- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

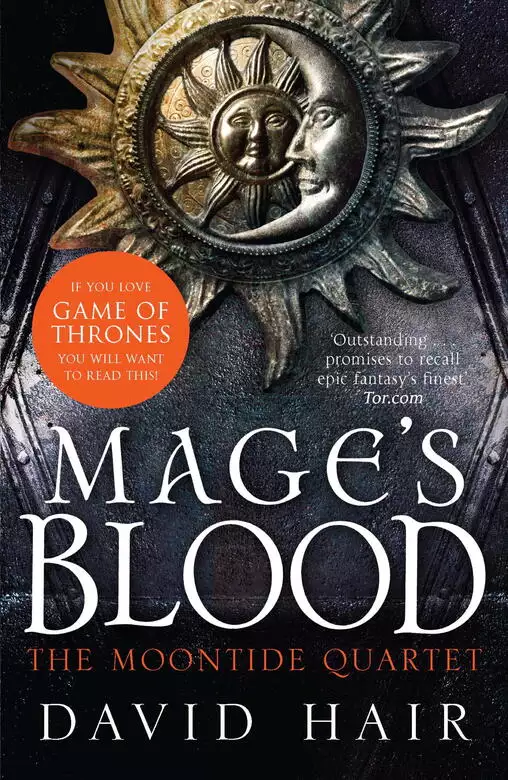

David Hair is the award-winning writer of two young adult fiction series, The Aotearoa and The Return of Ravana (based on the Vedic epic The Ramayana). Mage's Blood, the first volume of a series called The Moontide Quartet, is Hair's first work of adult fantasy. In a starred review of Mage's Blood, Publisher's Weekly said, "This multilayered beginning to the Moontide Quartet plunges readers into a taut network of intrigue and mystery that tightens with each chapter. Hair portrays a stark and beautiful world breaking apart, with both good and evil characters desperate to reshape it through magic, war, and treachery. This strong debut should draw in fantasy readers of all stripes."

Most of the time the Moontide Bridge lies deep below the sea, but every twelve years the tides sink and the bridge is revealed, its gates open for trade. The Magi are hell-bent on ruling this new world, and for the last two Moontides they have led armies across the bridge on "crusades of conquest." Now, the third Moontide is almost here, and this time the people of the East are ready for a fight…but it is three seemingly ordinary people that will decide the fate of the world.

Release date: September 27, 2012

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Mage's Blood

David Hair

ORDO COSTRUO COLLEGIATE, PONTUS

Nimtaya Mountains, AntiopiaJulsept 9271 Year until the Moontide

As the sun stabbed through a cleft in the eastern mountains, a thin wail lifted from a midden. The refuse heap lay downwind of a ramshackle cluster of mud-brick hovels. The quavering cry hung in the air, an invitation to predators. A lurking jackal soon appeared, sniffing warily. In the distance others of his kind yowled and yapped, but this close to prey, he moved in silence.

There: a bundle of swaddled clothing amidst the waste and filth, jerking spasmodically, tiny brown limbs kicking free. The jackal looked around then trotted forward cautiously. The helpless newborn went still as the beast loomed over it. It did not yet understand that the warm embracing being that had held it would not return. It was thirsty and the cold was beginning to bite.

The beast did not see a child; it saw food. Its jaws opened.

An instant later the jackal was hurled through the air, its hindquarters smashing against a boulder. It writhed agonisingly and tried to run, sliding down the slope it had so gracefully ascended, its eyes flashing about, seeking the danger it had never even sensed. One hind leg was shattered; it didn’t get far.

A ragged bulk wrapped in cloth rose and glided towards the beast, which snapped and snarled as an arm holding a rock emerged and rose and fell. There was a muffled crunch and blood splattered. From amidst the filthy cloth a face emerged, a leathery-faced old woman with wiry iron hair. She bent until her lips were almost touching the jackal’s muzzle.

She inhaled.

