- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

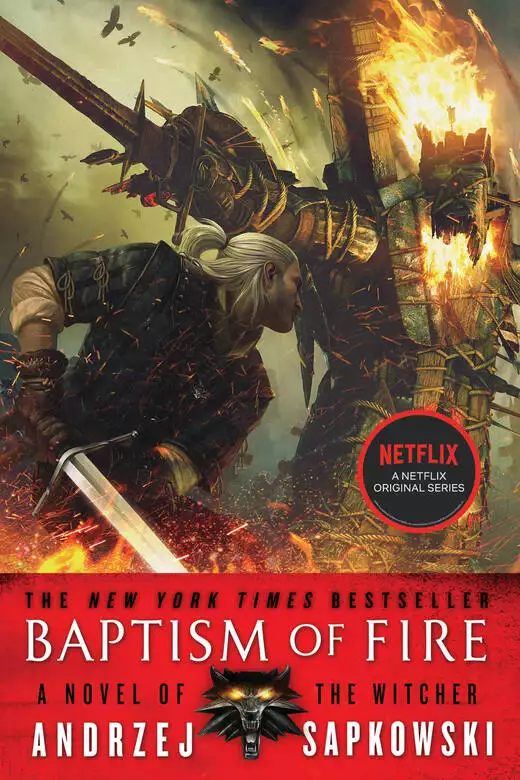

The New York Times bestselling series that inspired the international hit video game: The Witcher

The Wizards Guild has been shattered by a coup and, in the uproar, Geralt was seriously injured. The Witcher is supposed to be a guardian of the innocent, a protector of those in need, a defender against powerful and dangerous monsters that prey on men in dark times.

But now that dark times have fallen upon the world, Geralt is helpless until he has recovered from his injuries.

While war rages across all of the lands, the future of magic is under threat and those sorcerers who survive are determined to protect it. It's an impossible situation in which to find one girl—Ciri, the heiress to the throne of Cintra, has vanished—until a rumor places her in the Niflgaard court, preparing to marry the Emperor.

Injured or not, Geralt has a rescue mission on his hands.

The Witcher returns in this action-packed sequel to The Time of Contempt.

Witcher novels

Blood of Elves

The Time of Contempt

Baptism of Fire

The Tower of Swallows

Lady of the Lake

Witcher collections

The Last Wish

Sword of Destiny

Release date: June 24, 2014

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Baptism of Fire

Andrzej Sapkowski

The slopes of the ravine were overgrown with a dense, tangled mass of brambles and barberry; a perfect place for nesting and feeding. Not surprisingly, it was teeming with birds. Greenfinches trilled loudly, redpolls and whitethroats twittered, and chaffinches gave out ringing ‘vink-vink’s every now and then. The chaffinch’s call signals rain, thought Milva, glancing up at the sky. There were no clouds. But chaffinches always warn of the rain. We could do with a little rain.

Such a spot, opposite the mouth of a ravine, was a good place for a hunter, giving a decent chance of a kill – particularly here in Brokilon Forest, which was abundant with game. The dryads, who controlled extensive tracts of the forest, rarely hunted and humans dared to venture into it even less often. Here, a hunter greedy for meat or pelts became the quarry himself. The Brokilon dryads showed no mercy to intruders. Milva had once discovered that for herself.

No, Brokilon was not short of game. Nonetheless, Milva had been waiting in the undergrowth for more than two hours and nothing had crossed her line of sight. She couldn’t hunt on the move; the drought which had lasted for more than a month had lined the forest floor with dry brush and leaves, which rustled and crackled at every step. In conditions like these, only standing still and unseen would lead to success, and a prize.

An admiral butterfly alighted on the nock of her bow. Milva didn’t shoo it away, but watched it closing and opening its wings. She also looked at her bow, a recent acquisition which she still wasn’t tired of admiring. She was a born archer and loved a good weapon. And she was holding the best of the best.

Milva had owned many bows in her life. She had learned to shoot using ordinary ash and yew bows, but soon gave them up for composite reflex bows, of the type elves and dryads used. Elven bows were shorter, lighter and more manageable and, owing to the laminated composition of wood and animal sinew, much ‘quicker’ than yew bows. An arrow shot with them reached the target much more swiftly and along a flatter arc, which considerably reduced the possibility of its being blown off course. The best examples of such weapons, bent fourfold, bore the elven name of zefhar, since the bow’s shape formed that rune. Milva had used zefhars for several years and couldn’t imagine a bow capable of outclassing them.

But she had finally come across one. It was, of course, at the Seaside Bazaar in Cidaris, which was renowned for its diverse selection of strange and rare goods brought by sailors from the most distant corners of the world; from anywhere a frigate or galleon could reach. Whenever she could, Milva would visit the bazaar and look at the foreign bows. It was there she bought the bow she’d thought would serve her for many years. She had thought the zefhar from Zerrikania, reinforced with polished antelope horn, was perfect. For just a year. Twelve months later, at the same market stall, owned by the same trader, she had found another rare beauty.

The bow came from the Far North. It measured just over five feet, was made of mahogany, had a perfectly balanced riser and flat, laminated limbs, glued together from alternating layers of fine wood, boiled sinew and whalebone. It differed from the other composite bows in its construction and also in its price; which is what had initially caught Milva’s attention. When, however, she picked up the bow and flexed it, she paid the price the trader was asking without hesitation or haggling. Four hundred Novigrad crowns. Naturally, she didn’t have such a titanic sum on her; instead she had given up her Zerrikanian zefhar, a bunch of sable pelts, a small, exquisite elven-made medallion, and a coral cameo pendant on a string of river pearls.

But she didn’t regret it. Not ever. The bow was incredibly light and, quite simply, perfectly accurate. Although it wasn’t long it had an impressive kick to its laminated wood and sinew limbs. Equipped with a silk and hemp bowstring stretched between its precisely curved limbs, it generated fifty-five pounds of force from a twenty-four-inch draw. True enough, there were bows that could generate eighty, but Milva considered that excessive. An arrow shot from her whalebone fifty-fiver covered a distance of two hundred feet in two heartbeats, and at a hundred paces still had enough force to impale a stag, while it would pass right through an unarmoured human. Milva rarely hunted animals larger than red deer or heavily armoured men.

The butterfly flew away. The chaffinches continued to make a racket in the undergrowth. And still nothing crossed her line of sight. Milva leant against the trunk of a pine and began to think back. Simply to kill time.

Her first encounter with the Witcher had taken place in July, two weeks after the events on the Isle of Thanedd and the outbreak of war in Dol Angra. Milva had returned to Brokilon after a fortnight’s absence; she was leading the remains of a Scoia’tael commando defeated in Temeria during an attempt to make their way into war-torn Aedirn. The Squirrels had wanted to join the uprising incited by the elves in Dol Blathanna. They had failed, and would have perished had it not been for Milva. But they’d found her, and refuge in Brokilon.

Immediately on her arrival, she had been informed that Aglaïs needed her urgently in Col Serrai. Milva had been a little taken aback. Aglaïs was the leader of the Brokilon healers, and the deep valley of Col Serrai, with its hot springs and caves, was where healings usually took place.

She responded to the call, convinced it concerned some elf who had been healed and needed her help to re-establish contact with his commando. But when she saw the wounded witcher and learned what it was about, she was absolutely furious. She ran from the cave with her hair streaming behind her and offloaded all her anger on Aglaïs.

‘He saw me! He saw my face! Do you understand what danger that puts me in?’

‘No, no I don’t understand,’ replied the healer coldly. ‘That is Gwynbleidd, the Witcher, a friend of Brokilon. He has been here for a fortnight, since the new moon. And more time will pass before he will be able to get up and walk normally. He craves tidings from the world; news about those close to him. Only you can supply him with that.’

