- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

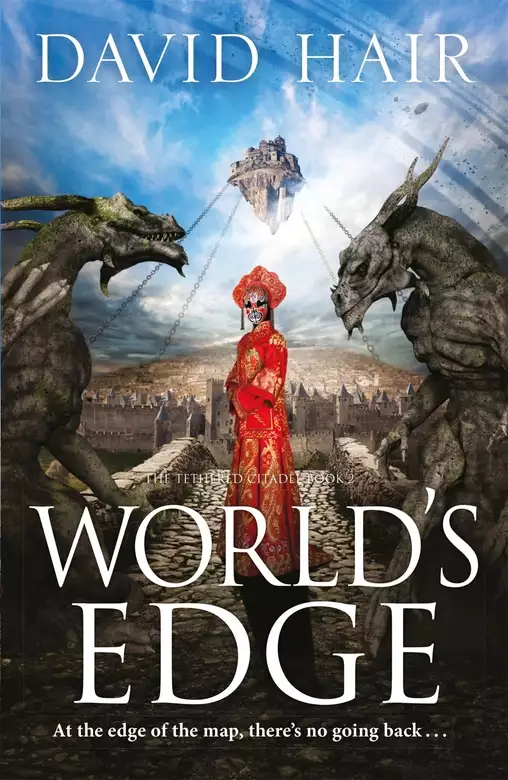

Synopsis

Renegade sorcerer Raythe Vyre went off the edge of the map, seeking riches and redemption . . . but he has found the impossible: a vanished civilisation - and the threat of eternal damnation!

'Apage-turning adventure filled with excitement and intriguing characters . . . an epic fantasywith plenty of sword-fights, gun-play, bare-fisted combat and battles between sorcerers' Amazing Stories

Chasing a dream of wealth and freedom, Raythe Vyre's ragtag caravan of refugees from imperial oppression went off the map, into the frozen wastes of the north. What they found there was beyond all their expectations: Rath Argentium, the legendary city of the long-vanished Aldar, complete with its fabled floating citadel.

Even more unexpectedly, they encountered the Tangato, the remnants of the people who served the Aldar, who are shocked to learn that they're not alone in the world - and hostile to Raythe's interlopers.

What awaits Raythe's people in the haunted castle that floats above them, the lair of the last Aldar king? Everlasting wealth - or eternal damnation?

Release date: October 28, 2021

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

World's Edge

David Hair

There’s just three hundred of us – and there are thousands of them.

For now, all he could do was squint through his spyglass and try to work out what they were facing. He’d never seen people like them, and he was widely travelled. They were all brown-faced, with plump lips and wide nostrils, and dark markings of some sort on their faces. Their bare arms were also decorated with patterned symbols. Their breastplates looked like boiled leather and their weapons were primitive for the most part, spears and bows, although the officers had curved swords, possibly of bronze, judging by the colour, and elaborate helmets of leather and metal. Right now, they were all singing a warlike chant that involved a lot of thigh-slapping and pulling faces. It was undoubtedly unsettling.

At least a quarter of the warriors were women, which was virtually unheard of except during the last, desperate days of the Bolgravian Conquests, when anyone who could hold a weapon had been conscripted, regardless of age or gender. But these women looked every bit as fierce and athletic as the men.

Even stranger, the two dozen advisors clustered about the throne of their female ruler appeared to be women. Their black hair was coiled in elaborate piles, they all wore brightly coloured robes and masks of shining red and black. They reminded him, chillingly, of mosaics he’d seen of Aldar women.

‘I count two thousand, give or take,’ said Jesco Duretto. A light breeze teased the black hair that framed his handsome, olive-skinned face. ‘And there’s nothing but smoke coming from the Bolgravian camp – I reckon these folk have killed them for us.’

‘They might have, but not for us,’ Raythe replied, returning his spyglass to the pale figure kneeling before the queen’s throne. Once again his heart nearly stopped at the sight of that slender fair-haired girl.

Zar.

Feeling his anguish, his familiar Cognatus, perched unseen on his shoulder in parrot form, shrilled angrily.

