- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

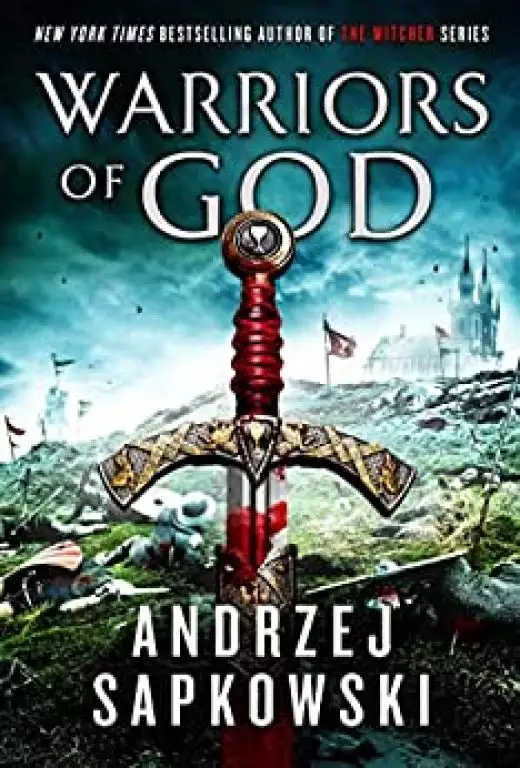

WARRIORS OF GOD, the second volume of the Hussite Trilogy by Andrzej Sapkowski, author of the bestselling Witcher series, depicts the adventures of Reynevan and his friends in the years 1427-28 as war erupts across Europe.

Reynevan begins by hiding away in Bohemia but soon leaves for Silesia, where he carries out dangerous, secret missions entrusted to him by the leaders of the Hussite religion. At the same time he strives to avenge the death of his brother and discover the whereabouts of his beloved. Once again pursued by multiple enemies, Reynevan is constantly getting into and out of trouble.

Sapkowski's deftly written novel delivers gripping action full of numerous twists and mysteries, seasoned with elements of magic and Sapkowski's ever-present - and occasionally bawdy - sense of humour. Fans of the Witcher will appreciate the rich panorama of this slice of the Middle Ages.

Release date: August 24, 2021

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Warriors of God

Andrzej Sapkowski

CHAPTER ONE

In which Prague stinks of blood, Reynevan is followed, and then – by turns – becomes bored by routine, is full of recollections and longing, celebrates, fights for his life and drowns in a feather bed. And all the while, Europe turns somersaults, gambols and frolics.

Prague stank of blood.

Reynevan sniffed both sleeves of his jerkin. He had only just left the hospital, and while there – as is usual in a hospital – blood had been let from almost everyone, boils were regularly lanced and amputations took place with a frequency worthy of a better cause. His clothing might have absorbed the smell; there’d have been nothing unusual about that. But his jerkin just smelled like a jerkin. And nothing else.

He raised his head and sniffed. From the north, over on the left bank of the River Vltava, came the smell of dried weeds being burned in orchards and vineyards. Moreover, from the river came the smell of mud and rotting flesh – the weather was hot, the water level had dropped considerably and the exposed banks and dried-out sandbars had for some time been supplying the city with unforgettable olfactory impressions. But this time it wasn’t the mud that stank. Reynevan was certain of it.

A light and changeable breeze was blowing intermittently from the Poříčí Gate to the east. From Vitkov. And the ground at the foot of Vitkov Hill might indeed have been giving off the smell of blood, since plenty of blood had soaked into it.

But that couldn’t be possible. Reynevan adjusted the shoulder strap of his bag and walked briskly down the lane. The smell of blood couldn’t be coming from Vitkov. Firstly, it was quite far away. Secondly, the battle had been fought in the summer of 1420. Seven years before. Seven long years before.

He passed the Church of the Holy Cross, making good speed, but the stench of blood hadn’t faded. On the contrary, it had had grown more intense. For now, all of a sudden, it was coming from the west.

Ha, he thought, looking towards the nearby ghetto, stones aren’t like soil, old bricks and plaster remember much, much lingers on in them. What they absorb stinks for a long time. And over there, outside the synagogue and in the streets and houses, blood flowed even more copiously than in Vitkov, and a little more recently. In 1422, during the bloody pogrom, at the time of the upheaval that erupted in Prague following the execution of Jan Zelivsky. Enraged by the execution of their popular tribune, the people of Prague had risen up to seek revenge, to burn and kill. The Jewish district, as usual, took the brunt of it. The Jews had nothing at all to do with Zelivsky’s death and weren’t in any way responsible for his fate. But who cared?

Reynevan turned beyond the graveyard of the Church of the Holy Cross, passed by the hospital, entered the Old Coal Market, crossed a small square and ducked into the gateways and narrow backstreets leading to Dlouha trida. The smell of blood had faded into a sea of other scents, for the gateways and backstreets bore every imaginable stench.

Dlouha trida, however, greeted him with the powerful and heady aroma of bread. As far as the eye could see, celebrated Prague bread and rolls lay golden and fragrant on bakers’ stalls and counters. Although he had breakfasted in the hospital and wasn’t hungry, he couldn’t resist and bought two fresh rolls at the first stall he came across. The rolls – called callas – were shaped so erotically that, for a while, Reynevan wandered along Dlouha trida in a dream, bumping into stalls, lost in thoughts that raged like desert winds about Nicolette. About Katarzyna of Biberstein. There were several extremely attractive women of various ages among the passers-by he bumped into and jostled, lost in thought. He didn’t notice them. He apologised absent mindedly and went on, by turns chewing a calta and staring at it spellbound.

The stench of blood in the Old Town Square brought him to his senses.

Ah well,thought Reynevan, finishing the calta,perhaps that’s not so strange – blood is nothing new for these streets.Jan Zelivsky and nine of his companions were executed right here, in the old town hall, having been lured here that Monday in March. After that treacherous deed, the town hall floor was washed, and red foam streamed under the doors and flowed – it was said – all the way to the pillory in the centre of the town square, where it formed a huge puddle. And soon after, when the news of the tribune’s death provoked an outburst offury and the lust for revenge in Prague, blood flowed along all the surrounding gutters.

People were walking towards the Church of Our Lady before Tyn, crowding into the courtyard leading to its doors. Rokycana willbe preaching, thought Reynevan. It’ll be worth listening to what Jan Rokycana has to say, he thought. It’s always paid to listen toJan Rokycana’s sermons. Always. Particularly now, at a time when the current events are supplying subject matter for sermons at a simply alarming rate. Oh, he has plenty to preach about. And it’s worth listening to.

But there’s no time. There are more pressing matters, he thought.

And there’s a problem. Namely, that I’m being followed.

Reynevan had become aware of being followed quite some time before. Right after leaving the hospital, by the Church of the Holy Cross. His pursuers were cunning, kept out of sight and hid themselves very adeptly. But Reynevan had cottoned on. Because it wasn’t the first time.

He knew-in principle-who was following him and on whose orders they were acting. Although it wasn’t especially important.

He had to lose them. He even had a plan.

He entered the thronged, smelly, noisy Cattle Market and mingled with the crowd heading towards the Vltava and the Stone Bridge. He needed to vanish and there was a good chance of doing so in the crowded bottleneck on the bridge, in the narrow corridor linking the Old Town with the Lesser Qyarter and Hradcany, in the hubbub and crush. Reynevan wove through the crowd, jostling passers-by and earning insults.

‘Reinmar!’ One of the people he bumped into, instead of call ing him a ‘whoreson’ like the rest, greeted him with his baptismal name. ‘By God! You, here?’

‘Indeed. Hey, Radim … What’s the bloody stink?’

‘It’s clay and sludge.’ Radim Tvrdik, a short and not very young man, pointed at the bucket he was lugging. ‘From the riverbank. I need it … For you-know-what.’

‘I do.’ Reynevan looked around anxiously. ‘I do, indeed.’ Radim Tvrdik was – as the enlightened few knew – a sorcerer.

Radim Tvrdik was also – as even fewer members of that enlightened circle knew – obsessed with the idea of creating an artificial person, a golem. Everybody – even the more poorly enlightened – knew that the only golem ever to have been created was the work of a certain Prague rabbi whose name, probably misspelled, was given as ‘Bar Halevi’ in surviving documents. Long ago, that Jew, so the story went, used clay, sludge and mud scooped from the bottom of the Vltava to make the golem. However, Tvrdik and he alone – presented the view that the causative factor was played here not by ceremonies and spells, which were in any case well known, but rather by a specific astrological configuration that acted on the sludge and clay in question and their magical properties. However, having no idea what the precise planetary configuration might be, Tvrdik operated using trial and error, gathering clay as often as he could, hoping one day to finally chance upon the right kind. He also took it from various places. But that day he had gone too far; judging from the stench, he had taken it straight from near some shithouse or other.

‘Not working at the hospital, Reinmar?’ he asked, rubbing his forehead with the back of his hand.

‘I took the day off. There was nothing to do. It was a quiet day.’

‘Let’s hope it’s not one of the last,’ said the magician, putting down his pail. ‘Times being what they are … ‘

Everybody in Prague understood, knew what ‘times’ were being discussed. But they preferred not to talk about it and would cut short their speech. Cutting off one’s speech suddenly became widespread and fashionable. The custom demanded that the listener assume a thoughtful expression, sigh and nod meaningfully. But Reynevan didn’t have time for that.

‘On your way, Radim,’ he said, looking around. ‘I can’t stop here. And it’d be better if you didn’t, either.’

‘Eh?’

‘I’m being followed. Which is why I can’t go down Soukenicka Street.’

‘Being followed,’ said Radim Tvrdik. ‘By the usual chaps?’

‘Probably. Cheerio.’

‘Wait.’

‘What for?’

‘It isn’t wise to try to lose your tail.’

‘What?’

‘To the tailers, attempts to lose the tail are a clear sign that the tailee has a guilty conscience and something to hide,’ the Czech explained most astutely. ‘Only a thief fears the truth. It’s sensible not to go down Soukenicka Street. But don’t dodge, don’t weave around, don’t hide. Do what you usually do. Attend to your daily activities. Bore the trackers with your boring daily routine.’

‘Meaning?’

‘I’ve developed quite a thirst digging up sludge. Come to the Crayfish. Let’s have a beer.’

‘I’m being followed,’ Reynevan reminded him. ‘Aren’t you afraid-‘

‘What’s there to be afraid of?’ The wizard picked up his pail.

Reynevan sighed. Not for the first time, a Prague magician had surprised him. He didn’t know if it was their admirable calm or simply a lack of imagination, but some of the local wizards often appeared unbothered by the fact that Hussites could be more dangerous than the Inquisition to anyone who indulged in black magic. Male.ficium – witchcraft – was among the deadly sins punishable by death in the Fourth Article of Prague. The Hussites were no laughing matter where the Articles of Prague were concerned. Self-proclaimed ‘moderate’ Calixtines from Prague were the equal of radical Taborites and fanatical Orphans in that respect. Any sorcerer who was caught was put in a barrel and burned at the stake in it.

They turned back towards the town square along Knifemakers Street, then Goldsmiths Street and finally St Giles Street. They walked slowly. Tvrdik stopped by several stalls and shared some gossip with the stallholders he knew. As was standard, sentences were cut short more than once with ‘times being what they are .. .’ which was received with wise expressions, sighs and knowing nods. Reynevan looked around but couldn’t see his pursuers. They were keeping well out of sight. He didn’t know how it was for them, but he was beginning to find the boring routine deadly boring.

Fortunately, soon after, they turned from St Giles Street into a courtyard and passed through a gateway to emerge opposite the House at the Red Crayfish. And a small tavern named identi cally by the innkeeper without a scrap of imagination.

‘Well I never! Just look! Why, if it isn’t Reynevan!’

Four men were sitting at a table on a bench behind the pil lars on the ground floor. They were all moustachioed, broad shouldered and dressed in knightly doublets. Reynevan knew two of them, so he also knew they were Poles. Even if he hadn’t, he could have guessed. Like all Poles abroad, these men were conducting themselves noisily and arrogantly, with ostentatious boorishness that in their opinion would emphasise their status and elevated social position. The funny thing was that since Easter, the status of Poles in Prague was extremely low and their social position even lower.

‘Good day! Welcome, noble Asclepius!’ One of the Poles, whom Reynevan knew as Adam Wejdnar, bearing the Rawicz coat of arms, greeted him. ‘Sit you down! Sit you down, both of you! Be our guests!’

‘Why are you inviting him so readily?’ said another of the Poles, grimacing with feigned disgust. He was also a Greater Pole, known to Reynevan as Mikolaj Zyrowski and sporting the Czewoja coat of arms. ‘Do you have a surfeit of cash or some thing? And besides, the quack works with lepers! He’s liable to infect us with leprosy – or something even worse!’

‘I’m not working in the lazaretto now,’ explained Reynevan patiently, not for the first time. ‘I’m working at Bohuslav’s hospice now, here in the Old Town by the Church of Saints Simon and Jude.’

‘Yes, yes.’ Zyrowski, who knew everything, waved a dismissive hand. ‘What are you drinking? Oh, blow it, forgive me. Let me introduce you. My lords Jan Kuropatwa of Lancuch6w bearing the Szreniawa arms and Jerzy Skirmunt bearing the Odrowqi. Excuse me, but what is that fucking smell?’

‘Sludge. From the Vltava.’

* * *

Reynevan and Radim Tvrdik drank beer. The Poles were drink ing Austrian wine and eating stewed mutton and bread. They were talking ostentatiously loudly in Polish, telling each other funny stories and responding to each one with thunderous guf faws. Passers-by turned their heads away, swearing under their breath. And occasionally spitting.

Since Easter, specifically since Maundy Thursday, the Czechs’ opinion of the Poles hadn’t been too high. Indeed, their position in Prague was also pretty low and evincing a downward trend.

Around five thousand Polish knights the first time, and around five hundred the second, had come to Prague with Sigismund Korybut, Jogaila’s nephew, pretender to the Bohemian crown. Many had seen in Korybut hope and salvation for Hussite Bohemia, and the Poles had fought valiantly for the Chalice and Divine Law, shedding blood at the Battles of Karlstejn, Jihlava, Retz and Ust. In spite of that, even their Czech comrades-in arms didn’t like them, in part because the Poles routinely found hilarious the Czech language in general and Czech names in particular, but also because Korybut’s treachery had seriously damaged the Polish cause. The hope of Bohemia was thus a total failure: for the Hussite king in spe was in cahoots with Catholic lords, had betrayed the matter of sub utraque specie Commun ion and broken the Four Articles he had sworn to uphold. The plot was uncovered and foiled, Jogaila’s nephew found himself in prison rather than on the Bohemian throne, and the people began to treat Poles with downright hostility. Some of them left Bohemia at once. But some remained, thereby apparently show ing their disapproval of Korybut’s treachery and their support for the Chalice, and declaring their readiness to fight on for the Hussite cause. And what of it? The Czech people continued to dislike them. It was suspected – not without reason – that the Poles couldn’t give a stuff about the Hussite cause. It was claimed they’d stayed because, primo, they had nothing and nowhere to go back to.They had marched to Bohemia as wastrels pursued by courts and warrants, and now, to make matters worse, they had all – Korybut included – been saddled with curses and infamy. And because, secundo, they were only fighting in Bohemia in the hope of lining their pockets and gaining spoils and land. And because, tertio, they weren’t actually fighting, but rather taking advantage of the absence of the Czechs to fuck their wives.

