- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

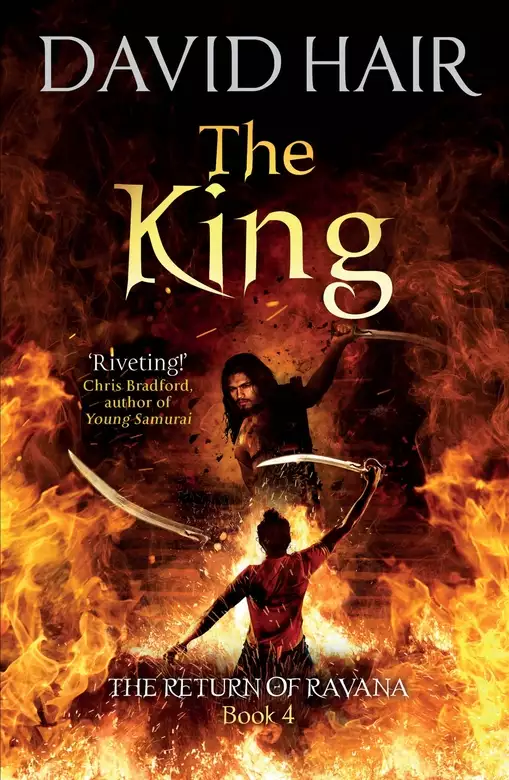

There is no escape from destiny . . . is there? 'Riveting! Like its reincarnated heroes, I was drawn again and again to David Hair's gripping, blood-soaked tale' - Chris Bradford, author of Young Samurai For four young men and women trapped in its story-cycle, the Ramayana is not just a legend: it is their fate! In every life they have ever lived, Vikram, Amanjit, Rasita and Deepika have been persecuted and killed by Ravindra on his quest to reincarnate as Ravana, the Demon-King. Now Ravindra has captured Rasita, and demonic beings are rallying to his cause. His triumph is looking certain. Vikram and Amanjit must rescue Rasita - but in every past life, Vikram has died at Ravindra's hands. This time, failure is not an option. This time, if Ravindra wins, it will be for ever. 'David Hair hasn't just broken the mould. He's completely shattered it' - Bibliosanctum Ages-old mysteries must be uncovered and forgotten powers regained as the fight to defeat Ravindra moves toward the final, heart-stopping climax and a finalé that is as startling as it is electrifying.

Release date: January 10, 2019

Publisher: Jo Fletcher Books

Print pages: 295

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The King

David Hair

The Photographer

Harappa, Punjab, April 1947

‘Mister Tim – Tim-sahib! Chai? Chai?’

The shrill cry jolted the white man beneath the straw hat from his daydream. He looked down from his vantage point, a stone platform at the highest point of the excavations, and waved to the little chai-wallah below. Sweat had plastered his shirt to his back and standing up for too long in this heat was dizzying. The grit filling the air had itched its way into the corners of his eyes and dried the roof of his mouth. It was only April – what would the height of summer be like here? Realising that he was really thirsty, he waved again and called, ‘Yes, please, Ramesh. Make it a big one. I’ll come down!’

‘No–no, Tim-sahib, I climb! I climb!’ The little urchin – he was no more than eleven – swarmed up the rocks like one of the brown monkeys that infested the site, grinning through uneven white teeth. ‘See? I climb.’ The boy’s limited English was definitely improving. In seconds he was crouched beside the Englishman in the shade of the pinnacle and peering around, delighted to be so high up. ‘Like ants,’ he grinned, pointing down at the dozens of men labouring below.

Tim Southby smiled back. ‘Just like ants,’ he agreed.

The boy poured a cup of sweet, spicy tea, and handed it to the Englishman with hero worship in his eyes. To them he was a war hero, a fighter pilot who’d won the DFC and Bar at the Battle of Britain. Those surreal, harrowing days had ended when an ME-109 got him in its sights and blasted his right leg off below the knee, so now he was just a photographer with a wooden leg. But everyone here insisted on treating him like some kind of minor deity. It wasn’t something he enjoyed.

History and photography had been his twin passions growing up, and when the war was over he’d needed little persuasion to leave battered, miserable England behind to join an old school chum here in the Punjab, especially after his sweetheart Annie had made it abundantly clear that a one-legged man – even a hero – could offer her nothing. Within weeks of dumping him, unable to bear his ‘repulsive scars’, she’d latched on to one of his squadron mates, so when his ship left Southampton, he’d been on the foredeck looking determinedly ahead.

