- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

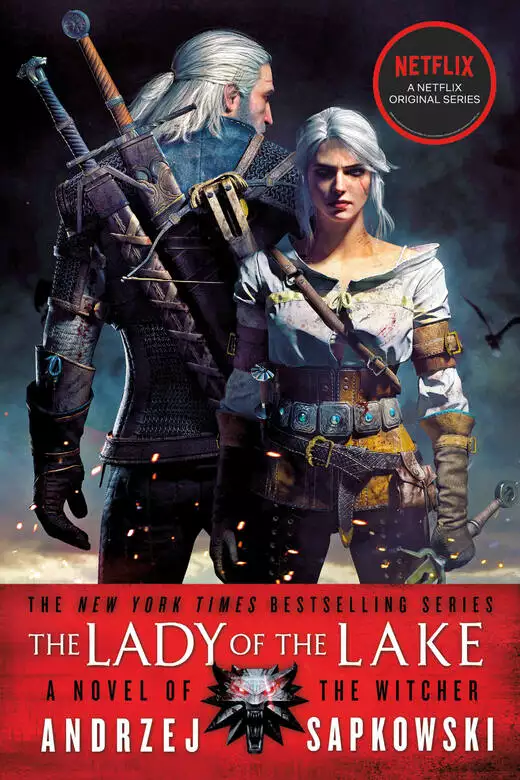

The Witcher returns in this action-packed sequel to The Tower of Swallows, in the New York Times bestselling series that inspired The Witcher video games.

After walking through the portal in the Tower of Swallows while narrowly escaping death, Ciri finds herself in a completely different world... an Elven world. She is trapped with no way out. Time does not seem to exist and there are no obvious borders or portals to cross back into her home world.

But this is Ciri, the child of prophecy, and she will not be defeated. She knows she must escape to finally rejoin the Witcher, Geralt, and his companions—and also to try to conquer her worst nightmare. Leo Bonhart, the man who chased, wounded and tortured Ciri, is still on her trail. And the world is still at war.

Witcher novels

Blood of Elves

The Time of Contempt

Baptism of Fire

The Tower of Swallows

Lady of the Lake

Witcher collections

The Last Wish

Sword of Destiny

Release date: March 14, 2017

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 560

Reader says this book is...: action-packed (1) emotionally riveting (1) entertaining story (1) epic storytelling (1) great world-building (1) high adventure (1) plot twists (1) rich setting(s) (1) satisfying ending (1) suspenseful (1) terrific writing (1) tragic (1) twists & turns (1) unputdownable (1)

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Lady of the Lake

Andrzej Sapkowski

Firstly, it lay right beside the mouth of the enchanted Cwm Pwcca valley, permanently veiled in mist and famed for witchcraft and magical phenomena.

Secondly, it was enough to look.

The lake was deep, a vivid, pure blue, just like polished sapphire. It was as smooth as a looking glass, so smooth the peaks of the Y Wyddfa massif gazing into it seemed more stunning reflected than in reality. A cold, bracing wind blew in from the lake and nothing disturbed the dignified silence, not even the splash of a fish or the cry of a water bird.

The knight shuddered in amazement. But instead of continuing to ride along the ridge he steered his horse towards the lake, as though lured by the magical power of the witchcraft slumbering down there, at the bottom, in the depths. The horse trod timidly across broken rocks, showing by a soft snorting that it also sensed the magical aura.

After descending to the very bottom of the valley, the knight dismounted. Leading his steed by the bridle, he neared the water’s edge, where faint ripples were playing among colourful pebbles.

He kneeled down, his chain mail rustling. Scaring away fry, fish as tiny and lively as needles, he scooped up water in his cupped hands. He drank slowly and gingerly, the ice-cold water numbing his lips and tongue and stinging his teeth.

As he stooped again, a sound, carried over the surface of the water, reached his ears. He raised his head. His horse snorted, as though confirming it had also heard.

He listened. No, it was no illusion. What he had heard was singing. A woman singing. Or, more likely, a girl.

The knight, like all knights, had been raised on stories of bards and tales of chivalry. And in them – nine times out of ten – girlish airs or wailing were bait, and the knights that followed them usually fell into traps. Often fatal ones.

