- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

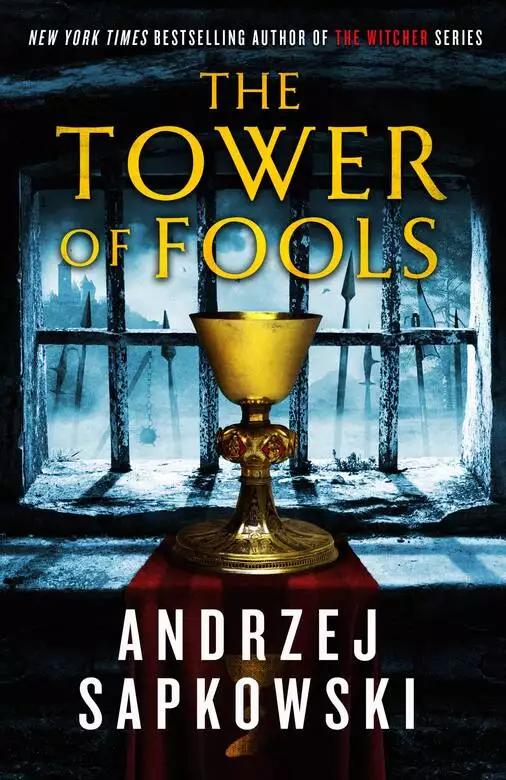

A BRAND NEW TRILOGY from the author of the legendary WITCHER series, set during the vibrantly depicted Hussite wars.

Reinmar of Bielau, called Reynevan, flees after being caught in an affair with a knight's wife.

With strange, mystical forces gathering in the shadows and pursued not only by the Stercza brothers bent on vengeance, but also by the Holy Inquisition, Reynevan finds himself in the Narrenturm, the Tower of Fools, a medieval asylum for the mad, or for those who dare to think differently and challenge the prevailing order.

The 'patients' of this institution form an incomparable gallery of colourful types: including, among others, the young Copernicus, proclaiming the truth of the heliocentric solar system.

This is the first in an epic new series from the phenomenon, ANDRZEJ SAPKOWSKI, author of the WITCHER books

Praise for Andrzej Sapkowski:

'Like Mieville and Gaiman, Sapkowski takes the old and makes it new' FOUNDATION

'Like a complicated magic spell, a Sapkowski novel is a hodge podge of fantasy, intellectual discourse and dry humour. Recommended' TIME

Release date: October 27, 2020

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 576

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Tower of Fools

Andrzej Sapkowski

Through the small chamber’s window, against a background of the recently stormy sky, could be seen three towers. The first belonged to the town hall. Further off, the slender spire of the Church of Saint John the Evangelist, its shiny red tiles glistening in the sun. And beyond that, the round tower of the ducal castle. Swifts winged around the church spire, frightened by the recent tolling of the bells, the ozone-rich air still shuddering from the sound.

The bells had also quite recently tolled in the towers of the Churches of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Corpus Christi. Those towers, however, weren’t visible from the window of the chamber in the garret of a wooden building affixed like a swallow’s nest to the complex of the Augustinian hospice and priory.

It was time for Sext. The monks began the Deus in adjutorium while Reinmar of Bielawa—known to his friends as “Reynevan”—kissed the sweat-covered collarbone of Adèle of Stercza, freed himself from her embrace and lay down beside her, panting, on bedclothes hot from lovemaking.

Outside, Priory Street echoed with shouts, the rattle of wagons, the dull thud of empty barrels and the melodious clanking of tin and copper pots. It was Wednesday, market day, which always attracted large numbers of merchants and customers.

Memento, salutis Auctor

quod nostri quondam corporis,

ex illibata Virgine

nascendo, formam sumpseris.

Maria mater gratiae,

mater misericordiae,

tu nos ab hoste protege,

et hora mortis suscipe…

They’re already singing the hymn, thought Reynevan, lazily embracing Adèle, a native of distant Burgundy and the wife of the knight Gelfrad of Stercza. The hymn has begun. It beggars belief how swiftly moments of happiness pass. One wishes they would last for ever, but they fade like a fleeting dream.

“Reynevan… Mon amour… My divine boy…” Adèle interrupted his dreamy reverie. She, too, was aware of the passing of time, but evidently had no intention of wasting it on philosophical deliberations.

Adèle was utterly, completely, totally naked.

Every country has its customs, thought Reynevan. How fascinating it is to learn about the world and its peoples. Silesian and German women, for example, when they get down to it, never allow their shifts to be lifted higher than their navels. Polish and Czech women gladly lift theirs themselves, above their breasts, but not for all the world would they remove them completely. But Burgundians, oh, they cast off everything at once, their hot blood apparently unable to bear any cloth on their skin during the throes of passion. Ah, what a joy it is to learn about the world. The countryside of Burgundy must be beautiful. Lofty mountains… Steep hillsides… Vales…

“Ah, aaah, mon amour,” moaned Adèle of Stercza, thrusting her entire Burgundian landscape against Reynevan’s hand.

Reynevan, incidentally, was twenty-three and quite lacking in worldly experience. He had known very few Czech women, even fewer Silesians and Germans, one Polish woman, one Romani, and had once been spurned by a Hungarian woman. Far from impressive, his erotic experiences were actually quite meagre in terms of both quantity and quality, but they still made him swell with pride and conceit. Reynevan—like every testosterone-fuelled young man—regarded himself as a great seducer and erotic connoisseur to whom the female race was an open book. The truth was that his eleven trysts with Adèle of Stercza had taught Reynevan more about the ars amandi than his three-year studies in Prague. Reynevan hadn’t understood, however, that Adèle was teaching him, certain that all that counted was his inborn talent.

Ad te levavi oculos meos

qui habitas in caelis.

Ecce sicut oculi servorum

In manibus dominorum suorum.

Sicut oculi ancillae in manibus dominae suae

ita oculi nostri ad Dominum Deum nostrum,

Donec misereatur nostri.

Miserere nostri Domine…

Adèle seized Reynevan by the back of the neck and pulled him onto her. Reynevan, understanding what was required of him, made love to her powerfully and passionately, whispering assurances of devotion into her ear. He was happy. Very happy.

Reynevan owed the happiness intoxicating him to the Lord’s saints—indirectly, of course—as follows:

Feeling remorse for some sins or other—known only to himself and his confessor—the Silesian knight Gelfrad of Stercza had set off on a penitential pilgrimage to the grave of Saint James. But on the way, he decided that Compostela was definitely too far, and that a pilgrimage to Saint-Gilles would absolutely suffice. But Gelfrad wasn’t fated to reach Saint-Gilles, either. He only made it to Dijon, where by chance he met a sixteen-year-old Burgundian, the gorgeous Adèle of Beauvoisin. Adèle, who utterly enthralled Gelfrad with her beauty, was an orphan, and her two hell-raising and good-for-nothing brothers gave their sister to be married to the Silesian knight without a second thought. Although, in the brothers’ opinion, Silesia lay somewhere between the Tigris and the Euphrates, Stercza was the ideal brother-in-law in their eyes because he didn’t argue too much over the dowry. Thus, the Burgundian came to Heinrichsdorf, a village near Ziębice held in endowment by Gelfrad. While in Ziębice, Adèle caught Reinmar of Bielawa’s eye. And vice versa.

“Aaaah!” screamed Adèle of Stercza, wrapping her legs around Reynevan’s back. “Aaaaa-aaah!”

Never would those moans have occurred, and nothing more than surreptitious glances and furtive gestures have passed between them, if not for a third saint: George, to be precise. For on Saint George’s Day, Gelfrad of Stercza had sworn an oath and joined one of the many anti-Hussite crusades organised by the Brandenburg Prince-Elector and the Meissen margraves. The crusaders didn’t achieve any great victories—they entered Bohemia and left very soon after, not even risking a skirmish with the Hussites. But although there was no fighting, there were casualties, one of which turned out to be Gelfrad, who fractured his leg very badly falling from his horse and was still recuperating somewhere in Pleissnerland. Adèle, a grass widow, staying in the meanwhile with her husband’s family in Bierutów, was able to freely tryst with Reynevan in a chamber in the complex of the Augustinian priory in Oleśnica, not far from the hospice where Reynevan had his workshop.