All of those claims were genuine.

Hearing Polish spoken, a passing Praguian spat on the ground.

‘My, they really don’t seem to like us,’ observed Jerzy Skirmunt, in his comical accent. ‘Why’s that? How odd.’

‘I couldn’t give a tinker’s cuss.’ Zyrowski stuck out his chest, displaying the silver horseshoe of the Czewoja arms to the street. Like every Pole, he subscribed to the ridiculous view that as a nobleman, even though a totally impoverished one, he was equal in Bohemia to the Rozmberks, Kolovrats, Sternberks and all the other wealthy families put together.

‘Perhaps you couldn’t,’ said Skirmunt, ‘but it’s still odd, my dear.’

‘The people are astonished.’ Radim Tvrdik’s voice may have been calm, but Reynevan knew him too well. ‘Astonished to see armed knights carelessly making merry at a tavern table. These days. Times being what they are .. .’

He trailed off in accordance with the custom. But the Poles weren’t in the habit of observing customs.

‘Meaning when the crusaders are marching on you, eh?’ Zyrowski chortled. ‘With a great force, wielding fire and sword, leaving only scorched earth behind them? And any moment-‘

‘Qµiet,’ Adam Wejdnar interrupted him. ‘I shall reply thus to you, m’Lord Czech: your reprimand is misplaced. For the New Town is indeed quite empty, for when, as you said, those days came, the New Town followed Prokop the Shaven in great num bers to defend the country. So if any New Town citizen were to scoff at me, I’d keep my counsel. But not a soul went from here, from the Old Town. That’s the pot calling the kettle black.’

‘A great force is coming from the west,’ repeated Zyrowski. ‘The whole of Europe! You won’t hold out this time. It’ll be your end, your demise.’

‘Ours,’ repeated Reynevan with a sneer. ‘But not yours?’ ‘Ours, too,’Wejdnar replied morosely, gesturing for Zyrowski

to be quiet. ‘Ours, too. Regrettably. It turns out we made a rotten choice of sides in this conflict. We should have listened to what Bishop Laskarz said.’

‘Aye and I should have listened to Zbigniew Olesnicki,’ said Jan Kuropatwa, sighing. ‘And now we’re stuck here like beasts in a shambles waiting for the butcher to come. May I remind you, gentlemen, that a crusade the like of which has never been seen is heading towards us. An army of eighty thousand men. Electors, herzogs, counts palatine, Bavarians, Saxons, soldiers from Swabia, Thuringia, the Hanseatic towns, on top of that the Landfried of Plzen – why, even some mavericks from overseas. They crossed the border at the beginning of July and besieged

Stribro, which will soon fall; perhaps it already has. How far is Stribro from here? Just over twenty miles – they’ll be here in five days, by my reckoning. It’s Monday today. On Friday, mark my words, we’ll see their crosses outside Prague.’

‘Prokop won’t stop them; they’ll defeat him in battle. They are too numerous,’ said Zyrowski.

‘When the Midianites and Amalekites attacked Gilead,’ said Radim Tvrdik, ‘they were like grasshoppers in their multitude, and their camels were as numberless as the grains of sand by the sea. But Gideon, commanding barely three hundred warriors, defeated and dispersed them. For he was fighting in the name of the Lord of Hosts with His name on his lips.’

‘Yes, yes, indeed. And the shoemaker Skuba defeated the Wawel dragon. Don’t mix fairy tales up with reality, m’lord.’

‘Experience teaches us,’ added Wejdnar with a sour smile, ‘that if the Lord takes sides, it is usually with the more powerful army.’

‘Prokop won’t hold back the crusaders,’ Zyrowski repeated pensively. ‘Ha, this time, m’Lord Czech, even Zizka himself wouldn’t save you.’

‘Prokop doesn’t have a chance!’ snorted Kuropatwa. ‘I’d wager anything. This host is too mighty. Riding with this crusade are knights from the Jorgenschild, the Order of the Shield of Saint George, the flower of European knighthood. And the papal legate is reportedly leading hundreds of English bowmen. Have you heard, 0 Czech, of English bowmen? They have bows the height of a man, shoot from five hundred paces and from that distance pierce armour and puncture mail as though it were linen. Why! Such archers can-‘

‘Dosuch archers,’ Tvrdik interrupted calmly, ‘stay upright after being struck over the head with a flail? Various fine men have come here, the flower of knighthood of all descriptions, but thus far none of their heads has withstood a Czech flail. Will you take a wager on that, m’Lord Pole? I, mark you, state that when an Englishman gets whacked on the head with a fl.ail, that Englishman won’t bend his bow a second time, because that Englishman will be a deceased Englishman. If there’s any other result, you win. What shall we wager?’

‘They’ll crush you.’

‘They’ve already tried,’ observed Reynevan. ‘Last year. On the Sunday after Saint Vitus’s day. At Usti. But you were at the Battle ofUsti, Sir Adam.’

‘Aye,’ admitted the Wielkopolanin, ‘I was. We were all there.

You, too, Reynevan. Surely you haven’t forgotten?’

‘No. I haven’t.’

* * *

The sun was beating down mercilessly and visibility was poor. The dust cloud kicked up by the hooves of the attacking knights’ horses was mixed up with the thick gunpowder smoke that had filled the entire inner square of the wagon fort following the salvo. Suddenly, the crack of breaking wood and triumphant cries rose above the yelling of the soldiers and squealing of horses. Reynevan saw men in :flight spilling from the smoke.

‘They’ve broken through,’ gasped Divis Borek of Miletinek loudly. ‘They’ve rent open the wagons .. .’

Hynek of Kolstejn cursed. Rohac of Dube tried to bring his snorting horse under control. The face of Prokop the Shaven was set hard. Sigismund Korybut was very pale.

Yelling, armoured cavalry poured out of the smoke, the knights falling upon the :fleeing Hussites, knocking them over with their horses, smiting and hacking any men who hadn’t managed to shelter in the inner square of the wagons. A wave of heavy cavalry poured into the breach.

Then suddenly fire and lead spurted from cannons and trestle guns; hook guns rattled, handgonnes roared and a thick hail of bolts rained from crossbows into the throng compressed and crowded in the breach, straight into the faces of the riders and horses. Riders crashed from their saddles, horses tumbled over, men with them. As the cavalry teemed and swarmed, another salvo exploded into the mass with even deadlier effect. Only a handful of cavalrymen rode into the smoke-filled inner square and they were immediately felled with halberds and fl.ails. At once, the Czechs flooded out from behind the wagons with savage cries, catching the Germans by surprise with a sudden counter-attack and driving them from the breach in an instant. The breach was immediately barricaded with wagons, to be manned by crossbowmen and flailmen. Cannons roared again and hook-gun barrels belched smoke. A monstrance raised above the wall of wagons flashed bright gold and a standard bearing the Chalice gleamed white.

Who are the Warriors of God and His law!

