- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

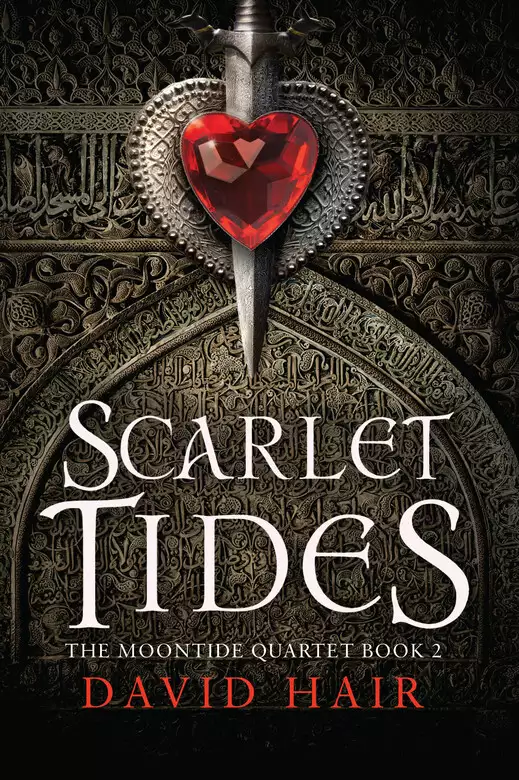

The Moontide has come and the Leviathan Bridge stands open: now thrones will shake and hearts will be torn apart in a world at war.

A scarlet tide of Rondian legions is flooding into the East, led by the Inquisition's windships flying the Sacred Heart, the bright banner of the Church's darkest sons. They are slaughtering and pillaging their way across Antiopia in the name of Emperor Constant. But the emperor's greatest treasure, the Scytale of Corineus, has slipped through his fingers and his ruthless Inquisitors must scour two continents for the artefact, the source of all magical power.

Against them are the unlikeliest of heroes. Alaron, a failed mage, the gypsy, Cymbellea, and Ramita, once just a lowly market-girl, have pledged to end the cycle of war and restore peace to Urte.

East and West have clashed before, but this time, as secret factions and cabals emerge from the shadows, the world is about to discover that love, loyalty and truth can be forged into weapons as strong as swords and magic.

"Hair tells his story with aplomb in a clear and concise prose.... Mage's Blood is one of the better [epic fantasy] first installments I've read in recent years." -staffersbookreview.com

Release date: October 7, 2014

Publisher: Quercus

Print pages: 688

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Scarlet Tides

David Hair

The Vexations of Emperor Constant (Part Two)

The Imperial Dynasty

The Blessed Three Hundred, though reveling in their godlike powers and fresh from destroying a Rimoni legion, were cast into confusion by the death of their charismatic spiritual guide Johan “Corineus” Corin. His murder at the hands of his sister, Corinea, had horrified his followers, and left them with an immediate problem: who would succeed the man who had bequeathed them the gnosis?

But Ganitius, Corineus’s loyal “fixer,” and Baramitius, whose potions had opened the gateway to the gnosis, acted quickly to ensure the future of the group. Uniting behind the nobleman Mikal Sertain, they established a new leadership that saw Sertain anointed Corineus’s successor, the successful destruction of the bewildered Rimoni armies, and the installment of the Sacrecour dynasty that still rules Pallas and the empire today.

Why Sertain? Because his family were well-moneyed.

Ordo Costruo Collegiate, Pontus

Pallas, Rondelmar

Summer 927

1 Year until the Moontide

One year until the Moontide. It seemed like no time at all.

Gurvon Gyle studied the faces about him anew as they settled back into their seats. Over the last hour, the atmosphere of the room had changed. His plan for the conquest of Javon had been agreed, but that was just the first step. The rest of this meeting would be more contentious, and test the ability of this group of people to work together. He smoothed the sleeve of his rough dun-colored shirt, wondering if his plans for Javon would go as intended.

When does anything ever go as planned?