He’d been told many times that he was heartless and calculating, that he kept his feelings buried too deep, and perhaps that was just. Maybe the Revolt, with all the senseless slaughter and the loss of so many friends and allies, had killed something within him. But seeing his daughter like that made him howl inside.

How she was there, Raythe had no idea, but so much was still unknown right now . . . Was this ruined city actually deserted? Were there other ways in and out apart from the bridge below? And were any Bolgravs still alive out there?

And most of all, where had these tribal people come from, and what would they do?

He was doing his best to conceal his anguish: people needed composure from their leaders, not histrionics. But inside, his stomach was roiling with nausea and fear.

‘Is Cal Foaley back?’ he asked Jesco. The hunter had set off at first light with a group of scouts to reconnoitre this ruined mountainside city.

‘He can’t be far away,’ Jesco replied. Looking up, he shuddered and added, ‘This is the strangest place I have ever seen, bar none.’

Raythe followed his gaze past the ruins of multi-storeyed stone buildings that crowded above their position, many with strange curves and crenulations more akin to art than architecture, to the huge floating rock half a mile above the ground, tethered in place by four giant chains, every link bigger than a man. Atop that, partially visible, was a fortress.

‘Rath Argentium,’ Raythe breathed. ‘The royal seat of the last Aldar King – and Shiro Kamigami, the floating citadel. I never believed either was real.’

‘Nor I,’ Jesco replied. ‘They say that when he realised that his reign was doomed, Tashvariel the Usurper locked himself and his courtiers in the banquet hall up there, and for three days and nights they ate and drank and screwed until they were utterly sated – then they took their own lives, rather than yield. They say he murdered his lover Shameesta before he killed himself, and that he haunts the castle still, raging against the gods . . .’

‘Enough with the ghost stories.’ Raythe grinned. ‘It’s quite scary enough already.’

Across the bridge, the fierce song and dance of the warriors ended and Raythe tensed, anticipating attack. But instead, another song began, this one mournful rather than a rousing call to arms.

‘It’s got a weird beauty to it, don’t you think?’ Jesco remarked. ‘I wonder who they are?’

‘They must be survivors of the fall of the Aldar,’ Raythe answered.

‘Holy Gerda! But if that’s so, why aren’t they in here?’

‘No idea.’ Raythe turned as boots thumped on the stone steps behind them and Cal Foaley, a lupine hunter with weather-beaten skin and tangled grey hair, appeared with his flintlock slung over one shoulder.

‘Boss. All the scouts are in.’

‘And?’ Raythe found himself instinctively matching his gruff tone.

‘Everyone’s accounted for, except your daughter and Banno Rhamp. We lost six, with thirteen wounded, in the hill-fort engagement with the Bolgies. Everything we could carry is inside, including all the large gear – we hauled it over in handcarts. We’ve got enough powder and balls for half a hundred volleys, and about as many arrows. Food for a week. No fuel for fires, but there’s trees we can cut down, and we’ve found steps to the river below. Varahana’s organising water containers and my cousin Skeg swears he’s seen fish.’

‘Do we have any way of catching them?’

‘Skeg was a fisherman – he’s working on it.’

‘Good. What about the city? Is it empty? Secure? Are there other ways in?’

‘Gan Corbyn’s scouted the periphery. He says the rivers completely encircle the city – it’s actually an island – and this is the only bridge. There was another one on the north side, but it’s collapsed, ages ago, looks like. The cliffs are sheer, but there’s half a dozen sets of steps leading down to the river, and some old stone docks. No boats, though,’ Foaley added, when Raythe looked alarmed. ‘They don’t look like they’ve been used for many decades.’

‘Let’s station guards at each stair, regardless,’ Raythe ordered. ‘The only advantage we have is that we’re inside and they’re outside. Let’s not lose that.’

‘Ahead of you, boss. I’ve got Rhamp’s mercs at each vulnerable point.’ Foaley’s tones told Raythe exactly what he thought of Sir Elgus Rhamp and his men.

‘About them—’ Jesco began, but Raythe shook his head.

‘Later,’ he said firmly.

