- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

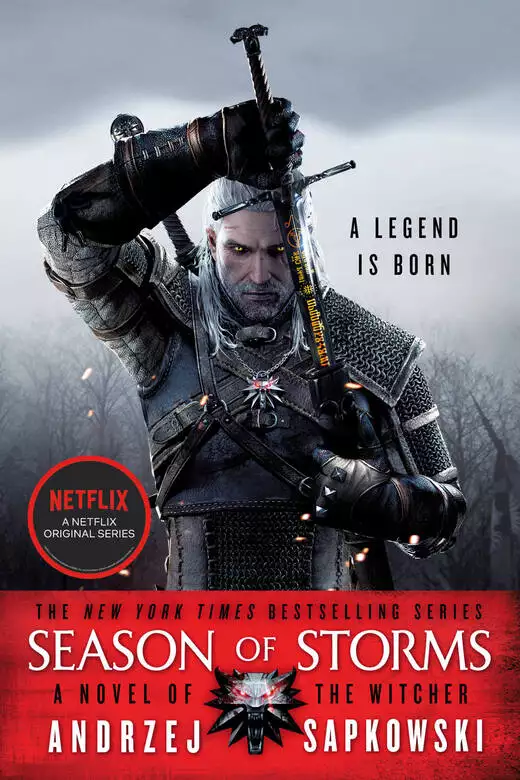

Enter the world of The Witcher by Andrzej Sapkowski, New York Times bestselling author and winner of the world fantasy award for lifetime achievement.

Geralt of Rivia is a Witcher, one of the few capable of hunting the monsters that prey on humanity. A mutant who is tasked with killing unnatural beings. He uses magical signs, potions, and the pride of every Witcher—two swords, steel and silver.

But a contract has gone wrong, and Geralt finds himself without his signature weapons. Now he needs them back, because sorcerers are scheming, and across the world clouds are gathering.

The season of storms is coming…

Witcher novels

Blood of Elves

The Time of Contempt

Baptism of Fire

The Tower of Swallows

Lady of the Lake

Witcher collections

The Last Wish

Sword of Destiny

Translated from original Polish by David French

Release date: May 22, 2018

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 432

Reader says this book is...: action-packed (1) entertaining story (1) epic storytelling (1) great world-building (1) high adventure (1) suspenseful (1)

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Season of Storms

Andrzej Sapkowski

It was lying on the sun-warmed sand.

It could sense the vibrations being transmitted through its hair-like feelers and bristles. Though the vibrations were still far off, the idr could feel them distinctly and precisely; it was thus able to determine not only its quarry’s direction and speed of movement, but also its weight. As with most similar predators, the weight of the prey was of cardinal importance. Stalking, attacking and giving chase meant a loss of energy that had to be compensated by the calorific value of its food. Most predators similar to the idr would quit their attack if their prey was too small. But not the idr. The idr didn’t exist to eat and sustain the species. It hadn’t been created for that.

It lived to kill.

Moving its limbs cautiously, it exited the hollow, crawled over a rotten tree trunk, covered the clearing in three bounds, plunged into the fern-covered undergrowth and melted into the thicket. It moved swiftly and noiselessly, now running, now leaping like a huge grasshopper.

It sank into the thicket and pressed the segmented carapace of its abdomen to the ground. The vibrations in the ground became more and more distinct. The impulses from the idr’s feelers and bristles formed themselves into an image. Into a plan. The idr now knew where to approach its victim from, where to cross its path, how to force it to flee, how to swoop on it from behind with a great leap, from what height to strike and lacerate with its razor-sharp mandibles. Within it the vibrations and impulses were already arousing the joy it would experience when its victim started struggling under its weight, arousing the euphoria that the taste of hot blood would induce in it. The ecstasy it would feel when the air was rent by a scream of pain. It trembled slightly, opening and closing its pincers and pedipalps.