To his left, fellow Noroman Belonius Vult, Governor of Norostein, was riffling through his notes as he prepared to speak again. He was clad in the finest cloth, of silver and blue. His noble visage spoke of wisdom and secret knowledge, like some legendary guide to the future; appropriate, Gyle thought, as their plans were set to shape the world for years to come. Five others shared the meeting chamber deep within the Imperial Court in Pallas: the four men and one woman were all Rondian, and among the most powerful people in the known world.

It was only natural to look first at the emperor. He was a young man still. Though he ruled the greatest empire in history, the crown did not weigh easily upon his brow and he looked shrunken in his glittering robes. He was sour-faced, with flawless pale skin and wispy facial hair, and his nose twitched constantly as he looked about him, as if he imagined himself surrounded by enemies. As well he might: he had ascended after the premature death of his father and the incarceration of his elder sister. Intrigue festered in his court.

The emperor’s nervous eyes were drawn most often to the woman at his right hand: his mother. Mater-Imperia Lucia Fasterius-Sacrecour did not look frightening, but it was her machinations that had brought her favorite—and most pliable—child to the throne of Rondelmar. With a serene face and simple taste in clothing, she was outwardly the picture of a devout and matronly woman. Yesterday, in a vast ceremony before the massed populace of Pallas, she had been made a Living Saint, but no one then had seen any sign of her chilling and callous intellect. Gyle had witnessed enough evidence of her ruthlessness to know that her approval alone would see the second part of the plan accepted.

And we will need her favor even more urgently if anything goes wrong.

The man who had invested Lucia as a saint, Arch-Prelate Wurther, sat opposite Gyle, swirling his wine and looking about contentedly. He met Gyle’s eyes and smiled amiably. The prelate looked harmless enough, like a parish priest promoted past his capability, but he was a wily old hog. The Church of Kore was no place for fools.

Next to the prelate, the Imperial Treasurer Calan Dubrayle was leaning back in his chair, eyes unfocused; mentally counting money, perhaps. He was a slim, dapper man with careful eyes. He’d been appointed Treasurer following the ascension of the emperor; his analytical mind and head for the gold that flowed through the coffers of Urte’s mightiest state made him perfect for the job.

Gyle had no love for either of the two men talking in the corner. When his homeland had revolted against the empire eighteen years ago, he and Belonius Vult had been part of that rebellion. Kaltus Korion and Tomas Betillon had been the generals who’d eventually crushed the uprising—and now here they all were, part of a fresh conspiracy, the Noros Revolt forgotten. Except it wasn’t, not really. You didn’t forget things like that, no matter how many years had passed.

Kaltus Korion looked like a hero, and was, to the man on the street. His pale hair was swept back from a strong face, framing steely eyes and a jutting jaw. His combative manner only heightened the heroic illusion. The man with him—burly, uncouth Tomas Betillon—swilled wine as he tapped Korion on the chest, making some point.

Neither will like the next part of the plan, Gyle thought.

He rubbed his thumb and forefinger together, invoked his gnosis and bled a little heat into his red wine to combat the chill in the room. All eyes went to him as he did it: everyone else was a pure-blood mage and highly sensitive to any use of the gnosis. He opened his hand palm-up, to indicate that what he’d done was no threat.

Mater-Imperia Lucia inclined her head to him gracefully, then called to the two military men, “Kaltus, Tomas . . . I believe Master Vult is ready. We await your attention.”

Korion and Betillon stalked back to their seats. Korion’s low grumbling quieted only when Lucia narrowed her eyes. The Living Saint glanced down at her papers, then around the table. “Gentlemen, in twelve months the Third Crusade begins, giving us the chance to achieve certain of our objectives. Among them, the destruction of the merchant-magi cabal; the death of Duke Echor of Argundy—the only real rival to my son; the destruction of the Ordo Costruo and Antonin Meiros; the plunder of northern Antiopia and subsequent enrichment of our treasury, and the recapture of Javon. Magister Vult and Magister Gyle have invested much time and thought and we’ve already covered the Javon problem.” She turned to the two Noromen. “That aspect of your plans already has our approval.” She looked at Vult. “So, with my son’s permission, Governor, please continue.”

The emperor inclined his head distractedly, not that anyone really noticed.