The monks in the Church of Corpus Christi began to sing the second of three psalms making up the Sext. We’ll have to hurry, thought Reynevan. During the capitulum, at the latest the Kyrie, and not a moment after, Adèle must vanish from the hospice. She cannot be seen here.

Benedictus Dominus

qui non dedit nos

in captionem dentibus eorum.

Anima nostra sicut passer erepta est

de laqueo venantium…

Reynevan kissed Adèle’s hip, and then, inspired by the monks’ singing, took a deep breath and plunged himself into her orchard of pomegranates. Adèle tensed, straightened her arms and dug her fingers in his hair, augmenting his biblical initiatives with gentle movements of her hips.

“Oh, oooooh… Mon amour… Mon magicien… My divine boy… My sorcerer…”

Qui confidunt in Domino, sicut mons Sion

non commovebitur in aeternum,

qui habitat in Hierusalem…

The third already, thought Reynevan. How fleeting are these moments of happiness…

“Revertere,” he muttered, kneeling. “Turn around, turn around, Shulamith.”

Adèle turned, knelt and leaned forward, seizing the lindenwood planks of the bedhead tightly and presenting Reynevan with her entire ravishingly gorgeous posterior. Aphrodite Kallipygos, he thought, moving closer. The ancient association and erotic sight made him approach like the aforementioned Saint George, charging with his lance thrust out towards the dragon of Silene. Kneeling behind Adèle like King Solomon behind the throne of wood of the cedar of Lebanon, he seized her vineyards of Engedi in both hands.

“May I compare you, my love,” he whispered, bent over a neck as shapely as the Tower of David, “may I compare you to a mare among Pharaoh’s chariots.”

And he did. Adèle screamed through clenched teeth. Reynevan slowly slid his hands down her sides, slippery with sweat, and the Burgundian threw back her head like a mare about to clear a jump.

Gloria Patri, et Filio et Spiritui sancto.

Sicut erat in principio, et nunc, et semper

et in saecula saeculorum, Amen.

Alleluia!

As the monks concluded the Gloria, Reynevan, kissing the back of Adèle of Stercza’s neck, placed his hand beneath her orchard of pomegranates, engrossed, mad, like a young hart skipping upon the mountains to his beloved…

A mailed fist struck the door, which thudded open with such force that the lock was torn off the frame and shot through the window like a meteor. Adèle screamed shrilly as the Stercza brothers burst into the chamber.

Reynevan tumbled out of bed, positioning it between himself and the intruders, grabbed his clothes and began to hurriedly put them on. He largely succeeded, but only because the brothers Stercza had directed their frontal attack at their sister-in-law.

“You vile harlot!” bellowed Morold of Stercza, dragging a naked Adèle from the bedclothes.

“Wanton whore!” chimed in Wittich, his older brother, while Wolfher—next oldest after Adèle’s husband Gelfrad—did not even open his mouth, for pale fury had deprived him of speech. He struck Adèle hard in the face. The Burgundian screamed. Wolfher struck her again, this time backhanded.

“Don’t you dare hit her, Stercza!” yelled Reynevan, but his voice broke and trembled with fear and a paralysing feeling of impotence, caused by his trousers being round his knees. “Don’t you dare!”

His cry achieved its effect, although not the way he had intended. Wolfher and Wittich, momentarily forgetting their adulterous sister-in-law, pounced on Reynevan, raining down a hail of punches and kicks on the boy. He cowered under the blows, but rather than defend or protect himself, he stubbornly pulled on his trousers as though they were some kind of magical armour. Out of the corner of one eye, he saw Wittich drawing a knife. Adèle screamed.

“Don’t,” Wolfher snapped at his brother. “Not here!”

Reynevan managed to get onto his knees. Wittich, face white with fury, jumped at him and punched him, throwing him to the floor again. Adèle let out a piercing scream which broke off as Morold struck her in the face and pulled her hair.

“Don’t you dare…” Reynevan groaned “… hit her, you scoundrels!”

“Bastard!” yelled Wittich. “Just you wait!”

Wittich leaped forward, punched and kicked once and twice. Wolfher stopped him at the third.

“Not here,” Wolfher repeated calmly, but it was a baleful calm. “Into the courtyard with him. We’ll take him to Bierutów. That slut, too.”

