- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

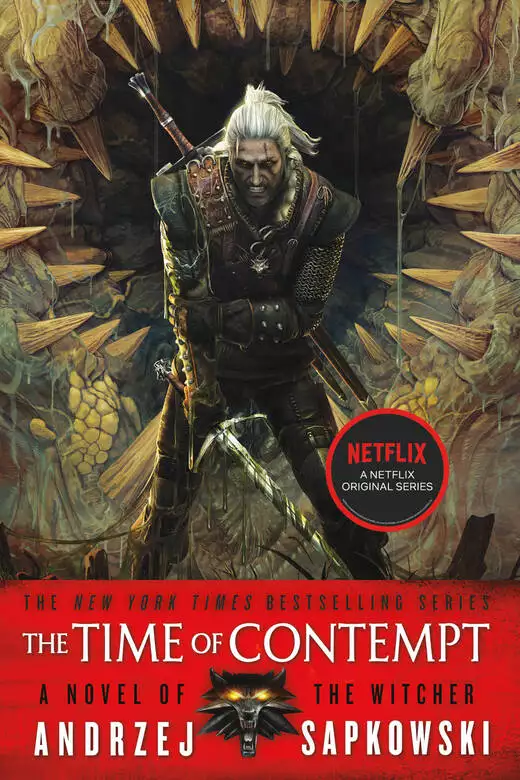

The New York Times bestselling series that inspired the international hit video game: The Witcher

Geralt is a witcher: guardian of the innocent; protector of those in need; a defender, in dark times, against some of the most frightening creatures of myth and legend. His task, now, is to protect Ciri. A child of prophecy, she will have the power to change the world for good or for ill -- but only if she lives to use it.

A coup threatens the Wizard's Guild.

War breaks out across the lands.

A serious injury leaves Geralt fighting for his life...

... and Ciri, in whose hands the world's fate rests, has vanished...

The Witcher returns in this sequel to Blood of Elves.

Witcher novels

Blood of Elves

The Time of Contempt

Baptism of Fire

The Time of Contempt

Baptism of Fire

The Tower of Swallows

Lady of the Lake

Witcher collections

The Last Wish

Sword of Destiny

The Malady and Other Stories: An Andrzej Sapkowski Sampler (e-only)

Translated from original Polish by David French

Release date: August 27, 2013

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 288

Reader says this book is...: action-packed (1) entertaining story (1) great world-building (1) high adventure (1)

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

The Time of Contempt

Andrzej Sapkowski

When talking to youngsters entering the service, Aplegatt usually told them that in order to make their living as mounted messengers two things would be necessary: a head of gold and an arse of iron.

A head of gold is essential, Aplegatt instructed the young messengers, since in the flat leather pouch strapped to his chest beneath his clothing the messenger only carries news of less vital importance, which could without fear be entrusted to treacherous paper or manuscript. The really important, secret tidings – those on which a great deal depended – must be committed to memory by the messenger and only repeated to the intended recipient. Word for word; and at times those words are far from simple. Difficult to pronounce, let alone remember. In order to memorise them and not make a mistake when they are recounted, one has to have a truly golden head.

And the benefits of an arse of iron, oh, every messenger will swiftly learn those for himself. When the moment comes for him to spend three days and nights in the saddle, riding a hundred or even two hundred miles along roads or sometimes, when necessary, trackless terrain, then it is needed. No, of course you don’t sit in the saddle without respite; sometimes you dismount and rest. For a man can bear a great deal, but a horse less. However, when it’s time to get back in the saddle after resting, it’s as though your arse were shouting, ‘Help! Murder!’

‘But who needs mounted messengers now, Master Aplegatt?’ young people would occasionally ask in astonishment. ‘Take Vengerberg to Vizima; no one could knock that off in less than four – or even five – days, even on the swiftest steed. But how long does a sorcerer from Vengerberg need to send news to a sorcerer from Vizima? Half an hour, or not even that. A messenger’s horse may go lame, but a sorcerer’s message always arrives. It never loses its way. It never arrives late or gets lost. What’s the point of messengers, if there are sorcerers everywhere, at every kingly court? Messengers are no longer necessary, Master Aplegatt.’

For some time Aplegatt had also been thinking he was no longer of any use to anyone. He was thirty-six and small but strong and wiry, wasn’t afraid of hard work and had – naturally – a head of gold. He could have found other work to support himself and his wife, to put a bit of money by for the dowries of his two as yet unmarried daughters and to continue helping the married one whose husband, the sad loser, was always unlucky in his business ventures. But Aplegatt couldn’t and didn’t want to imagine any other job. He was a royal mounted messenger and that was that.

And then suddenly, after a long period of being forgotten and humiliatingly idle, Aplegatt was once again needed. And the highways and forest tracks once again echoed to the sound of hooves. Just like the old days, messengers began to travel the land bearing news from town to town.

Aplegatt knew why. He saw a lot and heard even more. It was expected that he would immediately erase each message from his memory once it had been given, that he would forget it so as to be unable to recall it even under torture. But Aplegatt remembered. He knew why kings had suddenly stopped communicating with the help of magic and sorcerers. The news that the messengers were carrying was meant to remain a secret from them. Kings had suddenly stopped trusting sorcerers; stopped confiding their secrets in them.

Aplegatt didn’t know what had caused this sudden cooling off in the friendship between kings and sorcerers and wasn’t overly concerned about it. He regarded both kings and magic-users as incomprehensible creatures, unpredictable in their deeds – particularly when times were becoming hard. And the fact that times were now hard could not be ignored, not if one travelled across the land from castle to castle, from town to town, from kingdom to kingdom.

There were plenty of troops on the roads. With every step one came across an infantry or cavalry column, and every commander you met was edgy, nervous, curt and as self-important as if the fate of the entire world rested on him alone. The cities and castles were also full of armed men, and a feverish bustle went on there, day and night. The usually invisible burgraves and castellans now ceaselessly rushed along walls and through courtyards, angry as wasps before a storm, yelling, swearing and issuing orders and kicks. Day and night, lumbering columns of laden wagons rolled towards strongholds and garrisons, passing carts on their way back, moving quickly, unburdened and empty. Herds of frisky three-year-old mounts taken straight out of stables kicked dust up on the roads. Ponies not accustomed to bits nor armed riders cheerfully enjoyed their last days of freedom, giving stable boys plenty of extra work and other road users no small trouble.

To put it briefly, war hung in the hot, still air.

Aplegatt stood up in his stirrups and looked around. Down at the foot of the hill a river sparkled, meandering sharply among meadows and clusters of trees. Forests stretched out beyond it, to the south. The messenger urged his horse on. Time was running out.

He’d been on the road for two days. The royal order and mail had caught up with him in Hagge, where he was resting after returning from Tretogor. He had left the stronghold by night, galloping along the highway following the left bank of the Pontar, crossed the border with Temeria before dawn, and now, at noon of the following day, was already at the bank of the Ismena. Had King Foltest been in Vizima, Aplegatt would have delivered him the message that night. Unfortunately, the king was not in the capital; he was residing in the south of the country, in Maribor, almost two hundred miles from Vizima. Aplegatt knew this, so in the region of the White Bridge he left the westward-leading road and rode through woodland towards Ellander. He was taking a risk. The Scoia’tael* continued to roam the forests, and woe betide anyone who fell into their hands or came within arrowshot. But a royal messenger had to take risks. Such was his duty.

He crossed the river without difficulty – it hadn’t rained since June and the Ismena’s waters had fallen considerably. Keeping to the edge of the forest, he reached the track leading south-east from Vizima, towards the dwarven foundries, forges and settlements in the Mahakam Mountains. There were plenty of carts along the track, often being overtaken by small mounted units. Aplegatt sighed in relief. Where there were lots of humans, there weren’t any Scoia’tael. The campaign against the guerrilla elves had endured in Temeria for a year and, being harried in the forests, the Scoia’tael commandos had divided up into smaller groups. These smaller groups kept well away from well-used roads and didn’t set ambushes on them.

Before nightfall he was already on the western border of the duchy of Ellander, at a crossroads near the village of Zavada. From here he had a straight and safe road to Maribor: forty-two miles of hard, well-frequented forest track, and there was an inn at the crossroads. He decided to rest his horse and himself there. Were he to set off at daybreak he knew that, even without pushing his mount too hard, he would see the silver and black pennants on the red roofs of Maribor Castle’s towers before sundown.

He unsaddled his mare and groomed her himself, sending the stable boy away. He was a royal messenger, and a royal messenger never permits anyone to touch his horse. He ate a goodly portion of scrambled eggs with sausage and a quarter of a loaf of rye bread, washed down with a quart of ale. He listened to the gossip. Of various kinds. Travellers from every corner of the world were dining at the inn.

Aplegatt learned there’d been more trouble in Dol Angra; a troop of Lyrian cavalry had once again clashed with a mounted Nilfgaardian unit. Meve, the queen of Lyria, had loudly accused Nilfgaard of provocation – again – and called for help from King Demavend of Aedirn. Tretogor had seen the public execution of a Redanian baron who had secretly allied himself with emissaries of the Nilfgaardian emperor, Emhyr. In Kaedwen, Scoia’tael commandos, amassed into a large unit, had orchestrated a massacre in Fort Leyda. To avenge the massacre, the people of Ard Carraigh had organised a pogrom, murdering almost four hundred non-humans residing in the capital.

Meanwhile the merchants travelling from the south described the grief and mourning among the Cintran emigrants gathered in Temeria, under the standard of Marshal Vissegerd. The dreadful news of the death of Princess Cirilla, the Lion Cub, the last of the bloodline of Queen Calanthe, had been confirmed.

Some even darker, more foreboding gossip was told. That in several villages in the region of Aldersberg cows had suddenly begun to squirt blood from their udders while being milked, and at dawn the Virgin Bane, harbinger of terrible destruction, had been seen in the fog. The Wild Hunt, a spectral army galloping across the firmament, had appeared in Brugge, in the region of Brokilon Forest, the forbidden kingdom of the forest dryads; and the Wild Hunt, as is generally known, always heralds war. And a spectral ship had been spotted off Cape Bremervoord with a ghoul on board: a black knight in a helmet adorned with the wings of a bird of prey …

The messenger stopped listening; he was too tired. He went to the common sleeping chamber, dropped onto his pallet and fell fast asleep.

He arose at daybreak and was a little surprised as he entered the courtyard – he was not the first person preparing to leave, which was unusual. A black gelding stood saddled by the well, while nearby a woman in male clothing was washing her hands in the trough. Hearing Aplegatt’s footsteps she turned, gathered her luxuriant black hair in her wet hands, and tossed it back. The messenger bowed. The woman gave a faint nod.

As he entered the stable he almost ran into another early riser, a girl in a velvet beret who was just leading a dapple grey mare out into the courtyard. The girl rubbed her face and yawned, leaning against her horse’s withers.

‘Oh my,’ she murmured, passing the messenger, ‘I’ll probably fall asleep on my horse … I’ll just flake out … Auuh …’

‘The cold’ll wake you up when you give your mare free rein,’ said Aplegatt courteously, pulling his saddle off the rack. ‘Godspeed, miss.’

The girl turned and looked at him, as though she had only then noticed him. Her eyes were large and as green as emeralds. Aplegatt threw the saddlecloth over his horse.

‘I wished you a safe journey,’ he said. He wasn’t usually talkative or effusive but now he felt the need to talk to someone, even if this someone was just a sleepy teenager. Perhaps it was those long days of solitude on the road, or possibly that the girl reminded him a little of his middle daughter.

‘May the gods protect you,’ he added, ‘from accidents and foul weather. There are but two of you, and womenfolk at that … And times are ill at present. Danger lurks everywhere on the highways.’

The girl opened her green eyes wider. The messenger felt his spine go cold, and a shudder passed through him.

‘Danger …’ the girl said suddenly, in a strange, altered voice. ‘Danger comes silently. You will not hear it when it swoops down on grey feathers. I had a dream. The sand … The sand was hot from the sun.’

‘What?’ Aplegatt froze with the saddle pressed against his belly. ‘What say you, miss? What sand?’

The girl shuddered violently and rubbed her face. The dapple grey mare shook its head.

‘Ciri!’ shouted the black-haired woman sharply from the courtyard, adjusting the girth on her black stallion. ‘Hurry up!’

The girl yawned, looked at Aplegatt and blinked, appearing surprised by his presence in the stable. The messenger said nothing.

‘Ciri,’ repeated the woman, ‘have you fallen asleep in there?’

‘I’m coming, Madam Yennefer.’

By the time Aplegatt had finally saddled his horse and led it out into the courtyard there was no sign of either woman or girl. A cock crowed long and hoarsely, a dog barked, and a cuckoo called from among the trees. The messenger leapt into the saddle. He suddenly recalled the sleepy girl’s green eyes and her strange words. Danger comes silently? Grey feathers? Hot sand? The maid was probably not right in the head, he thought. You come across a lot like that these days; deranged girls spoiled by vagabonds or other ne’er-do-wells in these times of war … Yes, definitely deranged. Or possibly only sleepy, torn from her slumbers, not yet fully awake. It’s amazing the poppycock people come out with when they’re roaming around at dawn, still caught between sleep and wakefulness …

A second shudder passed through him, and he felt a pain between his shoulder blades. He massaged his back with a fist.