But his curiosity got the better of him. The knight, after all, was only nineteen years old. He was very bold and very imprudent. He was famous for the first and known for the second.

He checked that his sword slid well in the scabbard, then tugged his horse and headed along the shore in the direction of the singing. He didn’t have to go far.

On the lakeside lay great, dark boulders – worn smooth to a shine. You might have said they were the playthings of giants carelessly tossed there or forgotten after a game. Some of the boulders lay in the lake, looming black beneath the crystalline water. Some of them protruded above the surface. Washed by the wavelets, they looked like the backs of leviathans. But most of them lay on the lakeside, covering the shore all the way to the treeline. Some of them were buried in the sand, only partly sticking out, leaving their true size to the imagination.

The singing that the knight could hear came from just behind the rocks near the shore. And the girl who was doing the singing was out of sight. He led his horse, holding it by the bit and nostrils to stop it whinnying or snorting.

The girl’s garments were spread on a perfectly flat boulder lying in the lake. She, naked and waist-deep in the water, was washing and singing the while. The knight didn’t recognise the words.

And no wonder.

The girl – he would have bet his life – was not flesh-and-blood. That was evident from her slim figure, the strange colour of her hair and her voice. He was certain that were she to turn around he would see huge, almond-shaped eyes. And were she to brush aside her ashen hair he would surely see pointed ears.

She was a dweller of Faërie. A spirit. One of the Tylwyth Têg. One of those creatures the Picts and Irish called Daoine Sidhe, the Folk of the Hill. One of those creatures the Saxons called elves.

The girl stopped singing for a moment, submerged herself up to the neck, snorted and swore very coarsely. It didn’t fool the knight, though. Fairies – as was widely known – could curse like humans. Oftentimes more filthily than stablemen. And very often the oath preceded a spiteful prank, for which fairies were famous. For example, swelling someone’s nose up to the size of a cucumber or shrinking another’s manhood down to the size of a broad bean.

Neither the first nor the second possibility appealed to the knight. He was on the point of a discreet withdrawal when the noise of hooves on the pebbles suddenly betrayed him. No, not his own steed, which – being held by the nostrils – was as calm and quiet as a mouse. He had been betrayed by the fairy’s horse, a black mare, which at first the knight hadn’t noticed among the rocks. Now the pitch-black animal churned up the pebbles with a hoof and neighed a greeting. The knight’s stallion tossed its head and neighed back politely. So loudly an echo sped across the water.

The fairy burst from the water, for a moment presenting herself to the knight in all her alluring splendour. She darted towards the rock where her clothing lay. But rather than seizing a blouse and covering up modestly, the she-elf grabbed a sword and drew it from its scabbard with a hiss, whirling it with admirable dexterity. It lasted but a short moment, after which she sank down, covering herself up to her nose in the water and extending her arm with the sword above the surface.

The knight shook off his stupefaction, released the reins and genuflected, kneeling on the wet sand. For he realised at once who was before him.

‘Hail,’ he mumbled, holding out his hands. ‘Great is the honour for me … Great is the accolade, O Lady of the Lake. I shall accept the sword …’

‘Could you get up from your knees and turn away?’ The fairy stuck her mouth above the water. ‘Perhaps you’d stop staring? And let me get dressed?’

He obeyed.

He heard her splash out of the water, rustle her clothes and swear softly as she pulled them over her wet body. He examined the black mare, its coat as smooth and lustrous as moleskin. It was certainly a horse of noble blood, certainly enchanted. And undoubtedly also a dweller of Faërie, like its owner.

‘You may turn around.’

‘Lady of the Lake—’

‘And introduce yourself.’

‘I am Galahad, of Caer Benic. A knight of King Arthur, the lord of Camelot, the ruler of the Summer Land, and also of Dumnonia, Dyfneint, Powys, Dyfedd …’

‘And Temeria?’ she interrupted. ‘Redania, Rivia, Aedirn? Nilfgaard? Do those names mean anything to you?’

‘No. I’ve never heard them.’

She shrugged. Apart from her sword she was holding her boots and her blouse, washed and wrung out.

‘I thought so. What day of the year is it today?’