Belonius stood and thanked her and then began, his clear voice easily filling the room, “Your Majesties, gentlemen. According to our plans, Javon will be paralyzed and unable to support the shihad by the time the Moontide arrives and the Leviathan Bridge rises from the sea, thus securing the northern flank—and our supply lines—for the armies of the Crusade. This leaves us free to turn our attention to other things, namely the destruction of the enemies of the empire. As Mater-Imperia Lucia has outlined, many of those are internal enemies. You’ve all seen the documents Gurvon provided before the meeting. They prove not only that Duke Echor Borodium, the emperor’s own uncle—and outwardly a strong supporter—has been in contact with the emperor’s disgraced sister Natia, but that he has made approaches to the governors and domestic rulers of all of the empire’s vassal-states on her behalf, canvassing their support. These are treasonous acts worthy of death. But the fact remains that Argundy is the second-largest kingdom in the empire. When Echor’s brother conspired with the emperor’s sister and was executed, Echor was not in a position then to prevent that, or take the field in her name, but his resentment remains strong, and now he is in control of Argundy—”

“We should have killed him when we had the chance,” the emperor grumbled, making a face. “When he was kneeling before me, kissing my signet, and pleading for his brother’s life, I should have seized an ax: chop chop!” He sniggered at the mental image.

Gyle saw Lucia’s eyes tighten just a little: impatience, tempered with a mother’s indulgence. “Darling, you remember that was impossible,” she chided him gently. “Echor has married into the Argundian kings. Beheading him would have guaranteed revolt at an inopportune moment. Buying him off bought us time to deal with him. That time is now.”

Constant’s nostrils flared at her tone, but he ducked his head and fell silent.

Belonius breezed past the interruption. “To weaken Echor’s standing, we need to lure his vassal-state allies to destruction. We need them to join the Crusade. The Second Crusade yielded inadequate plunder and all but destroyed trade. The vassal-states claimed they had emptied their treasuries to fund it and got nothing back, and because of that, they would not support any more Crusades in the future.”

Betillon scowled contemptuously. “If they’d committed more troops, they might have—”

Unexpectedly, Calan Dubrayle broke in. “No, actually, Magister Vult is quite right: the Second Crusade was a waste of money. The Sultan of Kesh is not stupid. In the preceding years he and anyone with wealth shipped their gold and riches eastward, far from our reach. They also poisoned waterholes and burned their own crops for hundreds of miles inland. We spent millions marching our armies all the way to Istabad and recovered—what, a third of our outlay? By the time I’d taken the emperor’s share and the Church’s, the vassal-states were left with nothing.”

You might have added another group, Treasurer: the noble magi who robbed their soldiers to enhance their own coffers. They took as much as the Imperial Treasury and more.

“You say that as if it were a bad thing,” Betillon chuckled. “Keeping the provinces weak is half the battle.”

“Maybe,” Dubrayle noted, “but it doesn’t leave much enthusiasm for more Crusades.”

Vult coughed to regain the floor, and went on, “Argundy, Bricia, Noros, Estellayne, and Hollenia have all said they will not join this Crusade.”

“Noros,” Korion snarled, jabbing a finger at Vult. “If your people don’t join the Crusade in their thousands, I’ll give them another crackdown that will make Knebb look like a holiday.”

Betillon laughed harshly: he’d been the Rondian general to order the slaughter at Knebb during the Revolt. He was still known as “The Butcher of Knebb.”

Gyle still remembered entering the smoking ruins of the town and seeing the carnage for the first time. Something inside him had changed forever that day. For now, he worked hard to keep his expression carefully blank.

“I will demand their participation,” whined Emperor Constant. “They’re my subjects.”

“Darling,” Lucia chimed in, smiling sweetly, “even dogs have to be fed or they become unmanageable.”

“Our Beloved Mater-Imperia is wisdom itself,” Vult put in quickly. “The Crusade needs the manpower of the vassal-states. Every province of the empire must participate.”

“Why?” Korion demanded. “Rondelmar must control the action in Antiopia when the time comes, and that means dominating the military. We’re only one third of the empire’s population: if every state sends every eligible soldier, we will be outnumbered. If Echor were to unite them, we would be overwhelmed.”

