- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

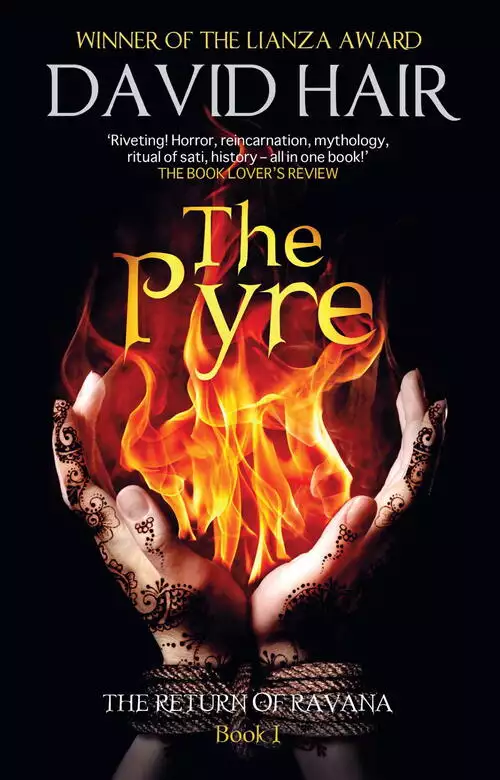

'David Hair hasn't just broken the mould. He's completely shattered it' - Bibliosanctum One deathless Demon King. Six ghostly queens. And only four twenty-first century young men and women to stand against a centuries-old evil . . . The first in award-winning author David Hair's series The Return of Ravana. Mandore, Rajasthan, 769 AD : the evil sorcerer-king, Ravindra-Raj, has devised a deadly ritual. He and his seven queens will burn on his funeral pyre, and he will rise again with the powers of Ravana, Demon-King of the epic Ramayana. But things go wrong when a court poet rescues the beautiful, spirited Queen Darya, ruining the ritual - and Ravindra's plans. Jodhpur, Rajasthan, 2010 : At the site of ancient Mandore, Vikram, Amanjit, Deepika and Rasita meet - and are forced to accept that this is not the first time they have come together to fight the deathless king. Now Ravindra and his ghostly brides are hunting them down. As vicious forces from the past come alive, Vikram needs to unlock truths that have been hidden for centuries, if they are to win this ancient battle . . . for the first and last time. 'Riveting ! Like its reincarnated heroes, I was drawn again and again to David Hair's gripping, blood-soaked tale' - Chris Bradford, author of Young Samurai

Release date: June 4, 2015

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Pyre

David Hair

The journal was right where he remembered putting it thirty years ago, buried two feet beneath the distinctive stone slab. It was wrapped in waterproof greased leather, in a painted wooden box that crumbled, rotten with age and damp, when he dug it out. To his considerable relief, it looked like the journal hadn’t been further damaged by its burial. The pages were cotton cloth at the front, then varying grades of paper that became more refined as he flicked through. The book smelled musty and the binding was frail. Some of the oldest pages, the cotton ones at the front, were more than a thousand years old, and it was to the first page, the earliest, that he went. The script was ancient, but he found he knew it, and silently translated the words as he traced them with a trembling finger, not quite daring to touch the page.

If you are reading this journal, then I hope you are me – you know what I mean.

I have come to believe that certain stories develop a life of their own. They are powerful because they are so widely known, so much a part of our culture – indeed, of our daily lives – that they become more than mere words.

Imagine, if you will, a tale that defines a people. It has heroes and villains, good and evil deeds; its very words are sacred to us. It is like a chess set, its pieces inhabited by the same souls, game after game. Or perhaps this tale is a living thing, a script that constantly seeks actors, and when it finds them, it inhabits those actors and possesses them utterly, finding new ways to express and re-express itself, time and time again.

What must it be like to be one of those souls, doomed to live the same life time and again, over and over, always acting out the tale, sometimes glorifying it, sometimes enhancing it, and always at great cost to themselves, for their whole existence is a prison sentence. Their fate is to live constantly as a plaything of an idea.