Help right from God

And Trust in Him

The singing rose about the wagenburg, growing louder, more powerful and triumphant. Dust settled behind the retreating cavalry.

Rohac of Dube, knowing it was the moment, turned towards the mounted Hussites waiting in formation and raised his mace. A moment later, Dobko Puchala gestured likewise towards the Polish cavalry. A sign from Jan Tovafovsky set the mounted Moravians at battle readiness. Hynek of Kolstejn slammed his visor shut.

From the battlefield, the cries of the Saxon commanders ordering their knights to begin another charge could be heard. But the cavalry were falling back, turning their horses around.

‘They’re running awaaay! The Germans are running awaaay!’ ‘After them!’

Prokop the Shaven breathed out and raised his head.

‘Now .. .’ he said, panting heavily. ‘Now their arses are ours.’

* * *

Reynevan abandoned the company of the Poles and Radim Tvrdik quite unexpectedly – he simply stood up abruptly, said goodbye and left. A short, meaningful glance atTvrdik signalled his intentions. The sorcerer winked. And understood.

The stink of blood was all around again. Surely, thought Reynevan, it’s comingfrom the nearby shambles,from Kotce Street and the Meat Market. But perhaps it isn’t? Perhaps it’s different blood?

Perhaps it was the blood that foamed in these gutters here in September 1422, when Ironmongers Street and the streets around it were witness to fratricidal fighting, when the antag onism between the Old Town and the Tabor once again led to bloodshed. Much Czech blood had flowed in Ironmongers Street then. Enough for it to still stink.

And it was the stench of blood that sharpened his vigilance. He hadn’t seen his trackers, wasn’t noticing anything suspicious and none of the Czechs walking along the streets looked like a spy. Despite that, Reynevan permanently felt someone’s eyes on his back. The men trailing him, it appeared, weren’t yet bored with the boring routine. Very well, he thought, very well, you good-for-nothings, I’ll treat you to some more of this routine. Until you’re sick of it.

He went down Glovers Street, crammed with workshops and stalls. He stopped several times, feigning interest in the goods and looking around furtively. He didn’t see anyone following him, but he knew they were somewhere around.

Before reaching Saint Gall’s Church, he turned, entering a backstreet. He was heading towards the Karolinum, his alma mater. He enjoyed attending university debates and quodlibets as part of his routine. After having received Holy Communion under both kinds on Quasimodogeniti Sunday, the first after Easter in 1426, he had begun to regularly attend the lectorium ordinarium. Like a true neophyte, he wanted to learn the mysteries and complexities of his new religion as fully as possible, and he acquired them most easily during the dogmatic debates which were regularly organised by members of the moderate and conservative wings, grouped around Master Jan of Pribram, and members of the radical wing, drawn from men of the circle of Jan Rokycana and Peter Payne, an Englishman, Lollard and Wycliffite. But those disputes became truly impassioned when they were attended by genuine radicals, men from the NewTown. Then things became thrilling indeed. Reynevan witnessed some one defending one of Payne’s Wycliffite dogmas being called a ‘fucking Englishman’ and having beetroots thrown at him. The elderly Kristan of Prachatice, the university’s distinguished rector, was threatened with being drowned in the Vltava. And a dead cat was flung at the venerable Petr of Mladonovice. The audience gathered there often resorted to fisticuffs; teeth were knocked out and noses broken in the Meat Market near the Karolinum, too.

But some changes had occurred since those times. Jan of Pribram and his followers were revealed to have been involved in Korybut’s plot and punished by banishment from Prague. Since nature cannot bear a vacuum, the debates continued, but after Easter, Rokycana and Payne suddenly started to be considered moderates and conservatives.The men from the New Town – as previously- were considered radicals.Uncompromising radicals. There was still fighting during the debates; insults and cats were still tossed around.

‘M’lord.’

He turned. The short individual standing behind him was all grey. He had a grey physiognomy, a grey jerkin, a grey hood and grey hose. The only vivid accent about his entire person was a brand-new truncheon turned from light-coloured wood.

Reynevan looked back, hearing a slight noise behind him. The other character blocking the exit to the alley also had a trun cheon. He was only a little taller and only a little more colourful than his companion, but his face was much more repugnant .

‘Let us go, m’lord,’ said Grey, without raising his eyes. ‘Where to? And what for?’

‘Don’t o.uerer any res• istance, m’l ord.’

‘Who ordered this?’

‘Lord Neplach. Let us go.’

* * *

They didn’t have far to go, as it happened, just to one of the buildings on the southern frontage of the Old Town Square. Reynevan couldn’t work out exactly which one; the spies led him in from the back, through gloomy arcades stinking of mouldy barley, through courtyards, hallways and staircases. The interior was quite sumptuous – like most houses in that quarter, it had been taken over when the wealthy Germans who had owned it fled from Prague after 1420.

Bohuchval Neplach, called Flutek, was waiting for him in the drawing room beneath a light-coloured, beamed ceiling. A rope was tied to one of the beams. A dead man was hanging from the rope. With the toes of his elegant slippers touching the :floor. Well, almost. They were about two inches shy.

Without wasting time on greetings or other outdated bourgeois customs, barely glancing at Reynevan, Flutek pointed at the hanged man. Reynevan understood.

‘No … ‘ He swallowed. ‘That’s not him. I don’t think … No, no it isn’t.’

‘Take a closer look.’

Reynevan took a closer look, good enough to be sure that the rope digging into the swollen neck, contorted face, bulging eyes and black lolling tongue would come back to haunt him during his next few meals.

‘No.That’s not him … In any case, I can’t be sure … I saw him from the back … ‘

Flutek snapped his fingers. The servants present in the draw ing room turned the hanged man so that his back was towards Reynevan.

‘That man was sitting. Wearing a cloak.’

Flutek snapped his fingers. A moment later, the corpse, now cut down, was draped in a cloak and sitting in a curule chair – striking quite a macabre pose, bearing in mind the rigor mortis.

‘No.’ Reynevan shook his head. ‘Don’t think so. That man …

Hmm … I’d definitely recognise him by his voice-‘ ‘Regrettably, that’s not possible.’ Flutek’s voice was as cold as the wind in February. ‘If he could speak, I wouldn’t be needing you at all. Go on, get that carcass out of here.’

The order was carried out at great speed. Flutek’s orders always were. Bohuchval Neplach was the head of the Tabor’s intelli gence and counter-intelligence operations, reporting directly to Prokop the Shaven. And while Zizka was alive, directly to Zizka.

‘Be seated, Reynevan.’ ‘I’m afraid I can’t-‘ ‘Be seated, Reynevan.’ ‘Who was that-‘

‘The hanged man? It doesn’t matter in the slightest now.’ ‘Was he a traitor? A Catholic spy? He was, I gather, guilty?’ ‘Eh?’

‘I asked if he was guilty.’

‘In the eschatological sense?’ Flutek shot him a nasty look. ‘The Final Judgement and all? If so, I can only refer to the Nicene Credo: Jesus, crucified by Pontius Pilate, died, but rose and will come in glory again to judge the quick and the dead. Everyone shall be judged for their thoughts and deeds. And then it shall be established once and for all who was guilty.’

Reynevan sighed and shook his head. He only had himself to blame. He knew Flutek. He shouldn’t have asked.

‘Thus, it doesn’t matter who he was,’ said Flutek, nodding towards the beam and the severed rope. ‘What matters is that he managed to hang himself while we were breaking the door down. That I didn’t manage to force him to speak. And that you didn’t identify him. You claim it wasn’t him – not the man you allegedly eavesdropped on when he was plotting with the Bishop of Wroclaw in Silesia – is that true?’

