- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

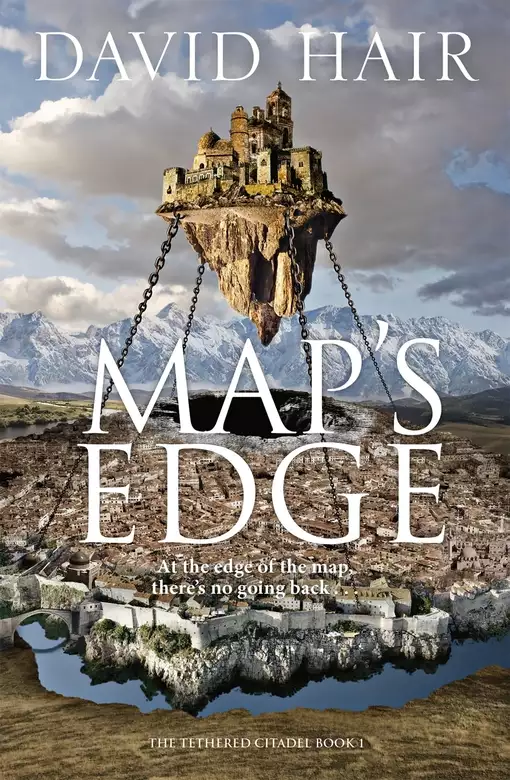

Follow a renegade sorcerer off the edge of the map, in a thrilling adventure perfect for fans of Scott Lynch, Brandon Sanderson and Sebastien de Castell . . . 'A page-turning adventure filled with excitement and intriguing characters. For those loving an epic fantasy with plenty of sword-fights, gun-play, bare-fisted combat and battles between sorcerers, this book's for you' Amazing Stories Soldier, sorcerer and exiled nobleman Raythe Vyre has run out of places to hide. When the all-conquering Bolgravian Empire invaded, Raythe grabbed his daughter Zar and after taking part in a disastrous rebellion, they washed up on the edge of the continent. Now he's found a chance of redemption for himself and the precociously talented Zar: a map showing a hitherto unknown place that's rich in istariol, the rare mineral that fuels sorcery. Mining it will need people, but luckily there are plenty of outcasts, ne'er-do-wells and loners desperate enough to brave haunted roads through the ruins of an ancient, long-dead civilisation, to seek wealth and freedom. But the Bolgravian Empire is not about to let anyone defy it - and even out here, at the edge of the map, implacable imperial agent Toran Zorne has caught Raythe's scent. 'There's a lot of cool stuff, ancient civilisations, magic, a heist, personal loss, love, and humour. I enjoyed this so much' Alalhambra Book Reviews

Release date: October 15, 2020

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Map''s Edge

David Hair

Then he woke fully, staring around the dimly lit cabin, blinking away those memories, but the fist kept pounding, and now a rough voice called, ‘Oi, physicker: wake up!’

‘Dad?’ Zar called in a shaky voice from the loft.

‘Shhh,’ Dash hissed, peering at the door. He could see the flicker of torchlight through the cracks in the crude log cabin. It wasn’t yet dawn and the wind was making the pines creak and hiss. Breakers boomed distantly, a mile away.

No one comes out here at this hour. Then a hundred potential reasons suggested themselves, all sinister. ‘Stay hidden,’ he hissed at Zar, as he hurriedly dressed. ‘Keep your curtain pulled.’

‘Oi, wake up!’ that voice shouted again.

‘Coming.’ Dash staggered blearily to the door, bracing himself against the frame as he composed himself. His mouth felt sour, his head ached dimly.

Too much blasted rye last night.

Never open the door after dark in Teshveld, he’d been told within hours of arriving in this Gerda-forsaken seaside village. He checked the door bar was in place and called, ‘Who is it?’

‘It’s Gravis, from the inn. I got lordships out ’ere, needin’ a physicker.’

‘What?’ There’re no ‘lords’ in Teshveld. But it was definitely Gravis’ voice.

Then a cold male voice called in a Bolgrav accent, ‘Open door or we break, yuz?’ The voice was deep and atonal, every syllable laden with ponderous authority.

Shit, what’s a Bolgrav doing here?

Zar poked a pale face through the loft curtain, Dash signed, Pull your damn curtain shut, then unbarred the door before it was broken.