Ramesh drew his attention back, fishing into a pocket and pulling out a little metal disc. ‘Money,’ he said, in an awed voice. ‘Old people money.’ He showed it to Southby, who took it thoughtfully.

‘Look,’ he said, showing the boy the etched figure of a seated man in profile. ‘It’s another one showing a king.’

‘King?’ The boy tried out the word.

‘Your word is “Raja”,’ Southby told him, returning the coin – they were common enough here that he could turn a blind eye to it disappearing back into a grubby pocket instead of being handed over to the site supervisor. Together, they sipped the chai and gazed over the dig, which extended hundreds of yards in every direction. All around them were trenches and walkways bridging holes and walls as the shape of the buried city slowly emerged from the earth like dinosaur bones.

‘This place may be the most significant archaeological dig of the era,’ Southby said, more to himself than the boy, who wouldn’t understand most of what he was saying. ‘Hammond believes these Indus Valley sites may predate Egypt or Sumeria: this may be the very place where man first evolved civilisation. There are drains and watercourses, walls, streets . . . it’s magnificent. All the stone blocks are regular, precisely placed and fitted. And there is no obvious royal or religious ostentation, either – the society here must have been far more egalitarian than later cultures. Before the warlords and priests got their grip on the people,’ he added vehemently, thinking of generals and priests he’d known in the war, men who thought only in terms of ‘acceptable attrition’ and ‘sacrifice for the greater good’.

‘This place must have been a relative paradise, an island of culture in a sea of primitive barbarism.’

‘Baa-baa . . .’ Ramesh echoed, giggling at the word.

‘Bar-bar-ism.’ Southby grinned. ‘Actually, the word does come from “baa-baa” – the noise the Romans heard when the Germanic tribes spoke.’ He grunted. ‘Damned Germans, still causing trouble.’ He finished his tea and was about to rise when a movement below caught his eye. ‘Hey, who’s your friend?’

‘Friend?’ Ramesh puzzled over the word as he peered into the shadows. ‘Oh, it’s Kamila – Kamila!’ He waved a hand and a plump girl of about his age slunk from behind a rock and stared up at them.

‘Hello!’ Southby called down.

The girl shrank back. Ramesh called to her in his rapid-fire Punjabi and she answered tentatively. ‘Kamila is scared of you,’ Ramesh reported.

‘I won’t bite her.’

‘Bite!’ Ramesh chortled, snapping his teeth. ‘Bite-bite-bite!’ He called something teasing to the girl in his own tongue, and she took fright and fled. ‘Heh-heh. I say to her, “Sahib will bite you!”’

‘For shame, Ramesh. She’ll be scared of me for the rest of her life, now.’

The boy grinned mischievously until an impatient voice shouted in Punjabi. Ramesh shouted back, reclaimed Southby’s empty cup and with a wave, he was gone, bouncing back down the pile of stones.

Ramesh was soon replaced by the foreman, Anand Gupta, a plump fellow who always smelled like he needed a bath. His moustaches were always immaculate, though. ‘Good evening, Southby-sahib,’ he greeted the Englishman. ‘Is it a good day for pictures? Is the light good today?’ he asked politely, although he had little knowledge of the arcane arts of photography.

Southby shook his head. ‘The air is very hazy today, Anand. Not good for photography, only for pretty sunsets. There’s a lot of smoke coming from the cities. More even than during the winter.’ He thought about that. ‘Is there trouble there, Anand?’

Anand Gupta frowned. ‘There is always trouble these days, Southby-sahib. Ever since Jinnah won the right for this new “Pakistan”, this Muslim state. My people are worried. They say Muslims are killing Sikhs and Hindus here in Western Punjab, and Sikhs and Hindus are killing Muslims in Hindustan. It is not good.’

‘It isn’t good,’ Southby agreed, scanning the hazy horizons. Most of the early workers had come from the nearby town of Harappa – well, it was little more than a village, really – until the need for labour had increased; now it was a pretty mixed crew, from all over the region. There had already been trouble between the Muslims and Hindus, fuelled by the rumours. But Southby was just the camera-jockey. The workers were Gupta and Hammond’s problem.

‘They say the Muslim National Guard are going from village to village,’ Gupta added. ‘The Guard have been declared illegal, but the army does nothing – you Britishers, you do nothing,’ he added sullenly.

Southby said apologetically, ‘Welcome to independence. You have to solve your own problems when you’re independent.’