‘It is,’ he opened his mouth, utterly astonished, ‘the second full moon after Beltane … Lady …’

‘Ciri,’ she said dully, wriggling her shoulders to allow her garments to lie better on her drying skin. She spoke strangely. Her eyes were large and green.

She involuntarily brushed her wet hair aside and the knight gasped unwittingly. Not just because her ear was normal, human, and in no way elven. Her cheek was disfigured by a large, ugly scar. She had been wounded. But could a fairy be wounded?

She noticed his look, narrowed her eyes and wrinkled her nose.

‘That’s right, it’s a scar!’ she repeated in her extraordinary accent. ‘Why do you look so scared? Is a scar such a strange thing for a knight to see? Is it so ugly?’

He removed his chainmail hood with both hands and brushed aside his hair.

‘Indeed it isn’t,’ he said, not without youthful pride, displaying a barely healed scar of his own, running from temple to jaw. ‘And only blemishes on one’s honour are ugly. I am Galahad, son of Lancelot du Lac and Elaine, daughter of King Pelles, lord of Caer Benic. That wound was dealt me by Breunis the Merciless, a base oppressor of maidens, before I felled him in a fair duel. In sooth, I am worthy of receiving that sword from your hands, O Lady of the Lake.’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘The sword. I’m ready to receive it.’

‘It’s my sword. I don’t let anyone touch it.’

‘But …’

‘But what?’

‘The Lady of the Lake always … always emerges from the waters and bestows a sword, doesn’t she?’

She said nothing for some time.

‘I get it,’ she finally said. ‘Well, every country has its own customs. I’m sorry, Galahad, or whatever your name is, but I’m clearly not the Lady I’m meant to be. I’m not giving away anything. And I won’t let anyone take anything from me. Just to make things clear.’

‘But,’ he ventured, ‘you must come from Faërie, don’t you, m’lady?’

‘I come …’ she said a moment later, and her green eyes seemed to be looking into an abyss of space and time. ‘I come from Rivia, from the city of the same name. From Loch Eskalott. I sailed here by boat. It was foggy. I couldn’t see the shore. I only heard the neighing. Of Kelpie … My mare, who followed me.

She spread out her wet blouse on a stone, and the knight gasped again. The blouse had been washed, but perfunctorily. Patches of blood were still visible.

‘The current brought me here,’ the girl began again, either not seeing what he had noticed or pretending not to. ‘The current and the spell of a unicorn … What’s this lake called?’

‘I don’t know,’ he confessed. ‘There are so many lakes in Gwynedd—’

‘In Gwynedd?’

‘Naturally. Those mountains are Y Wyddfa. If you keep them on your left hand and ride through the forests, after two days you’ll reach Dinas Dinlleu, and then on to Caer Dathal. And the river … The nearest river is …’

‘Never mind what the nearest river’s called. Do you have anything to eat, Galahad? I’m simply dying of hunger.’

‘Why are you watching me like that? Afraid I’ll disappear? That I’ll fly off with your hard tack and smoked sausage? Don’t worry. I got up to some mischief in my own world and confused destiny, so I shouldn’t show my face there for the moment. I’ll stay a while in yours. In a world where one searches the sky in vain for the Dragon or the Seven Goats. Where right now it’s the second full moon after Belleteyn, and Belleteyn is pronounced ‘Beltane’. Why are you staring at me like that, pray?’

‘I didn’t know fairies could eat.’

‘Fairies, sorceresses and she-elves. They all eat. And drink. And so on.’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘Never mind.’

The more intently he observed her, the more she lost her enchanting aura, and the more human and ordinary – common, even – she became. Though he knew she wasn’t, couldn’t be that. One didn’t encounter common wenches at the foot of Y Wyddfa, in the region of Cwm Pwcca, bathing naked in mountain lakes and washing bloodstained blouses. Never mind what the girl looked like, she couldn’t be an earthly being. In spite of that, Galahad was now gazing quite freely and without fear at her ashen hair, which, now it was dry, to his amazement gleamed grey. At her slender hands, petite nose and pale lips, at her masculine outfit of somewhat outlandish cut, sewn from delicate stuff of extremely dense weave. At her sword, of curious construction and ornamentation, but by no means resembling a ceremonial accoutrement. At her bare feet caked with the dried sand of the beach.