The vibrations in the ground were very distinct and had also diversified. The idr now knew there was more than one victim—probably three, or perhaps four. Two of them were shaking the ground in a normal way; the vibrations of the third suggested a small mass and weight. The fourth, meanwhile—provided there really was a fourth—was causing irregular, weak and hesitant vibrations. The idr stopped moving, tensed and extended its antennae above the grass, examining the movements of the air.

The vibrations in the ground finally signalled what the idr had been waiting for. Its quarry had separated. One of them, the smallest, had fallen behind. And the fourth—the vague one—had disappeared. It had been a fake signal, a false echo. The idr ignored it.

The smallest target moved even further away from the others. The trembling in the ground was more intense. And closer. The idr braced its rear limbs, pushed off and leaped.

The little girl gave an ear-splitting scream. Rather than running away, she had frozen to the spot. And was screaming unremittingly.

The Witcher darted towards her, drawing his sword mid-leap. And realised at once that something was wrong. That he’d been tricked.

The man pulling a handcart loaded with faggots screamed and shot six feet up into the air in front of Geralt’s eyes, blood spraying copiously from him. He fell, only to immediately fly up again, this time in two pieces, each spurting blood. He’d stopped screaming. Now the woman was screaming piercingly and, like her daughter, was petrified and paralysed by fear.

Although he didn’t believe he would, the Witcher managed to save her. He leaped and pushed hard, throwing the blood-spattered woman from the path into the forest, among the ferns. And realised at once that this time, too, it had been a trick. A ruse. For the flat, grey, many-limbed and incredibly quick shape was now moving away from the handcart and its first victim. It was gliding towards the next one. Towards the still shrieking little girl. Geralt sped after the idr.

Had she remained where she was, he would have been too late. But the girl demonstrated presence of mind and bolted frantically. The grey monster, however, would easily have caught up with her, killed her and turned back to dispatch the woman, too. That’s what would have happened had it not been for the Witcher.

He caught up with the monster and jumped, pinning down one of its rear limbs with his heel. If he hadn’t jumped aside immediately he would have lost a leg—the grey creature twisted around with extraordinary agility, and its curved pincers snapped shut, missing him by a hair’s breadth. Before the Witcher could regain his balance the monster sprang from the ground and attacked. Geralt defended himself instinctively with a broad and rather haphazard swing of his sword that pushed the monster away. He hadn’t wounded it, but now he had the upper hand.

He sprang up and fell on the monster, slashing backhand, cleaving the carapace of the flat cephalothorax. Before the dazed creature came to its senses, a second blow hacked off its left mandible. The monster attacked, brandishing its limbs and trying to gore him with its remaining mandible like an aurochs. The Witcher hacked that one off too. He slashed one of the idr’s pedipalps with a swift reverse cut. Then hacked at the cephalothorax again.

It finally dawned on the idr that it was in danger. That it must flee. Flee far from there, take cover, find a hiding place. It only lived to kill. In order to kill it must regenerate. It must flee… Flee…

The Witcher didn’t let it. He caught up with it, stepped on the rear segment of the thorax and cut from above with a fierce blow. This time, the carapace gave way, and viscous, greenish fluid gushed and poured from the wound. The monster flailed around, its limbs thrashing the ground chaotically.

Geralt cut again with his sword, this time completely severing the flat head from the body.

He was breathing heavily.

It thundered in the distance. The growing wind and darkening sky heralded an approaching storm.

Right from their very first encounter, Albert Smulka, the newly appointed district reeve, reminded Geralt of a swede—he was stout, unwashed, thick-skinned and generally pretty dull. In other words, he didn’t differ much from all the other district clerks Geralt had dealt with.

“Would seem to be true,” said the reeve. “Nought like a witcher for dealing with troubles. Jonas, my predecessor, couldn’t speak highly enough of you,” he continued a moment later, not waiting for any reaction from Geralt. “To think, I considered him a liar. I mean that I didn’t completely lend credence to him. I know how things can grow into fairy tales. Particularly among the common folk, with them there’s always either a miracle or a marvel, or some witcher with superhuman powers. And here we are, turns out it’s the honest truth. Uncounted people have died in that forest beyond the little river. And because it’s a shortcut to the town the fools went that way… to their own doom. Heedless of warnings. These days it’s better not to loiter in badlands or wander through forests. Monsters and man-eaters everywhere. A dreadful thing has just happened in the Tukaj Hills of Temeria—a sylvan ghoul killed fifteen people in a charcoal-burners’ settlement. It’s called Rogovizna. You must have heard. Haven’t you? But it’s the truth, cross my heart and hope to die. It’s said even the wizardry have started an investigation in that there Rogovizna. Well, enough of stories. We’re safe here in Ansegis now. Thanks to you.”

He took a coffer from a chest of drawers, spread out a sheet of paper on the table and dipped a quill in an inkwell.

“You promised you’d kill the monster,” he said, without raising his head. “Seems you weren’t having me on. You’re a man of your word, for a vagabond… And you saved those people’s lives. That woman and the lass. Did they even thank you? Express their gratitude?”

No, they didn’t. The Witcher clenched his jaw. Because they haven’t yet fully regained consciousness. And I’ll be gone before they do. Before they realise I used them as bait, convinced in my conceited arrogance that I was capable of saving all three of them. I’ll be gone before it dawns on the girl, before she understands I’m to blame for her becoming a half-orphan.

He felt bad. No doubt because of the elixirs he’d taken before the fight. No doubt.

“That monster is a right abomination.” The reeve sprinkled some sand over the paper, and then shook it off onto the floor. “I had a look at the carcass when they brought it here… What on earth was it?”

Geralt wasn’t certain in that regard, but didn’t intend to reveal his ignorance.

“An arachnomorph.”

Albert Smulka moved his lips, vainly trying to repeat the word.

“Ugh, meks no difference, when all’s said and done. Did you dispatch it with that sword? With that blade? Can I take a look?”

“No, you can’t.”

“Ha, because it’s no doubt enchanted. And it must be dear… Quite something… Well, here we are jawing away and time’s passing. The task’s been executed, time for payment. But first the formalities. Make your mark on the bill. I mean, put a cross or some such.”

The Witcher took the bill from Smulka and held it up to the light.

“Look at ’im.” The reeve shook his head, grimacing. “What’s this, can he read?”

Geralt put the paper on the table and pushed it towards the official.

“A slight error has crept into the document,” he said, calmly and softly. “We agreed on fifty crowns. This bill has been made out for eighty.”

Albert Smulka clasped his hands together and rested his chin on them.

“It isn’t an error.” He also lowered his voice. “Rather, a token of gratitude. You killed the monster and I’m sure it was an exacting job… So the sum won’t astonish anyone…”

“I don’t understand.”

“Pull the other one. Don’t play the innocent. Trying to tell me that when Jonas was in charge he never made out bills like this? I swear I—”

“What do you swear?” Geralt interrupted. “That he inflated bills? And went halves with me on the sum the royal purse was deprived of?”

“Went halves?” the reeve sneered. “Don’t be soft, Witcher, don’t be soft. Reckon you’re that important? You’ll get a third of the difference. Ten crowns. It’s a decent bonus for you anyway. For I deserve more, if only owing to my function. State officials ought to be wealthy. The wealthier the official, the greater the prestige to the state. Besides, what would you know about it? This conversation’s beginning to weary me. You signing it or what?”

The rain hammered on the roof. It was pouring down outside. But the thunder had stopped; the storm had moved away.

Two days later

“Do come closer, madam.” Belohun, King of Kerack, beckoned imperiously. “Do come closer. Servants! A chair!”

The chamber’s vaulting was decorated with a plafond of a fresco depicting a sailing ship at sea, amidst mermen, hippocampi and lobster-like creatures. The fresco on one of the walls, however, was a map of the world. An absolutely fanciful map, as Coral had long before realised, having little in common with the actual locations of lands and seas, but pleasing and tasteful.