But you know what that’s like, don’t you?

Such a story is like a tyrannical god, inflicting itself upon unwilling worshippers.

I know this is real, because I am living such a tale, and I am doomed to live it over and over, for ever more – and by ‘I’, I mean ‘you’.

Over and over and yet again.

As he focused on the brief verse that followed, a thrill of unease – the same shivery feeling he always got when he saw those words – made the hairs on his arms stand up.

Time is water from the well of life

And I must draw that water with only my hands to bear it

My thin and fragile fingers cupped to receive it, every drop precious

But ere I have raised it to my lips, it has drained away

One day I will learn not to spill it and I will drink my fill

And finally be free

Aram Dhoop, Poet of Mandore

He blinked rapidly, remembering the last time he’d written those words, two years ago. He’d had to do a poem for English and though he’d had no idea then why, it had been one of the easiest assignments ever. The words had just flown from his pen, almost as if he were just copying out someone else’s work. And when his teacher had asked him what he was trying to say, he’d started, ‘It’s about reincarnation—’ and then stopped; he knew the poem did mean something important, but that was about as close as he could come to explaining it to someone else.

But that hadn’t mattered, apparently, because the teacher had entered his work in the inter-schools’ Poetry Cup competition that year – he’d been a little surprised how thrilled he’d felt when he’d got up in front of the whole school to accept the trophy from the headmaster.

And yet here were those very same words, set down in a strange – and yet not unfamiliar – hand on a page that pre-dated paper in a journal his forebears (if that was the right word) had been keeping for more than a thousand years.

He put the journal down. He would read it properly that night – though he knew already that the words would be as familiar as if he had written them yesterday.

There was one other thing hidden with the journal: a small leather pouch. It was empty. Strange; I almost expected the necklace to be inside this time. His hand still remembered the shape of the pendant: a pale crystal veined with burgundy streaks set into a tarnished decorative metal surround. He’d never forgotten the way it used to pulse queasily at his touch. Where the necklace was now, he had no idea.

The journal was unique, a scholar’s dream, but he had no intention of showing it to anyone. He had begun writing it many lifetimes and more than a thousand years ago, a record of his life that was centuries old; though the last time he had buried it was just thirty years ago.

And he himself was only seventeen years old.

Mandore, Rajasthan, AD 769

As the winter draws to an end and the heat rises again, the winds begin to blow across the Thar Desert: great clouds of dirty orange dust billowing out of the west. The men, if they must venture outside, go muffled in scarves, while the women throw the loose end of their dupattas over their heads, so that they look like colourful insects, swaying in the mirages. The arid land leaches away what little other colour there is; the pallid shrubs become coated in sand, the tiny mud houses and canvas tents are the same muted hues as the desert itself. The vibrant clothes of the people provide the only brightness, the colours feeding hearts and lifting spirits.

It has not rained for months, nor will it for many more – the only real rain comes once a year here, at the end of the summer, when for six to eight weeks the land is revitalised by sudden, brief torrential downpours so fierce that anyone caught outside finds themselves staggering under the onslaught even as they dance in relief that the monsoon has come at all. But this winter has been drier than usual and the old folk are whispering of worse to come. When the skies are orange with dust, it is always a bad year, they say.

This, the third year of the reign of Devaraja Pratihara, son of Nagabhata, certainly hasn’t been a good one for the town of Mandore. He moved his court, the heart of the Gujara-Pratihara Empire, to Avanti, leaving the old capital of Mandore in the hands of Ravindra-Raj, his third wife’s son. The desert folk whisper that the gods, displeased at this turn of events, have cursed Mandore; certainly the court and all its hangers-on have followed Devaraja to Avanti, leaving Mandore denuded and lost in dreams of its glorious royal past. Traders are few now, and houses that once thrived are abandoned, or taken over by squatters seeking shelter, or dismantled by stone-thieves looking for easy pickings. Some believe that Mandore’s curse is embodied in Ravindra-Raj himself – not that they would ever voice their fears out loud to strangers – for his cruelty and oppression are amongst the reasons so many have left. Those who lay the city’s current ills at Ravindra’s door claim once-proud Mandore is being strangled by the raja and his many offences against the gods.