‘Just for clarity,’ she began, rubbing one foot against the other, ‘I’m not a she-elf. And as for being an enchantress, I mean a fairy … I’m a little unusual. I don’t think I’m one at all.’

‘I’m sorry, I really am.’

‘Why exactly?’

‘They say …’ he blushed and stammered. ‘They say that when fairies meet young men, they lead them to Elfland and there … Beneath a filbert bush, on a carpet of moss, they order them to render—’

‘I understand.’ She glanced at him quickly, then bit down hard on a sausage. ‘Regarding the land of Elves,’ she said, swallowing, ‘I fled from there some time ago and am in no hurry to return. Regarding, however, the rendering of services on mossy carpets … Truly, Galahad, you’ve happened upon the wrong Lady. All the same, I thank you kindly for your good intentions.’

‘M’lady! I did not wish to offend—’

‘You don’t have to apologise.’

‘Only because,’ he mumbled, ‘you’re enchantingly comely.’

‘Thank you, once again. But still, nothing’s going to happen.’

They were silent for a time. It was warm. The sun, standing at its zenith, warmed the stones pleasantly. A faint breeze ruffled the surface of the lake.

‘What does …’ Galahad began suddenly in a strangely enraptured voice. ‘What does the spear with the bloody blade mean? Why does the King with the lanced thigh suffer and what does it mean? What is the meaning of the maiden in white carrying a grail, a silver bowl—?’

‘And besides that,’ she interrupted him. ‘Are you feeling all right?’

‘I merely ask.’

‘And I merely don’t understand your question. Is it some previously agreed password? Some signal by which the initiated recognise each other? Kindly explain.’

‘But I cannot.’

‘Why then, did you ask?’

‘Because …’ he stammered. ‘Well, to put it briefly … One of our number failed to ask when he had the chance. He grew tongue-tied or was embarrassed … He didn’t ask and because of that there was great unpleasantness. So now we always ask. Just in case.’

‘Are there sorcerers in this world? You know, people who practise the magical arts. Mages. Knowing Ones.’

‘There’s Merlin. And Morgana. But Morgana is evil.’

‘And Merlin?’

‘Average.’

‘Do you know where to find him?’

‘I’ll say! In Camelot. At the court of King Arthur. I am presently headed there.’

‘Is it far?’

‘From here to Powys, to the River Hafren, then downstream to Glevum, to the Sea of Sabina, and from there to the flatlands of the Summer Land. All in all, some ten days’ ride …’

‘Too far.’

‘One may,’ he stammered, ‘take a short-cut by riding through Cwm Pwcca. But it is an enchanted valley. It is dreadful there. One hears of Y Dynan Bach Têgdwell there, evil little men—’

‘What, do you only carry a sword for decoration?’

‘And what would a sword achieve against witchcraft?’

‘Much, much, don’t worry. I’m a witcher. Ever heard of one? Pshaw, naturally you haven’t. And I’m not afraid of your little men. I have plenty of dwarf friends.’

Of course you do, he thought.

‘Lady of the Lake?’

‘My name’s Ciri. Don’t call me Lady of the Lake. Brings up bad, unpleasant, nasty associations. That’s what they called me in the Land of … What did you call that place?’

‘Faërie. Or, as the druids say: Annwn. And the Saxons say Elfland.’

‘Elfland …’ She wrapped a tartan Pictish rug he had given her around her shoulders. ‘I’ve been there, you know? I entered the Tower of the Swallow and bang! I was among the elves. And that’s exactly what they called me. The Lady of the Lake. I even liked it at the start. It was flattering. Until the moment I understood I was no Lady in that land, in that tower by the lake – but a prisoner.’

‘Was it there,’ he blurted out, ‘that you stained your blouse with blood?’

She was silent for a long while.

‘No,’ she said finally, and her voice, it seemed to him, trembled a little. ‘Not there. You have sharp eyes. Oh well, you can’t flee from the truth, can’t bury your head in the sand … Yes, Galahad. I’ve often become stained lately. With the blood of the foes I’ve killed. And the blood of the friends I tried hard to rescue … And who died in my arms … Why do you stare at me so?’