‘It is.’

Flutek cast him a hideous glance. Flutek’s eyes, as black as a marten’s and which pointed down his long nose like the open ings of two gun barrels, were capable of looking extremely hid eous. At times, two tiny golden devils would appear in Flutek’s eyes which suddenly turned somersaults in unison. Reynevan had seen them before. And they usually heralded something very unpleasant.

‘But I think it isn’t,’ said Flutek. ‘I think you’re lying. And have been from the start, Reynevan.’

No one knew how Flutek had ended up working for Zizka. Rumours had circulated, naturally. According to some people, Bohuchval Neplach- real name Yehoram ben Yitzchak-was a Jew, a pupil of a rabbinical school, whom, on a whim, the Hus sites had spared during the massacre of the ghetto in Chomutov in March 1421. According to others, he wasn’t called Bohuchval but Gottlob and was a German, a merchant from Plzen. Still others said he was a monk, a Dominican, whom Zizka – for unknown reasons – had personally rescued from the massacre of priests and monks in Beroun. Other people claimed that Flutek had been a parish priest in Caslav, who joined the Hussites just in time and whose neophyte zeal had helped him ingratiate himself so effectively with Zizka that he landed himself a per manent post. Reynevan was in fact inclined to believe the last rumour. Flutek must have been a priest; his outrageous hypoc risy, duplicity, dreadful egoism and almost unimaginable greed spoke in favour of it.

It was indeed to his greed that Bohuchval Neplach owed his nickname. In 1419, Catholic noblemen captured Kutna Hora, the most important centre for extracting ore in Bohemia. Cut off from the mines and mints in Kutna Hora, Hussite Prague began striking its own coin, pennies with such low silver content that were practically worthless. Consequently, the Prague coins were scorned and contemptuously nicknamed ‘fl.uteks’. Thus, when Bohuchval Neplach began to serve as the head of Zizka’s intelligence, the nickname ‘Flutek’ stuck to him in a fl.ash, for it soon turned out that Bohuchval Neplach was prepared to do anything for even a single fl.utek – even stooping to pluck one from a pile of shit. Bohuchval Neplach never, ever passed up a chance to steal or embezzle one.

How Flutek managed to keep his position with Zizka, who harshly punished embezzlers in his New Tabor and fought thievery with an iron fist, was a mystery. And why Flutek was later tolerated by the no less principled Prokop the Shaven was also a mystery. Only one explanation was possible: Bohuchval Neplach was an expert at what he did for the Tabor. And experts can be forgiven a great deal. Shouldbe forgiven. For experts are rare and hard to come by.

‘If you want to know,’ Flutek continued, ‘I have had extremely little confidence in your tale, as indeed I have had in you, from the very beginning. Clandestine meetings, secret counsels and international conspiracies are all very well in literature and suit someone like, let’s say, Wolfram of Eschenbach. It’s pleasant to read Wolfram’s stories of mysteries and conspiracies … about the mystery of the Holy Grail, Terre de Salvaesche and all sorts of Klinschors, Flagetanises, Feirefizes and Titurels. There was just a bit too much of that literature in your account. In other words, I suspect you were simply lying.’

Reynevan said nothing, just shrugged. Qyite ostentatiously. ‘There can be various reasons for your confabulations,’ continued Flutek. ‘You fled Silesia, you claim, because you were persecuted, threatened with death. If it’s true, you didn’t have any other choice than to curry favour with Ambroz. And how more effectively than to warn him about an attempt on his life? Then you were brought before Prokop. Prokop usually suspects fugitives from Silesia of being spies, so he hangs the lot of them and per saldo comes out on top. So, how to save one’s skin? Why, for example, by making revelations about a secret counsel and a conspiracy. What do you say, Reynevan? How does it sound?’

‘Wolfram of Eschenbach would envy you.And you’d be bound to win the tournament in Wartburg.’

‘So you had enough reasons to confabulate,’ continued Flutek imperturbably. ‘But I think there was really just one.’

‘Of course,’ said Reynevan, knowing full well what he was getting at. ‘Just one.’

The two golden imps appeared in Flutek’s eyes. ‘The most ap pealing hypothesis to me is that your chicanery is designed to distract attention from the matter of greatest import. Namely, the five hundred grzywna stolen from the tax collector. What say you, physician?’

‘The same as usual.’ Reynevan yawned. ‘We’ve been through all this. I’ll respond in an unoriginal, boring way to your unoriginal, boring question. No, Brother Neplach, I won’t share the money stolen from the tax collector for several reasons. Firstly, I don’t have the money, because I wasn’t the one who stole it. Secondly-‘

‘So who stole it?’

‘To be boring: I have no idea.’

The two golden imps leaped up and turned a lissom somersault. ‘You’re lying.’

‘Naturally. May I go now?’

‘I have proof that you’re lying.’ ‘Oho.’

‘You claim,’ said Flutek, his eyes drilling through Reynevan, ‘that your imagined moot occurred on the thirteenth of Sep tember and that Kaspar Schlick took part in it. But I know from first-rate sources that Kaspar Schlick was in Buda on the thir teenth of September 1425. Thus, he couldn’t have been in Silesia.’ ‘You have third-rate sources, Neplach. Wait a moment, it’s an entrapment. You’re trying to trick me, ensnare me, and not for the first time – am I right?’

‘You are.’ Flutek did not bat an eyelid. ‘Sit down, Reynevan. I haven’t finished with you yet.’

‘I don’t have the money and I don’t know-‘

‘Be quiet.’

They said nothing for some time. The imps in Flutek’s eyes calmed down, almost vanished. But Reynevan wasn’t deceived. Flutek scratched his nose.

‘But for Prokop .. .’he said softly. ‘But for the fact that Prokop has forbidden me from laying a finger on you, you and that Scharley of yours, I’d have got what I wanted out of you already. With me, everybody finally talks; not one person has ever stayed silent. You, too, be certain, would tell me where the cash is.’

Reynevan was more experienced now and wasn’t to be frightened. He shrugged.

‘Yeees,’ Flutek continued after another break, looking at the rope hanging from the ceiling. ‘And this one would also have talked. I’d have wrung a testimony out of him, too. It’s a real pity he managed to hang himself Know what? For a moment, I really thought he might have been in that grange … You really disappointed me by not recognising him .. .’

‘I constantly disappoint you. It sorrows me greatly.’ The imps jumped slightly.

‘Really?’

‘Really. You suspect me, order me tailed, lie in wait for me, provoke me. You question my motives and constantly forget about the single, most important one: the Czech who was plot ting in the grange betrayed my brother, turned him over to die at the hands of the Bishop of Wrodaw’s executioners and even bragged about it to the bishop. So, had it been him hanging from that beam, I wouldn’t have skimped a farthing on a thanksgiving Mass. Believe me, I also regret it’s not him. Nor any of the others whom you’ve shown me at other times or asked me to identify.’

‘True,’ admitted Flutek, in a – probably feigned – reverie. ‘I once had my money on Divis Borek of Miletinek. My other tip was Hynek of Kolstejn … But neither of them-‘

‘Are you asking or stating? Because I’ve told you a hundred times it wasn’t either of them.’

‘Yes, after all, you had a good look at both of them … When I took you along with me-‘

‘At the Battle of Usti? I remember.’