Two pages lugged in and set down a heavy, carved curule seat. The sorceress sat down, resting her hands on the armrests so that her ruby-encrusted bracelets would be very conspicuous and not escape the king’s attention. She had a small ruby tiara on her coiffed hair, and a ruby necklace in the plunging neckline of her dress. All especially for the royal audience. She wanted to make an impression. And had. King Belohun stared goggle-eyed: though it wasn’t clear whether at the rubies or the cleavage.

Belohun, son of Osmyk, was, it could be said, a first-generation king. His father had made quite a considerable fortune from maritime trade, and probably also a little from buccaneering. Having finished off the competition and monopolised the region’s cabotage, Osmyk named himself king. That act of self-anointed coronation had actually only formalised the status quo, and hence did not arouse significant quibbles nor provoke protests. Over the course of various private wars and skirmishes, Osmyk had smoothed over border disputes and jurisdictional squabbles with his neighbours, Verden and Cidaris. It was established where Kerack began, where it finished and who ruled there. And since he ruled, he was king—and deserved the title. By the natural order of things titles and power pass from father to son, so no one was surprised when Belohun ascended his father’s throne, following Osmyk’s death. Osmyk admittedly had more sons—at least four of them—but they had all renounced their rights to the crown, one of them allegedly even of his own free will. Thus, Belohun had reigned in Kerack for over twenty years, deriving profits from shipbuilding, freight, fishery and piracy in keeping with family traditions.

And now King Belohun, seated on a raised throne, wearing a sable calpac and with a sceptre in one hand, was granting an audience. As majestic as a dung beetle on a cowpat.

“Our dear Madam Lytta Neyd,” he greeted her. “Our favourite sorceress, Lytta Neyd. She has deigned to visit Kerack again. And surely for a long stay again?”

“The sea air’s good for me.” Coral crossed her legs provocatively, displaying a bootee with fashionable cork heels. “With the gracious permission of Your Royal Highness.”

The king glanced at his sons sitting beside him. Both were tall and slender, quite unlike their father, who was bony and sinewy, but of not very imposing height. Neither did they look like brothers. The older, Egmund, had raven-black hair, while Xander, who was a little younger, was almost albino blond. Both looked at Lytta with dislike. They were evidently annoyed by the privilege that permitted sorceresses to sit in the presence of kings, and that such seated audiences were granted to them. The privilege was well established, however, and could not be flouted by anyone wanting to be regarded as civilised. And Belohun’s sons very much wanted to be regarded as civilised.

“We graciously grant our permission,” Belohun said slowly. “With one proviso.”

Coral raised a hand and ostentatiously examined her fingernails. It was meant to signal that she couldn’t give a shit about Belohun’s proviso. The king didn’t decode the signal. Or if he did he concealed it skilfully.

“It has reached our ears,” he puffed angrily, “that the Honourable Madam Neyd makes magical concoctions available to womenfolk who don’t want children. And helps those who are already pregnant to abort the foetus. We, here in Kerack, consider such a practice immoral.”

“What a woman has a natural right to,” replied Coral, dryly, “cannot—ipso facto—be immoral.”

“A woman—” the king straightened up his skinny frame on the throne “—has the right to expect only two gifts from a man: a child in the summer and thin bast slippers in the winter. Both the former and the latter gifts are intended to keep the woman at home, since the home is the proper place for a woman—ascribed to her by nature. A woman with a swollen belly and offspring clinging to her frock will not stray from the home and no foolish ideas will occur to her, which guarantees her man peace of mind. A man with peace of mind can labour hard for the purpose of increasing the wealth and prosperity of his king. Neither do any foolish ideas occur to a man confident of his marriage while toiling by the sweat of his brow and with his nose to the grindstone. But if someone tells a woman she can have a child when she wants and when she doesn’t she mustn’t, and when to cap it all someone offers a method and passes her a physick, then, Honourable Lady, then the social order begins to totter.”

