- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

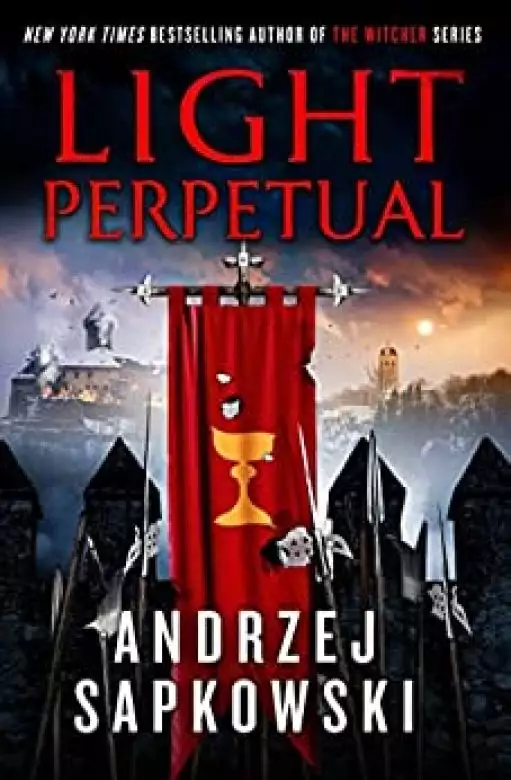

The epic conclusion to the Hussite Trilogy by the bestselling author of The Witcher finds Reynevan - infamous magician and disgraced scoundrel - on the run after being sentenced to death by the Catholic Church.

Reynevan is besieged on all sides and faces torture and execution if he makes any mistake in his quest to find his beloved, Jutta of Apolda. Aided by his companions - the ever-pragmatic Scharley and the mysterious being known as Samson Honeypot - his journey takes him all over the Bohemian realm.

And Reynevan will need every ounce of his wit, intelligence and cunning if he is to succeed in his search. The political and religious alliances of the Hussite Wars are ever shifting, and the battle for dominance threatens to devour anyone who gets in their way.

Faced too with dark magical forces summoned by the malevolent Birkart of Grellenort, aided by his terrifying band of Back Riders, Reynevan knows the odds of finding Jutta decrease with every obstacle he is forced to overcome along the way. But he has never let impossible odds stop him before - and he will be reunited with his love, whatever the cost.

Release date: October 25, 2022

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Light Perpetual

Andrzej Sapkowski

The morning was foggy, and quite mild for February. There had been a hint of a thaw in the air all night; the snow began melting at dawn, and the prints of iron-shod hooves and the ruts made by wagon wheels filled at once with black water. Axles and swingletrees creaked, horses snorted and wagoners cursed drowsily. The column of almost three hundred wagons made slow progress. The pungent, choking smell of salt herrings hung over the column. Sir John Fastolf rocked sleepily in the saddle.

A thaw had suddenly set in after a few days of frost, and the wet snow that had been falling all night quickly melted. Water dripped from the snow lying heavily on spruce trees.

“Haaave at theeem! Kill them!”

“Haaaa!”

The noise of the sudden battle frightened some rooks. The birds flew up from leafless branches, the leaden February sky became flecked with a shifting black mosaic and the chilly, damp air was filled with cawing. The clang and thud of iron. And yells.

The fighting was short-lived but fierce. Hooves ploughed up the slush, mixing it with mud. Horses whinnied and squealed shrilly. Men uttered cries, some warlike and others of pain. It began suddenly and was soon over.

“Huzza! Cut them oooff! Cut them ooooff!”

Then again, more quietly, further off, the echo bounced around the forest.

“Huzza! Huzzaaa!”

The rooks cawed, circling above the trees. The thudding of hooves receded. The shouts died away.

Blood stained the puddles, soaked into the snow.

The wounded esquire heard the rider approaching, alerted by the snorting of a horse and the jangling of a bridle. He groaned, tried to stand up but fell back. His efforts intensified the bleeding, the crimson stream pulsating more strongly between the plates of his cuirass and flowing down the armour. The wounded man settled back harder against a fallen tree trunk and drew a dagger. Aware how feeble a weapon it was in the hand of a man who couldn’t stand, whose side had been pierced by a spear and whose ankle was twisted after falling from his horse.

The approaching bay colt was a pacing horse, its unusual gait immediately visible. The bay’s rider didn’t have the sign of the Chalice on his chest, so wasn’t one of the Hussites the esquire’s troop had just been fighting. He wasn’t wearing armour. Or carrying a weapon. He looked like an ordinary traveller. The wounded esquire knew only too well, though, that in the month of February Anno Domini 1429, no one was simply travelling in the Strzegom hills or the Jawor plain.

The rider examined him at length from the height of his saddle. At length and wordlessly.

“That bleeding needs staunching,” he finally said. “I can do it, but only if you toss that dagger aside. If you don’t, I’ll ride off and you can cope by yourself. Decide.”

“No one…” the esquire grunted. “No one will pay a ransom for me… So don’t say I didn’t warn you—”

“Will you toss the dagger aside or not?”

The esquire swore softly, took a big swing and flung the dagger away. The rider dismounted, unfastened his saddlebags, then knelt down beside him, holding a leather bag. He used a short folding knife to cut through the straps attaching the two parts of the breastplate to the cuirass. After removing the armour, he slashed open the blood-soaked gambeson and looked intently, bending low over the wound.

“Nasty…” he muttered. “Looks very nasty. Vulnus punctum, a stab wound. It’s deep… I’ll put on a dressing, but can do no more without help. I’ll carry you to Strzegom.”

“Strzegom… besieged… Hussites…”

“I know. Don’t move.”

“I think…” The esquire panted. “I think I know you.”

“Well, I never, your face looks familiar to me, too.”

“I am Wilkosz Lindenau… The esquire of Lord Borschnitz, may God rest his soul… The tournament in Ziębice… I escorted you to the tower… For you are… For you are Reinmar of Bielawa… Aren’t you?”

“Aha.”

“Why, it’s you,” said the esquire, his eyes opening wide in terror. “Christ. It is you.”

“Accursed at home and excommunicated abroad? Indeed. It’s going to hurt now.”

The esquire clenched his teeth hard. Just in time.

Reynevan led his horse. Hunched over in the saddle, Wilkosz Lindenau groaned and moaned.

Beyond the hill and forest was a road, and beside it, not far away, some blackened ruins, the remains of demolished buildings that Reynevan could just about recognise as the former Carmelite monastery of the Order of Beatissimae Virginis Mariae de Monte Carmeli, which had once served as a house of correction, a place of isolation and punishment for sinful priests. And beyond it was Strzegom. Currently under siege.

The army besieging Strzegom was large; at first glance, Reynevan estimated it to be a good five or six thousand men, thus confirming the rumours that the Orphans had gained reinforcements from Moravia. The previous December, Jan Královec had led a plundering raid on Silesia with a force of almost four thousand soldiers and a proportional number of war wagons and artillery. There were a good five hundred wagons at Strzegom and as far as the artillery was concerned, it was time to put on a show. Around ten bombards and mortars roared, shrouding the artillery positions and approaches in smoke. Stone balls whistled towards the town, slamming into the walls and buildings. Reynevan knew what the targets were from the missile strikes: the Dziobowa Tower and the tower over the Świdnica Gate—the main bastions on the southern and eastern sides—along with the magnificent town houses in the town square and the parish church. Jan Královec of Hrádek was a seasoned commander and knew whom to torment and whose property to destroy. How long a city defended itself usually depended on the morale of the Patriciate and the clergy.

In principle, one might have expected a storming after the salvo, but there was nothing to suggest it.

The duty detachments were firing crossbows, hook guns and trestle guns from behind earthworks, but the remaining Orphans were lazing about around campfires and the cauldrons in the camp kitchens. Nor was there any heightened activity in the vicinity of the senior officers’ tents, over which standards with the Chalice and the Pelican were waving listlessly.

Reynevan was leading his horse towards the headquarters. The Orphans he passed showed little interest in them; no one stopped them, no one shouted a challenge or asked who they were. The Orphans might have recognised Reynevan; many knew him, after all. They might just have been uninterested.

