie’s query, ‘but if you would care to step in I will enquire for you.’

Her ladyship, Beattie thought. Her little Diana was now her ladyship. And she lived in a grand house in St James’s and had a footman to answer the door. The fulfilment of her youthful dreams. Beattie hoped it answered. At least when the war was over she would still have all this, however her marriage turned out.

The house was bright and smart and smelt of newness and fresh paint. There were flowers in a vase on a stand, the hall table gleamed with polish and the big looking-glass behind it sparkled. Her daughter had good servants.

The footman had gone upstairs, but it was a woman who came down, in the plain black dress of a personal maid. ‘Her ladyship will be glad to see you, madam, if you don’t mind her being undressed. She’s still in bed.’

Diana was sitting up against a mound of pillows, in a bed-jacket of some kind that was a froth of lace and chiffon. Her hair looked sweetly ruffled, her face was glowing with health, and the bedclothes only partly concealed the bulge of the baby.

She smiled at her mother. ‘How lovely to see you! But you’re so early – is everything all right?’

‘I had to come up to Town, so I thought I’d call. You have a new maid,’ she commented, as the door closed behind her.

‘Yes. Padmore. She’s much better. I never liked the one Lady Wroughton chose for me.’

Beattie wondered how Diana’s autocratic mother-in-law had liked having her choice superseded. ‘Are you well?’ she asked.

‘Oh, quite! Rupert says I should rest as much as possible, that’s all. There’s never anything to do in the mornings anyway, so I just stay in bed. Isn’t that dreadful?’

‘It’s very wise.’

‘How is everyone? I missed you all at Christmas. How was it?’

‘Quiet. Thank you for the fruit, by the way,’ Beattie said.

‘They have all sorts of fruit at Dene, and there was no-one there to eat it. But afterwards I thought it must have looked odd. You weren’t offended?’

Beattie laughed. ‘Not at all. Hothouse fruit is always acceptable. We were sorry not to see you, but we understood.’

‘I hoped you would,’ Diana said. ‘I’m so uncomfortable sitting in a car, except for a short journey. And then, with the snow and everything . . . Really, I wouldn’t go out at all, except that Rupert insists on having me with him. But I wished I could have visited you.’

‘It doesn’t matter, darling, as long as you’re happy,’ Beattie said. ‘You are happy, aren’t you?’

‘Oh, yes. Rupert’s so sweet to me. I just wish this baby would hurry up and come, so I can see it. Didn’t you think it strange, when you were in my condition, that you didn’t know what it looked like?’

‘It’s too long ago. I can’t remember,’ Beattie said. But of course she remembered. David, her firstborn, her dearest – she remembered everything about it.

Diana read her face. ‘How is David? Did he come downstairs?’

Beattie shook her head. ‘He’s very low. But it was a hard time for all of us.’

‘Our first Christmas without Bobby. I can’t believe he’s gone.’

‘Try not to think about it,’ Beattie said. ‘You should have nothing but happy thoughts, until the baby comes.’

‘Does it really make a difference?’

‘They say it does, so better to be on the safe side.’ She stood up. ‘Now I shall go and leave you in peace. I’ve lots to do.’

‘What sort of things?’ Diana asked.

Beattie chose a safe one. ‘Cook’s run out of suet, and Williamson’s don’t have any, so I’m to look for some if I pass any shops.’

‘I’m sure we must have some downstairs. I’ll ring for Padmore.’

‘No, no! What would she think, if you sent her for suet?’ Beattie said, smiling.

‘Rupert says we ought to challenge the servants every now and then, to stop them taking things for granted. He says once they start anticipating you, they think they control you.’

‘Your husband does have novel ideas!’ She rose and kissed her daughter’s cheek. ‘I must be off. I’m glad to see you looking so bonny,’ she said.

In the time between Christmas and New Year, Edward traditionally reviewed his clients’ portfolios, and looked into new investment opportunities. It was usually a quiet period, with Parliament in recess and most of his clients out of Town. But the war had changed many things. Weather was too bad at the Front for anything oth

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

The Long, Long Trail

Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved