- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

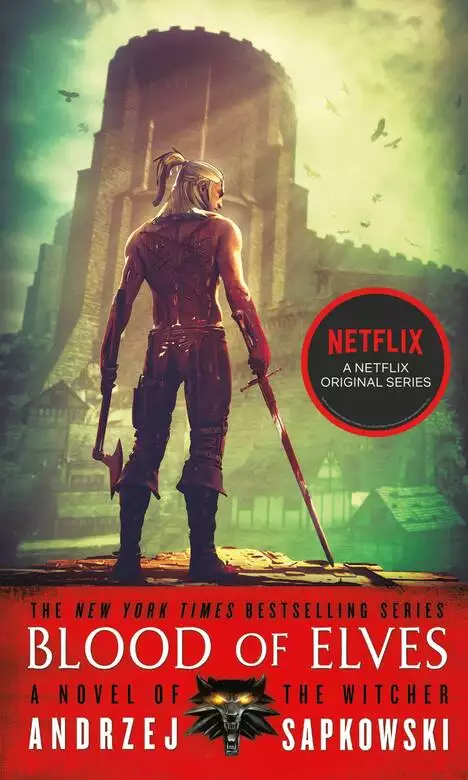

The New York Times bestselling series that inspired the international hit video game: The Witcher.

For over a century, humans, dwarves, gnomes, and elves have lived together in relative peace. But times have changed, the uneasy peace is over, and now the races are fighting once again. The only good elf, it seems, is a dead elf.

Geralt of Rivia, the cunning assassin known as The Witcher, has been waiting for the birth of a prophesied child. This child has the power to change the world—for good, or for evil.

As the threat of war hangs over the land and the child is hunted for her extraordinary powers, it will become Geralt's responsibility to protect them all—and the Witcher never accepts defeat.

Blood of Elves is the first full-length Witcher novel, and the perfect follow up if you've read The Last Wish collection.

Witcher novels

Blood of Elves

The Time of Contempt

Baptism of Fire

The Tower of Swallows

Lady of the Lake

Witcher collections

The Last Wish

Sword of Destiny

Release date: May 1, 2009

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 416

Reader says this book is...: entertaining story (1) epic storytelling (1) great world-building (1) terrific writing (1)

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Blood of Elves

Andrzej Sapkowski

BLOOD OF ELVES

look out for

THE TOWER OF FOOLS

Book One of the Hussite Trilogy

by

Andrzej Sapkowski

Andrzej Sapkowski, winner of the World Fantasy Award for Lifetime Achievement, created an international phenomenon with his New York Times bestselling Witcher series. Now he introduces readers to a new hero: Reynevan, a young magician and healer journeying across a war-torn land.

When a thoughtless indiscretion finds Reinmar of Bielawa caught in the crosshairs of a powerful noble family, he is forced to flee his home.

But once he passes beyond the city walls, he finds that there are dangers ahead as well as behind. Pursued by dark forces both human and mystic, Reynevan finds himself in the Narrenturm, the Tower of Fools, a medieval asylum for the mad—or for those who dare to think differently and challenge the prevailing order.

Gloria Patri, et Filio et Spiritui sancto.

Sicut erat in principio, et nunc, et semper

et in saecula saeculorum, Amen.

Alleluia!

As the monks concluded the Gloria, Reynevan, kissing the back of Adèle of Stercza’s neck, placed his hand beneath her orchard of pomegranates, engrossed, mad, like a young hart skipping upon the mountains to his beloved…

A mailed fist struck the door, which thudded open with such force that the lock was torn off the frame and shot through the window like a meteor. Adèle screamed shrilly as the Stercza brothers burst into the chamber.

Reynevan tumbled out of bed, positioning it between himself and the intruders, grabbed his clothes and began to hurriedly put them on. He largely succeeded, but only because the brothers Stercza had directed their frontal attack at their sister-in-law.

“You vile harlot!” bellowed Morold of Stercza, dragging a naked Adèle from the bedclothes.

“Wanton whore!” chimed in Wittich, his older brother, while Wolfher—next oldest after Adèle’s husband Gelfrad—did not even open his mouth, for pale fury had deprived him of speech. He struck Adèle hard in the face. The Burgundian screamed. Wolfher struck her again, this time backhanded.