* * *

The entire gentle slope was covered with bodies, but the most macabre site was by the River Zdiinice which ran along the bottom of the valley. There, partly stuck in the bloody mud, tow ered a mountain of bodies, human corpses mingled with those of horses. It was obvious what had happened. The boggy banks had prevented the men from Saxony and Meissen from fleeing, prevented them long enough for them to be caught first by the Taborite cavalry, and a moment later by the howling horde of infantry rushing after them. The mounted Czechs, Poles and Moravians didn’t waste much time and hacked to death anyone in their way, then swiftly set off in pursuit of the knighthood fleeing towards the town ofUsti. Meanwhile, the Hussite infan try- Taborites and Orphans – remained longer by the river. They slaughtered every last German. Systematically, keeping order, they surrounded and crowded them together, then flails, morn ing stars, clubs, halberds, gisarmes, voulges, bardiches, spears and pitchforks went into action. They gave no quarter. These Warriors of God, covered from head to foot in blood, shouting and singing as they returned from the battle, were leading no captives.

On the other bank of the Zdiznice, in the region of the Usti road, the cavalry and infantry still had their hands full.The clang ing of iron, roaring and yelling could be heard among clouds of dust as black smoke floated over the ground. Predlice and Hrbovice, hamlets on the far bank, were in flames, and judging from the sounds, a massacre was taking place there, too.

Horses snorted, twisted their heads, flattened their ears, shifted uneasily and stamped. The heat was unbearable.

Riders thundered towards them, raising dust, among them Rohac of Dube, Wyszek Raczynski and Jan Bleh ofTesnice and Puchala.

‘It’s almost over.’ Rohac hawked, spat and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. ‘There were some thirteen thousand of them. According to initial estimates, we’ve dealt with about three and a half thousand so far, but the work’s not over yet. The Saxons’ horses are weary, so they won’t get away – we’ll add some more to the reckoning. I’d say we’ll be putting up to four thousand to the sword.’

‘It may not be Grunwald,’ said Dobko Puchala with an un pleasant grin. The Wieniawa crest on his shield was almost indiscernible under a layer of bloody mud. ‘It may not be Grun wald, but it’s still beautiful. What, Your Grace?’

‘M’Lord Prokop.’ Sigismund Korybut appeared not to have heard him. ‘Isn’t it time to remember Christian mercy?’

Prokop the Shaven didn’t answer. He rode downhill, to the Zdiznice. Among the bodies.

‘Mercy’s one thing,’ said Jakubek of Vresovic, Hejtman of Bilina, angrily, riding a little to the rear, ‘but money’s another! Why, it’s simply a waste! Look at that one without a head – the crossed gold pitchforks on his shield mean he’s a Kalkreuth. A ransom of at least six thousand pre-revolutionary groschen. That one with his guts hanging out, with a pruning knife in a field divided diagonally on his shield, is a Dietrichstein. An eminent family, at least eighteen thousand … ‘

Right by the river, the Orphans stripping the corpses pulled a still-living youngster in armour and a tunic with a coat of arms from under a pile of bodies. The youngster dropped to his knees, put his hands together and begged. Then began to scream, was hit with a battleaxe and stopped.

‘Sable, a fess bretesse argent,’ Jakubek of Vresovic observed unemotionally, an expert in heraldry and economics both, ap parently. ‘So he’s a Nesselrode. Of the Nesselrode counts. About thirty thousand for the whippersnapper. We’re wasting money here, Brother Prokop.’

Prokop the Shaven turned his peasant’s face towards him. ‘God is our judge,’ he said hoarsely. ‘The men lying here didn’t have His seal on their brows. Their names weren’t in the Book of the Living.’

After a pregnant silence, he added, ‘In any case, no one asked them to come here.’

‘Neplach?’

‘What?’

‘You keep ordering me to spy, yet your thugs are still following me. Will you continue to have me spied on?’

‘Why do you ask?’

‘I can’t see the po·mt-‘

‘Reynevan. Do I teach you how to apply leeches?’

They said nothing for a while. Flutek kept looking back at the severed rope hanging from the beam.

‘Rats leaving a sinking ship,’ he said pensively. ‘Not only in Silesia do rats conspire in granges and castles, look for foreign protection and kiss the arses of bishops and herzogs. Because their ship is sinking, because they’re shitting themselves, be cause it’s the end of false hopes. Because we’re on the rise and they’re falling, all the way down to the shithouse! Korybut took a tumble, there was a pogrom and a massacre at -0sti, the Austrians were beaten hands down and slaughtered at Zwettl, Lusatia is aflame right back to Zgorzelec. Uhersky Brod and Pressburg are terrified, Olomouc and Trnava tremble behind Prokop is victorious-‘

‘For the time being.’ ‘What do you mean?’

‘At the Battle of Stribro … Rumour has it-‘

‘I know what the rumours say.’

‘A crusade is marching on us.’

‘Nothing new.’

‘The whole of Europe, they say-‘

‘Not all of it.’

‘Eighty thousand armed men-‘

‘Bullshit. Thirty, at most.’

‘But they’re saying-‘

‘Reynevan,’ Flutek calmly interrupted. ‘Think about it. Do you think if things were so dangerous, I’d still be here?’

They said nothing for a while.

‘As a matter of fact, any moment now things will become clearer,’ said the head of Taborite intelligence. ‘Any moment . You’ll hear.’

‘What? How? Who from?’

Flutek quietened him with a gesture and pointed at the window, then signalled for him to listen carefully. The bells of Prague were speaking.

The New Town began. The Virgin Mary at Travnicek was first, followed soon after by the Emmaus Monastery, a moment later by the bells of Saint Wenceslas’s Church at Zderaz, joined by Saint Stephen’s, then Saint Adalbert’s and Saint Michael’s, and after them the melodious bells of Our Lady of the Snows. A moment later, the bells of the Old Town began to sound, first Saint Giles’, then Saint Gall’s and finally the Church of Our Lady before Tyn. Then the bell towers of Hradcany: Saint Benedict’s, Saint George’s and All Saints’. Finally, the cathedral bell sounded; the most dignified, the deepest, the most brazen, spreading over the city.

The bells of Golden Prague were singing.

* * *

There was a terrible confusion and crush in the Old Town Square. People were teeming outside the town hall, pressed up against the gates as the bells tolled on. Caught in the pande monium, people were pushing each other, shouting over each other, waving their arms; all you could see were sweaty faces flushed with effort and excitement, open mouths and feverish eyes.

‘What’s happening?’ Reynevan caught a tanner stinking of tanning pickle by the sleeve. ‘News? Any news?’

‘Brother Prokop defeated the crusaders! At Tachov! He beat them hands down, crushed them!’

‘Was there a regular battle?’

‘Battle?’ shouted a character who had clearly just run from a barber, face still half-covered in foam. ‘Battle? They fled! The papists ran! For their lives! In panic!’

‘They left everything!’ bellowed an impassioned apprentice. ‘Weapons, cannons, goods, provisions! And fled! From the Battle ofTachov! Brother Prokop victorious! The Chalice victorious!’

‘What are you saying? Fled? Without joining battle?’

‘Aye, aye! And cut to ribbons by our boys as they ran!Tachov is encircled, the lords of the Landfried surrounded in their castle! Brother Prokop is belabouring the walls with bombards – it’ll soon fall! Brother Jakubek of Vresovic is harrying and routing Sir Heinrich of Plauen!’

‘Qµiet! Qµiet, all of you! Brother Jan is coming!’ ‘Brother Jan! Brother Jan! And the councillors!’

The town hall doors opened and a group of men came out onto the steps.