Weak at the knees, he spurred his horse on as soon as he was back on the Maribor road, and rode away at a gallop. Time was running out.

The messenger did not rest for long in Maribor – not a day had passed before the wind was whistling in his ears again. His new horse, a roan gelding from the Maribor stable, ran hard, head forward and its tail flowing behind. Roadside willows flashed past. The satchel with the diplomatic mail pressed against Aplegatt’s chest. His arse ached.

‘Oi! I hope you break your neck, you blasted gadabout!’ yelled a carter in his wake, pulling in the halter of his team, startled by the galloping roan flashing by. ‘See how he runs, like devils were licking his heels! Ride on, giddy-head, ride; you won’t outrun Death himself!’

Aplegatt wiped an eye, which was watering from the speed.

The day before he had given King Foltest a letter, and then recited King Demavend’s secret message.

‘Demavend to Foltest. All is prepared in Dol Angra. The disguised forces await the order. Estimated date: the second night after the July new moon. The boats are to beach on the far shore two days later.’

Flocks of crows flew over the highway, cawing loudly. They flew east, towards Mahakam and Dol Angra, towards Vengerberg. As he rode, the messenger silently repeated the confidential message the king of Temeria had entrusted to him for the king of Aedirn.

‘Foltest to Demavend. Firstly: let us call off the campaign. The windbags have called a council. They are going to meet and debate on the Isle of Thanedd. This council may change much. Secondly: the search for the Lion Cub can be called off. It is confirmed. The Lion Cub is dead.’

Aplegatt spurred on his horse. Time was running out.

The narrow forest track was blocked with wagons. Aplegatt slowed down and trotted unhurriedly up to the last wagon in the long column. He saw he could not force his way through the obstruction, but nor could he think about heading back; too much time would be lost. Venturing into the boggy thicket and riding around the obstruction was not an attractive alternative either, particularly since darkness was falling.

‘What’s going on?’ he asked the drivers of the last wagon in the column. They were two old men, one of whom seemed to be dozing and the other showing no signs of life. ‘An attack? Scoia’tael? Speak up! I’m in a hurry …’

Before either of the two old men had a chance to answer, screams could be heard from the head of the column, hidden amongst the trees. Drivers leapt onto their wagons, lashing their horses and oxen to the accompaniment of choice oaths. The column moved off ponderously. The dozing old man awoke, moved his chin, clucked at his mules and flicked the reins across their rumps. The moribund old man came to life too, drew his straw hat back from his eyes and looked at Aplegatt.

‘Mark him,’ he said. ‘A hasty one. Well, laddie, your luck’s in. You’ve joined the company right on time.’

‘Aye,’ said the other old man, motioning with his chin and urging the mules forward. ‘You are timely. Had you come at noon, you’d have come to a stop like us and waited for a clear passage. We’re all in a hurry, but we had to wait. How can you ride on, when the way is closed?’

‘The way closed? Why so?’

‘There’s a cruel man-eater in these parts, laddie. He fell on a knight riding along the road with nowt but a boy for company. They say the monster rent the knight’s head right off – helmet and all – and spilt his horse’s gizzards. The boy made good his escape and said it was a fell beast, that the road was crimson with gore—’

‘What kind of monster is it?’ asked Aplegatt, reining in his horse in order to continue talking to the wagoners as they drove on. ‘A dragon?’

‘Nay, it’s no dragon,’ said the one in the straw hat. ‘’Tis said to be a manticore, or some such. The boy said ’tis a flying beast, awful huge. And vicious! We reckoned he would devour the knight and fly away, but no! They say he settled on the road, the whoreson, and was sat there, hissing and baring its fangs … Yea, and the road all stopped up like a corked-up flagon, for whoever drove up first and saw the fiend left his wagon and hastened away. Now the wagons are backed up for a third of a league, and all around, as you see, laddie, thicket and bog. There’s no riding around or turning back. So here we stood …’

‘Such a host!’ snorted the horseman. ‘And they were standing by like dolts when they ought to’ve seized axe and spear to drive the beast from the road, or slaughter it.’

‘Aye, a few tried,’ said the old wagoner, driving on his mules, for the column was now moving more quickly. ‘Three dwarves from the merchants’ guard and, with them, four recruits who were heading to the stronghold in Carreras to join the army. The monster carved up the dwarves horribly, and the recruits –’

‘– bolted,’ finished the other old man, after which he spat rapturously. The gob flew a long way ahead of him, expertly falling into the space between the mules’ rumps. ‘Bolted, after barely setting their eyes on the manticore. One of them shat his britches, I hear. Oh, look, look, laddie. That’s him! Yonder!’

‘What are you blathering on about?’ asked Aplegatt, somewhat annoyed. ‘You’re pointing out that shitty arse ? I’m not interested—’

‘Nay! The monster! The monster’s corpse! They’re lifting it onto a wagon! D’you see?’

Aplegatt stood in his stirrups. In spite of the gathering darkness and the crowd of onlookers he saw the great tawny body being lifted up by soldiers. The monster’s bat-like wings and scorpion tail dragged inertly along the ground. Cheering, the soldiers lifted the corpse higher and heaved it onto a wagon. The horses harnessed to it, clearly disturbed by the stench of the carcass and the blood, neighed and tugged at the shaft.

‘Move along!’ the sergeant shouted at the old men. ‘Keep moving! Don’t block the road!’

The greybeard drove his mules on, the wagon bouncing over the rutted road. Aplegatt, urging on his horse with his heel, drew alongside.

‘Looks like the soldiers have put paid to the beast.’

‘Not a bit of it,’ rejoined the old man. ‘When the soldiers arrived, all they did was yell and order people around. “Stand still! Move on!” and all the rest of it. They were in no haste to deal with the monster. They sent for a witcher.’

‘A witcher?’

‘Aye,’ confirmed the second old man. ‘Someone recalled he’d seen a witcher in the village, and they sent for him. A while later he rode past us. His hair was white, his countenance fearful to behold, and he bore a cruel blade. Not an hour had passed than someone called from the front that the road would soon be clear, for the witcher had dispatched the beast. So at last we set off; which was just about when you turned up, laddie.’

‘Ah,’ said Aplegatt absentmindedly. ‘All these years I’ve been scouring these roads and never met a witcher. Did anyone see him defeat the monster?’

‘I saw it!’ called a boy with a shock of tousled hair, trotting up on the other side of the wagon. He was riding bareback, steering a skinny, dapple grey nag using a halter. ‘I saw it all! I was with the soldiers, right at the front!’

‘Look at him, snot-nosed kid,’ said the old man driving the wagon. ‘Milk not dried on his face, and see how he mouths off. Looking for a slap?’