“They’ll slit my throat…” muttered Lindenau from the saddle. “They’ll slash me to ribbons… Heretics… Hussites… Devils.”

“They won’t touch you,” said Reynevan, trying to convince himself as a patrol armed with bear spears and gisarmes approached them. “But to be on the safe side, say ‘Czechs.’ Greetings, Brothers! I am Reinmar Bielawa—do you know me? We need a physician! A medic! Call a physician please!”

The moment Reynevan entered the headquarters, Brázda of Klinštejn hugged and kissed him, after which Jan Kolda of Žampach, the brothers Matěj and Jan Salava of Lípa, Vilém Jeník and others he didn’t know began to shake his hand and slap him on the back. Jan Královec of Hrádek, Hejtman of the Orphans and leader of the expedition, gave no lavish display of emotion. And didn’t look surprised, either.

“Reynevan,” he said, greeting him quite coolly. “Well, I never. Welcome, O prodigal son. I knew you’d return to us.”

“It’s time we finished it,” said Jan Královec of Hrádek.

He was showing Reynevan around the lines and positions. They were alone. Královec wanted them to be alone. He wasn’t certain who had sent Reynevan and with what information and was expecting confidential messages intended for his ears only. Having learned that Reynevan was nobody’s envoy and was bringing no messages, his face darkened.

“It’s time we finished it,” he repeated, climbing up onto an earthwork and measuring with a hand the temperature of a bombard’s barrel, which was being cooled with untreated animal hides soaked in water.

He glanced up at the walls and towers of Strzegom. Reynevan was still looking back at what was left of the Carmelite monastery. The place, where—an absolute eternity ago—he had first met Scharley. An absolute eternity, he thought. Four years.

“Time we finished it.” Královec’s voice shook him out of his reverie and recollections. “It’s high time. We’ve done our job. December and January were enough for us to capture and sack Duszniki, Bystrzyca, Ziębice, Strzelin, Niemcza, the Cistercian abbey and monastery in Henryków, plus innumerable small towns and villages. We taught the Germans a lesson, they won’t forget us. But Shrovetide is past, it is Ash Wednesday, the ninth day of February. We’ve been warring for well over two months and during winter months at that! We must have marched a good forty miles. We are hauling behind us wagons heavy with spoils, driving herds of cattle. And morale is falling, the men are weary. Świdnica, outside which we were encamped for five whole days, repelled us. I’ll tell you the truth, Reynevan: we didn’t have the force to storm it. We fired cannons, hurled fire onto the rooftops and spread terror, thinking the people of Świdnica would surrender or at least wish to parley, pay a ransom. But Lord Kolditz was undaunted and we had to leave there empty-handed. Strzegom has clearly taken heart, for it also holds out valiantly. And once again we intimidate, sow terror, fire cannons and chase around the forests with Wrocław patrols trying to beset us. But I’ll be frank: we’ll have to leave here empty-handed, too. And go home. For it is time. What do you think?”

“I don’t think anything. You’re in command here.”

“I am, I am,” said the hejtman, spinning around on his heel. “In command of an army whose morale is failing fast. But you, Reynevan, shrug and think nothing. And what do you do? You save a stricken German. A papist. You bring him here, ordering our medic to treat him. You show a foe mercy. Before everybody’s eyes? You should have slit his throat in the bloody forest.”

“You cannot be serious.”

“I swore…” Královec snarled through his teeth. “That after Oława… After Oława, I vowed I would show mercy to none of them. None.”

“We can’t stop being people.”

“People?” said the Hejtman of the Orphans, almost frothing at the mouth. “People? Do you know what happened in Oława? On Saint Anthony’s Eve? If you’d been there, you’d have seen it.”

“I was, and I did.” Observing unemotionally the hejtman’s astonished expression, Reynevan repeated: “I was in Oława. I ended up there a few days after Epiphany, soon after you left. I was in the town on the Sunday before Saint Anthony’s. And I saw it all. I also witnessed the triumph that Wrocław celebrated because of Oława.”