‘Tidings from the world? Have you lost your mind, dryad? Do you know what is happening in the world now, beyond the borders of your tranquil forest? A war is raging in Aedirn! Brugge, Temeria and Redania are reduced to havoc, hell, and much slaughter! Those who instigated the rebellion on Thanedd are being hunted high and low! There are spies and an’givare – informers – everywhere; it’s sometimes sufficient to let slip a single word, make a face at the wrong moment, and you’ll meet the hangman’s red-hot iron in the dungeon! And you want me to creep around spying, asking questions, gathering information? Risking my neck? And for whom? For some half-dead witcher? And who is he to me? My own flesh and blood? You’ve truly taken leave of your senses, Aglaïs.’

‘If you’re going to shout,’ interrupted the dryad calmly, ‘let’s go deeper into the forest. He needs peace and quiet.’

Despite herself, Milva looked over at the cave where she had seen the wounded witcher a moment earlier. A strapping lad, she had thought, thin, yet sinewy… His hair’s white, but his belly’s as flat as a young man’s; hard times have been his companion, not lard and beer…

‘He was on Thanedd,’ she stated; she didn’t ask. ‘He’s a rebel.’

‘I know not,’ said Aglaïs, shrugging. ‘He’s wounded. He needs help. I’m not interested in the rest.’

Milva was annoyed. The healer was known for her taciturnity. But Milva had already heard excited accounts from dryads in the eastern marches of Brokilon; she already knew the details of the events that had occurred a fortnight earlier. About the chestnut-haired sorceress who had appeared in Brokilon in a burst of magic; about the cripple with a broken arm and leg she had been dragging with her. A cripple who had turned out to be the Witcher, known to the dryads as Gwynbleidd: the White Wolf.

At first, according to the dryads, no one had known what steps to take. The mutilated witcher screamed and fainted by turns, Aglaïs had applied makeshift dressings, the sorceress cursed and wept. Milva did not believe that at all: who has ever seen a sorceress weep? And later the order came from Duén Canell, from the silver-eyed Eithné, the Lady of Brokilon. Send the sorceress away, said the ruler of the Forest of the Dryads. And tend to the Witcher.

And so they did. Milva had seen as much. He was lying in a cave, in a hollow full of water from the magical Brokilon springs. His limbs, which had been held in place using splints and put in traction, were swathed in a thick layer of the healing climbing plant – conynhaela – and turfs of knitbone. His hair was as white as milk. Unusually, he was conscious: anyone being treated with conynhaela normally lay lifeless and raving as the magic spoke through them…

‘Well?’ the healer’s emotionless voice tore her from her reverie. ‘What is it going to be? What am I to tell him?’

‘To go to hell,’ snapped Milva, lifting her belt, from which hung a heavy purse and a hunting knife. ‘And you can go to hell, too, Aglaïs.’

‘As you wish. I shall not compel you.’

‘You are right. You will not.’

She went into the forest, among the sparse pines, and didn’t look back. She was angry.

Milva knew about the events which had taken place during the first July new moon on the Isle of Thanedd; the Scoia’tael talked about it endlessly. There had been a rebellion during the Mages’ Conclave on the island. Blood had been spilt and heads had rolled. And, as if on a signal, the armies of Nilfgaard had attacked Aedirn and Lyria and the war had begun. And in Temeria, Redania and Kaedwen it was all blamed on the Squirrels. For one thing, because a commando of Scoia’tael had supposedly come to the aid of the rebellious mages on Thanedd. For another, because an elf or possibly half-elf had supposedly stabbed and killed Vizimir, King of Redania. So the furious humans had gone after the Squirrels with a vengeance. The fighting was raging everywhere and elven blood was flowing in rivers…

Ha, thought Milva, perhaps what the priests are saying is true after all and the end of the world and the day of judgement are close at hand? The world is in flames, humans are preying not only on elves but on other humans too. Brothers are raising knives against brothers… And the Witcher is meddling in politics… and joining the rebellion. The Witcher, who is meant to roam the world and kill monsters eager to harm humans! No witcher, for as long as anyone can remember, has ever allowed himself to be drawn into politics or war. Why, there’s even the tale about a foolish king who carried water in a sieve, took a hare as a messenger, and appointed a witcher as a palatine. And yet here we have the Witcher, carved up in a rebellion against the kings and forced to escape punishment in Brokilon. Perhaps it truly is the end of the world!