“Don’t you dare hit her, Stercza!” yelled Reynevan, but his voice broke and trembled with fear and a paralysing feeling of impotence, caused by his trousers being round his knees. “Don’t you dare!”

His cry achieved its effect, although not the way he had intended. Wolfher and Wittich, momentarily forgetting their adulterous sister-in-law, pounced on Reynevan, raining down a hail of punches and kicks on the boy. He cowered under the blows, but rather than defend or protect himself, he stubbornly pulled on his trousers as though they were some kind of magical armour. Out of the corner of one eye, he saw Wittich drawing a knife. Adèle screamed.

“Don’t,” Wolfher snapped at his brother. “Not here!”

Reynevan managed to get onto his knees. Wittich, face white with fury, jumped at him and punched him, throwing him to the floor again. Adèle let out a piercing scream, which broke off as Morold struck her in the face and pulled her hair.

“Don’t you dare…” Reynevan groaned “… hit her, you scoundrels!”

“Bastard!” yelled Wittich. “Just you wait!”

Wittich leaped forward, punched and kicked once and twice. Wolfher stopped him at the third.

“Not here,” Wolfher repeated calmly, but it was a baleful calm. “Into the courtyard with him. We’ll take him to Bierutów. That slut, too.”

“I’m innocent!” wailed Adèle of Stercza. “He bewitched me! Enchanted me! He’s a sorcerer! Sorcier! Diab—”

Morold silenced her with another punch. “Hold your tongue, trollop,” he growled. “You’ll get the chance to scream. Just wait awhile.”

“Don’t you dare hit her!” yelled Reynevan.

“We’ll give you a chance to scream, too, little rooster,” Wolfher added, still menacingly calm. “Come on, out with him.”

The Stercza brothers threw Reynevan down the garret’s steep stairs and the boy tumbled onto the landing, splintering part of the wooden balustrade. Before he could get up, they seized him again and threw him out into the courtyard, onto sand strewn with steaming piles of horse shit.

“Well, well, well,” said Nicolaus of Stercza, the youngest of the brothers, barely a stripling, who was holding the horses. “Look who’s stopped by. Could it be Reinmar of Bielawa?”

“The scholarly braggart Bielawa,” snorted Jentsch of Knobelsdorf, known as Eagle Owl, a comrade and relative of the Sterczas. “The arrogant know-all Bielawa!”

“Shitty poet,” added Dieter Haxt, another friend of the family. “Bloody Abélard!”

“And to prove to him we’re well read, too,” said Wolfher as he descended the stairs, “we’ll do to him what they did to Abélard when he was caught with Héloïse. Well, Bielawa? How do you fancy being a capon?”

“Go fuck yourself, Stercza.”

“What? What?” Although it seemed impossible, Wolfher Stercza had turned even paler. “The rooster still has the audacity to open his beak? To crow? The bullwhip, Jentsch!”

“Don’t you dare beat him!” Adèle called impotently as she was led down the stairs, now clothed, albeit incompletely. “Don’t you dare! Or I’ll tell everyone what you are like! That you courted me yourself, pawed me and tried to debauch me behind your brother’s back! That you swore vengeance on me if I spurned you! Which is why you are so… so…”

She couldn’t find the German word and the entire tirade fell apart. Wolfher just laughed.

“Verily!” he mocked. “People will listen to the Frenchwoman, the lewd strumpet. The bullwhip, Eagle Owl!”

The courtyard was suddenly awash with black Augustinian habits.

“What is happening here?” shouted the venerable Prior Erasmus Steinkeller, a bony and sallow old man. “Christians, what are you doing?”

“Begone!” bellowed Wolfher, cracking the bullwhip. “Begone, shaven-heads, hurry off to your prayer books! Don’t interfere in knightly affairs, or woe betide you, blackbacks!”

“Good Lord.” The prior put his liver-spotted hands together. “Forgive them, for they know not what they do. In nomine Patris, et Filii—”

“Morold, Wittich!” roared Wolfher. “Bring the harlot here! Jentsch, Dieter, bind her paramour!”

“Or perhaps,” snarled Stefan Rotkirch, another friend of the family who had been silent until then, “we’ll drag him behind a horse a little?”

“We could. But first, we’ll give him a flogging!”

Wolfher aimed a blow with the horsewhip at the still-prone Reynevan but did not connect, as his wrist was seized by Brother Innocent, nicknamed “Brother Insolent” by his fellow friars, whose impressive height and build were apparent despite his humble monkish stoop. His vicelike grip held Wolfher’s arm motionless.

Stercza swore coarsely, jerked himself away and gave the monk a hard shove. But he might as well have shoved the tower in Oleśnica Castle for all the effect it had. Brother Innocent didn’t budge an inch. He shoved Wolfher back, propelling him halfway across the courtyard and dumping him in a pile of muck.

For a moment, there was silence. And then they all rushed the huge monk. Eagle Owl, the first to attack, was punched in the teeth and tumbled across the sand. Morold of Stercza took a thump to the ear and staggered off to one side, staring vacantly. The others swarmed over the Augustinian like ants, raining blows on the monk’s huge form. Brother Insolent retaliated just as savagely and in a distinctly unchristian way, quite at odds with Saint Augustine’s rule of humility.

The sight enraged the old prior. He flushed like a beetroot, roared like a lion and rushed into the fray, striking left and right with heavy blows of his rosewood crucifix.

“Pax!” he bellowed as he struck. “Pax! Vobiscum! Love thy neighbour! Proximum tuum! Sicut te ipsum! Whoresons!”

Dieter Haxt punched him hard. The old man was flung over backwards and his sandals flew up, describing pretty trajectories in the air. The Augustinians cried out and several of them charged into battle, unable to restrain themselves. The courtyard was seething in earnest.

Wolfher of Stercza, who had been shoved out of the confusion, drew a short sword and brandished it—bloodshed looked inevitable. But Reynevan, who had finally managed to stand up, whacked him in the back of the head with the handle of the bullwhip he had picked up. Stercza held his head and turned around, only for Reynevan to lash him across the face. As Wolfher fell to the ground, Reynevan rushed towards the horses.

“Adèle! Here! To me!”

Adèle didn’t even budge, and the indifference painted on her face was alarming. Reynevan leaped into the saddle. The horse neighed and fidgeted.

“Adèèèèèèle!”

Morold, Wittich, Haxt and Eagle Owl were now running towards him. Reynevan reined the horse around, whistled piercingly and spurred it hard, making for the gate.

“After him!” yelled Wolfher. “To your horses and get after him!”

Reynevan’s first thought was to head towards Saint Mary’s Gate and out of the town into the woods, but the stretch of Cattle Street leading to the gate was totally crammed with wagons. Furthermore, the horse, urged on and frightened by the cries of an unfamiliar rider, was showing great individual initiative, so before he knew it, Reynevan was hurtling along at a gallop towards the town square, splashing mud and scattering passers-by. He didn’t have to look back to know the others were hot on his heels given the thudding of hooves, the neighing of horses, the angry roaring of the Sterczas and the furious yelling of people being jostled.

He jabbed the horse to a full gallop with his heels, hitting and knocking over a baker carrying a basket. A shower of loaves and pastries flew into the mud, soon to be trodden beneath the hooves of the Sterczas’ horses. Reynevan didn’t even look back, more concerned with what was ahead of him than behind. A cart piled high with faggots of brushwood loomed up before his eyes. The cart was blocking almost the entire street, the rest of which was occupied by a group of half-clothed urchins, kneeling down and busily digging something extremely engrossing out of the muck.

“We have you, Bielawa!” thundered Wolfher from behind, also seeing the obstruction.

Reynevan’s horse was racing so swiftly there was no chance of stopping it. He pressed himself against its mane and closed his eyes. As a result, he didn’t see the half-naked children scatter with the speed and grace of rats. He didn’t look back, so nor did he see a peasant in a sheepskin jerkin turn around, somewhat stupefied, as he hauled a cart into the road. Nor did he see the Sterczas riding broadside into the cart. Nor Jentsch of Knobelsdorf soaring from the saddle and sweeping half of the faggots from the cart with his body.

Reynevan galloped down Saint John’s Street, between the town hall and the burgermeister’s house, hurtling at full speed into Oleśnica’s huge and crowded town square. Pandemonium erupted. Aiming for the southern frontage and the squat, square tower of the Oława Gate visible above it, Reynevan galloped through the crowds, leaving havoc behind him. Townsfolk yelled and pigs squealed, as overturned stalls and benches showered a hail of household goods and foodstuffs of every kind in all directions. Clouds of feathers flew everywhere as the Sterczas—hot on Reynevan’s heels—added to the destruction.

Reynevan’s horse, frightened by a goose flying past its nose, recoiled and hurtled into a fish stall, shattering crates and bursting open barrels. The enraged fishmonger made a great swipe with a keep net, missing Reynevan but striking the horse’s rump. The horse whinnied and slewed sideways, upending a stall selling thread and ribbons, and only a miracle prevented Reynevan from falling. Out of the corner of one eye, he saw the stallholder running after him brandishing a huge cleaver (serving God only knew what purpose in the haberdashery trade). Spitting out some goose feathers stuck to his lips, he brought the horse under control and galloped through the shambles, knowing that the Oława Gate was very close.

“I’ll tear your balls off, Bielawa!” Wolfher of Stercza roared from behind. “I’ll tear them off and stuff them down your throat!”

“Kiss my arse!”

Only four men were chasing him now—Rotkirch had been pulled from his horse and was being roughed up by some infuriated market traders.

Reynevan darted like an arrow down an avenue of animal carcasses suspended by their legs. Most of the butchers leaped back in alarm, but one carrying a large haunch of beef on one shoulder tumbled under the hooves of Wittich’s horse, which took fright, reared up and was ploughed into by Wolfher’s horse. Wittich flew from the saddle straight onto the meat stall, nose-first into livers, lights and kidneys, and was then landed on by Wolfher. His foot was caught in the stirrup and before he could free himself, he had destroyed a large number of stalls and covered himself in mud and blood.

At the last moment, Reynevan quickly lowered his head over the horse’s neck to duck under a wooden sign with a piglet’s head painted on it. Dieter Haxt, who was bearing down on him, wasn’t quick enough and the cheerfully grinning piglet slammed into his forehead. Dieter flew from the saddle and crashed into a pile of refuse, frightening some cats. Reynevan turned around. Now only Nicolaus of Stercza was keeping up with him.

Reynevan shot out of the chaos at a full gallop and into a small square where some tanners were working. As a frame hung with wet hides loomed up before him, he urged his horse to jump. It did. And Reynevan didn’t fall off. Another miracle.

Nicolaus wasn’t as lucky. His horse skidded to a halt in front of the frame and collided with it, slipping on the mud and scraps of meat and fat. The youngest Stercza shot over his horse’s head, with very unfortunate results. He flew belly-first right onto a scythe used for scraping leather which the tanners had left propped up against the frame.

At first, Nicolaus had no idea what had happened. He got up from the ground, caught hold of his horse, and only when it snorted and stepped back did his knees sag and buckle beneath him. Still not really knowing what was happening, the youngest Stercza slid across the mud after the panicked horse, which was still moving back and snorting. Finally, as he released the reins and tried to get to his feet again, he realised something was wrong and looked down at his midriff.

And screamed.

He dropped to his knees in the middle of a rapidly spreading pool of blood.

Dieter Haxt rode up, reined in his horse and dismounted. A moment later, Wolfher and Wittich followed suit.

Nicolaus sat down heavily. Looked at his belly again. Screamed and then burst into tears. His eyes began to glaze over as the blood gushing from him mingled with the blood of the oxen and hogs butchered that morning.

“Nicolaaaaus!” yelled Wolfher.

Nicolaus of Stercza coughed and choked. And died.

“You are dead, Reinmar of Bielawa!” Wolfher of Stercza, pale with fury, bellowed towards the gate. “I’ll catch you, kill you, destroy you. Exterminate you and your entire viperous family. Your entire viperous family, do you hear?”