*

Madan Shastri, the senapati, or commander, of the raja’s soldiers, watched Ravindra uneasily out of the corner of his eyes as he committed yet more such offences. Ravindra was not a man you ever looked at directly, not if you wanted to keep your eyes, as he was currently demonstrating.

‘Speak, Gautam! Speak!’ Ravindra roared as he pressed a white-hot iron to the naked prisoner’s chest. Once again the dungeon cell filled with the smell of seared flesh, causing even the most hardened of the watching courtiers to wince. Gautam screamed silently: his mouth moved, but no sounds emanated from him, for by now he was beyond speech. His whole body was so covered in welts and burns and cuts to make him unrecognisable to even his closest friends. Even if Ravindra were to show him mercy now, Gautam would never be the same. True mercy would be to slay him swiftly.

Shastri longed to end this, but one did not come between Ravindra and his pleasures. He looked away, only to be met by a sight almost as unpleasant – the smiling jowls of the raja’s favoured son, Prince Chetan.

‘Why Senapati Shastri, I do believe you look a little unwell,’ the prince drawled as he sipped a lemon sherbet. His expression kept changing as he was alternately bored and amused by the proceedings. ‘I’d have thought our noble captain would have the stomach for such unpleasant sights when it is in defence of my father and his realm.’ He lowered his voice and in a sly whisper he added, ‘Or is it fear of what Gautam might say that makes you look so very ill at ease?’

Shastri stiffened slightly. ‘Of course I have nothing to fear,’ he replied. ‘The conspiracy must be rooted out. All traitors must die.’

‘But you and Gautam were quite friendly, I thought?’ Prince Chetan’s eyes were sparkling with unfriendly mischief. The prince was a big man, larger even than his father, with heavy, slab-like muscles, and though he wasn’t a clever man, he was cunning, and in Ravindra’s court of whispers and cruelty that mattered more.

‘He was my superior. One must always cultivate amiable relations with those above us,’ Shastri replied uncomfortably.

Chetan grinned maliciously. ‘So your apparent amiable nature towards my father and me is just pretence, Senapati?’

Shastri frantically groped for the right words to lead him out of this dangerous little maze Chetan had woven, but he was saved from having to reply immediately when the door to the dungeon was flung open and Ravindra’s chief wife sashayed in. Rani Halika was wearing a vivid jewel-encrusted red sari and enough gold to ransom her husband.

She looked at Gautam’s shattered frame and tittered elegantly. ‘My lord, I trust he has not expired just yet? I wish to teach my sister-wives a lesson in loyalty.’ She looked about the dungeon, taking in the bloodstained floor, the nauseous courtiers and the grinning torturers lounging against the walls watching, and Chetan, her favourite son. She gave Shastri a voluptuous smile. ‘Senapati, how nice of you to join us. Are you well entertained?’

The raja turned to her. He was clad in armour inlaid with gold and silver and embossed with intricate tracing of hunting nobles and fleeing beasts. A speared tiger died eternally in the middle of his blood-speckled breastplate. His oiled moustaches and beard gleamed and his flushed cheeks were ruddy in the flickering torchlight. Though he had been here all night, destroying the body and mind of the latest man alleged to have conspired against him, he showed no trace of exhaustion. ‘Senapati Shastri has been our witness, my dear. Everyone trusts the good captain, so my brother’s confession will have greater credence if spoken in his presence.’

Shastri wondered if that truly was the only reason for his presence, for this was not normally something the raja insisted on when he tortured a man.

‘And do we have any interesting new names?’ the rani asked curiously.

Ravindra shrugged. ‘No one of note – a dozen of Gautam’s guards, a few scribes, a merchant or two – a disappointing conspiracy, doomed from the start to fail. How sad, that my own brother had so few real allies,’ he reflected with mock sorrow. He stroked his brother’s flayed chest. ‘Bring in the other wives, then, if you think it needful.’