‘You British caused most of those problems,’ Gupta snapped back, then bit his tongue. ‘I am sorry, Southby-sahib. I know it is not your fault personally. I am talking from worry only.’ He hung his head. ‘I am talking too much.’

Southby inclined his head sympathetically. Gupta wasn’t a bad old stick, and he must be worried for his family and himself, a Hindu stuck here in what would soon be the territory of Pakistan.

‘We have been given guarantees from those men who will form the new administration in Islamabad,’ he reminded the foreman. ‘You and your people will be safe here.’

Gupta looked at him with troubled eyes. ‘I am thinking you are very naïve, Southby-sahib.’

*

Southby woke to find a gun jammed viciously into his cheek. The man wielding it looked like an Afghani tribesman, but he wore a deep green overcoat and the crescent badge of the outlawed Muslim National Guard. His lean, scarred face was buried in a spade-like beard; his eyes were sunken pits. The skin on his hands and face was blotched and pitted all over, as if he’d been scalded by boiling water as a child.

‘Get up, English,’ the man snarled, poking him with the gun muzzle, and now Southby could see two smaller men behind him, dressed in the same uniform, with rifles levelled at him.

Southby slowly lifted his hands. He was unsurprised to find himself calm; any fear of death had been burned away in the skies above England, exorcised by the sounds of shredding fuselage and the pumping guns of the Messerschmitt. ‘What is going on here?’ he asked levelly.

‘You are leaving, English,’ the big man told him. ‘This is not your land any more. Get dressed, gather your belongings.’

‘Where’s Hammond?’ Southby demanded. One of the men behind his captor snarled and snapped something. The scarred man barked back, and the other man subsided.

‘Mister Hammond is being packed away also. Now get up, Mister Southby, before I ask my friends here to help you.’

The two riflemen grinned wolfishly at him, stroking their weapons.

After the humiliation of having to strap on his artificial lower leg under the sneering eyes of these men, Southby quickly gathered his gear before working up the nerve to ask the scar-faced spokesman, ‘Who are you?’ He wasn’t really expecting a reply.

‘My name is Mehtan Ali,’ the man replied. ‘I am a commander of the Guard.’ He was leafing through the photographs with surprising interest. ‘These are fascinating, are they not?’ He examined a shot Southby had taken of Mohenjo-Daro to the south, for comparison purposes to this site. ‘These sites are all from the same period?’

‘We think so,’ Southby responded coolly, jamming his clothes into his battered suitcase. ‘Are you a scholar, Mehtan Ali?’

‘I have been many things,’ Mehtan replied. ‘What are you Britishers calling these places?’

‘Harappan, named for this site,’ Southby replied. ‘Look, we have permits and—’

‘Your permits mean nothing, Mister Southby. I am moving you for your own protection.’ Mehtan Ali opened a drawer before Southby could reach it and removed Southby’s revolver. ‘I do not think you will be needing this,’ he said mildly, thrusting the gun into his own belt. ‘My soldiers would take it amiss if they saw it.’

‘What about the workers here?’ Southby asked, failing to keep anxiety from his voice.

Mehtan Ali scowled and the thin veneer of civility vanished. ‘This is Pakistan now, Mister Southby: an Islamic state.’

‘Not until June.’

‘It has always been Muslim, Mister Southby – even before the Ghori crushed that pig Prithviraj Chauhan, this region bowed to Allah. But it needs to be purified anew.’ He looked at Southby’s suitcase and the bags containing his photographic equipment. ‘Is that all? Then come.’

Southby hefted his gear and walked outside. Dawn had not yet broken, but in the dim light he could see fierce green-clad irregulars everywhere, all of them brandishing rifles and vicious-looking knives. He could see Gupta, standing amongst a huddled group of workmen; with a chill he realised they were all Hindu. The Muslim workers appeared to be walking freely among the fighting men, although they too looked frightened.

Southby turned back to Mehtan Ali. ‘Now, see here—’ he began, but his words were choked off when Mehtan casually grabbed his throat in a vice-like grip.

‘You will be silent, Mister Southby.’ He released his hold, leaving Southby doubled over, fighting for breath, his neck throbbing.

Southby’s cases were taken and loaded onto a Jeep, but he himself was led to a vantage point overlooking the dig. Hammond was there too, his cheek bleeding and his eye puffing up.

‘Southby!’ the archaeologist exclaimed. ‘Thank God – are you all right?’