Reynevan didn’t. Amid the thud of horseshoes on the bridge planks, he was leaving Oleśnica and dashing south, straight for the Wrocław highway.

The town was in flames.

The narrow streets leading to the moat and the first terrace belched smoke and embers, flames devouring the densely clustered thatched houses and licking at the castle walls. From the west, from the harbour gate, the screams and clamour of vicious battle and the dull blows of a battering ram smashing against the walls grew ever louder.

Their attackers had surrounded them unexpectedly, shattering the barricades which had been held by no more than a few soldiers, a handful of townsmen carrying halberds and some crossbowmen from the guild. Their horses, decked out in flowing black caparisons, flew over the barricades like spectres, their riders’ bright, glistening blades sowing death amongst the fleeing defenders.

Ciri felt the knight who carried her before him on his saddle abruptly spur his horse. She heard his cry. “Hold on,” he shouted. “Hold on!”

Other knights wearing the colours of Cintra overtook them, sparring, even in full flight, with the Nilfgaardians. Ciri caught a glimpse of the skirmish from the corner of her eye—the crazed swirl of blue-gold and black cloaks amidst the clash of steel, the clatter of blades against shields, the neighing of horses—

Shouts. No, not shouts. Screams.

“Hold on!”

Fear. With every jolt, every jerk, every leap of the horse pain shot through her hands as she clutched at the reins. Her legs contracted painfully, unable to find support, her eyes watered from the smoke. The arm around her suffocated her, choking her, the force compressing her ribs. All around her screaming such as she had never before heard grew louder. What must one do to a man to make him scream so?

Fear. Overpowering, paralysing, choking fear.

Again the clash of iron, the grunts and snorts of the horses. The houses whirled around her and suddenly she could see windows belching fire where a moment before there’d been nothing but a muddy little street strewn with corpses and cluttered with the abandoned possessions of the fleeing population. All at once the knight at her back was racked by a strange wheezing cough. Blood spurted over the hands grasping the reins. More screams. Arrows whistled past.

A fall, a shock, painful bruising against armour. Hooves pounded past her, a horse’s belly and a frayed girth flashing by above her head, then another horse’s belly and a flowing black caparison. Grunts of exertion, like a lumberjack’s when chopping wood. But this isn’t wood; it’s iron against iron. A shout, muffled and dull, and something huge and black collapsed into the mud next to her with a splash, spurting blood. An armoured foot quivered, thrashed, goring the earth with an enormous spur.

A jerk. Some force plucked her up, pulled her onto another saddle. Hold on! Again the bone-shaking speed, the mad gallop. Arms and legs desperately searching for support. The horse rears. Hold on! … There is no support. There is no … There is no … There is blood. The horse falls. It’s impossible to jump aside, no way to break free, to escape the tight embrace of these chainmail-clad arms. There is no way to avoid the blood pouring onto her head and over her shoulders.

A jolt, the squelch of mud, a violent collision with the ground, horrifically still after the furious ride. The horse’s harrowing wheezes and squeals as it tries to regain its feet. The pounding of horseshoes, fetlocks and hooves flashing past. Black caparisons and cloaks. Shouting.

The street is on fire, a roaring red wall of flame. Silhouetted before it, a rider towers over the flaming roofs, enormous. His black-caparisoned horse prances, tosses its head, neighs.

The rider stares down at her. Ciri sees his eyes gleaming through the slit in his huge helmet, framed by a bird of prey’s wings. She sees the fire reflected in the broad blade of the sword held in his lowered hand.

The rider looks at her. Ciri is unable to move. The dead man’s motionless arms wrapped around her waist hold her down. She is locked in place by something heavy and wet with blood, something which is lying across her thigh, pinning her to the ground.

And she is frozen in fear: a terrible fear which turns her entrails inside out, which deafens Ciri to the screams of the wounded horse, the roar of the blaze, the cries of dying people and the pounding drums. The only thing which exists, which counts, which still has any meaning, is fear. Fear embodied in the figure of a black knight wearing a helmet decorated with feathers frozen against the wall of raging, red flames.