“But my lord,” Vult countered, “during the Second Crusade, the armies of the vassal-states were in Kesh and therefore, they were not here. They were grubbing around for loot as desperately as we were. The circumstances have changed now: they don’t want to go. If they hold back and Rondelmar sends all its troops into Antiopia for two years, who will stand up to Echor?”

“He wouldn’t dare,” Constant said, outraged. “He bowed to me! He kissed my ring!”

Kissing your ass doesn’t mean he loves you, Gyle thought.

Silence greeted the emperor’s declaration, but Gyle saw Mater-Imperia Lucia’s eyes narrow again.

“Magister Vult,” said Arch-Prelate Wurther, “you say that getting the vassal-states to commit to the Crusade is vital, but if we do that, how will we control them? More important, how will we ensure that the plunder finds its way to the proper places? Your notes on this matter were frustratingly vague.” The prelate wagged a finger admonishingly.

“Their commitment is paramount,” Vult replied. “If Echor and his allies are not in the vanguard of this Crusade, then a domestic coup while the Crusade is in progress is inevitable.”

“Rondelmar has all the strongest magi,” Korion countered. “A Pallas battle-legion is worth at least three from the provinces. They would not dare.”

“Actually, that is not entirely true,” Calan Dubrayle put in mildly, again taking Vult’s side, making Gyle wonder what was in it for Dubrayle. Maybe he just likes annoying Korion? “The most recent census revealed that more than half of all magi live outside of Rondelmar. Most of the strongest are here, it is true, but numbers matter. And the loyalty of those within is not to be taken for granted,” he added.

Emperor Constant’s mouth fell open and his eyes went to his mother’s face as if for reassurance. “My people love me,” he squeaked. “All of them.”

Yes, yes, they kissed your rukking ring. But some love Echor and others love your poor, tragic, imprisoned elder sister and they all wonder whether your ass on the throne really does represent the will of Kore.

“Carry on, Magister Vult,” Lucia instructed, silencing her son with a warning look.

“The Treasurer is correct: a ruler must always be vigilant. Our emperor is a paragon of all the virtues; lesser men have baser morals.” Vult made a subservient gesture to Emperor Constant, then to Lucia. “I therefore propose that we make a public concession, one that will ensure that we get all of the zealous manpower we could want from the vassal-states and at the same time put the heads of our enemies firmly in the noose: we offer Echor command of the Crusade.”

“What?” Kaltus Korion leaped to his feet, exploding with fury. “That isn’t in your notes! Who the Hel do you think you are? It is my right to command the Crusade!”

“General Korion!” Lucia’s voice cracked like a whip. “Sit down!”

“But—” Korion looked set to shout at her, and then abruptly swallowed his words. “Your Majesty, I apologize,” he said, trying to calm himself. “But I don’t understand; I am the Supreme General of the Rondian Empire, I must lead the Crusade.” He struck his own chest, over the heart. “It is my due.”

Gyle watched Korion thoughtfully. Plunder the East, return with all the loot, with a massive adoring army at your beck and call . . . Perhaps you’re eyeing the Sacred Throne yourself, General?

“You’re still standing in our presence,” Lucia reminded the general in a voice that dripped acid. “Sit down, Kaltus, and let us debate this like adults.”

Korion stared at her for half a second and then sat, abashed.

Gyle looked at Vult. Interesting.

Emperor Constant looked puzzled. He obviously didn’t understand what was going on. Betillon looked as outraged as Korion. Dubrayle and Wurther were expressionless, which seemed exceedingly wise.

Mater-Imperia Lucia tilted her head to Vult. “Continue, Magister.”

Vult took a breath. “Thank you, Mater-Imperia,” he said, emphasizing her title as if that might deflect some of the fury that was radiating from Kaltus Korion. The two men had hated each other since the day Vult had betrayed the Noros Revolt by tending his surrender to Korion.

“It is my command, turncoat,” Korion told him in a low voice.

