- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

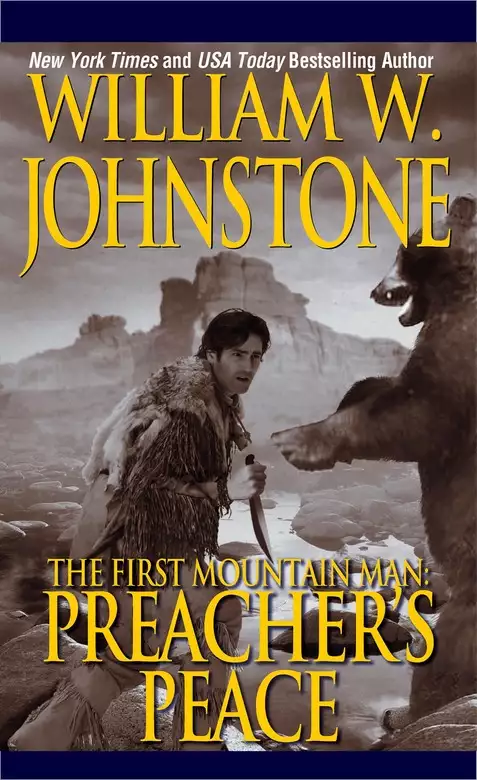

Synopsis

Long before there was a mountain man called Preacher, a young adventurer set off with a team of fur traders from St. Louis for the time of his life. On a wild frontier, he sought a fortune. Instead, he found blood, betrayal, and the beginning of a legend. Armed only with a knife, surrounded by a fierce Blackfoot war party, the young man was forced to kill a warrior chief in an act of audacious courage. But when a grizzly bear attack left him half-dead, he could no longer protect himself. By the time the Blackfeet found him again, he had been abandoned and double-crossed, with only one last trick up his sleeve: the ability to talk himself out of an impossible situation—and into a battle for his life.

So began William Johnstone's masterful saga of the courageous loner who would become known as Preacher. Because when he was alone and desperate, he drew on a preacher's skills—and a mountain man's cunning-to give his enemies hell.

Release date: June 28, 2016

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 288

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Preacher's Peace

William W. Johnstone

The river splashed and babbled over rocks worn smooth by centuries of flowing water. From its depths, trout leaped into the air to snare flying insects that hovered over the sparkling surface. In the sunlit glades nearby, wildflowers bloomed in a profusion of color, scenting the air with their sweet fragrance.

The rider who came onto this scene was an impressive man, with a full mustache, square jaw, straight nose, and steel-gray eyes staring out from under a wide-brimmed hat. He sat his horse easily and was leading two mules, both packed to their maximum carrying capacity with beaver pelts. In a country where a man’s deeds and character counted for more than his family name, this man who would someday be known as Preacher, was still known only by a single name, Art.

Art took a long pull from his canteen, corked it, and hooked it back on the pommel of his saddle, then shifted around to look at the two mules plodding along behind him. For some time now, he had been aware that two Indians were dogging him, riding parallel with him and, for the most part, staying out of sight. They were good, but Art was better. He was on to them as soon as they started shadowing his trail.

Art knew that the Blackfeet were denying white trappers access to the rivers and streams in the upper Yellowstone, but he was well out of their territory now. If these were Blackfeet, what were they doing this far down the Missouri River?

As soon as the stream rounded a bend, Art slipped his Hawken rifle from its saddle sheath, dismounted from his horse, and gave it a slap on the rump to keep it moving along. He wasn’t concerned about the horse and mules getting away—they had been following the stream so rigidly that he was sure they would keep going in that direction, moving slowly and deliberately enough that he would be able to catch up with them again. Using the sharp bend in the stream as concealment, he quickly primed his weapons, cocked the hammers on his rifle and his pistol, and waited.

Art didn’t want to kill them, whoever they were. He knew there were times when one had to kill and when those times came, there was no place for hesitancy. He had killed more times than he wanted to recall, starting with river pirates back on the Ohio River, English soldiers during the Battle of New Orleans, and Indians in various battles in between. And he knew he would kill again, but to the degree that he could, he made a compromise with grim reality. He would kill only when he had no other choice. It was the kind of man he was.

The Indians on his trail approached his position so skillfully that he could barely hear them. Not one word was spoken, and the rocks that were disturbed by the horses’ hooves moved lightly, as if they were dislodged by some wild creature.

Art watched; then as they came around the bend, he stood up suddenly, his Hawken pointed menacingly toward them.

“Ayiee!” one of the Indians exclaimed in a startled shout. His horse reared, and he had to fight to bring it under control. The other Indian raised his bow. The arrow was already fitted. He aimed without hesitation.