‘I’m—’

But Southby’s intended words were silenced by a sudden volley of gunfire. He spun round, looking for the Hindu workmen, but they had already been reduced to a bloody tangle of bodies. Riflemen poked through the fallen, laughing and calling to each other as they bayoneted anyone unfortunate enough to still be breathing.

He turned to Mehtan Ali. ‘By all that’s decent, man, what are you doing? That’s barbaric!’

The Muslim captain’s face held little expression in the half-light. He ignored Southby’s tirade completely. ‘Harappa. Mohenjo-Daro. I have always been drawn to these places. We knew they were there, long before you British “discovered” them. Sometimes I feel that they call to me . . .’

‘The workers . . . your men have . . .’ Hammond stared, wide-eyed.

Mehtan Ali’s eyes remained unfocused, as if he were looking into the past. ‘This was the cradle of civilisation,’ he said softly, ‘a great Bronze Age civilisation, the equal of anything in your Iliads and Odysseys. This was a place of legend.’ He turned to them slowly, his voice reverent. ‘This is the birthplace of India. Imagine that.’

Hammond looked fearfully at Southby. Do not provoke him, Southby tried to convey with his eyes; he’s clearly dangerously insane. Southby turned away – and saw something else that sucked away his breath.

Two bodies were swinging from a gallows made of tent poles: Ramesh and his friend Kamila had been hanged, then spitted through the belly with spears. The corpses swung slowly in the dawn breeze. Their eyes were open, their mouths frozen in soundless screams.

Mehtan Ali followed his gaze. ‘Ah, yes,’ he said, with immense satisfaction. ‘It is a momentous day. A day of great victories.’

CHAPTER ONE

A Secret Wedding, and After

Pushkar, Rajasthan, March 2011

Amanjit Singh Bajaj rode a white horse, wearing a heavy white sherwani and a red turban. He carried a gold-hilted scimitar. About him, a small group of family and friends danced and sang with the band, a loose gaggle of trumpeters, cymbal-bangers, drummers and fire-eaters, as they clamoured through the streets of Pushkar. Before them was the final climb to the Brahma temple, where his beloved awaited him. They had a Sikh giani and a Hindu pandit, for this ceremony was going to be a weird blend of Sikh and Hindu traditions – one to make the traditionalists wince, not that he cared. He grinned down at his mother Kiran, clad in her widow’s garb, looking torn between tears and happiness. He smirked at his brother Bishin, who was dancing with an impossibly lovely local girl in a pale yellow sari. He tossed money to the musicians to keep them playing hard, all the while laughing for such joy that he could almost ignore the strangeness of it all.

For this wasn’t Pushkar at all – not the real Pushkar, anyway. This was a secret Pushkar, a Pushkar few could find – but he and Vikram Khandavani, his soul-brother, could. Vikram was his stepbrother too, son of his mother’s dead husband. Vikram was flanking the procession; it was he who’d brought the families from real Pushkar to this other place so they could bear witness as Amanjit married his beloved Deepika. They’d told the guests it was an exclusive theme park, for in this hidden Pushkar, the town was still mediaeval, with no electricity, no cars, no reception for their mobiles. There were horses on the streets, and far fewer people. If they’d looked closely enough, they might even have been able to discern that the moon was not a lump of inert rock orbiting the Earth, but a silver chariot driven by a god. This Pushkar was truly legendary: one of those rare spots where belief had generated a different place right around the corner from reality.

So far, none of his family had noticed the lack of power lines or vehicles in the streets, or the out-of-time locals; they were admiring the costumes, pointing at the armoured swordsmen on the streets and laughingly keeping an eye out for demons – all just part of the entertainment, something to marvel at while drinking and partying. Very Punjabi, he thought, smiling.

He looked over at Vikram, who was shadowing the procession, holding a bow and poised for action. Vikram was no longer the skinny, short-sighted young man he’d first met. He’d never be tall, but he was all toned, lean muscle. His hair had grown and was now caught back in a ponytail. He had an erect bearing and an air of grace and command about him; his eyes, filled with knowledge and old sorrow, made him look older than his years. In a way, he was: Vikram could remember all his past lives, and perform feats far beyond normal men. He was Amanjit’s closest friend, and when he married Amanjit’s sister Rasita, they would truly be brothers.

His smile faltered when he thought of Ras. Where is she? Is she safe?

It was hard to ignore such burning questions, but he was resolved to, for Deepika’s sake. With a prayer, he pushed Ras’ image to the back of his mind; this wasn’t the day to dwell on such things. He waved at Vikram, then nudged his horse around the final bend and looked up, seeking his bride.