Later that day, the old woman sat cross-legged in a cave high above an arid valley. The land below was stark and jagged, layers of shadow and light playing amongst rocky outcroppings. She lived alone, with none to wrinkle their nose in distaste at her unwashed stench, nor to avert their eyes from her wizened face. Her skin was dark and dry, her tangled hair grey, but she moved with grace as she built up the fire. Smoke was cleverly funnelled up a cleft in the rock and out – one of her many great-nephews had carved the chimney, and though she didn’t remember his name, a face floated to mind.

Methodically she spooned water into the tiny puckered mouth of the newborn baby, one of dozens abandoned each year by the villagers, unwanted and doomed from their first breath. All they asked of her was that she saw them on their way to paradise. The villagers revered her as a holy woman and often sought her aid; the Scriptualists tolerated her, turning a blind eye – for they too had needs, their own dead to placate. From time to time a zealot tried to drive away the ‘jadugara’ – the witch – but they seldom lasted long – condemning her tended to prove unlucky. And if they came in force she was very hard to find.

The villagers wanted her intercessions with the ancestors. She told them what they needed to hear and in return she was given food and drink, clothes and fuel – and their unwanted children. They never asked what became of them – life was harsh here and death came easy. There was never enough for all.

The child in her lap squalled, its mouth questing for sustenance as she looked down at it without emotion. She too was a jackal, of another sort, and great-grandmother of her own pack. When she was younger, she’d had lovers, and conceived once; a girl who became a woman and bred many more. The jadugara still watched over her ancestors, pieces in her unseen game. She had dwelt here longer than any realised, pretending to age, die and be replaced, for centuries. The crypt-cavern in which her predecessors were supposedly buried was empty – at least of her own predecessors; instead she interred the bones of dead strangers. From time to time she would leave to wander the world, wearing scores of faces and names, moving through young woman to old crone like some season-goddess of the Sollan faith.

She did not feed the child, for that would be wasteful and nothing here could be wasted, not in this place and especially not by her, who purchased power so dearly. She tossed a pinch of powder into the flames and watched them change colour from pale orange to a deep emerald. The air temperature fell in seconds, though the flames flared higher. The smoke thickened and the night inhaled watchfully.

The time had come. She picked up a knife from the pile of knickknacks at her knee and pressed it against the baby’s tiny chest. Her eyes met the child’s briefly, but she did not reflect or regret. She’d lost those emotions somewhere in her youth. She had done this more than a thousand times in her long life, in dozens of lands, on two continents; for her it was as necessary as food or water.

She pushed the blade through the baby’s ribs, silencing the child’s brief cry. The little mouth opened and the hag placed her lips to the infant’s mouth. She inhaled … and she was replenished, more than by the jackal. If the child had been older she would have got more, but she would take whatever came her way.

She placed the dead baby to one side, meat for the jackals – she had taken what she needed. She let the smoky energy she had ingested settle inside her. It recharged her as only the swallowed soul of another could. Her vision cleared, her vitality renewed. Replenished, she rekindled her awareness of the spirit world, which took some time – the spirits knew her, and would not approach unless compelled. Some she had bound to her will though, and from these she selected a favourite. She crooned his name; ‘Jahanasthami,’ as she sent out sticky tendrils of power. She poked at the fire, stirring the embers into flame, and added more powders, making the smoke run thicker. ‘Jahanasthami, come!’

It was long minutes before the face of her spirit-guardian formed in the smoke, blank as an unpainted Lantric carnival mask. The eyes were empty, the mouth a blackness. ‘Sabele,’ it breathed. ‘I felt the child die … I knew you would call.’

She and Jahanasthami communed, images from the spirit’s consciousness streaming into hers: places and faces, memories, questions and answers. When the spirit was confounded by one of her enquiries it consulted others, then passed on the responses. They were a web of souls, connected by uncountable strands, containing so much knowledge that a mind might burst before it could take it all in. But Sabele tried, straining through the endless trivia and minutiae of millions of lives, seeking the nuggets of information that would shape the future. The jadugara shook with the effort.