Královec said nothing for a moment, gazing from the earthwork at the bell tower of Strzegom parish church, where the bell had begun to toll, resonantly and sonorously.

“Why, you weren’t only in Oława, but also in Wrocław.” He stated the fact. “And now you’ve come here, to Strzegom. Like a bolt from the blue. You come and go. How and from where—no one knows. People have begun to talk, to gossip. To suspect.”

“Suspect what?”

“Easy, easy, don’t take umbrage. I trust you. I know you had important matters to deal with. When you bade us farewell on the battlefield at Wielisław on the twenty-seventh of December, we saw that you were hastening to attend to some important—extremely important—matters. How did you fare?”

“I solved nothing,” said Reynevan, without concealing his bitterness. “But I am cursed. Cursed standing, working and sitting. In the hills and the vales.”

“How so?”

“It’s a long story.”

“I adore long stories.”

The fact that something uncommon would happen that day in Wrocław Cathedral was communicated to the congregation gathered within by the excited murmurings of the people standing closer to the transept and the chancel. The latter could see and hear more than the rest, who were crammed tightly into the nave and the aisles. Initially, they had to settle for guesses. And rumours borne in a swelling, repeating whisper that spread through the crowd like the rustle of leaves in the wind.

The great bell of Ostrów Tumski began to toll, hollowly and slowly, ominously and grimly, and also intermittently, since it could clearly be heard that the clapper was striking only one side of the bronze bell. Elencza of Stietencron grasped Reynevan’s hand and squeezed it hard. Reynevan squeezed back.

Exaudi Deus orationem meam cum deprecor

a timore inimici eripe animam meam…

The portal leading to the vestry was graced by reliefs portraying the martyr’s death of Saint John the Baptist, the cathedral’s patron. A dozen prelates, members of the chapter, were emerging from the portal, singing. Attired in ceremonial surplices, grasping fat candles, the prelates paused before the main altar, facing the nave.

Protexisti me a conventu malignantium

a multitudine operantium iniquitatem

quia exacuerunt ut gladium linguas suas

intenderunt arcum rem amaram

ut sagittent in occultis immaculatum…

The murmur of the crowd suddenly grew in intensity. For on the steps of the altar had appeared in person Konrad, Bishop of Wrocław, a Piast from the line of the Oleśnica dukes. The highest-ranking ecclesiastical dignitary in Silesia, the representative of His Majesty Sigismund of Luxembourg, King of Hungary and Bohemia.

The bishop was in full pontifical regalia. Bearing a mitre decorated with gemstones, a dalmatic worn over a tunicle, a pectoral cross on his chest and a crosier coiled like a pretzel in his hand, he looked distinguished indeed. He was veiled in an aura of such dignity that you’d have thought it wasn’t just any old Wrocław bishop descending the steps of the altar, but an archbishop, an elector, a metropolitan bishop, a cardinal—why, even the Roman Pope himself. Perhaps a man even more dignified and more pious than the incumbent Roman Pope. Considerably more dignified and pious. Plenty of the people gathered in the cathedral were of that opinion. As indeed was the bishop himself.

“Brothers and sisters.” His booming, resonant voice, which seemed to rumble right up to the top of the high vault, electrified and hushed the crowd. The cathedral bell tolled once again and fell silent.

“Brothers and sisters!” said the bishop, leaning on his crosier. “Good Christians! Our Lord, Jesus Christ, teaches us to forgive the wayward their sins, teaches us to pray for our enemies. It is a good and merciful teaching, a Christian teaching, but it does not pertain to every sinner. There are transgressions and sins for which there is no forgiveness, no mercy. Every sin and blasphemy will be forgiven, but blasphemy against the Spirit will not be forgiven. Neque in hoc saeculo, neque in futuro, neither in this age, nor the next.”

A deacon handed him a lit candle. The bishop extended a besleeved hand and took it.

“Reinmar Bielawa, son of Tomasz of Bielau, has sinned against the One God in the Trinity. He has committed the sins of blasphemy, sacrilege, witchcraft, apostasy. And also, when all’s said and done, a common crime.”

Elencza, still squeezing Reynevan’s hand hard, sighed deeply and looked up at his face. And sighed again, this time more softly. Reynevan’s face betrayed no emotion. It was expressionless, as though carved from stone. His face was like it was in Oława, thought Elencza in horror. In Oława, on the night of the sixteenth of January.

“The Bible speaks thus about men like Reinmar of Bielawa,” said the bishop, his voice again echoing among the cathedral’s columns and arcades. “If they flee from the decay of the world by knowing the Lord and Saviour, but later, yielding to it again, shall be vanquished, their end is worse than their beginnings. For it would be better for them not to know the way of justice than, having discovered it, turn away from the Holy Commandment given unto them. What is written has been fulfilled with them: the cur returns to what it has vomited up, and the swine once washed… to a muddy puddle.

“To its own puke,” said Konrad of Oleśnica, raising his voice yet louder, “and to a muddy puddle has returned the apostate and heretic Reinmar of Bielawa, robber, sorcerer, violator of virgins, blasphemer, defiler of sacred places, sodomite and fratricide, perpetrator of numerous crimes; a scoundrel, who ultimus diebus Decembris treacherously murdered the good and upstanding Duke Jan, Lord of Ziębice, with a knife in the back.

“Therefore, in the name of God Almighty, in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, in the name of all the Lord’s Saints, by the power invested in us, we excommunicate the apostate Reinmar of Bielawa from the confraternity of the Body and Blood of our Lord. We sever the bond cleaving him to the bosom of the Holy Church and drive him from the congregation of the faithful!”

Nothing could be heard but panting and gasps in the silence that descended in the naves. A stifled cough. A hiccup.

“Anathema sit! Excommunicated is Reinmar of Bielawa! May he be cursed in his house and garden, cursed in living and dying, standing, sitting, working and walking, cursed in the town, in the hamlet and on the soil, in the fields, in the woods, in the meads and the pastures, in the hills and in the vales. May incurable ailments, pestilence, Egyptian boils, haemorrhoids, scabies and scabs fall on his eyes, throat, tongue, mouth, neck, chest, lungs, ears, nostrils, arms and testicles; on every bodily member from the top of his head to his feet. May his house, his table and his bed be cursed, his horse and his dog. May his food and beverages be cursed, and everything he doth possess.”

Elencza felt a tear rolling down her cheek.

“We declare Reinmar Bielawa to be set about with perpetual anathema, to be flung into the abyss with Lucifer and his fallen angels. We number him among the threefold accursed with no hope for purgation. May lux, his light, for ever, for ever amen, be put out, as a sign that this excommunicate be put out of the memory of the Church and of the people. May it come to pass!”

“Fiat! Fiat! Fiat!” uttered the white-surpliced prelates in mournful voices.

Holding the candle away from himself with his arm outstretched, the bishop quickly turned it so that the flame was facing downwards and then released it. The prelates followed suit; the clatter of candles cast onto the floor combined with the smell of hot wax and soot from the wicks. The great bell tolled. Three times. And fell silent. The echo lingered for a long while until it faded into silence, high up under the vault.

There was an intense smell of wax and soot, and of steaming, damp, unwashed clothing. There was a cough; there was a hiccup. Elencza swallowed back tears.

The bell in the nearby Church of Saint Mary Magdalene announced the Nones with a double pulsatio. A moment after, it was followed by the bell of Saint Elizabeth’s, only slightly late. Outside the window of Canon Otto Beess’s chamber, Shoemakers Street resounded with a hubbub and the rattle of wheels. Otto Beess tore his eyes away from a painting depicting the martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, the only decoration on the severe walls save for a shelf with candlesticks and a crucifix.

“You’re taking a great risk, my lad,” he said. Those were the first words he had uttered after opening the door and seeing who was standing there. “You’re taking a great risk, showing up in Wrocław. I wouldn’t even call it a risk. It’s brazen lunacy.”

“Believe me, Reverend Father,” said Reynevan, lowering his eyes, “I wouldn’t come here without good cause—”

“Which I can guess at.”

“Father—”

Otto Beess slammed his hand down on the table and ordered him silent by swiftly raising the other. And said nothing for a long time.

“Just between you and me,” he finally said, “the individual whom—owing to me—you rescued from the Strzegom Carmelite monastery four years ago, following Peterlin’s murder… What did he ask you to call him?”

“Scharley.”

“Scharley, ah. Are you in touch with him?”

“Not lately. But generally speaking, yes.”

“Then should you meet that… that Scharley, tell him I have a bone to pick with him. He let me down sorely. The good sense and cunning he was famed for have gone to hell. Rather than taking you to Hungary, as he was meant to, he took you to Bohemia and dragged you into the Hussites.”

“He did not. I joined the Utraquists myself. According to my own will and choice, preceded by a lengthy consideration of the matter. And I am certain that I acted correctly. The truth is with us. I believe.”

The canon silenced him again with a raised hand. He didn’t care what Reynevan believed. The expression on his face left no doubts in that regard.

“As I said, I can guess what brought you to Wrocław,” he finally said, looking up. “I guessed it easily; the reasons are common knowledge. No one talks about anything else. For the last two months, your new fellow believers and brothers in faith, your confraters in the fight for the truth, your comrades and companions in the Chalice, have been laying waste to the Kłodzko lands and Silesia. For two months, your brothers—Královec’s Orphans—have been murdering, burning and looting in the name of faith and truth. They have sent Ziębice, Strzelin, Oława and Niemcza up in smoke, pillaged the monastery in Henryków and plundered and ransacked half of the Nadodrze. Now, word has it, they are besieging Świdnica. Then all of a sudden you appear in Wrocław.”

“Father—”

“Silence. Look me in the eyes. If you come here as a Hussite spy, a saboteur or an emissary, then leave my house immediately. Go to ground somewhere else. But not beneath my roof.”

“Your words have cut me to the quick, Reverend Father,” said Reynevan, meeting his gaze. “As has the suspicion that I would be capable of a base act like that. The thought that I would put you in harm’s way.”

“You did so by coming here. The house might be under observation.”

“I was cautious. I’m able to—”

“I know.” The canon cut him off bluntly. “And I know what you’re capable of. Rumours travel around quickly. Look me in the eyes and tell me straight: are you here as a spy or not?”

“I am not.”

“So why are you here, then?”

“I need help.”

Otto Beess raised his head and looked at the wall, at the painting depicting pagans flaying Saint Bartholomew with huge pliers. Then he fixed his gaze on Reynevan’s eyes once more.

“Oh, you do,” he said gravely. “You do indeed. And more than you think. Not only in this world, but in the next one, too. You’ve overstepped the mark, my son. Overstepped the mark. You have grown so zealous alongside your new comrades and brothers in the new faith that you have become notorious. In particular since last December, after the Battle of Wielisław. It ended the way it had to end. Now, if I may advise you: pray, be contrite and do penance. Don sackcloth and sprinkle ashes on your head, copiously. Or you’ll have no fucking chance of salvation. Do you know of what I speak?”

“I do. I was there.”

“You were? In the cathedral?”

“Indeed.”

The canon was silent for a time, drumming his fingers on the table.

“You’ve been to many places,” he finally said. “Far too many, I’m afraid. In your shoes I would curb myself. Returning ad rem: since the twenty-third of January, since Septuagesima Sunday, you are cast out of the Church. I know, I know what you’ll say to that, O Hussite. That our Church is evil and apostatic, while yours is virtuous and true. And that you care not for anathema. By all means care not, as you will. For this is neither the time nor the place for theological debates. You didn’t come here, I presume, to seek help in the matter of salvation. You think more about secular and commonplace matters, more about the profanum than the sacrum. So, speak. Tell me. Confide your woes in me. And since I must to Ostrów Tumski before Vespers, be succinct in the telling. As far as you are able.”

Reynevan sighed. And told him. Succinctly. As far as he was able. The canon heard him out. After which he sighed. Heavily.

“Oh, my boy, my boy,” he said, shaking his head. “You’re becoming bloody repetitious. All your problems are of the same ilk. Every difficulty of yours—to express it eruditely—is feminini generis.”

The earth shook under the stamping of hooves. The herd galloped across the field; gleaming flanks and rumps flashed past in a kaleidoscope of bay, black, grey, dun, dapple-grey and chestnut. Tails and thick manes flowed, steam belched from nostrils. Dzierżka of Wirsing braced herself against the pommel of her saddle with both hands, joy and delight in her eyes, as though she wasn’t a horse trader admiring her colts and mares, but a mother, her children.

“It appears, Reynevan,” she said, finally turning around, “that all your worries boil down to the same thing. Every vexation of yours, it appears, wears a frock and has a plait.”

She spurred her grey to a trot and followed the herd. He hurried after her. His mount, a magnificent bay stallion, was a pacing horse and Reynevan still wasn’t entirely accustomed to the unusual rhythm of its gait. Dzierżka waited for him to catch up.

“I can’t help you,” she said firmly. “The only thing I can do is to give you the colt you’re sitting on. Along with my blessing. And a medal of Saint Eligius, the patron saint of horses, pinned to its bridle. He is a fine steed. Strong and robust. He will serve you well. Take him from me as a gift. In gratitude for Elencza. For what you did for her.”

“I only repaid a debt, for what she once did for me. And I thank you for the horse.”

“Apart from the horse, I can only help by giving you advice. Return to Wrocław and pay Canon Otto Beess a visit. Or perhaps you already have? While you were in Wrocław with Elencza?”

“Canon Otto is out of favour with the bishop. It appears I am to blame. It may still rankle him, and he may by no means be gladdened by my visits, which might bring him harm—”

“How caring you are!” Dzierżka sat upright in the saddle. “Your visits always threaten harm. Didn’t you think about that as you rode to visit me here, in Skałka?”

“I did. But Elencza was my concern. I was afraid to let her go alone. I wanted to get her here safely—”

“I know. I’m not aggrieved that you came. But I can’t help you. Because I’m afraid.”

She pushed her sable calpac to the back of her head and wiped her face with a hand.

“They intimidated me,” she said, glancing to one side. “They put the bloody wind up me. On the twenty-fifth of September, near Frankenstein, by Grochowa Mountain. Do you remember what happened then? I was absolutely terrified, I swear. Reynevan, I don’t want to die. I don’t want to end up like Neumarkt, Throst and Pfefferkorn, and then Ratgeb, Czajka and Poschman. Like Cluger, burned to death in his home with his wife and children. I’ve stopped trading with the Czechs. I don’t talk politics. I’ve given a large donation to Wrocław Cathedral. And another, just as large, for the bishop’s crusade against the Hussites. Should the need arise, I’ll give even more. I prefer that to seeing my roof on fire one night. And Black Riders in the courtyard. I want to live. Particularly now, when—”

She broke off, pensively twisting and bending the strap of the reins in her hand.

“Elencza…” She paused again, looking away. “If she wants to, she’ll leave. I shan’t stop her. But were she to wish to stay here, in Skałka… Stay… for a long while… I wouldn’t have anything against it.”

“Keep her here. Don’t let her go off to work as a volunteer again. The girl has a heart and a vocation, but hospitals… Hospitals have stopped being safe of late. Keep her in Skałka, Madam Dzierżka.”

“I shall try. But as far as you are concerned…”

Dzierżka reined her horse around and brought it so close she was touching stirrups with Reynevan.

“You are very welcome here, kinsman. Come whenever you wish. But, by Saint Eligius, have a little decency. Have some regard for that girl, a little heart. Don’t torment her.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Don’t pour your sorrows out to Elencza about your love for another.” Dzierżka of Wirsing’s voice took on a hard tone. “Don’t confide in her about your love for another. Don’t tell her what a great love it is. And don’t make her pity you because of it. Don’t make her suffer.”

“I don’t underst—”

“Oh, you do, you do.”

“You’re right, Father,” Reynevan admitted bitterly. “Indeed, whenever there’s a problem, it’s of the female sex. And my problems are multiplying, springing up like mushrooms… But the greatest of them at this moment is Jutta. And I’m in a quandary. I have absolutely no idea what to do—”

“Well, that makes two of us,” Canon Otto Beess declared gravely. “Because I

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...