“No, don’t!” Art shouted, but his shout had no effect. The Indian released the arrow and it whizzed by Art, coming so close that he could feel the air of its passing. Art pulled the trigger on his rifle; it roared and bucked and poured forth a cloud of smoke. The Indian who had shot at him tumbled from his saddle.

The other Indian, his horse now under control, knew that Art could fire the rifle only once. Realizing that he now had an advantage, he released an arrow toward Art, but missed. Dropping his rifle, Art raised his pistol and fired. The charge in the pistol exploded, sending a shudder through the shooter’s powerful arm. The Indian’s face disintegrated in a bloody red pulp as the ball struck him right between the eyes.

As the powerful echo of the last shot was still reverberating through the canyon, Art went over for a closer examination of the two Indians he had shot. As he suspected, both were dead, but something he didn’t expect was to see that they were Arikara.

Why were the Arikara trailing him? As far as he knew, the Arikara were not causing any problems. Of course it might have nothing at all to do with any problems between the Arikara and the white trappers. These two could well be a couple of renegades just after his pelts. He knew that the load on his pack animals would tempt any thief, red or white.

Art recharged and reloaded both his weapons, then mounting one of the Indian ponies, galloped down the stream until he caught up with his animals. Letting the Indian pony go, he remounted his own horse and continued his journey.

The smoke from hundreds of campfires could be seen from miles away. And if the smoke wasn’t enough, there were also the smells, some pleasant, like the aromas of cooking meat, and others not quite so pleasant, such as the stench of hundreds of mountain men who had neither bathed nor changed their clothes for the entire winter. This was an important gathering place for trappers from the mountains, fur traders from the East, Indians of many tribes, explorers, mapmakers, merchants, whiskey drummers, card-sharks, whores, Indian squaws and their children by various fathers—some of whom might even be here.

For the trappers, this would be their first brush with civilization after a long winter of self-imposed exile in the mountains. It was the only encounter most would have, because they would sell their pelts to a furrier, trade for the few things needed to outfit them for the next year, then spend the rest of their money on whatever items the enterprising merchants would bring with them. Once their money was gone, they would disappear back into the mountains for another long year of solitude.

Though much younger than most of the other trappers, Art had grown to manhood in the mountains and knew the mountains and streams as well as the oldest and most experienced trapper present. He rode into the camp, sloping down a ridgeline leading his two mules.

“Art!” someone called. “Art, how are you, boy?”

The man who hailed Art was Clyde Bames, a longtime friend. Art waved at him, then, using his knees and a tug on the reins, headed his animals over toward him. Dismounting, he tied his horse to a sapling before looking around the sprawling, crowded encampment. The camp was alive with activity, like a giant beehive or anthill.

“Looks like quite a few of the men have made it down already,” Art said.

“Yep, reckon you’re one of the last ones to come in,” Clyde said. He cut a chew off his plug of black tobacco and stuck it in his mouth. “But from the looks of your load there, I’d say you had reason to be late. Looks to me like you had a helluva good year, friend.”

“It was a tolerable year,” Art replied evenly. He was not given to overexaggeration, or much talk at all. He stared across his mule at Clyde as he busied himself unloading the furs.

“Uh-huh,” Clyde said, smiling. “More’n tolerable, I’d say.”

“I was sorry to hear about Pierre Gameau.”

“Yeah,” Clyde said. “I told him he had no damn business goin’ back to New Orleans. He was a mountain man, through and through, not some New Orleans citified dandy-man. But he said that’s where he come from, and that’s where he wanted to die. Pretty definite about it. And that’s what he done, by gar. He died of the swamp fever.”

Art credited Clyde and Pierre Gameau with saving his life. Nearly ten years earlier, Art had been found in the mountains, more dead than alive, by the two men who were then trapping partners. They nursed Art back to health that year, and shared their take with him. They didn’t have cause to help him, could have left him to die all alone out there. Although Art had long ago gone his own way, and sometimes even went for an entire year without seeing either one of them, he had always counted Pierre and Clyde as close friends.

Then, two years ago, Pierre had decided he was too old to spend another bitter winter in the mountains. They threw a memorable going-away party for him at Rendezvous that year.

“You sold your plews yet?” Art asked. “Plew” was another word for pelt.

“Yeah,” Clyde answered. He spat out a dark, evil stream of tobacco juice. “Got me a dollar and a half a pelt for ’em, I’ll tell you.”

Art looked up in surprise. “A dollar and a half apiece? We got two and half last year. Did the market drop on furs?”

“Not as much competition this year,” Clyde replied. “Ashley ain’t sent anyone out.”