Hours passed – to her, they were aeons, in which galaxies of information were born, flowered, collapsed and perished. She floated in seas of imagery and sound, immersed in the vast panoply of life, seeing kings and their servants conferring, priests haggling and merchants praying. She saw births and deaths, acts of love and murder. Finally she glimpsed the face she was seeking through the ghost-eyes of a dead Lakh girl haunting a village well – just a tiny instant, when the ghost saw a face revealed by the twitch of a curtain, before a flare of wards buffeted her away. That mere flash was enough, and Sabele moved closer, from spirit to spirit, hunting. She could feel her quarry, the way a spider sensed a distant trembling at the edge of its web, and at last she was certain: Antonin Meiros had finally made his move. He had come south from his haven in Hebusalim, seeking a way to avert war – or at least survive it. How ancient he looked; she remembered him in his youth: a face burning with energy and purpose. She’d barely escaped him then, when he and his order had slaughtered her kindred – her lovers, her bloodline, almost extinguished. Better you still think me dead, magus.

She banished Jahanasthami with an irritable gesture. So, the great Antonin Meiros has decided to act at last. She had been poking around in the constantly shifting potentials of the future long enough to know what he sought; it only surprised her that he had waited so long to act. Only one year remained until the Moontide and the carnage it would bring. It was late in the game, but Meiros’ other options had been torn away.

He and Sabele were Diviners; both had seen the likely futures before them. They had crossed mental blades for centuries, worrying away at the strands of the future. She could hear his questions and felt the answers he got – she had sent him some of those answers herself, lies tangled around suppositions, hooks on gossamer threads.

Yes, Antonin, come south – take the gift I have prepared for you! Taste of life again. Taste of death.

She tried to laugh and found herself weeping instead, in anguish at all that was lost, or some other emotion she had forgotten she could feel. She didn’t analyse it, merely tasted it and savoured the novelty.

The sun rose high enough to pierce the cavern and found her still there: an old spider tangled in ancient webs. Beside her the tiny corpse of the child lay cold.

Urte is named for Urtih, an earth god of the ancient Yothic people. There are two known continents, Yuros and Antiopia (or Ahmedhassa). Some scholars have speculated that, due to certain similarities in primitive artefacts and some commonality of creatures, they were once joined through the Pontic Peninsula. This is still unproven, but what is certain is that without the power of the magi, there would be no intercourse between the continents now, as they are divided by more than three hundred miles of impassable sea. We surmise a prehistoric cosmic incident which caused Lune, the Moon, to move into a closer orbit, rendering the seas more turbulent, preventing sea-travel and destroying significant landmass.

ORDO COSTRUO COLLEGIATE, PONTUS

Pallas, North Rondelmar, on the continent of Yuros2 Julsept 9271 Year until the Moontide

Gurvon Gyle pulled up the hood of his robe like a penitent monk: just another anonymous initiate of the Kore. He turned to his companion, an elegant silver-maned man who was stroking his beard thoughtfully, staring out the grilled window. Shifting light caught on his face, making him look ageless. ‘You’ve still got the governor’s ring on, Bel,’ Gyle remarked.

The man started out of his reverie and pocketed the easily identifiable ring. ‘Listen to the crowds, Gurvon.’ His voice wasn’t exactly awed, but certainly impressed, which seldom happened. ‘There must be more than a hundred thousand citizens in the square alone.’

‘I’m told more than three hundred thousand will witness the ceremony,’ Gyle said, ‘but not all of them will be watching the parade. Pull up your hood.’

Belonius Vult, Governor of Noros, smiled wryly and cowled himself with a soft sigh. Gurvon Gyle had built a career on anonymity, but Vult hated it. Today was not an occasion for display, though.