The rider spurs his horse, the wings on his helmet fluttering as the bird of prey takes to flight, launching itself to attack its helpless victim, paralysed with fear. The bird—or maybe the knight—screeches terrifyingly, cruelly, triumphantly. A black horse, black armour, a black flowing cloak, and behind this—flames. A sea of flames.

Fear.

The bird shrieks. The wings beat, feathers slap against her face. Fear!

Help! Why doesn’t anyone help me? Alone, weak, helpless—I can’t move, can’t force a sound from my constricted throat. Why does no one come to help me?

I’m terrified!

Eyes blaze through the slit in the huge winged helmet. The black cloak veils everything—

“Ciri!”

She woke, numb and drenched in sweat, with her scream—the scream which had woken her—still hanging in the air, still vibrating somewhere within her, beneath her breastbone and burning against her parched throat. Her hands ached, clenched around the blanket; her back ached …

“Ciri. Calm down.”

The night was dark and windy, the crowns of the surrounding pine trees rustling steadily and melodiously, their limbs and trunks creaking in the wind. There was no malevolent fire, no screams, only this gentle lullaby. Beside her the campfire flickered with light and warmth, its reflected flames glowing from harness buckles, gleaming red in the leather-wrapped and iron-banded hilt of a sword leaning against a saddle on the ground. There was no other fire and no other iron. The hand against her cheek smelled of leather and ashes. Not of blood.

“Geralt—”

“It was just a dream. A bad dream.”

Ciri shuddered violently, curling her arms and legs up tight.

A dream. Just a dream.

The campfire had already died down; the birch logs were red and luminous, occasionally crackling, giving off tiny spurts of blue flame which illuminated the white hair and sharp profile of the man wrapping a blanket and sheepskin around her.

“Geralt, I—”

“I’m right here. Sleep, Ciri. You have to rest. We’ve still a long way ahead of us.”

I can hear music, she thought suddenly. Amidst the rustling of the trees … there’s music. Lute music. And voices. The Princess of Cintra … A child of destiny … A child of Elder Blood, the blood of elves. Geralt of Rivia, the White Wolf, and his destiny. No, no, that’s a legend. A poet’s invention. The princess is dead. She was killed in the town streets while trying to escape …

Hold on …! Hold …

“Geralt?”

“What, Ciri?”

“What did he do to me? What happened? What did he … do to me?”

“Who?”

“The knight … The black knight with feathers on his helmet … I can’t remember anything. He shouted … and looked at me. I can’t remember what happened. Only that I was frightened … I was so frightened …”

The man leaned over her, the flame of the campfire sparkling in his eyes. They were strange eyes. Very strange. Ciri had been frightened of them; she hadn’t liked meeting his gaze. But that had been a long time ago. A very long time ago.

“I can’t remember anything,” she whispered, searching for his hand, as tough and coarse as raw wood. “The black knight—”

“It was a dream. Sleep peacefully. It won’t come back.”

Ciri had heard such reassurances in the past. They had been repeated to her endlessly; many, many times she had been offered comforting words when her screams had woken her during the night. But this time it was different. Now she believed it. Because it was Geralt of Rivia, the White Wolf, the Witcher, who said it. The man who was her destiny. The one for whom she was destined. Geralt the Witcher, who had found her surrounded by war, death and despair, who had taken her with him and promised they would never part.

She fell asleep holding tight to his hand.

The bard finished the song. Tilting his head a little he repeated the ballad’s refrain on his lute, delicately, softly, a single tone higher than the apprentice accompanying him.

No one said a word. Nothing but the subsiding music and the whispering leaves and squeaking boughs of the enormous oak could be heard. Then, all of a sudden, a goat tethered to one of the carts which circled the ancient tree bleated lengthily. At that moment, as if given a signal, one of the men seated in the large semi-circular audience stood up. Throwing his cobalt blue cloak with gold braid trim back over his shoulder, he gave a stiff, dignified bow.

“Thank you, Master Dandelion,” he said, his voice resonant without being loud. “Allow me, Radcliffe of Oxenfurt, Master of the Arcana, to express what I am sure is the opinion of everyone here present and utter words of gratitude and appreciation for your fine art and skill.”