A mailed fist flew through the opening and stopped an inch from his nose. Dash peered around it at a big, rugged man with greying hair and a beard like steel wire: a Norgan ranger, at a guess, in his forties or fifties. His pale blue eyes widened, but he didn’t drop his clenched fist as he studied his host.

The Norgan didn’t look impressed, which was understandable. Dash knew he didn’t cut a heroic figure – just a slim man in his thirties, with intense eyes, greying black hair and a rudder-nose, passably handsome in a good light, but stubble-chinned and dishevelled right now.

‘That’s ’im, our physicker,’ Gravis wheedled. The guttering torch he held cast everyone in a ruddy light. ‘Dash Cowley, ’is name. Came ’ere four months ago. First proper healer we’ve ’ad in years.’

‘Cowley,’ the Bolgrav voice drawled; it belonged to a man in a noble’s finery, standing behind the Norgan: clean-shaven and pristine, with a blond mane and haughty caste to his face. His pale cloak was collared with blue fox fur, elegantly out of place in this coastal backwater, but his clothing had a lived-in look, as if he’d been travelling a long time. ‘You treat sick friend, yuz,’ the Bolgrav told him.

Frankly, I’d rather cut your Bolgravian throat than tend your bloody friend, Dash thought, but the Bolgrav had three more soldiers – his own countrymen, judging by the conical helms and long flintlocks hanging over their shoulders – as well as the Norgan. One was a sergeant; the other two bore a stretcher containing a swaddled shape. Steamy breath hung over them; overhead, the planetary rings, silver bands of light that carved the sky in two, glowed like the blades of a sky-god.

Kragga, the Bolgrav probably is a lord . . . but what’s he doing out here?

‘He’s right where I said, Lordship,’ Gravis bleated, cap in hand. ‘It’s a cold night, an’ a long walk.’

‘Pay him, Sergeant,’ the Bolgravian snapped. ‘You, Physicker Cowley: where from is you?’

‘I’m Otravian,’ Dash said truthfully; his nose was proclaiming that for him anyway. ‘My rates are—’

‘We pay what you earn; what you deserve, ney?’ the Bolgrav rasped, turning the ‘w’s to ‘v’s. He shoved Dash aside and stalked into the cabin, eyes flashing to the curtained loft. ‘What is up there?’ When Dash hesitated, he added, ‘I send men anyway, so you tell now.’

‘My, ah, child,’ Dash admitted. ‘Zar, show your face.’

She poked her head through the curtain, all freckled cheeks and big eyes.

‘Ah, young girl, yuz?’ the Bolgrav purred. ‘You, girl, come down.’

‘Get dressed first,’ Dash called, gritting his teeth. If this bastard mistreats her . . .

But the best chance of getting rid of the Bolgravs would be to comply as quickly as possible, so he lit the oil-lamp, hurriedly cleared his table, then stood back as the soldiers hoisted the stretcher onto the table. It held a plump redheaded man who was flushed red, sweating badly and stinking of piss and faeces. His right side was encased in bloody, badly wrapped bandages.

‘What’s happened to him?’ Dash asked, wondering if it was even safe to touch the man. ‘Uh, my lord . . .?’

‘Lord Vorei Gospodoi, am I. You speak Bolgravian? Be easier.’

Dash did have some Bolgravian, but he wasn’t about to admit it here. ‘Just Magnian, milord.’

The Bolgrav grunted in displeasure. His eyes fixed on Zar as the thin girl clad in a boy’s shirt and trousers clambered down the ladder. He blocked her from reaching Dash, ignoring her flinch as he stroked her cheek. ‘Mmm. Soft, like all Otravians, ney? What is name, girl?’

‘She’s called Zar,’ Dash answered for her. ‘She’s my nurse. I need her help to treat this man.’

Gospodoi smiled coldly, but stepped aside, allowing Zar to dart past.

‘Cowley, you will heal this man, or bad thing happens for you and daughter.’

Kragging Bolgravs, Dash thought. We crossed a continent to escape arseholes like you.

‘I’ll do my best,’ he answered, ‘but I need to know what ails him.’

‘This man has unknown illness, from northwest.’

‘The northwest? But there’s nothing out there—’

Gospodoi fixed him with a frosty eye. ‘I tell you this, you not repeat, ney? He fell ill in place across Narrows, name is Verdessa.’

The new-found land? Rumour had it there was nothing there but a thin band of rocky shore below the ice-cliffs, but of course, the empire was just getting started over there. Despite himself, Dash was interested. ‘Verdessa – yes, I’ve heard of it.’