‘I know not if you be a deity or a mortal … Or one of the goddesses … But if you are a dweller on this earth of ours …’

‘Get to the point, if you would.’

‘I would listen to your story,’ Galahad’s eyes glowed. ‘Would you tell it, O Lady?’

‘It is long.’

‘We have time.’

‘And it doesn’t end so well.’

‘I don’t believe you.’

‘Why?’

‘You were singing when you were bathing in the lake.’

‘You’re observant.’ She turned her head away, pursed her lips and her face suddenly contorted and became ugly. ‘Yes, you’re observant. But very naive.’

‘Tell me your story. Please.’

‘Very well,’ she sighed. ‘Very well, if you wish … I shall.’

She made herself comfortable. As did he. The horses walked by the edge of the forest, nibbling grass and herbs.

‘From the beginning,’ asked Galahad. ‘From the very beginning …’

‘This story,’ she said a moment later, wrapping herself more tightly in the Pictish rug, ‘seems more and more like one without a beginning. Neither am I certain if it has finished yet, either. The past – you have to know – has become awfully tangled up with the future. An elf even told me it’s like that snake that catches its own tail in its teeth. That snake, you ought to know, is called Ouroboros. And the fact it bites its own tail means the circle is closed. The past, present and future lurk in every moment of time. Eternity is hidden in every moment of time. Do you understand?’

‘No.’

‘Never mind.’

Verily do I tell you that whoever believes in dreams is as one trying to catch the wind or seize a shadow. He is deluded by a beguiling picture, a warped looking glass, which lies or utters absurdities in the manner of a woman in labour. Foolish indeed is he who lends credence to dreams and treads the path of delusion.

Nonetheless, whoever disdains and does not believe them at all also acts unwisely. For if dreams had no import whatsoever why, then, would the Gods, in creating us, give us the ability to dream?

The Wisdom of the Prophet Lebioda, 34:1

A light wind ruffled the surface of the lake, which was steaming like a cauldron, and drove ragged wisps of mist over it. Rowlocks creaked and thudded rhythmically, the emerging oar-blades scattering a hail of shining drops.

Condwiramurs put a hand over the side. The boat was moving at such a snail’s pace the water barely foamed or climbed up her hand.

‘Oh, my,’ she said, packing as much sarcasm into her voice as she could. ‘What speed! We’re hurtling over the waves. It’s making my head spin!’

The rower, a short, stocky, compact man, growled back angrily and indistinctly, not even raising his head, which was covered in a grizzly mop of hair as curly as a caracul lamb’s. The novice had put up with quite enough of the growling, hawking and grunting with which the boor had dismissed her questions since she had boarded.

‘Have a care,’ she drawled, struggling to keep calm. ‘You might do yourself a mischief from such hard rowing.’

This time the man raised his face, which was as swarthy and weather-beaten as tanned leather. He grunted, hawked, and pointed his bristly, grey chin at the wooden reel attached to the side of the boat and the line disappearing into the water stretched tight by their movement. Clearly convinced the explanation was exhaustive, he resumed his rowing. With the same rhythm as previously. Oars up. A pause. Blades halfway into the water. A long pause. The pull. An even longer pause.

‘Aha,’ Condwiramurs said nonchalantly, looking heavenwards. ‘I understand. What’s important is the lure being pulled behind the boat, which has to move at the right speed and the right depth. Fishing is important. Everything else is unimportant.’

What she said was so obvious the man didn’t even take the trouble to grunt or wheeze.

‘Who could it bother,’ Condwiramurs continued her monologue, ‘that I’ve been travelling all night? That I’m hungry? That my backside hurts and itches from the hard, wet bench? That I need a pee? No, only trolling for fish matters. Which is pointless in any case. Nothing will take a lure pulled down the middle of the current at a depth of a score of fathoms.’

The man raised his head, looked at her foully and grumbled very – very – grumblingly. Condwiramurs flashed her little teeth, pleased with herself. The boor went on rowing slowly. He was furious.

She lounged back on the stern bench and crossed her legs, letting her dress ride up.