Vult flushed angrily. “The future of this empire is at stake. This is not a time to think of one’s personal standing. This is a time to reflect on how one can contribute to the greater good.” His eyes focused on some imaginary point halfway between Korion and Mater-Imperia Lucia. “This is a time to put the well-being of our emperor first.”

“Hear, hear,” said Wurther, sipping wine with a twinkle in his eye, earning him a belligerent glare from Betillon, which troubled the Churchman not at all.

“The common people, the merchant-magi, and even many of the loyal magi spread throughout the empire do not wish to see another Crusade like the last. They were promised the world, my lords. They were told to expect plunder beyond all dreams, that the East was awash with gold. And I believed that too, as firmly as any.”

Gyle knew Vult’s financial situation. The Governor had invested heavily in the Crusades and lost.

Vult continued, “Argundy, Bricia, and Noros are from the same stock as Rondelmar, yet they balk. The people of Schlessen, Verelon, Estellayne, Sydia . . . they refuse involvement outright. Last time they invested men, money, and stores, and they lost all but the men. They slaughtered heathens by the thousand, but what did they gain? Nothing—Pallas took it all. Why would we march again? Why?”

We? Gyle smiled to himself, then caught Lucia watching him. She raised an eyebrow but said nothing.

Vult tapped his papers. “Only one thing will bring the provinces into this Crusade: the belief that this time will be different. And only one thing can send that signal: the leadership of this venture being given to the man they associate with balancing the power of Pallas with that of the provinces: Duke Echor of Argundy. Appoint him, and the provinces will join. Fail to do so, and you may as well prepare to man the entire Crusade on your own.” He didn’t say “if you can,” but those words hung in the air.

The room fell silent. Korion and Betillon exchanged a glance as if daring each other to protest. Constant still looked childishly confused, but the others were catching on: Lucia wants this. It will happen.

Korion stood, and Gyle watched the man swallow his pride as he addressed himself to Lucia. “Mater-Imperia, I apologize. This plan is wise. A military commission is nothing when compared with the perpetuation of the might and majesty of the House of Sacrecour.”

No one had ever called Kaltus Korion stupid.

The same could not be said for Tomas Betillon. “I don’t understand,” he grumbled. “Let the proclamations go out, see how many sign up first, before we commit to something we don’t need to.”

“And be seen to back down?” Dubrayle asked caustically. “I think not. An emperor states a path and does not deviate. He does not negotiate with his subjects: he just makes sure his proclamations are realistic and enforceable.”

“There’s another thing,” Gyle threw in, as if it had just occurred to him. “You have the battle-standards of the Noros legions in your hands, and many from previous rebellions in Argundy and other provinces. Give them back.”

Korion’s jaw dropped. “Fuck you, Noroman. I keep my trophies.”

“If the battle-standards are returned, men will flock to enlist,” Vult chimed in. “They will see themselves as forgiven. It will give them back their pride, and give them a reason to forgive the empire.”

“Forgive?” sneered Constant. “I taught them a lesson in the forgiveness of the empire: there is none!”

You taught us, did you, your Majesty? Gyle thought. Was that how it was? I understood you spent most of the Noros Revolt cowering in fear of assassins like me.

“It is but the misguided perception of the common man,” Vult replied smoothly, “but these feelings persist.”

The emperor’s mother stroked her son’s arm and whispered something in his ear. The emperor nodded slowly. “My mother reminds me that the people of Noros are yokels. We are fortunate to have two such rarities as yourselves able to attend upon us without chewing grass and stinking of cow shit.”

Betillon smirked. No one else moved a muscle. The moment stretched on.

Well, that shows us the true extent of our welcome. Gyle turned slightly. Out of the corner of his eye he watched Belonius, apparently impervious to the insult. But then, he probably shares Constant’s assessment of his own people.

“The suggestion is an excellent one,” Mater-Imperia Lucia told the room. “The provinces know who their masters are. Rubbing their noses in it is counterproductive. Give them Echor in charge and their battle-standards back, and they will enlist in droves.”

“They’ll outnumber us in Kesh,” Korion reminded her.

“Not significantly. And once there, I am quite sure you will turn it to our advantage.”