The wizard ran his gaze over those assembled—an audience of well over a hundred people—seated on the ground, on carts, or standing in a tight semi-circle facing the foot of the oak. They nodded and whispered amongst themselves. Several people began to applaud while others greeted the singer with upraised hands. Women, touched by the music, sniffed and wiped their eyes on whatever came to hand, which differed according to their standing, profession and wealth: peasant women used their forearms or the backs of their hands, merchants’ wives dabbed their eyes with linen handkerchiefs while elves and noblewomen used kerchiefs of the finest tight-woven cotton, and Baron Vilibert’s three daughters, who had, along with the rest of his retinue, halted their falcon hunt to attend the famous troubadour’s performance, blew their noses loudly and sonorously into elegant mould-green cashmere scarves.

“It would not be an exaggeration to say,” continued the wizard, “that you have moved us deeply, Master Dandelion. You have prompted us to reflection and thought; you have stirred our hearts. Allow me to express our gratitude, and our respect.”

The troubadour stood and took a bow, sweeping the heron feather pinned to his fashionable hat across his knees. His apprentice broke off his playing, grinned and bowed too, until Dandelion glared at him sternly and snapped something under his breath. The boy lowered his head and returned to softly strumming his lute strings.

The assembly stirred to life. The merchants travelling in the caravan whispered amongst themselves and then rolled a sizable cask of beer out to the foot of the oak tree. Wizard Radcliffe lost himself in quiet conversation with Baron Vilibert. Having blown their noses, the baron’s daughters gazed at Dandelion in adoration—which went entirely unnoticed by the bard, engrossed as he was in smiling, winking and flashing his teeth at a haughty, silent group of roving elves, and at one of them in particular: a dark-haired, large-eyed beauty sporting a tiny ermine cap. Dandelion had rivals for her attention—the elf, with her huge eyes and beautiful toque hat, had caught his audience’s interest as well, and a number of knights, students and goliards were paying court to her with their eyes. The elf clearly enjoyed the attention, picking at the lace cuffs of her chemise and fluttering her eyelashes, but the group of elves with her surrounded her on all sides, not bothering to hide their antipathy towards her admirers.

The glade beneath Bleobheris, the great oak, was a place of frequent rallies, a well-known travellers’ resting place and meeting ground for wanderers, and was famous for its tolerance and openness. The druids protecting the ancient tree called it the Seat of Friendship and willingly welcomed all comers. But even during an event as exceptional as the world-famous troubadour’s just-concluded performance the travellers kept to themselves, remaining in clearly delineated groups. Elves stayed with elves. Dwarfish craftsmen gathered with their kin, who were often hired to protect the merchant caravans and were armed to the teeth. Their groups tolerated at best the gnome miners and halfling farmers who camped beside them. All non-humans were uniformly distant towards humans. The humans repaid in kind, but were not seen to mix amongst themselves either. Nobility looked down on the merchants and travelling salesmen with open scorn, while soldiers and mercenaries distanced themselves from shepherds and their reeking sheepskins. The few wizards and their disciples kept themselves entirely apart from the others, and bestowed their arrogance on everyone in equal parts. A tight-knit, dark and silent group of peasants lurked in the background. Resembling a forest with their rakes, pitchforks and flails poking above their heads, they were ignored by all and sundry.

The exception, as ever, was the children. Freed from the constraints of silence which had been enforced during the bard’s performance, the children dashed into the woods with wild cries, and enthusiastically immersed themselves in a game whose rules were incomprehensible to all those who had bidden farewell to the happy years of childhood. Children of elves, dwarves, halflings, gnomes, half-elves, quarter-elves and toddlers of mysterious provenance neither knew nor recognised racial or social divisions. At least, not yet.

“Indeed!” shouted one of the knights present in the glade, who was as thin as a beanpole and wearing a red and black tunic emblazoned with three lions passant. “The wizard speaks the truth! The ballads were beautiful. Upon my word, honourable Dandelion, if you ever pass near Baldhorn, my lord’s castle, stop by without a moment’s hesitation. You will be welcomed like a prince—What am I saying? Welcomed like King Vizimir himself! I swear on my sword, I have heard many a minstrel, but none even came close to being your equal, master. Accept th

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...