‘My lord, no—!’ protested Shastri, but Ravindra cut him off with a chopping gesture.

Halika clapped her hands and a demure procession of six young women walked in, all except for one clad in bright saris of yellow and green and orange. The last girl wore a shapeless black robe that enveloped her entire form, leaving only a narrow slit for her eyes. Shastri watched her, feeling a distress that he couldn’t quite bring himself to understand. Darya was the raja’s latest bride, and the only foreign one. She’d been given to Ravindra by a Mohameddan from the western side of the desert. Something about her intense eyes and upright bearing always drew his attention.

He tore his gaze away and flashed a reassuring look at Padma, his little sister, the second youngest of Ravindra’s wives. It was supposed to be an honour, to be chosen by the raja, but he knew Padma dwelt in misery. Her girlish prettiness had already faded and she didn’t look healthy. She looked back at him dazedly and then dropped her gaze, almost as if she were frightened to meet his eye.

His nerves tightened.

All the girls recoiled when they saw the bloody form hanging from the chains in the centre of the room, but Rani Halika clapped her hands and crowed, ‘See what we have here, girls!’ She gestured at the broken man. ‘A failed plotter! Do you even know who it is?’ She peered at the vacant-faced girl nearest her. ‘Do you know who it is, Meena?’

Meena shook her head, her face frightened. Two of the ranis involuntarily backed away, pretty Rakhi going pale and rake-thin Jyoti vomiting against the wall. Even hollow-eyed Aruna looked frightened, despite the clear signs of opium intoxication in her glazed eyes.

‘Why, Meena, do you not recognise your own dear brother-in-law? Surely you know Prince Gautam? It appears that Gautam thought he could turn the guards against our lord and master. But of course our guards are totally loyal, aren’t they, my beloved husband?’ Halika stroked Ravindra’s mailed arm.

The young queens all shuddered, unable to tear their eyes from the bloodied mess that was all that remained of proud Prince Gautam. Shastri watched them all as they stood trembling – except Rani Darya. Through the narrow eye-slit he momentarily met a composed gaze, then as she became aware of his regard, she too started shaking, and for a moment it crossed his mind that she was just mimicking the others.

Surely not. Of course she must be as upset as the rest of them . . .

He wondered what she looked like under that thick black robe – a burkha – was she beautiful? His sister Padma spoke well enough of her, but said that she seldom interacted with the other wives. Was she intelligent and gentle? Were there hidden reserves? Her eyes were the most enchanting green he had ever seen, the few glimpses he’d had of her face revealed features that were angular and pleasing, and her hands were long and elegant. But only Ravindra had the privilege of seeing what lay beneath that heavy robe.

He caught the girl returning his stare and flicked his eyes away – straight into Ravindra’s predatory gaze. He flattened his expression, dreading what the raja might have read in his face, but his ruler merely smiled knowingly before returning his gaze to his brother.

‘I think Gautam’s told us all he knows,’ he said sadly. ‘Bring in that poet fellow and let him say a few words. Then we’ll release my poor brother from his torment.’

Shastri looked carefully at the floor and prayed that Gautam could hold out until he was ‘released’.

*

Aram Dhoop, the Court Poet, was dozing, huddled uncomfortably against the wall outside the dungeon, where he had been for the last ten hours. At first the cries of the tortured prince had made sleep impossible, but it was amazing what one could endure if one tried. His reverie was shattered by a rough hand on his shoulder shaking him awake: one of the dungeon guards, a hard-faced man with a world-weary manner. Aram quite liked Pranav, except when the gaoler was hurting people for his lord, when he became a different person entirely. ‘I do what I must, or I face the consequences,’ Pranav had explained quietly once, after Aram had wondered aloud how he slept at night.

‘But then, who am I to judge?’ he acknowledged quietly to himself. ‘I’ve slept most of the night in earshot of the one good man in this kingdom being eviscerated.’ He straightened as the guard gestured, indicating that he was wanted inside; Pranav’s expression gave nothing away. Aram hurried inside, hoping that all they wanted was his poetic abilities.