‘Leave him, father,’ interrupted Aplegatt. ‘We’ll reach the crossroads soon and I’m riding to Carreras, so first I’d like to know how the witcher got on. Talk, boy.’

‘It was like this,’ he began quickly, still trotting alongside the wagon. ‘That witcher comes up to the officer. He says his name’s Geralt. The officer says it’s all the same to him, and it’d be better if he made a start. Shows him where the monster is. The witcher moves closer and looks on. The monster’s about five furlongs or more away, but he just glances at it and says at once it’s an uncommon great manticore and he’ll kill it if they give him two hundred crowns.’

‘Two hundred crowns?’ choked the other old man. ‘Had he gone cuckoo?’

‘The officer says the same, only his words were riper. So the witcher says that’s how much it will cost and it’s all the same to him; the monster can stay on the road till Judgement Day. The officer says he won’t pay that much and he’ll wait till the beast flies off by itself. The witcher says it won’t because it’s hungry and pissed off. And if it flies off, it’ll be back soon because that’s its hunting terri–terri– territor—’

‘You whippersnapper, don’t talk nonsense!’ said the old man driving the cart, losing his temper, unsuccessfully trying to clear his nose into the fingers he was holding the reins with. ‘Just tell us what happened!’

‘I am telling you! The witcher goes, “The monster won’t fly away, he’ll spend the entire night eating the dead knight, nice and slow, because the knight’s in armour and it’s hard to pick out the meat.” So some merchants step up and try making a deal with the witcher, by hook or by crook, that they’ll organise a whip-round and give him five score crowns. The witcher says that beast’s a manticore and is very dangerous, and they can shove their hundred crowns up their arses, he won’t risk his neck for it. So the officer gets pissed off and says tough luck, it’s a witcher’s fate to risk his neck, and that a witcher is perfectly suited to it, like an arse is perfectly suited to shitting. But I can see the merchants get afeared the witcher would get angry and head off, because they say they’ll pay seven score and ten. So then the witcher gets his sword out and heads off down the road towards where the beast’s sitting. And the officer makes a mark behind him to drive away magic, spits on the ground and says he doesn’t know why the earth bears such hellish abominations. One of the merchants says that if the army drove away monsters from roads instead of chasing elves through forests, witchers wouldn’t be needed and that—’

‘Don’t drivel,’ interrupted the old man. ‘Just say what you saw.’

‘I saw,’ boasted the boy, ‘the witcher’s horse, a chestnut mare with a white blaze.’

‘Blow the mare! Did you see the witcher kill the monster?’

‘Err …’ stammered the boy. ‘No I didn’t … I got pushed to the back. Everybody was shouting and the horses were startled, when—’

‘Just what I said,’ declared the old man contemptuously. ‘He didn’t see shite, snotty-nosed kid.’

‘But I saw the witcher coming back!’ said the boy, indignantly. ‘And the officer, who saw it all, he was as pale as a ghost and said quietly to his men it was magic spells or elven tricks and that a normal man couldn’t wield a sword that quickly … While the witcher ups and takes the money from the merchants, mounts his mare and rides off.’

‘Hmm,’ murmured Aplegatt. ‘Which way was he headed? Along the road to Carreras? If so, I might catch him up, just to have a look at him …’

‘No,’ said the boy. ‘He took the road to Dorian from the crossroads. He was in a hurry.’

The Witcher seldom dreamed at all, and he never remembered those rare dreams on waking. Not even when they were nightmares – and they were usually nightmares.

This time it was also a nightmare, but at least the Witcher remembered some of it. A distinct, clear image had suddenly emerged from a swirling vortex of unclear but disturbing shapes, of strange but foreboding scenes and incomprehensible but sinister words and sounds. It was Ciri, but not as he remembered her from Kaer Morhen. Her flaxen hair, flowing behind her as she galloped, was longer – as it had been when they first met, in Brokilon. When she rode by he wanted to shout but no words came. He wanted to run after her, but it was as if he were stuck in setting pitch to halfway up his thighs. And Ciri seemed not to see him and galloped on, into the night, between misshapen alders and willows waving their boughs as if they were alive. He saw she was being pursued. That a black horse was galloping in her tracks, and on it a rider in black armour, wearing a helmet decorated with the wings of a bird of prey.

He couldn’t move, he couldn’t shout. He could only watch as the winged knight chased Ciri, caught her hair, pulled her from the saddle and galloped on, dragging her behind him. He could only watch Ciri’s face contort with pain, watch her mouth twist into a soundless cry. Awake! he ordered himself, unable to bear the nightmare. Awake! Awake at once!

He awoke.

He lay motionless for a long while, recalling the dream. Then he rose. He drew a pouch from beneath his pillow and quickly counted out some ten-crown coins. One hundred and fifty for yesterday’s manticore. Fifty for the fogler he had been commissioned to kill by the headman of a village near Carreras. And fifty for the werewolf some settlers from Burdorff had driven out of hiding for him.

Fifty for a werewolf. That was plenty, for the work had been easy. The werewolf hadn’t even fought back. Driven into a cave from which there was no escape, it had knelt down and waited for the sword to fall. The Witcher had felt sorry for it.

But he needed the money.

Before an hour had passed he was ambling down the streets of the town of Dorian, looking for a familiar lane and sign.

The wording on the sign read: ‘Codringher and Fenn, legal consultation and services’. But Geralt knew only too well that Codringher and Fenn’s trade had little in common with the law, while the partners themselves had a host of reasons to avoid any kind of contact either with the law or its enforcers. He also seriously doubted if any of the clients who showed up in their chambers knew what the word ‘consultation’ meant.

There was no entrance on the ground floor of the small building; there was only a securely bolted door, probably leading to a coach house or a stable. In order to reach the door one had to venture around the back of the building, enter a muddy courtyard full of ducks and chickens and, from there, walk up some steps before proceeding down a narrow gallery and along a cramped, dark corridor. Only then did one find oneself before a solid, studded mahogany door, equipped with a large brass knocker in the form of a lion’s head.

Geralt knocked, and then quickly withdrew. He knew the mechanism mounted in the door could shoot twenty-inch iron spikes through holes hidden among the studs. In theory the spikes were only released if someone tried to tamper with the lock, or if Codringher or Fenn pressed the trigger mechanism, but Geralt had discovered, many times, that all mechanisms are unreliable. They only worked when they ought not to work, and vice versa.

There was sure to be a device in the door – probably magic – for identifying guests. Having knocked, as today, no voice from within ever plied him with questions or demanded that he speak. The door opened and Codringher was standing there. Always Codringher, never Fenn.