Jesco and Foaley both scowled, then the hunter went on, ‘Most of the houses are wrecked and overgrown, but there are still many that are intact, enough to shelter us. Kemara’s set up her infirmary over there’ – he gestured behind the gatehouse – ‘and Gravis Tavernier has found what he reckons is an old inn – it’s still got its ovens and furnaces. And Matty Varte has found an old garden with plenty of fruit and vegetables. He didn’t recognise them all, but if they’re safe to eat – and why else would someone have been growing them? – there’s enough food for the short term.’

‘That’s encouraging.’ Raythe replied. ‘Get Mater Varahana on it. She’s a scholar – she may be able to identify them. How’re the wounded doing?’

Foaley looked down. ‘Vidar’s the worst, I fear. The bearskin’s at death’s doorway. And Fossy Vardoe took a bayonet in the chest. Kemara reckons he’ll make it, though. The rest of the injuries are mostly minor.’

‘I’ll visit them when I can,’ Raythe said as the latest song ended. ‘Hold on, what’s this?’

A small cluster of warriors were forming up on the bridge behind a figure wearing a long cloak made of what looked to be red, green and brown phorus feathers. Raythe leaned over the battlements and shouted down to the men aiming flintlocks and bows along the arched bridge, ‘Don’t shoot at the group moving onto the bridge unless I order it.’

From his higher vantage, he watched the tribesmen advance. When he trained his spyglass on their leader he was surprised to see a young woman with lustrous black hair and strong, attractive features. Her face bore similar markings to the men and he wondered if it was paint, or even tattoos?

‘It may be a parley,’ he reported, repeating, ‘Don’t shoot.’

‘Aye, we hear you,’ the gruff voice of Sir Elgus Rhamp called from below.

They watched in silence as the knot of warriors crested the apex of the bridge, then stalked towards them. The strange way they were holding their spears, close to the bronze heads, made Raythe wonder if they were actually spears at all. The men were clearly apprehensive, but the young woman looked completely calm.

‘All right, listen,’ he called out, ‘Jesco’s going to fire one shot in the air, as a warning. It is not a signal to open fire! Understood?’

‘Understood,’ the voices chorused.

Raythe nodded to Jesco, who pointed his flintlock skywards and pulled the trigger. The hammer dropped and sparked and the gun shot flame and an iron ball into the sky. The sound reverberated in the ravine, scattering the circling birds.

The men on the bridge flinched, looking round in alarm, which confirmed Raythe’s suspicion that they’d never seen a gun before. But the woman spoke sharply and kept walking. A low murmur rose from his men below as she emerged from the press: she certainly was an impressive sight. Her feather cloak blew out behind her, revealing just a beaded kilt and bodice which left her waist and well-muscled thighs and calves bare.

‘Do I shoot again?’ Jesco asked, reloading swiftly.

‘Wait,’ Raythe said. When she was a hundred yards from the gatehouse, he called out, ‘That’s far enough—’ He didn’t expect her to understand, but hoped she’d infer the meaning.

She halted, and called, ‘Are you . . . Rat Weer?’

He blinked in surprise. ‘I am Raythe Vyre,’ he shouted back. ‘Do you speak Magnian?’

He saw the woman mutter to herself, then she called back, the words slow and awkwardly pronounced, ‘Your Magneeyan is like our “Gengo”. And my familiar can help translate.’

Below him, Raythe’s gunmen whispered, ‘Familiar? She’s a sorcerer!’

Or a witch, Raythe thought grimly, for the Aldar had used mizra, not the praxis. The masks the queen and her women wore suggested that if these people weren’t Aldar themselves, they clearly had memories of the long-vanished race.

This isn’t a conversation I want to have in front of my people, he decided.

‘May I approach you?’ he called.

She considered, then called, ‘Ae – that is “Yes”.’

He gave Jesco a wink. ‘Cover me.’

‘Sure . . . Rat Weer.’

Raythe snorted and descended, once again warning his people not to shoot anyone without his express command. Then he clambered over the barricade and walked out onto the span, feeling very exposed.

The woman came to meet him. Up close she was surprisingly young, a portrait of vitality, with an expressive face.