It appeared that was indeed the case, so the Court Poet murmured a few words of consolation over the tortured form of the only decent man in the fortress before blessing him in the name of the gods. Aram wasn’t a priest, but the last of the holy men had fled months ago when it became apparent just what sort of a man Ravindra-Raj was. Many of the soldiers had deserted as well, but Ravindra had bribed, charmed or terrified enough men to maintain control. There was something unsettling about him, something of the cobra in his hooded eyes. Just being close to him was enough to paralyse thought.

As he finished his blessing, Aram glanced along the line of wives. While he counted every man here a beast, he felt sorry for these delicate creatures – except for Halika, of course, who was every bit as bad as Ravindra. At least I need only recite poetry to the raja, he reflected as he ran his eye down the line. These poor creatures must bear his children. Only the long-term wives, Halika, Meena and Rakhi, had given Ravindra male heirs thus far; Jyoti and Aruna had produced daughters. And only Chetan had so far survived to adulthood, but there were more in the nurseries. Imagining how intimate these women had to be with their lord and husband was nauseating.

Empathy was a curse, here in dying Mandore.

His eyes flickered nervously past Padma, Senapati Shastri’s little sister. He feared she was beginning to take a dangerous liking to him. She asked for him to sing too often, watched him too avidly. The raja had executed men for less. But even as he reminded himself of this, he could not help his own gaze drifting to the black-clad girl at the end of the line and feeling a now-familiar twinge of longing.

Apart from the eunuchs and the raja himself, he was the only man allowed to see her face uncovered, when called to the zenana to play for the entertainment of the women. Darya’s face had melted his heart the moment he had seen her reclining beside a pond in the women’s quarters. Loneliness, loss, the courage to endure, all had been captured in her expression. She was like a hawk, tethered but not tamed; a poem far beyond his skills to write. In his most secret dreams he worshipped her.

Rani Halika clapped her hands a third time. ‘Now, girls, the lesson for the day is this: there is but one god and his name is Ravindra-Raj. He rules every part of this world that you will ever know. He owns your body, and he owns your soul, and you owe him everything – in life and in death. May you be as thankful as you ought, for you see what befalls those who conspire against him.’ She knelt, prostrating herself before the raja, and Ravindra smiled coldly as the other women followed suit, a line of genuflecting gaudy birds with wide-eyed, terrified faces . . . except for one. Darya lifted her head haughtily, turned her back and stomped away.

Halika looked outraged, but before she could say a word, Ravindra smiled and commanded, ‘Send her to me tonight.’

The chief wife looked displeased. ‘My lord—’

But her protest died on her lips when Ravindra looked at her sternly. She bowed her head and stayed silent.

Ravindra turned back to his younger brother and stroked his swollen purple cheek. ‘Now, dear brother, I think your lesson is learned. Shall I release you?’

The prisoner quivered, and Aram realised to his horror that Gautam was still aware.

With a soft, almost sensuous sigh, Ravindra rammed the poker through Gautam’s chest and into his heart. There was a great crack and a tearing sound and the prince’s blood came spurting, sizzling, from the wound and coated the raja. A stench of roasting meat overwhelmed the chamber. Then in a grotesque parody of remorse, Ravindra closed his eyes and hugged his dying brother.

*

Aram Dhoop closed his eyes and sang. His voice floated through the walled garden to the carved red sandstone latticework that hid the faces of the queens. Somewhere up there, Darya would be sitting alone, he was sure, shunned by the other wives as a Mohameddan; lonely, lost, yearning for a gentle touch: his touch. He knew this with complete certainty. He sang of love and hope. He sang for her.

What is she thinking as she sits up there, staring through the grille at me? Does she know these songs are for her?