They were led by Jan Rokycana, parish priest of Our Lady before Tyn, short, with a noble, if not to say otherworldly, look. And quite young. The principal ideologist of the Utraquist revo lution at that time was thirty-five, ten years older than Reynevan. Walking beside his now-celebrated pupil and gasping for breath was Jacob of Stribro, university master. Half a step behind walked Peter Payne, an Englishman with the face of an ascetic. Then came the Old Town councillors: the powerfully built Jan Velvar, Matej Smolar, Vaclav Hedvika and others.

Rokycana stopped. ‘Brother Czechs!’ he cried, raising both hands. ‘People of Prague! God is with us! And God is above us!’

The roar of the crowd first intensified, then subsided and quietened down. The church bells stopped ringing in turn.

Rokycana didn’t lower his hands. ‘The heretics are vanquished!’ he cried even louder. ‘They who desecrated the Holy Cross by placing it – at Rome’s instigation – on their contemptible armour! They have been punished by God! Brother Prokop is victorious!’

The crowd roared in unison and cheered. The preacher hushed them.

‘Though the hellish hordes gathered here,’ he continued, ‘though the bloody talons of Babylon were stretching out to wards us, though once again the wrath of the Roman Antichrist threatened the true religion, God is above us! The Lord of the Heavens raised His hand to annihilate the enemy host! The same Lord who drowned Pharaoh’s army in the Red Sea, who forced the innumerable army of the Midianites to flee from Gideon. The Lord, who during the course of a single night employed His angel to defeat a hundred and eighty-five thousand Assyrians – that same Lord of the Heavens struck fear into the hearts of our foes! As the army of the blasphemer Sennacherib fled from Jerusalem, so the terrified papist rabble fled in panic from the Battles of Stribro and Tachov!’

‘As soon as the devilish servants saw the Chalice on Brother Prokop’s pennants,’ chimed in Jacob in a high voice, ‘when they heard the singing of the Warriors of God, they bolted in panic to the four points of the compass! They were as chaff scattered on the wind!’

‘Deus vicit!’ yelled Peter Payne. ‘Veritas vincit!’ ‘Te Deum laudamus!’

The crowd roared and howled. It was so loud, Reynevan’s ears hurt.

* * *

That evening, the fourth of August 1427, Prague thunderously and splendidly celebrated the victory. Praguians reacted to the weeks of fear and uncertainty with spontaneous festivities. They sang in the streets, danced around fires in squares, made merry in gardens and courtyards. The more pious celebrated Prokop’s victory at impromptu Masses, said in all of Prague’s churches. The less pious had a choice of a great variety of other forms of merriment. Everywhere, in the Old and New Towns, in the Lesser G.!iarter, which was still largely ashes, in Hradcany, almost everywhere, innkeepers celebrated the triumph over the crusade by treating anyone who wanted it to free alcohol and food. Throughout Prague, bungs and corks popped out of barrels and fragrant smells of cooking drifted from gridirons, spits and cauldrons. As usual, the crafty innkeepers took advantage of the situation – under cover of generosity- to rid themselves of stock that was in danger of going off and any that had spoiled long before. But who cared! The crusade was vanquished! The danger had passed! Let’s make merry!

People made merry the length and breadth of Prague. Toasts were drunk in honour of the doughty Prokop the Shaven and the Warriors of God, wishing confusion on the crusaders who had fled from Tachov. In particular, it was hoped that the leader of the crusade, Otto of Ziegenhain, the Archbishop ofTrier, would croak on the way home or at least fall ill. Hastily composed cou plets were sung telling how the papal legate Henry of Beaufort soiled his britches at the sight of Prokop’s banners.

Reynevan joined in the celebrations in the Old Town Square, then moved on to the Bear Inn in Perstyn near the Church of Saint Martin in the Wall with a large crowd of revelling strangers. Then the merry fraternity travelled to the New Town. Gathering up a few drunks on the way from the cemetery of Our Lady of the Snows, they headed for the Horse Market.There they visited in turn two taverns: the White Mare and Mejzlik’s.

Reynevan trailed faithfully after the company. Genuinely delighted by the victory at Tachov, he felt like celebrating and having fun and was worrying less about Scharley. The route suited him, for he lived in the New Town. But he abandoned the plan to go to the apothecary shop in the House at the Archangel in Soukenicka Street where he expected to meet Samson Hon eypot. He feared compromising the secret location and exposing the Czech alchemists and mages to being unmasked. And even worse. And there was a risk. He briefly glimpsed the grey shape, grey hood and grey face of an agent several times in the merry crowd at the White Mare. Flutek, it turned out, never gave up.

So, Reynevan made merry, but sparingly, and didn’t drink too much, although the magical decocts he had taken in Soukenicka Street made him resistant to all kinds of toxins, including alcohol. Finally, however, he decided to leave the party. The merrymak ing at Mejzlik’s was beginning to enter the stage that Scharley called: ‘Wine, vomit and song.’ ‘Women’ had intentionally been left out of the set.

Reynevan went out into the street and took a deep breath. Prague was quietening down. The sounds of the noisy revelling were slowly being drowned out by the choirs of frogs along the Vltava and the crickets in monastery gardens.

He walked towards the Horse Gate. As he passed taverns and beer cellars, his senses were assaulted by sour smells and the clinking of dishes, girlish squeals, shouts now a little drowsy and increasingly listless singing.

I’m a butcher, you’re a butcher, we’re both butchers

We’ll go off looking/or heifers

I’ll be buying, you’ll be haggling

We’ll court pretty maidens

A breeze was blowing, bearing the scent of flowers, leaves, sludge, smoke and God knows what else.

And blood.

Prague still reeked of blood. Reynevan was still being tor mented by that stench, still had it in his nostrils. He felt the anx iety it triggered in him. There were fewer and fewer passers-by and no sight or sound of Flutek’s spies, but the anxiety didn’t diminish.

He turned into Stara Pasffska Street, then into a lane called V Jame. As he walked, he was thinking about Nicolette, Katarzyna Biberstein. He thought about her incessantly and quickly expe rienced the effects of that thinking. The images appeared before his eyes so vividly and realistically, in such detail, that at a certain moment it all became unbearable – Reynevan stopped involun tarily and looked back. Involuntarily, because he knew there was nowhere to go anyway. Back in August 1419, barely twenty days after the Defenestration, every last brothel in Prague had been torn down and every last woman of easy virtue driven from the city. The Hussites were very strict regarding the observation of morality.

The realistic and detailed images of Katarzyna also triggered other associations. The rooms in the house at the corner of Saint Stephen’s Street and Na Rybnicku Street that Reynevan shared with Samson Honeypot had a landlady, Mistress Blazena Pospichalova, a widow rich in womanly charms with kind, blue eyes. Those eyes had come to rest on Reynevan in such an eloquent way that he suspected in Mistress Blazena desires that Scharley usually described punctiliously as a ‘union based only on lust and not the result of a Church-sanctioned alliance’. The rest of the world defined the activity much more concisely and bluntly. And the Hussites treated such bluntly defined activity with great severity. They usually did it for effect, admittedly, but no one ever knew who or what they might make an example of. So even though Reynevan understood Mistress Blazena’s glances, he pretended he didn’t. Partly out of fear of getting into hot water and partly – and even more so – out of a desire to remain faithful to his beloved Nicolette.

A furious caterwauling shook him out of his reverie as a large ginger cat dashed out of the dark alley on his right and ran off down the street. Reynevan immediately speeded up. It might have been Flutek’s spies who had scared the cat. But it might also have been common cutpurses lying in wait for a lonely passer-by. Dusk was falling, there was almost no one around, and when the backstreets of the New Town were dark and des erted, they stopped being safe. Particularly now, when most of the castle guard had joined Prokop’s army, it wasn’t advisable to roam around the New Town alone.