The man grunted, tightened his gnarled hands on the oars, and pretended only to be looking at the fishing line. He had no intention of rowing any faster, naturally. The novice sighed in resignation and turned her attention to the sky.

The rowlocks creaked and the glistening drops fell from the oar blades.

The outline of an island loomed up in the quickly dispersing mist. As did the dark, tapering obelisk of the tower rising above it. The boor, though he was facing forwards and not looking back, knew in some mysterious way that they had almost arrived. Without hurrying, he laid the oars on the gunwales, stood up and began to slowly wind in the line on the reel. Condwiramurs, legs still crossed, whistled, looking up at the sky.

The man finished reeling in the line and examined the lure: a large, brass spoon, armed with a triple hook and a tassel of red wool.

‘Oh my, oh my,’ said Condwiramurs sweetly. ‘Haven’t caught anything? Oh dear, what a pity. I wonder why we’ve had such bad luck? Perhaps the boat was going too fast?’

The man cast her a look which expressed many foul things. He sat down, hawked, spat over the side, grasped the oars in his great knotty hands and bent his back powerfully. The oars splashed, rattled in the rowlocks, and the boat darted across the lake like an arrow, the water foaming with a swoosh against the prow, eddies seething astern. He covered the quarter arrow shot that separated them from the island in less than a grunt, and the boat came up onto the pebbles with such force that Condwiramurs lurched from the bench.

The man grunted, hawked and spat. The novice knew that meant – translated into the speech of civilised people – get out of my boat, you brash witch. She also knew she could forget about being carried ashore. She took off her slippers, lifted her dress provocatively high, and disembarked. She fought back a curse as mussel shells pricked her feet.

‘Thanks,’ she said through clenched teeth, ‘for the ride.’

Neither waiting for the answering grunt nor looking back, she walked barefoot towards the stone steps. All of her discomforts and problems vanished and evaporated without a trace, expunged by her growing excitement. She was there, on the island of Inis Vitre, on Loch Blest. She was in an almost legendary place, where only a select few had ever been.

The morning mist had lifted completely and the red orb of the sun had begun to show more brightly through the dull sky. Squawking gulls circled around the tower’s battlements and swifts flashed by.

At the top of the steps leading from the beach to the terrace, leaning against a statue of a crouching, grinning chimera, was Nimue.

The Lady of the Lake.

She was dainty and short, measuring not much more than five feet. Condwiramurs had heard that when she was young she’d been called ‘Squirt’, and now she knew the nickname had been apt. But she was certain no one had dared call the little sorceress that for at least half a century.

‘I am Condwiramurs Tilly.’ She introduced herself with a bow, a little embarrassed as she was still holding her slippers. ‘I’m glad to be visiting your island, Lady of the Lake.’

‘Nimue,’ the diminutive sorceress corrected her. ‘Nimue, nothing more. We can skip titles and honorifics, Miss Tilly.’

‘In that case I’m Condwiramurs. Condwiramurs, nothing more.’

‘Come with me then, Condwiramurs. We shall talk over breakfast. I imagine you’re hungry.’

‘I don’t deny it.’

There was white curd cheese, chives, eggs, milk and wholemeal bread for breakfast, served by two very young, very quiet serving girls, who smelt of starch. Condwiramurs ate, feeling the gaze of the diminutive sorceress on her.

‘The tower,’ Nimue said slowly, observing her every movement and almost every morsel she raised to her mouth, ‘has six storeys, one of which is below ground. Your room is on the second floor above ground. You’ll find every convenience needed for living. The ground floor, as you see, is the service area. The servants’ quarters are also located here. The subterranean, first and third floors house the laboratory, library and gallery. You may enter and have unfettered access to all the floors I’ve mentioned and the rooms there. You may take advantage of them and of what they contain, when you wish and however you wish.’

‘I understand. Thank you.’

‘The uppermost two storeys contain my private chambers and my private study. Those rooms are absolutely private. In order to avoid misunderstandings: I am extremely sensitive about such things.’

‘I shall respect that.’

Nimue turned her head towards the window, through which the grunting Ferryman could be seen. He had already dealt with Condwiramurs’ luggage, and was now loading rods, reels, landing nets, scoop nets and other fishing tackle into his boat.