‘Welcome, Geralt,’ said Codringher. ‘Enter. You don’t need to flatten yourself against the doorframe, I’ve dismantled the security device. Some part of it broke a few days ago. It went off quite out of the blue and drilled a few holes in a hawker. Come right in. Do you have a case for me?’

‘No,’ said the Witcher, entering the large, gloomy anteroom which, as usual, smelled faintly of cat. ‘Not for you. For Fenn.’

Codringher cackled loudly, confirming the Witcher’s suspicions that Fenn was an utterly mythical figure who served to pull the wool over the eyes of provosts, bailiffs, tax collectors and any other individuals Codringher detested.

They entered the office, where it was lighter because it was the topmost room and the solidly barred windows enjoyed the sun for most of the day. Geralt sat in the chair reserved for clients. Opposite, in an upholstered armchair behind an oaken desk, lounged Codringher; a man who introduced himself as a ‘lawyer’, a man for whom nothing was impossible. If anyone had difficulties, troubles, problems, they went to Codringher. And would quickly be handed proof of his business partner’s dishonesty and malpractice. Or he would receive credit without securities or guarantees. Or find himself the only one, from a long list of creditors, to exact payment from a business which had declared itself bankrupt. He would receive his inheritance even though his rich uncle had threatened he wouldn’t leave them a farthing. He would win an inheritance case when even the most determined relatives unexpectedly withdrew their claims. His son would leave the

A head of gold is essential, Aplegatt instructed the young messengers, since in the flat leather pouch strapped to his chest beneath his clothing the messenger only carries news of less vital importance, which could without fear be entrusted to treacherous paper or manuscript. The really important, secret tidings – those on which a great deal depended – must be committed to memory by the messenger and only repeated to the intended recipient. Word for word; and at times those words are far from simple. Difficult to pronounce, let alone remember. In order to memorise them and not make a mistake when they are recounted, one has to have a truly golden head.

And the benefits of an arse of iron, oh, every messenger will swiftly learn those for himself. When the moment comes for him to spend three days and nights in the saddle, riding a hundred or even two hundred miles along roads or sometimes, when necessary, trackless terrain, then it is needed. No, of course you don’t sit in the saddle without respite; sometimes you dismount and rest. For a man can bear a great deal, but a horse less. However, when it’s time to get back in the saddle after resting, it’s as though your arse were shouting, ‘Help! Murder!’

‘But who needs mounted messengers now, Master Aplegatt?’ young people would occasionally ask in astonishment. ‘Take Vengerberg to Vizima; no one could knock that off in less than four – or even five – days, even on the swiftest steed. But how long does a sorcerer from Vengerberg need to send news to a sorcerer from Vizima? Half an hour, or not even that. A messenger’s horse may go lame, but a sorcerer’s message always arrives. It never loses its way. It never arrives late or gets lost. What’s the point of messengers, if there are sorcerers everywhere, at every kingly court? Messengers are no longer necessary, Master Aplegatt.’

For some time Aplegatt had also been thinking he was no longer of any use to anyone. He was thirty-six and small but strong and wiry, wasn’t afraid of hard work and had – naturally – a head of gold. He could have found other work to support himself and his wife, to put a bit of money by for the dowries of his two as yet unmarried daughters and to continue helping the married one whose husband, the sad loser, was always unlucky in his business ventures. But Aplegatt couldn’t and didn’t want to imagine any other job. He was a royal mounted messenger and that was that.

And then suddenly, after a long period of being forgotten and humiliatingly idle, Aplegatt was once again needed. And the highways and forest tracks once again echoed to the sound of hooves. Just like the old days, messengers began to travel the land bearing news from town to town.

Aplegatt knew why. He saw a lot and heard even more. It was expected that he would immediately erase each message from his memory once it had been given, that he would forget it so as to be unable to recall it even under torture. But Aplegatt remembered. He knew why kings had suddenly stopped communicating with the help of magic and sorcerers. The news that the messengers were carrying was meant to remain a secret from them. Kings had suddenly stopped trusting sorcerers; stopped confiding their secrets in them.

Aplegatt didn’t know what had caused this sudden cooling off in the friendship between kings and sorcerers and wasn’t overly concerned about it. He regarded both kings and magic-users as incomprehensible creatures, unpredictable in their deeds – particularly when times were becoming hard. And the fact that times were now hard could not be ignored, not if one travelled across the land from castle to castle, from town to town, from kingdom to kingdom.

There were plenty of troops on the roads. With every step one came across an infantry or cavalry column, and every commander you met was edgy, nervous, curt and as self-important as if the fate of the entire world rested on him alone. The cities and castles were also full of armed men, and a feverish bustle went on there, day and night. The usually invisible burgraves and castellans now ceaselessly rushed along walls and through courtyards, angry as wasps before a storm, yelling, swearing and issuing orders and kicks. Day and night, lumbering columns of laden wagons rolled towards strongholds and garrisons, passing carts on their way back, moving quickly, unburdened and empty. Herds of frisky three-year-old mounts taken straight out of stables kicked dust up on the roads. Ponies not accustomed to bits nor armed riders cheerfully enjoyed their last days of freedom, giving stable boys plenty of extra work and other road users no small trouble.

To put it briefly, war hung in the hot, still air.

Aplegatt stood up in his stirrups and looked around. Down at the foot of the hill a river sparkled, meandering sharply among meadows and clusters of trees. Forests stretched out beyond it, to the south. The messenger urged his horse on. Time was running out.

He’d been on the road for two days. The royal order and mail had caught up with him in Hagge, where he was resting after returning from Tretogor. He had left the stronghold by night, galloping along the highway following the left bank of the Pontar, crossed the border with Temeria before dawn, and now, at noon of the following day, was already at the bank of the Ismena. Had King Foltest been in Vizima, Aplegatt would have delivered him the message that night. Unfortunately, the king was not in the capital; he was residing in the south of the country, in Maribor, almost two hundred miles from Vizima. Aplegatt knew this, so in the region of the White Bridge he left the westward-leading road and rode through woodland towards Ellander. He was taking a risk. The Scoia’tael* continued to roam the forests, and woe betide anyone who fell into their hands or came within arrowshot. But a royal messenger had to take risks. Such was his duty.

He crossed the river without difficulty – it hadn’t rained since June and the Ismena’s waters had fallen considerably. Keeping to the edge of the forest, he reached the track leading south-east from Vizima, towards the dwarven foundries, forges and settlements in the Mahakam Mountains. There were plenty of carts along the track, often being overtaken by small mounted units. Aplegatt sighed in relief. Where there were lots of humans, there weren’t any Scoia’tael. The campaign against the guerrilla elves had endured in Temeria for a year and, being harried in the forests, the Scoia’tael commandos had divided up into smaller groups. These smaller groups kept well away from well-used roads and didn’t set ambushes on them.

Before nightfall he was already on the western border of the duchy of Ellander, at a crossroads near the village of Zavada. From here he had a straight and safe road to Maribor: forty-two miles of hard, well-frequented forest track, and there was an inn at the crossroads. He decided to rest his horse and himself there. Were he to set off at daybreak he knew that, even without pushing his mount too hard, he would see the silver and black pennants on the red roofs of Maribor Castle’s towers before sundown.

He unsaddled his mare and groomed her himself, sending the stable boy away. He was a royal messenger, and a royal messenger never permits anyone to touch his horse. He ate a goodly portion of scrambled eggs with sausage and a quarter of a loaf of rye bread, washed down with a quart of ale. He listened to the gossip. Of various kinds. Travellers from every corner of the world were dining at the inn.

Aplegatt learned there’d been more trouble in Dol Angra; a troop of Lyrian cavalry had once again clashed with a mounted Nilfgaardian unit. Meve, the queen of Lyria, had loudly accused Nilfgaard of provocation – again – and called for help from King Demavend of Aedirn. Tretogor had seen the public execution of a Redanian baron who had secretly allied himself with emissaries of the Nilfgaardian emperor, Emhyr. In Kaedwen, Scoia’tael commandos, amassed into a large unit, had orchestrated a massacre in Fort Leyda. To avenge the massacre, the people of Ard Carraigh had organised a pogrom, murdering almost four hundred non-humans residing in the capital.

Meanwhile the merchants travelling from the south described the grief and mourning among the Cintran emigrants gathered in Temeria, under the standard of Marshal Vissegerd. The dreadful news of the death of Princess Cirilla, the Lion Cub, the last of the bloodline of Queen Calanthe, had been confirmed.

Some even darker, more foreboding gossip was told. That in several villages in the region of Aldersberg cows had suddenly begun to squirt blood from their udders while being milked, and at dawn the Virgin Bane, harbinger of terrible destruction, had been seen in the fog. The Wild Hunt, a spectral army galloping across the firmament, had appeared in Brugge, in the region of Brokilon Forest, the forbidden kingdom of the forest dryads; and the Wild Hunt, as is generally known, always heralds war. And a spectral ship had been spotted off Cape Bremervoord with a ghoul on board: a black knight in a helmet adorned with the wings of a bird of prey …

The messenger stopped listening; he was too tired. He went to the common sleeping chamber, dropped onto his pallet and fell fast asleep.

He arose at daybreak and was a little surprised as he entered the courtyard – he was not the first person preparing to leave, which was unusual. A black gelding stood saddled by the well, while nearby a woman in male clothing was washing her hands in the trough. Hearing Aplegatt’s footsteps she turned, gathered her luxuriant black hair in her wet hands, and tossed it back. The messenger bowed. The woman gave a faint nod.

As he entered the stable he almost ran into another early riser, a girl in a velvet beret who was just leading a dapple grey mare out into the courtyard. The girl rubbed her face and yawned, leaning against her horse’s withers.

‘Oh my,’ she murmured, passing the messenger, ‘I’ll probably fall asleep on my horse … I’ll just flake out … Auuh …’

‘The cold’ll wake you up when you give your mare free rein,’ said Aplegatt courteously, pulling his saddle off the rack. ‘Godspeed, miss.’

The girl turned and looked at him, as though she had only then noticed him. Her eyes were large and as green as emeralds. Aplegatt threw the saddlecloth over his horse.

‘I wished you a safe journey,’ he said. He wasn’t usually talkative or effusive but now he felt the need to talk to someone, even if this someone was just a sleepy teenager. Perhaps it was those long days of solitude on the road, or possibly that the girl reminded him a little of his middle daughter.

‘May the gods protect you,’ he added, ‘from accidents and foul weather. There are but two of you, and womenfolk at that … And times are ill at present. Danger lurks everywhere on the highways.’

The girl opened her green eyes wider. The messenger felt his spine go cold, and a shudder passed through him.

‘Danger …’ the girl said suddenly, in a strange, altered voice. ‘Danger comes silently. You will not hear it when it swoops down on grey feathers. I had a dream. The sand … The sand was hot from the sun.’

‘What?’ Aplegatt froze with the saddle pressed against his belly. ‘What say you, miss? What sand?’

The girl shuddered violently and rubbed her face. The dapple grey mare shook its head.

‘Ciri!’ shouted the black-haired woman sharply from the courtyard, adjusting the girth on her black stallion. ‘Hurry up!’

The girl yawned, looked at Aplegatt and blinked, appearing surprised by his presence in the stable. The messenger said nothing.

‘Ciri,’ repeated the woman, ‘have you fallen asleep in there?’

‘I’m coming, Madam Yennefer.’

By the time Aplegatt had finally saddled his horse and led it out into the courtyard there was no sign of either woman or girl. A cock crowed long and hoarsely, a dog barked, and a cuckoo called from among the trees. The messenger leapt into the saddle. He suddenly recalled the sleepy girl’s green eyes and her strange words. Danger comes silently? Grey feathers? Hot sand? The maid was probably not right in the head, he thought. You come across a lot like that these days; deranged girls spoiled by vagabonds or other ne’er-do-wells in these times of war … Yes, definitely deranged. Or possibly only sleepy, torn from her slumbers, not yet fully awake. It’s amazing the poppycock people come out with when they’re roaming around at dawn, still caught between sleep and wakefulness …

A second shudder passed through him, and he felt a pain between his shoulder blades. He massaged his back with a fist.

Weak at the knees, he spurred his horse on as soon as he was back on the Maribor road, and rode away at a gallop. Time was running out.

The messenger did not rest for long in Maribor – not a day had passed before the wind was whistling in his ears again. His new horse, a roan gelding from the Maribor stable, ran hard, head forward and its tail flowing behind. Roadside willows flashed past. The satchel with the diplomatic mail pressed against Aplegatt’s chest. His arse ached.

‘Oi! I hope you break your neck, you blasted gadabout!’ yelled a carter in his wake, pulling in the halter of his team, startled by the galloping roan flashing by. ‘See how he runs, like devils were licking his heels! Ride on, giddy-head, ride; you won’t outrun Death himself!’

Aplegatt wiped an eye, which was watering from the speed.

The day before he had given King Foltest a letter, and then recited King Demavend’s secret message.

‘Demavend to Foltest. All is prepared in Dol Angra. The disguised forces await the order. Estimated date: the second night after the July new moon. The boats are to beach on the far shore two days later.’

Flocks of crows flew over the highway, cawing loudly. They flew east, towards Mahakam and Dol Angra, towards Vengerberg. As he rode, the messenger silently repeated the confidential message the king of Temeria had entrusted to him for the king of Aedirn.