So Reynevan decided not to be alone. Two locals were walk ing about a dozen paces ahead of him. He had to make quite an effort to catch them up as they were walking fast and on hearing his footsteps had clearly speeded up. And suddenly turned into a backstreet. He followed them.

‘I say, brothers! Fear not! I only wanted to-‘

The men turned around. One had a suppurating chancre just beside his nose and a butcher’s knife in his hand. The other – shorter and thickset – was armed with a cleaver with a curved cross guard. Neither of them was Flutek’s spy.

The third one, who’d been following him and had scared the cat, had greyish hair and wasn’t the spy, either. He was carrying a dagger, slender and razor-sharp.

Reynevan stepped back, pressing himself against the wall. He held out his doctor’s bag towards the thugs.

‘Gentlemen … ‘ he gibbered, teeth chattering. ‘Brothers … Take it … It’s all I have … I … I beg … I beg you … Don’t kill me …

The thugs’ faces, at first hard and set, relaxed and melted into contemptuous grimaces. Scornful cruelty appeared in their previously cold and vigilant eyes. They advanced, raising their weapons, towards an easy and abject victim.

And Reynevan moved to the next phase. After the psycholog ical ruse a la Scharley, it was time to use other methods learned from other teachers.

The first character wasn’t expecting either an attack or that the medical satchel would be slammed straight into his festering nose. A kick to the shins made the second one stagger. The third, the thickset one, was astonished to find his cleaver slicing air and he himself tumbling onto a pile of rubbish, having tripped over a dexterously positioned foot. Seeing the others coming for him, Reynevan dropped the satchel and swiftly drew a dagger from his belt. He ducked under a knife-thrust and twisted the knife man’s wrist and elbow, exactly as explained in Hans Talhoffer’s Das Fechtbuch. He shoved one opponent into another, dodged and attacked from the side using a feint recommended for such situations in Chapter One of the volume devoted to knife fight ing in Fiore of Cividale’s Flos Duellatorum. When the thug in stinctively parried high, Reynevan stabbed him in the thigh, as instructed in the second chapter of the same manual. The thug howled and dropped to his knee. Reynevan dodged, kicked the assailant getting up from the rubbish heap as he passed, side stepped another thrust and pretended to stumble and lose his balance. The grey-haired thug with the dagger had clearly not read the classics or heard of feints, because he made a sudden, uncontrolled lunge, thrusting at Reynevan like a heron jabbing with its beak. Reynevan calmly knocked his arm up, twisted his wrist, caught him by the shoulder as recommended in Das Fecht buch and shoved him against the wall. The thug, trying to free himself, swung a violent left hook – which landed straight on the point of the dagger, positioned according to the instructions m Flos Duellatorum. The slender blade penetrated deep and Reynevan heard the crunch of severed metacarpals. The thug gave a piercing scream and dropped to his knees, pressing his hand, squirting blood, to his belly.

The third assailant, the thickset one, was on him quickly and slashed diagonally with the cleaver from left to right, very men acingly. Reynevan jumped back, parrying and dodging, expecting a textbook stance or position. But neither Meister Talhoffer nor messer Cividale were much use to him that day. Suddenly, some thing very grey, dressed in a grey hood, grey jerkin and grey hose, appeared behind the thug with the cleaver. A truncheon turned from pale wood whistled and a dull thud announced its powerful contact with the back of his head. The grey man was extremely fast. He managed to land another blow before the thug fell.

Flutek and several agents entered the backstreet.

‘Well?’ he asked. ‘Still think there’s no reason to keep tailing you?’

Reynevan was breathing heavily, gasping for breath through his open mouth. The terror had only just kicked in and his vision went so dark he had to lean against a wall.

Flutek came closer and bent over to examine the thug with the lacerated hand. He mimicked with swift movements the German block and Italian counter-blow used by Reynevan.

‘Well, well.’ He shook his head in approval and disbelief at the same time. ‘Skilfully done. Who would have thought you’d attain such dexterity? I knew you were taking lessons from a swordsman, but as he has two daughters, I thought you were training with one of them. Or both.’

Flutek gestured for the sobbing and bleeding thug to be bound. He looked around for the one who’d been stabbed in the thigh, but he had furtively slipped away. He ordered the one struck by the truncheon to be stood up. He was still dazed and dribbling. He couldn’t look straight ahead – his eyes were still crossing and uncrossing and kept rolling back into his head.

‘Who hired you?’

The thug’s eyes darted around at random and he tried to spit. Unsuccessfully. Flutek gestured and the thug was hit in the kidneys. When he inhaled with a hiss, he was hit again. Flutek waved a careless hand, indicating that the thug should be taken away.

‘You’ll speak,’ he promised as they marched him down the street. ‘You’ll tell us everything. No prisoner of mine has ever remained silent.’ Flutek turned around to Reynevan, who was still leaning against the wall. ‘To ask whether you have any sus picions would be to insult your intelligence. So I shall. Any idea who was behind this?’

Reynevan nodded. Flutek also nodded, in approval.

‘The thugs will speak. Everyone talks in the end. Even Martin Loquis finally spoke, and he was a tough and determined little bugger, an idealist and true martyr to the cause. Scoundrels hired for a few pre-revolutionary pence will sing at the very sight of the tools. But I’ll still treat them to the red-hot iron. Out of pure affection for you, their would-be victim. Don’t thank me.’

Reynevan didn’t.

‘Out of pure affection,’ continued Flutek, ‘I’ll do something else for you. I’ll let you avenge your brother personally, with your own hand. Yes, yes, you heard right. Don’t thank me.’ Reynevan didn’t thank him that time, either. As a matter of fact, Flutek’s words hadn’t sunk in yet. ‘In a short while, my man will report to you. He will instruct you to go to the House of the Golden Horse in the town square, where we spoke today. Go there forthwith. And take a crossbow with you. Have you got that? Good. Farewell.’

‘Farewell, Neplach.’

* * *

There were no further incidents.It was dark by the time Reynevan reached the corner of Saint Stephen’s and Na Rybnicku Streets and the house with the room on the first floor that he and Samson Honeypot rented from Mistress Blazena Pospichalova, the thirty-year-old widow of Master Pospichal, requiescat in pace, may God bless him and keep him, whoever he was, what he did, how he lived and whatever he died 0£

He gingerly opened the garden gate and entered the pitch dark hall. He tried his best to keep the door from squeaking and the old wooden stairs from creaking. He always did when he re turned after dark. He didn’t want to meet Mistress Blazena. He somewhat feared what a confrontation with Mistress Blazena after dark might lead to.

In spite of his efforts, a step creaked. The door opened and he

smelled Hungary water, rouge, wine, wax, plum jam, old wood and freshly laundered bed linen. Reynevan felt a plump arm around his neck and a pair of plump breasts pressing him against the banisters.

‘We’re celebrating tonight,’ Mistress Blazena Pospichalova whispered into his ear. ‘It’s a holiday today, my boy.’

‘Mistress Blazena … But … Should one-‘ ‘Be quiet. Come.’

‘But-‘

‘Qyiet.’

‘I love another!’

The widow pulled him into her chamber and pushed him onto the bed. He plunged into the abyss of the starch-smelling feather bed and sank into it, overpowered by the downy softness.

‘I … love … another …’

‘No one’s stopping you, deary.’

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...