“That’s right,” interjected Prince Xander, who had been waiting for some time for a chance to interject. “Precisely!”

“A woman who is averse to motherhood,” continued Belohun, “a woman whose belly, the cradle and a host of brats don’t imprison her in the homestead, soon yields to carnal urges. The matter is, indeed, obvious and inevitable. Then a man loses his inner calm and balanced state of mind, something suddenly goes out of kilter and stinks in his former harmony, nay, it turns out that there is no harmony or order. In particular, there is none of the order that justifies the daily grind. And the truth is I appropriate the results of that hard work. And from such thoughts it’s but a single step to upheaval. To sedition, rebellion, revolt. Do you see, Neyd? Whoever gives womenfolk contraceptive agents or enables pregnancies to be terminated undermines the social order and incites riots and rebellion.”

“That is so,” interjected Xander. “Absolutely!”

Lytta didn’t care about Belohun’s outer trappings of authority and imperiousness. She knew perfectly well that as a sorceress she was immune and that all the king could do was talk. However, she refrained from bluntly bringing to his attention that things had been out of kilter and stinking in his kingdom for ages, that there was next to no order in it, and that the only “Harmony” known to his subjects was a harlot of the same name at the portside brothel. And mixing up in it women and motherhood—or aversion to motherhood—was evidence not only of misogyny, but also imbecility.

Instead of that she said the following: “In your lengthy disquisition you keep stubbornly returning to the themes of increasing wealth and prosperity. I understand you perfectly, since my own prosperity is also extremely dear to me. And not for all the world would I give up anything that prosperity provides me with. I judge that a woman has the right to have children when she wants and not to have them when she doesn’t, but I shall not enter into a debate in that regard; after all, everyone has the right to some opinion or other. I merely point out that I charge a fee for the medical help I give women. It’s quite a significant source of my income. We have a free market economy, Your Majesty. Please don’t interfere with the sources of my income. Because my income, as you well know, is also the income of the Chapter and the entire consorority. And the consorority reacts extremely badly to any attempts to diminish its income.”

“Are you trying to threaten me, Neyd?”

“The very thought! Not only am I not, but I declare my far-reaching help and collaboration. Know this, Belohun, that if—as a result of the exploitation and plunder you’re engaged in—unrest occurs in Kerack, if—speaking grandiloquently—the fire of rebellion flares up, or if a rebellious rabble comes to drag you out by the balls, dethrone you and hang you forthwith from a dry branch… Then you’ll be able to count on my consorority. And the sorcerers. We’ll come to your aid. We shan’t allow revolt or anarchy, because they don’t suit us either. So keep on exploiting and increasing your wealth. Feel free. And don’t interfere with others doing the same. That’s my request and advice.”

“Advice?” fumed Xander, rising from his seat. “You, advising? My father? My father is the king! Kings don’t listen to advice—kings command!”

“Sit down and be quiet, son.” Belohun grimaced, “And you, witch, listen carefully. I have something to say to you.”

“Yes?”

“I’m taking a new lady wife… Seventeen years old… A little cherry, I tell you. A cherry on a tart.”

“My congratulations.”

“I’m doing it for dynastic reasons. Out of concern for the succession and order in the land.”

Egmund, previously silent as the grave, jerked his head up.

“Succession?” he snarled, and the evil glint in his eyes didn’t escape Lytta’s notice. “What succession? You have six sons and eight daughters, including bastards! What more do you want?”

“You can see for yourself.” Belohun waved a bony hand. “You can see for yourself, Neyd. I have to look after the succession. Am I to leave the kingdom and the crown to someone who addresses his parent thus? Fortunately, I’m still alive and reigning. And I mean to reign for a long time. As I said, I’m wedding—”

“What of it?”

“Were she…” The king scratched behind an ear and glanced at Lytta from under half-closed eyelids. “Were she… I mean my new, young wife… to ask you for those physicks… I forbid you from giving them. Because I’m against physicks like that. Because they’re immoral!”