“How?” sniffed Korion. “There’s no one to fight. We hear the Amteh priests have declared some sort of holy war but, realistically, they’ve got no magi, no constructs, and no discipline. Crusades aren’t wars, they’re two-year treasure-hunts.”

Lucia permitted herself a small smile. “To which Magister Gyle has a response.” She made a welcoming gesture. “Our guest awaits.”

“Our guest?” chorused Korion and Betillon in mutual exasperation.

“This is the Closed Council,” Constant whined, “not the tap-room of a tavern.”

Gyle ignored him, rose and walked to the door. He tapped, and the guard opened it. He breathed deeply as he went into the antechamber, inhaling fresher air. They’re like squabbling children, not leaders of men. They’ve no vision, no plan. It’s all just pettiness, self-interest and boasting.

Except Lucia. Her, I could follow.

The man waiting in the antechamber was robed in black with heavy furs draped about his shoulders, despite the summer heat. He dropped his hood and stood as Gyle entered the room. With his dark coppery skin, jet-black hair pulled tightly back from his face, and a neatly trimmed beard and mustache, he was both striking and alien. His eyes glinted like emerald chips. Rubies adorned his ears, and a diamond periapt hung about his neck.

“Emir,” Gyle said, striding forward. “I trust you are well?”

“Magister,” Emir Rashid Mubarak of Halli’kut purred in welcome. He embraced Gyle courteously, kissing both his cheeks and patting his back in the space between the shoulder blades. In Kesh that was a gesture of reassurance—see, I could kill you, but I do not. Rashid was officially the fourth-ranked mage of Antonin Meiros’s Ordo Costruo, a three-quarter-blood descended from a pure-blood and a half-blood mage. His half-blood mother had been the child of a pure-blood who had married into a Keshi royal line before Meiros’s Leviathan Bridge was even completed. Her son was the result: a polished gemstone of a man, finely cut and glittering. “I am deathly cold. How do you stand it?”

“This is summer, my lord. I advise you to depart before it snows.”

“I shall be leaving immediately afterward. How goes the meeting?”

“Well enough,” Gyle said. “Constant is in a sour mood. Address yourself to Lucia and ignore the idiocy from Korion and Betillon.”

“Tomas Betillon is well known to me. I am practiced in dealing with him.” Rashid shrugged. “What is that word you use for us: barbarian? He is that, I am thinking.”

Gyle glanced at the guard, who was staring at Rashid as if he were a construct beast of unusual strangeness, and suppressed a smile. “He surely is.” He gestured toward the door. “Shall we go in?”

Vult met them at the door. “Ah, there you are.” He inclined his head toward Rashid.

The Emir bowed. “It is my great pleasure to meet you at last. Magister Gyle has told me so much of you.”

Vult’s mouth twitched with humor. “Nothing bad, I trust, Gurvon?”

“Only the truth, Bel.”

“Oh dear. Well, Emir, you came despite that. We are about to discuss your role in our plans. Come in, my friend.”

Rashid paused. “Do not mistake me for a friend, Magister Vult. I am far from that.”

Belonius Vult smiled smoothly. “We have enemies in common, Emir. That is the strongest form of friendship I’ve ever known.”

1

How You Meet Your End

The Rune of the Chain

The ability to lock up a mage’s powers is unfortunately required. Though we are all descendants of the Blessed Three Hundred, some among us are unworthy of that lineage. To cut off a mage from their great gift is a drastic step, not easily or lightly done. The sad truth, however, is that villainy does manifest among us, and is magnified by our capacity for harm.

Marten Robinius, Arcanum Magister, Bres

Norostein, Noros, on the continent of Yuros

Julsep 928

1st month of the Moontide

Jeris Muhren, Watch Captain of Norostein, descended the clockwise-curving stairs. The darkened stairwell was narrow, damp, and treacherous. A dank, stale smell rose from below, along with the clank and clatter of stone and steel. It was early morning on a summer’s day outside, but winter’s cold still lurked in the dungeons of Norostein’s Governor’s Palace. There were no guards down here, unusually. Their absence made him wary, and he loosened his sword as he strode on.