William Ashley, who had his office in St. Louis, was the leading furrier, the best known and most respected, and his presence always ensured a fair price.

“He get out of the business?”

“Not from what I’ve heard. He’s still buying furs back in St. Louie. But like the man says, we ain’t in St. Louie.” Clyde gestured around the encampment and wrinkled his nose.

“I reckon not,” Art said. He ground-staked his animals, free of their burden after their long journey, and found a seat on a fallen tree trunk. The weight and tension of hundreds of hard miles melted from his shoulders. Rendezvous was like home to him, maybe the best home he’d had since he was a boy. God, that seemed so long ago, when he had left his ma and paw and the other kids to seek adventure ...

“Say, did you hear about the big battle last summer?” Clyde asked, working another chew in his mouth.

“What battle was that?”

“Twixt the soldiers and the Indians. The soldiers belonged to an outfit called the Missouri Legion.”

Art shook his head and shrugged his wide shoulders. “Didn’t hear anything about it.”

“Well, wasn’t that much of a battle the way I he’ered it told,” Clyde said. “More shoutin’ than shootin’. Couple of white men killed, maybe as many as fifteen or twenty Arikaras. Then the Arikaras run away and that was the end of it.”

“The Arikaras? Not the Blackfeet?”

“Arikaras,” Clyde said.

“Well, then, that might explain it.”

“Explain what?”

Art told Clyde of his encounter with the two Indians on the way down to Rendezvous. He was still bothered by the fact that he’d had to kill them both.

“I thought maybe they were just a couple of renegades,” Art said. “Never thought we’d have any trouble with the Arikara.”

“Yeah, that’s what I thought too. I mean, the Arikaras can be dealt with. It’s the Blackfeet that would as soon scalp you as look at you.”

“What do you reckon got into their craw?” Art asked.

“From what I he’ered, a couple of Ashley’s men traded them some bad whiskey for good plews. Once the Indians sobered up, they realized they had gotten the raw end of the deal. They got even by stealing nearly all of Ashley’s supplies. One thing led to another; next thing you know, there was an army of soldiers and trappers here to teach the Indians a lesson.”

“Doesn’t sound to me like that was any too smart.” In fact, it sounded downright stupid and wrong to Art. “The Blackfeet already keep us out of their country. Sounds like the Arikara are going to be doin’ the same thing. So, with Ashley not here, who’s doin’ the tradin’?”

“Fitzhugh from Cincinnati and Peabody from Philadelphia.”

“Neither one of them’s paying more’n a dollar and a half?” Art asked.

Clyde shook his head. “No. The bastards got together on it, I’m sure of it. Mr. Ashley never would do that. He knows that without us, he’s got no trade. And if we can’t make a decent livin’, then he won’t have us.”

“That’s the long and short of it,” Art agreed. It was the way of trapping and trading, the way he had learned over the years of back-breaking, dangerous life in the mountains.

“You know what they say he’s payin’, back in St. Louie?” Clyde asked.

“What?”

“Five dollars apiece.”

“Five dollars?”

“Yep,” Clyde said. He glanced at the two carrying racks Art had unloaded. “If you could get those plews to him back in St. Louie, why, you’d make yourself a fortune.”

Art examined his pelts for a moment, absorbing the idea of a better, fairer payment. Made sense to him. “Yeah,” he finally said. “Yeah, I would, wouldn’t I?”

“Course, to get that kind of money, you got to take ’em to Ashley Might as well have to take ’em to China, far as I’m concerned.”

“Five dollars?” Art scratched at his jawline, feeling the need for a bath and a bedroll, but adding up the dollars in his mind.

Clyde stared at his young friend. “Art, don’t tell me you’re really thinkin’ ’bout doin’ that.” He brought another foul chew up to the front of his mouth, ready to fire it like a minié ball.

“Five dollars apiece is a lot of money,” Art said emphatically.

“So it is, but what do you need all that money for anyway? What you going to spend it on out here?”

Art smiled. “There’s always things to spend your money on,” he said. “And five dollars is a lot of money.”

“Yeah, you keep sayin’ that. And I keep hearin’ you say it. But Ashley is in St. Louie and you are here. Like as not, if you started out today, you’d be two, maybe three months getting there, and that’s only if everything went like it’s supposed to. You could lose all your pelts along the way. Fact is, you could lose your scalp along the way.”

“Maybe,” Art said. He knew the risks, but was calculating the return in his mind.

“I’ll be damned. You’re going to try it, aren’t you?”

After only the slightest hesitation, Art nodded. “You want to come along?”

Clyde shook his head. “I done sold my catch.”

“Buy ’em back.”