There she was! At the top of the stairs Deepika waited for him, shining like an angel in the midst of bewildered-looking girlfriends, cousins and parents. She was wrapped in a scarlet wedding sari stiff with embroidery and decoration and glittering with gems and sequins. Her lovely face peered out from between the folds of the pallu. When she met his eyes, his heart sped.

Today, finally, they were going to marry.

He looked back at Vikram, who gave a taut smile. Be happy, Amanjit-bhai, his eyes said, then he looked away and Amanjit guessed he was thinking of Rasita too.

We’ll get her back, brother. Have faith.

Then his eyes went forward again, and all he could think of was how his heart might burst before he was married, it was hammering so hard.

*

A week after the wedding found Vikram in the courtyard of the Brahma temple, bare-chested, going through a sword drill . . . again. Apart from an ancient man in orange robes with dreadlocks past his knees, he was alone. Somewhere in the raja’s palace, Amanjit and Deepika were also alone, but together, laughing, joking, holding hands – being in love. Being married. They were two halves of a whole and it was beautiful to see, even if that was denied him, for now at least.

Memories of the wedding flooded back: the love, the laughter, the singing, the music, the dancing – all night, like dervishes! Even he had been able to put all his fears aside for a while.

‘Focus, Chand,’ Sage Vishwamitra warned again. He had called Vikram ‘Chand’ over many lifetimes; he was too old to change now, he said.

Vikram stopped and refocused, centring his balance and flexing. ‘Sorry, Guru-ji.’

‘A poorly executed drill cheats only yourself,’ Vishwamitra told him for the third time that morning. ‘Again – and perfect, this time, please.’

This time Vikram threw himself into the routine, sending the blade flashing about him, each movement graceful and as good as it could be. He wasn’t as blindingly fast or powerful as Amanjit, but he was still pretty damn good, and by the time he’d finished, he was breathing hard and sweating.

He gulped down some water, then sat with the sage and gazed out through the gates towards the lake. Sunshine glittered distantly on water. In the real world, an inept de-silting operation had left the lake all but dried up, but in this legend-place it was full – it still had fish and even crocodiles in it. Vikram had been told that in the real world, worshippers long ago used to allow themselves to be eaten by the crocodiles – it was said to be good luck, although presumably in their next life!

Good luck for the crocodile, anyway . . .

After the wedding, Vikram had taken the guests, who all believed they had been in some beautiful mediaeval theme park near Pushkar, back to the real world. This was the last day of Amanjit and Deepika’s brief honeymoon; tomorrow they too would resume training – they couldn’t afford to set aside any more time for pleasure, not with so much at stake. The wedding had been important and necessary, but now it was time to refocus on an ages-old conflict that appeared to be coming to a head.

‘Have you formulated a plan?’ Vishwamitra asked.

‘Tentatively, Guru-ji,’ Vikram replied, ‘but I haven’t talked it through with Amanjit and Dee yet, so nothing is set in stone.’ He ticked off the points on his fingers as he explained. ‘So, here’s the basic idea: we’re guessing Ravindra has taken Rasita to “Lanka”, which we presume is actually “Sri Lanka”, as the Ramayana tells. When Ravindra set up the ritual in Mandore, he needed to kill each of the queens while they were wearing their heart-stones, and that went wrong when Padma, who’s now Ras, gave her brother Shastri, or Amanjit, her heart-stone to give to me, and I – as Aram Dhoop, obviously – rescued Dee, or Darya, as she was. So he doesn’t have everything he needs. He’s got Ras, but not her heart-stone. He has Deepika’s heart-stone, but not Dee – and he thinks she’s dead. And he seems to need to kill me, which he hasn’t done either.’ His face clouded. ‘Yet.’

The sage put a hand on his arm. ‘In the Ramayana, Ravana tries to seduce Sita; he does not use violence against her. So she should be physically safe, and I am quite sure you can count on her loyalty. She will not be seduced. You know that.’

Vikram didn’t feel so sure; his past lives had told him that flesh and will could sometimes be weak, even in the strongest person. ‘In the Ramayana, yes – but we don’t know why a lot of what we do appears to be mirroring the Ramayana, or why sometimes it doesn’t. Like Deepika and what happened to her: she transforms into the Goddess Kali when she loses her temper – but Kali isn’t part of the Ramayana, is she? So even now, we don’t know the rules! We don’t know anything for sure. How do we know that in this life, Ravindra has to seduce her at all? Maybe he’ll just kill her? Or rape her? He might have already . . . and we’ve done nothing.’ He hung his head, distraught at his helplessness.

