- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

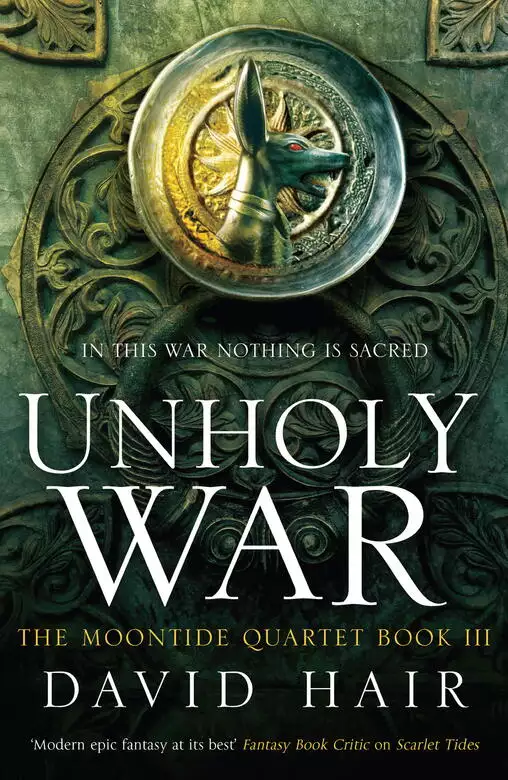

Unholy War, the penultimate volume of David Hair's Moontide Quartet, sets the stage for the series' impending conclusion. Fanboy Comics compares it to "great fantasy epics such as A Song of Ice and Fire and The Wheel of Time, and it easily earns its place amongst them."

Tensions are mounting after a devastating battle before the walls of Shaliyah, birthplace of the Prophet. The East is rising, bringing equal measures of hope and despair to the magical world of Urte.

For some Salim's victory is a call to arms, for others it is evidence of a world gone mad. While the armies of East and West clash in brutal conflict, emperors, inquisitors, Souldrinkers, and assassins all have their attention turned elsewhere as they hunt the Scytale of Corineus. The immensely powerful artifact is the key to ultimate power, and it's in the hands of unlikely guardians: failed mage Alaron Mercer and market-girl Ramita Ankesharan, who carries the child of the world's greatest mage. The fate of the world hinges on destruction should the artifact fall into the wrong hands.

Release date: October 30, 2014

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 688

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Unholy War

David Hair

PROLOGUE

The Rimoni Empire: Emperors

It was many centuries before Rimoni could dare to call itself an empire, and the transformation from republic to empire was bloody and almost disastrous. The lesson it taught: court power as you would court a lover.

THE RIMONI EMPIRE: A HISTORY, ARNO RUFIUS, LANTRIS 752

Pallas, Rondelmar

Summer 927

1 Year until the Moontide

Gurvon Gyle let his gaze drift around the room while his countryman Belonius Vult restated the plans for the invasion of Kesh and the entrapment and destruction of Echor Borodium, Duke of Argundy, and his army. Two Noromen who’d risen against the emperor only seventeen years ago, sitting in that same emperor’s inner sanctum and presenting him with a plan to cement his rule. Who would have imagined such a gathering?

Emperor Constant had been just a child then, and perhaps a life in the shadow of more powerful figures had undermined him, made him the weak-kneed young man he was now, startled by shadows and afraid even of those closest to him. The weight of the crown furrowed his brow and hunched his shoulders. Every few seconds he glanced at his mother, as if seeking approval.

Yet if what we’ve just outlined works, we’ll have destroyed a man who’d make a far better ruler and widowed a quarter of a million of his people – and all in your name, Constant Sacrecour.

It was Mater-Imperia Lucia who dominated the room. She had never needed eye-catching beauty; her sheer presence and veiled intensity were sufficient. Her matronly face was a study in concentration as she listened to Vult, but her eyes roved continually, noting reactions, filing away the tiny behaviours of everyone present. Her attention wasn’t on those familiar to her – iron-faced Kaltus Korion, who was to take over the command of the Crusade next year when Echor died; Tomas Betillon, who would troubleshoot the inevitable crises behind the lines; Calan Dubrayle, who would be safe here in Pallas, counting the profits, and Grand Prelate Wurther, who would be wherever the food was. She was studying Vult, and Gyle himself too; occasionally their eyes met, appraising each other.

Mostly though, her eyes were on the newcomer: the alien. The enemy.

Emir Rashid Mubarak of Halli’kut was quite likely the first Keshi ever to enter this room. In contrast to the dour formality of Rondian courtiers, when he’d removed his cloak it had been as if a peacock had unfurled its tail-feathers: his clothes were almost gaudy, with glittering gems woven into the fabric that were nearly as bright as his own mesmerising green eyes. He reminded Gyle of a cobra swaying to a snake-charmer on the streets of Hebusalim.

Rashid had listened patiently, asked good questions, then he had allowed them to question him. He answered with practised ease, replying to some, not all. Most were logistical: could he field an army big enough to destroy Echor’s? How many magi did he have? Was he sure he could overcome Meiros’ faction within the Ordo Costruo?

The emir didn’t give any definitive answers, of course, and Gurvon would have been surprised if he had. They were not allies; just enemies in collusion. Nor did the Rondians tell him all their plan, just the part he needed to know so that he could deploy overwhelming forces against the Duke of Argundy during the crusade. Echor would have inexperienced soldiers and weak-blooded magi, and was travelling into the most inhospitable deserts of the east. None of the Rondians showed concern that Rashid was any threat to the real army – Kaltus Korion’s forces, who would have the best of everything and were nigh-on invincible.

And after that …

Gurvon smiled grimly.

… then the rest of our plan unfurls. Dhassa, Kesh and Javon would become states in thrall to Pallas for ever, and provide the staging-ground for the full conquest of Antiopia. Rashid’s destruction of Echor would be forgotten, except in Argundy itself, where its weakening effect would prevent any possibility of revolt for generations to come. Emperor Constant would become ruler of the known world.

Belonius Vult concluded the discussion with his trademark flourish and turned towards the throne, seeking imperial assent. Constant glanced sideways at his mother as usual before inclining his head. Rashid noticed, of course: a little intelligence of his own to take home: that the Emperor of the West’s hands were tied up in apron-strings.

‘Emir Rashid,’ Lucia said, ‘do you have any questions of your own?’

The emir bowed his head slightly. ‘None at all, lady. The magus has been most clear.’ His voice had a music that would have beguiled one of Kore’s nuns.

‘You do not find it strange that we would act against our own?’ Lucia asked lightly.

Rashid smiled. ‘Let me tell you a tale of my own family. My grandfather once invited his brothers and cousins, all those with a claim to the throne of Halli’kut, to a great feast. He lavished them with gifts and sweet things for a week. On the final night, having allayed the fears of even the wariest, he released ten thousand serpents he had collected for the purpose into the sleeping chambers. He wiped out his entire family, except for his immediate kin, and so secured his reign.’

Gurvon saw looks of sceptical disdain creep across Korion and Dubrayle’s faces. Betillon was looking appreciative – his own ruthlessness ran just as deep. For himself? It just seemed wasteful. He could have found more elegant solutions to such problems, he was sure. As for Lucia … it was as if she recognised a kindred spirit.

‘How will your people greet victory over Duke Echor?’ he asked Rashid.

Those emerald eyes met his own. ‘With great rejoicing.’

‘It will be your only victory,’ Korion warned.

Rashid smiled faintly. ‘All know your reputation, General Korion.’

‘Then don’t be deluded by the crust we throw you and think you can repeat the feat without our connivance,’ Korion snapped, his mouth was shaping the insult ‘mudskin’, but he had the sense to leave to it unspoken. Rashid was a magus himself, one of a handful of Keshi-blooded magi who were part of the Ordo Costruo, the heretical magi based in Antiopia. Rashid was a three-quarter-blooded mage, and though all present in this room had the gnosis, Rashid was a renowned practitioner of the art.

‘The war will unfold as Ahm wills,’ Rashid responded mildly. ‘We will destroy your enemy the Duke of Argundy, and then all cooperation is over. What will be, will be.’

‘As it should be,’ Lucia put in. ‘Emir Rashid, we are grateful for your presence here. We will ensure you are kept apprised of Echor’s movements as the campaign unfolds, and will take care of sending him false intelligence to draw him on to Shaliyah. We trust you will take full advantage.’

Rashid rose smoothly to his feet and bowed gracefully. ‘We will have victory, Ahm willing.’

Lucia rose also, and accepted a kiss on the hand from the emir. A flurry of insincere well-wishes from the men across the table propelled the Keshi nobleman from the room. Gurvon followed him, as he had facilitated the emir’s travel and participation.

‘Well, Magister Gyle,’ Rashid said once they were alone in the antechamber, ‘did that go as you wish?’

‘It did, Emir,’ he said, offering his hand.

Rashid studied it, then slowly took it. ‘Your Rondian hand-clasps are an odd gesture,’ he remarked. ‘Impersonal. It says much of your race. Cold lands, cold hearts.’

‘I don’t think our peoples are so different, Emir. Rulers rule, and the common herd bleat. In the end, the cream rises to the surface.’

Rashid’s eyebrows flickered. ‘I disagree. Your people are argumentative and sceptical. They question their betters too much. In that small room I saw mother overrule son, generals squabble with priests, and thieves like you – forgive me, but you are a thief, Gyle – dictate the future to an emperor. In my land, Ahm has anointed the kings and they speak with one voice. You are divided, and therefore flawed.’

‘Our divisions make us strong, Emir.’

‘Your gnosis makes you strong. All else underlines your godless weakness.’ Rashid patted his cheek amiably. ‘One day, Ahm will strike you all down with lightning from the skies and you will plunge into the fires of Shaitan. So it is written.’

Gurvon chuckled. ‘You believe that? I didn’t really see you as a fanatic, Emir.’

‘I am a pragmatic man, Magister Gyle, but I too do Ahm’s work.’ Rashid bowed. ‘We will not meet again as allies, Gurvon Gyle.’

‘A shame.’

Rashid raised an eyebrow. ‘Think you?’ He bowed again, and opened the door to the palace functionary waiting to guide him back to his windship. He would be gone within the hour.

*

Gurvon returned to the meeting room to find it quiet and gloomy, as if the departure of the colourful emir had drained the life from it. He saw Grand Prelate Wurther purse his lips as he returned; the clergyman had argued hard against entrapping Echor’s army in the coming crusade, claiming it was against the dictates of Kore to involve the heathen Keshi in their plans. He looked no happier to have met the enemy in the flesh. ‘Has he gone?’ he rumbled. He belched softly. ‘We would be better to take him to Headsman Square and end him right now. He will cause us grief, I warrant.’

‘The Keshi will rise in their millions when news of Echor’s defeat comes out,’ Dubrayle agreed. ‘It is a risk.’

‘It is no risk,’ Korion snapped. ‘Echor’s provincials are one thing; my legions are quite another. Let the Keshi rise – I will stamp them back down.’

Betillon snickered. ‘We know how to deal with uppity Noories.’

The room fell silent until Constant twitched and said, ‘I didn’t like that darkie. He dressed like a woman. Perhaps he is one?’

Gurvon watched the other men laugh at this tired old joke. He glanced at Lucia. You see what I have to put up with, her gaze seemed to say. You and I, we see them for what they are: children.

Aloud she said, ‘Time for the next matter: Treasurer Dubrayle, I believe the floor is yours.’

Gurvon glanced at Vult. This was the one part of the plan he hadn’t contributed to. It was something Dubrayle had cooked up with Vult – something to do with the slave trade. Lucia had demanded that the practice stop, not because she had any pity for Eastern slaves, but because she felt that dark skins were becoming too common in Yuros. She wanted a return to using Sydian and Vereloni slaves, who were at least Yuros-born.

The treasurer sat up, shuffled his papers and started, ‘My Lord Emperor, Mater-Imperia, gentlemen, may I introduce my own expert guests to this gathering?’ He looked at Lucia and after she gave her approval, Constant belatedly following suit, he rapped loudly on a side-door, which opened to reveal an old man in stained robes, bent as if he’d spent his best years hunched over illegible scrolls. He hobbled inside, followed by a man in plain tunic and short leggings, with a shaven skull and the Yothic character ‘Delta’ branded upon his forehead. His face was vacant, as if he were drugged or a simpleton. He carried a falcon on his wrist. The bird shrieked once, but was soothed into silence as he patted it – but it wasn’t that which made Gyle stare at ‘Delta’. It was his aura. All the magi in the room could see it: energies roiling and twisting strangely, like nothing they’d ever seen.

‘Exalted Ones,’ the old man said, ‘allow me to introduce myself. I am Ervyn Naxius, at your service.’

Gurvon knew of Naxius: he’d been the head of the Ordo Costruo based in Pontus, tending to Northpoint Tower and the northern reaches of the Bridge. Though people blamed Antonin Meiros for allowing the Crusades to cross the Leviathan Bridge, it was Ervyn Naxius and his followers who’d been bribed to cede Northpoint, in return for support for his own research into fields that Antonin Meiros had forbidden. Few knew the name now; Naxius and his adherents had vanished at the beginning of the First Crusade.

‘Welcome, Magister Naxius,’ Lucia said smoothly. ‘The empire has much to be grateful to you for.’

‘And you have repaid that gratitude many times over,’ Naxius purred. ‘The freedom to work unfettered has been priceless.’ He looked at the bald man and the hawk with the joyous ownership of a child with a new pet. ‘I have something truly wonderful to show you.’

He pulled a large crystal the size of his fist from a pocket. It was dead-looking, and not of any stone Gurvon knew. ‘Do you recognise it?’ he asked, and when everyone shook their heads, explained, ‘This is a “solarus”: a crystal we of the Ordo Costruo developed to give gnos’ tic strength to the Bridge. It takes in the rays of the sun, what we call “solar force”, and converts it to gnostic energy. A solarus can store more energy than any mere periapt.’

The magi around the table frowned. Each wore a periapt gem to enhance their gnosis. ‘Then why do we not all have one?’ Belonius Vult asked. ‘If this is an enhanced periapt, surely it should be made available to all worthies?’

‘Would that we could,’ sighed Naxius. ‘Sadly, the energy these sun-crystals radiate is so intense that it is debilitating. I am certain such eminent magi as yourselves are aware that the solarus crystals on the Bridge are deadly in prolonged doses – even a mage wearing protective wards can endure them for only a few minutes at a time. Once filled with solar force they cannot even be touched. We’ve tried using them as periapts, but unless they are sealed in lead they infect the user immediately with destructive humours that kill in months – and the lead destroys their effectiveness.’

‘Then what are they good for?’ Korion grumbled.

Naxius beamed. ‘Ah, what indeed? You will be amazed, great general: amazed! We have found a use for individual gems such as this that no mage could ever have predicted.’

‘So what is it?’ Betillon demanded impatiently.

The Ordo Costruo renegade held up a hand. ‘First, let me introduce my fellow demonstrator.’ He turned to the branded mage. ‘This is “Delta” – not perhaps the name he was born with’ – he indicated the man’s branded forehead – ‘but it is the obvious name for him now.’ He puffed up proudly. ‘He is a Souldrinker.’

The room was filled with gasps and scraping chair-legs as Betillon, Korion and Wurther jumped to their feet, aghast. Even Belonius Vult looked startled, and in truth, Gyle had barely managed to restrain himself from a similar horrified reaction. A Dokken in Pallas? Unthinkable!

The Ascension of Corineus had changed the world, for it had resulted in the creation of the magi – but there had been a number of acolytes of Corineus who had failed to become magi despite drinking the ambrosia. Instead, their gnosis was triggered afterwards by inhaling the soul of a dying mage and fed thereafter by the consumption of human souls. The reaction to this horrifying revelation was immediate and fatal: most had been hunted down without mercy. There weren’t many left now, but their deadly trait perpetuated through their descendants and they remained the magi’s most hated enemies – and their only real rivals.

‘Peace, be at peace!’ Naxius exclaimed as Korion, Betillon and Wurther’s gnostic energies flared.

He was echoed by Dubrayle, who cried, ‘Delta is no threat to you. He is a slave and his powers have been contained.’

The old mage cackled gleefully. ‘I’ve placed such bindings upon his mind that he can scarcely place one foot before the other without my permission.’

It was true that the Dokken’s eyes were chillingly empty. Gurvon glanced at Lucia, who was watching with calm equanimity. Clearly she had already been briefed and had no qualms at whatever Naxius was doing. He took his cue from her and sat back to watch.

Korion and Betillon belatedly looked at Lucia too, then slowly sat, but the Grand Prelate remained standing. ‘My lady, I must protest. The presence of an Amteh worshipper in this place was barely tolerable, but this is clear blasphemy.’

Lucia looked at the churchman disinterestedly. ‘You can always leave us, Grand Prelate. But this session will continue, with or without you.’

Wurther’s protests floundered. ‘My lady, I feel that I must remain, but under duress—’

‘Sit down, you old windbag,’ Betillon growled. ‘Your point’s made.’

‘Save your wibbling for Holy Day,’ Korion added scornfully.

Wurther glowered about him and settled ponderously back into his chair. It creaked in protest.

Naxius resumed his presentation, his voice childishly happy. ‘My lords, noble Lady, thank you for your attention. It is with great excitement that I will demonstrate this remarkable thing we have discovered.’ He clapped his fingers loudly and the door behind him opened wide enough for a soldier to shove a pale-skinned, skinny young man in torn and dirty clothes into the room. Naxius caught the boy’s shoulder with fingers like talons and held him immobile. ‘Let me introduce Orly: a thief, I’m sad to say.’ The mage displayed the youth’s left arm, which ended in a stump at the wrist. ‘Young Orly had his left hand removed for stealing two years ago. A few nights ago he was caught again and yesterday he was convicted. He will hang next week.’

The boy’s eyes were wide with terror as he fell to his knees. ‘Please, mercy,’ the young Pallacian started, but Naxius held up a hand to silence him.

‘Do not fear,’ the mage purred. ‘We are going to give you a reprieve – one you could never have dreamed of.’ He handed the inert solarus crystal to Delta.

The boy looked about the room. He clearly had no idea in whose presence he was, but he sobbed in gratitude, ‘Oh thank you, thank you, good sirs, madam, thankyouthankyou—’

His torrent of words ended as Naxius made a peremptory gesture and channelled kinetic gnosis. The young thief’s neck audibly snapped and he slumped to the floor, his face going from shock to bewilderment to betrayal before falling slack.

The falcon on Delta’s wrist shrieked as if marking the moment.

Gurvon stared, surprised to find himself mildly shocked, though Naxius’ reputation preceded him. Well, he’s got our attention …

Delta bent over and seemed to kiss the dead thief on the mouth. The watching men winced in distaste, but Gurvon also sensed curiosity; he doubted any of them had ever seen a Souldrinker in action. He certainly hadn’t.

The crystal in Delta’s hands lit faintly and Naxius’ voice took on a declamatory tone, as if he were lecturing to students.

‘Observe,’ he ordered. ‘Delta has now inhaled the soul of the young man, but he has not absorbed it himself. Instead, because of the presence of the solarus crystal and the gnostic inhibitions I have placed on Delta, Orly’s intellect is now preserved intact inside the crystal.’

Holy Kore! Gurvon looked at Vult, feeling his own eyes going wide.

‘And now!’ Naxius said theatrically, with a sweep of the arm.

Delta held up the crystal in front of the falcon on his wrist and it flared again. A stream of white light shafted from the gem into the eyes of the bird. It shrieked piteously, flapped its wings, half rose into the air and then fell from the man’s wrist and sprawled across the table. Everyone in the room except Lucia and Dubrayle recoiled from it.

‘What have you done?’ Korion demanded. ‘If there is danger to the emperor I will—’

‘Calm down, Kaltus,’ Lucia drawled. ‘You think I would risk my beloved only son?’

Naxius prodded the fallen falcon. ‘Get up, little bird,’ he cackled merrily.

The falcon stirred and then pulled itself upright and began to preen itself awkwardly. The watching magi stared.

Finally Vult broke the silence. ‘Did he just do what it appeared?’

Naxius giggled in delight. ‘Yes! You see it, don’t you? The soul of the thief Orly is now in the bird.’ He reached out a hand. ‘Orly,’ he said, addressing the falcon, ‘tap three times with your left leg.’

As they all watched, the falcon did precisely as instructed. ‘Now fly thrice around the room, then land on the chandelier.’

No one moved as the bird fulfilled these instructions exactly.

Naxius smirked. ‘We have found that the transplanted soul is extremely suggestible to command and rapidly falls into the habit of complete obedience.’

Calan Dubrayle, clearly Naxius’ sponsor, took up the narrative. ‘Imagine our cavalry, mounted on constructs that can follow precise instructions. Imagine winged venators with human intelligence. Imagine beasts of burden that need not be driven, just instructed where to deliver their loads. Imagine plough-horses that can work the fields alone. Imagine birds scouting miles ahead of the army and reporting back. Imagine rats and snakes able to slip beneath castle walls and attack the defenders. Imagine the unimaginable.’ He tapped the map of Dhassa and Kesh on the table. ‘All we need to make such miracles in the numbers we will need are animals, constructs – and thousands of human souls.’

Constant’s jaw worked but only little squeaks came out. Korion and Betillon were pale, their expressions torn between horror and greed. Wurther looked outraged. But Vult was fascinated, his fingers tapping rhythmically as no doubt a hundred more uses for such creatures ran through his mind.

Mater-Imperia Lucia looked as if she’d just gorged on chocolate.

And me? How do I feel? It’s very, very clever. And it’s probably the most horrifying thing I’ve ever seen.

‘Well,’ said Emperor Constant, ‘the Keshi are just beasts anyway. They shouldn’t mind a whit.’

Low laughter rippled about the room and Gurvon took care to join in, though he was staring at the face of the man called Delta. Now he could recognise something in those empty eyes: utter self-loathing and despair.

‘Have we done well?’ Naxius asked the throne.

Lucia smiled. ‘Magister Naxius, you have surpassed yourself.’

1

The Dawn to End All Night

The Rondians call it ‘The Dawn to End All Night’: the morning when the Blessed Three Hundred awoke and began to realise the gift they had been given. Imagine that sense of possibility, the sense of holding Urte in your hands! But it was a false dawn! They replaced Rimoni oppression with Rondian oppression! The true dawn of the Age of Light starts here, and now!

GENERAL LEROI ROBLER, ON THE EVE OF THE NOROS REVOLT, 909

Eastern Dhassa, on the continent of Antiopia

Zulhijja (Decore) 928

6th month of the Moontide

Vann Mercer was startled awake as his horses snorted and danced sideways. He hauled on the reins to pull them back into line, then cast about for what had startled them. He didn’t have to look far: a despatch rider was alongside his wagon, peering at him intently. ‘Vannaton Mercer?’ the man asked. His accent was clearly of Noros.

The man’s voice invoked home: snow-capped peaks, verdant forests and sudden storms, lush grass and tumbling rivers. It was so far from Vann’s present reality that for a moment his guts ached. The horizons were straight, the land here flat and brown. At least the temperature was bearable – Decore in the East was the onset of what passed for winter here; cold by local standards but akin to early spring in Noros.

‘Who’s asking?’

‘My name’s Relik Folsteyn, of Knebb. You won’t remember me, sir, but I was on the mountain, back in nine-ten. Part of Langstrit’s legion.’

Vann smiled sadly. The brotherhood of veterans. ‘Good to meet you, Folsteyn.’

‘Honoured, Cap.’ Folsteyn glanced at the wagon. ‘Fuckin’ hot place t’be selling wool bales, sir.’

‘It’s all I’ve got – but you’d be surprised, the weavers here snap them up.’ Vann took the proffered envelope. It looked official: the seal of the Norostein Watch was scuffed but unbroken. He recognised Jeris Muhren’s writing. It didn’t feel like good news.

‘Might I beg some water, Cap?’ Folsteyn asked. ‘It’s been a thirsty ride.’

Vann indicated the water tank on the side of his wagon. ‘Help yourself – I’ve plenty.’

‘Thank’ee,’ the rider said. He looked at Vann worriedly. ‘After you read that, we’ll be needing to talk.’

Vann was travelling with two dozen other traders; they’d all crossed the Bridge together once the military traffic had lessened. There was still trade to be had, mostly here in eastern Dhassa, away from the path of the Crusade. Vann’s family’s future was depending upon his success here, and his thoughts turned often to his wife Tesla and his son Alaron, waiting patiently at home in Norostein. He and Tesla had been estranged, but recent events had thrown them together again; despite everything, he still loved her. He still clung to the memory of the person she’d been. And his mage-son Alaron, naïve and impetuous but honest at heart, was the centre of his life.

He pulled his wagon to the side of the road, shouting to his fellow traders not to worry, that he’d catch them up. Then he looked down at the letter, filled with foreboding.

Perhaps if I never open it, nothing it contains will have happened …

He cursed the foolish notion and broke the seal. The letter was dated Junesse – six months ago. Even allowing for three months to traverse Verelon and Sydia on the coast road it had taken a long time to find him. But then, he’d always kept a low profile while travelling.

My dear friend Vann

I pray this reaches you promptly, and is the first word you receive of this matter. It is with utmost sadness that I must tell you that Tesla has passed away. She died 11th Junesse, of natural causes. Alaron is well and looking after your affairs in Norostein. He will write when he is able, but do not be concerned if you do not hear for some time. He sends his love, as do I. Take care on the road and avoid Imperial contact. May good fortune be with you, and may we meet again soon.

In haste

Jeris Muhren

written 12th Junesse, in Norostein

He read it again, carefully, then bowed his head. Tears threatened, but never quite came.

Tesla, my dearest, you would have gone to death with open arms.

When he looked up, Relik Folsteyn was watching him carefully. ‘Captain Muhren and your son left Norostein the same day the letter was written, Cap,’ he said, gruffly sympathetic.

‘What?’ Vann asked sharply. ‘Why?’

‘We don’t know, sir. But all along the Imperial Road from Brekaellen to Pontus, there’ve been Imperials looking for them – and you.’

A chill that overrode the sullen heat of the desert prickled his skin. ‘I wasn’t going to cross the Bridge this time, but when I got to Pontus I realised I had no chance of turning a profit unless I did my own trading.’ He swallowed. ‘Why are they looking for me?’

‘We don’t know, Cap. But it was Quizzies doing the asking.’

Inquisitors … Kore’s Blood. ‘Who sent you, Relik?’

‘The Merchants’ Guild – when they heard about the Inquisition, they decided to find you first. Jean Benoit sent us. His orders were that whoever found you should get you to safety.’

Benoit family had been disgraced for embezzlement and stripped of their titles and lands; the punishment had driven them into trading and young Jean Benoit, a pure-blood mage, had risen quickly, pulling many lower-blooded magi into his following as he swiftly rose to Guildmaster in Pallas. It was he, forty years ago, who had advised rich merchants to seek out and marry into impoverished mage families, and as a result Benoit’s influence was now immense. The Imperial magi took a different view; to them, Jean Benoit was kin to the Lord of Hel himself.

Vann licked his lips. Benoit was no friend to Noros or to provincial traders, though he had been instrumental in brokering the peace after the Noros Revolt. Civil wars were bad for trade, after all. The Pallas Merchants’ Guild had been bullying provincial traders for centuries; it had become worse under Benoit. ‘I don’t suppose I have much choice,’ he said wryly.

‘Not unless you enjoy chatting with Inquisitors,’ Folsteyn agreed.

‘Then I suppose I’m in your hands.’ He cast his eyes skywards and breathed a silent prayer for Tesla, his damaged and broken wife, finally at rest, and for Alaron, wherever on Urte he was.

Near the Isle of Glass, Javon coast, on the continent of Antiopia

Zulhijja (Decore) 928

6th month of the Moontide

Alaron dreamed of home and of his father, laughing and happy. Even his mother was joyous, her burns gone and her whole body restored to youth and beauty. He should have known from that alone that he was dreaming, but it seemed so real. Then a hand on his shoulder pulled him from sleep’s clutches and he jolted awake into a terrifying reality.

He was wrapped around a tiny girl with a hugely distended belly and skin the colour of dark coffee, and they were lying in the stern of a tiny skiff that was hovering above the ocean. The sun blazed through seaspray and the air was full of a watery roar.

‘The sea is rising again,’ the girl said, and he stared at her dumbly until his memory supplied her name: Ramita, Lord Meiros’ seventeen-year-old pregnant widow. They’d fled the attack on the Isle of Glass together, leaping into the skiff to escape Malevorn Andevarion, his old nemesis from college, and an unlikely bunch of shapechangers and Inquisitors. Then another memory emerged and he groped inside his jacket, sighing in relief as his hand fell on a long, hard scroll-case.

The Scytale of Corineus.

More mem

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...