He pushed open the door at the bottom of the stair and entered a small chamber, where he was surprised to find another before him: a youngish-looking man with a weak chin partially hidden by a wispy blond beard. His thin body was draped in heavy velvet robes and a gold band encircled his worry-creased brow.

Muhren hastily dropped to his knee. “Your Majesty,” he murmured. What’s he doing here?

“Captain Muhren,” King Phyllios III of Noros responded formally. “Please, stand.”

Muhren rose, puzzled. Phyllios III was a puppet ruler, with the governor’s hand firmly up his ass—at least, that was the word on the street. The failed Revolt had broken the Noros monarchy, leaving the king a powerless sideshow in a decrepit palace. The Governor ruled Noros now, in the name of the emperor—but right now that same Governor was a prisoner in his own dungeons.

“My King, you should not be here.”

Phyllios shrugged lightly. “The guards were ordered away an hour ago, Captain, and no one saw me arrive. I am not so confined to my palace as you might think.”

Muhren blinked. Last day on the job and I’m still learning.

“How is our prisoner, Captain?” the king asked. His voice was tentative, but there was a certain vengeful cunning Muhren had not heard before. Phyllios had been a young man during the Revolt, when he had seen his people crushed. The Rondians made an example of him, forcing him to become a parade attraction: he had been flogged naked before his people before being forced to crawl before the emperor and beg forgiveness. That had broken whatever manner of man he might have become and turned him into a powerless cringer—at least, so Muhren had once thought. Appointing the watch captain was one of the very few prerogatives left to the king and Muhren had been Phyllios’s choice. That pact had revealed a stronger man than most knew, but he was still very cautious, even timid.

“He is deeply unhappy, my liege. Cold, uncomfortable, and very much afraid.”

“Of whom? Surely not you or me.” Phyllios’s tone was self-mocking, but not self-pitying.

“Of the Inquisition, my liege.”

“Inquisitors are coming here?” Phyllios’s calm wavered.

“Inevitably, my liege. He’s an Imperial Governor, arrested for treason. They will most certainly be here in days, and they will take him away and break him in the process of deciding whether he is guilty of anything. The emperor cannot afford to permit any governor to appear to be acting beyond his authority.”

Phyllios nodded gravely. “What will they learn from him, Captain?”

Ah, now that is the question. I don’t care about anything else they might learn, but they will inevitably find out about Alaron, Cym, and the Scytale, and my own role in those events. And then all Hel will burst free.

But for your own safety, I can’t tell you this, my King. Muhren had ransacked the governor’s offices, to give himself a legitimate reason to arrest and imprison Vult in the aftermath of the struggle to reach the Scytale. Now he lied to his king. “There was nothing altogether startling in what we found, my liege, just evidence of the usual corrupt games men like Vult play. Cronyism. Backhanders. Illegal interests. Nothing that will rebound against the throne.”

“How many people know he is here, Captain?” the king asked.

“Too many, my liege.” Vult’s arrest had been carried out with the help of a squad of soldiers on the outskirts of the city; that had been unavoidable. Muhren wasn’t naïve enough to believe they would stay silent on the matter, especially as they had brought back two more bodies, Vult’s accomplices, and buried Jarius Langstrit in a secret grave.

“Do you wish him to be questioned, Captain? By the Inquisitors, that is.” Phyllios’s eyes narrowed with a shrewdness he seldom displayed in public. “Is there aught he might say that would imperil you?”

Muhren hesitated. That’s the thing, isn’t it? “A trained Inquisitor can learn anything there is to learn, my liege. From anyone. If they decided there was something to be learned, they would question anyone connected.” He met his king’s eyes.

Phyllios nodded slowly, hinting at an astuteness few would have credited him. “I will miss you, Muhren. You’ve served Norostein well. I’ll not find another like you.”

Muhren bowed his head, suddenly feeling emotional. He’d put his heart and soul into the Norostein Watch, but the king was right: he had to be gone before the Inquisitors arrived. “I will ensure no trail leads back to you, my liege. And I will be gone by sunset.”

“Farewell, Captain.” Phyllios reached out and patted Muhren’s arm, the closest to an affectionate gesture that Muhren had ever seen from

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...