Heralded by a soft knock at the door, another man slid into the tiny room. He was slender, with the olive skin and curling black hair of a Lantrian, clad in sumptuous red velvets and bearing an ornate crozier. His soft, oval face had full, womanish lips and narrow eyes. Being near him made Gyle’s skin crawl at the tingling sensation of gnosis-wardings. Paranoia ruled the Church magi more than most. The bishop flicked back his tangle of black curls and proffered a ring-encrusted hand. ‘My lords of Noros, are you ready to witness the Blessed Event?’

Vult kissed the bishop’s hand. ‘Eagerly ready, my Lord Crozier.’ All bishops of the Kore forsook their family and took the surname Crozier, but this man was kin to the Earl of Beaulieu and was accounted one of the rising stars of the Church.

‘Call me Adamus, gentlemen.’ The bishop leant his crozier against the wall and smiled like a child playing dress-up as he pulled up the hood of his identical grey cloak. ‘Shall we go?’

The bishop led them into a darkened passage and up a crumbling stair. With every step the noise grew: the hum and buzz of the people, the blare of trumpets, the rumble of drums, the chanting of the priests and shouting of the soldiers, the tramp of the thousands of boots. They could feel it through the stonework; the air itself seemed to vibrate against their skin. Then they topped the stairs and found themselves on a tiny recessed balcony overlooking the Place d’Accord. The roar became a wall of sound that buffeted their senses.

‘Great Kore!’ Gyle shouted at Vult, who was smiling in wonder. Neither man was unworldly, but this was something more than either had seen. This was the Place d’Accord, the heart of the city of Pallas, as Pallas was the heart of Rondelmar, which was the heart of Yuros: the Heart of the Empire. This mighty square was the theatre upon which the endless play of politics and power was staged, before a mob whose size was frightening. Giant marble and gold statuary dwarfed the people clustered beneath and on them, like giants come to witness the pageant. Column after column of soldiers marched past, the tramp of the legionaries a drumbeat, a pulse of power. Windships circled above, giant warbirds floating in defiance of gravity, casting massive shadows beneath the noonday sun. Scarlet flags billowed in the soft northerly winds, bearing the Lion of Pallas and the sceptre and star of the Royal House of Sacrecour.

Gyle let his eyes drift to the royal box, some two hundred yards to his left, to where the legionaries directed their straight-armed salutes as they passed. Tiny figures in scarlet and glittering gold presided from above: His Royal Majesty the Emperor Constant Sacrecour and his sickly children. Assorted Dukes and Lords of this and that, Prelates and magi too, all come to witness this never-before-seen event.

Today, a living saint would be inaugurated. Gyle whistled softly, still amazed that someone had the nerve for such blasphemy, but to most here, judging by the joyous and triumphal mood of the crowd, it was deemed right and good.

A cavalry detachment high-stepped past, followed by a dozen elephants, captured on the last Crusade. Then came the Carnian riders, guiding their huge fighting-lizards between the walls of onlookers, ignoring the collective gasps of the crowds. The gaudy reptiles snapped and hissed whilst their riders maintained iron discipline, staring straight ahead except when they too swivelled to salute the emperor.

Gyle remembered what it was like to face such a force in battle and shuddered slightly. The Noros Revolt: a débâcle, a very personal nightmare. It had been the making of him, even as it stripped away both innocence and morality, and for what? Noros was once more part of the Imperial Family of Nations, for all the good it did them. For the empire it had been a blip, a momentary stalling of their conquests, but for Noros, the wounds still festered.

Gyle banished these thoughts. No one outside of Noros cared any more, and certainly no one here. He followed the bishop’s pointing finger and dutifully marvelled as the Winged Corps swooped over the Place d’Accord, dozens of flying reptiles in serried ranks coming over the roof of the Sacred Heart Cathedral, battle-magi saddled behind the riders, and dipping before the royal box while the crowds screamed in awe and no little fear. Jaws longer than a man snapped, foot-long teeth gnashed and many of the winged constructs belched fire as they roared: impossible creatures made real by the magi.