‘I’m a little old-fashioned,’ she continued. ‘But I’ve become accustomed to having the exclusive use of certain things. Like a toothbrush, let’s say. My private chambers, library and toilet. And the Fisher King. Do not try, please, to avail yourself of the Fisher King.’

Condwiramurs almost choked on her milk. Nimue’s face didn’t express anything.

‘And if …’ she continued, before the girl had regained her speech, ‘if he tries to avail himself of you, decline him.’

Condwiramurs finally swallowed and nodded quickly, refraining from any comment whatsoever. Though it was on the tip of her tongue to say she didn’t care for anglers, particularly boorish ones. With heads of dishevelled hair as white as curds.

‘Good,’ Nimue drawled. ‘That’s the introductions over and done with. Time to get down to business. Doesn’t it interest you why I chose precisely you from among all the candidates?’

If Condwiramurs pondered the answer at all, it was only so as not to appear too cocksure. She quickly concluded, though, that with Nimue, even the slightest false modesty would offend by its insincerity.

‘I’m the best dream-reader in the academy,’ she replied coolly, matter-of-factly and without boastfulness. ‘And in the third year I was second among the oneiromancers.’

‘I could have taken the number one.’ Nimue was brutal, frank. ‘Incidentally, they suggested that high-flyer somewhat insistently, as it happens, because she was apparently the important daughter of someone important. And where dream-reading and oneiromancy are concerned, you know yourself, my dear Condwiramurs, that it’s a pretty fickle gift. Fiascos can befall even the best dream-reader.’

Condwiramurs kept to herself the riposte that she could count her fiascos on the fingers of one hand. After all, she was talking to a master. Know your limits, my good sir, as one of her professors at the academy, a polymath, used to say.

Nimue praised her silence with a slight nod of her head.

‘I made some enquiries at the academy,’ she said a moment later. ‘Hence, I know that you do not boost your divination with hallucinogens. I’m pleased about that, for I don’t tolerate narcotics.’

‘I divine without any drugs,’ confirmed Condwiramurs with some pride. ‘All I need for oneiroscopy is a hook.’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘You know, a hook,’ the novice coughed, ‘I mean an object in some way connected to what I’m supposed to dream about. Some kind of thing or picture …’

‘A picture?’

‘Uh-huh. I divine pretty well from a picture.’

‘Oh,’ smiled Nimue. ‘Oh, since a painting will help, there won’t be any problem. If you’ve satisfactorily broken your fast, O first dream-reader and second-among-oneiromancers. I ought to explain to you without delay the other reasons why it was you I chose as my assistant.’

Cold emanated from the stone walls, alleviated neither by the heavy tapestries nor the darkened wood panelling. The stone floor chilled her feet through the soles of her slippers.

‘Beyond that door,’ she indicated carelessly, ‘is the laboratory. As has been said before, you may make free use of it. Caution, naturally, is advised. Moderation is particularly recommended during attempts to make brooms carry buckets of water.’

Condwiramurs giggled politely, although the joke was ancient. All the lecturers regaled their charges with jokes referring to the mythical hardships of the mythical sorcerer’s apprentice.

The stairs wound upwards like a sea serpent. And they were precipitous. Before they arrived at their destination Condwiramurs was sweating and panting hard. Nimue showed no signs of effort at all.

‘This way please.’ She opened the oak door. ‘Mind the step.’

Condwiramurs entered and gasped.

The chamber was a picture gallery. The walls were covered from floor to ceiling with paintings. Hanging there were large, old, peeling and cracked oils, miniatures, yellowed prints and engravings, faded watercolours and sepias. There were also vividly coloured gouaches and temperas, clean-of-line aquatints and etchings, lithographs and contrasting mezzotints, drawing the gaze with distinctive dots of black.

Nimue stopped before the picture hanging nearest the door, portraying a group gathered beneath a great tree. She looked at the canvas, then at Condwiramurs, and her mute gaze was unusually eloquent.

‘Dandelion.’ The novice, realising at once what was expected, didn’t make her wait. ‘Singing a ballad beneath the oak Bleobheris.’

Nimue smiled and nodded, and took a step, stopping before the next painting. A wate

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...