“We can agree on that.” Coral smiled charmingly. “If your little cherry asks I won’t give her anything. I promise.”

“I understand.” Belohun brightened up. “Why, how splendidly we’ve come to agreement. The crux is mutual understanding and respect. One must even differ with grace.”

“That’s right,” interjected Xander. Egmund bristled and swore under his breath.

“In the spirit of respect and understanding—” Coral twisted a ginger ringlet around a finger and looked up at the plafond “—and also out of concern for harmony and order in your country… I have some information. Confidential information. I consider informants repellent; but fraudsters and thieves even more so. And this concerns impudent embezzlement, Your Majesty. People are trying to rob you.”

Belohun leaned forward from his throne, grimacing like a wolf.

“Who? I want names!”

The bay bristled with masts and filled with sails, some white, some many-coloured. The larger ships stood at anchor, protected by a headland and a breakwater. In the port itself, smaller and absolutely tiny vessels were moored alongside wooden jetties. Almost all of the free space on the beach was occupied by boats. Or the remains of boats.

A white-and-red-brick lighthouse, originally built by the elves and later renovated, stood tall at the end of the headland where it was being buffeted by white breakers.

The Witcher spurred his mare in her sides. Roach raised her head and flared her nostrils as though also enjoying the smell of the sea breeze. Urged on, she set off across the dunes. Towards the city, now nearby.

The city of Kerack, the chief metropolis of the kingdom bearing the same name, was divided into three separate, distinct zones straddling both banks at the mouth of the River Adalatte.

The port complex with docks and an industrial and commercial centre, including a shipyard and workshops as well as food-processing plants, warehouses and stores was located on the left bank of the Adalatte.

The river’s right bank, an area called Palmyra, was occupied by the shacks and cottages of labourers and paupers, the houses and stalls of small traders, abattoirs and shambles, and numerous bars and dens that only livened up after nightfall, since Palmyra was also the district of entertainment and forbidden pleasures. It was also quite easy, as Geralt knew well, to lose one’s purse or get a knife in the ribs there.

Kerack proper, an area consisting of narrow streets running between the houses of wealthy merchants and financiers, manufactories, banks, pawnbrokers, shoemakers’ and tailors’ shops, and large and small stores, was situated further away from the sea, on the left bank, behind a high palisade of robust stakes. Located there were also taverns, coffee houses and inns of superior category, including establishments offering, indeed, much the same as the port quarter of Palmyra, but at considerably higher prices. The centre of the district was a quadrangular town square featuring the town hall, the theatre, the courthouse, the customs office and the houses of the city’s elite. A statue of the city’s founder, King Osmyk, dreadfully spattered in bird droppings, stood on a plinth in the middle of the town square. It was a downright lie, as a seaside town had existed there long before Osmyk arrived from the devil knows where.

Higher up, on a hill, stood the castle and the royal palace, which were quite unusual in terms of form and shape. It had previously been a temple, which was abandoned by its priests embittered by the townspeople’s total lack of interest and then modified and extended. The temple’s campanile—or bell tower—and its bell had even survived, which the incumbent King Belohun ordered to be tolled every day at noon and—clearly just to spite his subjects—at midnight. The bell sounded as the Witcher began to ride between Palmyra’s cottages.

Palmyra stank of fish, laundry and cheap restaurants, and the crush in the streets was dreadful, which cost the Witcher a great deal of time and patience to negotiate the streets. He breathed a sigh when he finally arrived at the bridge and crossed onto the Adalatte’s left bank. The water smelled foul and bore scuds of dense foam—waste from the tannery located upstream. From that point it wasn’t far to the road leading to the palisaded city.

Geralt left his horse in the stables outside the city centre, paying for two days in advance and giving the stableman some baksheesh in order to ensure that Roach was adequately cared for. He headed towards the watchtower. One could only enter Kerack through the watchtower, after undergoing a search and the rather unpleasant procedures accompanying it. This necessity somewhat angered the Witcher, but he understood its purpose—the fancier townspeople weren’t especially overjoyed at the thought of visits by guests from dockside Palmyra, particularly in the form of mariners from foreign parts putting ashore there.