How did we ever think we could defeat them?

After that came trumpets and a sudden silence as white flags rose about the royal box – the cue for the populace to still their tongues, for the emperor was to speak. Obedient to a man, the people fell silent as the small, slender shape on the throne rose to his feet and stepped to the front of the royal podium.

‘My People,’ Emperor Constant began, his high-pitched voice gnostically amplified throughout the square, ‘my People, today I am filled with pride and awe. Pride, at the assembled grandeur of we, the Rondian people! Rightly are we acclaimed the greatest nation upon this Urte! Rightly are we known as Kore’s Children! Rightly do we sit in judgement on the rest of mankind! Rightly are you, the least of my children, of greater worth to God than all other peoples! And awe, that we have achieved so much in the face of all adversity. Awe, that we have been chosen by Kore himself for his mission!’

Constant went on exalting his people – and by implication himself – cataloguing their glories from the overthrow of the Rimoni Empire and the conquest of Yuros to the Crusades across the Moontide Bridge and the crushing of the infidels of Antiopia.

Gyle felt his attention drift away from the emperor’s slant on history. He counted himself fortunate, one of the few who had been educated in something closer to the truth. The Arcanum he’d attended had been more secular and less partisan. The tale he knew was that as recently as five hundred years ago Yuros had been fragmented, its greatest power, the Rimoni Empire, controlling barely a quarter of the landmass, though that encompassed Rimoni, Silacia, Verelon and all of Noros, Argundy and Rondelmar. Wars were constant; dynasties plotted and warred in Rym, the capital. Various faiths, now labelled pagan, struggled for supremacy. Plagues came, famines went. The seas roared, impassable. No one even dreamed that there was another continent beyond the eastern seas.

Then five hundred years ago, everything changed: Corineus came like a blazing comet and set the world alight. Corineus the Saviour, though he was born Johan Corin, son of a noble family of the border province of Rondelmar. He abandoned the savage gentility of the courts for a simpler, rustic life on the road. Johan Corin travelled, preaching of free love and other such idyllic notions, attracting a band of followers that over time burgeoned into nearly a thousand young people. The lost and impressionable swarmed to him and his promises of salvation in the next life and endless debauchery in this one. His people swarmed over the countryside, marked out as troublemakers, until the day when they descended upon one particular township, who panicked and called upon a nearby legion camp for help. The army agreed that the time had come to end the blasphemies of Johan Corin and his followers. That night Corin’s camp was surrounded by a full legion, and at midnight, the soldiers closed in to make the arrests.

What happened next passed into legend and became scripture: there were lights and voices, and the legion died, to a man, in a thousand different ways. So did many of Corin’s followers, including Corin himself, murdered by his sister-lover Selene. But there were survivors, and they were transfigured: each one had the power of a demi-god, wielding fire and storm, throwing boulders and channelling lightning. They became the Blessed Three Hundred, the first magi.

Abandoning Corin’s principles of love and peace to take revenge on the town (now conveniently remembered as a ‘wicked place’) in an orgy of destruction. Then, realising what they now were, they allied themselves with a Rimoni Senator and formed a new movement that became an army capable of annihilating whole legions without losing a man. They destroyed the Rimoni, razed Rym and made the world anew. They created the Rondian Empire.

The Three Hundred attributed their powers to Johan Corin, claiming he was an Intercessor with God, who had bargained away his own life to gain magical powers for his disciples. They set about claiming the mortal world as their own. Being young and almighty, they slept with whomever they desired, in any land they came to. At first they did not care that the powers diminished in their children the less they bred true, but as their offspring spread throughout Yuros, claiming fiefdoms, and their understanding of their powers grew, they started colleges to teach each other, and they founded a church, and preached of their own divinity to the population.