‘Is new place.’ Gospodoi smirked. ‘All new places is found by Bolgravians. We are greatest nation, conquer all of Shamaya, yuz. Explore, expand, exploit. You will find, Otravian, no matter where you go – and whoever woman you meet – that Bolgravian man has been there first.’ He chuckled, then jabbed a finger at the sick man. ‘This man is cartomancer. You know cartomancer?’

Holy Gerda! ‘Yes, I know what a cartomancer is,’ Dash admitted.

‘Excellent. You educated man, is good. So you must save him, yuz?’

‘I’ll do my best.’

‘You will,’ Gospodoi agreed, ‘or I break your hands . . . and maybe hurt pretty daughter?’

Bolgravs: every other sentence a threat. ‘How long has he been ill?’

‘Two week.’

‘That long? Was there no one in Verdessa or Sommaport you could take him to?’

Gospodoi went to answer, but the complexities of translating from his tongue to Magnian flummoxed him and he scowled at the Norgan. ‘You tell, Vidarsson.’

The Norgan spoke up. ‘I’m Vidar Vidarsson. The cartomancer’s a Ferrean named Lyam Perhan. He fell ill near the edge of the Iceheart, in northern Verdessa. We’d completed most of our work anyway, so we journeyed south to the coast and Perhan seemed to be rallying, so we sailed south for Sommaport. But he declined after we left Sommaport. Teshveld is the first village we found on this road.’

‘Yuz, is as Vidarsson say,’ Gospodoi put in. ‘You medicate Perhan, make him healthful.’ He stroked Zar’s hair, then turned on his heels curtly. ‘Vidarsson, you will stay and watch, with my men. I stay in tavern.’

Of course you will, Dash thought sourly, and you’ll probably drink their best grog and not pay. But that was Gravis Tavernier’s problem. His was to somehow save this cartomancer.

As Lord Gospodoi stalked off without a backwards glance, Dash turned to Zar and issued a string of instructions: for boiled water, for sedatives and for the herbal poultices he’d been preparing for the next slaan-fly outbreak. Outside, the Bolgrav soldiers were making themselves at home, pissing against his back wall and stealing his firewood while guffawing in their guttural tongue.

Once the Norgan ranger had taken in the lie of the land, including checking the two mules in the lean-to out the back, he sat at Dash’s table, sniffing the wine jar. ‘Rannock claret?’ He poured himself a mug. ‘You bring it with you from home?’

Questions weren’t welcome, and nor was someone stealing his wine, but the Norgan was a hulking man with an air of violence, so Dash limited his response to sarcasm. ‘I traded for that, Vidarsson.’

‘Call me Vidar,’ the ranger growled, pouring himself a mug of the claret. He had craggy features and a pulsing vein in his right temple. ‘So what’s an Otravian healer doing in this Gerda-forsaken hole?’

‘I ask myself that every day. But we take oaths to heal where sickness is found.’

‘Most healers I’ve met are motivated more by coin than oaths,’ Vidar grunted. ‘And most men who live in shitholes like this do so because they don’t want to be found.’

‘I bet most of those don’t really want to talk about it, either,’ Dash observed. ‘Now, if you don’t mind, I’ve got to look after your Bolgravian cartomancer friend if I’m to save my hands.’

‘No friend of mine,’ Vidar said, swigging his wine. He wiped his mouth. ‘Good drop, this.’

‘You’re welcome,’ Dash grunted. ‘So why’s a Norgan nursemaiding a bunch of Bolgravs?’

‘Because I happen to like Imperial argents in my purse,’ Vidar growled. ‘And they’re the only game in town.’

‘You guided them in Verdessa? What’s out there?’

‘That’s none of your concern, healer. Get on with it and I’ll keep your wine company.’

Dash quietly fumed, but he and Zar began their task, removing the cartomancer’s clothes, cutting away the soiled bandages and revealing the wound: a scab-crusted puncture that was seeping foul-smelling fluid. That’s no ‘illness’, Dash thought, having to stop himself retching at the stench.

‘Never seen a healer get all spitty over a bad smell before,’ Vidar observed sagely.

‘I have a sensitive nose,’ Dash replied. ‘Aromatic herbs, Zar.’

‘Maybe you’re just a kragging useless healer,’ Vidar sniffed. ‘Or a fraud?’

That was too close to the truth, but Dash kept his composure. ‘What happened to him?’