He entered the watchtower, a log building that he knew accommodated the guardhouse. He thought he knew what to expect. He was wrong.

He had visited numerous guardhouses in his life: small, medium and large, both nearby and in quite distant parts of the world, some in more and less civilised—and some quite uncivilised—regions. All the world’s guardhouses stank of mould, sweat, leather and urine, as well as iron and the grease used to preserve it. It was no different in the Kerack guardhouse. Or it wouldn’t have been, had the classic guardhouse smell not been drowned out by the heavy, choking, floor-to-ceiling odour of farts. There could be no doubt that leguminous plants—most likely peas and beans—prevailed in the diet of the guardhouse’s crew.

And the garrison was wholly female. It consisted of six women currently sitting at a table and busy with their midday meal. They were all greedily slurping some morsels floating in a thin paprika sauce from earthenware bowls.

The tallest guard, clearly the commandant, pushed her bowl away and stood up. Geralt, who always maintained there was no such thing as an ugly woman, suddenly felt compelled to revise this opinion.

“Weapons on the bench!”

The commandant’s head—like those of her comrades—was shaven. Her hair had managed to grow back a little, giving rise to patchy stubble on her bald head. The muscles of her midriff showed from beneath her unbuttoned waistcoat and gaping shirt, bringing to mind a netted pork roast. The guard’s biceps—to remain on the subject of cooked meat—were the size of hams.

“Put your weapons on the bench!” she repeated. “You deaf?”

One of her subordinates, still hunched over her bowl, raised herself a little and farted, loud and long. Her companions guffawed. Geralt fanned himself with a glove. The guard looked at his swords.

“Hey, girls! Get over here!”

The “girls” stood up rather reluctantly, stretching. Their style of clothing, Geralt noticed, was quite informal, mainly intended to show off their musculature. One of them was wearing leather shorts with the legs split at the seams to accommodate her thighs. Two belts crossing her chest were pretty much all she had on above the waist.

“A witcher,” she stated. “Two swords. Steel and silver.”

Another—like all of them, tall and broad-shouldered—approached, tugged open Geralt’s shirt unceremoniously and pulled out his medallion by the silver chain.

“He has a sign,” she stated. “There’s a wolf on it, fangs bared. Would seem to be a witcher. Do we let him through?”

“Rules don’t prohibit it. He’s handed over his swords…”

“That’s correct,” Geralt joined the conversation in a calm voice. “I have. They’ll both remain, I presume, in safe deposit? To be reclaimed on production of a docket. Which you’re about to give me?”

The guards surrounded him, grinning. One of them prodded him, apparently by accident. Another farted thunderously.

“That’s your receipt,” she snorted.

“A witcher! A hired monster killer! And he gave up his swords! At once! Meek as a schoolboy!”

“Bet he’d turn his cock over as well, if we ordered him to.”

“Let’s do it then! Eh, girls? Have him whip it out!”

“We’ll see what witchers’ cocks are like!”

“Here we go,” snapped the commandant. “They’re off now, the sluts. Gonschorek, get here! Gonschorek!”

A balding, elderly gentleman in a dun mantle and woollen beret emerged from the next room. Immediately he entered he had a coughing fit, took off his beret and began to fan himself with it. He took the swords wrapped in their belts and gestured for Geralt to follow him. The Witcher didn’t linger. Intestinal gases had definitely begun to predominate in the noxious mixture of the guardhouse.

The room they entered was split down the middle by a sturdy iron grating. The large key the elderly gentleman opened it with grated in the lock. He hung the swords on a hook beside other sabres, claymores, broadswords and cutlasses. He opened a scruffy register, scrawled slowly and lengthily in it, coughing incessantly and struggling to catch his breath. He finall

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...