‘Greetings, Maria.’

She started. The short dryad leaning against a pine had eyes and hair the colour of silver. The setting sun gave her head a halo against the background of the motley wall of trees. Milva dropped to one knee and bowed low.

‘My greetings to you, Lady Eithné.’

The ruler of Brokilon stuck a small, crescent-shaped, golden knife into a bast girdle.

‘Arise,’ she said. ‘Let us take a walk. I wish to talk with you.’

They walked for a long time through the shadowy forest; the delicate, silver-haired dryad and the tall, flaxen-haired girl. Neither of them broke the silence for some time.

‘It is long since you were at Duén Canell, Maria.’

‘There was no time, Lady Eithné. It is a long road to Duén Canell from the River Ribbon, and I… But of course you know.’

‘That I do. Are you weary?’

‘The elves need my help. I’m helping them on your orders, after all.’

‘At my request.’

‘Indeed. At your request.’

‘And I have one more.’

‘As I thought. The Witcher?’

‘Help him.’

Milva stopped and turned back, breaking an overhanging twig of honeysuckle with a sharp movement, turning it over in her fingers before flinging it to the ground.

‘For half a year,’ she said softly, looking into the dryad’s silvery eyes, ‘I have risked my life guiding elves from their decimated commandos to Brokilon… When they are rested and their wounds healed, I lead them out again… Is that so little? Haven’t I done enough? Every new moon, I set out on the trail in the dark of the night. I’ve begun to fear the sun as much as a bat or an owl does…’

‘No one knows the forest trails better than you.’

‘I will not learn anything in the greenwood. I hear that the Witcher wants me to gather news, by moving among humans. He’s a rebel, the ears of the an’givare prick up at the sound of his name. I must be careful not to show myself in the cities. And what if someone recognises me? The memories still endure, the blood is not yet dry… for there was a lot of blood, Lady Eithné.’

‘A great deal.’ The silver eyes of the old dryad were alien, cold; inscrutable. ‘A great deal, indeed.’

‘Were they to recognise me, they would impale me.’

‘You are prudent. You are cautious and vigilant.’

‘In order to gather the tidings the Witcher requests, it is necessary to shed vigilance. It is necessary to ask. And now it is dangerous to demonstrate curiosity. Were they to capture me—’

‘You have contacts.’

‘They would torture me. Until I died. Or grind me down in Drakenborg—’

‘But you are indebted to me.’

Milva turned her head away and bit her lip.

‘It’s true, I am,’ she said bitterly. ‘I have not forgotten.’

She narrowed her eyes, her face suddenly contorted, and she clenched her teeth tightly. The memory shone faintly beneath her eyelids; the ghastly moonlight of that night. The pain in her ankle suddenly returned, held tight by the leather snare, and the pain in her joints, after they had been cruelly wrenched. She heard again the soughing of leaves as the tree shot suddenly upright… Her screaming, moaning; the desperate, frantic, horrified struggle and the invasive sense of fear which flowed over her when she realised she couldn’t free herself… The cry and fear, the creak of the rope, the rippling shadows; the swinging, unnatural, upturned earth, upturned sky, trees with upturned tops, pain, blood pounding in her temples…

And at dawn the dryads, all around her, in a ring… The distant silvery laughter… A puppet on a string! Swing, swing, marionette, little head hanging down… And her own, unnatural, wheezing cry. And then darkness.

‘Indeed, I have a debt,’ she said through clenched teeth. ‘Indeed, for I was a hanged man cut from the noose. As long as I live, I see, I shall never pay off that debt.’

‘Everyone has some kind of debt,’ replied Eithné. ‘Such is life, Maria Barring. Debts and liabilities, obligations, gratitude, payments… Doing something for someone. Or perhaps for ourselves? For in fact we are always paying ourselves back and not someone else. Each time we are indebted we pay off the debt to ourselves. In each of us lies a creditor and a debtor at once and the art is for the reckoning to tally inside us. We enter the world as a minute part of the life we are given, and from then on we are ever paying off debts. To ourselves. For ourselves. In order for the final reckoning to tally.’