“I’m innocent!” wailed Adèle of Stercza. “He bewitched me! Enchanted me! He’s a sorcerer! Sorcier! Diab—”

Morold silenced her with another punch. “Hold your tongue, trollop,” he growled. “You’ll get the chance to scream. Just wait a while.”

“Don’t you dare hit her!” yelled Reynevan.

“We’ll give you a chance to scream, too, little rooster,” Wolfher added, still menacingly calm. “Come on, out with him.”

The Stercza brothers threw Reynevan down the garret’s steep stairs and the boy tumbled onto the landing, splintering part of the wooden balustrade. Before he could get up, they seized him again and threw him out into the courtyard, onto sand strewn with steaming piles of horse shit.

“Well, well, well,” said Nicolaus of Stercza, the youngest of the brothers, barely a stripling, who was holding the horses. “Look who’s stopped by. Could it be Reinmar of Bielawa?”

“The scholarly braggart Bielawa,” snorted Jentsch of Knobelsdorf, known as Eagle Owl, a comrade and relative of the Sterczas. “The arrogant know-all Bielawa!”

“Shitty poet,” added Dieter Haxt, another friend of the family. “Bloody Abélard!”

“And to prove to him we’re well read, too,” said Wolfher as he descended the stairs, “we’ll do to him what they did to Abélard when he was caught with Héloïse. Well, Bielawa? How do you fancy being a capon?”

“Go fuck yourself, Stercza.”

“What? What?” Although it seemed impossible, Wolfher Stercza had turned even paler. “The rooster still has the audacity to open his beak? To crow? The bullwhip, Jentsch!”

“Don’t you dare beat him!” Adèle called impotently as she was led down the stairs, now clothed, albeit incompletely. “Don’t you dare! Or I’ll tell everyone what you are like! That you courted me yourself, pawed me and tried to debauch me behind your brother’s back! That you swore vengeance on me if I spurned you! Which is why you are so… so…”

She couldn’t find the German word and the entire tirade fell apart. Wolfher just laughed.

“Verily!” he mocked. “People will listen to the Frenchwoman, the lewd strumpet. The bullwhip, Eagle Owl!”

The courtyard was suddenly awash with black Augustinian habits.

“What is happening here?” shouted the venerable Prior Erasmus Steinkeller, a bony and sallow old man. “Christians, what are you doing?”

“Begone!” bellowed Wolfher, cracking the bullwhip. “Begone, shaven-heads, hurry off to your prayer books! Don’t interfere in knightly affairs, or woe betide you, blackbacks!”

“Good Lord.” The prior put his liver-spotted hands together. “Forgive them, for they know not what they do. In nomine Patris, et Filii—”

“Morold, Wittich!” roared Wolfher. “Bring the harlot here! Jentsch, Dieter, bind her paramour!”

“Or perhaps,” snarled Stefan Rotkirch, another friend of the family who had been silent until then, “we’ll drag him behind a horse a little?”

“We could. But first, we’ll give him a flogging!”

Wolfher aimed a blow with the horsewhip at the still-prone Reynevan but did not connect, as his wrist was seized by Brother Innocent, nicknamed by his fellow friars “Brother Insolent,” whose impressive height and build were apparent despite his humble monkish stoop. His vicelike grip held Wolfher’s arm motionless.

Stercza swore coarsely, jerked himself away and gave the monk a hard shove. But he might as well have shoved the tower in Oleśnica Castle for all the effect it had. Brother Innocent didn’t budge an inch. He shoved Wolfher back, propelling him halfway across the courtyard and dumping him in a pile of muck.

For a moment, there was silence. And then they all rushed the huge monk. Eagle Owl, the first to attack, was punched in the teeth and tumbled across the sand. Morold of Stercza took a thump to the ear and staggered off to one side, staring vacantly. The others swarmed over the Augustinian like ants, raining blows on the monk’s huge form. Brother Insolent retaliated just as savagely and in a distinctly unchristian way, quite at odds with Saint Augustine’s rule of humility.

The sight enraged the old prior. He flushed like a beetroot, roared like a lion and rushed into the fray, striking left and right with heavy blows of his rosewood crucifix.

“Pax!” he bellowed as he struck. “Pax! Vobiscum! Love thy neighbour! Proximum tuum! Sicut te ipsum! Whoresons!”