‘Fell through some ice onto a buried branch,’ Vidar sniffed. ‘Useless outdoorsman, he was. Had to baby him through the journey. Reckon there’s rotting debris in the wound.’

Dash poked around and nodded in agreement. ‘The wound’s become infected. His blood’s turning septic. It’s only the clotting around the wound that’s preventing the poisoned tissue from circulating and killing him. What do you suggest, Zar?’

Zar’s fifteen-year-old face was screwed up in horror at the foul-looking wound, but she managed a coherent response. ‘We wash, cleanse, cauterise, then apply a poultice.’

‘Good,’ Dash said with approval, ‘but consider his respiration and overall wellbeing: can he survive cauterisation, do you think? And what about sedation?’

Zar considered and they batted ideas back and forth, then set to work. Zar glanced sideways at Vidar, then softly asked, ‘What’s a cartomancer, Dad?’

Dash shook his head, but Vidar looked up. ‘Well? Answer her question.’

It’s not illegal to know, I guess, Dash decided. ‘A cartomancer uses praxis to explore the world – specifically far-sight, foresight and earth magic – to determine the geological composition of a region.’

Zar’s eyes shone as she looked at their patient anew. ‘That’s a good thing, right?’

‘I suppose. But you have to remember, when they present their data to the empire, it usually leads to colonising invasions, the displacing of thousands of people to be exploited until they drop dead of exhaustion and kragging up the land for generations as they rape it beyond sustainability.’

‘Oh.’ Zar’s burgeoning admiration evaporated.

‘That sounds like Liberali talk, Cowley,’ Vidar growled. ‘The Imperium outlawed the old Liberali Party in Otravia nine months ago.’ He added, ‘They purged them with old-fashioned bloodwork.’

Gerda’s Tits, people I used to know . . .

‘I got out of Otravia years ago,’ he replied, adding, ‘in any case, I’m apolitical.’

‘There are no apolitical Otravians,’ Vidar snorted, then he sighed. ‘Look, Cowley, or whatever your real name is, I sympathise. My country’s been screwed over by the Bolgravs just as much as yours. So I’ll stop asking questions you don’t want to answer.’

They shared a more understanding look, then Dash turned to Zar. ‘Let’s get to work.’

They laboured for a couple of hours, cleansing and then cutting away infected tissue, before placing half a dozen leeches in the wound to suck up the infected blood. The cartomancer’s breathing stabilised, but that was the only good news.

I’m sorry, Cartomancer, but the chances are, you’ll never wake again. Dash hung his head, feeling that ache of not knowing enough, of not being enough. A real healer might have been able to save the cartomancer, but out here, knowing enough to cauterise a wound and sew up a cut made you the best physicker in the district. This was the western edge of the empire: the last place left to hide.

With a sigh, he plucked off the leeches, then mixed up a tonic, taking a moment to surreptitiously palm a tiny blue bottle and tip a drop into one of two clay cups. After he’d dosed the cartomancer, he pulled out a small keg and poured a thimble of amber fluid into each of the clay cups. He placed the tainted one in front of Vidar.

‘This is Urstian rye, best in Ferrea. Surely that’s worth some news?’

Vidar pushed the empty mug of claret aside, took the cup he was offered and downed it in one. Then he smiled. ‘Now that was good. Where’d you get it?’

‘From a trader in Falcombe, on the road here. Cost a fortune, because you just never see stuff like that out here: this isn’t Reka-Dovoi or Kortovrad.’

‘Tell me about it,’ Vidar snorted.

Dash poured another round and the ranger related his tidings: more failed rebellions in the Magnian heartland; more political assassinations and intrigues. ‘But we’ve been away over the Narrows for three months now, so I daresay it’s all changed,’ Vidar concluded, yawning.

‘A successful expedition?’ Dash asked.

Vidar chuckled. ‘Tell you that, I’d have to kill you.’

They chatted away amiably enough for another few minutes, then Vidarsson began slurring his words. ‘This rye . . . is . . . kragging strong, Cowley—’

‘Oh, Urstian rye’s a beast,’ Dash agreed. He smiled, waiting as the ranger deteriorated quickly, his head nodding, until he slumped and began to snore.

‘Gerda’s Blood, Dad, you just drugged him,’ Zar squeaked.

Dash went to the door and peered into the frigid night. The three Bolgrav soldiers were huddled over a blaze they’d made with his firewood. If these bastards hang round much longer we’ll be destitute again.

‘I want to read this cartomancer’s notes,’ he told Zar. ‘You get some sleep.’

He tousled her hair and they shared a fond, anxious hug; they’d been through a lot together and their bonds were tight but she’d clearly guessed that as soon as Gospodoi’s party were gone, they’d need to move again. If the Bolgrav gave their description to anyone with the wrong connections, the hunt would be on again.

Gerda knows where to next . . . There’re not too many other places to run, unless we leave the continent altogether . . .

Zar went back to her loft and he returned to the unconscious cartomancer and removed the satchel under his head. With half an eye on the drowsing Vidarsson, he opened the leather bag and removed the journal all cartomancers carried, and began to read. He was interested to see that while the older entries were in Magnian, which everyone could read, the later writings were in Ferrean, a standard subject in Otravian universities – but not in Bolgravia.

I’m fluent in Ferrean, but I bet Gospodoi isn’t. Most Bolgravs can’t be arsed learning other folk’s tongues. He read quickly, anxious to finish before his uninvited guest awoke.

I, Lyam Perhan, Imperial Cartomancer, do attest. In the year 1534ME, I accompanied Lord Vorei Gospodoi of Bolgravia on an expedition from Sommaport, across the Narrows, to the newly discovered land of Verdessa, which is claimed by Bolgravia.

The notes detailed navigational bearings, mineral readings and some sparse notes on flora and fauna. Perhan listed no native peoples, but he did mention a lake in the mountains at the edge of the Iceheart, the vast expanse of ice in the north. When Dash read the water analysis, one obscure chemical symbol, buried deep, leaped off the page.

Istariol . . . Gerda Alive, he found traces of istariol! And the readings hinted at far more: a lode bigger than anything discovered since the Mizra Wars. Dash’s veins tingled at the thought of what such a lode could do in the right hands – it might even revive the fight for freedom in Otravia and across the Magnian continent. The call of home flared up inside him, together with the burning need for revenge on the Mandarykes and all the other turncoats who let the Bolgravs into Otravia.

He skimmed the rest of the journal, finding no other references to istariol, but he judged that Perhan was wilfully obfuscating. The Ferreans have suffered as badly as the rest of us. Perhaps he didn’t want to tell Gospodoi what he’d found, so he buried the information in such a manner that it was more likely a friendly eye would see it . . .

He closed the journal and returned it to the satchel, then settled onto his pallet, closed his eyes and fell to dreaming of a glorious return to his homeland.

*

It felt like only minutes later when Zar shook him awake. ‘Dad,’ she murmured, ‘he’s waking – and the sun’s coming up.’

Dash looked up blearily and rubbed his eyes. He might not feel rested, but excitement was tingling in his veins. After too many years of exile the sense of opportunity was beckoning, but he kept calm as he washed his face, re-lit the fire and put water on the boil, keeping one eye on Vidar Vidarsson as the Norgan snuffled his way back towards wakefulness.

The cartomancer’s discovered enough istariol to start a war, but I’m almost certain he’s not told anyone else. So does anyone know about this find but him and me?

He looked across the room at Zar, seeing her mother’s face echoed there, and wondered if he had the right to drag her into one of his schemes. Let it pass, caution urged. Keep your head down. But the cartomancer’s journal was a treasure map. Letting such a chance pass by would tear him apart.

And what’s the alternative? To die in exile, while the Mandarykes ruin my homeland?

‘Zar,’ he asked, ‘if we had a chance to return home, you’d want to take it, wouldn’t you?’

‘Of course. I’m sick of being nowhere.’

He winced. She’d be at home right now if he hadn’t stolen her from her mother. But she’d be living at the whim of the Mandarykes and their Bolgrav friends, just like her mother, and they’d soon have taught her to despise me.

‘It’d be for us,’ he said, trying to convince himself as much as her. ‘For all we once had.’

‘I know, Dad,’ she said, throwing him a warning look as Vidar stirred again.

Still undecided, Dash signed her to put the conversation to one side. ‘Can you make us breakfast, please?’ he asked, before turning to the Norgan. ‘You all right there, fella?’

Vidar blinked awake, then peered at his empty cup. ‘Deo’s Balls, that stuff hits hard.’

‘Just relax, friend Vidar,’ Dash said. ‘I’m sure it’s been a trying journey for you.’

‘You have no idea,’ Vidar growled. ‘The number of times I came close to knifing those pricks. Arrogant bastards think they own the whole kragging world.’