Vishwamitra put a hand on his shoulder. ‘Chand, this delay has been unavoidable. For a start, you all needed rest – your last encounters with the enemy left you all on the verge of collapse. And now Amanjit has made the breakthrough and can use the astras, he must be trained: you know this. Deepika too has work to do: she must learn to control and channel her fury, and to mask herself so that she is not revealed to Ravindra.’

Vikram nodded gloomily. ‘And just to make life more interesting, we also have to prevent Uncle Charanpreet from getting all Amanjit’s mum’s money, and Tanita from getting all Dad’s money. And we have to find Sue Parker. And clear our names over Sunita’s death.’ He sighed wearily. ‘I barely know where to start.’

Vishwamitra grinned through broken teeth. ‘Yes, you do have a few things to focus on – but I will give you this advice: don’t let the magnitude of your tasks overwhelm you. Great journeys are made up of small steps, Chand, and small steps are always achievable.’

Vikram smiled. ‘You’re right as usual, Guru-ji.’ He stood up and stretched, then picked up a bow and strung it. ‘I’d better get back to my drills.’ He grinned mischievously. ‘Is there anything you’d like demolished?’

*

They set up a broken wagon in a field outside the town. Mythic Pushkar was eerily devoid of humanity, and perhaps all the better for it – there were no roads or refuse-pits, no continual rumbling traffic or constantly smoking fires. This was still a pristine place of gentle breezes and clean streams, plentiful birds and wildlife. Snakes coiled on rocks; lizards basked. Foxes would steal past, and deer gambolled in the glades. It would be an easy place to live.

But Vikram knew he’d have no peace until he saved Rasita and slew his Enemy. Maybe when all this is done, I’ll live here in the myth-lands, happily ever after . . . But he couldn’t picture such a time. In life after life, he’d failed – why should this one be any different?

He readied his bow, drew it and awaited Vishwamitra’s command.

‘Aindra-astra!’ the old sage shouted.

Vikram muttered the incantation and fired, and his arrow burst apart as it flew, becoming a vast shower of shafts that arced and then slammed into the wagon and the area about it. He’d split it into at least four dozen arrows.

‘Focus, Chand!’ cried Vishwamitra; Vikram knew it was at best a moderate effort – he’d achieved more. ‘Agniyastra!’

This time the arrow burst into flames as it flew, striking the wagon like a rocket, blasting a hole in its side and setting it alight.

‘Varuna-astra!’ the sage yelled, barely giving him time to examine the results, and the next arrow became a torrent of water that extinguished the flames.

Vikram was panting a little more now, as each arrow drew something from him. Legend said that the astras were gifts of the gods, but to Vikram, the vital energy that empowered his astras had always come from within; he’d never sensed any divine presence when using them. They left him tired, hollowed out inside, as if the marrow of his bones had been sucked out.

‘Naga-astra!’

His next shaft became a snake, a common brown, that struck a pole beside the wagon and wrapped itself around, biting the pole, then slithering down it and wriggling away. In a few minutes, it would be an arrow again, lying in the dirt, twisted and unusable.

‘Nagapastra!’

This time the arrow split into a host of snakes that hammered against the wagon and lay there stunned, then twisted into a pile of wood shavings.

‘Vavayastra!’

The arrow vanished, but a vicious gust of wind slammed against the wagon and flipped it over and over before dissipating.

‘Suryastra!’

A brilliant light that outshone the sun lit the field like a flare, and both men had to shield their eyes.

‘Good, Chand, good!’ the sage called. ‘Now the vajra!’

Vikram fired the arrow straight up and it exploded far above into a bolt of lightning that blasted the wagon in a dazzling flash that looked like a tear in the fabric of the world. His hair stood on end as the current earthed, and when he could open his eyes again, what was left of the wagon was gently smouldering, although sparks were still leaping on the metal parts.

Vishwamitra laughed aloud. His dreadlocks had lifted about him from the static charge, looking like rays of a grimy sun. The old guru muttered a word and earthed the current through his wooden staff, causing his locks to flop back down about his face. He chuckled merrily. ‘You are a shocking pupil, Chand,’ he joked, as he always did at this point in the routine. ‘Now – the mohini!’ He gestured, and a gaudy bipedal reptile, human-sized and brandishing a sword, appeared a hundred yards away, r. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...