‘Is this human dear to you, Lady Eithné? That… that witcher?’

‘He is. Although he knows not of it. Return to Col Serrai, Maria Barring. Go to him. And do what he asks of you.’

In the valley, the brushwood crunched and a twig snapped. A magpie gave a noisy, angry ‘chacker-chacker’, and some chaffinches took flight, flashing their white wing bars and tail feathers. Milva held her breath. At last.

Chacker-chacker, called the magpie. Chacker-chacker-chacker. Another twig cracked.

Milva adjusted the worn, polished leather guard on her left forearm, and placed her hand through the loop attached to her gear. She took an arrow from the flat quiver on her thigh. Out of habit, she checked the arrowhead and the fletchings. She bought shafts at the market – choosing on average one out of every dozen offered to her – but she always fletched them herself. Most ready-made arrows in circulation had too-short fletchings arranged straight along the shaft, while Milva only used spirally fletched arrows, with the fletchings never shorter than five inches.

She nocked the arrow and stared at the mouth of the ravine, at a green spot of barberry among the trees, heavy with bunches of red berries.

The chaffinches had not flown far and began their trilling again. Come on, little one, thought Milva, raising the bow and drawing the bowstring. Come on. I’m ready.

But the roe deer headed along the ravine, towards the marsh and springs which fed the small streams flowing into the Ribbon. A young buck came out of the ravine. A fine specimen, weighing in – she estimated – at almost four stone. He lifted his head, pricked up his ears, and then turned back towards the bushes, nibbling leaves.

With his back toward her, he was an easy victim. Had it not been for a tree trunk obscuring part of the target, Milva would have fired without a second thought. Even if she were to hit him in the belly, the arrow would penetrate and pierce the heart, liver or lungs. Were she to hit him in the haunch, she would destroy an artery, and the animal would be sure to fall in a short time. She waited, without releasing the bowstring.

The buck raised his head again, stepped out from behind the trunk and abruptly turned round a little. Milva, holding the bow at full draw, cursed under her breath. A shot face-on was uncertain; instead of hitting the lung, the arrowhead might enter the stomach. She waited, holding her breath, aware of the salty taste of the bowstring against the corner of her mouth. That was one of the most important, quite invaluable, advantages of her bow; were she to use a heavier or inferior weapon, she would never be able to hold it fully drawn for so long without tiring or losing precision with the shot.

Fortunately, the buck lowered his head, nibbled on some grass protruding from the moss and turned to stand sideways. Milva exhaled calmly, took aim at his chest and gently released her fingers from the bowstring.

She didn’t hear the expected crunch of ribs being broken by the arrow, however. For the buck leapt upwards, kicked and fled, accompanied by the crackling of dry branches and the rustle of leaves being shoved aside.

Milva stood motionless for several heartbeats, petrified like a marble statue of a forest goddess. Only when all the noises had subsided did she lift her hand from her cheek and lower the bow. Having made a mental note of the route the animal had taken as it fled, she sat down calmly, resting her back against a tree trunk. She was an experienced hunter, she had poached in the lord’s forests from a child. She had brought down her first roe deer at the age of eleven, and her first fourteen-point buck on the day of her fourteenth birthday – an exceptionally favourable augury. And experience had taught that one should never rush after a shot animal. If she had aimed well, the buck would fall no further than two hundred paces from the mouth of the ravine. Should she have been off target – a possibility she actually didn’t contemplate – hurrying might only make things worse. A badly injured animal, which wasn’t agitated, would slow to a walk after its initial panicked flight. A frightened animal being pursued would race away at breakneck speed and would only slow down once it was over the hills and far away.

So she had at least half an hour. She plucked a blade of grass, stuck it between her teeth and drifted off in thought once again. The memories came back.

When she returned to Brokilon twelve days later, the Witcher was already up and about. He was limping somewhat and slightly dragging one hip, but he was walking. Milva was not surprised – she knew of the miraculous healing properties of the forest water and the herb conynhaela. She also knew Aglaïs’s abilities and on several occasions had witnessed the astonishingly quick return to health of wounded dryads. And the rumours about the exceptional resistance and endurance of witchers were also clearly no mere myths either.