‘They do: my land, your land, everyone else’s land. They’ve got the most powerful sorcerers, they’ve got the biggest armies and the most gold: the three pillars of empire.’

Vidar looked at him steadily. ‘Were you in Colfar’s rebellion?’

Dash winked and threw the Norgan’s words of the previous night back at him: ‘Tell you that, I’d have to kill you.’ They laughed, then he added, ‘We lost. There’s nothing more to say.’

‘Aye,’ the Norgan answered eventually. ‘I just pray that one day there’ll be a chance to strike back – a way that isn’t just throwing my life away.’

‘Don’t we all?’ Dash agreed.

The door swung open without warning, Dash flashed his hand to his dagger and spun round – to face a smug-looking Lord Gospodoi standing in the doorway.

The Bolgravian noble chuckled at the sight of bared steel. ‘Physickers take peace oath, ney?’

Dash sheathed his weapon. ‘Teshveld isn’t safe, even for a healer.’

‘Yuz, but maybe nowhere is safe for Physicker Cowley?’ Gospodoi mused, allowing his cloak to fall open: he wore a twinned rapier and dagger, the gems on the hilts worth more than all of Teshveld, not that that was saying a lot. He ambled into the hut and studied the unconscious Perhan. ‘How is patient?’

‘He’s alive, but I don’t think there’s much I can do,’ Dash replied, wondering how good Gospodoi was with his sword. ‘The infection’s gone too deep.’

Gospodoi tutted, as if chiding a disappointing infant. ‘I warned you,’ he said, reaching out and grasping Zar by the hair. ‘Maybe I make your daughter pay for your failings.’

‘I can’t do the impossible,’ Dash replied, keeping his voice subservient despite his hammering heart. The Bolgrav soldiers were now pressed around the door, sensing the chance of violence. ‘He was too far gone. You’re not being fair.’

‘Fair?’ Gospodoi snorted, jerking on Zar’s hair and making her squeal.

Then the Bolgrav laughed and let Zar go. ‘Just joke, yuz? Is funny, seeing man sweat over nothing.’ He put a hand on the back of Zar’s neck and asked, ‘So, you read Ferrean?’

Dash’s heart thumped, but he kept his expression frozen. ‘No one will harm my daughter.’

‘Of course.’ Gospodoi plucked the journal from the satchel under Perhan’s head. ‘You translate Ferrean words in this and all is well for you – and for little Zar-bird. Tell me about this “failed” expedition.’

Dash realised Gospodoi clearly suspected the cartomancer hadn’t told him everything. The empire doesn’t like failure, he thought.

So he took a deep breath, suppressed his worry about the threats to Zar, accepted the journal and retreated to his desk. His mind wasn’t on linguistics; he was trying to find a path he and Zar could walk that would allow them to get away unharmed.

‘Zar,’ he said firmly, ‘no one’s going to hurt you. Get up in the loft and clean up.’

‘Yuz,’ Gospodoi purred, ‘put nice dress on.’

Zar shot up the ladder like a polecat, jerking the curtains shut after her. Dash heard her crawl to the chest against the back wall and open it. He pictured her tossing clothes about in silent fury.

Then he focused on Vidar Vidarsson. His presence here might just provide the tipping factor. I can take one or two down, but not all these men – unless Vidarsson helps . . .

They’d made only the beginnings of a connection, but they shared the same view on Bolgravs, at least. So he threw the ranger a grin and said, ‘How’s your head, my friend?’ A plan began to form. He tapped the jug of rye. ‘You had a little too much moonfire last night?’

In most of Norgania and Otravia, the slang for istariol was moonfire.

Vidar’s eyes narrowed, then he stretched and stood. ‘Can’t ever get too much moonfire.’

‘What is this moon fire?’ Gospodoi enquired.

Dash handed him the jug. There was quite a bit of the rye left. ‘This.’

Gospodoi sniffed it, then deliberately dropped the clay vessel on the stone floor, shattering it and spraying the precious drink among the rushes. ‘I piss better drink than this,’ he remarked.

You kragging arsehole.

‘That’s a waste,’ Vidar muttered, his eyes glinting and the vein in his temple pulsing.

‘I can get more moonfire,’ Dash replied, discreetly tapping the diary, ‘from an old flame.’

Message received?

He awaited some sign, but beyond that throbbing vein, Vidar’s face was unreadable. Tension, or dislike for his employers? Whatever, I’m pretty sure he’s getting worked up.