Now, five centuries later, thousands bore the sacred blood of the Blessed Three Hundred: the magi. Their rule was embodied in the Imperial Dynasty, all descendants of Sertain, who took Corin’s place as leader after the transfiguration, and currently vested in Emperor Constant Sacrecour. Gyle himself could trace his ancestry directly to one of those Three Hundred. I am of this, he thought. I am magi, though I am also of Noros. He glanced at Belonius Vult and then at Adamus Crozier, magi also: rulers of Urte.

Adamus gestured to the lower end of the Place d’Accord as if this were a show he was compering. A massive statue of Corineus stood there, his arms flung wide, just as they had found him the morning after the Transfiguration: dead, with his sister’s dagger in his heart. Every one of the Three Hundred claimed to have spoken to and received instruction from Corin after his death. Some said they had seen his sister Selene in their visions, screaming foul words, though she had been nowhere to be found when they came to themselves at dawn with the legion lying dead about them. Their accounts became Scripture: Johan had guided them through the transfiguration, then been murdered by his corrupt sister Selene. He was the son of God and she was the whore-witch of Perdition. He become Corineus, the Saviour, revered everywhere; she became Corinea, the Accursed.

From the breast of the massive statue of Corineus a rose-gold light began to form, shimmering as it grew. The crowd gasped in anticipation and awe as the light became brighter and brighter, casting its brilliance over the square. Gyle could see tears on the faces of many.

Within the rosy light a shape formed, a woman clad in a white gown that looked deceptively simple, until Adamus whispered that it was made entirely of diamonds and pearls. She walked slowly out onto the platform formed by the giant golden dagger piercing the statue’s heart: a woman about to be proclaimed a living saint. The entire crowd emitted an awestruck sob, as if all their hopes and dreams rested in her alone. They gasped as she stepped from the golden dagger into the air and floated down the square, some sixty feet above the crowd, towards the royal box. The people cried and cheered at this simple feat that any half-trained mage could accomplish.

Adamus Crozier winked, as if to say ‘behold the theatre’. Gyle kept his face guarded.

The woman drifted past them, her palms pressed together in supplication, a sea of faces following her progress as she floated above them. I hope she’s wearing her best underwear, Gyle found himself thinking, then stilled his mind. Mocking these people, even in the privacy of your mind, was a dangerous habit to fall into. Minds were not inviolate.

The woman floated toward the imperial throne, where Grand Prelate Wurther, Father of the Church, rose stiffly to receive her, his attendants about him. She bent her knees as she landed, hands clasped in humble prayer. The crowd cheered, then fell silent again as the Grand Prelate raised his hand.

Adamus Crozier tugged at Gyle’s sleeve. ‘Do you need to see more?’ he whispered.

Gyle looked at Vult, then shook his head faintly.

‘Good,’ said Adamus. ‘I have a fine scarlo awaiting us below, and we have much to discuss.’

Before they left, Gyle allowed himself to gaze long and hard at the face of the emperor, the young man they would meet in person tomorrow. Using his mage-trained sight he pulled his gaze in closer, carefully studying the man who ruled millions. Constant’s face was a study in pride, envy and fear, ill-hidden behind a mask of piety. Gyle almost felt pity for him.

After all, how was one supposed to react when one’s living mother had just become a saint?

The following day Gyle found himself whiling away the last few minutes before his audience in the lush palace gardens. As ever, he was the outsider, the interloper in paradise. He turned his collar against the light drizzle and paced a secluded path, his mind elsewhere. He stood out here because he wasn’t dressed in vivid finery. This season the fashions were bright, Eastern-inspired, and throughout the gardens were noblemen affecting martial attire. The Third Crusade was approaching, so it was fashionable once more to look like a man of war, but Gyle’s weathered leathers made him look like a thrush in a parrot’s cage. He wore a sword himself, but his had a razor-sharp blade and a well-worn grip. His lined features, tanned to a deep brown by the desert sun gave him a sinister air amidst these pallid northerners. But still he was careful not to cross the path of any of the young men or women, despite their polished effeminacy and mincing manners: every person in this garden was mage-born, with the power to destroy a squad of soldiers with a thought. He could too, if he needed to, but there was no gain to be had in brawling with a young mage-noble in the emperor’s gardens.