“I done spent all my money.”

“I’ll tell you what. If you’ll come with me, help me get my plews back to St. Louis, I’ll give you a quarter of them.”

“A quarter of them? How many is that?”

“Forty-five,” Art answered. “At five dollars apiece, that would be two hundred and twenty-five dollars.”

“Two hundred twenty-five dollars?” Clyde gasped, almost choking on his own saliva and ’bacca juices. “That’s more’n I made here for a whole winter’s trapping.”

“What do you say? Want to come with me?”

“Hell, yes, I’ll come,” Clyde said, smiling broadly, exposing a jagged row of black and yellow teeth. He ran his hand across the top of his head and spat violently. “I may wind up losin’ my scalp over it, but I reckon it’s a chance worth takin’. Anyhow, it’s been quite a while since I seen me a real town. I might just enjoy that.”

“First thing we’ve got to do is sell off our animals and get us a boat,” Art proposed.

“A boat? Wait a minute, you plannin’ on goin’ all the way to St. Louie by boat?”

“Sure, why not?”

“Why not? ’Cause I don’t feel like paddling all the way to St. Louie, that’s why.”

“You don’t have to worry about that, Clyde. It’s purely downstream all the way, which means the river will take us. All we have to do is put the boat in and keep it in the center of the river. Like slicing a pie.”

“There’s another thing,” Clyde said sheepishly, his eyes squinting. “I can’t swim. Besides which, maybe you don’t have to paddle, but I can’t believe you can just put a boat in the water and expect it to float you there. You gotta know what you’re doin’ and where you’re goin’.”

“I do know what I’m doing,” Art said. “I’ve been on flatboats before. I know the river.”

Clyde stroked his chin as he examined his young friend. “You’re crazy, you know that.”

“You still going with me?”

Clyde laughed. “Yeah,” he said. “I’m still going with you. I reckon I’m crazy too.”

In a place not too far from where the two Indians had attacked Art, several Indian warriors were sitting in a large council circle engaged in the ritual smoking of an ornately carved and feathered ceremonial pipe. The council had been called when the bodies of two of their warriors were brought back to the village. Now the women were weeping, while the men of the village were trying to decide what should be done to answer this outrage. Their honor and the honor of the dead were at stake.

“They were killed by a white man who takes beaver,” one of the council elders said.

The leader of the council, whose name was Buffalo Robe but was called The Peacemaker, held out his hand, and the others looked at him, awaiting his words.

“I know that the blood runs hot in our young men,” he began. “And there are those who would seek revenge.” He put his hand over his heart. “My heart demands revenge as well”—he moved his hand to his head—“but my head tells me this would not be a wise thing.”

“No, no, we must have revenge!” one of the younger warriors declared.

Again, The Peacemaker held out his hand. “I have listened to the words of your heart. But those are words of passion, not words of wisdom. Here is what my head says. Have you forgotten that the white man sent an army against us? Have you forgotten that they had many guns and we had few, and they killed many of our brothers, while we killed but few of them? If we go to war, we will have more weeping among our women, and more of our tepees will be empty.”

“What of Red Hawk and Mean to His Horses?”

“Does the sign not show that Red Hawk and Mean to His Horses attacked the white man? If this is so, they wanted to do battle, and they lost. I say no more war.”

One of the men sitting in the circle was Standing Bear. Standing Bear’s Indian name was Wak Tha Go, and that was the name he used. At six feet six inches, Wak Tha Go towered over every other man in the village, in fact over most men throughout the country. He got his height, unusual for an Indian, from the very tall French trapper who had raped his mother. Now, as the pipe was passed to him, he took a puff into his lungs, then fanned the smoke from the bowl into his face. A medicine man of the Arikara, Wak Tha Go belonged to the Bear Society, and was now wearing a bearskin robe as a symbol of his station. When he stood, wearing his robe, he could frighten those who didn’t know him, for with the robe and his size, he was very much like the bear he emulated. He was a strong, courageous warrior who had proved himself in many battles.

“What does the medicine man-warrior Wak Tha Go say?” the warrior who had been speaking with The Peacemaker asked. He turned to Wak Tha Go. “Do you who stand as tall as the tallest bear counsel peace as well?”

“If you kill the cub of a rabbit, the rabbit’s mother will turn and run. If you kill the cub of a bear, the bear’s mother will turn and fight.” Wak Tha Go looked at The Peacemaker. “The Peacemaker would have us be rabbits.” He fingered the bearskin robe he was wearing, then lifted it with one hand high above his shoulder. “I belong to the Bear Society. I am not a rabbit!” he said resolutely.

“Aiii yi, yi, yi!” the others in the council s. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...