Deciding he needed more solid confirmation, Dash put one hand behind his back where Gospodoi couldn’t see and traced a circle: Magnian finger-cant. Are you with me?

Vidar frowned.

Come on, man, are you in? Dash wondered. He thought they’d kind of made friends last night, even agreeing they’d both like to strike back against the oppressor. But I doubt either of us thought that would mean here and now.

Gospodoi went to the door and called in Bolgravian for his sergeant. Are they suspecting something? Dash worried as the sergeant came to the door and surveyed the small hut. Then he heard Zar moving above and glanced up.

‘Girl is up there,’ Gospodoi told the sergeant, this time speaking Magnian. ‘If there is problem, we punish her.’

‘Dad?’ Zar called from behind the curtain.

‘Make sure you’re properly dressed,’ Dash replied.

Tension settled like frost. Vidar went to the fireplace and warming his hands, said as if in afterthought, ‘Tell me about this old flame, Physicker.’

He gets it. Dash stopped himself sighing with relief. ‘Died of infection; there was nothing anyone could do. Then the damned nobles came in and took everything.’

‘Too much you talk,’ Gospodoi said. ‘Stop now and read journal.’

Dash obediently began, ‘I, Lyam Perhan, Imperial Cartomancer, do attest—’

‘Ney, ney,’ Gospodoi said impatiently, ‘go to water readings, last entry. Tell me.’

Dash tapped a finger, thrice in quick succession, then twice, then once—

—and moved: his hand flew to the hidden dagger in the scabbard tacked to the underside of the desk, he drew it and thrust it into Gospodoi’s kidneys, shouting, ‘Now, Vidar!’

Gospodoi convulsed in shock as the blade penetrated – but Vidar just stared, his mouth falling open, and Dash realised that the ranger hadn’t understood any of his cryptic messages at all.

Shansa mor! ‘Move!’ he barked at the Norgan.

At the doorway, the big Bolgrav sergeant stood frozen, just as stunned – no one was ever stupid enough to attack a Bolgrav lord like this. But the two soldiers behind him were yelping and flailing for their weapons.

‘What the—?’ Vidar gasped.

‘Jou—’ Gospodoi grunted, reaching for his pistol, but his legs went and instead he staggered against the table.

The sergeant finally wrenched out his sword, but wavered, unsure whether to go for Dash or Vidar.

‘Kragga!’ Dash exclaimed, ripping his dagger sideways out of Gospodoi’s belly, which sent blood spraying an arc across the room. The nobleman collapsed into the fireplace, sending ash and sparks spitting everywhere. The flames quickly took hold of his clothing and as they blazed into life, he shrieked.

The Bolgrav sergeant made his decision: he raised his longsword and swung at Vidar – and the blade caught in the low rafters.

Vidar gaped at the blade, then at the sergeant, and now the pulse on his temple was really hammering.

Then he snarled.

Outside, the soldiers were shouting and waving their flintlocks around, but as they hadn’t fired at anyone yet, Dash guessed they weren’t loaded. But one had had the sense to ram a bayonet onto the muzzle and he burst through the doorway, lunging at the Norgan.

And still Vidar hadn’t moved . . .

Then Dash suddenly realised this wasn’t the paralysis of fear, but something deeper: Vidar’s eyes blazed with amber light, then his spine twisted and he hunched forward, hands splaying as he vented a bestial roar. He battered the bayonet aside, then drove his fingers – no, there were two-inch claws bursting through his nails – into the man’s throat and ripped.

Dash stared. Kragga mor, he’s a bearskin!

The soldier collapsed in a haze of spraying blood as the second man appeared at the door with a loaded flintlock. He saw Vidar standing over his dying comrade and took aim – as the curtain in the loft jerked aside and Zar appeared, cradling a crossbow. With a sharp thunk, she discharged the weapon and the bolt slammed straight into the gun the soldier held, which jolted and roared flame. The lead ball pinged off the floor and lodged in the wall six inches from Dash’s head, but he was already spinning and hurling his dagger, which buried itself in the man’s left shoulder, sending the gasping Bolgrav staggering backwards.

With a furious roar, Vidar went at him, a six-foot leap that bore the soldier down. His teeth – now long, savage fangs – snapped closed in the man’s neck. Vidar wrenched, the neck snapped and the soldier went still. But Vidar continued t

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...