Dieter Haxt punched him hard. The old man was flung over backwards and his sandals flew up, describing pretty trajectories in the air. The Augustinians cried out and several of them charged into battle, unable to restrain themselves. The courtyard was seething in earnest.

Wolfher of Stercza, who had been shoved out of the confusion, drew a short sword and brandished it—bloodshed looked inevitable. But Reynevan, who had finally managed to stand up, whacked him in the back of the head with the handle of the bullwhip he had picked up. Stercza held his head and turned around, only for Reynevan to lash him across the face. As Wolfher fell to the ground, Reynevan rushed towards the horses.

“Adèle! Here! To me!”

Adèle didn’t even budge, and the indifference painted on her face was alarming. Reynevan leaped into the saddle. The horse neighed and fidgeted.

“Adèèèèle!”

Morold, Wittich, Haxt and Eagle Owl were now running towards him. Reynevan reined the horse around, whistled piercingly and spurred it hard, making for the gate.

“After him!” yelled Wolfher. “To your horses and get after him!”

Reynevan’s first thought was to head towards Saint Mary’s Gate and out of the town into the woods, but the stretch of Cattle Street leading to the gate was totally crammed with wagons. Furthermore, the horse, urged on and frightened by the cries of an unfamiliar rider, was showing great individual initiative, so before he knew it, Reynevan was hurtling along at a gallop towards the town square, splashing mud and scattering passers-by. He didn’t have to look back to know the others were hot on his heels given the thudding of hooves, the neighing of horses, the angry roaring of the Sterczas and the furious yelling of people being jostled.

He jabbed the horse to a full gallop with his heels, hitting and knocking over a baker carrying a basket. A shower of loaves and pastries flew into the mud, soon to be trodden beneath the hooves of the Sterczas’ horses. Reynevan didn’t even look back, more concerned with what was ahead of him than behind. A cart piled high with faggots of brushwood loomed up before his eyes. The cart was blocking almost the entire street, the rest of which was occupied by a group of half-clothed urchins, kneeling down and busily digging something extremely engrossing out of the muck.

“We have you, Bielawa!” thundered Wolfher from behind, also seeing the obstruction.

Reynevan’s horse was racing so swiftly there was no chance of stopping it. He pressed himself against its mane and closed his eyes. As a result, he didn’t see the half-naked children scatter with the speed and grace of rats. He didn’t look back, so nor did he see a peasant in a sheepskin jerkin turn around, somewhat stupefied, as he hauled a cart into the road. Nor did he see the Sterczas riding broadside into the cart. Nor Jentsch of Knobelsdorf soaring from the saddle and sweeping half of the faggots from the cart with his body.

Reynevan galloped down Saint John’s Street, between the town hall and the burgermeister’s house, hurtling at full speed into Oleśnica’s huge and crowded town square. Pandemonium erupted. Aiming for the southern frontage and the squat, square tower of the Oława Gate visible above it, Reynevan galloped through the crowds, leaving havoc behind him. Townsfolk yelled and pigs squealed, as overturned stalls and benches showered a hail of household goods and foodstuffs of every kind in all directions. Clouds of feathers flew everywhere as the Sterczas—hot on Reynevan’s heels—added to the destruction.

Reynevan’s horse, frightened by a goose flying past its nose, recoiled and hurtled into a fish stall, shattering crates and bursting open barrels. The enraged fishmonger made a great swipe with a keep net, missing Reynevan but striking the horse’s rump. The horse whinnied and slewed sideways, upending a stall selling thread and ribbons, and only a miracle prevented Reynevan from falling. Out of the corner of one eye, he saw the stallholder running after him brandishing a huge cleaver (serving God only knew what purpose in the haberdashery trade). Spitting out some goose feathers stuck to his lips, he brought the horse under control and galloped through the shambles, knowing that the Oława Gate was very close.

“I’ll tear your balls off, Bielawa!” Wolfher of Stercza roared from behind. “I’ll tear them off and stuff them down your throat!”

“Kiss my arse!”

Only four men were chasing him now—Rotkirch had been pulled from his horse and was being roughed up by some infuriated market traders.

Reynevan darted like an arrow down an avenue of animal carcasses suspended by their legs. Most of the butchers leaped back in alarm, but one carrying a large haunch of beef on one shoulder tumbled under the hooves of Wittich’s horse, which took fright, reared up and was ploughed into by Wolfher’s horse. Wittich flew from the saddle straight onto the meat stall, nose-first into livers, lights and kidneys, and was then landed on by Wolfher. His foot was caught in the stirrup and before he could free himself, he had smashed a large number of stalls and covered himself in mud and blood.

At the last moment, Reynevan quickly lowered his head over the horse’s neck to duck under a wooden sign with a piglet’s head painted on it. Dieter Haxt, who was bearing down on him, wasn’t quick enough and the cheerfully grinning piglet slammed into his forehead. Dieter flew from the saddle and crashed into a pile of refuse, frightening some cats. Reynevan turned around. Now only Nicolaus of Stercza was keeping up with him.

Reynevan shot out of the chaos at a full gallop and into a small square where some tanners were working. As a frame hung with wet hides loomed up before him, he urged his horse to jump. It did. And Reynevan didn’t fall off. Another miracle.

Nicolaus wasn’t as lucky. His horse skidded to a halt in front of the frame and collided with it, slipping on the mud and scraps of meat and fat. The youngest Stercza shot over his horse’s head, with very unfortunate results. He flew belly-first right onto a scythe used for scraping leather which the tanners had left propped up against the frame.

At first, Nicolaus had no idea what had happened. He got up from the ground, caught hold of his horse, and only when it snorted and stepped back did his knees sag and buckle beneath him. Still not really knowing what was happening, the youngest Stercza slid across the mud after the panicked horse, which was still moving back and snorting. Finally, as he released the reins and tried to get to his feet again, he realised something was wrong and looked down at his midriff.

And screamed.

He dropped to his knees in the middle of a rapidly spreading pool of blood.

Dieter Haxt rode up, reined in his horse and dismounted. A moment later, Wolfher and Wittich followed suit.

Nicolaus sat down heavily. Looked at his belly again. Screamed and then burst into tears. His eyes began to glaze over as the blood gushing from him mingled with the blood of the oxen and hogs butchered that morning.

“Nicolaaaaus!” yelled Wolfher.

Nicolaus of Stercza coughed and choked. And died.

“You are dead, Reinmar of Bielawa!” Wolfher of Stercza, pale with fury, bellowed towards the gate. “I’ll catch you, kill you, destroy you. Exterminate you and your entire viperous family. Your entire viperous family, do you hear?”

Reynevan didn’t. Amid the thud of horseshoes on the bridge planks, he was leaving Oleśnica and dashing south, straight for the Wrocław highway.

In which the reader finds out more about Reynevan from conversations involving various people, some kindly disposed and others quite the opposite. Meanwhile, Reynevan himself is wandering around the woods near Oleśnica. The author is sparing in his descriptions of that trek, hence the reader—nolens volens—will have to imagine it.

“Sit you down, gentlemen,” said Bartłomiej Sachs, the burgermeister of Oleśnica, to the councillors. “What’s your pleasure? Truth be told, I have no wines to regale you with. But ale, ho-ho, today I was brought some excellent matured ale, first brew, from a deep, cold cellar in Świdnica.”

“Beer it is, then, Master Bartłomiej,” said Jan Hofrichter, one of the town’s wealthiest merchants, rubbing his hands together. “Ale is our tipple, let the nobility and diverse lordlings pickle their guts in wine… With my apologies, Reverend…”

“Not at all,” replied Father Jakub of Gall, parish priest at the Church of Saint John the Evangelist. “I’m no longer a nobleman, I’m a parson. And a parson, naturally, is ever with his flock, thus it doesn’t behove me to disdain beer. And I may drink, for Vespers have been said.”

They sat down at the table in the huge, low-ceilinged, whitewashed chamber of the town hall, the usual location for meetings of the town council. The burgermeister was in his customary seat, back to the fireplace, with Father Gall beside him, facing the window. Opposite sat Hofrichter, beside him Łukasz Friedmann, a sought-after and wealthy goldsmith, in his fashionably padded doublet, a velvet beret resting on curled hair, every inch the nobleman.

The burgermeister cleared his throat and began, without waiting for the servant to bring the beer. “And what is this?” he said, linking his hands on his prominent belly. “What have the noble knights treated us to in our town? A brawl at the Augustinian priory. A chase on horseback through the streets. A disturbance in the town square, several folk injured, including one child gravely. Belongings destroyed, goods marred—such significant material losses that mercatores et institores were pestering me for hours with demands for compensation. In sooth, I ought to pack them off with their plaints to the Lords Stercza!”

“Better not,” Jan Hofrichter advised dryly. “Though I also hold that our noblemen have been lately passing unruly, one can neither forget the causes of the affair nor of its consequences. For the consequence—the tragic consequence—is the death of young Nicolaus of Stercza. And the cause: licentiousness and debauchery. The Sterczas were defending their brother’s honour, pursuing the adulterer who seduced their sister-in-law and besmirched the marital bed. In truth, in their zeal they overplayed a touch—”

The merchant stopped speaking under Father Jakub’s telling gaze. For when Father Jakub signalled with a look his desire to express himself, even the burgermeister himself fell silent. Jakub Gall was not only the parish priest of the town’s church, but also secretary to Konrad, Duke of Oleśnica, and canon in the Chapter of Wrocław Cathedral.

“Adultery is a sin,” intoned the priest, straightening his skinny frame behind the table. “Adultery is also a crime. But God punishes sins and the law punishes crimes. Nothing justifies mob law and killings.”

“Yes, yes,” agreed the burgermeister, but fell silent at once and devoted all his attention to the beer that had just arrived.

“Nicolaus of Stercza died tragically, which pains us greatly,” added Father Gall, “but as the result of an accident. However, had Wolfher and company caught Reinmar of Bielawa, we would be dealing with a murder in our jurisdiction. We know not if there might yet be one. Let me remind you that Prior Steinkeller, the pious old man severely beaten by the Sterczas, is lying as if lifeless in the Augustinian priory. If he expires as a result of the beating, there’ll be a problem. For the Sterczas, to be precise.”

“Whereas, regarding the crime of adultery,” said the goldsmith Łukasz Friedmann, examining the rings on his manicured fingers, “mark, honourable gentlemen, that it is not our jurisdiction at all. Although the debauchery occurred in Oleśnica, the culprits do not come under our authority. Gelfrad of Stercza, the cuckolded husband, is a vassal of the Duke of Ziębice. As is the seducer, the young physician, Reinmar of Bielawa—”

“The debauchery took place here, as did the crime,” said Hofrichter firmly. “And it was a serious one, if we are to believe what Stercza’s wife disclosed at the Augustinian priory—that the physician beguiled her with spells and used sorcery to entice her to sin. He compelled her against her will.”

“That’s what they all say,” the burgermeister boomed from the depths of his mug.

“Particularly when someone of Wolfher of Stercza’s ilk holds a knife to their throat,” the goldsmith added without emotion. “The Reverend Father Jakub was right to say that adultery is a felony—a crimen—and as such demands an investigation and a trial. We do not wish for familial vendettas or street brawls. We shall not allow enraged lordlings to raise a hand against men of the cloth, wield knives or trample people in city squares. In Świdnica, a Pannewitz went to the tower for striking an armourer and threatening him with a dagger. Which is proper. The times of knightly licence must not return. The case must go before the duke.”

“All the more so since Reinmar of Bielawa is a nobleman and Adèle of Stercza a noblewoman,” the burgermeister confirmed with a nod. “We cannot flog him, nor banish her from the town like a common harlot. The case must come before the duke.”

“Let’s not be too hasty with this,” said Father Gall, gazing at the ceiling. “Duke Konrad is preparing to travel to Wrocław and has a multitude of matters to deal with before his departure. The rumours have probably already reached him—as rumours do—but now isn’t the time to make them official. Suffice it to postpone the matter until his return. Much may be resolved by then.”

“I concur.” Bartłomiej Sachs nodded again.

“As do I,” added the goldsmith.

Jan Hofrichter straightened his marten-fur calpac and blew the froth from his mug. “For the present, we ought not to inform the duke,” he pronounced. “We shall wait until he returns, I agree with you on that, honourable gentlemen. But we must inform the Holy Office, and fast, about

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...