She did not go to Col Serrai immediately on her arrival, although the dryads hinted that Gwynbleidd had been impatiently awaiting her return. She delayed intentionally, still unhappy with her mission and wanting to make her feelings clear. She escorted the Squirrels back to their camp. She gave a lengthy account of the incidents on the road and warned the dryads about the plans to seal the border on the Ribbon by humans. Only when she was rebuked for the third time did Milva bathe, change and go to the Witcher.

He was waiting for her at the edge of a glade by some cedars. He was walking up and down, squatting from time to time and then straightening up with a spring. Aglaïs had clearly ordered him to exercise.

‘What news?’ he asked immediately after greeting her. The coldness in his voice didn’t deceive her.

‘The war seems to be coming to an end,’ she answered, shrugging. ‘Nilfgaard, they say, has crushed Lyria and Aedirn. Verden has surrendered and the King of Temeria has struck a deal with the Nilfgaardian emperor. The elves in the Valley of Flowers have established their own kingdom but the Scoia’tael from Temeria and Redania have not joined them. They are still fighting…’

‘That isn’t what I meant.’

‘No?’ she said, feigning surprise. ‘Oh, I see. Well, I stopped in Dorian, as you asked, though it meant going considerably out of my way. And the highways are so dangerous now…’

She broke off, stretching. This time he didn’t hurry her.

‘Was Codringher,’ she finally asked, ‘whom you asked me to visit, a close friend of yours?’

The Witcher’s face did not twitch, but Milva knew he understood at once.

‘No. He wasn’t.’

‘That’s good,’ she continued easily. ‘Because he’s no longer with us. He went up in flames along with his chambers; probably only the chimney and half of the façade survived. The whole of Dorian is abuzz with rumours. Some say Codringher was dabbling in black magic and concocting poisons; that he had a pact with the devil, so the devil’s fire consumed him. Others say he’d stuck his nose and his fingers into a crack he shouldn’t have, as was his custom. And it wasn’t to somebody’s liking, so they bumped him off and set everything alight, to cover their tracks. What do you think?’

She didn’t receive a reply, or detect any emotion on his ashen face. So she continued, in the same venomous, arrogant tone of voice.

‘It’s interesting that the fire and Codringher’s death occurred during the first July new moon, exactly when the unrest on the Isle of Thanedd was taking place. As if someone had guessed that Codringher knew something about the disturbances and would be asked for details. As if someone wanted to stop his trap up good and proper in advance, strike him dumb. What do you say to that? Ah, I see you won’t say anything. You’re keeping quiet, so I’ll tell you this: your activities are dangerous, and so is your spying and questioning. Perhaps someone will want to shut other traps and ears than Codringher’s. That’s what I think.’

‘Forgive me,’ he said a moment later. ‘You’re right. I put you at risk. It was too dangerous a task for a—’

‘For a woman, you mean?’ she said, jerking her head back, flicking her still wet hair from her shoulder with a sudden movement. ‘Is that what you were going to say? Are you playing the gentleman all of a sudden? I may have to squat to piss, but my coat is lined with wolf skin, not coney fur! Don’t call me a coward, because you don’t know me!’

‘I do,’ he said in a calm, quiet voice, not reacting to her anger or raised voice. ‘You are Milva. You lead Squirrels to safety in Brokilon, avoiding capture. Your courage is known to me. But I recklessly and selfishly put you at risk—’

‘You’re a fool!’ she interrupted sharply. ‘Worry about yourself, not about me. Worry about that young girl!’

She smiled disdainfully. Because this time his face did change. She fell silent deliberately, waiting for further questions.

‘What do you know?’ he finally asked. ‘And from whom?’

‘You had your Codringher,’ she snorted, lifting her head proudly. ‘And I have my own contacts. The kind with sharp eyes and ears.’

‘Tell me, Milva. Please.’