I wonder what kind of legend I’ve stepped out of in her people’s mythology?

‘What’s your name?’ he asked.

She cocked her head, listening to her familiar, a lizard sitting on her shoulder, then said, ‘My name is Rima.’

‘I’m Raythe Vyre,’ he said, emphasising the pronunciation. ‘How can you know Magnian?’

‘This is not “Magnian” we speak, but Gengo,’ Rima replied slowly. ‘It was the use-tongue of the Aldar Kingdoms. It is not our first tongue, but we have preserved knowledge of it, and mahotsu-kai like me learn it.’

Raythe felt his wonder deepen. ‘Then “Gengo” has become Magnian . . . Incredible.’

‘Ae. When I heard your daughter speak, at first I did not realise it was the same tongue, for her pronunciation is strange. But I have communed with my familiar since then, and attuned to your accents. Hence, we are speaking now.’

Raythe frowned at that: Cognatus could obey simple, well-drilled instructions, but not of the subtlety required to learn a language.

This Rima is young, but she’s got real skill, he realised.

He had a million questions, but one burning need, and that was to secure his people’s position. To that end, he put aside the mysteries and said, ‘I seek a truce.’

She shook her head. ‘The city is tapu. Leave it, and we can discuss truces.’

‘Tapu?’ It wasn’t a Magnian word.

She conferred with her familiar, then clarified, ‘This word tapu comes from our main tongue – “Reo”. Tapu means sacred and forbidden.’

Two languages . . . He was getting the impression that these were a people with two identities, one, the warrior culture; the other that of the silk and masks. Servants and masters? And they clearly recalled the Aldar.

He was careful to conceal his growing unease and awe. ‘We’re not leaving,’ he said firmly. ‘I wish to speak with your leader.’

‘She who leads us is Shiazar, Great Queen of Earthly Paradise, Guardian of Death’s Threshold, Empress of the Tangato and Serene Divinity of Light. You are not worthy to meet with her.’

Raythe doubted that even the Emperor of Bolgravia claimed so many titles. ‘I am Lord Raythe Vyre, Earl of Anshelm. I have met with rulers of larger nations than your own. I will speak with your queen.’

‘We have your daughter,’ Rima pointed out. ‘You do not set the terms.’

‘The life of one does not override the needs of the many. Do not threaten her.’

Rima mellowed her tone. ‘Your daughter is not threatened. My tribe have adopted her.’

Raythe was momentarily stunned. ‘She’s on a leash at the feet of your Empress.’

‘No unknown may bear weapons before the throne, and magic is a weapon. The cord resists sorcery. It is necessary for any unproven sorcerer who goes before our Queen.’

Raythe was impressed: such artefacts took skill to make. They might have primitive weapons, but that doesn’t mean their sorcery will be backward, he reminded himself. ‘Release her, and we can talk.’

Rima shook her head. ‘A sorcerer is sacred and must serve Her Serene Majesty. She will learn our ways and live as one of us.’

‘No, she will not.’

‘The alternate was to put her to death. Would you prefer we had done so?’

‘I warn you—’

‘Do not “warn”,’ Rima said sharply. ‘You have come as thieves to a sacred place. Go home, never return, and give thanks that your daughter’s service has obtained this for you. You have three days.’

With that, Rima turned on her heel and walked gracefully away as if three dozen flintlocks weren’t trained on her back – although Raythe suspected she didn’t know what a flintlock was. He replayed her words in his mind, thinking about what they revealed about her and her people.

‘Wait,’ he called.

She turned, head held high. ‘Yes?’

‘Was my daughter alone?’

The girl pulled a thoughtful face, then said, ‘Her husband is with her. He is also safe.’

Husband? Well, Zar wouldn’t claim to be married without reasons.

Keeping his face impassive, he asked instead, ‘What is required for me to meet Queen Shiazar?’

Rima considered. ‘Her desire to meet you. Perhaps it may occur.’ She turned once again and strutted away.

‘She’s quite a woman,’ Foaley breathed when Raythe got back to the barricade.

‘Rather wonderful,’ Jesco agreed admiringly.

Raythe stared after her as the men on the walls and below began to relax and chatter. ‘Right,’ he said eventually, ‘we need a leaders’ meeting. Cal, take charge here.’

After Foaley had saluted offhandedly and sauntered away, Jesco dropped his voice and said, ‘Raythe, Elgus Rhamp tried to change sides last night, then covered it up when the Bolgravian attack failed. You’ve got to deal with him, once and for all.’

Raythe shook his head. ‘It’ll have to keep for now. We need every man, and if I turn on Elgus, his men will defend him. But I will act, I promise, when the time is right.’

*

Sir Elgus Rhamp stared along the bridge, quietly simmering. He should never have joined this cursed expedition. I should’ve knifed Vyre and claimed the bounty instead.

The dream that had lured him was now right here: Rath Argentium, and above it a rock so riddled with istariol that it floated, a miraculous place indeed.

But this expedition has cost me two of my sons – maybe three, ’cause no one knows where Banno is – and it’ll probably be the death of me.

His two lieutenants, grey-bearded, calculating Crowfoot and swarthy, belligerent Bloody Thom, joined him. Raythe Vyre wanted a meeting, but he needed their thoughts before that. He found a secluded courtyard and waved his seconds in.

‘How’re the lads?’ he asked the pair, once he’d assured himself they were alone.

‘Their heads are spinning,’ Crowfoot replied. ‘Floating castles, lost tribes, Aldar ruins? It’s like we’ve fallen off the edge of the world.’

‘But most of all, the lads don’ know what side we’re on,’ Bloody Thom added. ‘Last night, we were about to help the damned Bolgies, then we kragged ’em instead. Deo knows we hate those bastards, but Vyre needs to go down – so damned right our heads are spinning.’

That was fair. Changing sides twice in one night was a first for them, but it’d been a crazy situation, and as it turned out, he’d made the right choice.

‘You were there: Jesco Duretto and his lot had the Bolgies cold – and then those savages hit their rear. If I hadn’t two-stepped us out, we’d have gone down with them.’

‘You didn’t know that was coming, Elgus,’ Crowfoot replied. ‘You made that call purely on gut.’

‘And my gut got it right,’ Elgus boasted, slapping his ample girth. ‘Sometimes it ain’t the logic but the feel, and that attack din’t feel right. Vyre’s people had the high ground and the Bolgies wanted us to charge into their guns. I pivoted, and I was right to.’

Bloody Thom got it, he could see. He understood that while large battles were decided by numbers and firepower, skirmishes like last night got settled by luck and cosmic energy. And three times now, Vyre had led his caravan safely out of the empire’s jaws.

The gods are with him, my Pa would’ve said.

Focusing on Crowfoot, who was all about numbers and tactics, Elgus said, ‘Vyre has the upper hand, and Duretto suspects us. We play along and wait our moment.’

‘Elgus, even if that Bolgrav force was wiped out, they must’ve told their superiors where they were going,’ Crowfoot replied. ‘They’ll be back and we need to be gone – with a shitload of istariol – before they do.’

‘Maybe, but it’s just as likely that Bolgrav force was operating on their own. Who’s to know if they left adequate directions? Verdessa’s a new settlement and things are loose in such places. And in case you’ve not noticed, there’s an army of savages out there,’ he replied. ‘Until we know more, we play along. Got it?’

Both of his lieutenants grumbled into their beards, but at last they grunted assent.

‘Look, I’m chewed up over it too,’ he told them. ‘But I’ll see us right. I always have.’

With that, he headed for Vyre’s meeting, readying the lies he’d need to hide what he’d done last night. But his thoughts constantly returned to his one remaining son.

Banno was last seen with Zarelda Vyre and she’s a prisoner – so where’s my boy?

*

‘Well?’ Crowfoot growled.

Bloody Thom hunched over, seething. ‘Elgus is deluding himself. I reckon we’ve got two, maybe three months before the empire returns. By then, we’ve gotta be gone.’

Crowfoot considered. ‘Aye, a month for anyone who escaped to reach Rodonoi, a month to get their shit together and muster, then a month to get back here. Three months.’

Thom leaned in and murmured, ‘You reckon he’s still got the balls for this?’

‘I don’t know,’ Crowfoot admitted, and that was painful to say. They’d all been through so much together, all the chaos of the imperial conquests and the rebellions. ‘He’s got to assert himself with Vyre or that slimy Otravian will sell us all out, you watch.’ He enumerated their enemies, finger by finger. ‘Jesco Duretto. Vidar Vidarsson. Kemara Solus. Mater Varahana. Cal Foaley. Vyre himself. Six backs, six knives.’

‘Aye. And maybe seven, if Elgus don’t see us right,’ Thom growled.

Hour by hour, the day passed. Zarelda Vyre’s knees first ached, then degenerated into throbbing agony, while the Tangato queen sat above her, masked and draped in silk, a regal doll who never moved. Her courtiers fluttered about the throne, elaborately accoutred and alien in their masks. At one point, Rima went across the bridge. When she returned, she held a whispered conference with Hetaru, the ancient sorcerer, after which he spoke to a masked woman who whispered in the Empress’ ear.

And the massed Tangato warriors waited patiently.

Please, Father, she thought, I beg you, get me out of here.

Yet again, she tested her bonds, but the leash round her neck was strong, and it had a binding effect on her praxis. Adefar was inside her, translating if she asked, but when she tried to burn the leash away, the spell fizzed out like a candle thrown into water.

All the while, the Tangato men sang in their sonorous voices, alternately martial and aggressive, then sorrowful. But then it began to rain, the first cold drops on her skin making her shiver, then the skies wept, as grey clouds swirled in, almost concealing the impossible floating fortress above the city.

In moments she was soaked.

Men came running in and held giant woven fans over the Queen’s head while they lifted her throne – with her still sitting on it – and manhandled it into her palanquin. Then Rima darted in, her feather cloak streaming with rain, plucked the leash from its ground peg and wrapped it round her arm before hauling Zar to her feet, having to support her when her knees screamed and refused to bear her.

She commandeered a warrior’s cloak and draped it over Zar’s shoulders, saying in accented Magnian, ‘Come, we return to the village.’

Their initial conversations had been held with Rima’s familiar intermediating – a sophisticated use of a familiar; Zar hadn’t thought them to be so capable. But that morning, Rima had arrived speaking Magnian, saying she’d now realised that Zar’s language was the same as Gengo, an archaic language her people used in ceremony. It was a remarkable thing, and a real relief to be able to communicate at all.

Zar looked around to see the massive Tangato force, two thousand men at least, were on the move, trotting east towards the low hills that divided this place from their village. Even though she was being led away from her own people, right now all she wanted was to be out of this freezing rain and reunited with Banno.

She made it half a mile before her legs cramped up and she fell, howling in pain, and this time Rima had some men hoist her into a roofed palanquin that appeared from Deo knew where.

The rocking of the conveyance had her asleep in seconds.

*

When Zar woke after what felt like seconds, the rain still fell down, reducing the ground to thick mud, and the palanquin was being lowered. Four strong young warriors were chuckling over her, and when one offered her a hand, she wasn’t too proud to accept.

Rima appeared, her black hair soaked flat and her cloak turned inside out to protect the feathers, revealing the lining to be some kind of hide. They were amongst a sea of pole-houses made of wood with timber-slatted roofs and huge, dramatic red-daubed gables and ridges, many carved with dragons or demonic faces. Wooden walkways ran between gardens and bigger buildings – communal halls or temples, maybe – dotted amidst the hundreds of smaller dwellings, and smoke rose from every chimney. Brown-skinned Tangato were everywhere, the bedraggled warriors being greeted by women in colourful gowns. They all had facial tattoos and mostly dark brown eyes, peering curiously at Zar as she was lowered.

All she’d seen last night was the odd fire and silhouettes; now she realised that had she seen the village in daylight, she’d have had a completely different impression of these people. This place is properly old, she realised, the way things at home in Otravia are old.

Rima helped her up the steps into a tidy little house and even in her exhausted state, Zar could see it was beautifully constructed, with whitewashed, well-sealed outer walls and a carved doorframe stained red. Inside, the wooden walls were polished. There were carved pillars, like the pou-mahi poles they’d seen in the countryside, intricately detailed. Everything screamed of craftsmanship and house-pride.

A young girl had pots of something simmering on a fire burning in a central pit. There were mats on the ground and blankets of hide and feathers, and against the walls were stacked crockery, cooking implements, clothing, footwear and more blankets. While Rima wrung out her hair in the doorway, Zar collapsed onto a floor-mat beside the fire.

‘Where’s Banno?’ she asked.

‘Next house,’ Rima replied calmly. She dismissed the young girl and once they were alone, she removed Zar’s leash, then called Adefar and somehow sucked the little familiar into a jade pendant around her neck.

‘Hey, give him back!’ Zar gasped – she’d never seen such a thing. To be stripped of her familiar, and therefore her access to magic, was terrifying.

‘To remove temptation,’ the young Tangato sorceress replied. ‘Prove your loyalty and it will be returned.’

Zar jabbed a finger to her own newly tattooed chin. ‘You brand me like a slave, then speak of loyalty?’ But when Rima didn’t rise to her anger, she sagged again, exhausted.

At least we can talk, she thought numbly. It was still stunning to think that after five hundred years of separation, she and Rima shared the same language, although with hugely different accents and some vocabulary mismatches.

‘Where’s Banno?’ she asked again.

‘Your husband is in the next house, recovering.’

Zar had lied about being married to Banno, but it was possibly the only reason he’d not been killed already. If she didn’t warn him, the deception would unravel. ‘May I see him?’

‘Of course,’ Rima replied, as she shrugged off her cloak. ‘First, you need to understand your situation. You are accepted here as a mahotsu-kai – your word is “sorcerer” – and you are free to be with your husband. Should you leave us without permission, or turn against us, then your husband must die.’

‘Then we’re both prisoners!’

‘No, you are both Tangato now: you, because you are a sacred mahotsu-kai; he, because he is your husband. No other foreigner would be treated so generously.’

From what Zar had seen, what ‘mahotsu-kai’ really meant was ‘mizra-witch’, for that was what Rima and her master Hetaru were surely using. Zar had heard them speak Aldar words – mizra words – to their familiars, and that was terrifying.

But they didn’t want to kill her right now, and her father was still alive, so knowing that, her duty was clear. I have to survive and learn about these people. Father will come for me.

That thought gave her heart, and when Rima ladled stew into a wooden carved bowl and handed it to her, Zar found she was ravenous – she’d not eaten since midday yesterday. There was no cutlery, but she followed Rima’s example, rolling the meat and vegetables in the rice, then eating with her fingers. The stew was gently spiced, nourishing and tasty – and gone in moments. She was beginning to feel just a little more human.

‘You have suffered today, but you stayed strong,’ Rima praised. ‘Hetaru was proud of your demeanour.’

Zar didn’t care in the least about their approval. She was exhausted, but she had some urgent questions she needed to ask, starting with, ‘Who are you people?’

‘We are the Tangato,’ Rima answered proudly, ‘and these lands are our fenua – our home. But who are you?’

Dear Gerda, Zar thought, realising how much they had to catch up on. She’d never been the most academic of students, but she tried to summarise five hundred years of history. ‘When the Mizra Wars triggered the Ice Age, people fled to the equator, where there is no ice—’

‘What is “equator”?’

‘It’s the band around the middle of our world that’s free of ice,’ Zar replied. ‘How can you not know? You’re only three weeks’ walk from Verdessa and the sea!’

‘Truly? Long ago, we sent explorers, but few returned and those who did found only ice. We believe – believed – that we were the last people left alive.’

Zar swallowed. ‘There’s millions of us.’

Rima’s whole demeanour changed to something like dread. ‘Millions?’

Is this something I could exploit? Zar wondered. But the warmth, the food in her belly and her exhaustion were making her yawn, despite her amazement. ‘Please can I see Banno?’ she begged. Before I collapse.

Rima immediately understood. ‘Of course. We can talk more tomorrow.’

Zar sagged in relief: she felt like she

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...