Aram Dhoop had been born here in Mandore. It was always clear he was going to be too small to be a warrior, but his father had ensured he was educated. Not only could he read and write, but he had become a fine musician. He’d hoped to be taken to Avanti when Devaraja Pratihara shifted his court, but the raja had an enormous entourage and many poets and musicians, and he’d been overlooked. It hadn’t been for any lack of talent, but his high-birthed fellow poets – as vicious a flock of songbirds as ever pecked down a rival – had never accepted him as one of their clique, ostracising him and ensuring he never had the chance to catch the ear of the maharaja. Now, left behind in the obscurity of Mandore, he lived on his nerves in the cruel, deadly court of Ravindra-Raj, where a slip of the tongue could be as fatal as a sip of poison.

Would that I could ride free like one of those lumbering warriors! How unfair is a world that allows talentless brutes to prosper while the artistic must live hand-to-mouth . . .

His dream extended, as it was wont to do, to include a beautiful Persian girl at his side, laughing at his wit, weeping at the beauty of his voice and gazing at him in adoration as the priests made them one.

Does she feel as I do? Does she yearn for me as I yearn for her? Does her heart swell as my voice swells? Does it beat in time to the rhythm of my song?

But no matter how passionately he sang, or how prettily he played, the red sandstone latticework walls of the zenana gave him no sign that he was heard at all.

*

Senapati Madan Shastri stood stolidly as Rani Halika wafted towards him across the rosewater-perfumed room. He felt awkward standing there on the threshold of the women’s quarters, but Halika herself had commanded his presence.

‘Ah, Senapati, thank you for coming. Have you brought the eunuch?’

He nodded wordlessly and gestured to the pasty-faced man. He found the practice of castrating servants revolting, but the court had many such creatures now that Ravindra reigned. Still, at least the eunuch’s presence meant that he wasn’t alone with Rani Halika. That carried far too many dangers, for all that her worldly sensuality repulsed him. He turned away, anxious to be gone.

But the head wife had not yet finished playing with him. ‘Stay, Shastri, please. The other girls are skittish tonight; they may need to be restrained while we sedate them. Don’t worry, your sister is no problem. Padma is such a compliant girl.’ She made this observation sound both complimentary and sneering.

Before Shastri could respond, the eunuch, Uday, simpered, ‘I have brought an extra-strong dose for her, mistress.’

The fluting sound of Uday’s voice was enough to make Shastri wince, but Halika was pleased. ‘Good, good. Come with me.’

Shastri could scarcely hide his disgust at this task, but Uday’s expression was well schooled. He’s better than me at this, Shastri thought, as he followed the queen and the eunuch to the first of the bedrooms – scarcely larger than a prison cell – where the queens slept.

Halika was the eldest queen, a courtesan Ravindra had chosen as his bride when he was just another strutting nobleman of the Pratihara court, albeit more vicious and skilled than most. Their union had been the start of his ascent. Halika was in her early forties now, and still a striking woman, despite bearing three children to her lord.

Halika might be a bride chosen as a kindred soul, but Ravindra’s later wives were all chosen for social advantage. Meena, a plump and stupid woman now in her thirties, had brought with her a huge dowry. Rakhi was a prize of tribal warfare; first choice of the spoils following Ravindra’s victory on the battlefield. Jyoti, the only daughter of a high priest, brought great kudos, while Aruna, as the daughter of a man infamous for his ability to source opium from the north, brought great power. And Padma had secured the alliance with Shastri’s family at a time when that had meant something. Shastri’s father had approved the union in his dotage, something the senapati had never forgiven, even at his father’s grave-side.

Only Darya, the Persian girl, did not fit this pattern. No one knew what had driven Ravindra to pursue her, but there was endless speculation.

The first five wives all took their ‘medicine’ calmly – and in Aruna’s case, eagerly, which filled Shastri with pity as he watched them succumb to the poppy-milk. Clearly the debilitating dream-life of the addict was preferable to the reality of life in the claws of Ravindra and Halika. Padma was already snoring as he left her and he sighed, remembering with sadness the lively intelligence that had once shone in her eyes.

It was the newest rani who was resisting, which was no surprise. Darya spat at them when her cell was opened, snarling and shrieking like a wildcat. When Halika commanded Shastri to restrain her, she bundled herself in her burkha, hiding her face.

‘Must s. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...