‘After the fighting on Thanedd,’ she began, after waiting a moment, ‘unrest erupted everywhere. The hunt for traitors began, particularly for any sorcerers who supported Nilfgaard and for the other turncoats. Some were captured, others vanished without trace. You don’t need much nous to guess where they fled to and under whose wings they’re hiding. But it wasn’t just sorcerers and traitors who were hunted. A Squirrel commando led by the famous Faoiltiarna also helped the mutinous sorcerers in the rebellion on Thanedd. So now he’s wanted. An order has been issued that every elf captured should be tortured and interrogated about Faoiltiarna’s commando.’

‘Who’s Faoiltiarna?’

‘An elf, one of the Scoia’tael. Few have got under the humans’ skin the way he has. There’s a hefty bounty on his head. But they’re seeking another too. A Nilfgaardian knight who was on Thanedd. And also for a…’

‘Go on.’

‘The an’givare are asking about a witcher who goes by the name of Geralt of Rivia. And about a girl named Cirilla. Those two are to be captured alive. It was ordered on pain of death: if either of you is caught, not a hair on your heads is to be harmed, not a button may be torn from her dress. Oh! You must be dear to their hearts for them to care so much about your health…’

She broke off, seeing the expression on his face, from which his unnatural composure had abruptly disappeared. She realised that however hard she tried, she was unable to make him afraid. At least not for his own skin. She unexpectedly felt ashamed.

‘Well, that pursuit of theirs is futile,’ she said gently, with just a faintly mocking smile on her lips. ‘You are safe in Brokilon. And they won’t catch the girl alive either. When they searched through the rubble on Thanedd, all the debris from that magical tower which collapsed—Hey, what’s wrong with you?’

The Witcher staggered, leant against a cedar, and sat down heavily near the trunk. Milva leapt back, horrified by the pallor which his already whitened face had suddenly taken on.

‘Aglaïs! Sirssa! Fauve! Come quickly! Damn, I think he’s about to keel over! Hey, you!’

‘Don’t call them… There’s nothing wrong with me. Speak. I want to know…’

Milva suddenly understood.

‘They found nothing in the debris!’ she cried, feeling herself go pale too. ‘Nothing! Although they examined every stone and cast spells, they didn’t find…’

She wiped the sweat from her forehead and held back with a gesture the dryads running towards them. She seized the Witcher by his shoulders and leant over him so that her long hair tumbled over his pale face.

‘You misunderstood me,’ she said quickly, incoherently; it was difficult to find the right words among the mass which were trying to tumble out. ‘I only meant—You understood me wrongly. Because I… How was I to know she is so… No… I didn’t mean to. I only wanted to say that the girl… That they won’t find her, because she disappeared without a trace, like those mages. Forgive me.’

He didn’t answer. He looked away. Milva bit her lip and clenched her fists.

‘I’m leaving Brokilon again in three days,’ she said gently after a long, very long, silence. ‘The moon must wane a little and the nights become a little darker. I shall return within ten days, perhaps sooner. Shortly after Lammas, in the first days of August. Worry not. I shall move earth and water, but I shall find out everything. If anyone knows anything about that maiden, you’ll know it too.’

‘Thank you, Milva.’

‘I’ll see you in ten days… Gwynbleidd.’

‘Call me Geralt,’ he said, holding out a hand. She took it without a second thought. And squeezed it very hard.

‘And I’m Maria Barring.’

A nod of the head and the flicker of a smile thanked her for her sincerity. She knew he appreciated it.

‘Be careful, please. When you ask questions, be careful who you ask.’

‘Don’t worry about me.’

‘Your informers… Do you trust them?’

‘I don’t trust anyone.’

‘The Witcher is in Brokilon. Among the dryads.’

‘As I thought,’ Dijkstra said, folding his arms on his chest. ‘But I’m glad it’s been confirmed.’

He remained silent for a moment. Lennep licked his lips. And waited.

‘I’m glad it’s been confirmed,’ repeated the head of the secret service of the Kingdom of Redania, pensively, as though he were talking to himself. ‘It’s always better to be certain. If only Yennefer were with him… There isn’t a witch with him, is there, Lennep?’

‘I beg your pardon?’ the spy started. ‘No, Your Lordship. There isn’t. What

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...