Belonius Vult appeared at the entrance to the gardens and gave an impatient wave.

Well then. With small steps, big things begin.

The governor’s smooth features crinkled in mild annoyance as he took in Gyle’s rough-clad appearance. Vult himself was clad in a silver-blue silken robe, the epitome of the well-dressed magus. Gyle had known him for decades, and had never seen him look less than sumptuously immaculate. Belonius Vult, the Governor of Noros in the name of his Imperial Majesty. Others knew him as the traitor of Lukhazan, the one general of the Noros Revolt who now served the empire in a high post.

‘Could you not have at least thrown on a clean tunic, Gurvon?’ Belonius remarked. ‘We are appearing before the emperor – and more importantly, his newly sainted mother.’

‘It’s clean,’ Gyle said. ‘Well, washed anyway. The dirt is ingrained. It’s what they expect of me: an uncouth southerner, fresh from the wilds.’

‘Then you look the part. Come, we are expected.’ If Vult had any nerves, they were well hidden. Gyle could not remember Magister Belonius Vult looking discomforted very often, not even during the surrender of Lukhazan.

They traversed a tangle of marble courtyards and rosewood-panelled arches, passing statues of emperors and saints, bowing to lords and ladies as they penetrated the Imperial Palace through doors that few were permitted to pass. Strange creatures walked the halls unattended: hybrid creatures, gnosis-constructs from the Imperial bestiary. Some were made to resemble creatures of legend, griffins and pegasi, but others were nameless figments of their makers’ imagination.

A final door led to a chamber where Imperial Guardsmen with winged helms stood like statues. A chamberlain bade them set aside their periapts, the channelling gems that enhanced the use of the gnosis. For Belonius, this was the crystal topping his beautiful blackwood and silver staff; for Gyle it was a plain onyx on a leather string tucked inside his shirt. He leant his sword against the wall and hung the gem from its hilt. He shared one final glance with Vult. Ready?

Vult nodded, and together, the two Noromen entered the inner sanctum of their conquerors.

Within was a large round chamber with walls of plain white marble, with scenes of the Blessed Three Hundred set in relief. A statue of Corineus ascending to Heaven hung above the table, slowly rotating with no visible support. The Saviour was gazing upward, his face rapt in the moment of death. Lanterns held in either hand illuminated the room. A round table made of heavy oak and polished to mirror-sheen had nine seats set about it, in a nod to the traditions of the north: the Schlessen legend of King Albrett and his Knights. However, Emperor Constant had made something of a mockery of this legendary symbol of equality by seating himself on a carved throne set on a dais above the table, dominating the room. It was decorated with Keshi gold and camel-bone, if Gyle wasn’t mistaken: plunder from the last Crusade.

The doorman announced, ‘Your Majesties, may I present Magister-General Belonius Vult, Governor of Noros; and Volsai-Magister Gurvon Gyle of Noros.’

His Imperial Majesty Constant Sacrecour looked up from beneath beetled brows and frowned. ‘They’re Noromen,’ he complained in a whining voice. ‘Mother, you never said they were Noromen.’ He shifted uncomfortably in his heavy ermine-lined crimson robes. He was a thin man in his late twenties, but he acted younger, and his face was permanently pursed into an expression of petulant distrust. His beard had been nervously twisted out of shape and his hair was lank. He gave the impression he would rather be elsewhere, or at least better-amused.

‘Of course I did,’ replied his mother brightly. The Sainted Mater-Imperia Lucia Fasterius remained seated, but she gave them both a welcoming smile, surprising Gyle, who’d expected a colder woman. She had lines about her eyes and mouth that most mage-women’s vanity would not tolerate, and she wore an unpretentious sky-blue dress, her only adornment a golden halo-circlet pushing back her blonde hair. She looked li

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...