‘Foltest to Demavend. Firstly: let us call off the campaign. The windbags have called a council. They are going to meet and debate on the Isle of Thanedd. This council may change much. Secondly: the search for the Lion Cub can be called off. It is confirmed. The Lion Cub is dead.’

Aplegatt spurred on his horse. Time was running out.

The narrow forest track was blocked with wagons. Aplegatt slowed down and trotted unhurriedly up to the last wagon in the long column. He saw he could not force his way through the obstruction, but nor could he think about heading back; too much time would be lost. Venturing into the boggy thicket and riding around the obstruction was not an attractive alternative either, particularly since darkness was falling.

‘What’s going on?’ he asked the drivers of the last wagon in the column. They were two old men, one of whom seemed to be dozing and the other showing no signs of life. ‘An attack? Scoia’tael? Speak up! I’m in a hurry …’

Before either of the two old men had a chance to answer, screams could be heard from the head of the column, hidden amongst the trees. Drivers leapt onto their wagons, lashing their horses and oxen to the accompaniment of choice oaths. The column moved off ponderously. The dozing old man awoke, moved his chin, clucked at his mules and flicked the reins across their rumps. The moribund old man came to life too, drew his straw hat back from his eyes and looked at Aplegatt.

‘Mark him,’ he said. ‘A hasty one. Well, laddie, your luck’s in. You’ve joined the company right on time.’

‘Aye,’ said the other old man, motioning with his chin and urging the mules forward. ‘You are timely. Had you come at noon, you’d have come to a stop like us and waited for a clear passage. We’re all in a hurry, but we had to wait. How can you ride on, when the way is closed?’

‘The way closed? Why so?’

‘There’s a cruel man-eater in these parts, laddie. He fell on a knight riding along the road with nowt but a boy for company. They say the monster rent the knight’s head right off – helmet and all – and spilt his horse’s gizzards. The boy made good his escape and said it was a fell beast, that the road was crimson with gore—’

‘What kind of monster is it?’ asked Aplegatt, reining in his horse in order to continue talking to the wagoners as they drove on. ‘A dragon?’

‘Nay, it’s no dragon,’ said the one in the straw hat. ‘’Tis said to be a manticore, or some such. The boy said ’tis a flying beast, awful huge. And vicious! We reckoned he would devour the knight and fly away, but no! They say he settled on the road, the whoreson, and was sat there, hissing and baring its fangs … Yea, and the road all stopped up like a corked-up flagon, for whoever drove up first and saw the fiend left his wagon and hastened away. Now the wagons are backed up for a third of a league, and all around, as you see, laddie, thicket and bog. There’s no riding around or turning back. So here we stood …’

‘Such a host!’ snorted the horseman. ‘And they were standing by like dolts when they ought to’ve seized axe and spear to drive the beast from the road, or slaughter it.’

‘Aye, a few tried,’ said the old wagoner, driving on his mules, for the column was now moving more quickly. ‘Three dwarves from the merchants’ guard and, with them, four recruits who were heading to the stronghold in Carreras to join the army. The monster carved up the dwarves horribly, and the recruits –’

‘– bolted,’ finished the other old man, after which he spat rapturously. The gob flew a long way ahead of him, expertly falling into the space between the mules’ rumps. ‘Bolted, after barely setting their eyes on the manticore. One of them shat his britches, I hear. Oh, look, look, laddie. That’s him! Yonder!’

‘What are you blathering on about?’ asked Aplegatt, somewhat annoyed. ‘You’re pointing out that shitty arse ? I’m not interested—’

‘Nay! The monster! The monster’s corpse! They’re lifting it onto a wagon! D’you see?’

Aplegatt stood in his stirrups. In spite of the gathering darkness and the crowd of onlookers he saw the great tawny body being lifted up by soldiers. The monster’s bat-like wings and scorpion tail dragged inertly along the ground. Cheering, the soldiers lifted the corpse higher and heaved it onto a wagon. The horses harnessed to it, clearly disturbed by the stench of the carcass and the blood, neighed and tugged at the shaft.

‘Move along!’ the sergeant shouted at the old men. ‘Keep moving! Don’t block the road!’

The greybeard drove his mules on, the wagon bouncing over the rutted road. Aplegatt, urging on his horse with his heel, drew alongside.

‘Looks like the soldiers have put paid to the beast.’

‘Not a bit of it,’ rejoined the old man. ‘When the soldiers arrived, all they did was yell and order people around. “Stand still! Move on!” and all the rest of it. They were in no haste to deal with the monster. They sent for a witcher.’

‘A witcher?’

‘Aye,’ confirmed the second old man. ‘Someone recalled he’d seen a witcher in the village, and they sent for him. A while later he rode past us. His hair was white, his countenance fearful to behold, and he bore a cruel blade. Not an hour had passed than someone called from the front that the road would soon be clear, for the witcher had dispatched the beast. So at last we set off; which was just about when you turned up, laddie.’

‘Ah,’ said Aplegatt absentmindedly. ‘All these years I’ve been scouring these roads and never met a witcher. Did anyone see him defeat the monster?’

‘I saw it!’ called a boy with a shock of tousled hair, trotting up on the other side of the wagon. He was riding bareback, steering a skinny, dapple grey nag using a halter. ‘I saw it all! I was with the soldiers, right at the front!’

‘Look at him, snot-nosed kid,’ said the old man driving the wagon. ‘Milk not dried on his face, and see how he mouths off. Looking for a slap?’

‘Leave him, father,’ interrupted Aplegatt. ‘We’ll reach the crossroads soon and I’m riding to Carreras, so first I’d like to know how the witcher got on. Talk, boy.’

‘It was like this,’ he began quickly, still trotting alongside the wagon. ‘That witcher comes up to the officer. He says his name’s Geralt. The officer says it’s all the same to him, and it’d be better if he made a start. Shows him where the monster is. The witcher moves closer and looks on. The monster’s about five furlongs or more away, but he just glances at it and says at once it’s an uncommon great manticore and he’ll kill it if they give him two hundred crowns.’

‘Two hundred crowns?’ choked the other old man. ‘Had he gone cuckoo?’

‘The officer says the same, only his words were riper. So the witcher says that’s how much it will cost and it’s all the same to him; the monster can stay on the road till Judgement Day. The officer says he won’t pay that much and he’ll wait till the beast flies off by itself. The witcher says it won’t because it’s hungry and pissed off. And if it flies off, it’ll be back soon because that’s its hunting terri–terri– territor—’

‘You whippersnapper, don’t talk nonsense!’ said the old man driving the cart, losing his temper, unsuccessfully trying to clear his nose into the fingers he was holding the reins with. ‘Just tell us what happened!’

‘I am telling you! The witcher goes, “The monster won’t fly away, he’ll spend the entire night eating the dead knight, nice and slow, because the knight’s in armour and it’s hard to pick out the meat.” So some merchants step up and try making a deal with the witcher, by hook or by crook, that they’ll organise a whip-round and give him five score crowns. The witcher says that beast’s a manticore and is very dangerous, and they can shove their hundred crowns up their arses, he won’t risk his neck for it. So the officer gets pissed off and says tough luck, it’s a witcher’s fate to risk his neck, and that a witcher is perfectly suited to it, like an arse is perfectly suited to shitting. But I can see the merchants get afeared the witcher would get angry and head off, because they say they’ll pay seven score and ten. So then the witcher gets his sword out and heads off down the road towards where the beast’s sitting. And the officer makes a mark behind him to drive away magic, spits on the ground and says he doesn’t know why the earth bears such hellish abominations. One of the merchants says that if the army drove away monsters from roads instead of chasing elves through forests, witchers wouldn’t be needed and that—’

‘Don’t drivel,’ interrupted the old man. ‘Just say what you saw.’

‘I saw,’ boasted the boy, ‘the witcher’s horse, a chestnut mare with a white blaze.’

‘Blow the mare! Did you see the witcher kill the monster?’

‘Err …’ stammered the boy. ‘No I didn’t … I got pushed to the back. Everybody was shouting and the horses were startled, when—’

‘Just what I said,’ declared the old man contemptuously. ‘He didn’t see shite, snotty-nosed kid.’

‘But I saw the witcher coming back!’ said the boy, indignantly. ‘And the officer, who saw it all, he was as pale as a ghost and said quietly to his men it was magic spells or elven tricks and that a normal man couldn’t wield a sword that quickly … While the witcher ups and takes the money from the merchants, mounts his mare and rides off.’

‘Hmm,’ murmured Aplegatt. ‘Which way was he headed? Along the road to Carreras? If so, I might catch him up, just to have a look at him …’

‘No,’ said the boy. ‘He took the road to Dorian from the crossroads. He was in a hurry.’

The Witcher seldom dreamed at all, and he never remembered those rare dreams on waking. Not even when they were nightmares – and they were usually nightmares.

This time it was also a nightmare, but at least the Witcher remembered some of it. A distinct, clear image had suddenly emerged from a swirling vortex of unclear but disturbing shapes, of strange but foreboding scenes and incomprehensible but sinister words and sounds. It was Ciri, but not as he remembered her from Kaer Morhen. Her flaxen hair, flowing behind her as she galloped, was longer – as it had been when they first met, in Brokilon. When she rode by he wanted to shout but no words came. He wanted to run after her, but it was as if he were stuck in setting pitch to halfway up his thighs. And Ciri seemed not to see him and galloped on, into the night, between misshapen alders and willows waving their boughs as if they were alive. He saw she was being pursued. That a black horse was galloping in her tracks, and on it a rider in black armour, wearing a helmet decorated with the wings of a bird of prey.

He couldn’t move, he couldn’t shout. He could only watch as the winged knight chased Ciri, caught her hair, pulled her from the saddle and galloped on, dragging her behind him. He could only watch Ciri’s face contort with pain, watch her mouth twist into a soundless cry. Awake! he ordered himself, unable to bear the nightmare. Awake! Awake at once!

He awoke.

He lay motionless for a long while, recalling the dream. Then he rose. He drew a pouch from beneath his pillow and quickly counted out some ten-crown coins. One hundred and fifty for yesterday’s manticore. Fifty for the fogler he had been commissioned to kill by the headman of a village near Carreras. And fifty for the werewolf some settlers from Burdorff had driven out of hiding for him.

Fifty for a werewolf. That was plenty, for the work had been easy. The werewolf hadn’t even fought back. Driven into a cave from which there was no escape, it had knelt down and waited for the sword to fall. The Witcher had felt sorry for it.

But he needed the money.

Before an hour had passed he was ambling down the streets of the town of Dorian, looking for a familiar lane and sign.

The wording on the sign read: ‘Codringher and Fenn, legal consultation and services’. But Geralt knew only too well that Codringher and Fenn’s trade had little in common with the law, while the partners themselves had a host of reasons to avoid any kind of contact either with the law or its enforcers. He also seriously doubted if any of the clients who showed up in their chambers knew what the word ‘consultation’ meant.

There was no entrance on the ground floor of the small building; there was only a securely bolted door, probably leading to a coach house or a stable. In order to reach the door one had to venture around the back of the building, enter a muddy courtyard full of ducks and chickens and, from there, walk up some steps before proceeding down a narrow gallery and along a cramped, dark corridor. Only then did one find oneself before a solid, studded mahogany door, equipped with a large brass knocker in the form of a lion’s head.

Geralt knocked, and then quickly withdrew. He knew the mechanism mounted in the door could shoot twenty-inch iron spikes through holes hidden among the studs. In theory the spikes were only released if someone tried to tamper with the lock, or if Codringher or Fenn pressed the trigger mechanism, but Geralt had discovered, many times, that all mechanisms are unreliable. They only worked when they ought not to work, and vice versa.

There was sure to be a device in the door – probably magic – for identifying guests. Having knocked, as today, no voice from within ever plied him with questions or demanded that he speak. The door opened and Codringher was standing there. Always Codringher, never Fenn.

‘Welcome, Geralt,’ said Codringher. ‘Enter. You don’t need to flatten yourself against the doorframe, I’ve dismantled the security device. Some part of it broke a few days ago. It went off quite out of the blue and drilled a few holes in a hawker. Come right in. Do you have a case for me?’

‘No,’ said the Witcher, entering the large, gloomy anteroom which, as usual, smelled faintly of cat. ‘Not for you. For Fenn.’

Codringher cackled loudly, confirming the Witcher’s suspicions that Fenn was an utterly mythical figure who served to pull the wool over the eyes of provosts, bailiffs, tax collectors and any other individuals Codringher detested.

They entered the office, where it was lighter because it was the topmost room and the solidly barred windows enjoyed the sun for most of the day. Geralt sat in the chair reserved for clients. Opposite, in an upholstered armchair behind an oaken desk, lounged Codringher; a man who introduced himself as a ‘lawyer’, a man for whom nothing was impossible. If anyone had difficulties, troubles, problems, they went to Codringher. And would quickly be handed proof of his business partner’s dishonesty and malpractice. Or he would receive credit without securities or guarantees. Or find himself the only one, from a long list of creditors, to exact payment from a business which had declared itself bankrupt. He would receive his inheritance even though his rich uncle had threatened he wouldn’t leave them a farthing. He would win an inheritance case when even the most determined relatives unexpectedly withdrew their claims. His son would leave the

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

The Time of Contempt

Andrzej Sapkowski

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved